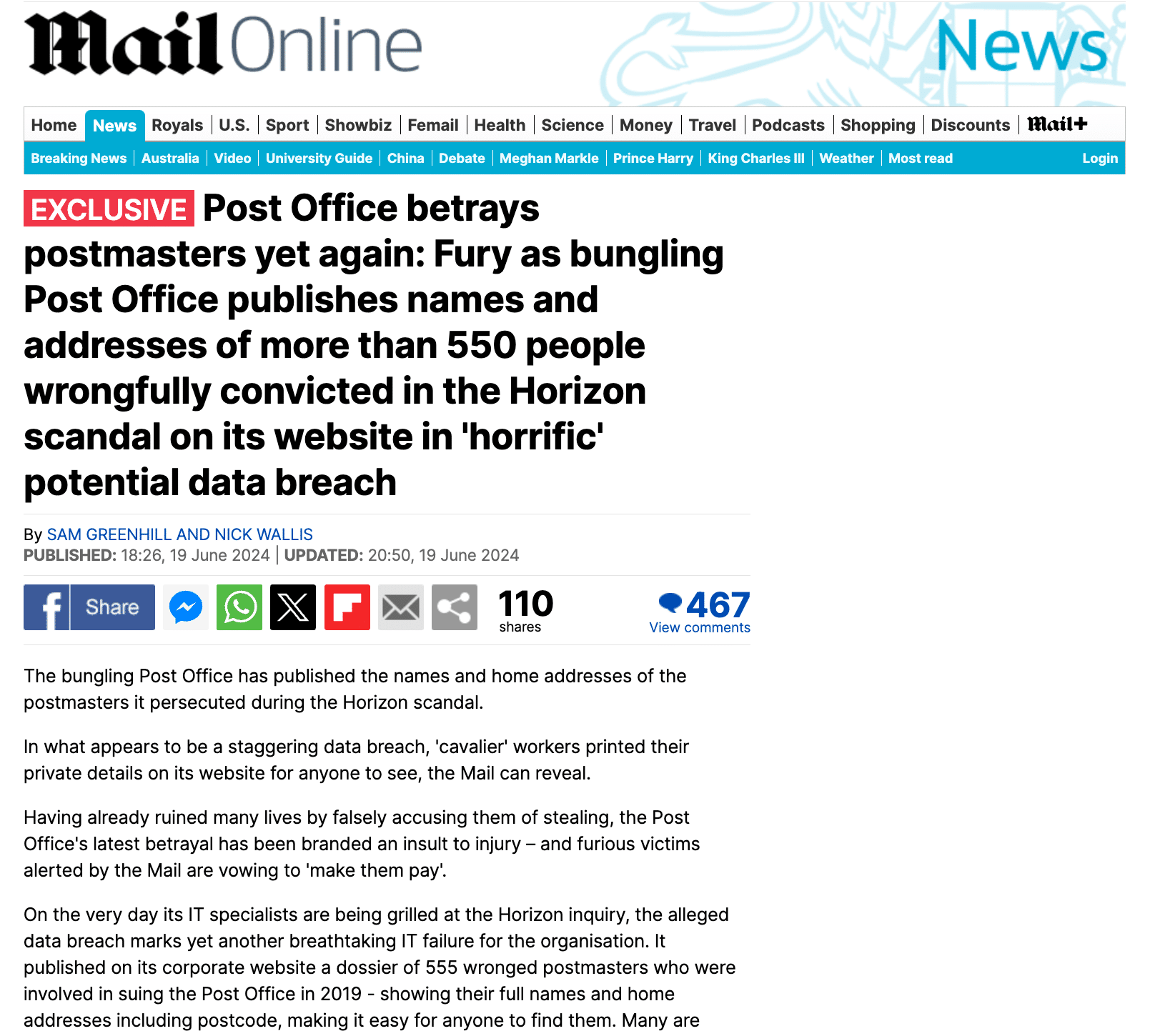

We wrote last month about Paul Baxendale-Walker, the former barrister and solicitor who helped create the “loan schemes” that cost the country £billions and caused misery for tens of thousands of people. HMRC say his schemes avoided £1bn in tax. His advice was negligent, and he eventually ended up struck off, bankrupt, and convicted of forgery. But HMRC made a series of errors, including missing a statutory deadline, which let Baxendale-Walker escape a £14m penalty.

We can now reveal that, at about the same time, HMRC issued a statutory “stop notice” to stop Baxendale-Walker’s latest “Nova Trust” scheme being promoted… but HMRC mistakenly issued it to a company that had been struck-off.

The Nova Trust scheme continued to be promoted after the stop notice. This would normally mean HMRC could apply penalties or even criminal sanctions – but, thanks to HMRC’s mistake, it’s likely there’s now nothing HMRC can do.

And HMRC seem to be making a habit of procedural errors in avoidance cases. Just last week, a major case was struck out because HMRC missed a 5pm deadline for filing a bundle of supporting authorities.1 And there was a similar case last year, where HMRC’s failure to meet deadlines led to it being permanently barred from a £7m VAT case.

Baxendale-Walker – the Nova trust

The background to Baxendale-Walker and HMRC’s efforts to pursue him is set out in our previous report. The summary in the introductory paragraph above gives just a small flavour of why investigating him should be an HMRC priority.

Baxendale-Walker says he retired in 2013 on grounds of ill-health.2 However businesses linked to Baxendale-Walker have continued to be actively involved in extensive litigation in the US and UK3. And they continue to sell tax schemes, largely based around solving problems created by their previous tax schemes.

In May 2023, HMRC published details of two schemes promoted by two Belize companies linked to Baxendale-Walker, Buckingham Wealth Ltd and Minerva Services Ltd.4. The companies appear to have no internet presence; the various other Buckingham Wealth companies found by a Google search have no connection to Baxendale-Walker.

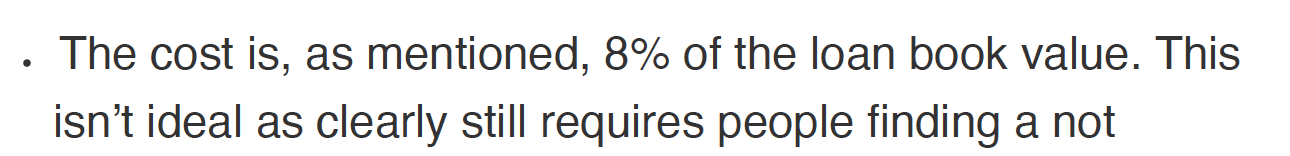

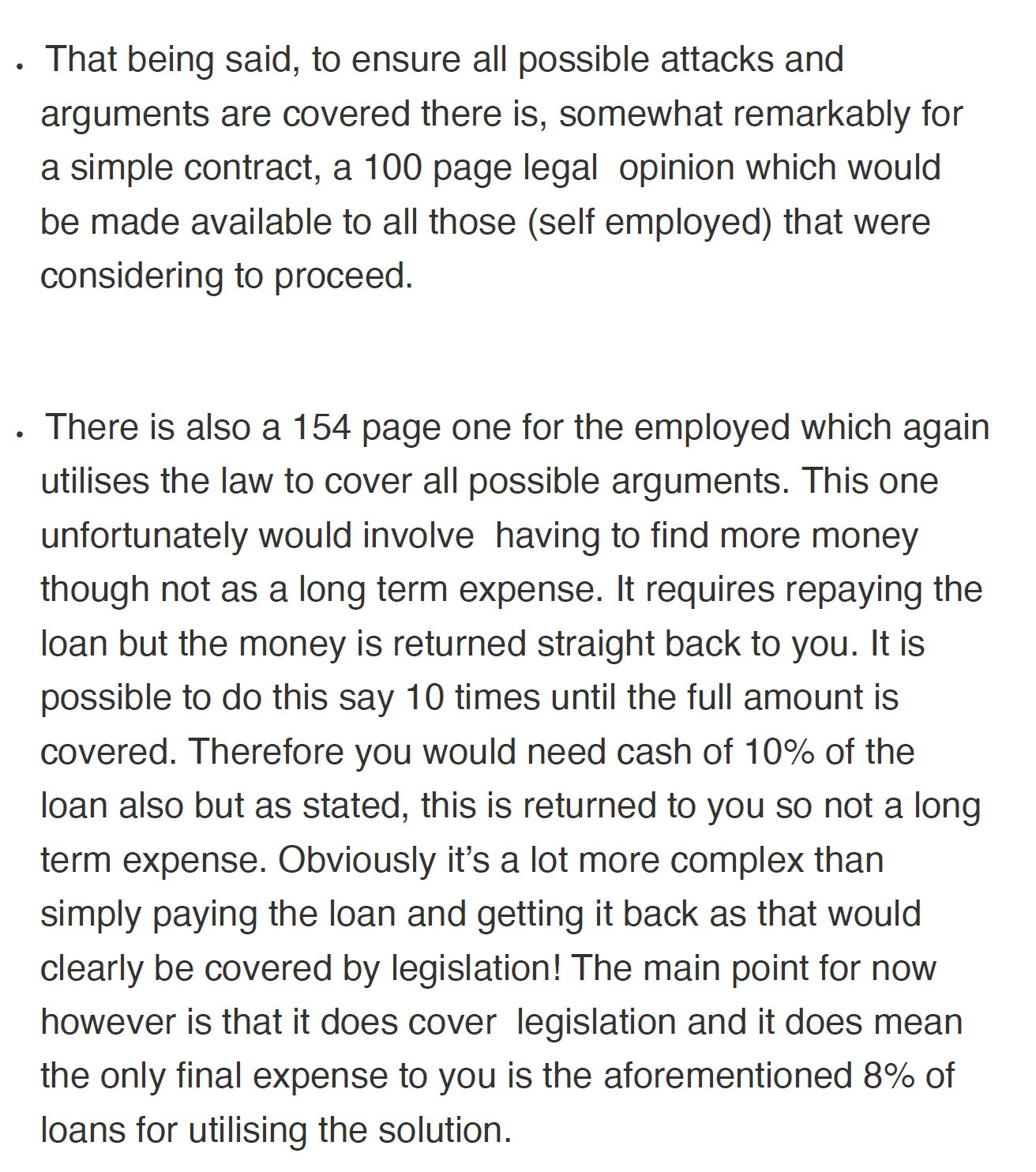

The first scheme is a “umbrella remuneration trust” which supposedly lets you take what should be taxable earnings as a non-taxable loan. It’s either the same or a variant of the scheme that two dentists bought in 2014,5 and Baxendale-Walker was reported to be selling in 2016.

The second scheme is a bizarre attempt to prevent HMRC enquiring into the first scheme, by claiming the “umbrella remuneration trust” was void6, and making a “replacement” contribution to a new trust called the “Nova” trust. This is not the first time a Baxendale-Walker scheme has attempted to “rebrand” a previous failed scheme – a court recently found a previous attempt to do so to be dishonest.7 Arguments of this kind are the subject of a number of current tax appeals, and they are (predictably) not going well.

On 3 May 2023, HMRC took the unusual step of publishing Buckingham Wealth Ltd‘s marketing material for the “Nova” trust:

HMRC went further, and alleged that Buckingham Wealth Ltd did not appear to believe that one of its own tax avoidance schemes works. If correct, that could amount to (criminal) tax fraud (although as far as we are aware no charge have been brought).

Paul Baxendale-Walker is not mentioned in the document, and HMRC’s PDF contains no metadata. We have, however, obtained8 an original PDF containing a slightly later version of the FAQ.9

Metadata in this PDF shows that “Paul” created the document on 14 June 2022 using Microsoft Word.10 We have spoken to three people familiar with Baxendale-Walker’s writing style; they each independently, without prompting, identified him as the likely author.

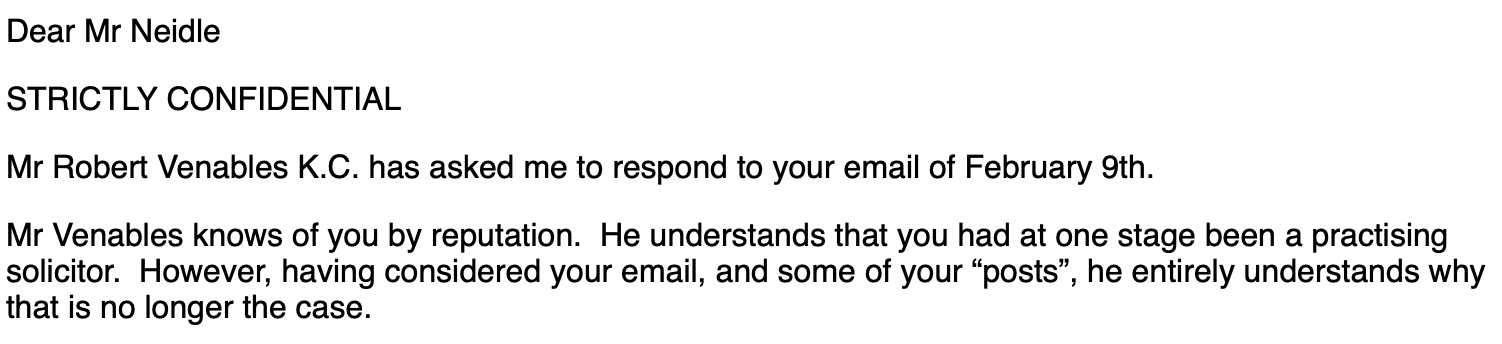

When we initially asked Baxendale-Walker about Nova, he said there was no such thing as a “Nova” trust. When we subsequently put the evidence of authorship to him he said that the document “was the product of collegiate discussion”.

HMRC’s response – the stop notice

In July 2023, two months after publishing the Nova Trust materials, HMRC issued a “stop notice” to Buckingham Wealth Ltd.

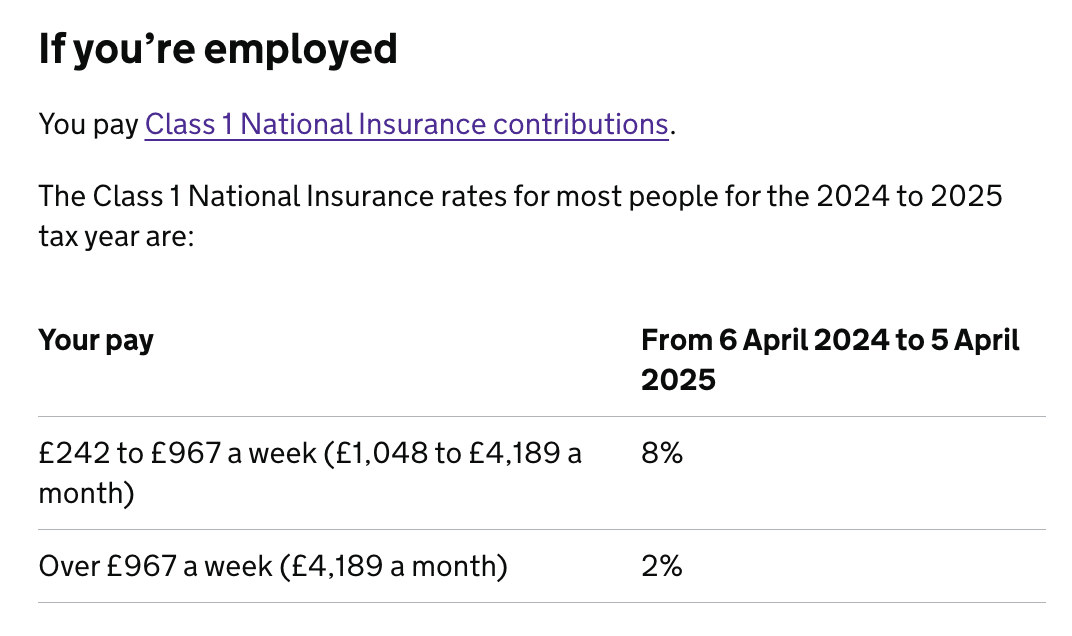

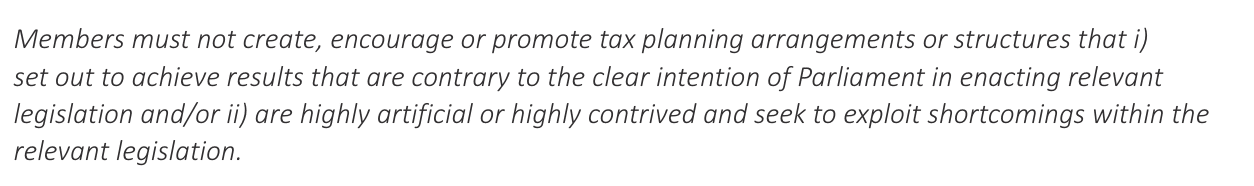

“Stop notices” were a new power granted to HMRC in 2021, with the rules now in section 236A Finance Act 2014.

The effect of a stop notice is that the recipient of the stop notice mustn’t promote the specified arrangements, or anything similar to them. This restriction also applies to (amongst others) anyone who controls, or has significant influence, over the recipient of the stop notice. And if the recipient transfers its business to another person, then the stop notice applies to them too.

The stop notice also requires the recipient to provide HMRC with detailed information on its clients, and to pass details of the stop notice to those clients.

HMRC’s mistake

HMRC’s stop notice was issued to Buckingham Wealth Ltd in July 2023.

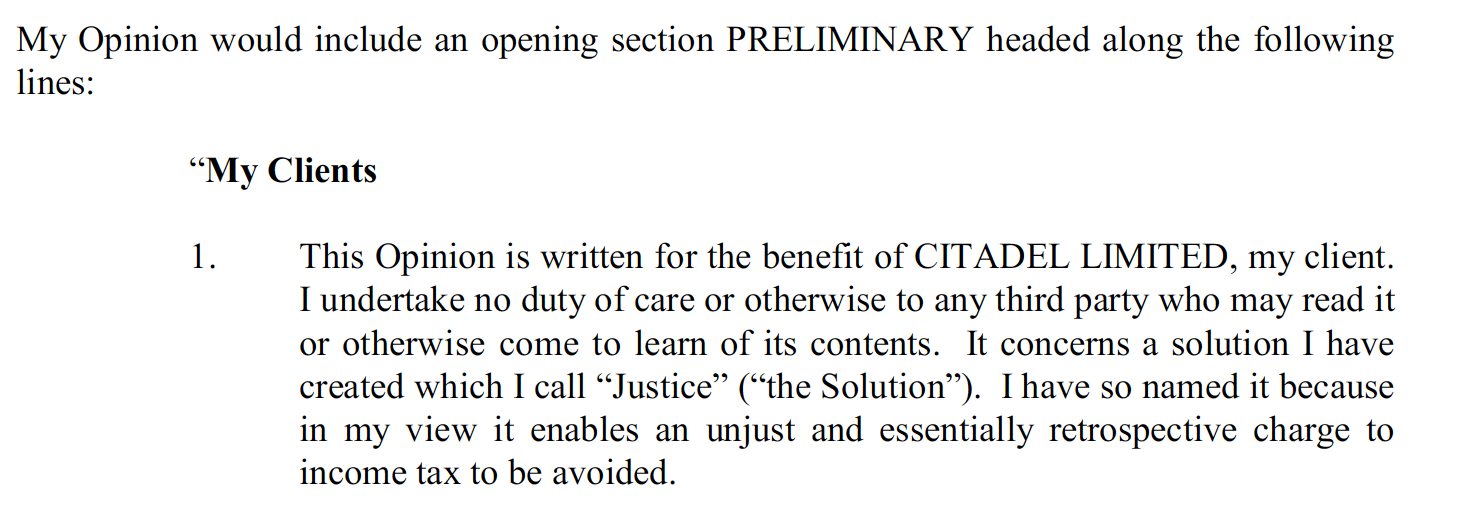

This looks like a bad mistake, because Buckingham Wealth Ltd was struck off the Belize register of companies six months earlier:

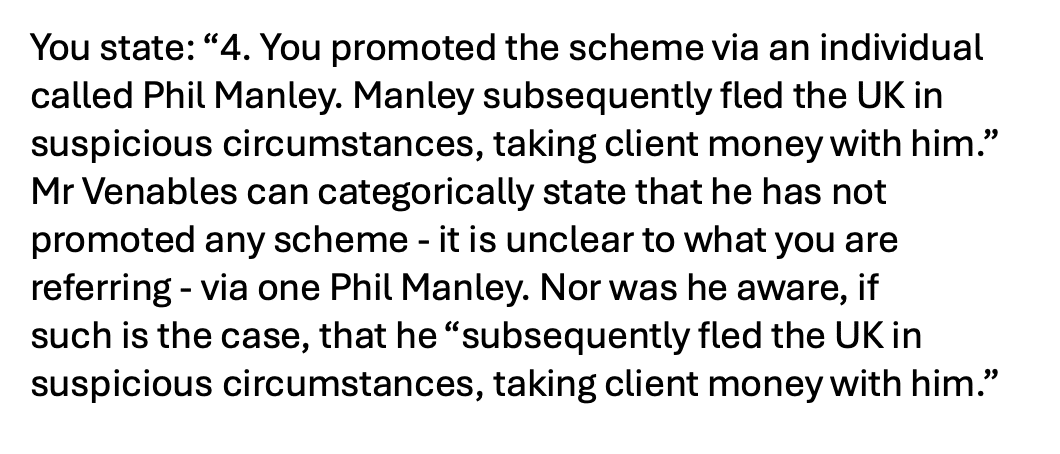

Baxendale-Walker told us that his lawyers had assured him Buckingham Wealth Ltd “ceased to have legal existence”, and this makes HMRC’s stop notice invalid.

We asked HMRC for their response:

We’ve spoken to Belize counsel, and it’s our view that whether the company existed at the time is not the correct question.

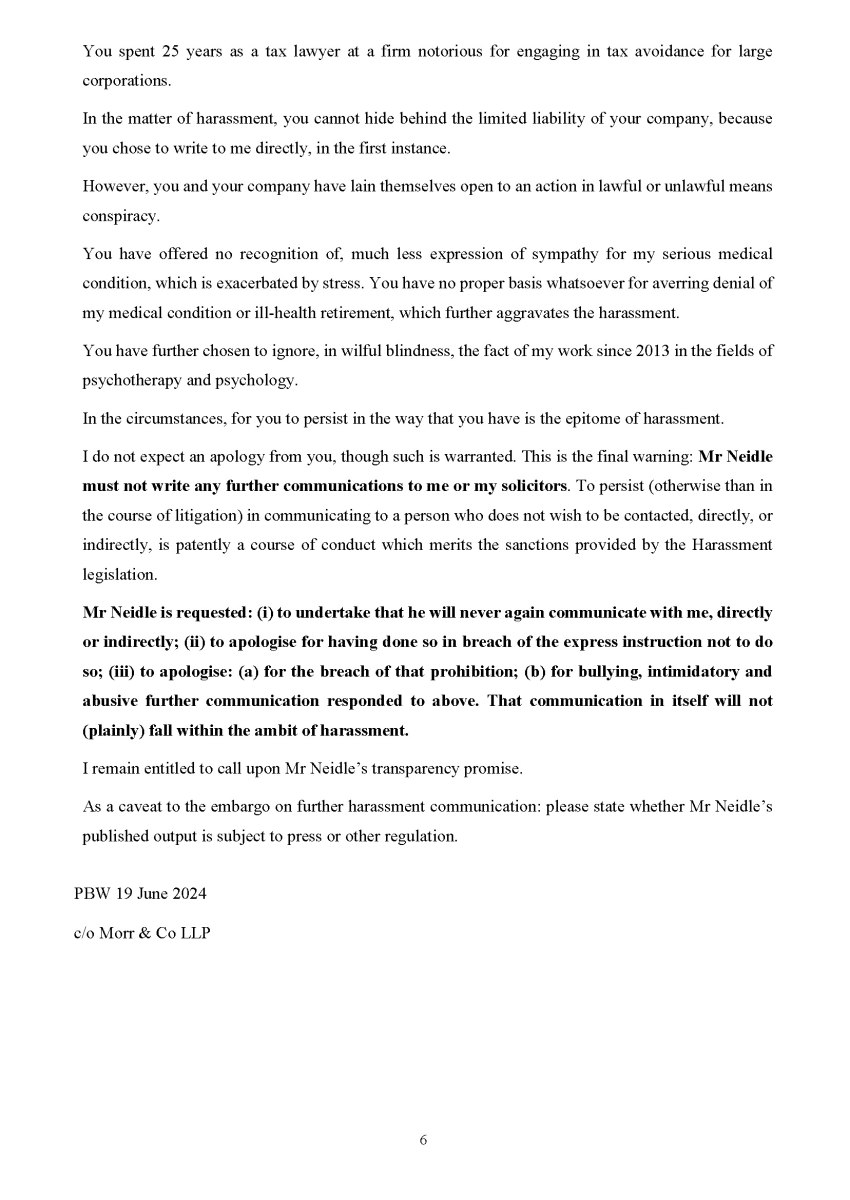

The Belize Companies Act 2022 makes a clear distinction between a company that is dissolved and a company that is struck off. A dissolved company ceases to exist. A struck-off company which has not yet been dissolved exists in a kind of “zombie” state, where it can’t engage in activity, but remains liable for its debts and can be pursued by creditors (see section 220).

So the question isn’t whether Buckingham Wealth Ltd existed and the stop notice was valid – technically it’s reasonably clear that the company did exist. But the fact the Buckingham Wealth Ltd was struck off means that the stop notice was useless. Buckingham Wealth Ltd was not going to engage in promotional activities itself, had (we expect) already transferred its business to another person, and nobody11 had control or influence over it anymore. So the stop notice likely had no practical effect.

This was, therefore, a bad mistake by HMRC. It’s usually standard procedure for lawyers commencing any kind of transaction or procedure involving a company to, on the morning of the day in question, check if the company remains in existence. If we could check the Belize incorporation status of Buckingham Wealth Ltd, HMRC certainly could. Upon discovering the company had been struck-off, HMRC should have either issued the stop notice to another entity (such as Minerva Services Ltd)12 or to identifiable humans involved in these companies (such as Paul Baxendale-Walker himself, Saeedeh Mirshahi, or other of his associates).

HMRC doesn’t appear to have done this.

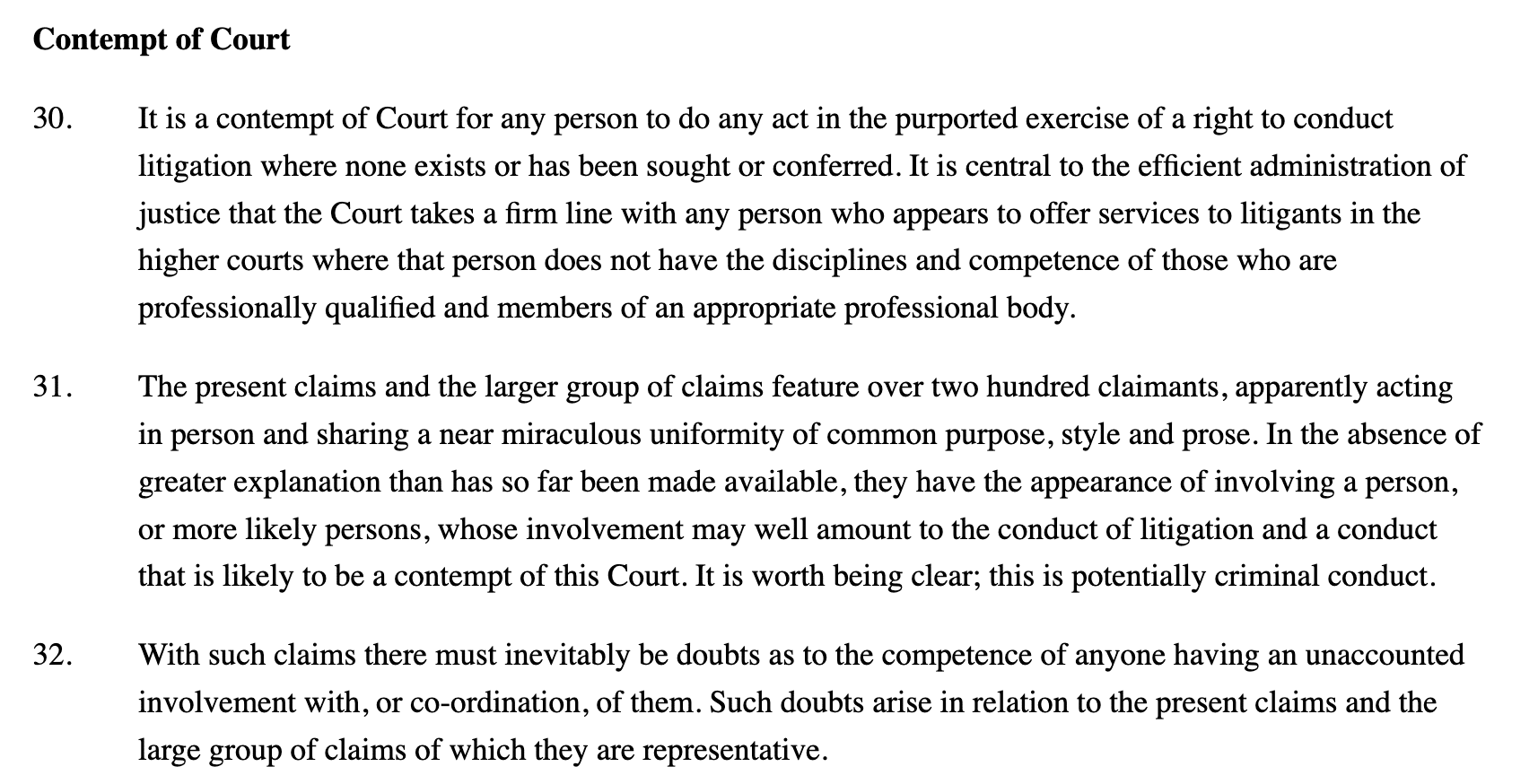

The consequence of HMRC’s mistake

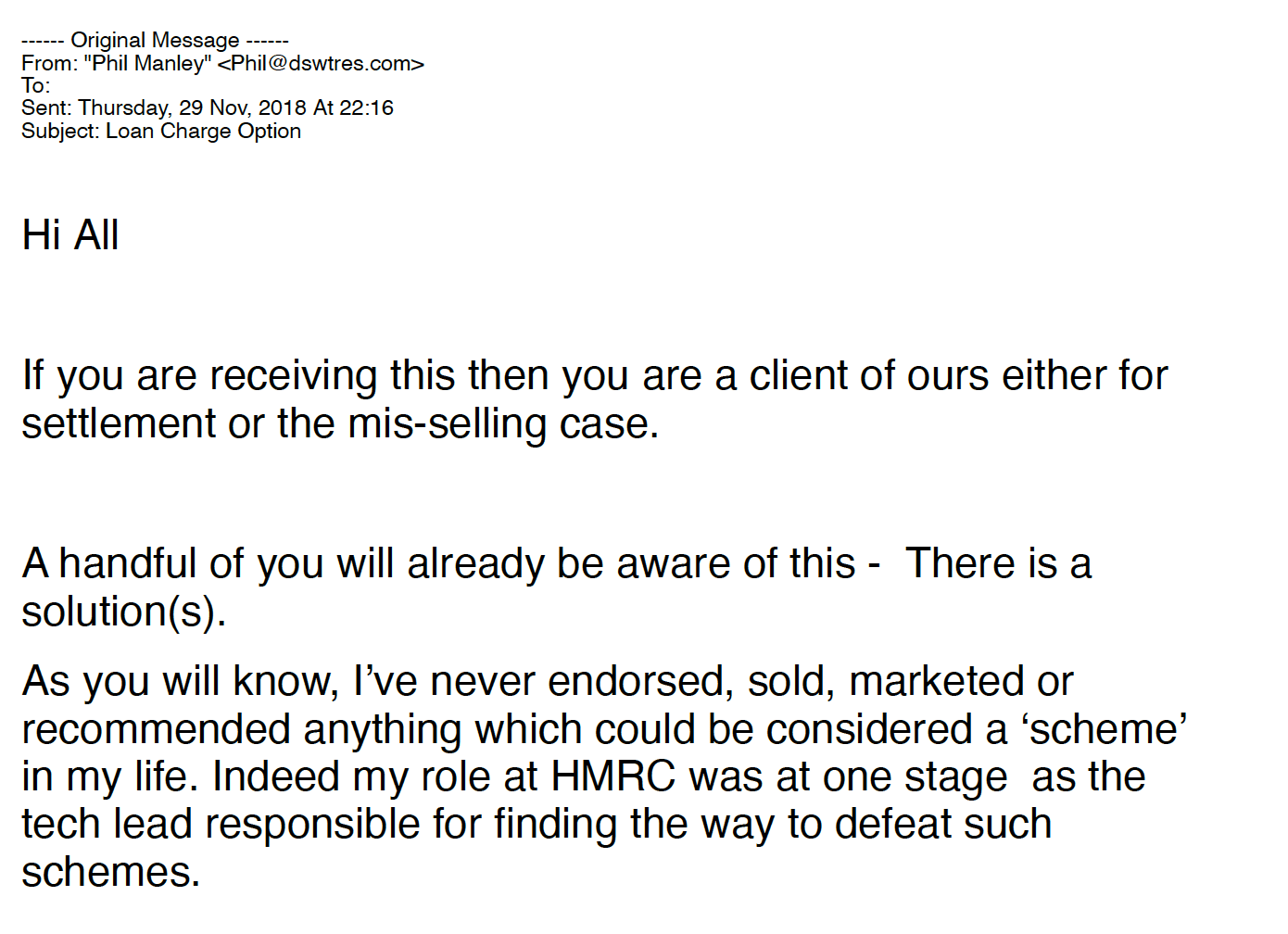

It appears that Buckingham Wealth kept promoting the Nova trust, and ran a conference at Heathrow in January 2024.

This wasn’t “Buckingham Wealth Ltd”, which no longer existed. It was either another company called “Buckingham Wealth” hiding its name and place of incorporation, or a group of individuals acting under the “Buckingham Wealth” brand. This is not how people ordinarily run a business, and we’d speculate that the purpose was to make HMRC’s job harder.

Here’s an email summarising the conference from Osmai Management, a very dubious-looking BVI firm13 that appears to act as an “introducer” selling Buckingham Wealth’s schemes (PDF here):14

Baxendale-Walker did not deny that the Heathrow event happened. He said it didn’t involve Buckingham Wealth Ltd, because the company no longer existed. He said that he was aware that various persons refer to various tax arrangements under the umbrella “Buckingham Wealth”, and that is “merely a name or style”. He added, oddly answering a question we hadn’t answered, that he had “no knowledge who the natural persons are who own ‘Osmai’”.

We do not know for certain, on the basis of the information we currently possess, whether Baxendale-Walker was involved in the Heathrow event. However we infer from the non-denial, from Baxendale-Walker’s history, and from the very Baxendale-Walker-sounding summary of the Heathrow event in the Osmai email, that he may have been involved in it.

At this point, HMRC would ordinarily want to apply penalties for breaching the stop notice. This could be on the basis that the business of Buckingham Wealth Ltd had been transferred to a new person or persons, in which case the stop notice would now bind them. Or it could be on the basis that the people running the event (Baxendale-Walker or others) previously had influence/control over Buckingham Wealth Ltd, in which case the stop notice would bind them personally.

And if marketing continued past Finance Act 2024 coming into force on 22 February 2024, then HMRC would want to apply the new legislation that makes any breach of a stop notice a criminal offence.

However, HMRC are in our view unable to do any of these things, because they issued the stop notice to a struck-off company. The stop notice should have been issued to Baxendale-Walker personally.

What can HMRC do now?

We do not know if HMRC was aware of the problem with the stop notice before we contacted them. We also don’t know if HMRC was aware of the Heathrow event before this article. But we are concerned that HMRC’s investigation of Baxendale-Walker has been both extremely long-running and remarkably unsuccessful.

HMRC should investigate the Heathrow event and the background to Buckingham Wealth Ltd in more detail. It may be that we are wrong and there are facts and circumstances that mean the stop notice was breached. Certainly that should be checked.

And HMRC should share its information with the Official Receiver to see if any bankruptcy offences have been committed.15

Baxendale-Walker is subject to extended bankruptcy restrictions until 2030. This means that it’s an offence for him to act as director of a company or directly or indirectly to take part in or be concerned in the promotion, formation or management of a company, without the leave of the court.

If Baxendale-Walker was involved in the management of Buckingham Wealth Ltd, Minerva Services Ltd, or any other entity, that would appear to be an offence.

Was he?

There was more than a suggestion in a High Court judgment last year that Baxendale-Walker was managing a Delaware company.16 Similar allegations were made by a party to another case this year.

Baxendale-Walker firmly denied to us he was breaching the bankruptcy restrictions, and added that it would be a libel to say that he was. However, given the various allegations made in recent cases, the wave of litigation launched by associated entities, Baxendale-Walker’s history of using opaquely owned companies to pursue his own agendas, conviction for fraud, use of trusts to hide ownership, and his failure to make full and frank disclosure of his affairs to the Official Receiver, we would suggest there are good grounds for an investigation into his precise relationship with the large number of companies that appear to be associated with him.

Many thanks to M for his research and analysis on Buckingham Wealth, I for the Belize advice, and K for general research.

Photo by Paul Baxendale-Walker – CC BY 3.0, edited for resolution and aspect ratio by Tax Policy Associates Ltd

Footnotes

Ordinarily, missing a deadline doesn’t have this effect. The judge had made an “unless” order, which means that failure to adhere to his directions results in the case being struck out – we expect this was because HMRC had missed a series of previous deadlines. HMRC can apply for the case to be reinstated; this is often granted where there has been a one-off administrative mistake, but (as in last year’s ebuyer case) is not always granted where there has been a pattern of failures to meet tribunal deadlines ↩︎

His Facebook page describes him as “Songwriter & Guitarist, Scriptwriter, Actor, Director, Producer” ↩︎

In addition to the Delaware arbitration that led to that Court of Appeal decision, PBW has continued to file claims in his own name. In addition, a series of companies that appear to be related to PBW seem to be engaged in ongoing litigation, much of which relates around purported assignments to new entities. Given PBW’s track record, and the number of times he has been severely criticised by judges in the UK and US, it is unclear why the various defendants to his claims haven’t applied for a civil restraint order. ↩︎

There is no way of ascertaining the beneficial owner of Belize companies; we infer from facts in reported cases that PBW is likely associated with Minerva (see for example this footnote to our original report). Previously the Minerva business was carried out by a BVI company of the same name; an unsuccessful court application which bears the hallmarks of PBW attempted to transfer its assets to the Belize company. There is less information publicly available regarding Buckingham Wealth; but it appears to have been the promoter in the Hosking case, and the Ashbolt case described “Buckingham Wealth LLP” as the successor to Baxendale Walker LLP. We don’t know if these are different entities, perhaps another move from the BVI to Belize, one entity which changed form, or if the differences just reflect errors. ↩︎

which may or may not be the same scheme another dentist bought five years earlier, and appears similar to the “Sunrise” scheme at issue in the Hosking and Horsler cases. ↩︎

It’s pretty clear this doesn’t work, both on general principles and from the Hosking case ↩︎

Baxendale-Walker and his entities were not a party in that case and, as far as we know, HMRC has no accused Baxendale-Walker or his entities of behaving dishonestly. ↩︎

From someone who received a copy of the document from an introducer ↩︎

With minor textual differences, corrections of grammatical errors/partial sentences, and the addition of the ability to spread the fee out over time. ↩︎

It of course being noted that this does not prove Paul Baxendale-Walker wrote the document; it could be another “Paul”, or indeed anyone who setup Word with “Paul” as the author. ↩︎

Because it was probably held by a trust of some kind, rather than by Baxendale-Walker or another traceable individual directly. ↩︎

which was struck off in January 2024 ↩︎

Despite being incorporated in the BVI, Osmai’s website provides only a UK telephone number and its website lists only UK taxes. Until January 2019 they promoted Baxendale-Walker’s “umbrella remuneration trust”, with the claim that it was fully disclosed to HMRC and wasn’t tax avoidance. HMRC predictably did not agree. Another Osmai entity, which gives the same UK phone number, appears to operate an unauthorised FX trading scheme which makes some very suspicious claims and may be fraudulent. We attempted to contact Osmai Management for comment and received no response. ↩︎

It’s redacted to protect our source, and we have masked the precise date for the same reason ↩︎

HMRC usually is heavily constrained by taxpayer confidentiality, but it is usually able to disclose information to the Official Receiver. ↩︎

“In these proceedings, it is said that MSD [Minerva Services Delaware, Inc.] is a shadowy company, which seeks to rely on documents which appear uncommercial and which call out for an explanation, at the very least. It is also wholly unclear who is standing behind MSD. Mr Patel also says that it is obviously Mr Baxendale-Walker and he raises more than a prima facie case that this is indeed so. Indeed, Counsel for MSD accepted for the purposes of the strike out/summary judgment that the Court had to assume that this was indeed so. I note that Mr Baxendale-Walker was made bankrupt in 2018, after a former client sued him for negligence and obtained a judgment of over £16 million against him.” ↩︎

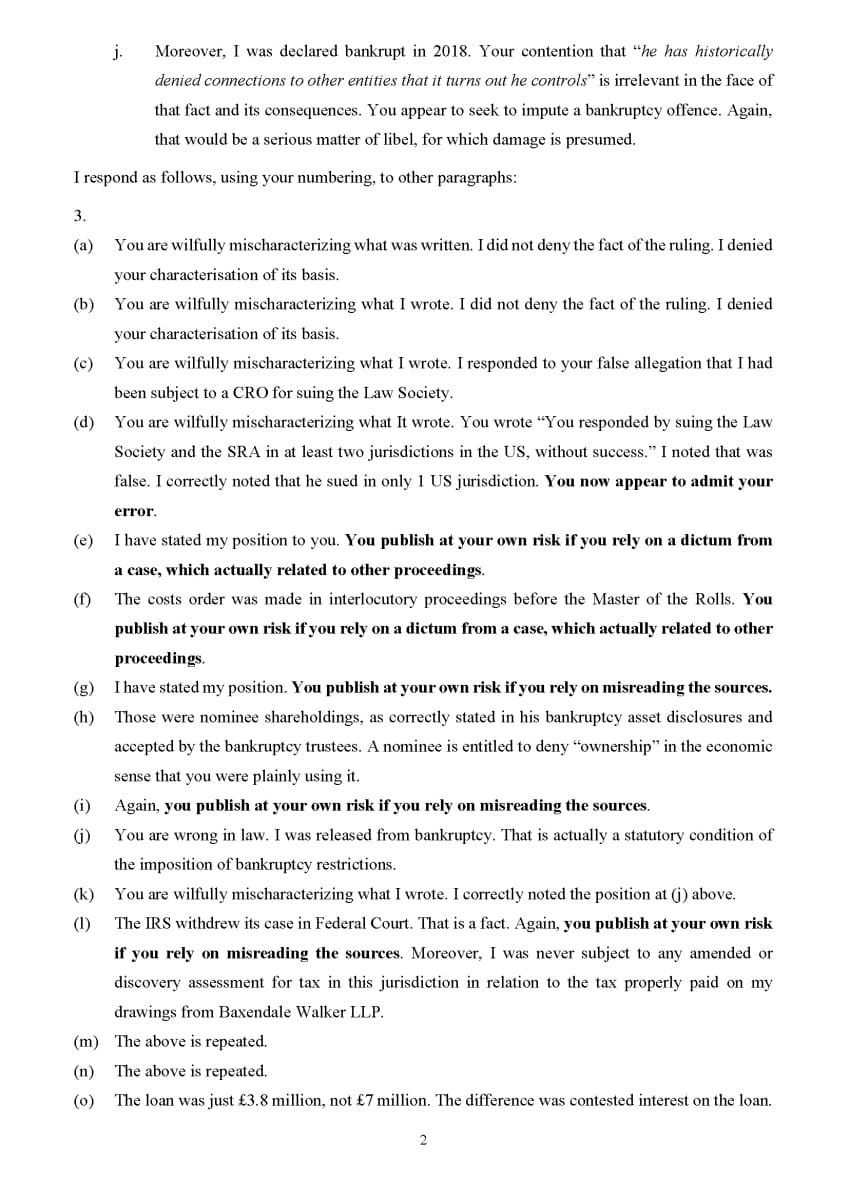

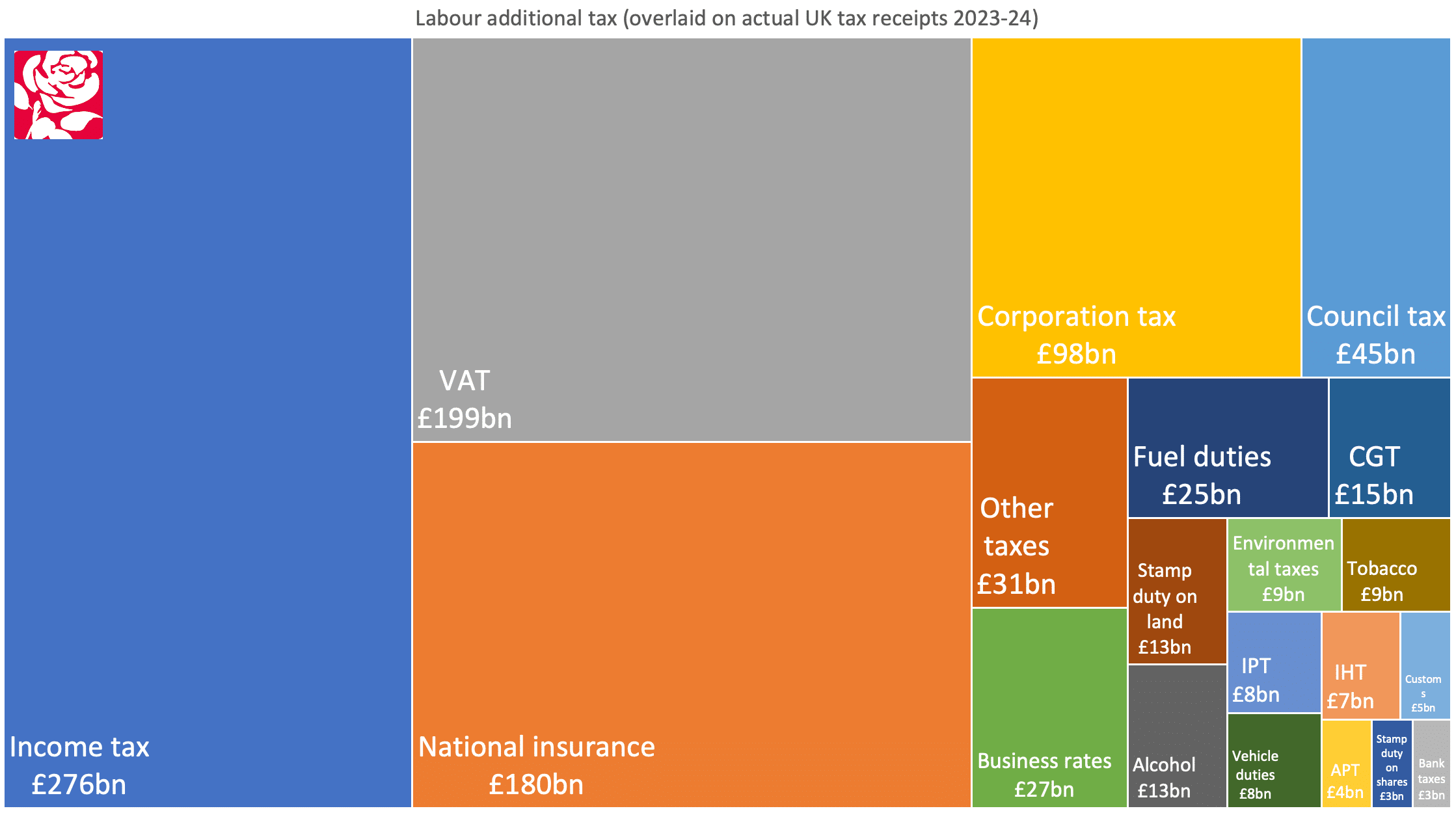

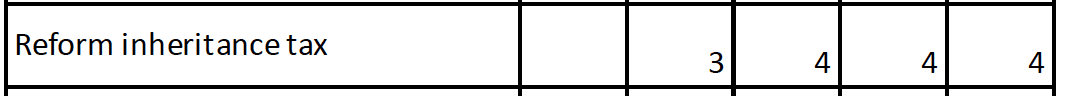

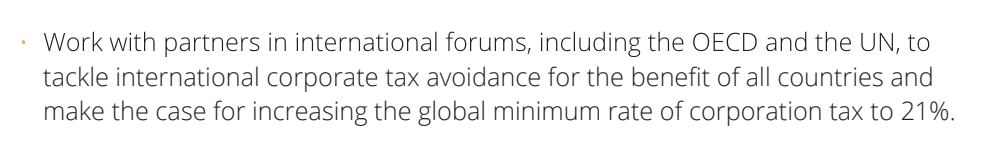

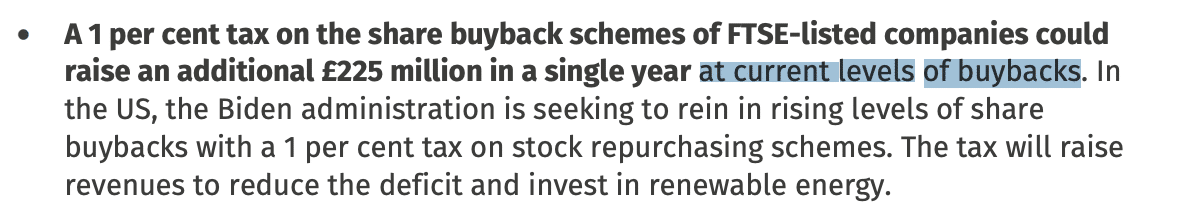

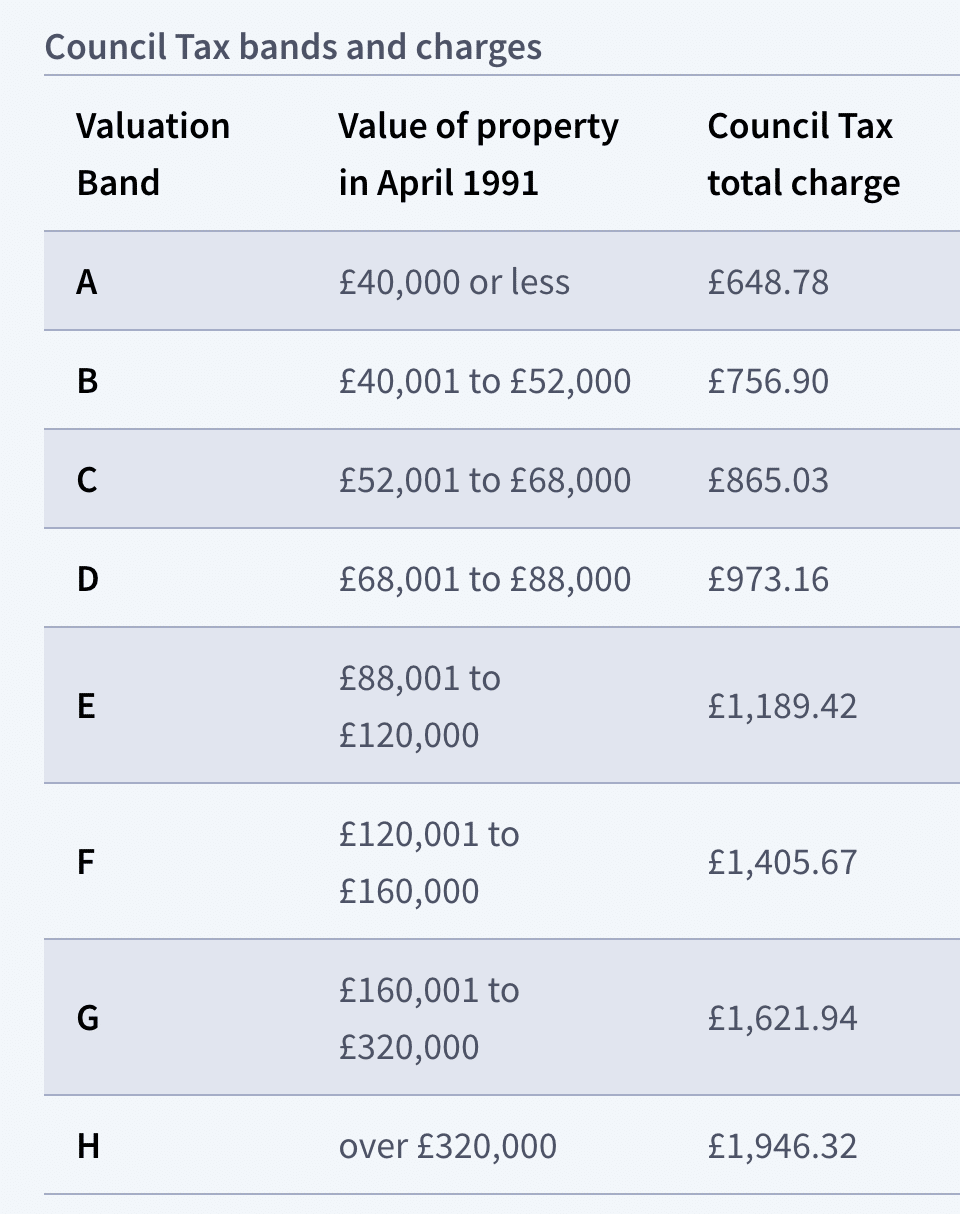

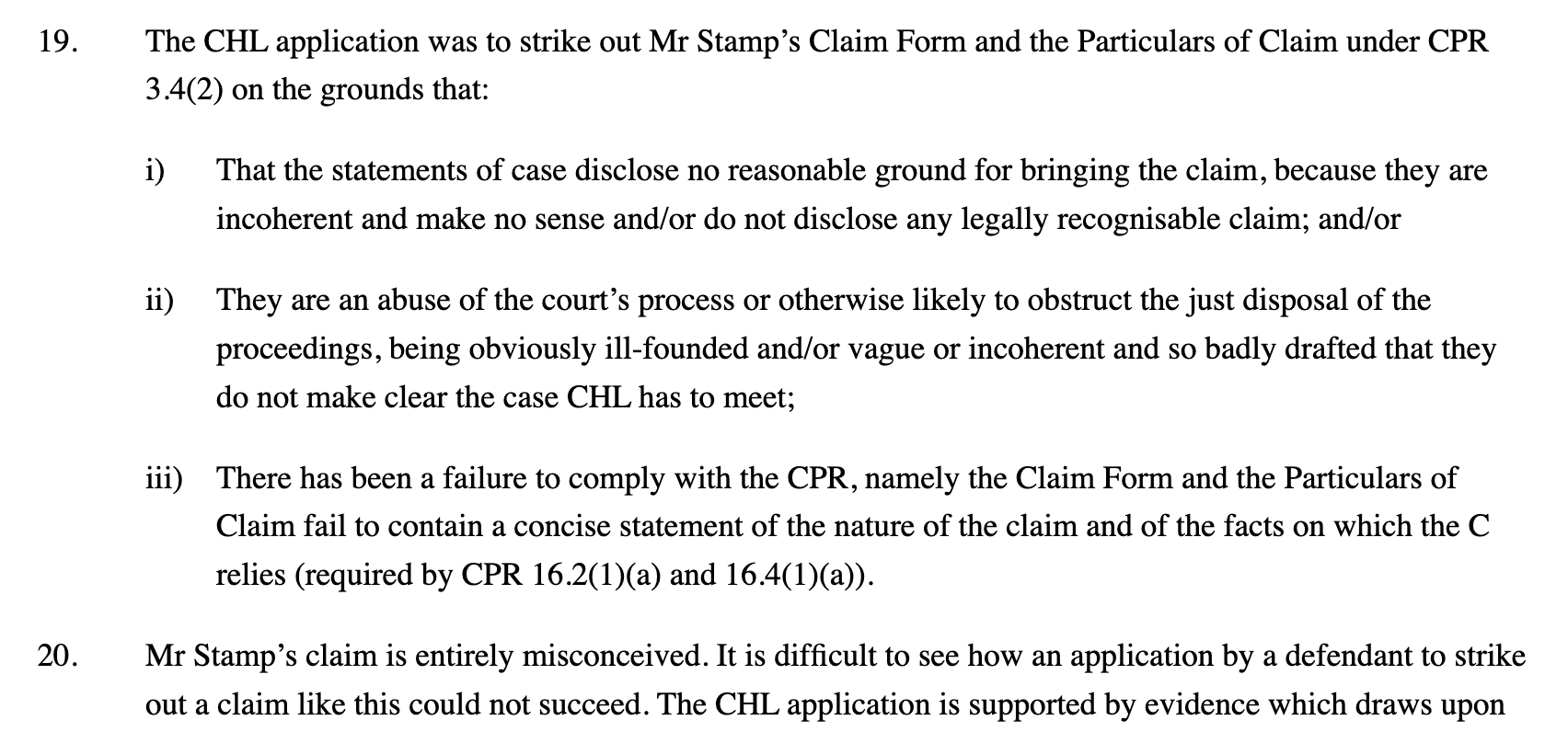

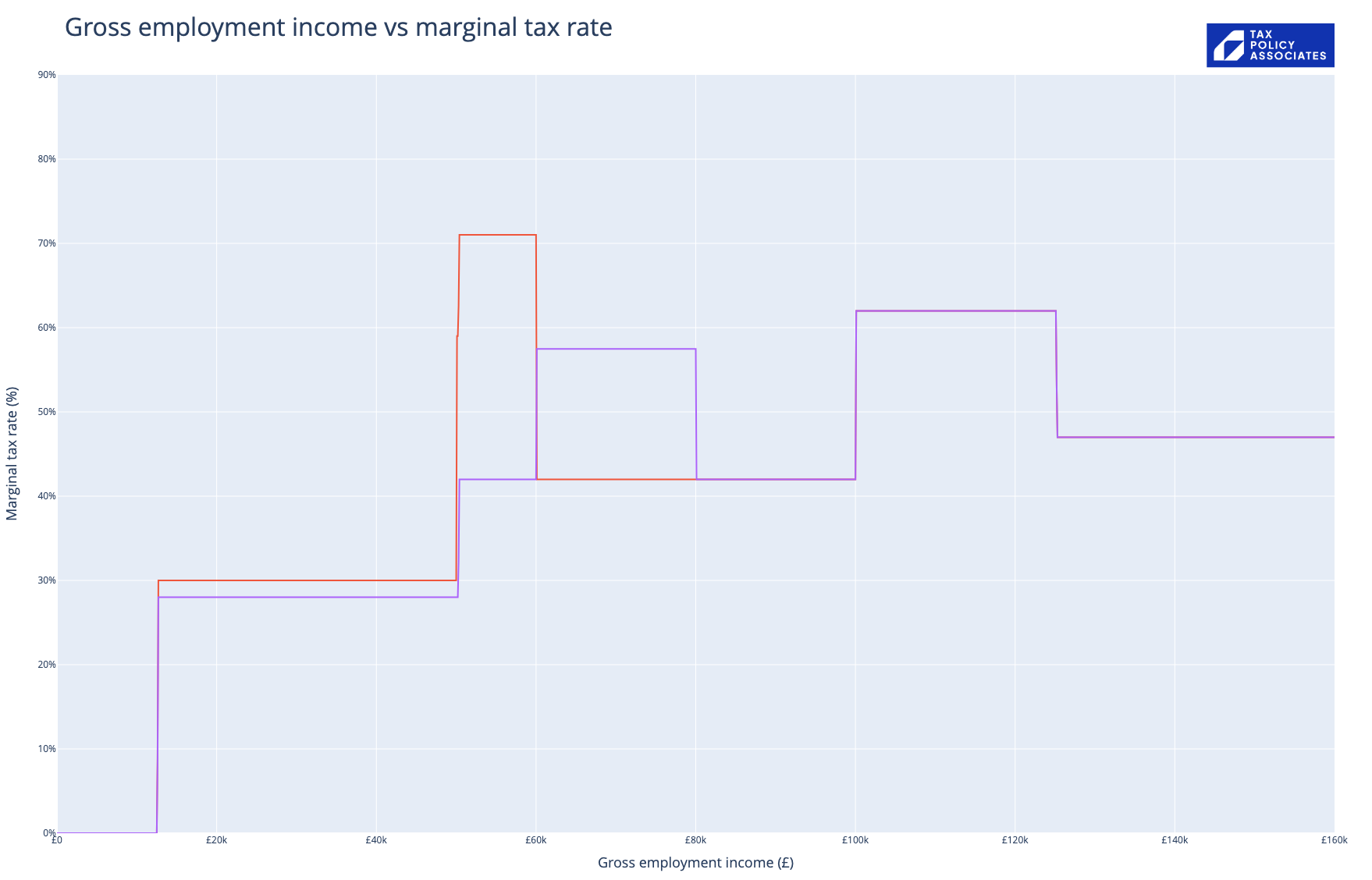

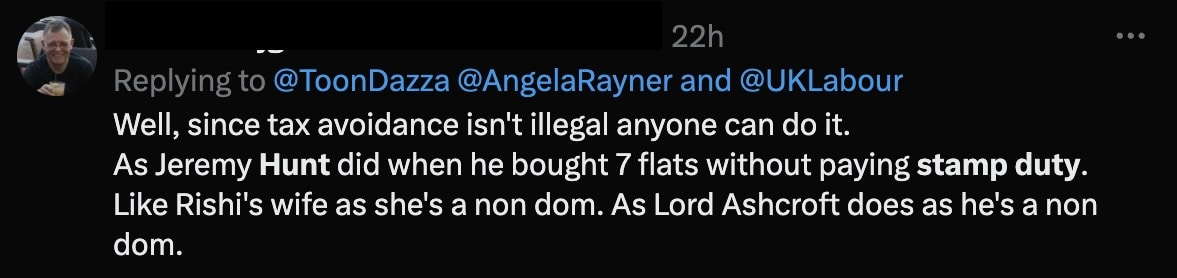

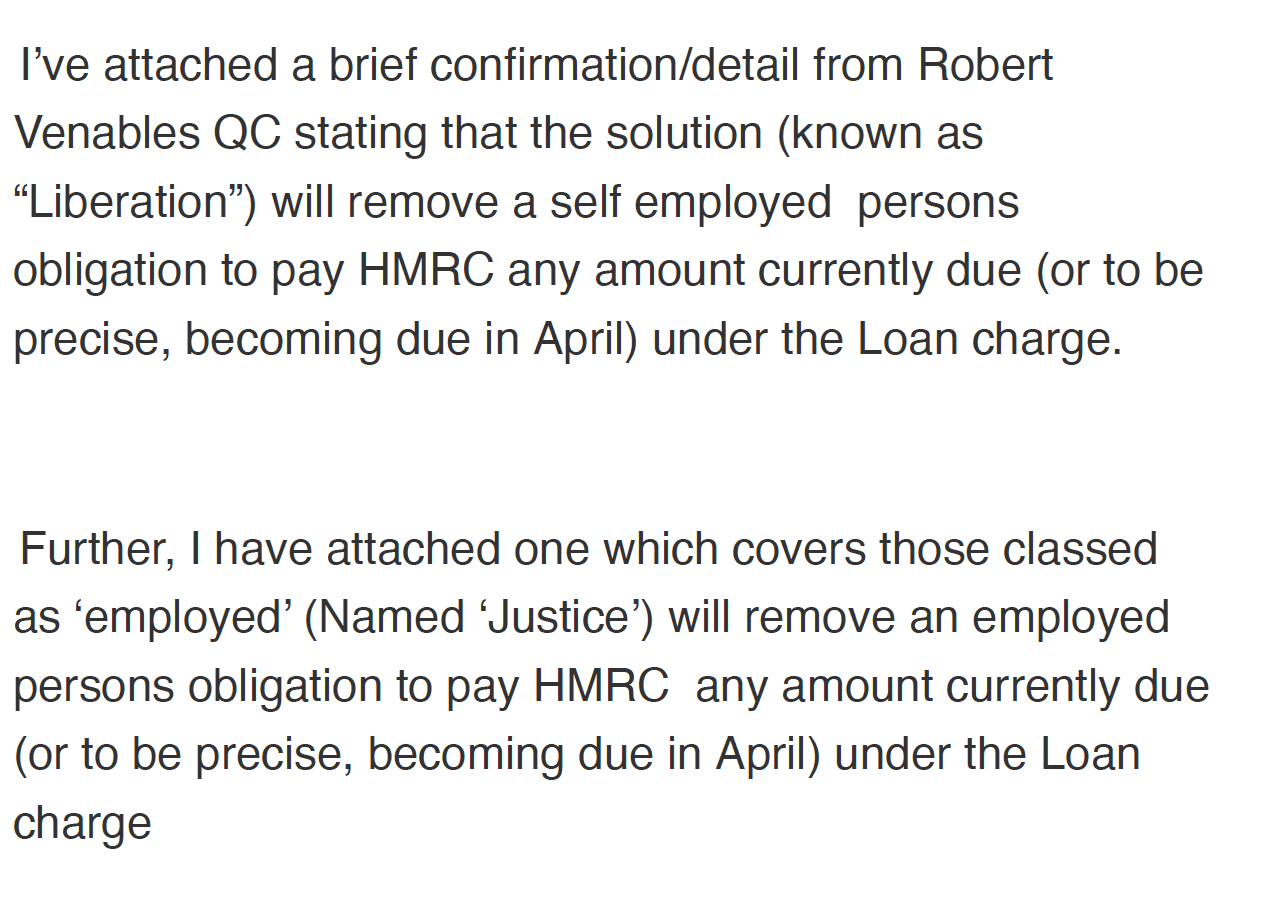

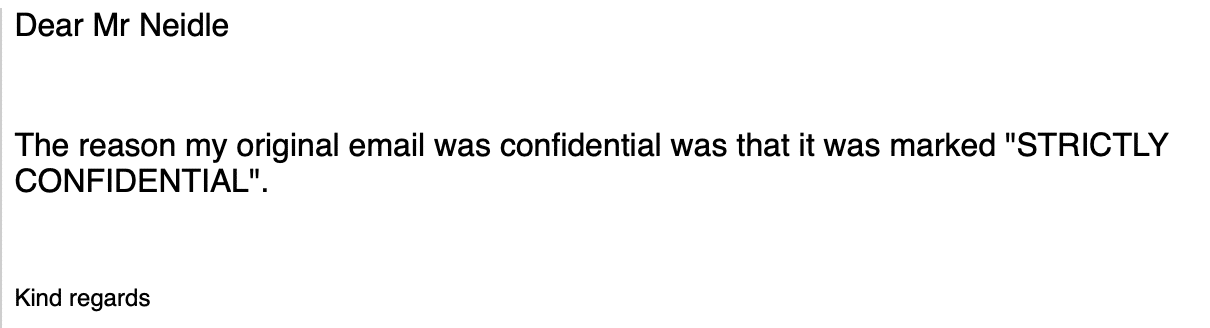

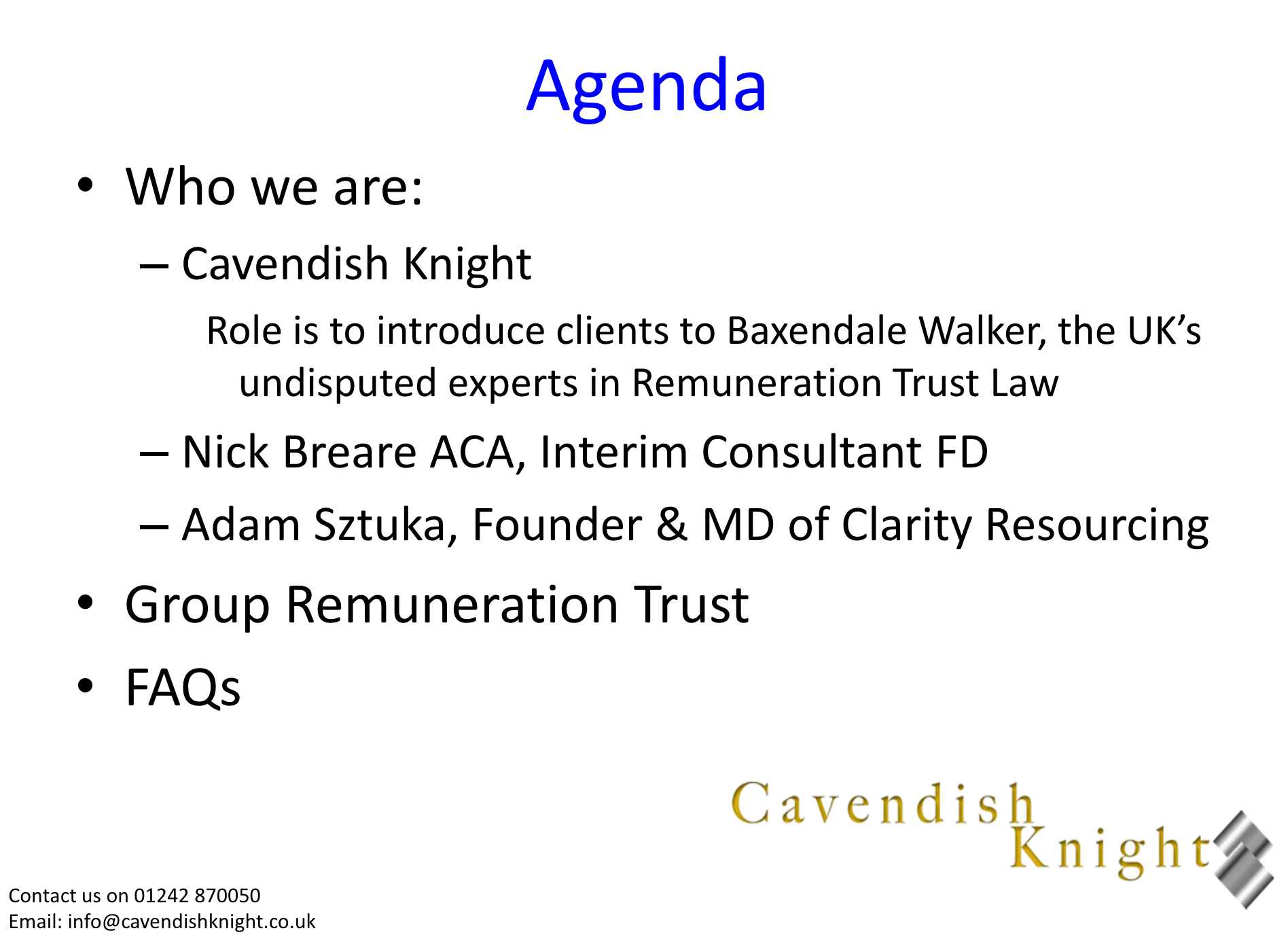

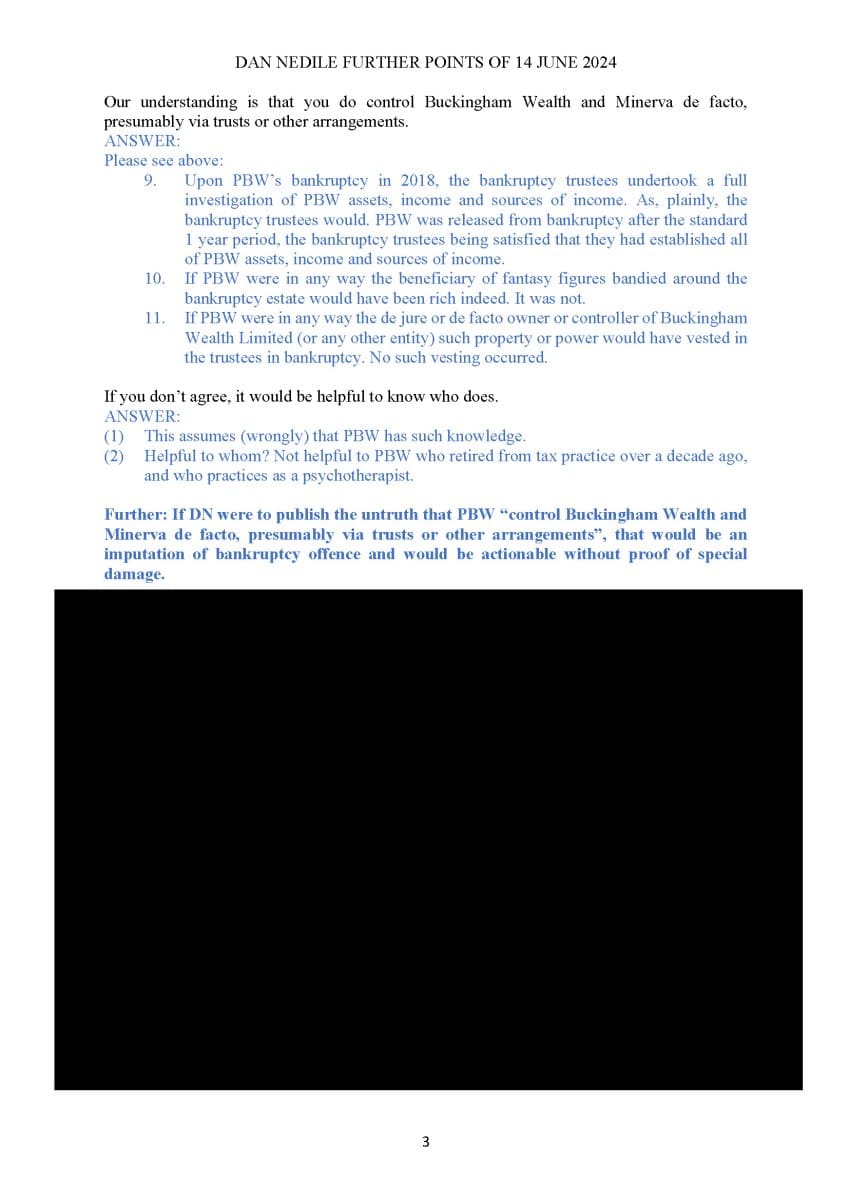

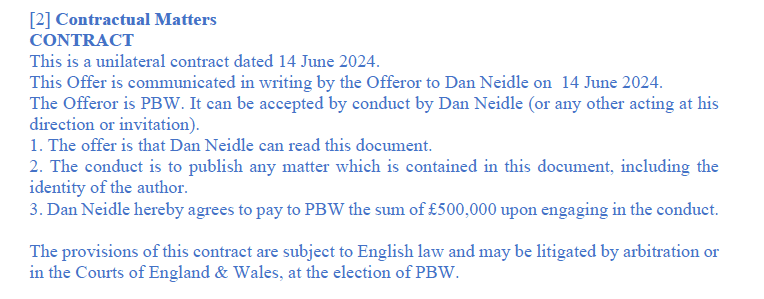

![27. This attempt to constrain my actions is wholly without merit; indeed it is childish game-playing.

28. I said in the prior email that I intended to publish any response; if PBW did not wish his words

to be published, he should not have replied to me.

29. Needless to say, PBW’s “offer” is not accepted. Whilst a contract can be accepted by conduct,

that is only if the conduct in question is intended to constitute acceptance. Here it is not (see

Reveille Independent LLC v Anotech International (UK) Ltd [2016] EWCA Civ 443)

30. In any event, the purported contract would fail for lack of consideration: I was free to read the

document and publish it as soon as I received it. I did not need PBW’s consent to do so.

31. I expect you agree with me on this. If not, please take this letter as a unilateral offer that you can

reply to this letter for a fee of £1bn, and you will accept that offer by conduct if you reply.](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-100.png)