I reported in July that Nadhim Zahawi, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, had founded YouGov using a tax avoidance structure. Zahawi provided an explanation which my detailed analysis showed to be false. Zahawi then shifted immediately onto a different explanation. In my opinion this showed that his first explanation was a lie – and I said so.

Zahawi had a media profile and resources dwarfing a small tax think tank – but instead of using these to explain himself, he instructed Osborne Clarke to write to me demanding that I retract. And their letter claimed that I could not publish the letter, or even tell anyone I’d received it. It was an attempt to silence criticism which had no basis in law, and for which Zahawi and his lawyers should be ashamed.

The Solicitors Regulation Authority this week issued a “warning notice” making clear that this kind of behaviour is unacceptable. I have therefore referred Zahawi’s lawyers, Osborne Clarke, to the regulator.

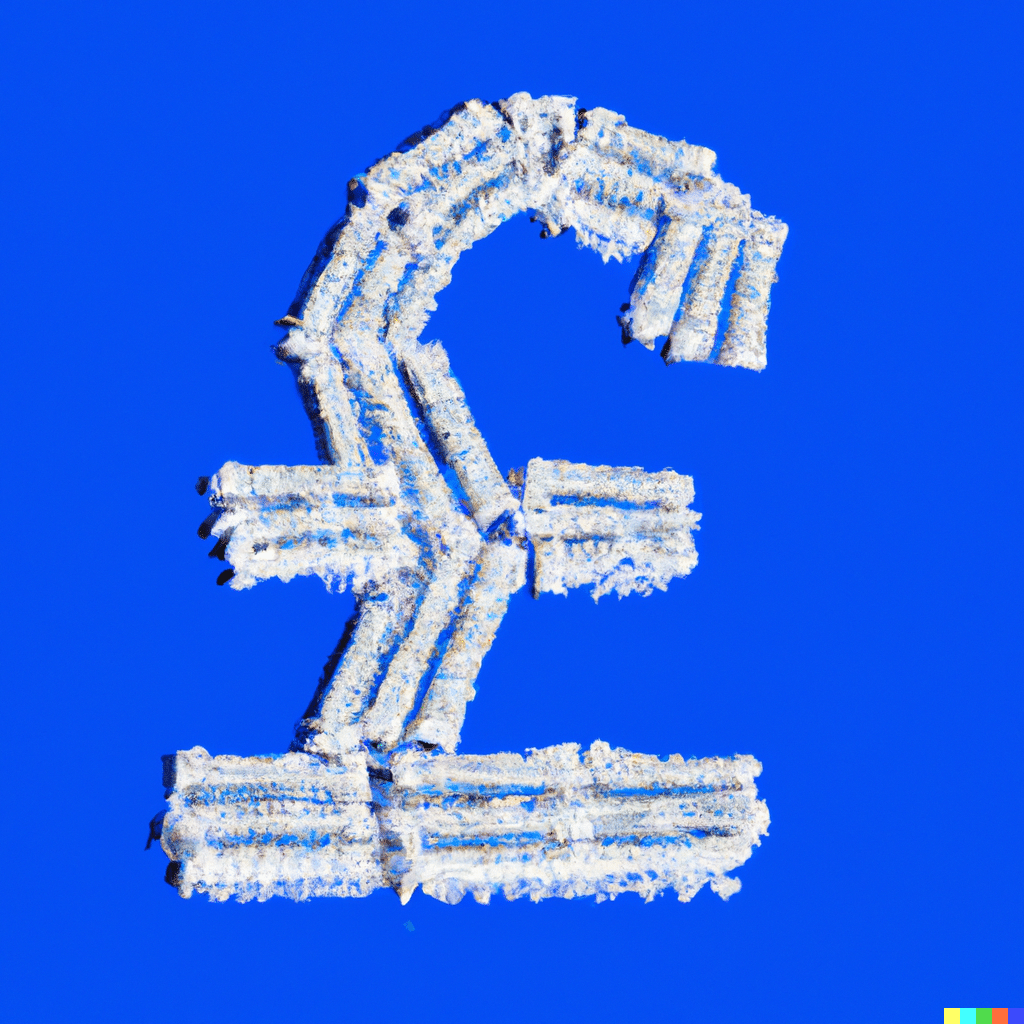

I’m also asking the SRA to investigate Osborne Clarke more widely. In the end, their actions cost me some legal fees but otherwise failed. But I know there are many others, without my legal background, contacts or financial resources, who have received letters like this (on behalf of Zahawi and others) and been silenced. If the SRA find that people have been silenced by deception and intimidation, then this needs to be put right.

I’ve copied below the text of my letter, with links to the referenced documents. If you prefer a PDF, that is here (but without links).

And more on Mr Zahawi coming soon…

SRA General Counsel

The Cube

199 Wharfside Street

Birmingham B1 1RN

1 December 2022

Sent by email

Dear Ms Oliver

Osborne Clarke – SLAPP – breach of SRA Principles

1. Many thanks for your publication on 28 November 2022 of the new warning notice on SLAPPs. In light of that notice, I wish to make a formal referral to you of Osborne Clarke for several significant breaches of SRA Principles. I believe you will be already aware of a number of the breaches, but you may not be aware of others.

The background

2. I retired from commercial practice in May 2022, and founded Tax Policy Associates; a think tank which works to improve both tax policy and the public understanding of tax. In July 2022, I wrote several articles and social media posts about Nadhim Zahawi. At that time, Mr Zahawi was the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

3. The essence of my writings was that, when Mr Zahawi founded YouGov in 2000, the founder shares (which ordinarily would have been issued to Mr Zahawi) were instead issued to a Gibraltar company, Balshore Investments Limited. I said this looked like tax avoidance. Mr Zahawi’s team responded by briefing several journalists that the reason for Balshore receiving the shares (which I will call the “first explanation”) was that Mr Zahawi’s father, who owned Balshore, had contributed startup capital to YouGov.

4. I investigated the accounts and Companies House filings and found that the startup capital was contributed by another investor, Neil Copp. Balshore had contributed only a token amount (£7,215). I therefore wrote that either I was mistaken, the filings were wrong, or Mr Zahawi was lying. The key Twitter thread can be found at https://taxpolicy.org.uk/evidence (attached in PDF format as tweet1.pdf).

5. Immediately after this, Mr Zahawi’s team started briefing a different explanation (which I will call the “second explanation”): that Mr Zahawi’s father received the shares in recognition of the significant advice and assistance he had provided to the business. The fact that Mr Zahawi was no longer defending his first explanation suggested to me that I had not made a mistake; in my opinion it suggested that the first explanation had been a lie. I said so. I did not say that the second explanation (“advice and assistance”) was a lie (although it seemed highly implausible). The key Twitter thread can be found at https://taxpolicy.org.uk/lying (attached as tweet2.pdf).

6. On Saturday 16 July 2022, I received an unsolicited direct message on Twitter from Ashley Hurst, a partner at Osborne Clarke (see attachment SRA1). Mr Hurst sought to speak to me on a without prejudice basis. I responded that he should put what he had to say in writing, and that I did not accept without prejudice correspondence.

7. Later that day I received an email from Mr Hurst (see attachment SRA2) asking me to retract my accusation by the end of that day, or I would receive an open letter on Monday.

8. I did not retract. On Tuesday 19 July I received a letter from Mr Hurst (see attachment SRA3).

Breaches of SRA Principles

9. The Osborne Clarke correspondence bears several of the hallmarks of strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) which are identified in your warning notice.

Labelling

10. The email (SRA2) is marked “confidential and without prejudice”. It says:

“I have marked this email without prejudice because it is a confidential and genuine attempt to resolve a dispute with you before further damage is caused. Our client wants to give you the opportunity to retract your allegation of lies in relation to our client.

That would not of course stop you from raising questions based on facts as you see them.

You have said that you will “not accept” without prejudice correspondence. It is up to you whether you respond to this email but you are not entitled to publish it or refer to it other than for the purposes of seeking legal advice. That would be a serious matter as you know. We recommend that you seek advice from libel lawyer if you have not done already.”

11. However, the letter cannot possibly be “without prejudice”, for three (independent) reasons. First, I had specifically told Osborne Clarke I would not accept “without prejudice” correspondence. Second, even if I hadn’t done so, their email was not a genuine attempt to resolve an existing dispute – it offered no concessions, and was therefore not an attempt at settlement. Third, there was no dispute – as became subsequently clear, Mr Zahawi never had any intention of instigating a claim.

12. The claims that the email SRA2 and subsequent letter SRA3 were confidential were equally false. The content of the email and letter lacked the quality of confidence (as all the information in the documents was already public or obvious). There was nothing in our relationship which suggested that a duty of confidence could be imputed to me – the letter was unsolicited. Even if the letter had contained confidential information, there was a clear public interest in the matters under discussion (which would override the duty of confidence).

13. Hence the claims that the email was “without prejudice” and the email and letter were “confidential” were without merit, an attempt to mislead, and a breach of the SRA Principles.

Aggressive and intimidating threats

14. The email asserts that the “without prejudice” rule prevents me from publishing or even referring to the letter. This is entirely false. It is often tactically unwise for a party to publish without prejudice correspondence, but the “without prejudice” rule is a rule of evidence and does not prevent publication. This was, again, false, and an attempt to mislead. However, it is more serious than that: it is an aggressive and intimidating threat (“That would be a serious matter as you know.”).

15. The second Osborne Clarke communication, SRA3, also seeks to intimidate me into not publishing the letter. It asserts that doing so would be “improper” (paragraph 1.3) but does not give a legal rationale for this claim – most likely because there is no such rationale.

Advancing meritless claims – false allegations

16. As you identify in your warning notice, a common characteristic of SLAPP pre-action correspondence is that it advances meritless legal claims.

17. The entirety of the first Osborne Clarke email (SRA2) is meritless. The central allegation is:

“You have relied on comments attributed to YouGov by The Times today to support your view that our client was lying about the extent of involvement of our client’s father in the very early days of YouGov when it was set up in 2000.”

18. This misrepresents the comments I had made. I had specifically alleged that Mr Zahawi lied when he claimed that his father provided startup capital to YouGov (his first explanation). I did not allege that Mr Zahawi’s subsequent explanation was a lie (the second explanation – that Balshore Investments acquired its shareholding because Mr Zahawi’s father was so involved in the running of the business).

19. It is hard to imagine a more meritless defamation action than complaining about an allegation that was not in fact made.

20. The Osborne Clarke email (SRA2) at no point attempts to respond to my actual allegation. The closest it comes is by saying I omitted to reference that Mr Zahawi’s father paid £7,000 for his second tranche of shares. But I clearly did mention this, in both my Twitter thread (https://taxpolicy.org.uk/evidence) and my longer article (https://taxpolicy.org.uk/zahawi-capital/). The lack of attention Osborne Clarke paid to the facts evidences recklessness and/or a lack of interest in the merits of the case, both of which are identified in the SRA “conduct in disputes” guidance as unacceptable behaviour.

Advancing meritless claims – no legal basis

21. Your risk warning specifically mentions cases where a solicitor pursues a claim despite knowing that a legal defence to their claim will be successful.

22. At the time, Nadhim Zahawi was Chancellor of the Exchequer. It is hard to imagine a topic of higher public interest than an accusation that the Chancellor of the Exchequer had avoided tax and lied about it. Hence Osborne Clarke would have known that a public interest defence under section 4 of the Defamation Act 2013 would likely have been successful. It is notable that their communications do not mention the public interest defence.

Advancing false factual claims

23. Another common element of SLAPP pre-action letters is for the solicitor to advance factual claims by their client which are false, and which the solicitor should know are likely false. As your guidance notes, solicitors should take reasonable steps to satisfy themselves that a claim is properly arguable before putting it forward.

24. In this instance, both Osborne Clarke communications (SRA2 and SRA3) assert that Balshore provided £7,000 of startup capital for the YouGov shares it acquired in 2000. See, for example, paragraph 2.4 of SRA3.

25. However, the Companies House form for the share issuance shows that it was signed in October 2002, but backdated to 2000 (see attachment SRA8). My review of YouGov’s accounts and other Companies House filings confirm that the £7,000 was paid in 2002, not 2000 (I can supply evidence of this if that would be helpful).

26. Hence the key factual component of the Osborne Clarke letters was false. Osborne Clarke cannot have made any attempt to verify the matter (given that a cursory review of the Companies House form would have immediately revealed the backdating).

27. There is no duty on a solicitor to conduct detailed due diligence to fully investigate a client’s factual assertions. However, where the solicitor is going to assert factual matters in a letter to a third party, as a central part of a threatened claim against the third party, the solicitor should have some proper basis for doing so. The solicitor’s duty to the third party and the rule of law mean that the solicitor cannot simply advance any factual assertion made by his or her client, without the slightest investigation. A solicitor is not a mere post-box, particularly when serious allegations of defamation are being made. The failure of Osborne Clarke to make any checks on the claim was reckless and a breach of the SRA Principles.

28. The breach subsequently became more serious. I drew Osborne Clarke’s attention to the falsehood of the £7,000 claim, but (now knowing it was likely false) they did not correct the record. At that point Osborne Clarke became complicit in misleading me. I discuss this further below.

No intention of actually commencing litigation

29. A further common characteristic of SLAPPs (mentioned in your guidance) is where a solicitor is acting in a public relations capacity, with a legal veneer but no actual legal content. One example of this is where a solicitor makes a threat of a defamation lawsuit which is a “bluff”. The solicitor and client have no intention of filing an actual defamation claim, either because the client’s case is too weak (for example because the honest opinion or public interest defences will apply), or because the claimant would not want to run the risk of pre-trial disclosure or cross-examination during trial. The solicitor therefore engages in purported pre-action correspondence with the aim of intimidating the recipient into withdrawing their accusation. This is abusive behaviour, damaging to the rule of law. When combined with mislabelling, the overall effect is that people are silenced, with no way for the public or the judicial system to ever know about it.

30. It will often be hard to judge whether a solicitor’s correspondence falls within this category. This, however, is an unusual case where we can be confident that it does. The key sentence in Osborne Clarke’s email (SRA2) reads:

“Should you not retract your allegation of lies today, we will write to you more fully on an open basis on Monday.”

31. The natural reading of this is that, if I did not retract, Osborne Clarke would send me a pre-action letter, with a view to subsequently commencing defamation proceedings. However when I did not retract, I did not receive a pre-action letter. Osborne Clarke’s subsequent letter (SRA3) is explicit that it is “not a threat to sue for libel”. And when I still did not retract, I received no further correspondence (and no libel claim has been forthcoming).

32. Hence, the evidence suggests that Osborne Clarke was bluffing: this was pre-action correspondence as an end itself – a SLAPP, and a breach of the SRA Principles. It was, perhaps, not pre-action correspondence at all – but Osborne Clarke acting in a “reputation management”/“public relations” capacity of the kind that your 28 November warning identifies.

33. It may be that, if you review Osborne Clarke’s files, you will find that Mr Zahawi had told Osborne Clarke he had no intention of commencing proceedings.

Reason for writing

34. I had not intended to make a formal complaint about Osborne Clarke. However, their behaviour since I called their “bluff” has evidenced a serious misunderstanding of a solicitor’s professional duties and obligations:

35. I wrote to Osborne Clarke on 19 August 2022 (attachment SRA4) alerting them to the fact that their central claim about the £7,000 was false, and inviting them to correct the record.

36. Their response on 25 August 2022 did not address the point (attachment SRA5).

37. I responded on 31 August 2022 (attachment SRA6) making clear that I expected Osborne Clarke to address the three falsehoods in their correspondence: the false claim Balshore had provided £7,000 of capital, the false claim of confidentiality, and the false claim that the “without prejudice” rule prevented publication. I invited them to justify or withdraw their claims, and pointed out that it was not open to a solicitor to make a false statement and, knowing it was likely false, fail to correct it. Whilst Osborne Clarke may originally have made a mistake, or been reckless, in presenting the false £7,000 claim, at the point they realised it was likely false, and failed to correct the record, they became complicit in misleading me.

38. Osborne Clarke responded on 8 September (attachment SRA7). On my first point (the £7,000 of capital), Osborne Clarke simply said that their professional conduct rules prohibit them from discussing client confidential matters. This is a non-sequitur. If the solicitor becomes aware that he or she has (intentionally or unintentionally) misled a third party then the solicitor must correct the record – otherwise the failure to correct is itself a breach of the SRA Principles. Client confidentiality will in most cases not prevent such a correction (the duty of confidence will not apply if the solicitor is being asked to perpetrate a falsehood). But if there is a conflict then client confidentiality does not simply override other SRA Principles; the solicitor is then faced with a serious ethical dilemma which the solicitor may only be able to resolve by ceasing to act for the client. Osborne’s Clarke’s response was unacceptable.

39. On my second point (the false assertions of confidentiality and without prejudice), Osborne Clarke said that they would address their responses to the SRA. Again, this is a non-sequitur. A solicitor’s duty not to mislead a third party is not owed to the SRA; it is owed to the third party.

40. I had hoped Osborne Clarke would correct the record of their own accord, and I would not need to refer the matter to you. Unfortunately, it is clear they will not do so – it is for that reason I have written this letter.

Wider implications

41. It is my understanding that the key features of Osborne Clarke’s correspondence are commonplace: false assertions of confidentiality and “without prejudice”; an attempt to intimidate the recipient into not publishing the letter; basing a libel threat on a client’s assertion of facts without any attempt to very if those facts are correct.

42. I would, therefore, ask you to review other defamation matters where Osborne Clarke was instructed, to ascertain if they have indeed breached the SRA Principles on other occasions (it may be that this is already underway as part of your thematic review into SLAPP).

43. You will appreciate that I was a very atypical recipient: as a former partner in a large law firm I had the legal knowledge to identify that the claims being made were false, the contacts to obtain expert advice, and the financial resources to pay for that advice. Osborne Clarke’s actions caused me to incur unnecessary legal fees, but had no other adverse consequences and I was not, in the end, silenced.

44. I expect many other recipients of these letters did not have those advantages, and were silenced by meritless claims of confidentiality. The damage to the profession and the rule of law can only be undone if these letters can be identified, and Osborne Clarke and/or the SRA then writes to the recipients making clear that the confidentiality assertions were false. Whether Osborne Clarke’s client permits them to do so is irrelevant: a solicitor’s public interest obligations override their duty to their client.

45. If there is indeed a pattern of behaviour of Osborne Clarke falsely labelling as confidential/without prejudice letters to unrepresented parties, making meritless claims, and making false assertions of facts, then I would ask that you bring Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal proceedings against Osborne Clarke, and seek the most serious sanctions against those involved.

46. Do please let me know if I can be of any further assistance. I would ask that you contact me by email rather than by post.

Yours sincerely

Dan Neidle

Photo of Nadhim Zahawi by Richard Townsend