Nadhim Zahawi has provided a series of unsatisfactory answers about his tax affairs. At least two are provably false (and one I characterised as a “lie” – something I do not do lightly). Another answer is, in my judgment, probably false.

This is a list of the nine outstanding questions, some of which are very serious, as they suggest that significant tax may have been due as a consequence of Mr Zahawi’s peculiar arrangements, but that this tax may not have been paid.

In summary:

- Why did Zahawi initially give a provably false explanation for the Balshore shares, that his father provided startup capital (I previously termed this, I think fairly, a “lie”)?

- Why did Zahawi subsequently give a second, different, explanation, that his father provided valuable advice in exchange for the shares? And why is it so contrary to common-sense, usual practice, and the evidence?

- If Zahawi’s second explanation is true, why was no VAT paid on the valuable services provided by his father to him?

- Why did Zahawi deny that he benefited from the trust, when we know that he did?

- Was this a tax avoidance scheme? If not, what was going on?

- When a UK person receives a gift from a trust, that is normally taxable. Did Zahawi pay UK tax on the gift from the trust? If not, why not?

- Zahawi says he took a loan from a Gibraltar company. He should have paid (“withheld”) UK tax on his interest payments. Did he?

- Why is that same loan not recorded in the Gibraltar company accounts?

- Zahawi has taken a series of loans from offshore companies. Were these funded from dividends and gains on the Balshore shares? If they were, did Zahawi pay UK tax on this?

I have drawn Zahawi’s advisers’ attention to this post, and I am hoping that they or he will respond.

1. Why did Zahawi initially give a provably false explanation for the Balshore shares (which I called, I think fairly, a “lie”)?

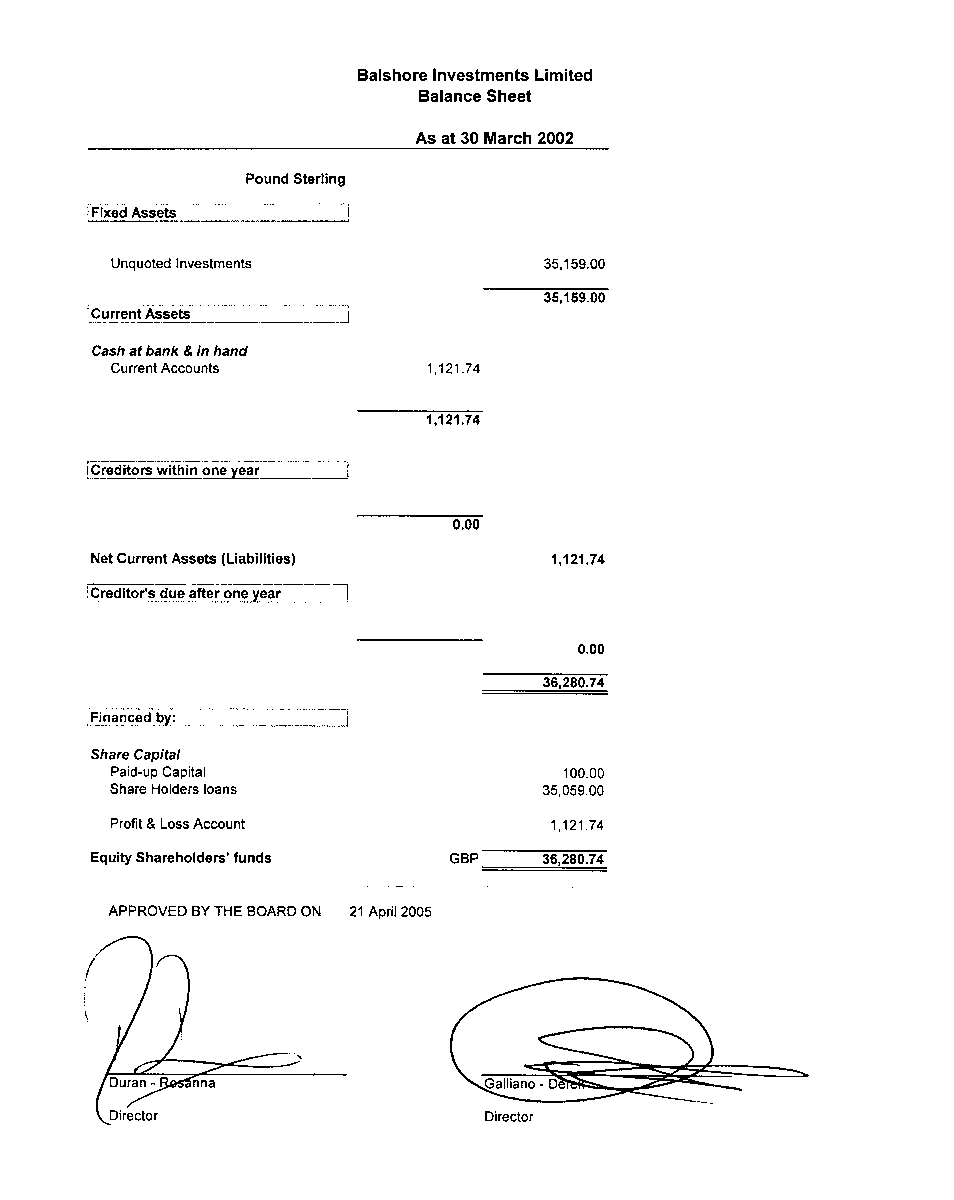

Zahawi and Stephan Shakespeare founded YouGov. Shakespeare held about 42.5% of the YouGov shares. But Zahawi held none. A Gibraltan company, Balshore Investments Limited, owned by a trust controlled by Zahawi’s parents, held 42.5% of YouGov. What was the reason for this unusual arrangement?

Following publication of my first report, and an FT article, Zahawi told several newspapers that the explanation for the Balshore holding was that, when Zahawi co-founded YouGov, he was not in a position to provide startup capital. His father therefore provided startup capital and took a shareholding in YouGov through Balshore.

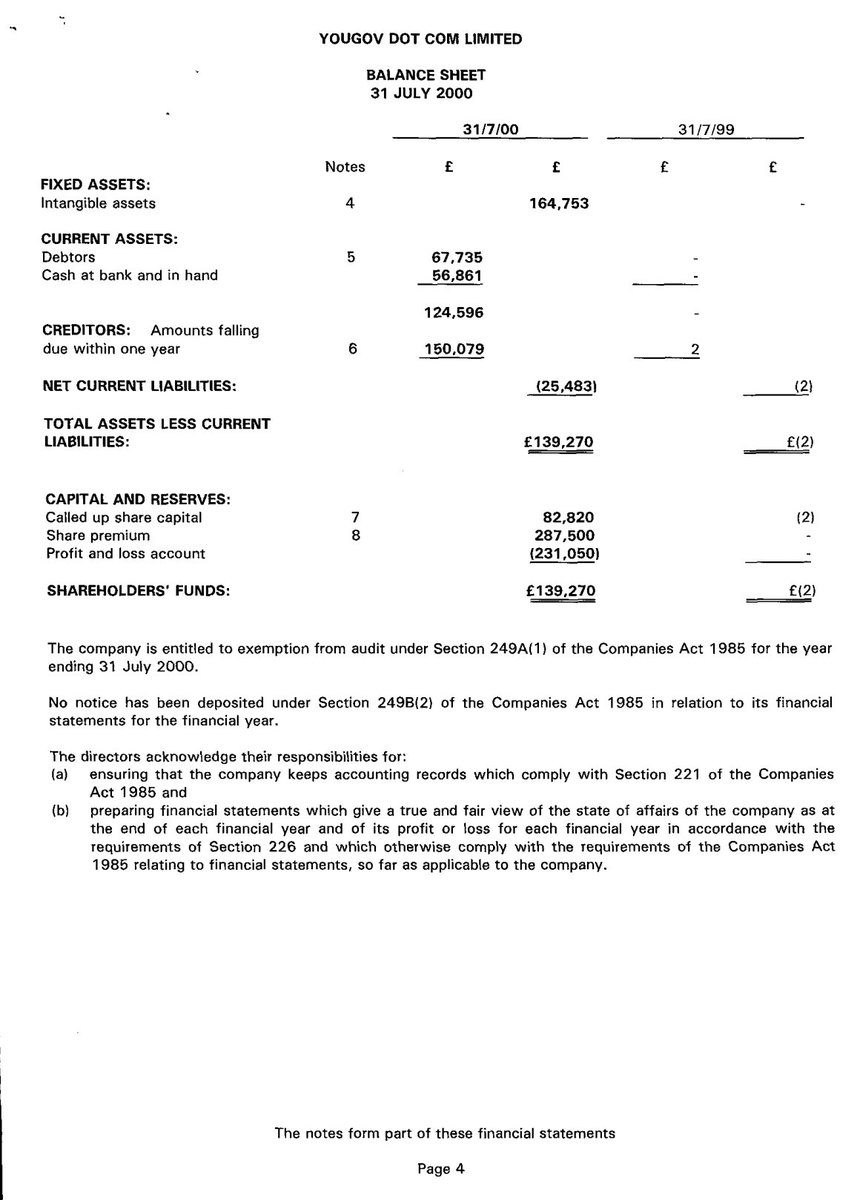

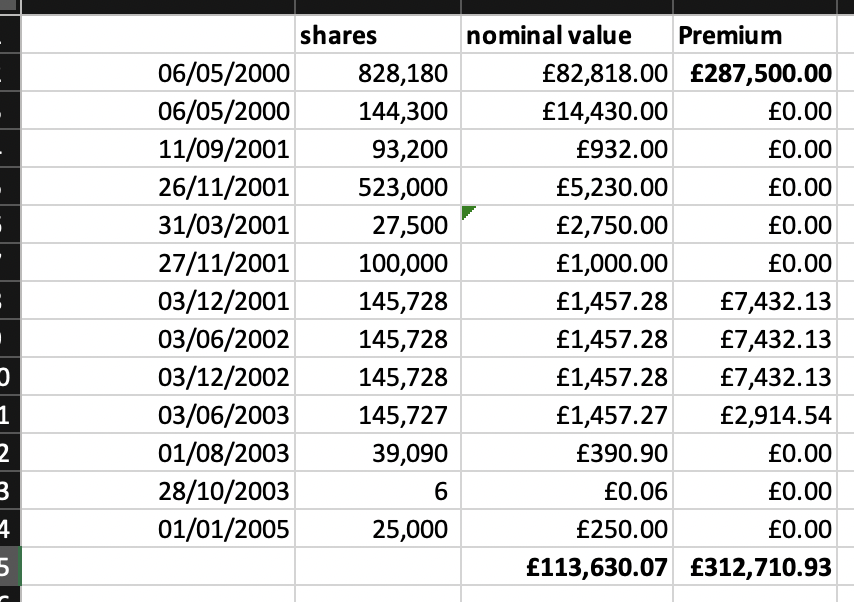

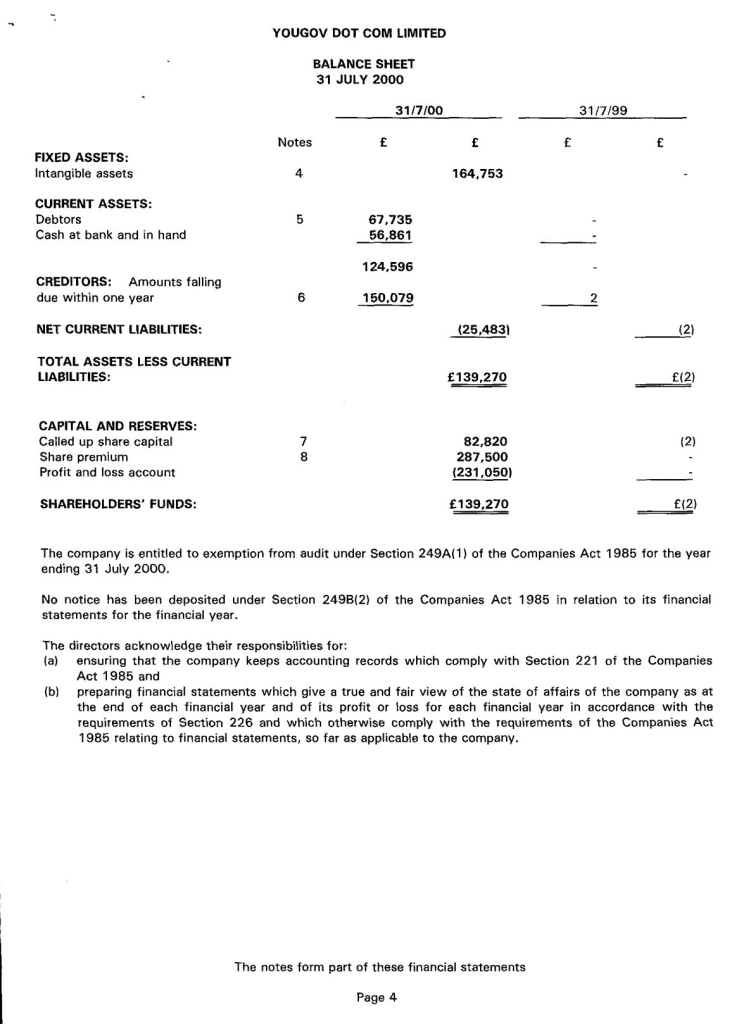

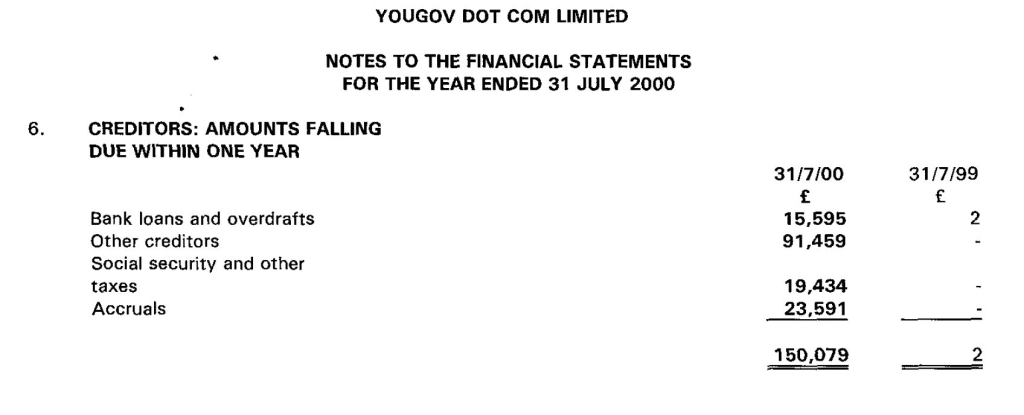

I investigated this at length and found no evidence that Balshore had provided startup capital. It may have paid £7,000 for its holding (although possibly this was two years’ later), but given that the other founding shareholder, Neil Copp, paid £287,500 for his shares, the £7,000 could not realistically be described as “startup capital”. And the pricing is wildly uncommercial: if Copp paid £287,500 for 15% of YouGov then somebody providing “startup capital” of £7,000 would receive less than 1%; not 42.5%.

Hence I concluded that either I had made a mistake, there had been a long-running mistake in YouGov’s filings and accounts, or Zahawi was lying. I invited Zahawi to comment. He did not. But, after I published my findings, Zahawi provided a different explanation (which I’ll refer to below). He did not suggest I had made a mistake, or that YouGov’s accounts and filings were wrong.

I therefore used the word “lie” to describe his first explanation because I drew a blank as to how else to describe someone saying something that was clearly untrue, and he surely could not have believed was true. Of course, I don’t know what was in his mind. But my question for Zahawi would be: if you really thought this was a true explanation – why? You surely know £7k isn’t startup capital (and if you don’t, then you should probably take another job). And what changed two days later that altered your belief?

Absent an explanation from Zahawi I will continue to describe his original, false explanation as a “lie”. I do not do so lightly. I have never before publicly described something as a “lie”, and I only did so after much consideration, and speaking with a variety of legal, tax, accounting experts.

My question for Mr Zahawi is: you presumably object to me saying that you lied. In which case: can you provide a credible explanation for why you said something that was provably false? If you can, I will of course withdraw my accusation. Otherwise, I will not.

2. Why did Zahawi subsequently give a second, different, explanation? And why is it so contrary to common-sense, usual practice, and the evidence?

Following publication of my refutation of his original explanation, Zahawi’s spokespeople started to brief journalists with a new and startling different explanation – that Zahawi had no experience of running a business at the time and so relied heavily on the support and guidance of his father, who was an experienced entrepreneur. His father had also provided Zahawi with financial support, as he had given up his job. It was for these reasons that Balshore received the shares. Startup capital was no longer mentioned as a rationale.

It’s naturally very plausible that Zahawi’s father provided him with advice, assistance, and financial support – what father wouldn’t? That, however, is very different in nature from the claim being made. The normal kind of parental advice and support would in no way justify receiving *all* the founder shares.

This second explanation seems unconvincing for a number of reasons.

- It contradicted the first explanation. In my experience, if a person raises one defence to an allegation, and responds to challenge by raising a second, different, defence, that suggests that both defences may be false.

- I have come across many successful entrepreneurs, both in my professional practice and socially. It was to be expected that a father would help his son with living expenses, and give him advice and assistance. In return he might receive some shares in the company (although this would be unusual). However, for him to receive the entire founding shareholding, and his son none, was inexplicable to me. I spoke to several entrepreneurs of my acquaintance, and they agreed with my conclusion.

- One of the hallmarks of generational wealth planning, whether or not it involves tax avoidance, is that it involves passing wealth down the generations. Zahawi’s father, as a successful businessman, would surely have been familiar with this. For the son to make a gift to the father was contrary to usual practice.

- If Zahawi’s father had been as involved as Zahawi now claims, he could well have been a “shadow director” for company law purposes – “a person in accordance with whose directions or instructions the directors of the company are accustomed to act”. This would have undesirable consequences for Zahawi’s father and for YouGov – whilst a startup might not be aware of these issues, I expect that they would have been identified and disclosed in the run-up to YouGov’s IPO in 2005. They were not.

- It is unclear to me from a company law perspective that it is permissible for a company to issue shares at an undervalue to someone who has provided *no value* to the company. If Zahawi’s story was true, the shares would have been issued to him as a founder (in the usual way) and he would have gifted some (or, just about possibly, all) of the shares to his father (but see below).

- I searched through other YouGov documentation, news reports, and Zahawi’s own description of his time at YouGov, and could find no evidence of his father having been involved. He could of course still have been involved providing advice to Zahawi behind the scenes (as I would expect any father with business experience to have done), but that did not support the claim that the support was so invaluable as to justify Zahawi’s father receiving all the founder shares.

- I discussed these matters with journalists from The Times. They spoke to employees who had worked at YouGov in its early years; they had no recollection of Zahawi’s father being in the office and were surprised to hear of his alleged involvement with the business. YouGov then provided an official statement:

“To YouGov’s knowledge, YouGov had/has no association with Hareth Zahawi beyond any interests he may have held/holds in Balshore Investments Ltd in its capacity as a YouGov shareholder”

After the publication of The Times‘ article, Peter Kellner, who joined Zahawi and Shakespeare after YouGov’s founding, wrote:

“For the record, I met Hareth Zahawi during YouGov’s early months. I recall his similarity in appearance to Ariel Sharon. Although he had no formal role in the company’s operations, it was clear that his advice and experience were helpful to Nadhim and, through Nadhim, to YouGov”

Joe Twyman, an early YouGov employee, wrote:

“I also remember meeting Nadhim’s father on a few occasions during the early years of YouGov. I always found him to be an extremely friendly and kind man.”

I regard both as consistent with the reports in The Times. They are also consistent with my previous view; that Zahawi’s father may have provided him help and support behind the scenes, but it is very unlikely that was to the degree that would justify receiving all of Zahawi’s founder shares. “Helpful” seems a long way from sufficient. Hence I regard Zahawi’s second explanation as most likely false (by contrast, I am almost certain that the first explanation was false).

My questions for Mr Zahawi are therefore: do you acknowledge how unusual it is for a founder share to be issued to someone who is not a founder, and for the actual founder to receive no shares? How do you answer the points above? Do you have any actual evidence that your father’s support was so significant that it justified the extraordinary step of him taking all of your founder shares?

3. If Zahawi’s second explanation is true, why was no VAT paid on the valuable services provided by his father to him?

Let us suppose for the moment that Zahawi’s explanation for the Balshore shares is correct. His father provided him with help, advice and support that was so extensive that it justified Zahawi giving all of the founder shares in YouGov (that would ordinarily have been his) to his father.

People often think a gift has no UK tax consequences – and inheritance tax and capital gains tax aside, that is generally true. However, sometimes a gift is not a gift.

If I provide you with free legal advice, that will have no UK tax consequences for you. But if I provide you with free legal advice, and you then make a gift to me of £5,000, then it’s pretty clear that these were not gifts at all. In reality what happened was that you paid me £5,000 for legal advice – and that will have tax and VAT consequences. By “pretty clear” I meant that this is the technical UK tax and VAT result, but also that I think most non-specialists would be unsurprised that this is the result.

And that is of course what happened here. Zahawi’s father made him the “gift” of substantial advice and assistance. In return, Zahawi gave his father the YouGov shares (or, to be more precise, caused the Balshore shares to be issued to his father’s subsidiary at a considerable undervalue).

I expect this means that UK VAT was chargeable on the value of the services provided by Zahawi’s father. Naively, if Neil Copp paid £287,500 for 15% of the shares, then the value of Zahawi’s 42.5% stake was over £800,000 – and if Zahawi’s story is correct then this is our starting point for the value of the services his father provided.

The VAT rate at the time was 17.5% – so we should have expected one of Zahawi, his father and YouGov to account for somewhere in the region of £140,000 of VAT. I doubt very much they did. Why?

There are four possible explanations:

- There is a technical reason why VAT did not apply which I am missing (I have considerable VAT expertise but would not say I was one of the leading advisers in this area).

- The parties intentionally conspired not to pay VAT that was due – i.e. criminal tax evasion. That seems highly implausible.

- VAT did not technically arise because Zahawi’s father did not in fact provide material value, and Zahawi’s explanation is false.

- This was a poorly implemented tax avoidance scheme, and the consequences were not thought through.

Many people will think the concept of a “poorly implemented tax avoidance scheme” is odd, so I should explain this.

I am familiar with the tax avoidance schemes the Big Four and others created in the 2000s. They were generally carefully constructed and implemented, with legal documentation created to support the scheme and minimise the risk of it failing. This scheme looks amateurish by comparison. There appears to be no documentation at all justifying Balshore’s receipt of the shares. Hence I expect that Mr Zahawi received very limited tax advice when the scheme was put in place (unsurprising given his relatively limited resources at the time). Perhaps it even arose from a casual suggestion from a relative or friend, and no adviser was involved at all – but that is pure speculation on my part.

The amateur nature of the planning means that mistakes may have been made which meant that, far from avoiding tax, the trust actually triggered a series of undesirable tax consequences. This VAT could be one of those consequences. There may be others, which I discuss below.

So my question for Mr Zahawi is: was VAT payable on the valuable services you say your father provided? Did you pay it? If not, why not?

4. Why did Zahawi deny that he benefited from the trust, when we know that he did?

Zahawi responded to initial reports by saying (in an interview with Sky News on 11 July):

“There have been claims I benefit from an offshore trust. Again let me be clear, I do not benefit from an offshore trust. Nor does my wife. We don’t benefit at all from that.”

Later in the same interview, the discussion turned to Balshore. The transcript is as follows:

Burley: You or your company once held £20m of YouGov shares in a Gibraltar-based company. What was the reason for using offshore financial structures like this, if not for the purpose of avoiding tax?

Zahawi: I was not the beneficiary of the Balshore investment that held those shares.

Burley: Who was?

Zahawi : My family. It’s the public record – my father.

On 17 July, Zahawi’s spokesman repeated the denial to the Guardian:

“Nadhim and his wife have never been beneficiaries of any offshore trust structures.”

However, all of this is false. Zahawi has demonstrably benefited from the trust and been a beneficiary of the trust (both as the terms “benefit” and “beneficiary” are used in ordinary language, and within their technical tax/legal meanings).

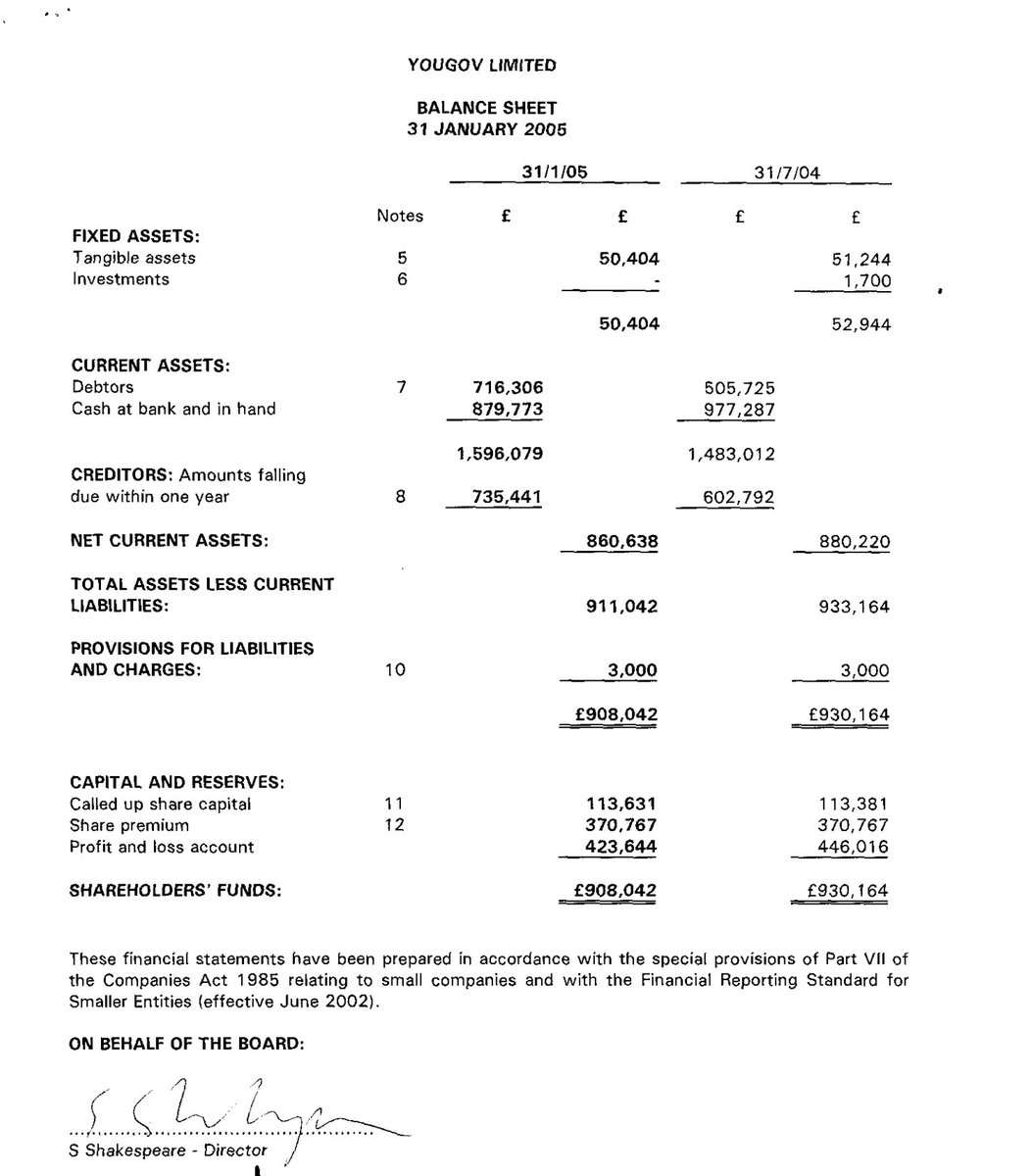

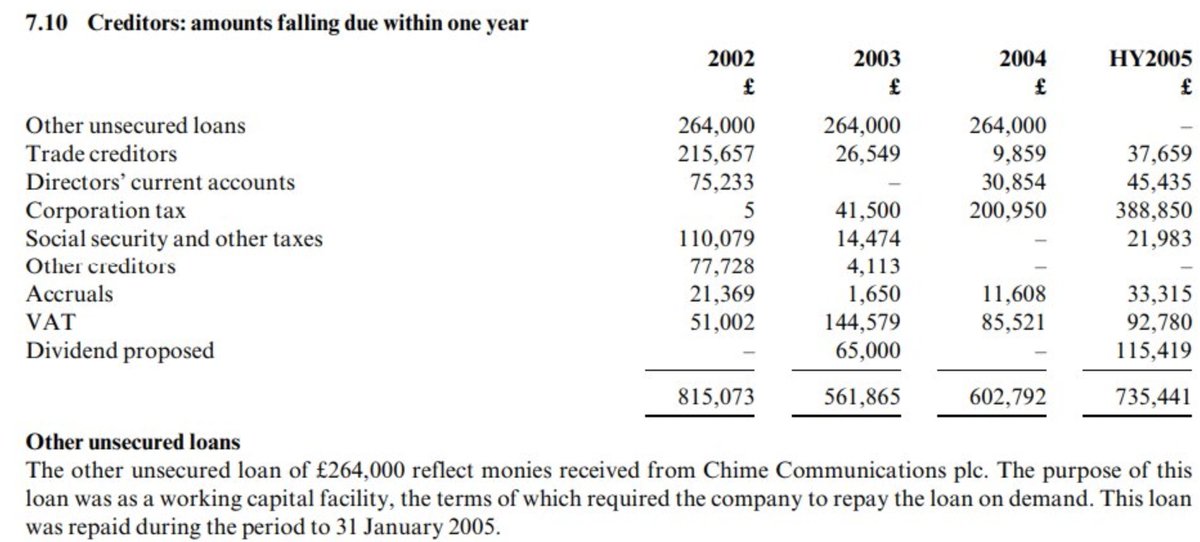

In 2005, a YouGov report disclosed that a number of loans had been made by YouGov to its directors in contravention of the provisions of the Companies Act 1985. Balshore agreed that a dividend on its shares could be used to repay some of the loan. Zahawi’s spokesman has described this as a gift to Zahawi from his father – that is accurate. I believe most people would say that was a “benefit” from the trust (given Balshore was controlled by the trust), and therefore that Zahawi was a beneficiary. Furthermore, and importantly, from a UK tax perspective, a person receiving a gift from a trust, or a company controlled by the trust, is receiving a benefit from the trust, and (absent a breach of fiduciary duty by the trustees) is a beneficiary of the trust.

Zahawi’s statements that he does not benefit from the trust, and has never been a beneficiary, are therefore false. It is hard to understand why he is making them. He must be aware that he benefited from the trust in 2005 (and possibly on other occasions as well). Whether he is setting out to lie, or attempting to carefully word his responses to avoid revealing the truth, is to my mind of little consequence. Both are forms of deception.

If Mr Zahawi disagrees, then he will have to explain how receiving a gift from a subsidiary of a trust is not a “benefit” – although I confess I do not see how he can do this. The obvious next question is why, then, he made a denial that was false, and that he knew was false.

The other obvious question is: if Mr Zahawi falsely denied a benefit that is a matter of public record (albeit only found after some digging), then what other benefits did he or his family receive that are not a matter of public record? What assurances can Mr Zahawi give that he has received no other gifts, loans, or other funds from the trust and its companies? How can we believe them, after the previous false denial?

5. Was this a tax avoidance scheme? If not, what was going on?

Whether something is a tax avoidance scheme is a question of judgment – there is no single legal definition. However, I would say that it is a scheme if it (1) results in a reduced tax liability compared with what would normally have happened, whilst (2) does not fundamentally change the economics from what would normally have happened, and (3) has no obvious commercial rationale.

In this case, there is clearly reduced tax liability – dividends and gains that would have been taxed were they received by Zahawi, were not taxed when received by his father. If that was all that happened then this would not be a tax avoidance scheme – it would simply be a gift from Zahawi to his father (albeit a very unusual one). The economics would have fundamentally changed because what would have been Mr Zahawi’s property instead became his father’s.

However we have reason to believe that at least some of the benefit of the untaxed dividends and gains were returned by Balshore, and/or Berkford to Zahawi, whether by gifts or loans. At this point it does look like a scheme – because it is putting Zahawi in the same position as if he had received the dividends/gains, but without paying tax on them. The degree to which it is an avoidance scheme will depend upon how great the gifts/loans were.

Mr Zahawi is adamant this is not a tax avoidance scheme. But why? Where funds derived from dividends/gains on the shares are provided to him, and he pays no tax on that receipt, he has very literally avoided tax on what would otherwise have been his dividends and gains.

We also have to return to the absence of a credible rationale for Balshore receiving the shares. Uncommercial and inexplicable transactions are typical hallmarks of tax avoidance schemes.

6. Did Zahawi pay tax on the gift from the trust? If not, why not?

When a trust (or a company under its control) makes a capital payment to a UK person, that person is considered a UK beneficiary of the trust. The payment is taxable in the hands of the recipient, and the trust itself has to file UK tax returns. The 2005 gift to Mr Zahawi was therefore almost certainly taxable (probably as a capital payment from a trust, but the precise basis will depend upon the precise facts, which I do not have; however it is overwhelmingly likely the payment was taxable).

So: did Mr Zahawi declare the 2005 gift to HMRC and pay tax on it? If not, on what basis? Has the trust been filing UK tax returns?

It is important to note that failure to pay tax that is due is not tax avoidance. It is simply a breach of the law. If intentional, it would be criminal tax evasion – although in this instance I expect that this was simply a badly implemented tax avoidance scheme, and Mr Zahawi and the other participants did not understand the consequences of what they had done.

Did Mr Zahawi and his family receive other gifts, loans, payments or other benefits from the trust and the companies associated with it?

7. Zahawi says he took a loan from a Gibraltar company. He should have paid (“withheld”) UK tax on his interest payments. Did he?

Mr Zahawi acquired the Oakland Stables in Warwickshire in 2011 for £875,000. At the time, it was reported that he acquired the property with a secured loan from Berkford Investments Limited (Berkford), which I believe to be owned by the same trust as Balshore. Zahawi asserted that this was a commercial loan

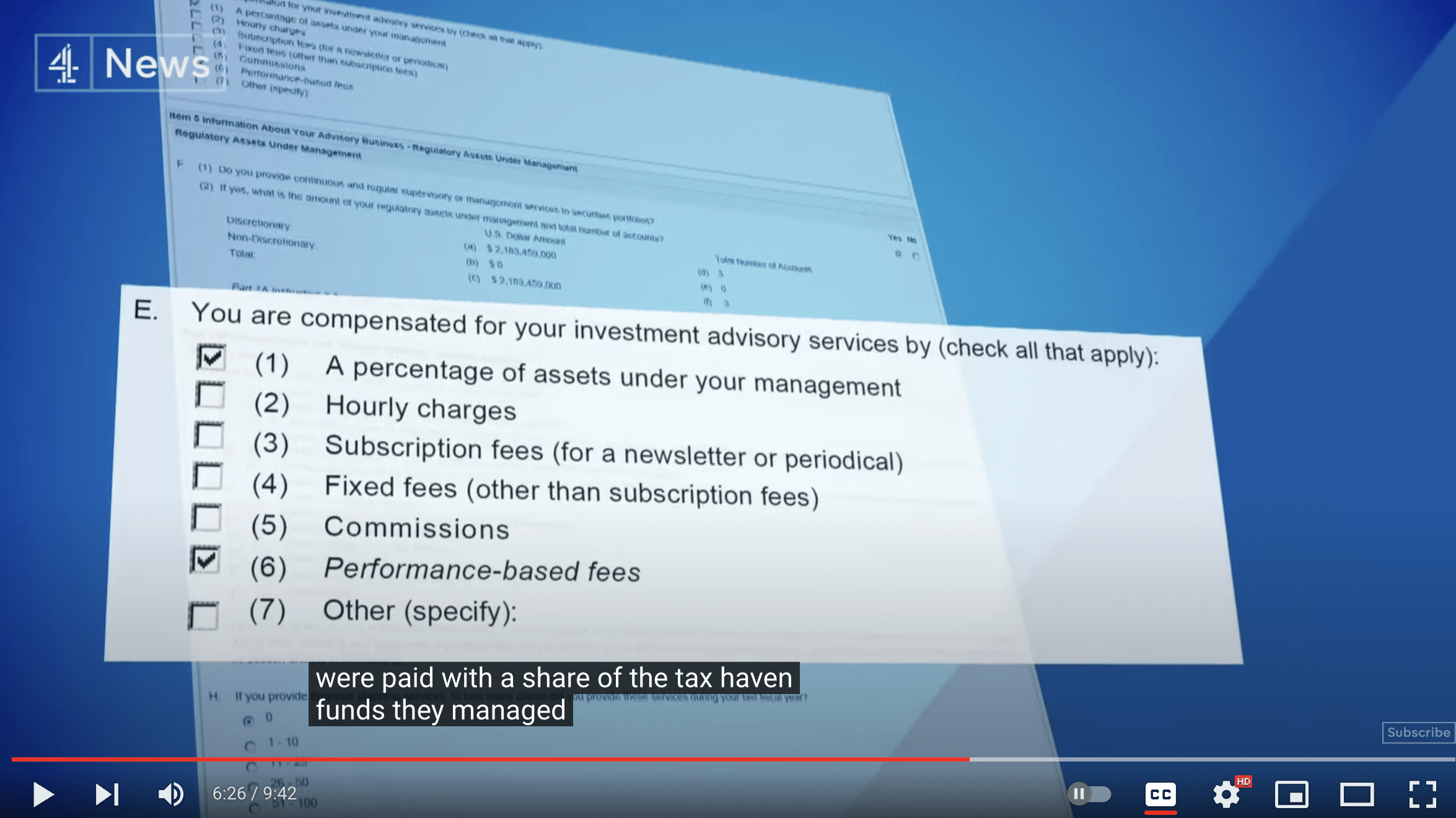

In my experience, UK residents do not ordinarily borrow from Gibraltar companies, because the UK applies a 20% withholding tax on interest payments to Gibraltar (in the way it would not for interest payments to e.g. Ireland). The tax adds an additional cost that most borrowers and lenders would not regard as commercially palatable. This is a very simple tax point, that I would expect a competent trainee lawyer or trainee tax accountant to be able to identify.

So my question is, for the eleven years the loan has been in place, has Zahawi been withholding tax from the interest and accounting for it to HMRC?

Failure to do pay the tax would again not be tax avoidance; it would simply be a breach of the law. If that failure was intentional it would amount to criminal tax evasion. Again, if this occurred, I expect it was a consequence of a badly implemented tax avoidance scheme, and the participants therefore not understanding the tax consequences of what they had done.

8. Why is that same loan not recorded in the Gibraltar company accounts?

In 2010, 2011 and 2012, Berkford’s tangible assets were £3.2m, with debtors of £100. The Oakland Stables loan should have increased the debtors by a material amount over this period – but it did not. Nor is there any obvious correction in subsequent periods. I have posted the relevant documents here. The full Berkford accounts are here.

It is possible that the accounts are wrong (although to miss several hundred thousand pounds for ten years would be extraordinary). It is also possible that a peculiar accounting methodology was adopted for some reason (although the accountants I have spoken to view that as unlikely).

The other possibility is that Berkford did not regard this as a loan, but a gift. The land registry entry was made so that the arrangement appeared to be a loan from the UK “side”, but the parties did not consider that the Gibraltar accounts of Berkford would become available. That would (if it resulted in tax not being paid) take us into the territory of criminal tax evasion. However I find it hard to believe that Mr Zahawi would engage in this kind of conscious, and rather involved, deception, and therefore I shy away from this explanation as well. [Update: a commentator below makes the excellent point that a gift would also have depleted the balance sheet, meaning this scenario also involves error or fraud in Berkord’s accounts. So I would now regard this explanation as even less likely]

So my question for Mr Zahawi is: why is the Oakland loan not in Berkford’s accounts.

I appreciate he will have to ask his father to ask the law firm running Berkford. However, given how peculiar this looks, I trust he will see that it is an important matter to clear up.

9. Zahawi has taken a series of loans from offshore companies. Were these funded from the Balshore shares? If they were, did Zahawi pay UK tax on the loans? If not, could the loan charge apply?

It appears that a property company controlled by Mr Zahawi and his wife, Zahawi and Zahawi Ltd, has received perhaps £29.8m of unsecured loans. In my experience, commercial real estate lending is almost always made on secured basis (i.e. secured over the real estate). Hence my expectation is that these loans are not commercial, and therefore that they were made by a related party – perhaps Balshore or Berkford.

My question for Mr Zahawi is: were these loans, or any others to Mr Zahawi, his wife or their companies, made on or after 9 December 2010, funded directly or indirectly from dividends or gains on the YouGov shares held by Balshore?

If they were, and the loans were made on or after 9 December 2010 then the disguised remuneration rules in Part 7A ITTEPA 2003 may apply, with the principal of the loans then taxable as PAYE income. If HMRC is outside the normal limitation period, and reasonable disclosure was not made to HMRC at the time, then the loan charge in Schedule 11 Finance (No. 2) Act 2017 would apply; the loans would again (speaking broadly) be taxable as PAYE income.

Mr Zahawi will be aware that the loan charge was, and remains, highly politically controversial, within Parliament and outside. The suggestion that the Chancellor himself could be subject to it is likely to be greeted with general astonishment. I would therefore urge Mr Zahawi to be as clear as possible whether any loans to him, his wife, or their companies were funded directly or indirectly from the YouGov shares.

Why does this matter?

As I said when I first wrote about Mr Zahawi, the public has a right to know if there are specific and obscure provisions of the tax code from which the Chancellor personally benefits. The public interest is even more powerful if it appears likely that the Chancellor, who is ultimately responsible for HMRC, will be the subject of an HMRC investigation. All the more so if, as I believe is the case, there are credible reasons to believe that the Chancellor has provided a series of false answers about his tax affairs.

These questions in large part result from help and assistance I’ve received from tax lawyers, tax accountants, commercial lawyers and entrepreneurs. I am immensely grateful for all of their help. If you have any further thoughts, please do post comments below, or contact me.