Companies House’s rules were created in an era of trust, where incorporating a company took time and expertise. Automation made incorporating a company much faster and easier – but the rules didn’t change. That means Companies House ends up facilitating large-scale frauds.

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill introduces ID verification requirements, and creates a new investigative and enforcement role for Companies House. Much will depend on how Companies House adapts to that new role. But there are also key vulnerabilities that the Bill does not remove: the “false registered office” fraud, the “dissolve within a year” loophole and the “muppet director” fraud.

Companies House is just a robot

Blaming Companies House for its failings is like blaming a traffic light for turning red. It’s just following its programming.

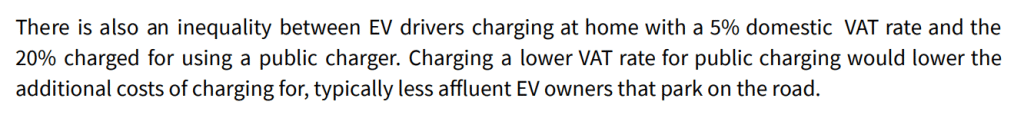

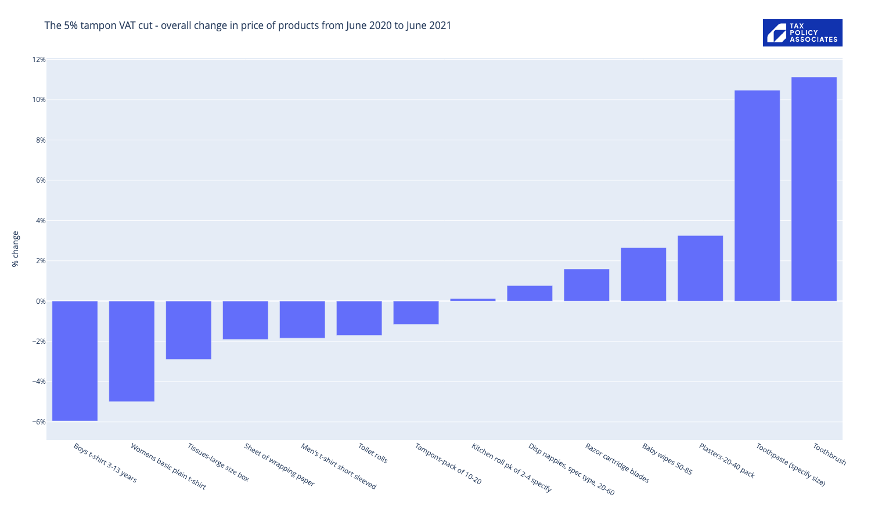

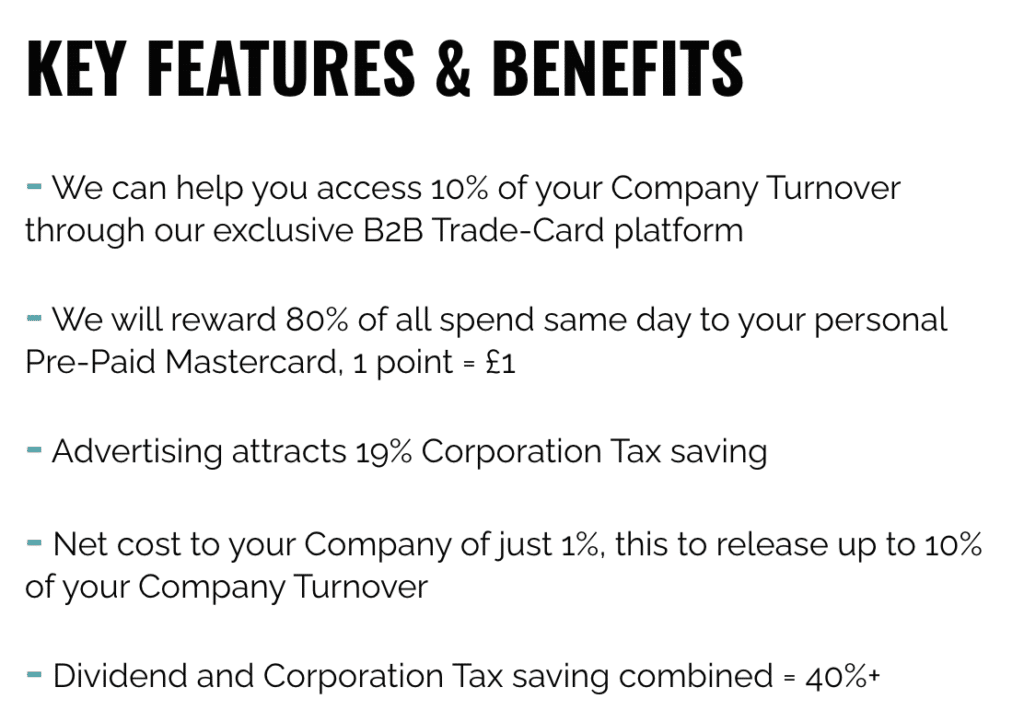

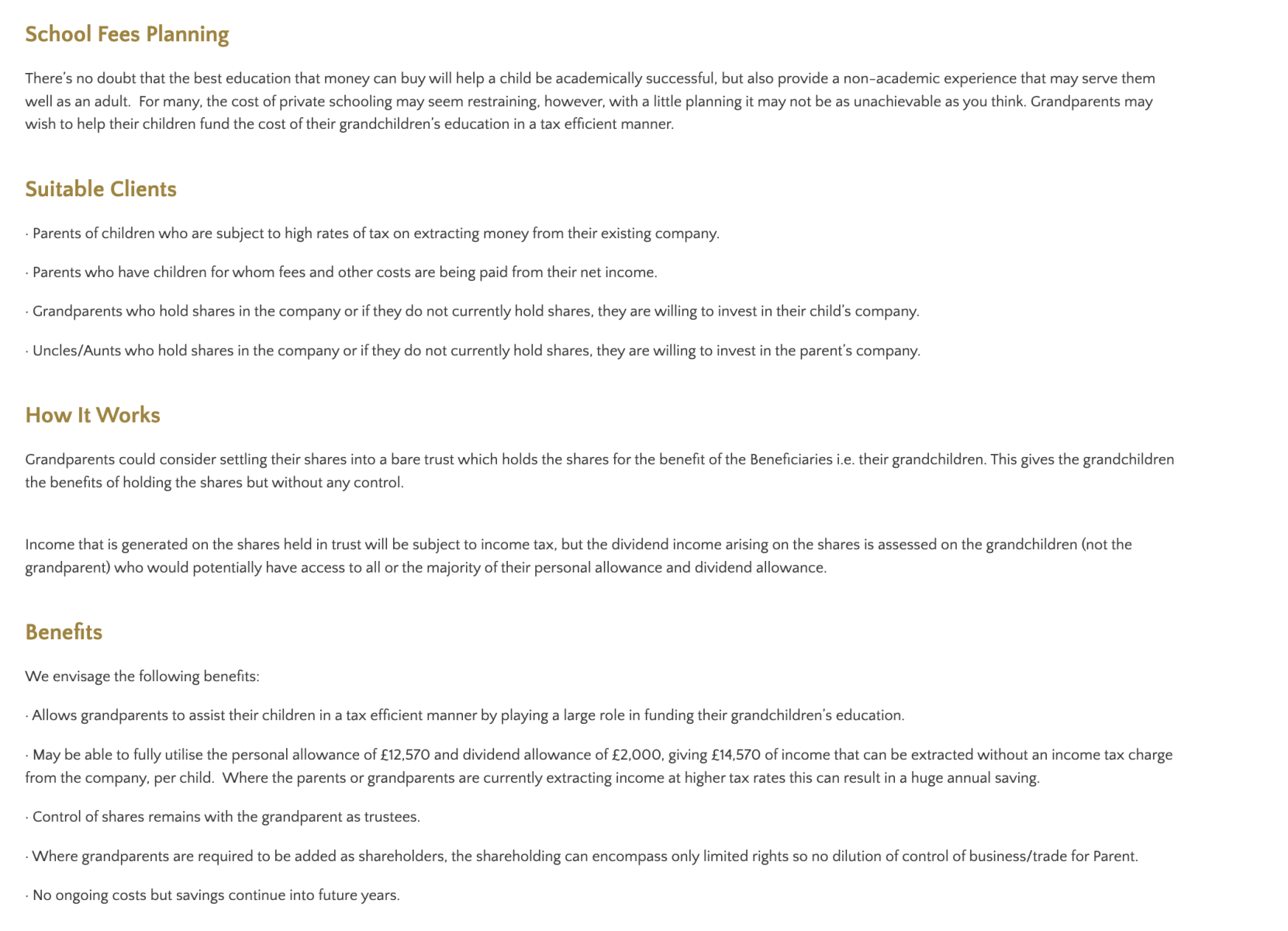

The programming is in the Companies Act 2006 – here’s the key section stating what you have to provide to create a company:

![9Registration documents

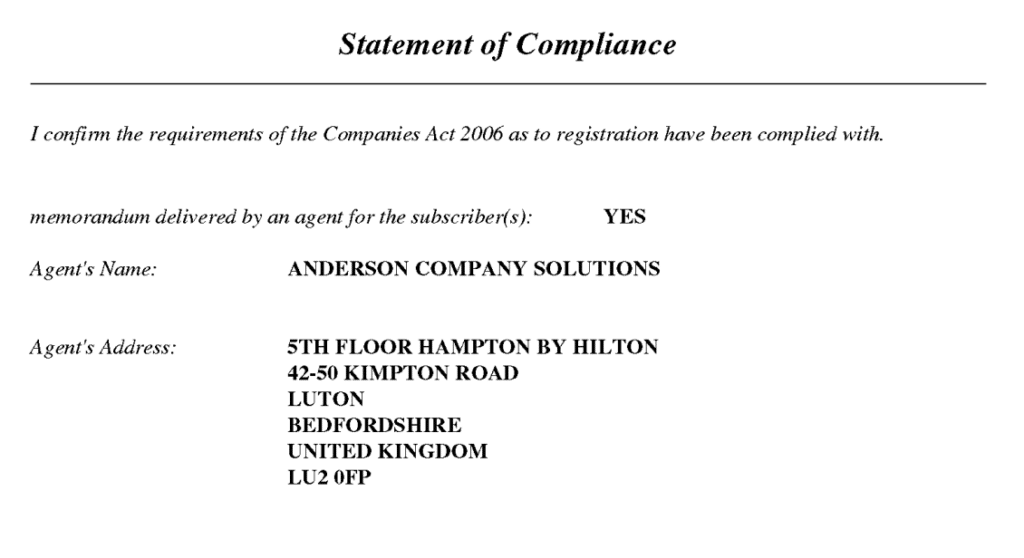

(1)The memorandum of association must be delivered to the registrar together with an application for registration of the company, the documents required by this section and a statement of compliance.

(2)The application for registration must state—

(a)the company's proposed name,

(b)whether the company's registered office is to be situated in England and Wales (or in Wales), in Scotland or in Northern Ireland,

(c)whether the liability of the members of the company is to be limited, and if so whether it is to be limited by shares or by guarantee, and

(d)whether the company is to be a private or a public company.

(3)If the application is delivered by a person as agent for the subscribers to the memorandum of association, it must state his name and address.

(4)The application must contain—

(a)in the case of a company that is to have a share capital, a statement of capital and initial shareholdings (see section 10);

(b)in the case of a company that is to be limited by guarantee, a statement of guarantee (see section 11);

(c)a statement of the company's proposed officers (see section 12)[F1;

(d)a statement of initial significant control (see section 12A).]

(5)The application must also contain—

(a)a statement of the intended address of the company's registered office; F2...

(b)a copy of any proposed articles of association (to the extent that these are not supplied by the default application of model articles: see section 20)[F3; and

(c)a statement of the type of company it is to be and its intended principal business activities.]

[F4(5A)The information as to the company's type must be given by reference to the classification scheme prescribed for the purposes of this section.

(5B)The information as to the company's intended principal business activities may be given by reference to one or more categories of any prescribed system of classifying business activities.]

(6)The application must be delivered—

(a)to the registrar of companies for England and Wales, if the registered office of the company is to be situated in England and Wales (or in Wales);

(b)to the registrar of companies for Scotland, if the registered office of the company is to be situated in Scotland;

(c)to the registrar of companies for Northern Ireland, if the registered office of the company is to be situated in Northern Ireland.](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Screenshot-2023-07-10-at-10.08.49-1024x964.png)

Note what’s missing here: any requirement to prove identity, or prove that the company actually owns the registered office address (or has the right to use it). Compare, for example, with the information banks require before you can open a bank account.

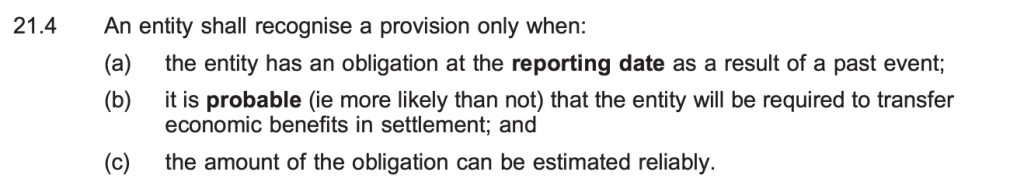

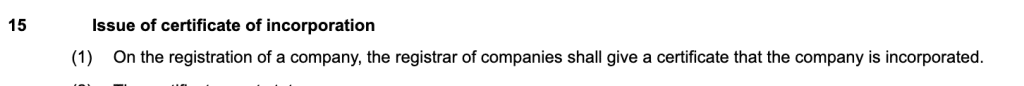

And, once someone has complied with the registration requirements, Companies House is required to accept them:

And then required to incorporate the company:

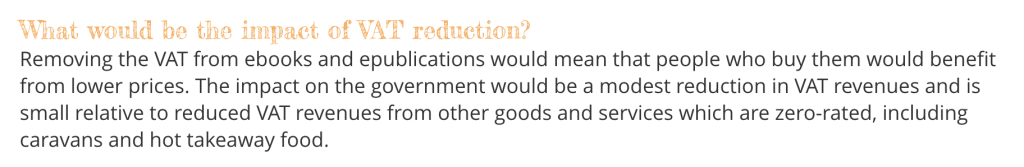

The obvious missing piece: any requirement on Companies House to follow anti-money laundering procedures. Here’s 118 pages of guidance on how financial institutions are expected to prevent, identify, and report financial crime. Banks, law firms, estate agencies… all kinds of businesses are expected to comply with AML rules. Companies House isn’t.

Nor can Companies House voluntarily comply with AML rules, make sensible checks, or say “this doesn’t feel right” and refuse registration. The word “shall” in sections 14 and 15 above means that Companies House is a robot – if it receives the registration information, it creates the company.

Companies House has worked this way pretty much unchanged since 1856 – behaving like a robot, incorporating companies without asking any questions. That more-or-less worked when incorporating companies was reasonably slow and complicated – there were certainly frauds, but the numbers were limited, which made it easier for authorities to track what was going on.

The big change was automation, and the decision in 2001 to allow online filing… but without changing any of the rules. That suddenly enabled very large-scale fraud.

The consequences

Here are just six:

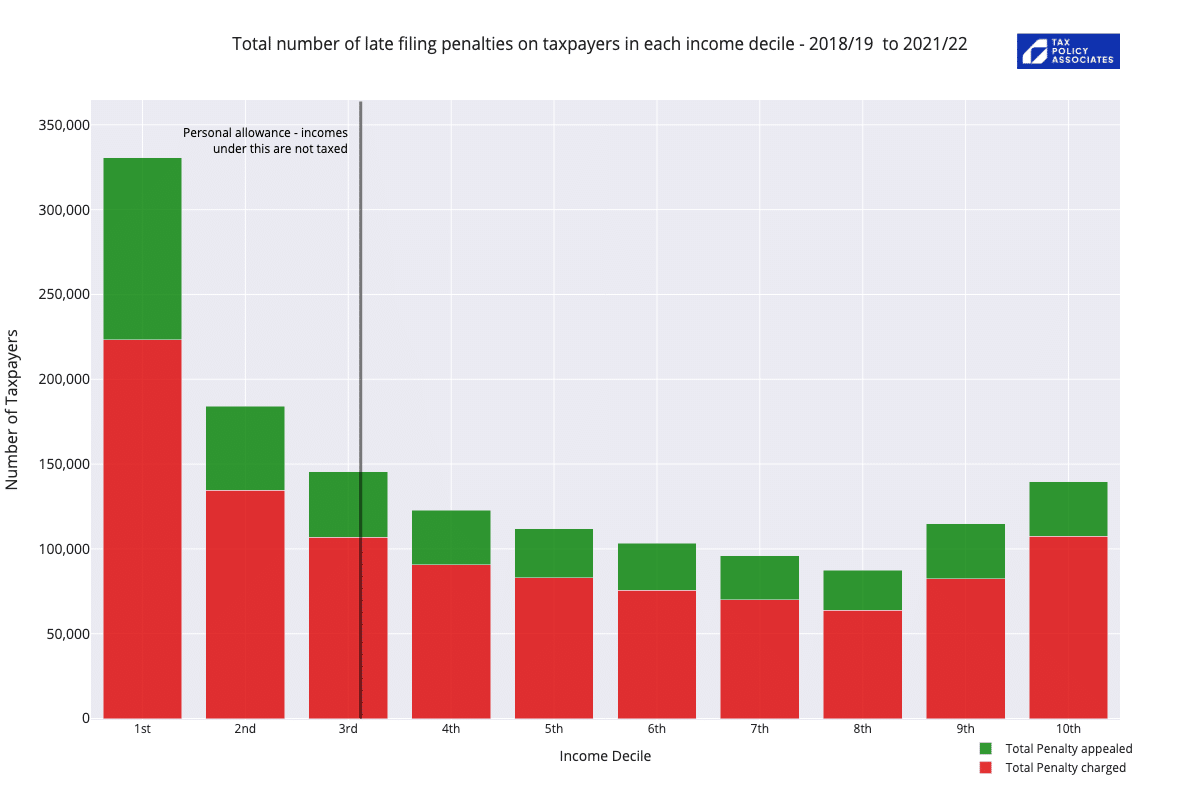

1. Suspicious behaviour isn’t noticed or acted on

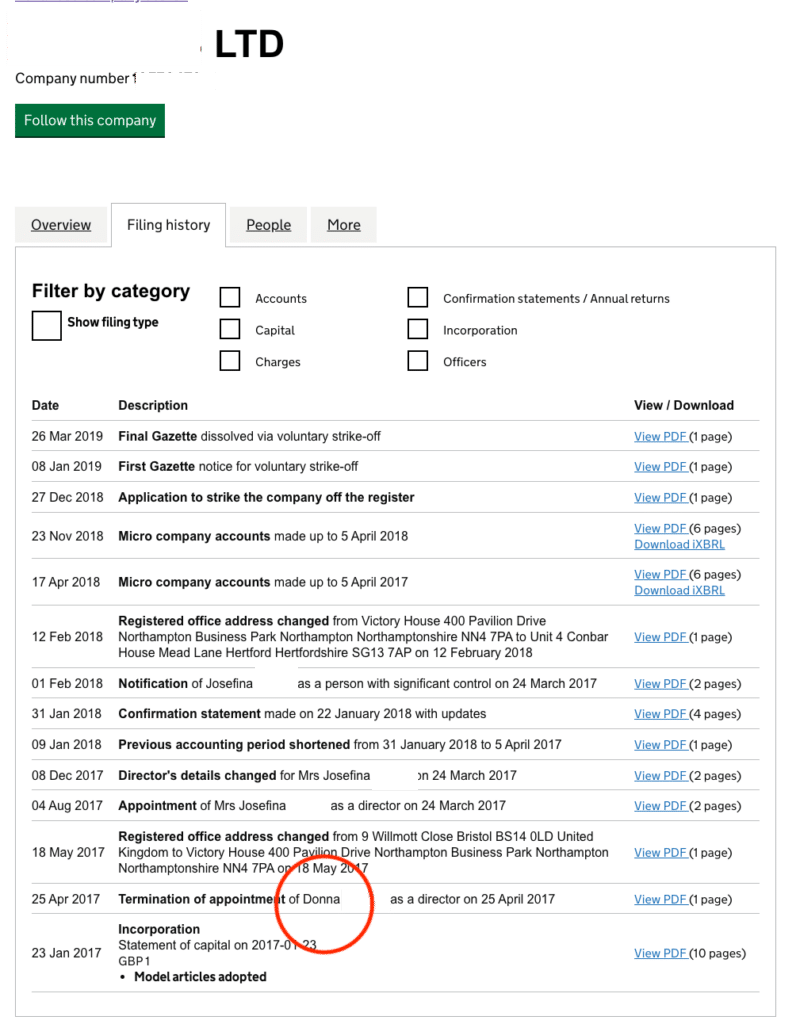

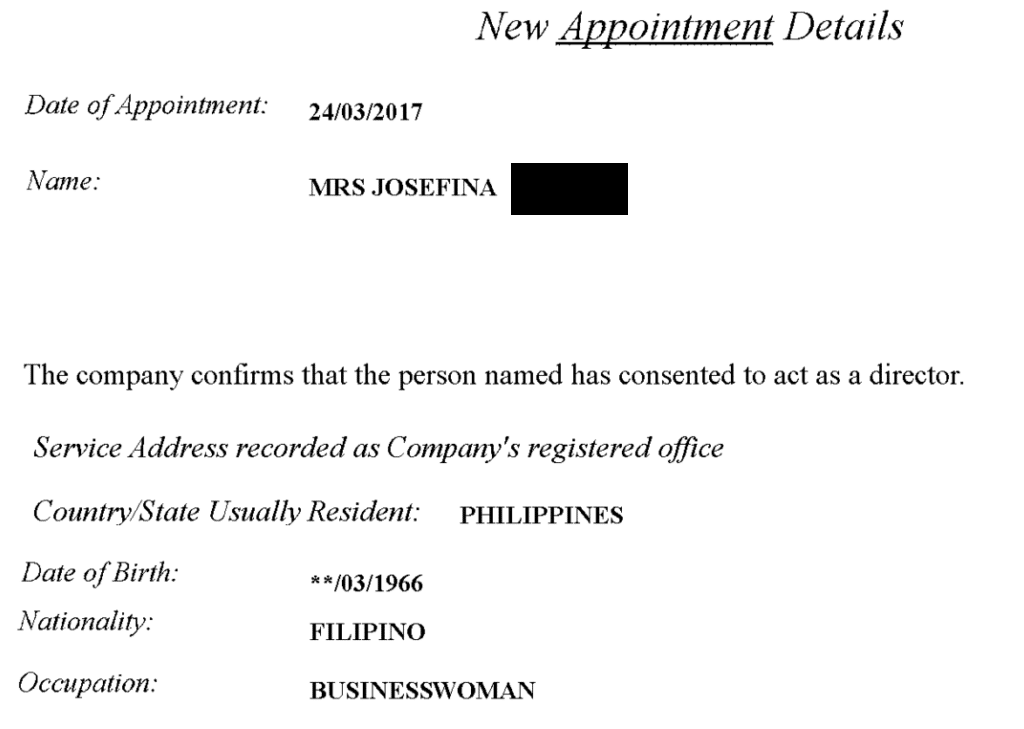

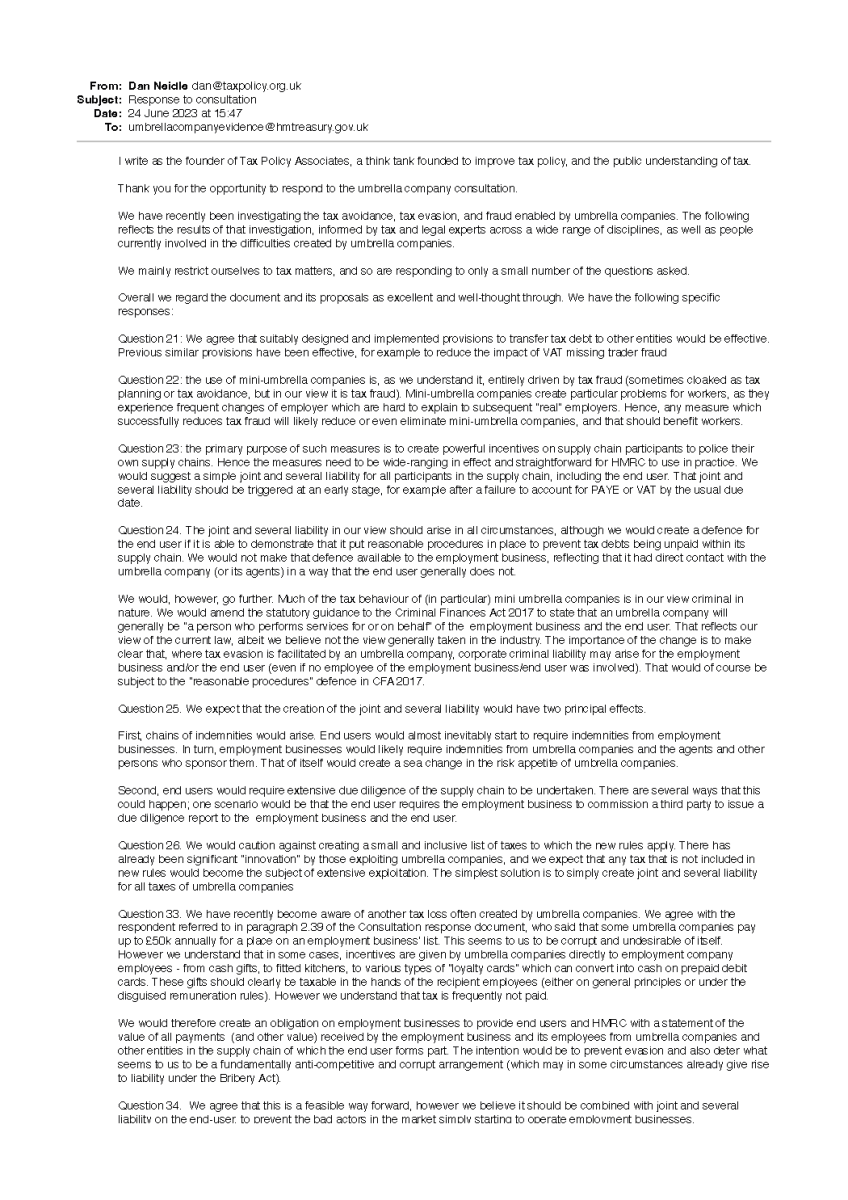

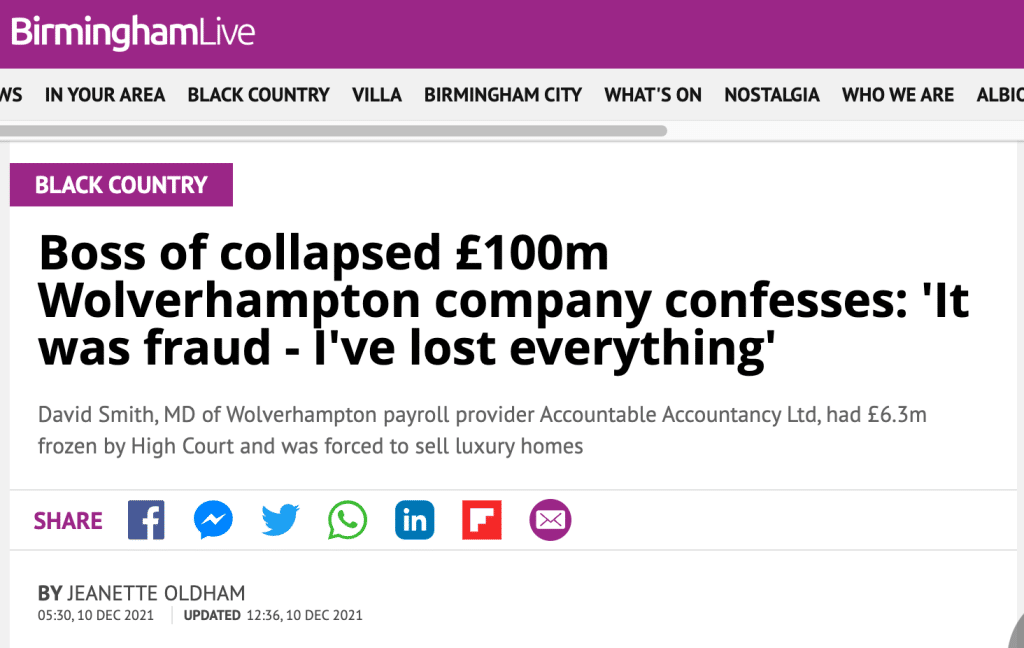

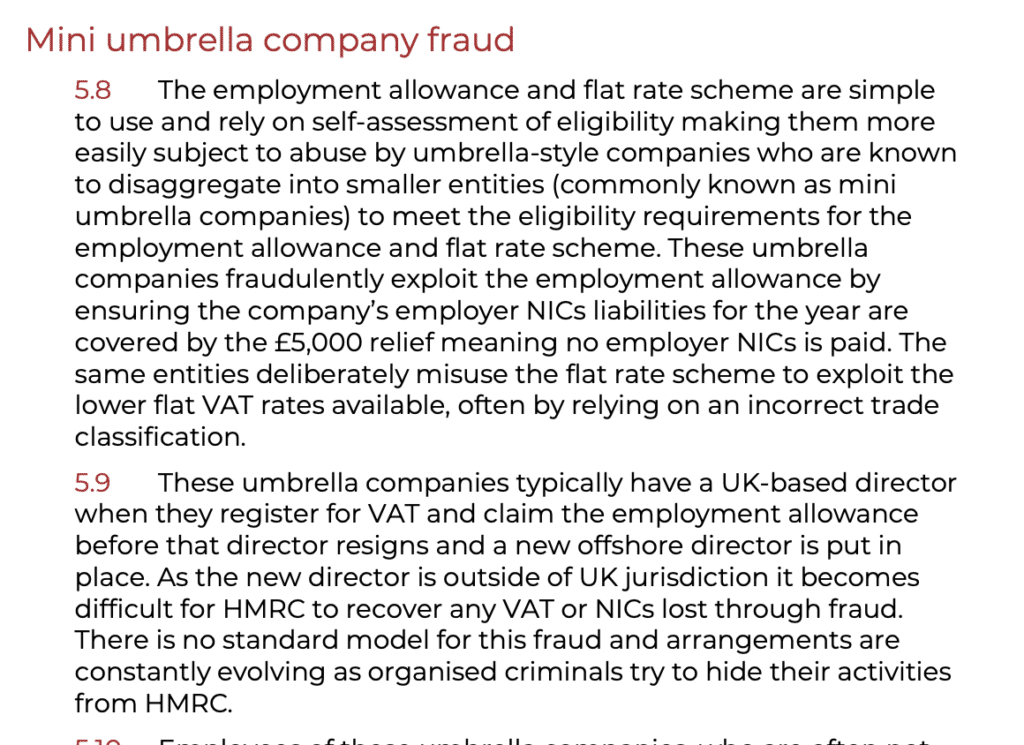

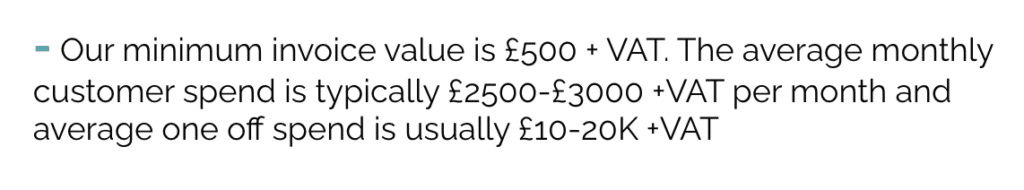

In 2017, thousands of UK companies were set up overnight with Philippine directors, all registered to UK addresses. The resultant “mini-umbrella company” fraud cost the UK at least £50m in lost tax, and the many MUCs that followed could have cost £1bn.

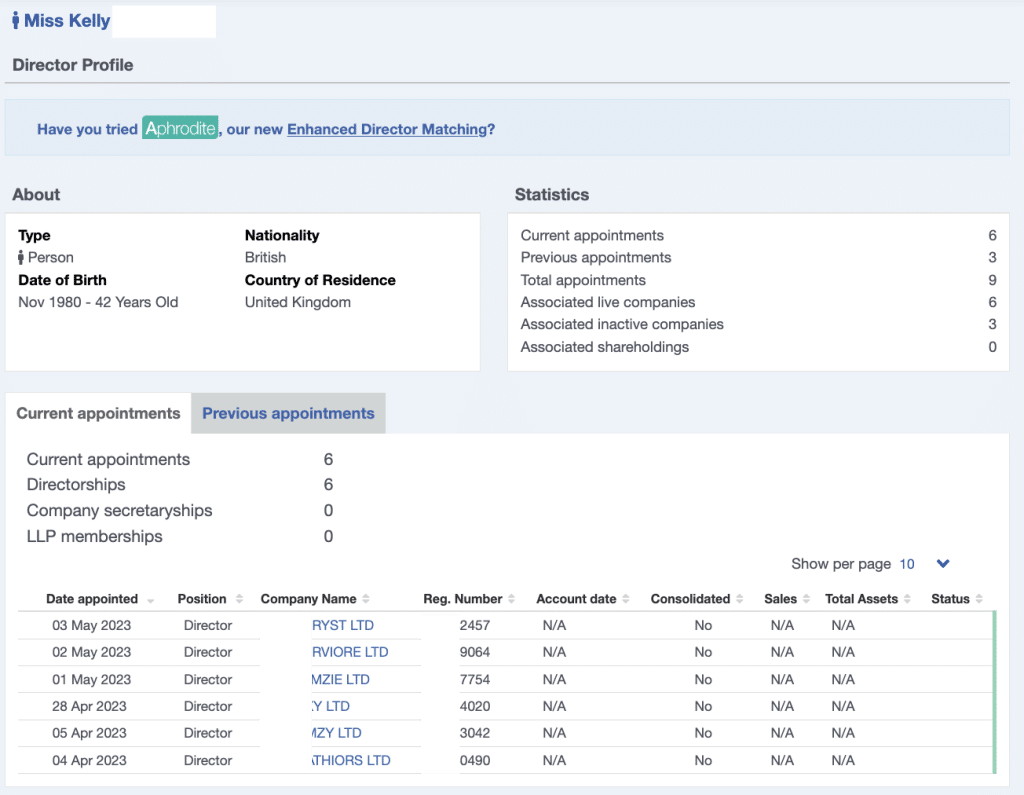

The exact same fraud continues. Just last Thursday, 74 new companies were simultaneously put into ownership of Filipino directors:

These are, in principle, completely lawful transactions. There’s nothing wrong with setting up a company with a Filipino director, or appointing a Filipino director to an existing company. Doing so en masse is, however, extremely suspicious. A bank would which didn’t flag and query (or report) these kinds of transactions would be in deep trouble. But Companies House has no procedures for identifying suspicious behaviour.

2. Companies House believes everything it’s told

You can submit literally almost anything to Companies House and it will accept it.

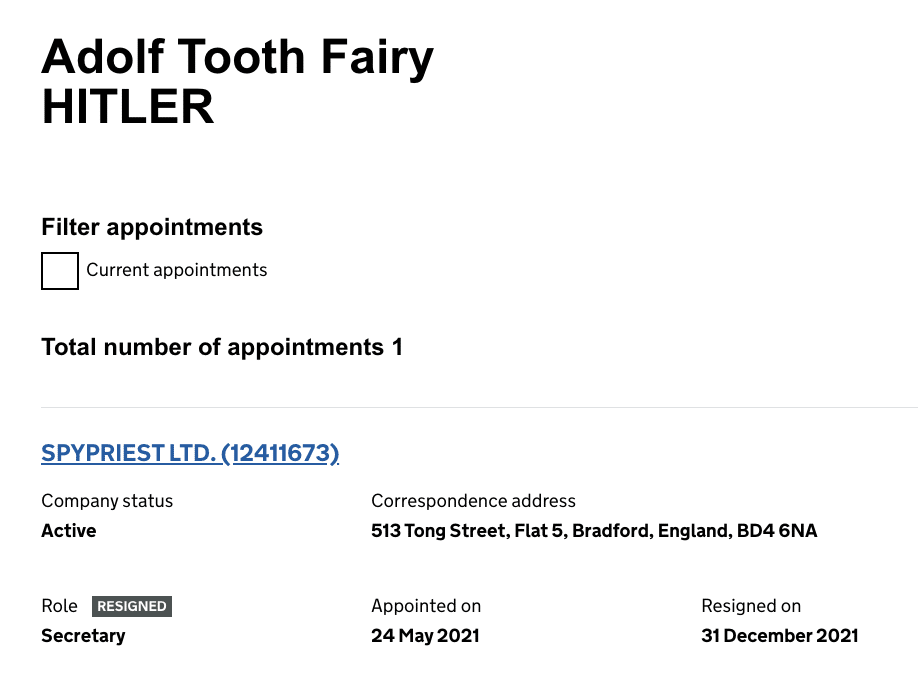

A fake name for a director (surely a joke):

A fake registered office (surely a fraud):

and:

Even less of a joke, Graham Barrow has shown that a UK company with a fake address was used by North Korea to breach sanctions.

These are not isolated incidents. 10,000 people had to apply to Companies House last year to fix companies being wrongly (probably meaning fraudulently) registered at their home and businesses addresses. Likely there are many more that aren’t noticed.

All of these have the same cause: there is no checking of your ID when you incorporate a company, or become a director. And no checking that the registered office address is in fact yours.

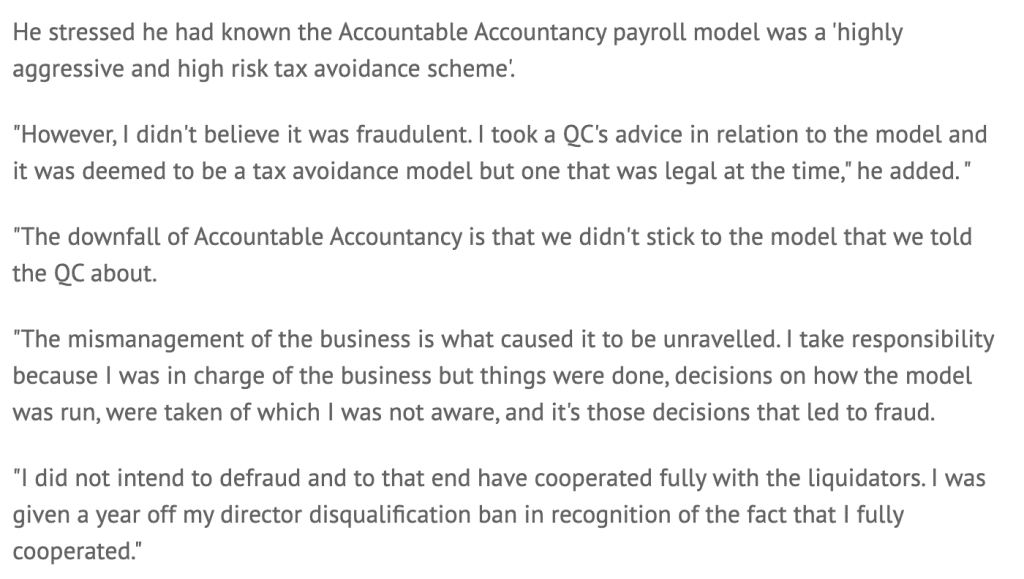

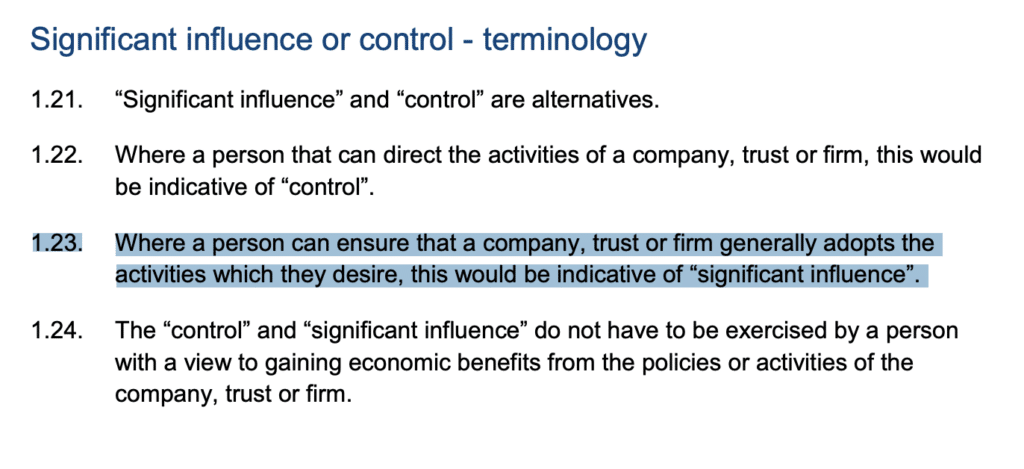

3. The optionality of the PSC register

Companies are supposed to identify the actual humans who control them – the “people with significant control”. But the rules are widely ignored, and there appears to be no enforcement.1

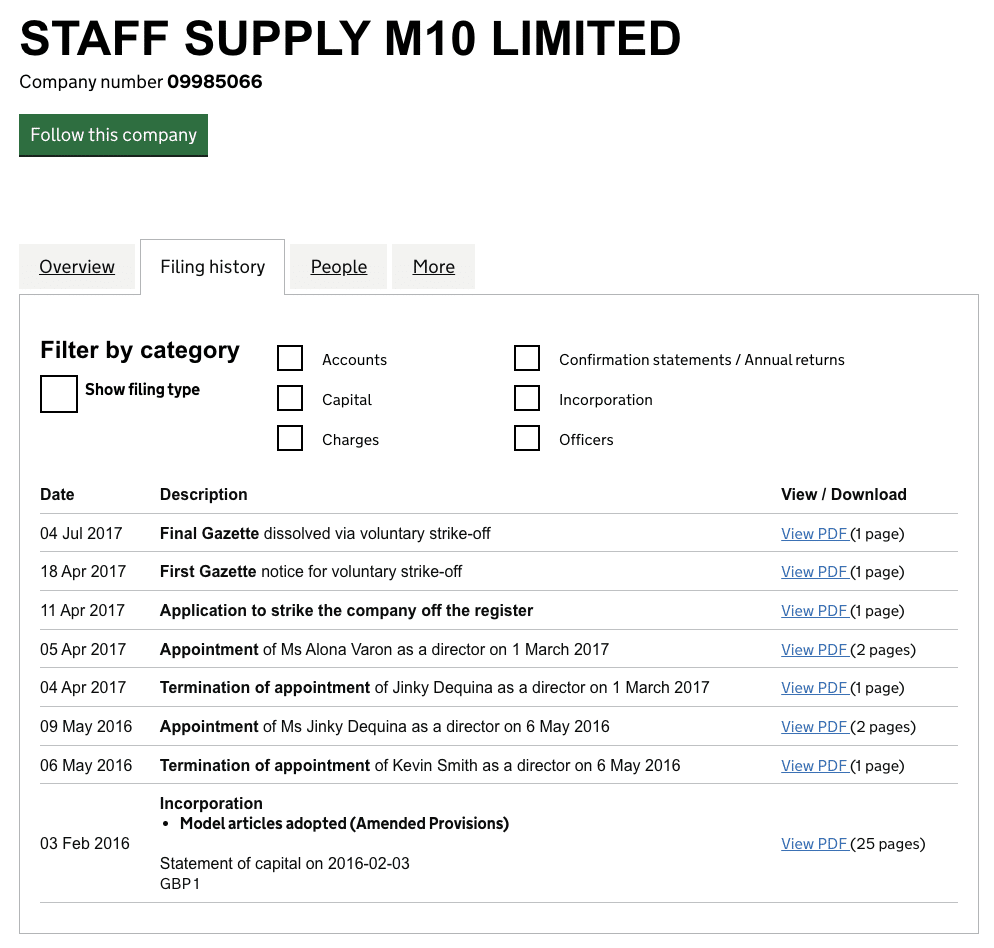

4. The “dissolve within a year” loophole

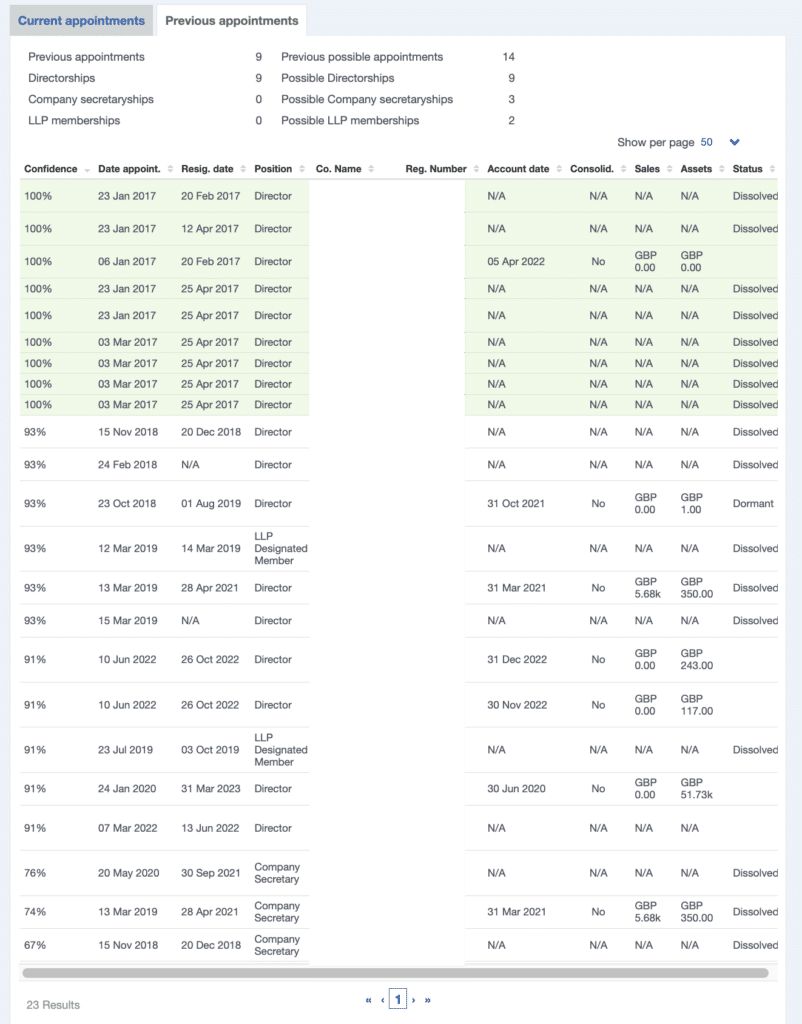

You don’t have to file any accounts if you dissolve a company within a year of creating it. It’s a loophole that fraudsters exploit at a large scale. Tens of thousands of mini-umbrella companies use it every year. Here’s a typical example:

5. The accounts opt-out

Companies filing accounts at Companies House usually have to include their profit and loss account, with details of revenues and expenses for the year. However, “micro-entities” – broadly meaning companies with revenues of less than £10m – can opt out of this:

Instead, they can just file what are sometimes called “filleted accounts”, containing only basic balance sheet information. That’s fantastic for anyone looking to hide what they’re up to.

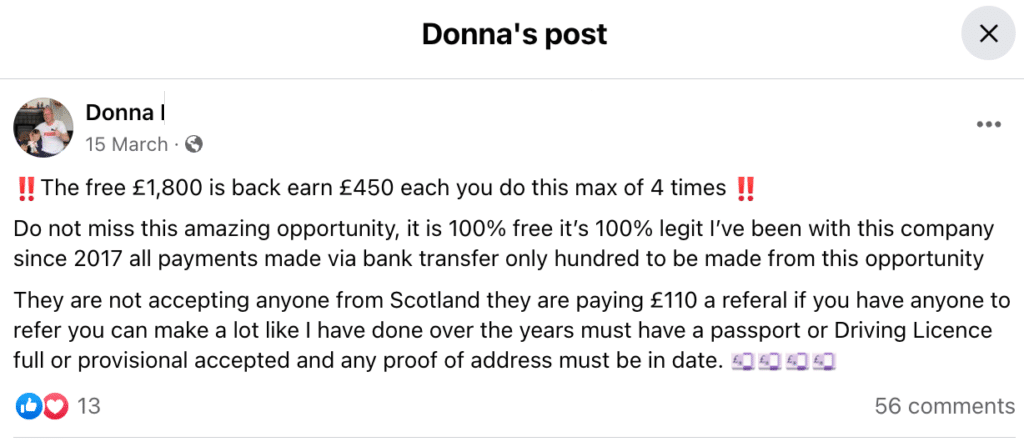

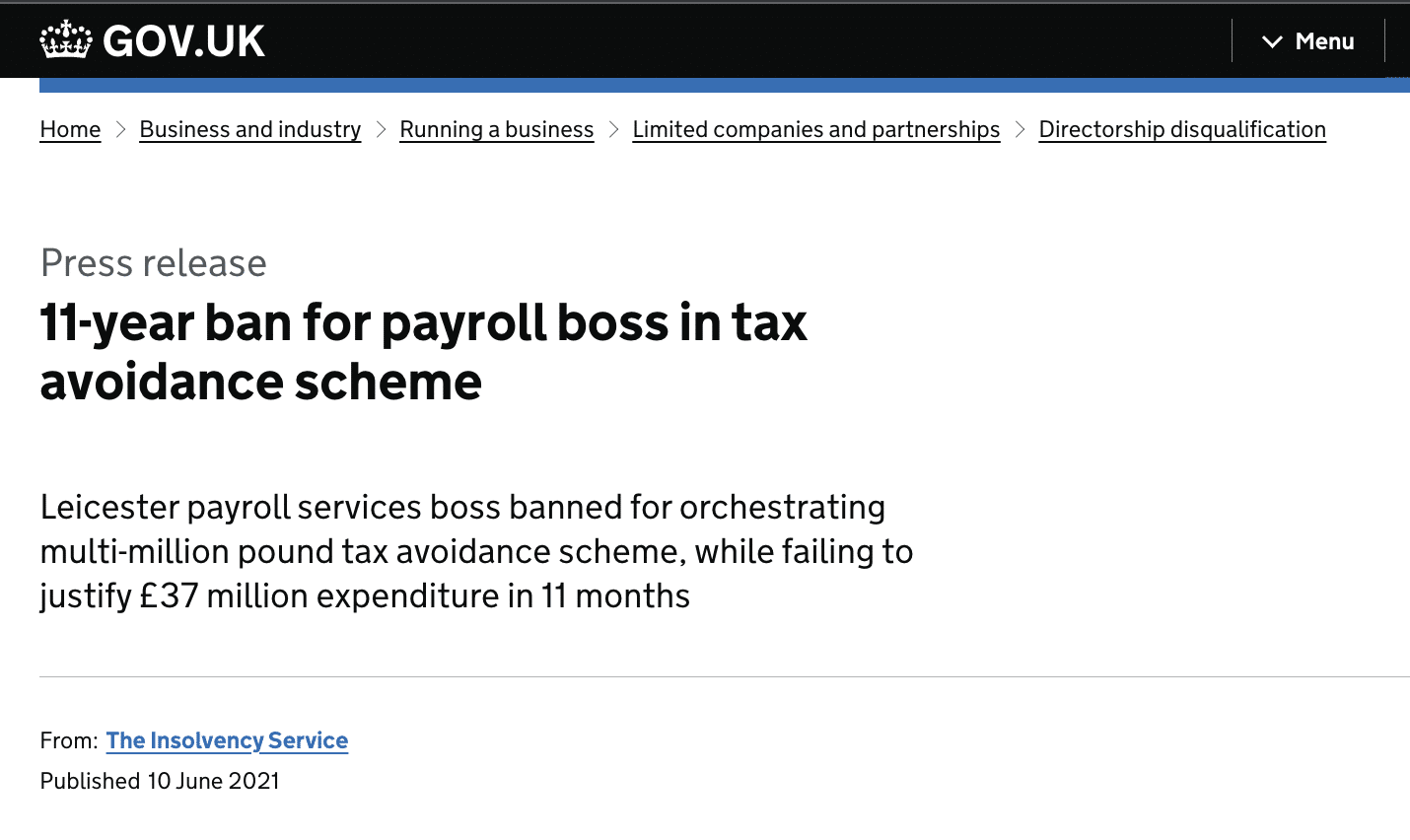

6. The muppet director fraud

Being a director of a company is a serious role, with fiduciary duties and potential liability if things go wrong. You are also immediately associated with the company in a permanent public record.

These are bad things if you’re running a fraud, or expect the company to go bust with unpaid debts and/or unpaid tax. As the director, those debts could transfer to you.

So the obvious move is to not be a director at all, but be a puppeteer for a bunch of muppet2 “nominee directors” who you hire off social media, either in the Philippines…

… or in the UK:

It’s a fraud because it relies upon concealment: if everybody discovers what’s going on, it doesn’t work. There’s no such thing as a “nominee director” as a matter of UK company law. A puppeteer will be a “shadow director”, just as liable as a real director. The muppet director strategy is a fraud from start to finish.

But it’s an easy fraud, because there’s no shortage of people willing to sign up as a director for a few hundred quid, and Companies House realistically has no way to know if a director is real, or a muppet.

The new Bill

All these problems have been written about for some time – nothing above is new or original. There is, however, finally some action – a host of new measures in the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill. That will end some of the frauds and loopholes, but not others.

Stopping the robot

Probably the most important element in the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill are a host of new powers for Companies House to require information from companies, modify company information at its discretion if it thinks it’s incorrect, and ultimately even strike off companies if false information was provided to Companies House:

This is a big change – Companies House is no longer a robot.

But will Companies House have the resources to use its shiny new powers? The Autumn 2021 Spending Review pledged £63m:

The SR21 period is 2022/23 to 2024/25 – so this is about £20m per year. Presumably that’s enough to establish the new ID verification systems. However it’s not intended to cover ongoing running costs – Companies House is supposed to be self-funded, by means of the incorporation and other fees it charges companies. Currently, online incorporation costs a rather derisory £12. Companies House has dropped unsubtle hints this will be going up.

How high should it go? UK Finance suggested £50 to £100; but there’s a good argument that incorporating a company should be more expensive. Back in 1990, it cost £50 to incorporate – that’s £120 in today’s money. When online incorporation was created, the costs for Companies House were greatly reduced, and so fees were cut commensurately. That looks like a mistake in retrospect – no genuine business would be deterred by a £120 fee, but it would damage the economics of some large-scale frauds. So we should consider ending the principle that the only purpose of Companies House fees is to fund Companies House.

In any case, it’s plausible that a £120 fee would be the right amount to create an effective and proactive compliance and enforcement team. It would raise around £60m per year,3 which doesn’t feel excessive. For context, UK financial institutions report an average annual anti-money laundering and compliance cost of £186m (that’s per financial institution, not the sector overall), and these are now very mature systems. Companies House would be starting from scratch.

Stopping Adolf Tooth Fairy Hitler

The Bill includes an identify verification requirement for incorporation and all delivery of documents to Companies House:

Over the twelve months after the Bill comes into force, as each company files its annual confirmation and accounts, every company will have at least one person whose identity has been confirmed. That should end Adolf Tooth Fairy Hitler.

Stopping proper accounts being optional

The very limited accounts filing requirements for micro-entities are finally being tightened. The Economic Crime and Transparency Bill requires all companies to file a profit and loss account.

But nothing to stop Cardiff flat owners receiving 11,000 tax bill

So far as I can see, the ID verification requirements won’t stop the “fake registered office” frauds.

Provided I verify that I am Dan Neidle, nothing stops me from putting a random Cardiff address as my registered office address. That would be a foolish thing for me to do, as (in theory) I could easily be found and prosecuted. But prosecution is going to be little deterrent for people on the other side of the world.

How could registered office be verified?

- Usual KYC checks involve e.g. a bank statement addressed to that office. But a company that is about to be incorporated will, by definition, not have any bills addressed to it.

- A direct legal connection between a director and the proposed address; for example the director being registered as the owner of the real estate. Will often not be the case.

- Authorisation by the legal owner of the real estate that the new company can use the address as its registered office. The authorisation would be via the Companies House portal for the company owning the real estate. In principle That would require building a system that links Companies House and the land registry; given the complexity of land titles this may not be a straighforward task.

- Or a simple fallback: Companies House send an automated letter to the registered office address, including an authorisation code, and requiring that the authorisation code be entered before incorporation can proceed. That’s how HMRC secures registration for self assessment – it’s not obvious why incorporating a company should be easier.

Nothing to close the “dissolve within a year” loophole

I’m not aware of any plan to require companies to file accounts before they dissolve. That will continue to make UK companies attractive for people trying to hide their tracks.

Nothing to end “muppet” directors

To be fair, it’s not clear how this could be done.

The splendid automation of Companies House procedures, and the fact there are lots of people happy to receive a few hundred quid for clicking buttons, means it’s hard to identify or stop “muppet” directors.

It may be worth considering a “nudge” – a page on the Companies House website, which new directors have to click through, warning them that, if they’ve been asked to become a director of a company by people they don’t know, then it could be a scam, or it could involve them in organised crime, and could result in liability for unpaid tax etc, or even criminal prosecution. How effective would such a “nudge” be? I don’t know. But it may be worth trying.

Almost nothing in this report is original; it draws on research by Graham Barrow and others.

Image: Stable Diffusion “giant looming over a pile of money” (thanks to my nine-year-old)

Footnotes

There’s a procedure for people at an AML-regulated firm to report discrepancies in PSC data (although it’s not clear if that is ever acted on), but no procedure for the rest of us. ↩︎

I didn’t invent the term for this article – it’s been used for decades. Possibly credit goes to Chris, the brilliant Clifford Chance tax partner who trained me. ↩︎

Assuming a 1/3 fall in the 750,000 incorporations we currently see each year. ↩︎