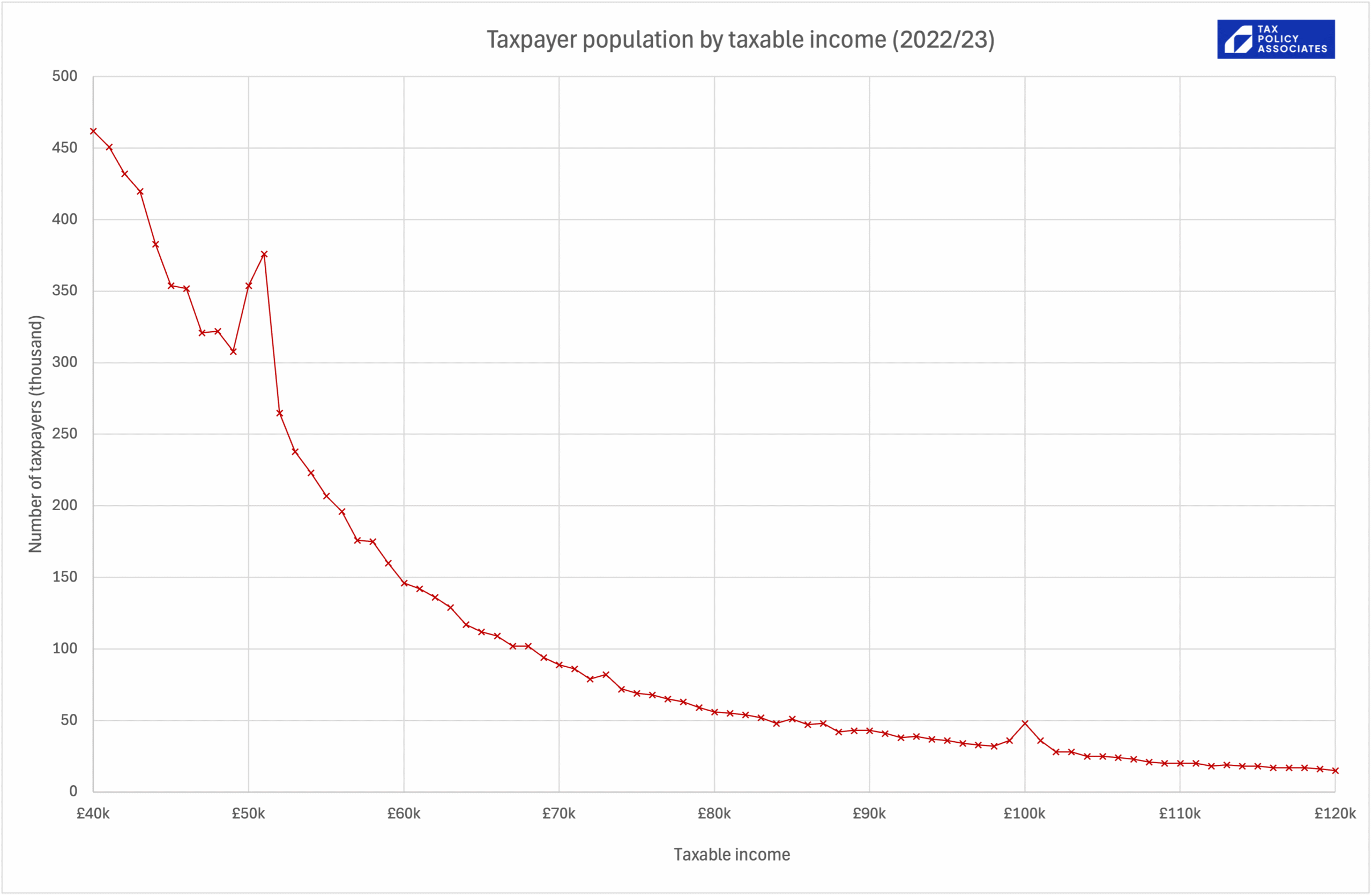

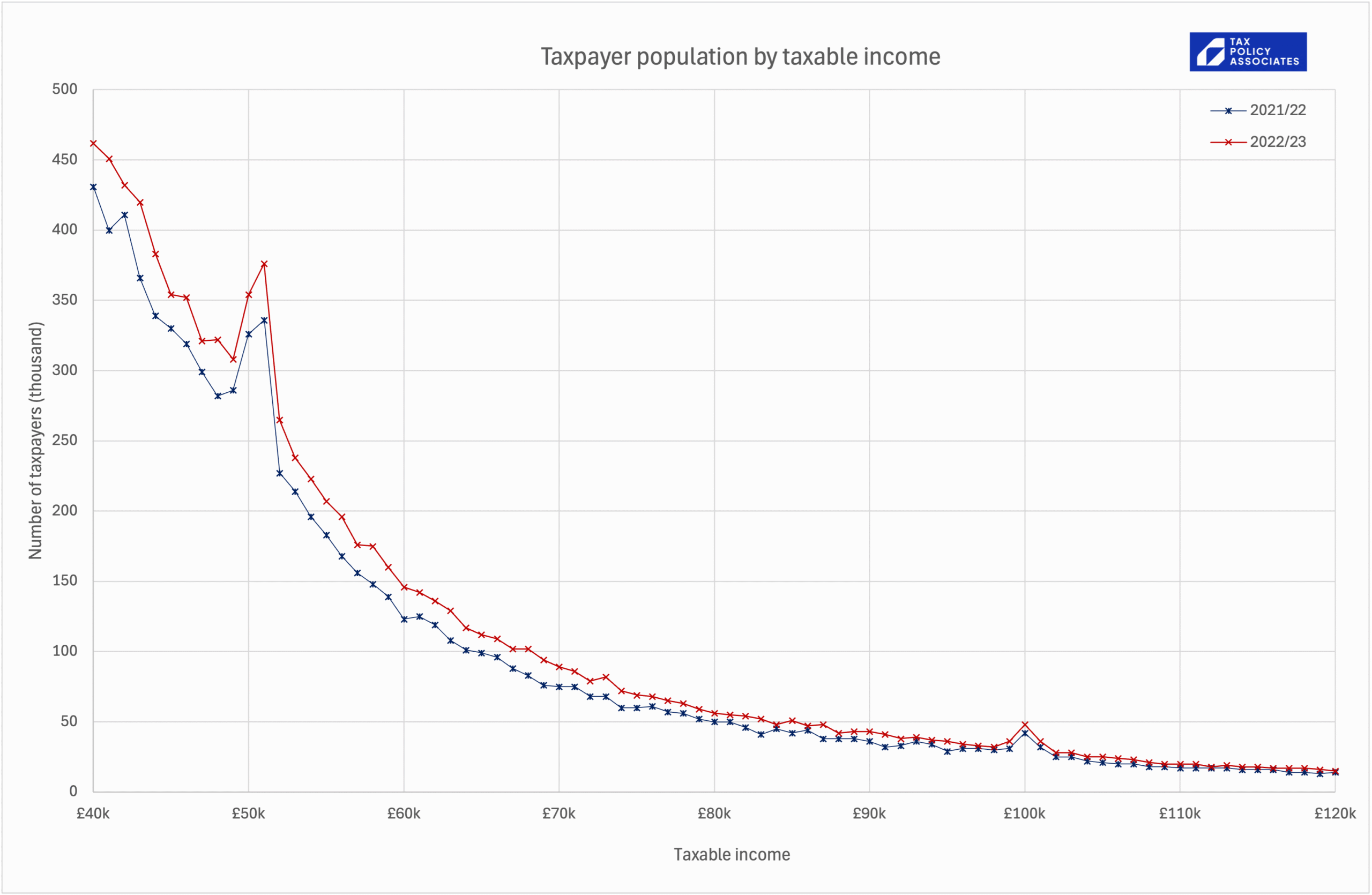

Samuel Leeds is a self-proclaimed “property guru”. He makes substantial sums by using hard-sell tactics and conspiracy theories to sell expensive courses on property investment to people who can’t afford it. Mr Leeds makes an array of claims on social media about how to “pay zero tax” and “learn the tax loopholes that the rich use“. We’ve reviewed these claims, and many are simply wrong. One is particularly egregious: the idea that you can repeatedly buy a dilapidated property, refurbish it and sell it, and claim main residence capital gains tax relief each time. Mr Leeds says he’s used this “strategy” himself multiple times. But the strategy doesn’t work – there are rules that specifically prevent it. If Mr Leeds really used the “strategy” then it wasn’t clever tax planning, but a failed attempt at tax avoidance – and he may owe significant tax to HMRC.

Mr Leeds claims tax expertise beyond most accountants. The reality is repeated, basic errors. That raises an obvious question about everything else he sells.

The Leeds “flipping” scheme

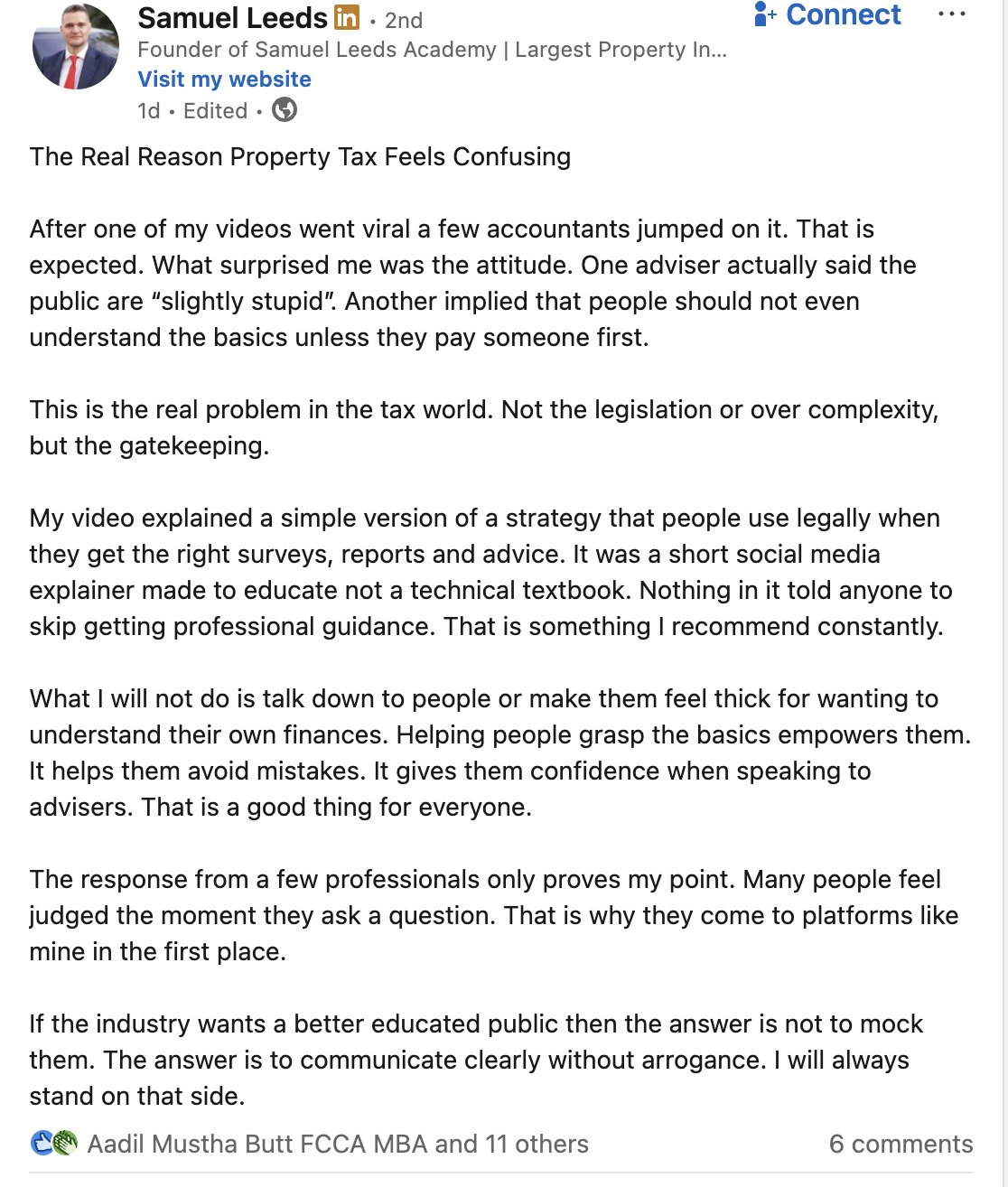

Samuel Leeds says he knows a lot about tax:

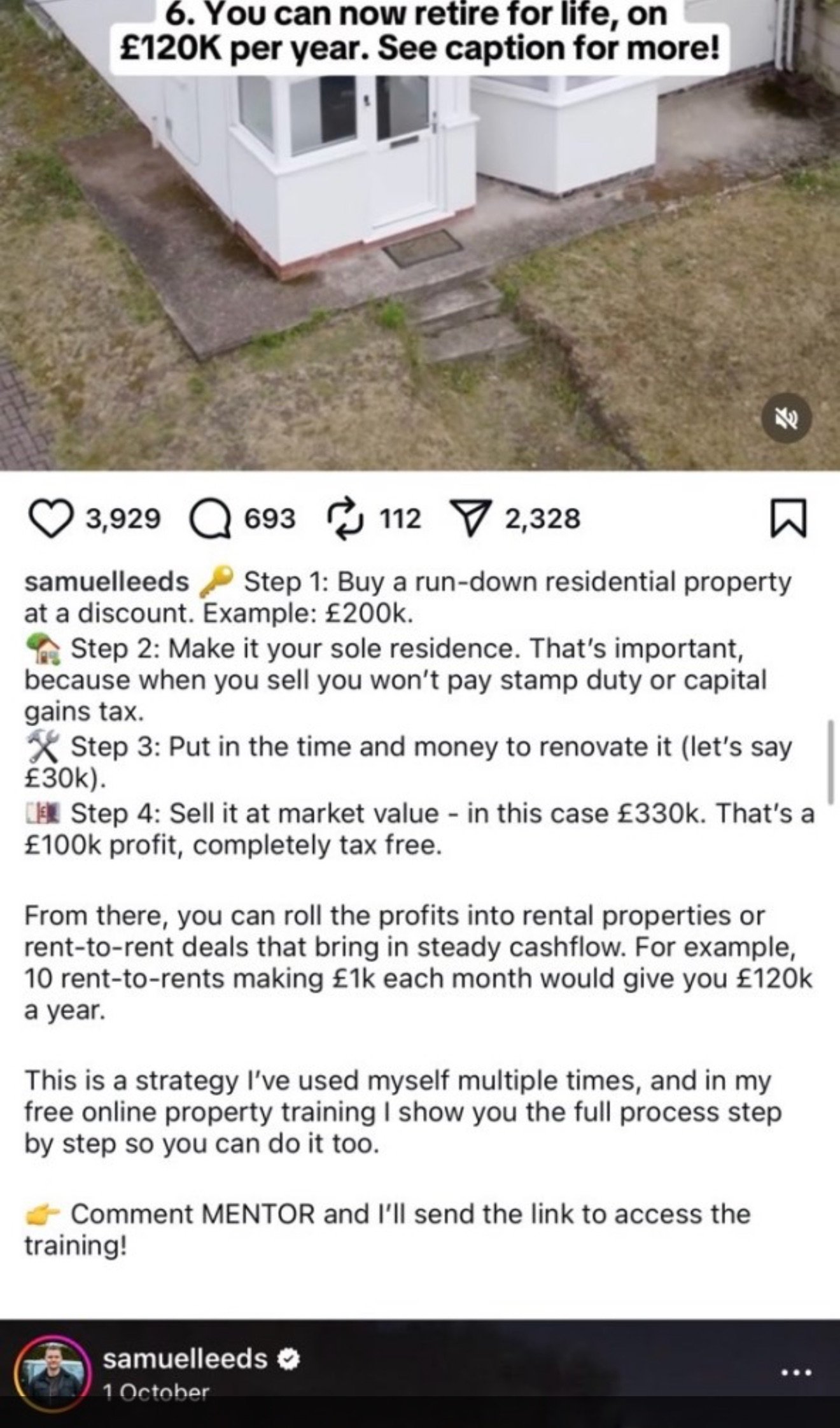

Here’s one of his claims:

It’s a simple claim: that you can buy a run-down property, renovate it, sell it – and the sale is exempt from capital gains tax. Mr Leeds says he’s done this “multiple times”.

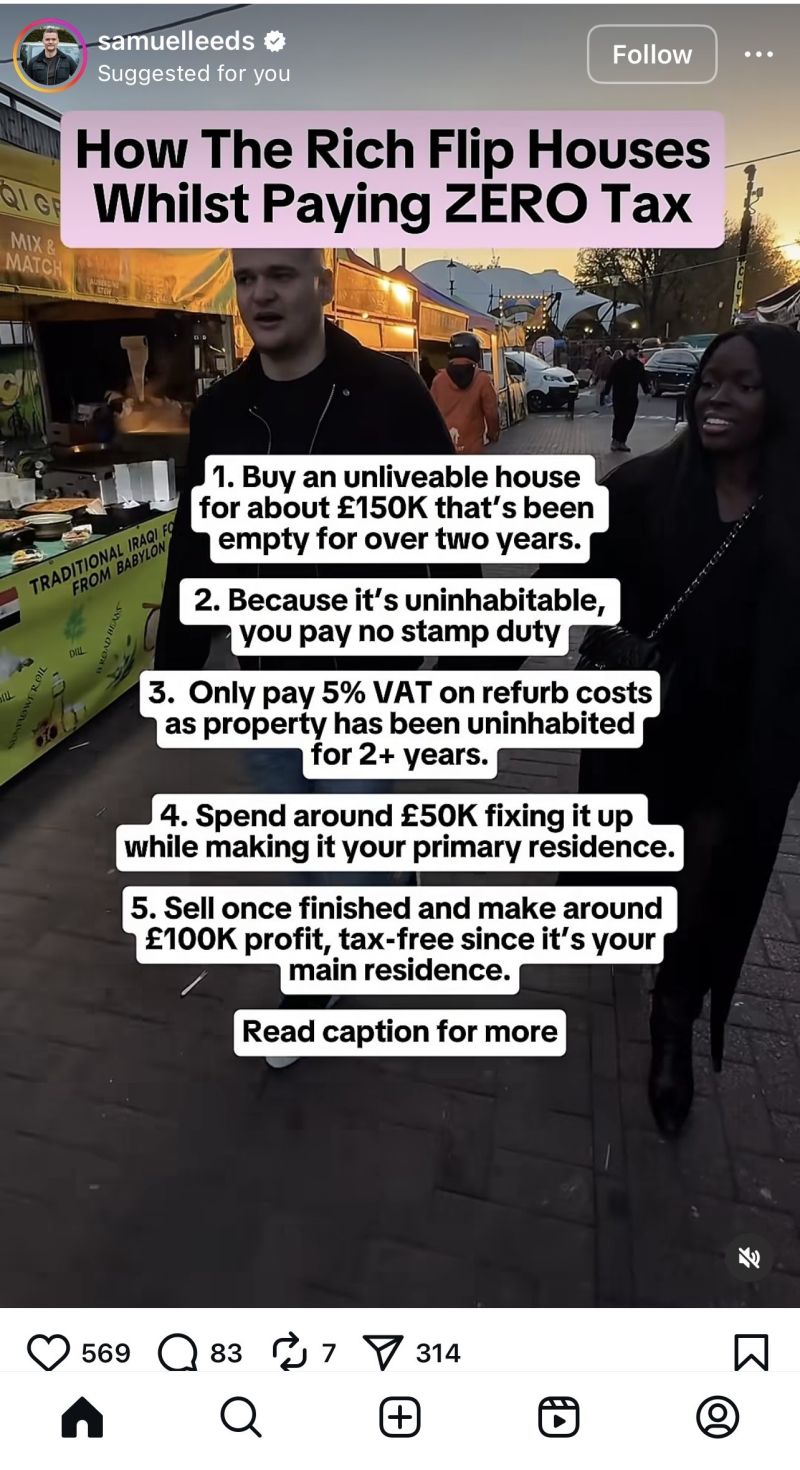

This is not a one-off. Mr Leeds makes the same claim in this video, saying you can “continue to do this again and again, completely tax free”:

And here:

And again here, here (in a video entitled “how to avoid capital gains tax”), here, here, here.

The idea that “the rich” move into uninhabitable houses to save tax is obviously daft. However there’s a bigger problem.

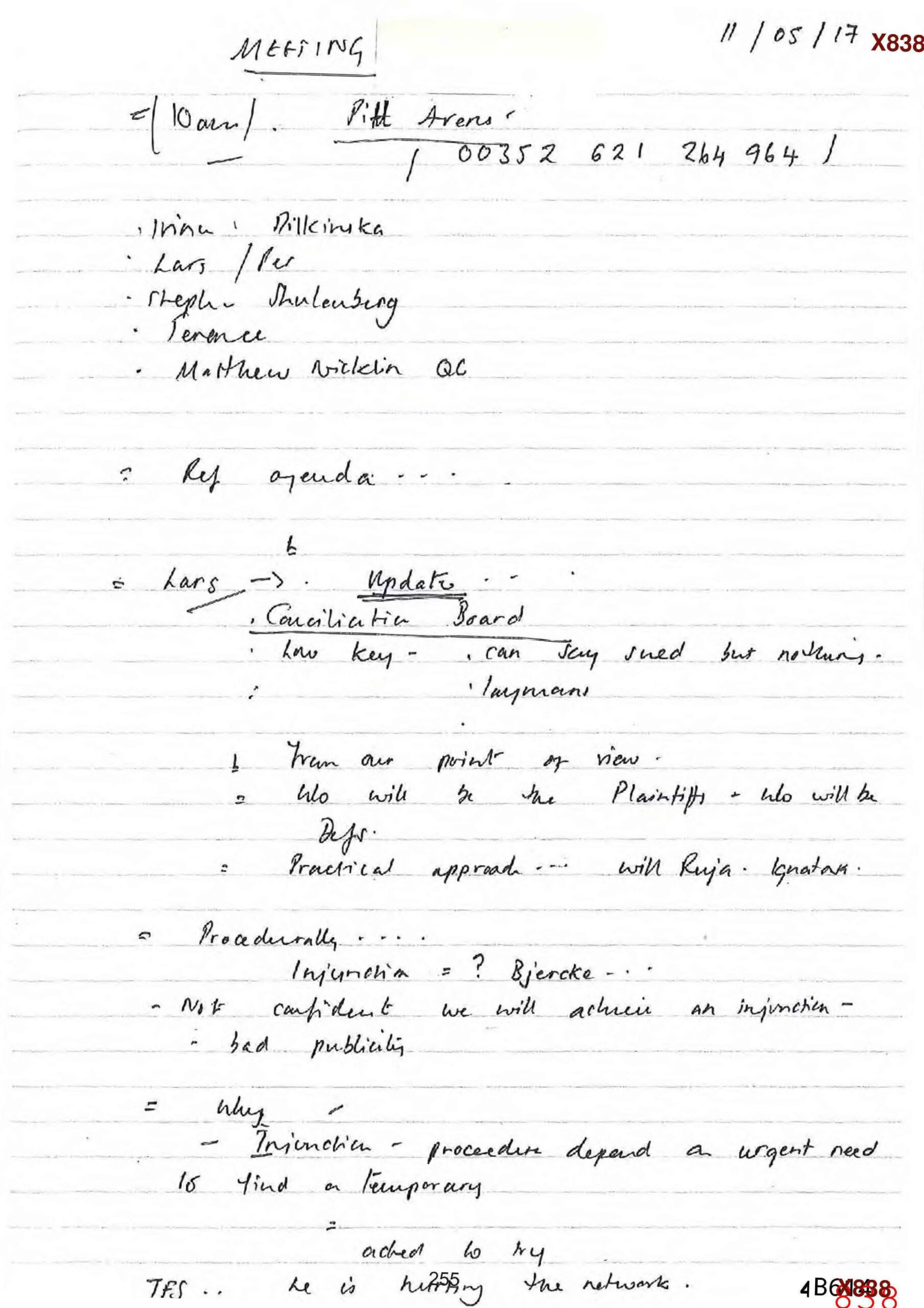

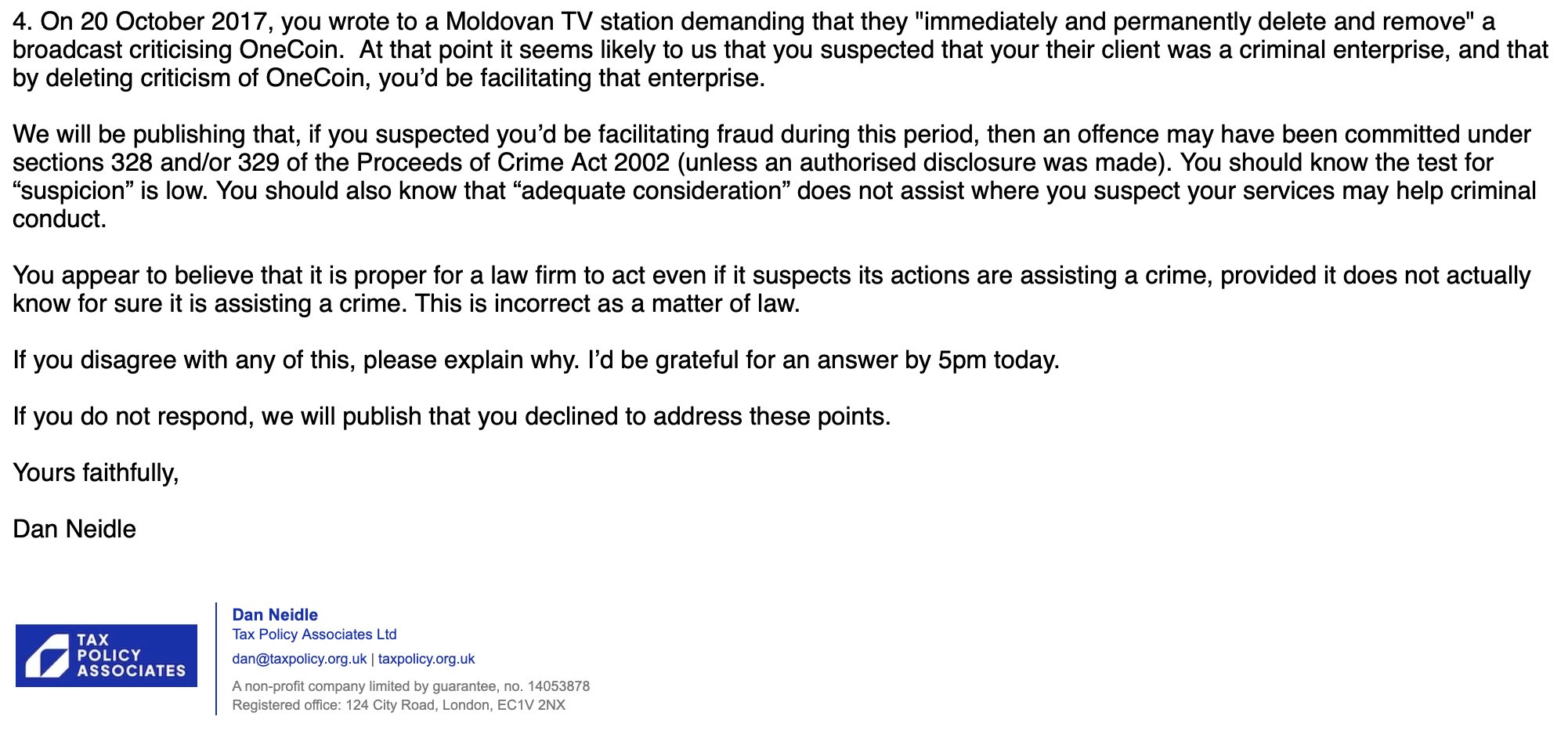

The legal reality

The main residence exemption is in sections 222 and 223 of the Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act 1992. This requires that a property is your “sole or main residence”. That’s an immediate problem for the Leeds scheme because, as the First Tier Tribunal said in the Ives case:

“The cases on the meaning of “residence” make it clear that there is a qualitative aspect to the question whether a person is occupying a property as a residence. This would lead us to conclude that a person who sets out to live in a property only whilst working on and subsequently selling it, and who has no real intention of making the property their settled home, is almost certainly not occupying the property as a residence.“

This is exactly what Mr Leeds is proposing.1

So the basic answer is that the Leeds scheme simply doesn’t work, because you may be living in the property, but it’s not your “main residence”.

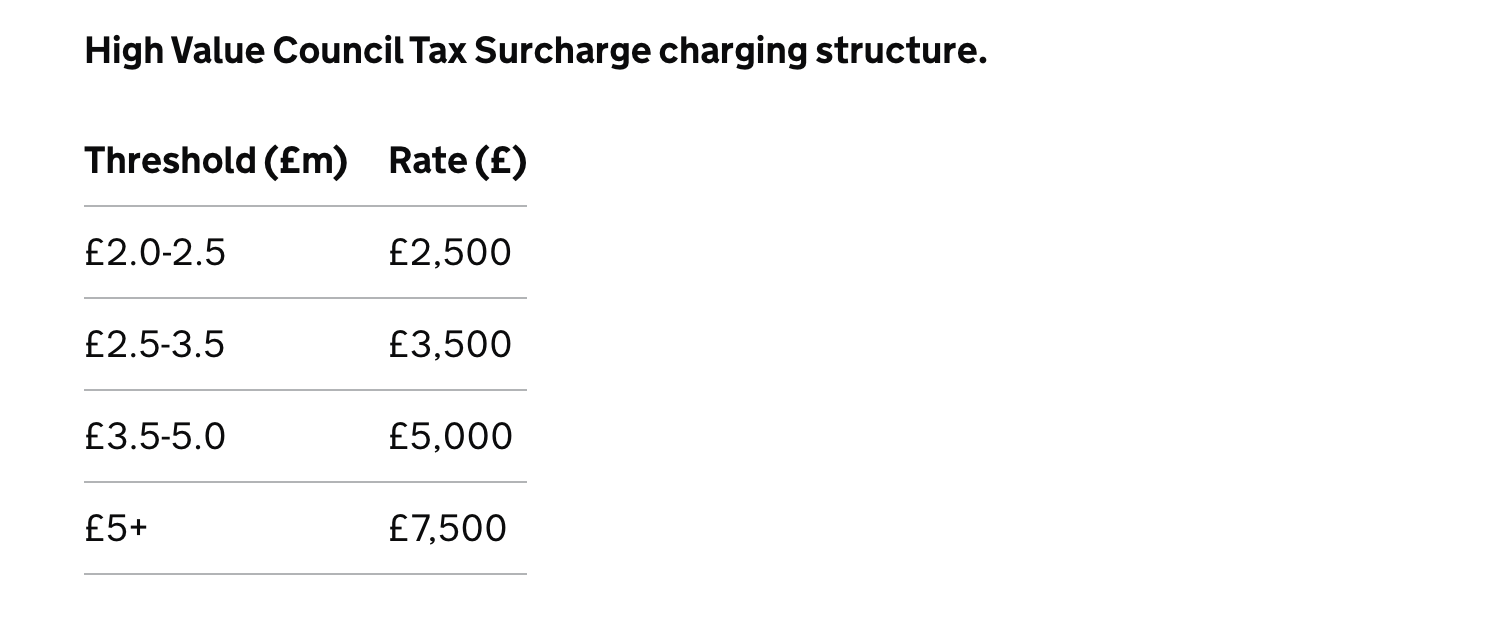

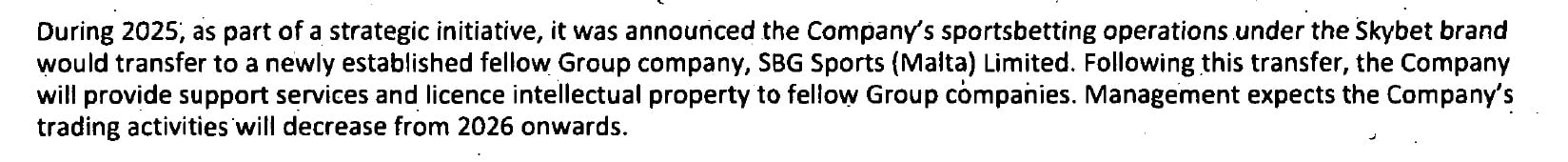

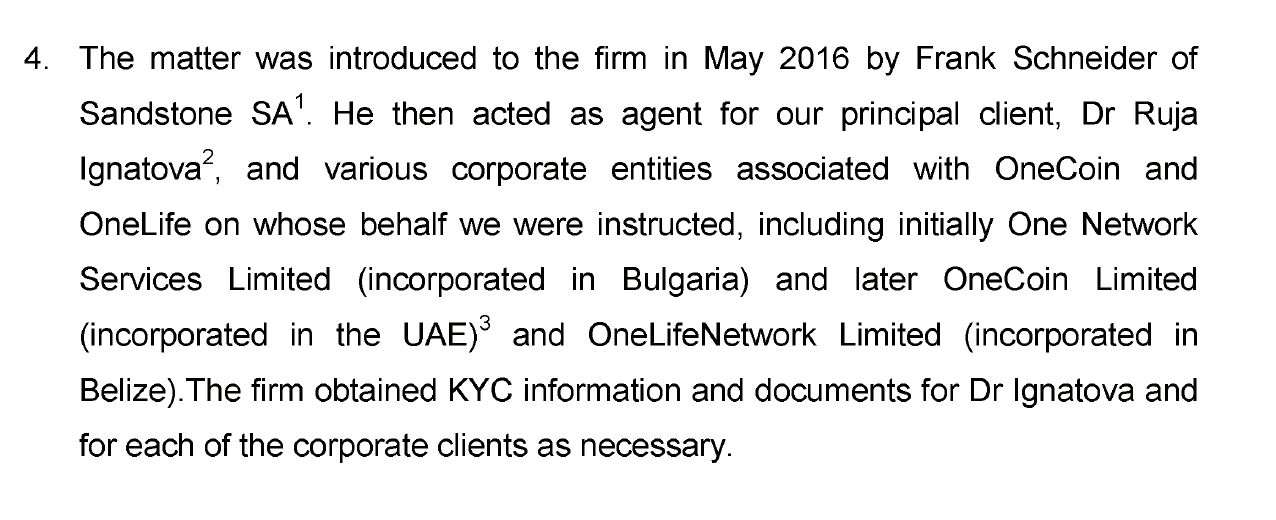

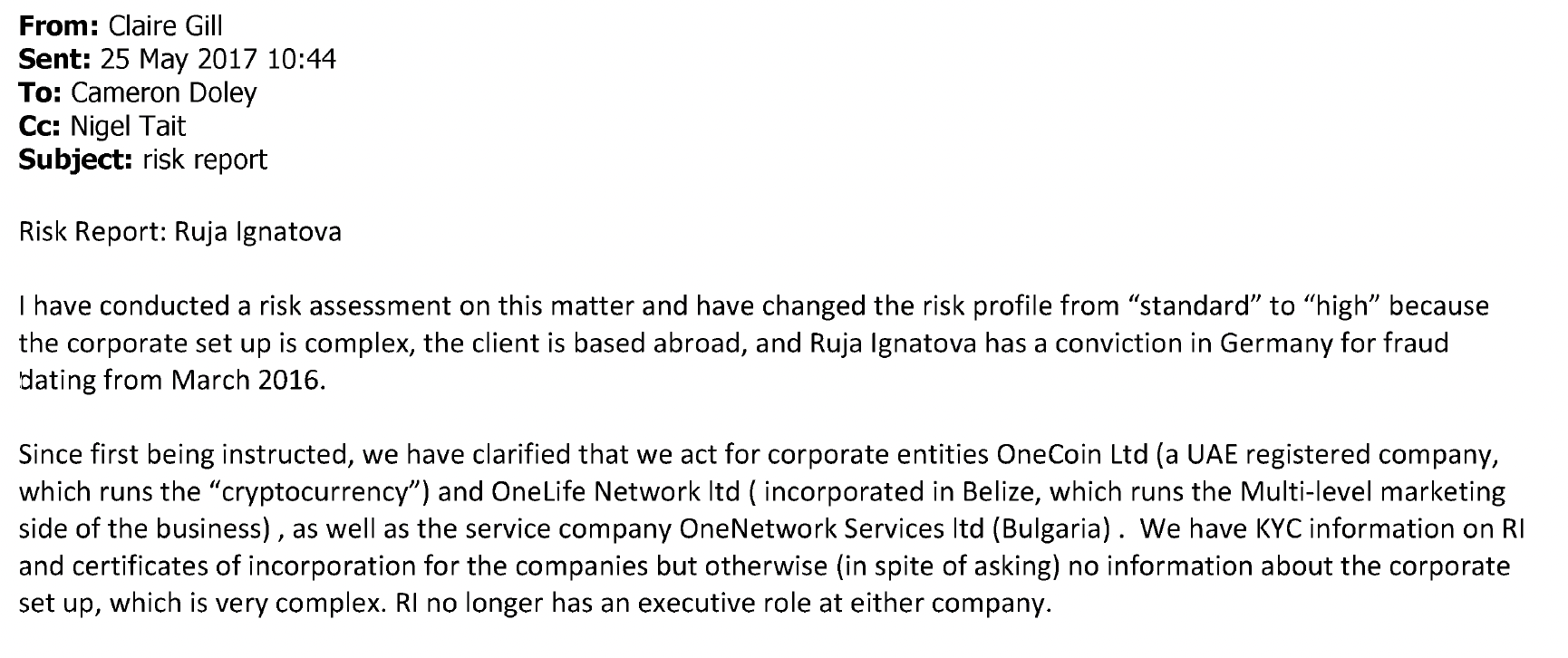

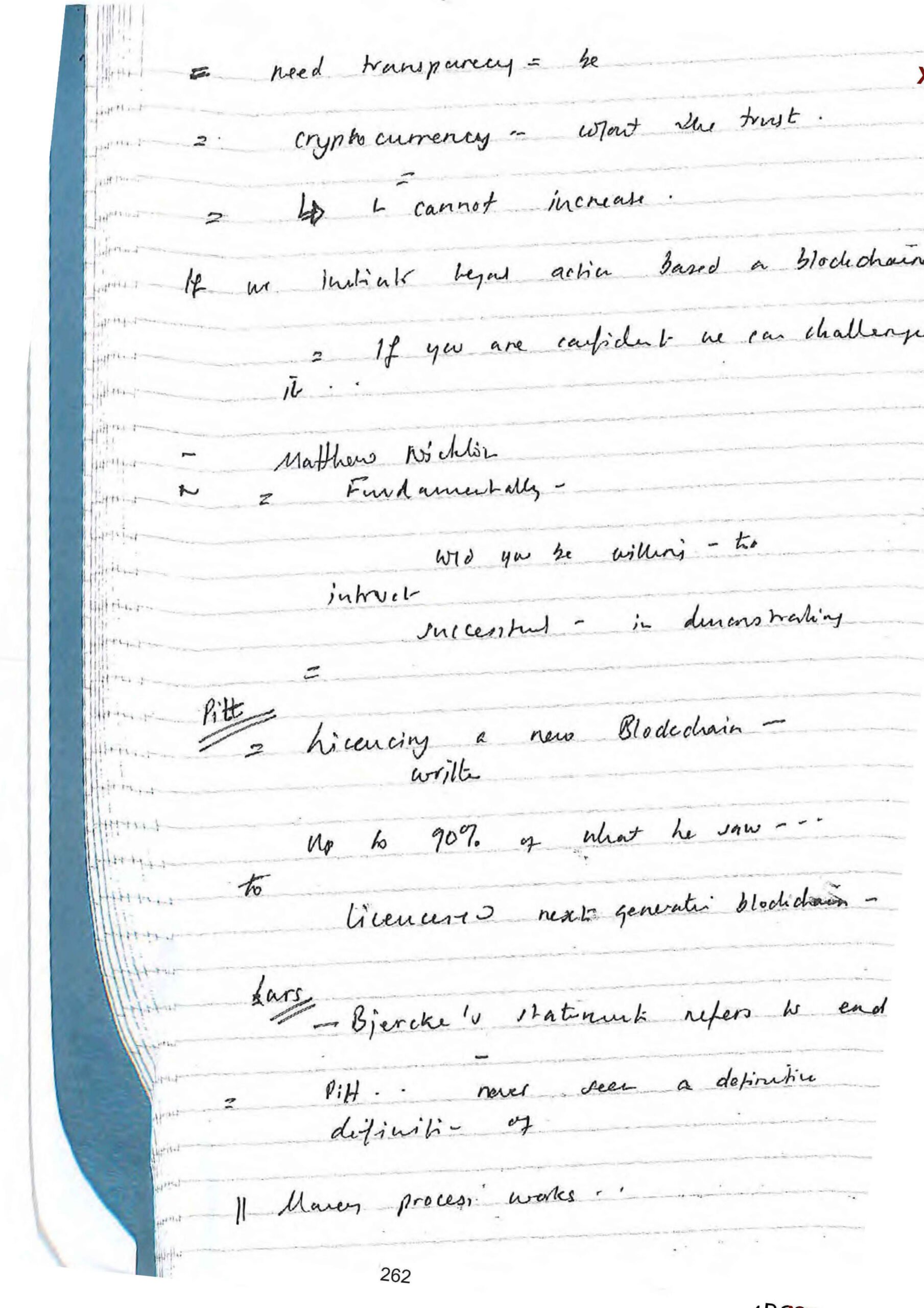

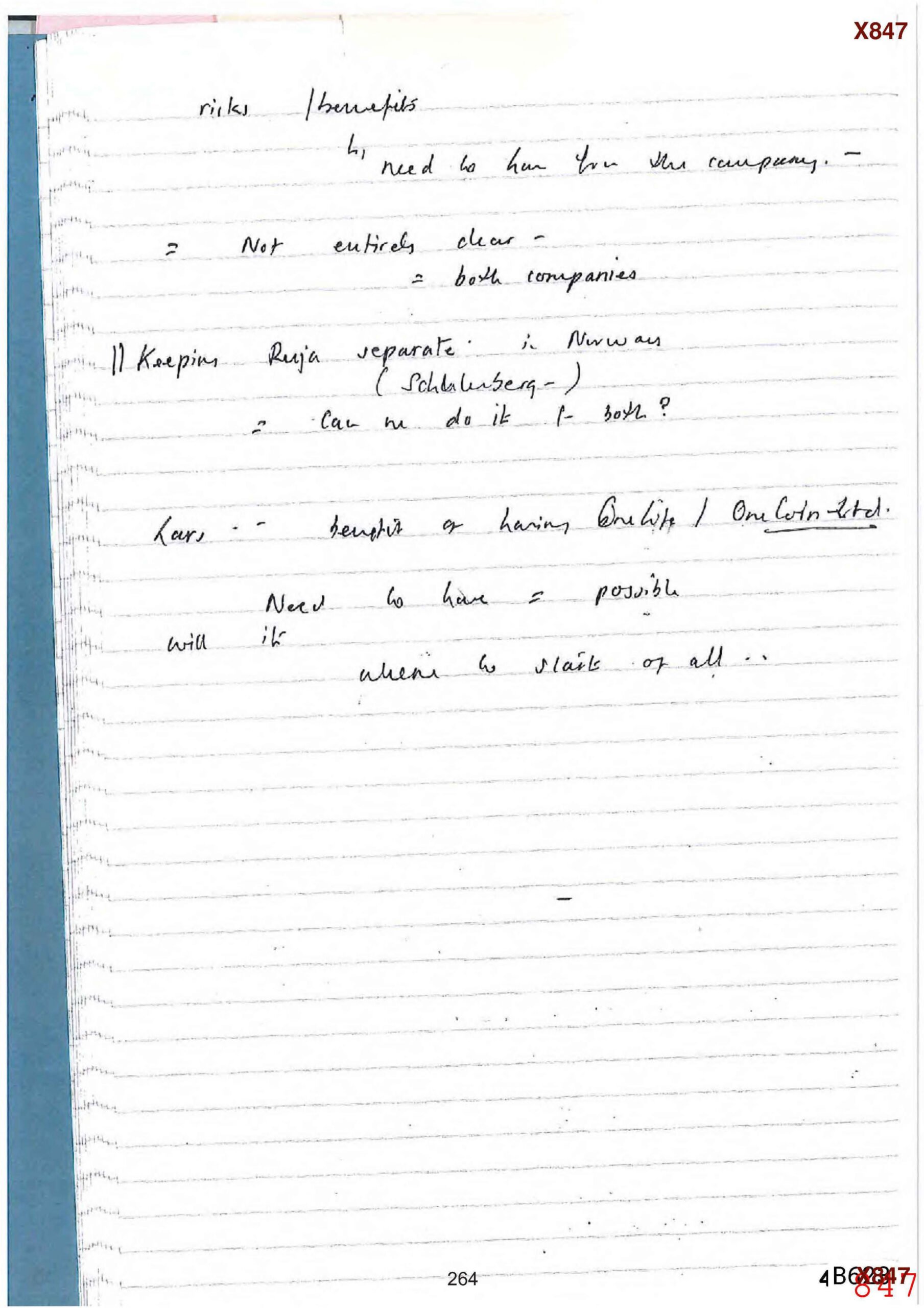

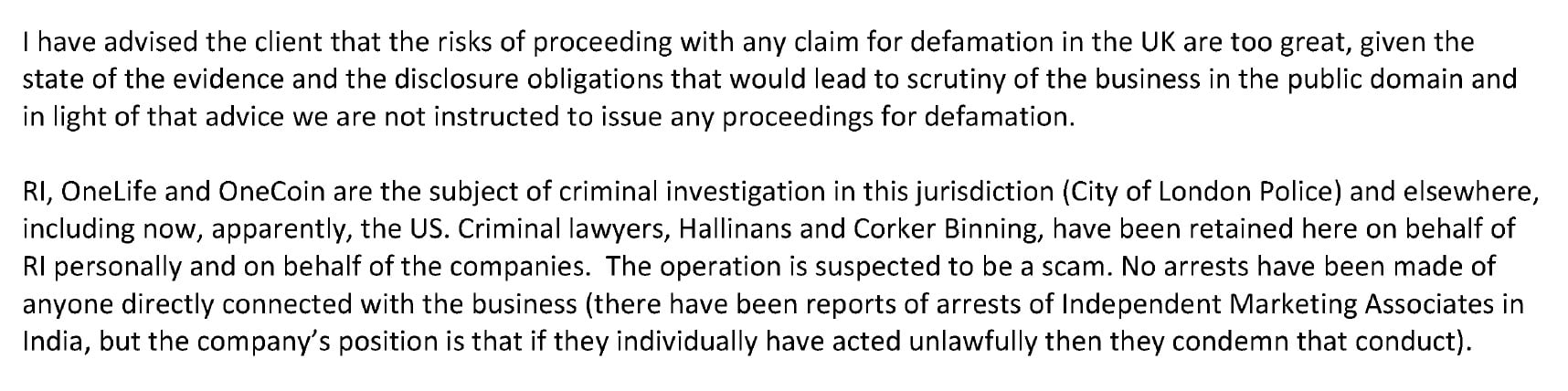

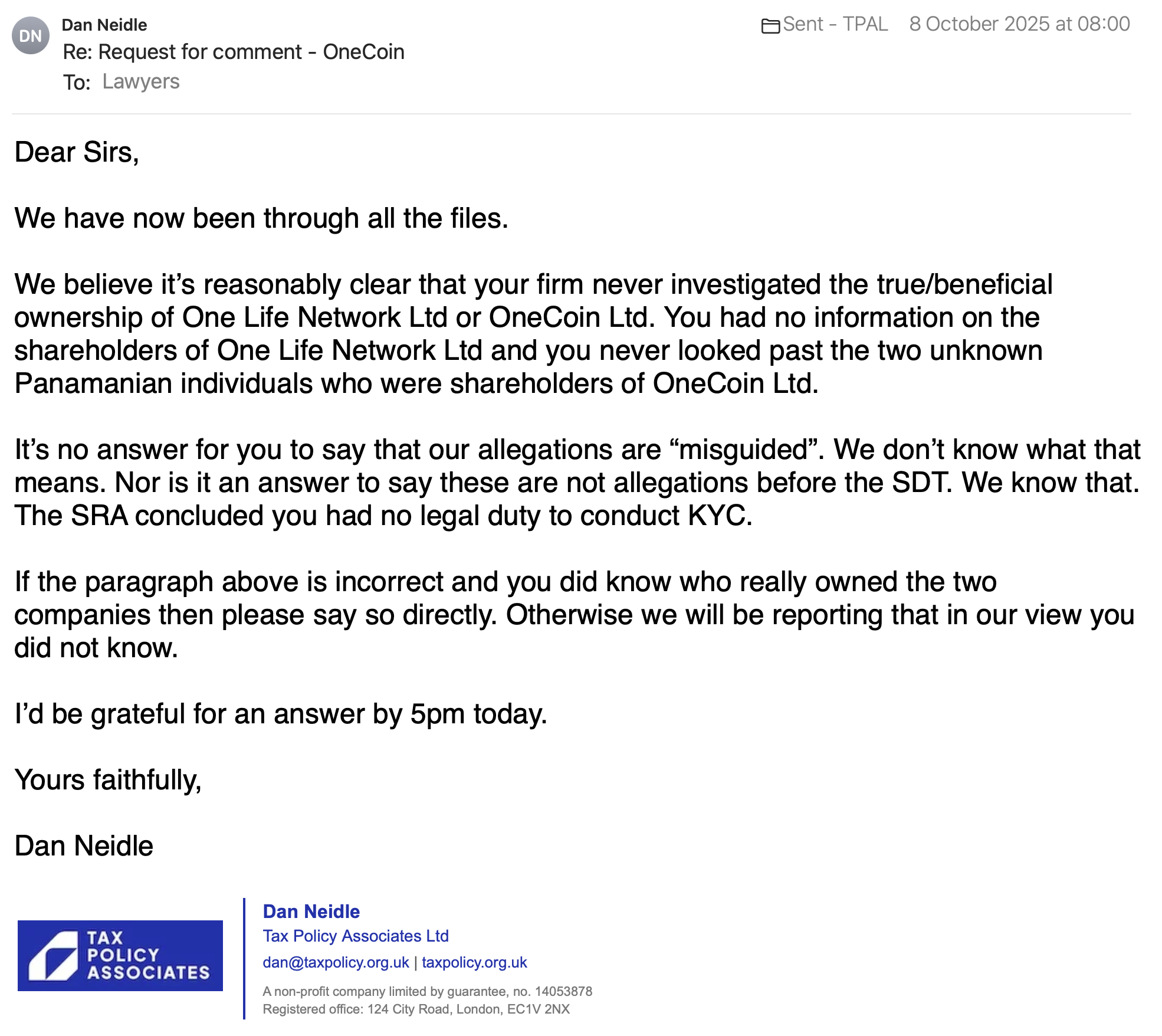

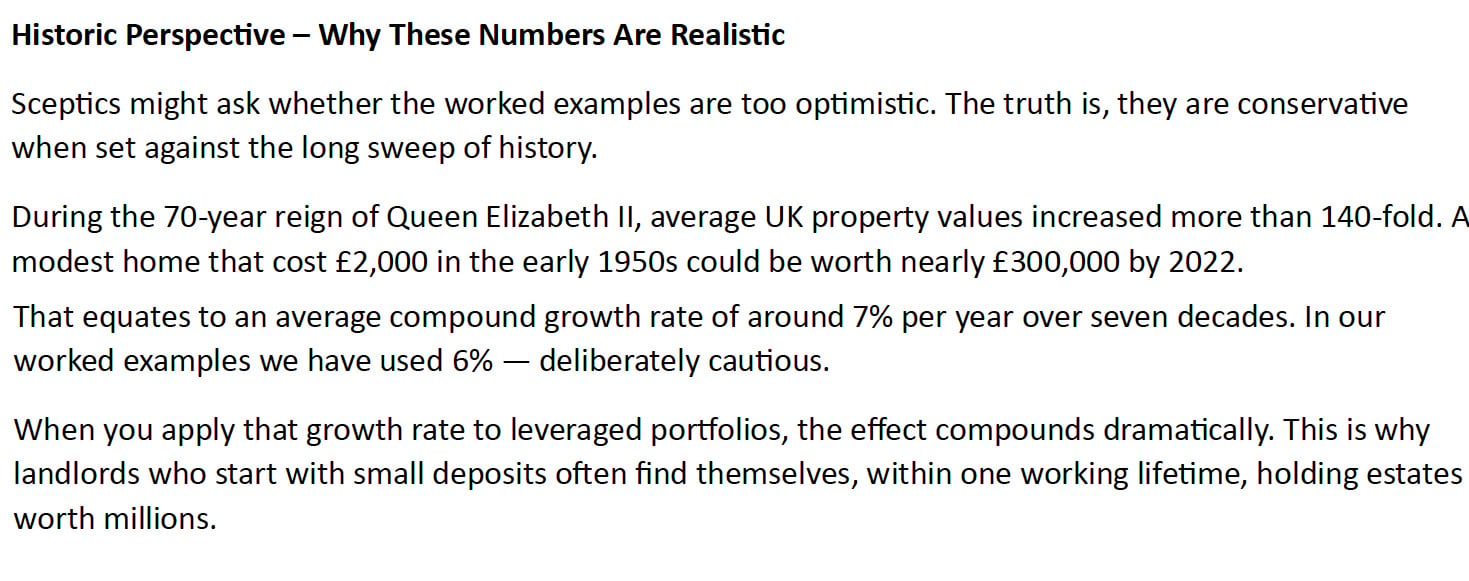

There’s a further problem – a specific exclusion from the exemption in section 224(3) of the Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act 1992:

By his own admission, Mr Leeds’ purpose for acquiring the properties was to realise a gain. So, even if each of the properties was his “main residence” (doubtful), section 224(3) applied and he should have paid capital gains tax.

That’s not the only way this goes wrong – repeated acquiring, renovating and “flipping” of properties may constitute a property development trade2, if the acquisition was for the purpose of renovating and “flipping”.3 If it does, then the profits are taxable to income tax rather than capital gains tax – a higher rate, and no main residence exemption.4

None of this is very obscure or difficult, and in our experience the law is widely understood by property investors.

We can see only one case where Mr Leeds warns people that in fact the main residence exemption is not available if you buy with the intention to sell.5 So, given he knows this, why does he say everywhere else – very clearly – that you can use the exemption in such a case?

Other claims

Mr Leeds makes a variety of other tax claims:

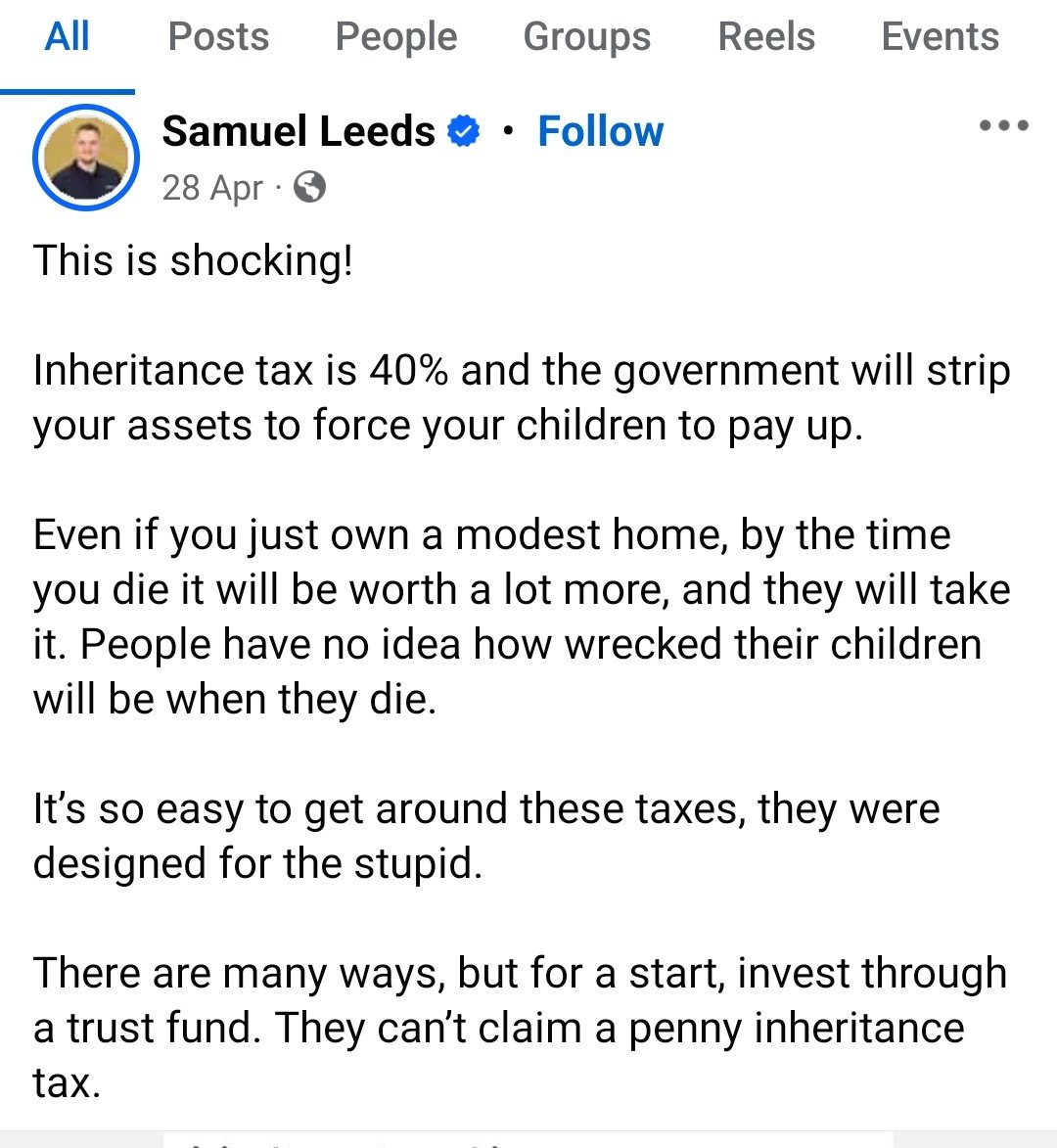

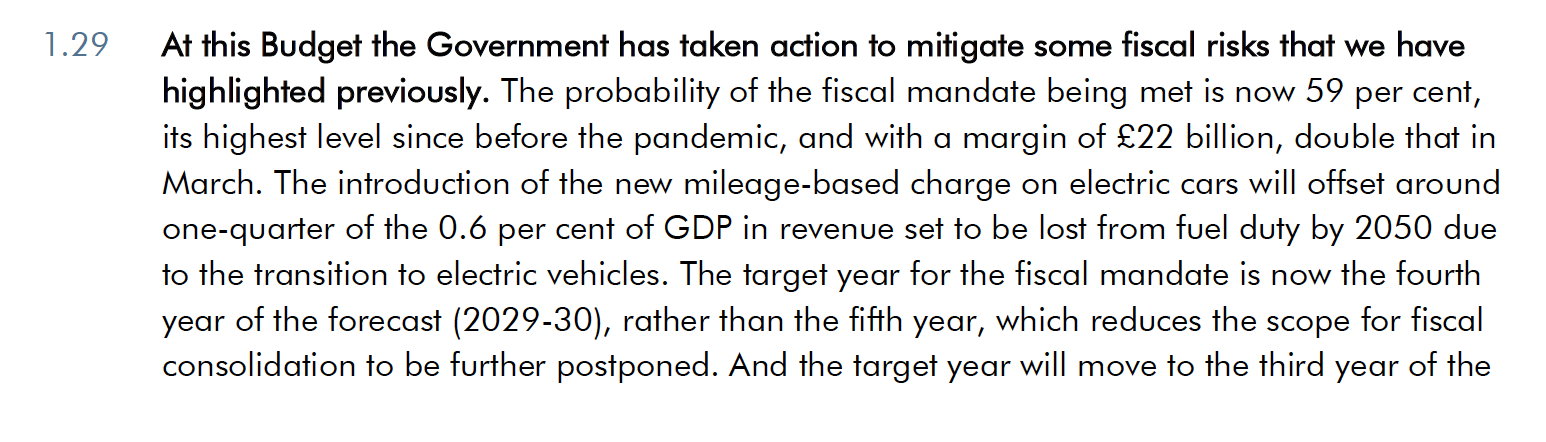

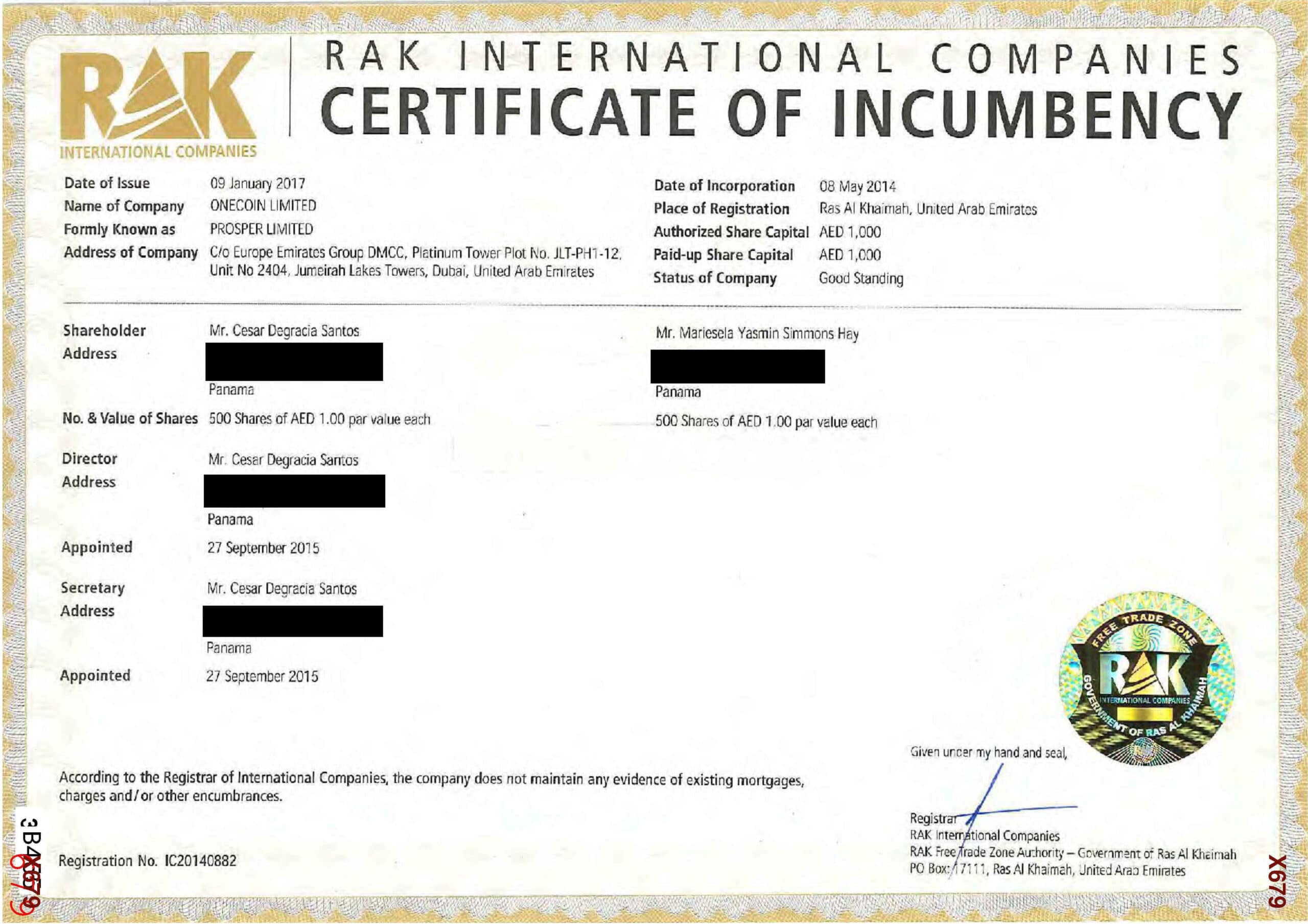

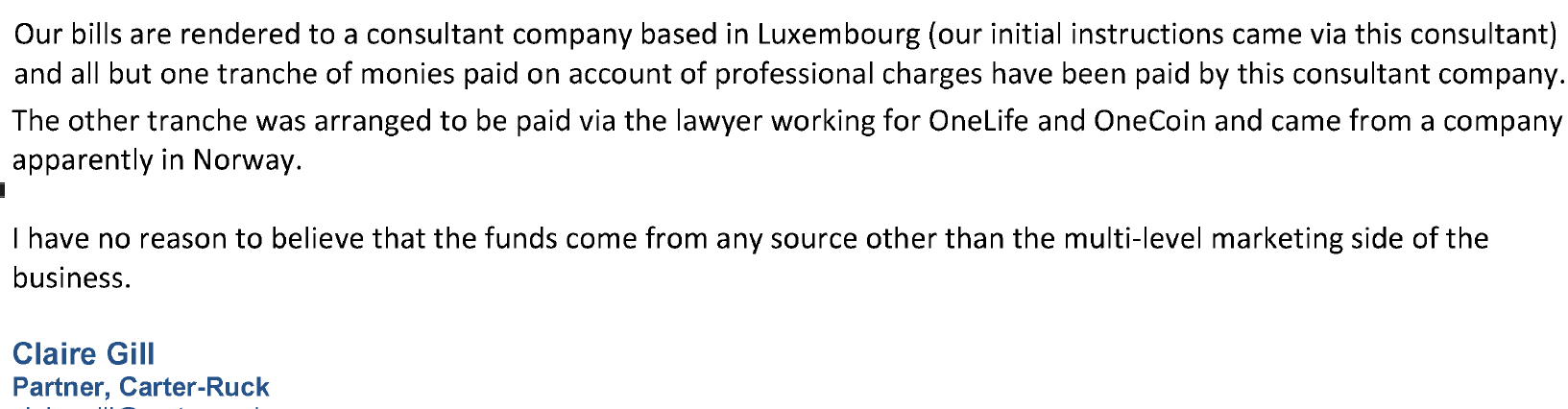

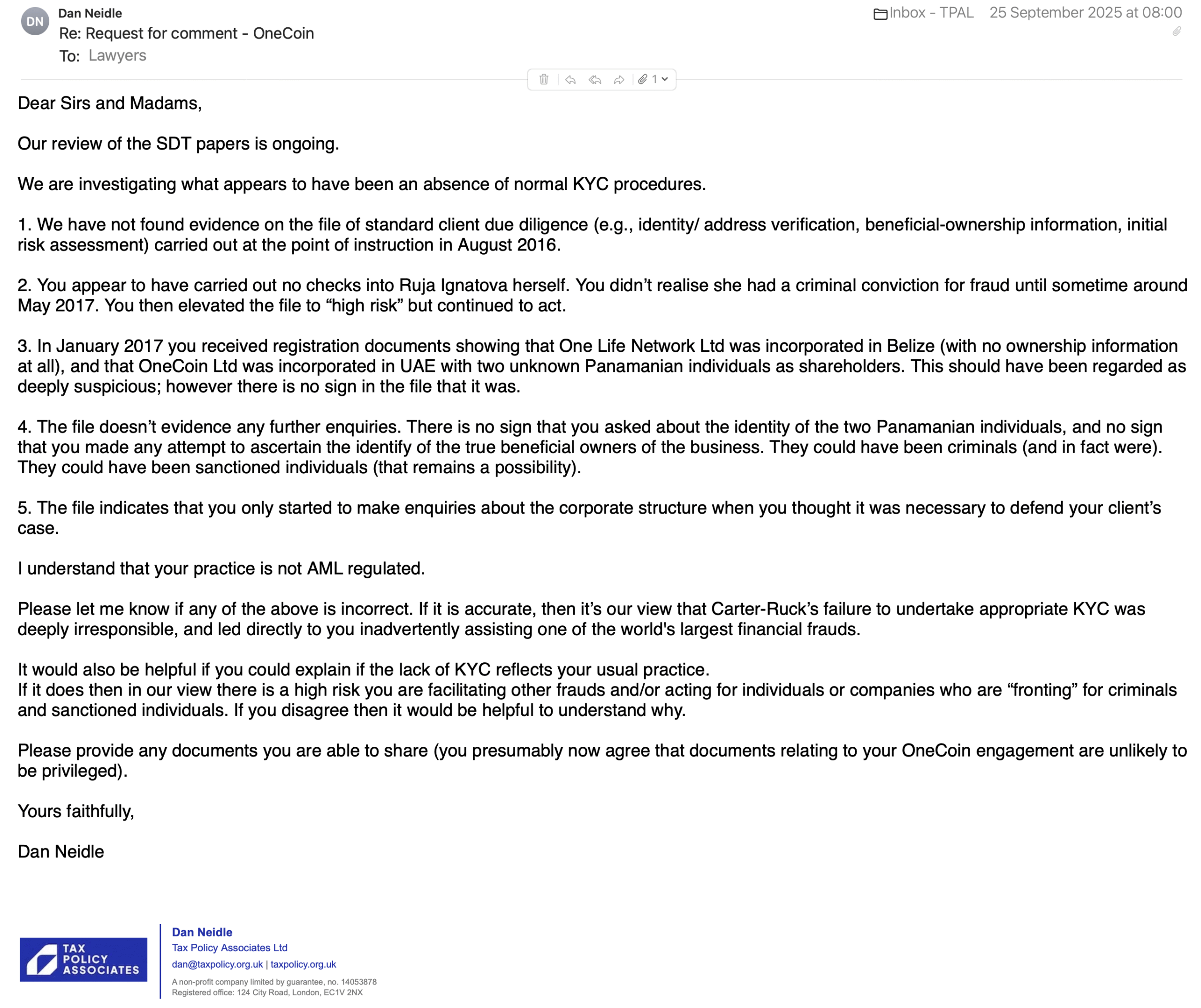

Trusts

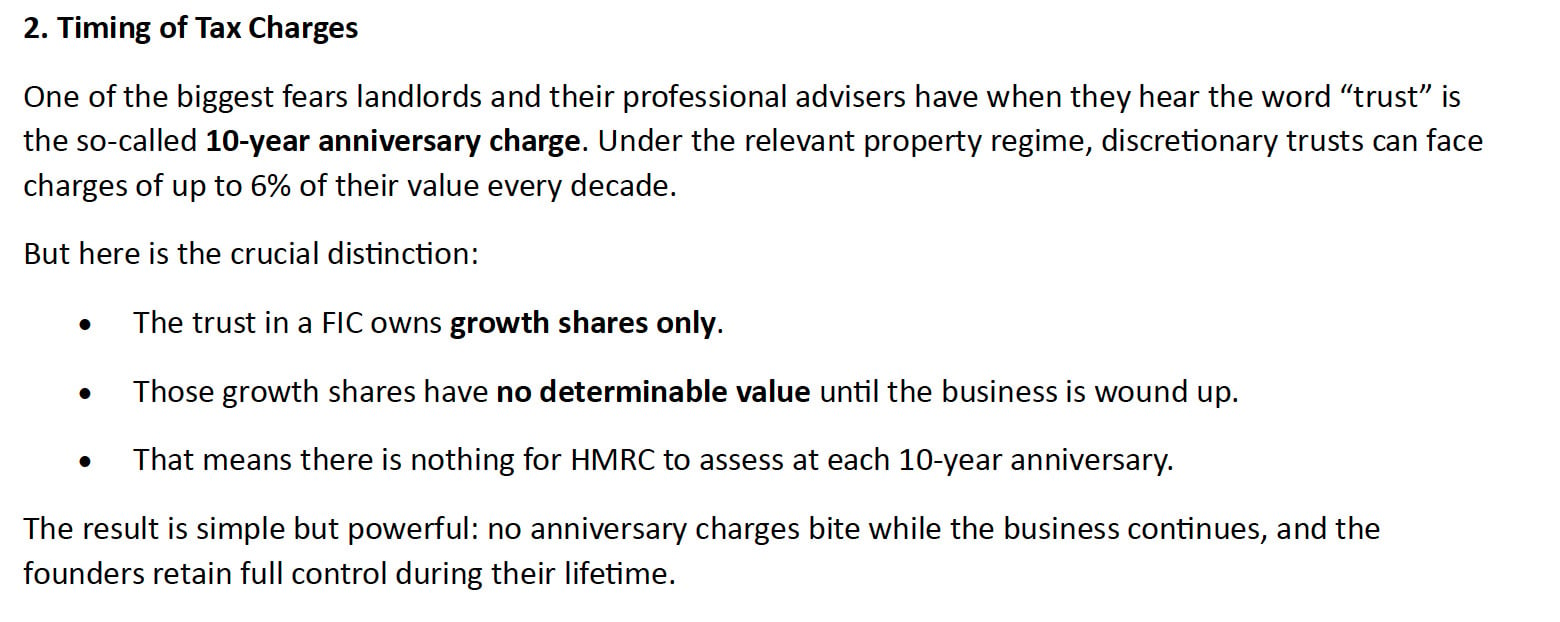

For most people, trusts are not good tax planning. Putting property in trust (above the £325k zero rate band) is a lifetime chargeable transfer giving rise to an immediate 20% inheritance tax charge. The trust is then subject to an inheritance tax “anniversary charge” of up to 6% of the trust’s asset value every ten years (again above the £325k zero rate band).6 There are lots of people selling trust schemes which supposedly avoid these taxes – the schemes we’ve reviewed do not work.7

IHT planning

Here’s another claim from Mr Leeds:

This is another strategy that doesn’t work. If you continue to live in your house after gifting it to your kids, then the “reservation of benefit” rules apply, and inheritance tax applies as if you hadn’t given the house away.89

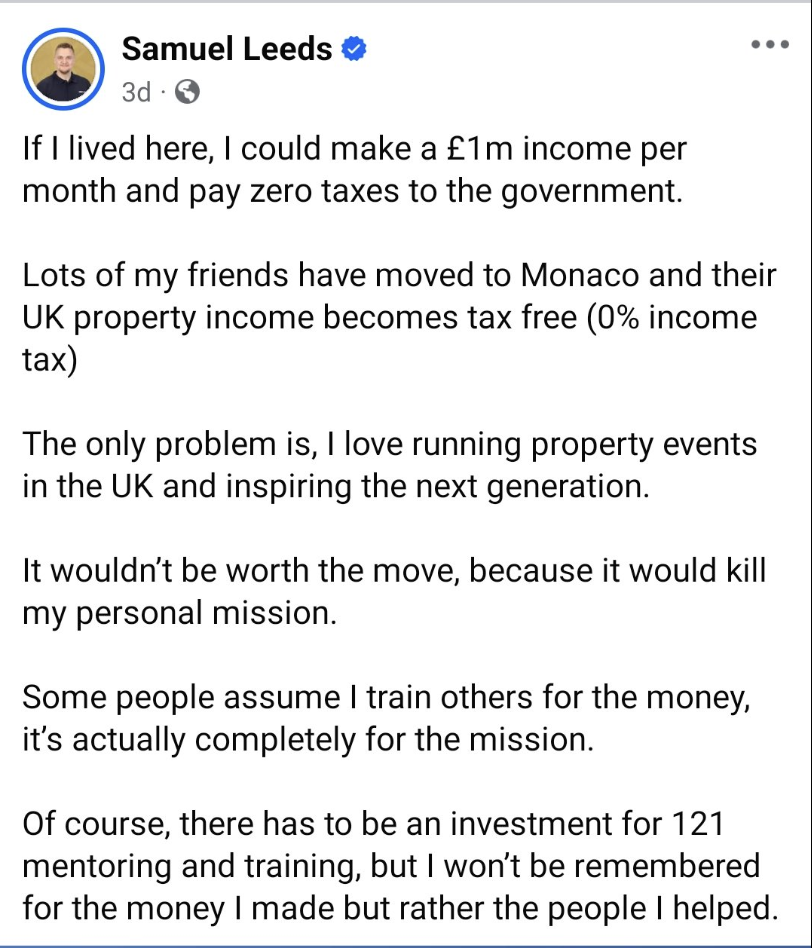

Holding UK property offshore

And here’s Mr Leeds claiming last year that someone living in Monaco pays no UK tax on UK property income:

This is a basic misunderstanding of the fundamental principle of UK property taxation: UK property income is taxable no matter where in the world you live.10 Our founder, Dan Neidle, challenged Mr Leeds on this in 2024 – Mr Leeds conceded he had “misunderstood”.

Employing your kids

In this video, Mr Leeds suggests that your company can employ your spouse or your kids (from as young as 13 years old), pay them £12,500 each, and so extract cash from the company tax-free.11

If (as seems likely) the spouse and children aren’t doing anything for their money, or just doing trivial tasks, then it’s non-deductible for the company. If the children are under 14 then their employment may be illegal, with no tax deduction available even if they are doing genuine work.

HMRC may also challenge this as a diversion of the owner’s income. The usual approach is to deny a corporation tax deduction where the payments are not wholly and exclusively for the trade, and/or to treat the payments as the owner’s remuneration in substance. In some cases HMRC may also invoke specific anti-avoidance rules, including the settlements rules.

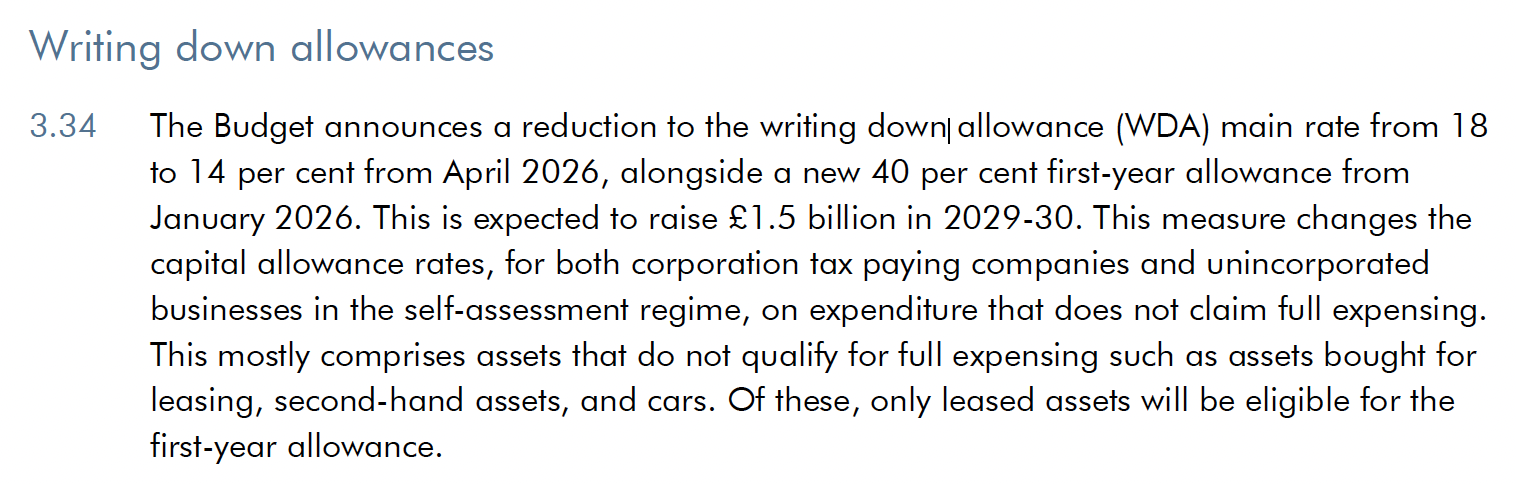

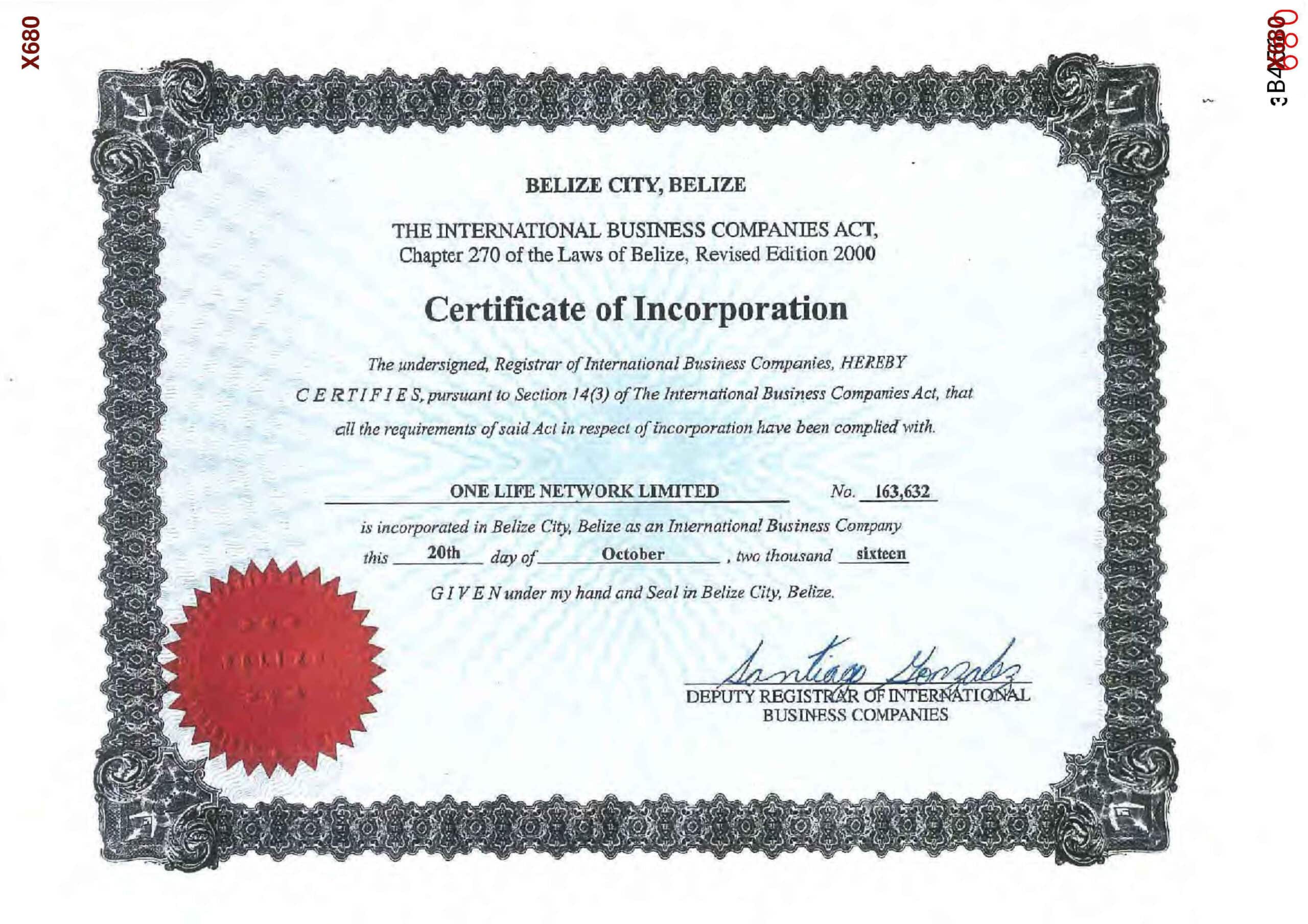

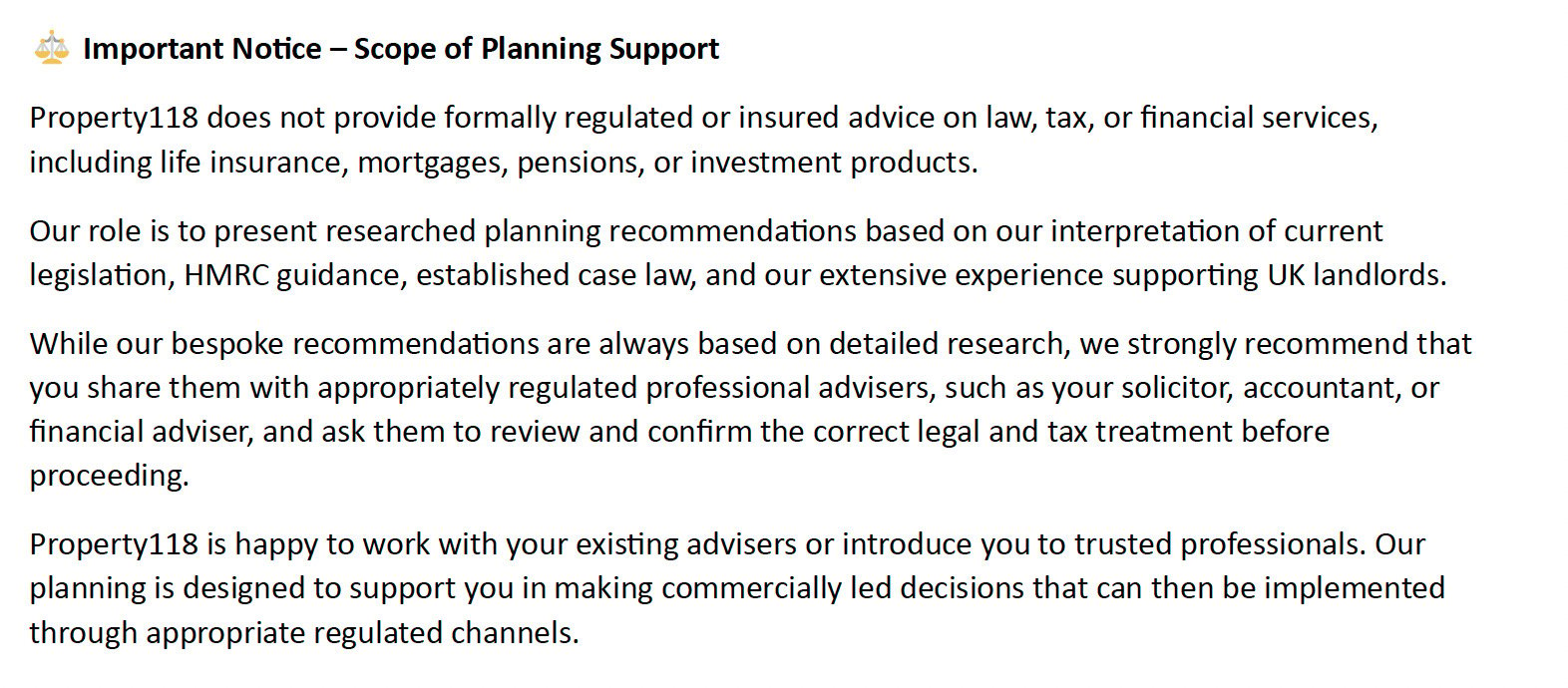

Stamp duty and VAT on “uninhabitable” properties

This video makes two misleading claims about saving tax when buying uninhabitable properties:

First, an incorrect explanation of the stamp duty12 rule for uninhabitable properties:

For example, let’s say you buy a rundown house for £150,000 as a buy/refurbish/refinance or a flip investment property. Normally, as a second property, an investment property, you’d pay 5% [stamp duty] on the first £250,000. That’s £7,500 cash up front in stamp duty tax. But because the property lacks a kitchen, bathroom, or heating, it qualifies as uninhabitable. So you pay zero stamp duty up to the first £150,000 and then just 5% on any excess amount, saving you £7,500. The key is getting a RICS surveyor to confirm that the property is uninhabitable.

This is not correct. The “uninhabitable property exemption” (strictly the question of whether a property is “suitable for use as a dwelling“) will only apply in unusual cases. HMRC guidance at the time was clear:13

A very high proportion of the SDLT repayment claims that HMRC receives in relation to this area are wrong. Customers should be cautious about being misled by repayment agents into making incorrect claims.

Whether a property has deteriorated or been damaged to the extent that it no longer comprises a dwelling is a question of fact and will only apply to a small minority of buildings.

If the building was used as a dwelling at some point previously, it is fundamentally capable of being so used again (assuming there is no lack of structural or other physical integrity preventing such use). Such a building is likely to be considered “suitable for use as a dwelling”, even if not ready for immediate occupation at the time of the land transaction.14

It follows that a surveyor’s opinion on the current condition does not mean that the exemption applies.15 The fact that (for example) a property temporarily lacks a kitchen or bathroom, or doesn’t have heating, doesn’t mean it’s not a dwelling.

Second, a misleading explanation of VAT:

Let me explain how VAT reclaim on renovations works. If you’re about to renovate a property, this next law could save you thousands in VAT value added tax savings.

If a property has been empty, like many have for two years or more, you qualify for a reduced 5% VAT on renovation costs instead of 20%. For example, say you buy a rundown house that’s been vacant for a few years, you budget £100,000 for the refurb, normal VAT will be 20%, which is a £20,000 tax bill. But the reduced VAT at 5% is just £5,000 meaning you’re saving £15,000. And to qualify for this relief, all you have to do is prove the property was empty with council tax records or utility bills, and then work with a VAT registered contractor to apply the discount.

The 5% rate for renovation of empty properties applies to building materials and works to the fabric of the building. HMRC treat several common refurbishment items as standard‑rated, including the erection/dismantling of scaffolding, professional fees (architects/surveyors/consultants), landscaping, hire of goods, and the installation of goods that are not ‘building materials’ (for example carpets or fitted bedroom furniture). In practice someone undertaking a £100k refurbishment will almost never qualify for the 5% rate on all of it.

Wear your brand

Here’s Mr Leeds saying that you can buy clothing with your branding and claim a tax deduction:

This is poor tax planning. You’re unlikely to get a tax deduction because the clothing isn’t “wholly and exclusively” for the purposes of the business. Worse, clothing is usually a “benefit in kind” and so taxable for employees – i.e. potentially a worse result for an owner-managed business than if you paid yourself a salary and used that to buy the clothes.

The strange thing is that the video above is from Autumn last year. But five years earlier, Samuel Leeds said that he’d tried claiming a deduction for branded clothing and it didn’t work:

“My clothes. I tried it. I tried getting my clothes tax deductible, and putting my name on it and stuff. Didn’t get it past HMRC. So I was, like, forget it.”

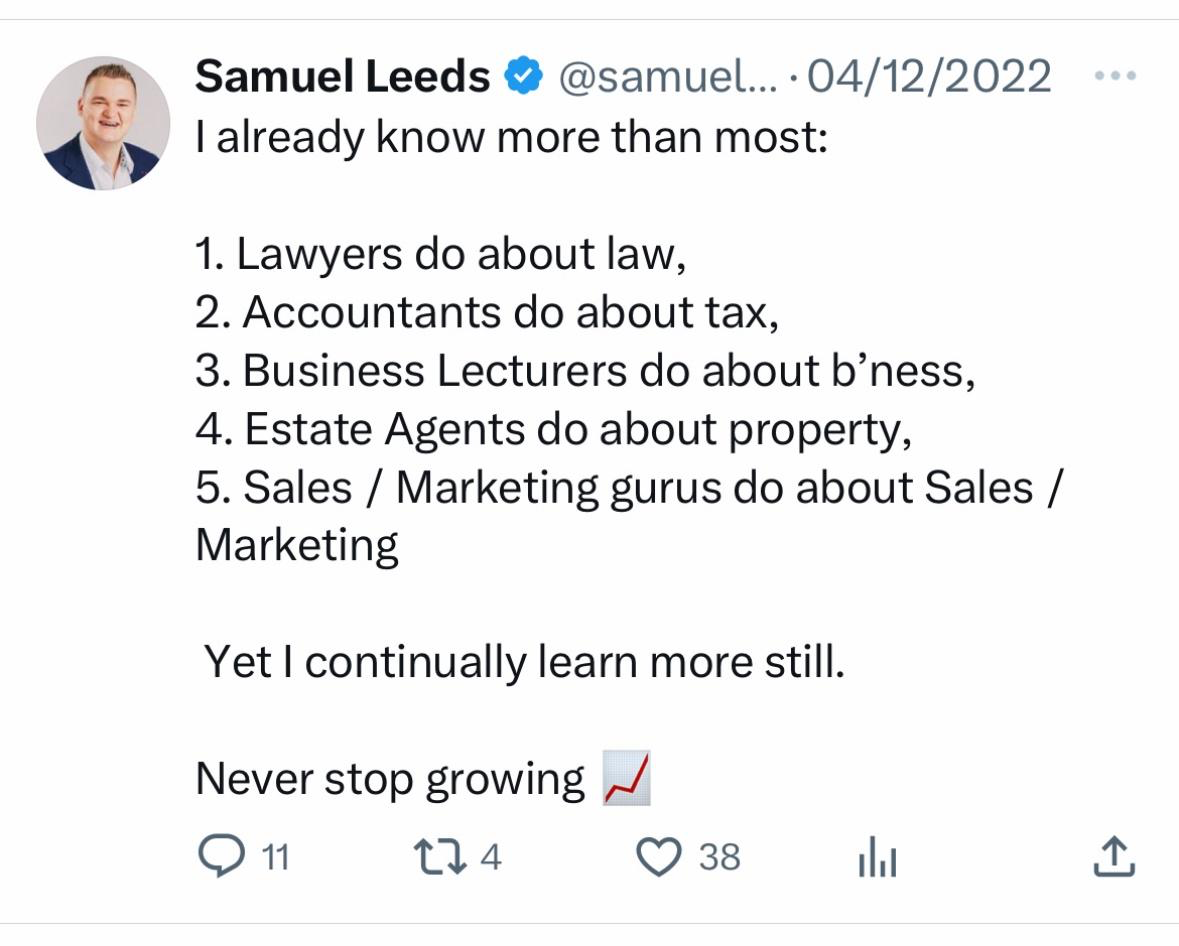

The Samuel Leeds course

Samuel Leeds markets a course on how to “protect your wealth and legally avoid property taxes”.

It costs £995. That’s a lot of money for generalised advice that doesn’t relate to your particular circumstances – it’s unlikely there’s anything here that couldn’t be found free on the internet. And if the course reflects Samuel Leeds’ view of “tax loopholes” then we expect that much of it will be wrong.

The money would be better spent on specific advice from a qualified adviser.

What if you’ve used any of these schemes?

If you’ve used any of the “strategies” outlined above then we’d recommend that you speak to a qualified tax adviser as soon as you can. That usually means from someone at a regulated firm (accounting firm or law firm), and/or with a tax qualification such as STEP, or a Chartered Institute of Taxation or Association of Tax Technicians qualification.

Don’t speak to HMRC until you’ve received professional advice. Keep copies of all the material you relied on (videos, course notes, messages) and a timeline of what you did and when – your adviser will need it.

Conspiracy theories

Mr Leeds promotes his tax strategies and courses using false conspiracy theories about tax and HMRC.

This video claims that the World Economic Forum has a “plan to seize your home” and wants to “own everything and take your house in the process”. This is a conspiracy theory based on a misreading of a short 2016 essay by a Danish MP: “Welcome to 2030: I own nothing, have no privacy, and life has never been better“. It was a speculative thought experiment by a single author – not a policy proposal, plan, or WEF programme. The WEF itself has explicitly stated that the article does not reflect its agenda and that (rather obviously) it does not advocate abolishing private property.

Another video is entitled “HMRC WILL come for YOU in 2026”, and claims that the “new”16 procedure for “direct recovery of debts” means that, if HMRC think you owe them money, they can simply take the money from your bank account. That is not correct: the procedure applies only to debts that are already due and legally established – typically after HMRC has undertaken an enquiry, closed the enquiry concluding that the taxpayer owes tax, and the taxpayer has either not appealed, or any appeal has been concluded. It doesn’t bypass enquiries or disputes; it comes after them. There’s an excellent overview in this House of Commons Library briefing. The video concludes by promoting Mr Leeds’ other video which he says will help you learn ways to potentially bring your tax bill down to zero.

We don’t know why Mr Leeds promotes conspiracy theories that just a few minutes’ research reveals have no factual basis.

Samuel Leeds’ response

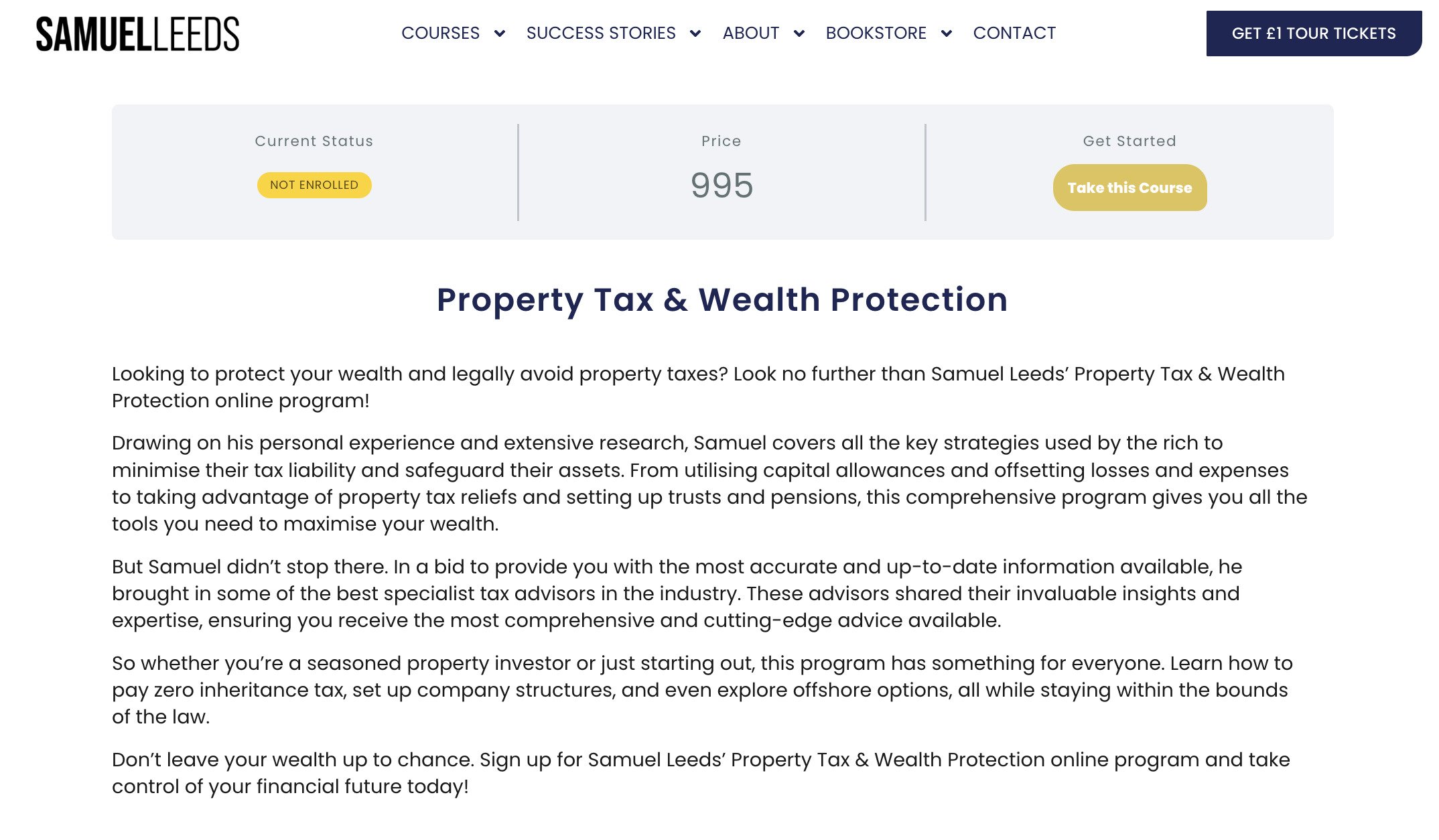

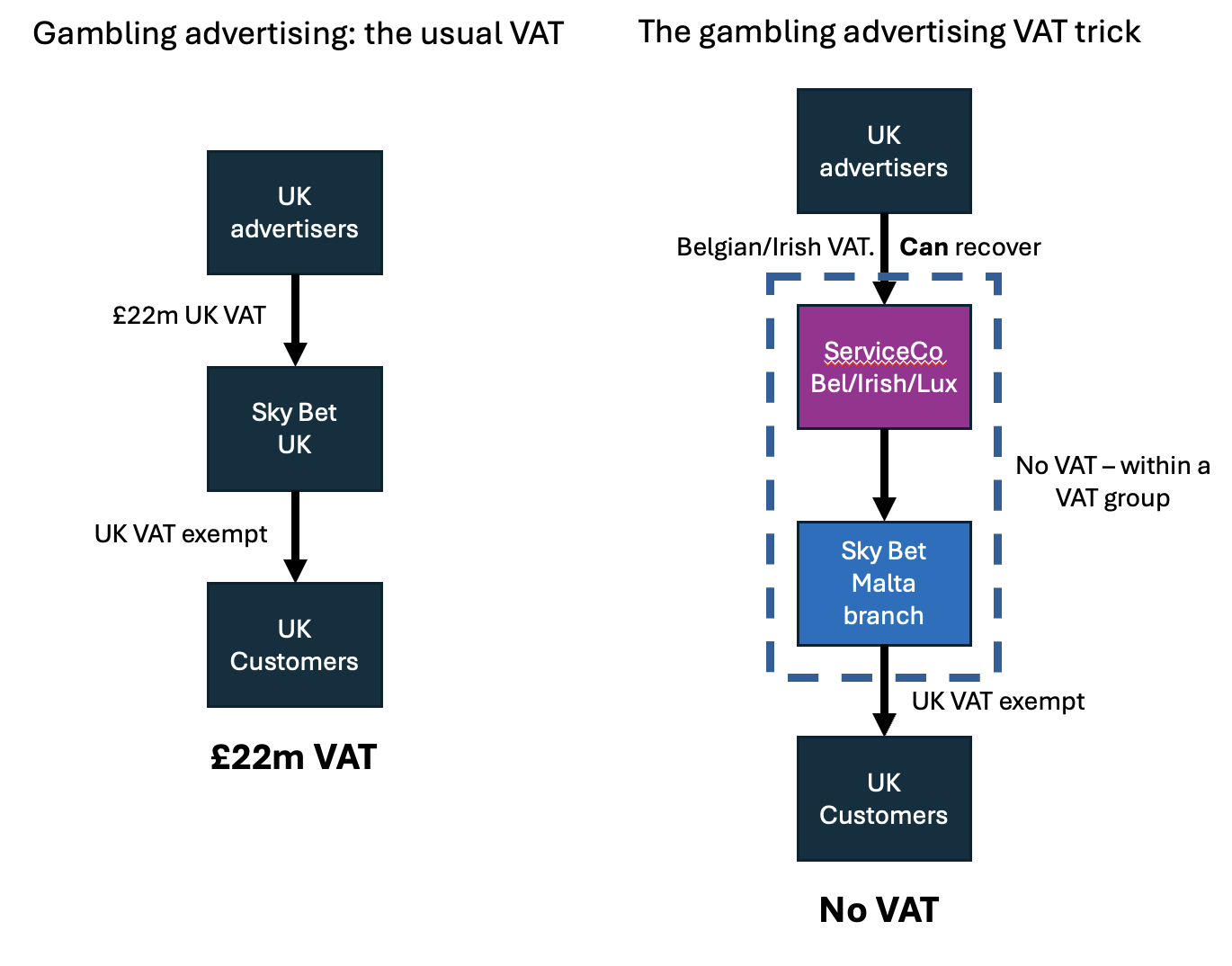

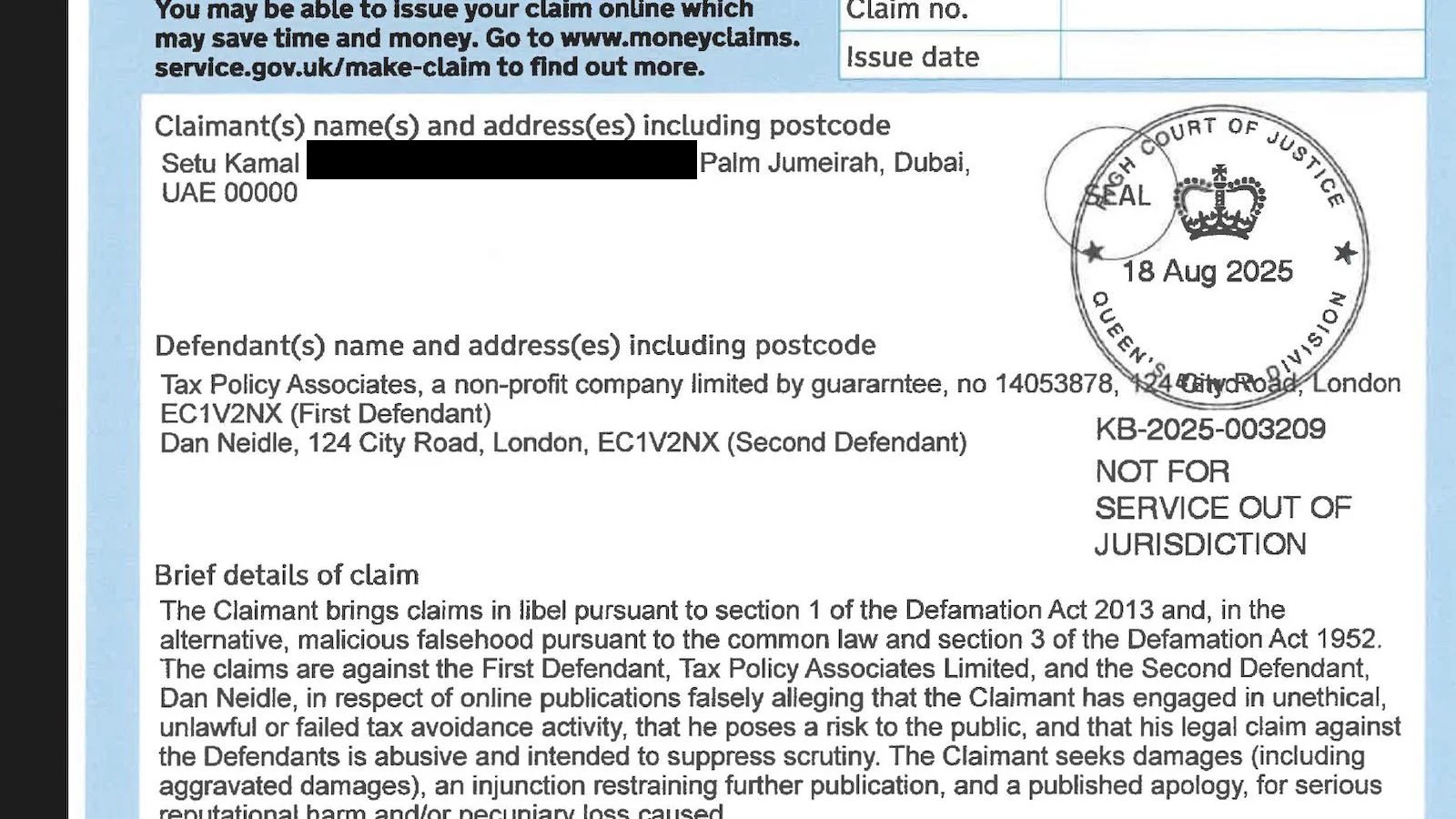

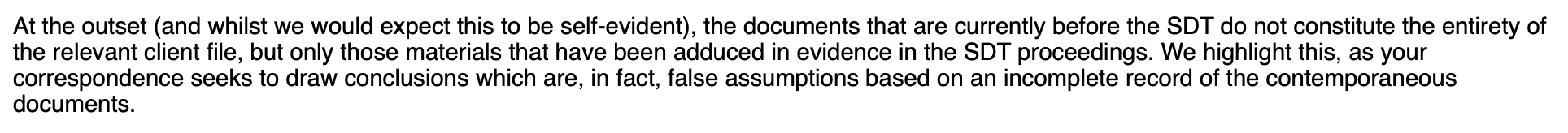

Tax adviser Rowan Morrow-McDade criticised Mr Leeds on LinkedIn for sharing incorrect property tax advice:

Mr Leeds initially tried to defend his claims. As John Shallcross, a stamp duty land tax specialist, pointed out, Mr Leeds was citing cases he didn’t understand.

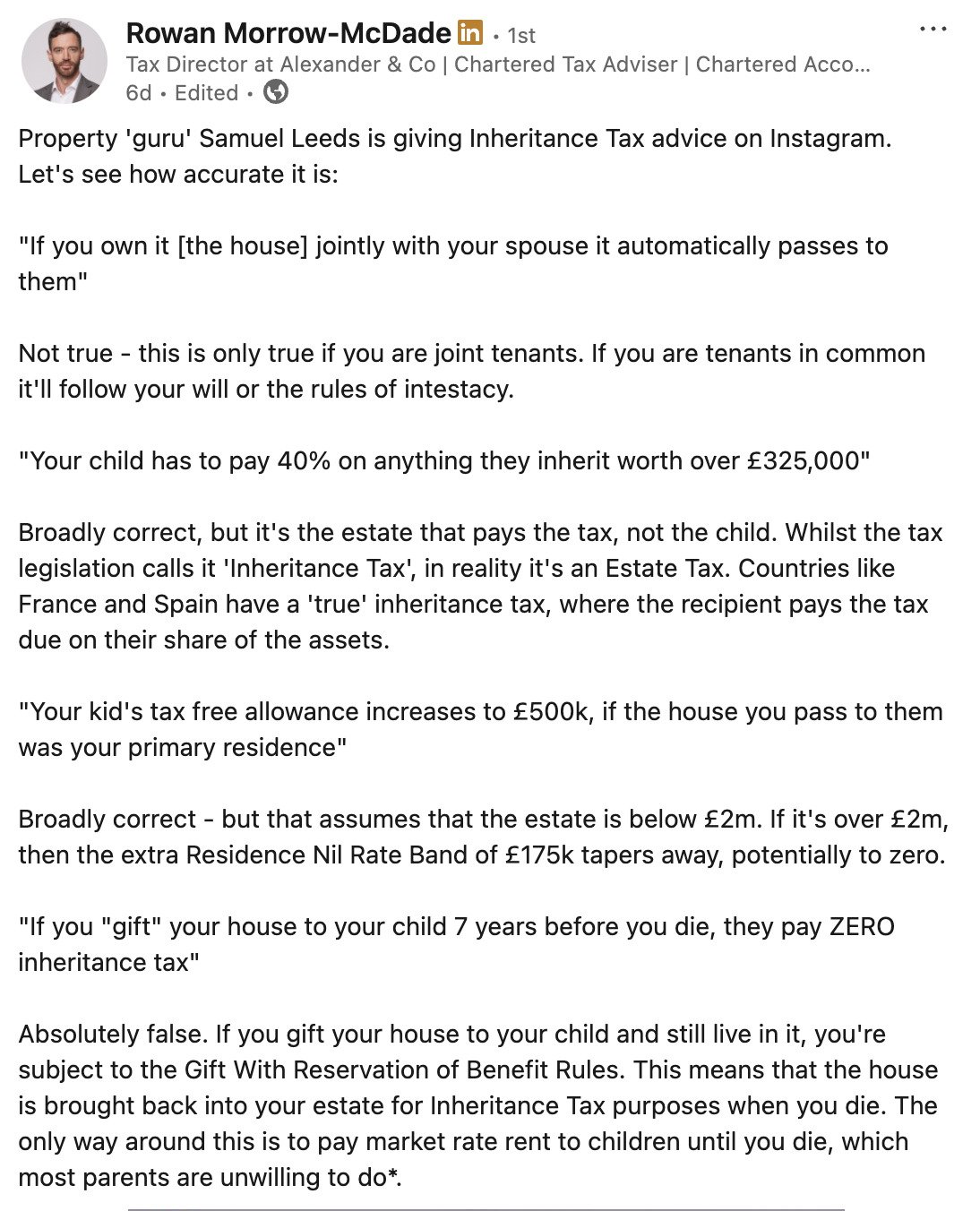

In response, Mr Leeds accused tax advisers of “gatekeeping”:

We asked Mr Leeds for comment before publishing this story and asked, specifically, if he really had – as he claims – “flipped” properties multiple times and claimed the CGT main residence exemption. He refused to comment, instead giving us a generic denial:

The post you have shared describes a high level example of a principal private residence strategy. It is not a statement that repeated property trading would be exempt from tax regardless of facts or intention.

I have not unlawfully failed to pay capital gains tax. Any suggestion otherwise is incorrect.

I do not provide personalised tax advice and I do not advise people to engage in unlawful behaviour. As you know principal private residence relief depends on individual circumstances and intention which cannot be determined from a short social media post.

If you intend to allege unlawful conduct by me personally you will need to provide evidence to support that claim. Otherwise I expect that allegation to be removed from any publication.

I will respond publicly once your article is published.

The full email exchange is here.

The problem with Mr Leeds’ “high level example of a principal private residence strategy” is that the strategy simply does not work. If you intend to acquire, refurbish and sell properties, then case law and legislation mean that the main residence exemption will not apply. It’s not about the detail and intention – the basic concept is a failure.

If Mr Leeds’ claim is true, and he really did acquire, refurbish and sell multiple properties, then in our view he should have paid capital gains tax or income tax. If he didn’t, then that suggests tax was underpaid – it’s “failed tax avoidance“. Of course it’s also possible that Mr Leeds exaggerated, and he either hasn’t used this approach at all, or he has exaggerated (for example, because it wasn’t a deliberate strategy at the time, and he didn’t intend to sell the property). He’s certainly exaggerating when he claims “the rich” use this strategy – it goes without saying that “the rich” do not in fact repeatedly move into unliveable houses to save tax.

Mr Leeds repeatedly says he’s not qualified to give tax advice and viewers of his videos should speak to an accountant. That’s no excuse for proposing “strategies” that don’t work. It’s also undercut when he says things like this:

This level of confidence is dangerous – particularly when his courses seem targeted at people on low incomes who may not be able to afford an accountant.

Our view is simple: it’s deeply irresponsible to market tax “loopholes” that don’t work. Mr Leeds claims to know more about tax than most accountants. Yet the examples above contain repeated, basic errors. If this is his “tax expertise”, readers can draw their own conclusions about the rest of his courses.

Many thanks to K and P for help with the tax analysis, to Rowan Morrow-McDade for his original LinkedIn post, and to John Shallcross for his invaluable assistance with the SDLT aspects of this report.

Videos and images and text © Samuel Leeds and republished here in the public interest and for purposes of criticism and review.

Footnotes

There were similar comments in the Mark Campbell case:

“Having considered all of the evidence, cumulatively, I find that the Appellant did not intend that any of the properties would be his main residence. This is because the evidence before me does not support a finding that there was any degree of permanence, continuity or expectation of continuity in relation to any of the properties. In reaching these findings, I have considered the nature, quality, length and circumstances of any occupation relied on.“ ↩︎

Or possibly a “venture in the nature of a trade“, even if not repeated. ↩︎

In Ives, it was not – there were successive purchases, renovations and sales, but the Tribunal accepted evidence that each purchase was intended to be a permanent residence, but for various reasons Mr Ives later had to move house. ↩︎

The usual HMRC practice is to run trading and section 224(3) arguments in the alternative. ↩︎

And note that the reference to “income tax” here is also wrong – possibly Mr Leeds is conflating the trading rules with section 224(3). ↩︎

Subject to exemptions like business property relief, which in principle applies to shares in a trading company. However such exemptions also apply if the assets/shares are held directly; the trust is not creating the exemption. ↩︎

One particular variant that’s sometimes marketed uses the employee benefit trust rules, as EBTs in principle aren’t subject to inheritance tax. However EBTs are intended for employee remuneration; using them primarily to benefit participators/owners attracts intense HMRC scrutiny and specific anti-avoidance rules. We are not suggesting Mr Leeds uses an EBT. ↩︎

In principle you can gift your house to your kids and then continue living in it, with your kids charging you a market rent; that’s often an undesirable outcome, particularly as the rent will be taxable for your children. ↩︎

However you did give the house away as far as capital gains tax is concerned, meaning that this “strategy” doesn’t save inheritance tax, but can result in an increased capital gains tax bill for your children. ↩︎

And if you use a letting agent they’re required to withhold tax when paying you, unless you obtain approval from HMRC to be paid without withholding and then file a self assessment. ↩︎

i.e. because he’s claiming the salaries are tax-deductible for the company, but below the personal allowance and so not taxable for the kids. ↩︎

The tax in question is “stamp duty land tax” (SDLT). It’s almost always called “stamp duty” in popular discourse, but “stamp duty” is actually a completely different tax. With apologies to tax advisers, we’re going to use the term “stamp duty” in this article to avoid confusing laypeople. ↩︎

The video was posted in March 2025. The source to the YouTube page includes the metadata: “itemprop=”datePublished” content=”2025-03-09T10:00:25-07:00″. ↩︎

This reflects case law. Five months earlier, the Mudan case had confirmed that the scope of the uninhabitable exemption is very limited (and this was then upheld by the Court of Appeal in June 2025). ↩︎

Mudan is clear that you can’t form a judgment based on a “snapshot”. ↩︎

It’s not new. Direct recovery of debts came into force in 2015, was paused as a result of Covid, and resumed in 2025. ↩︎

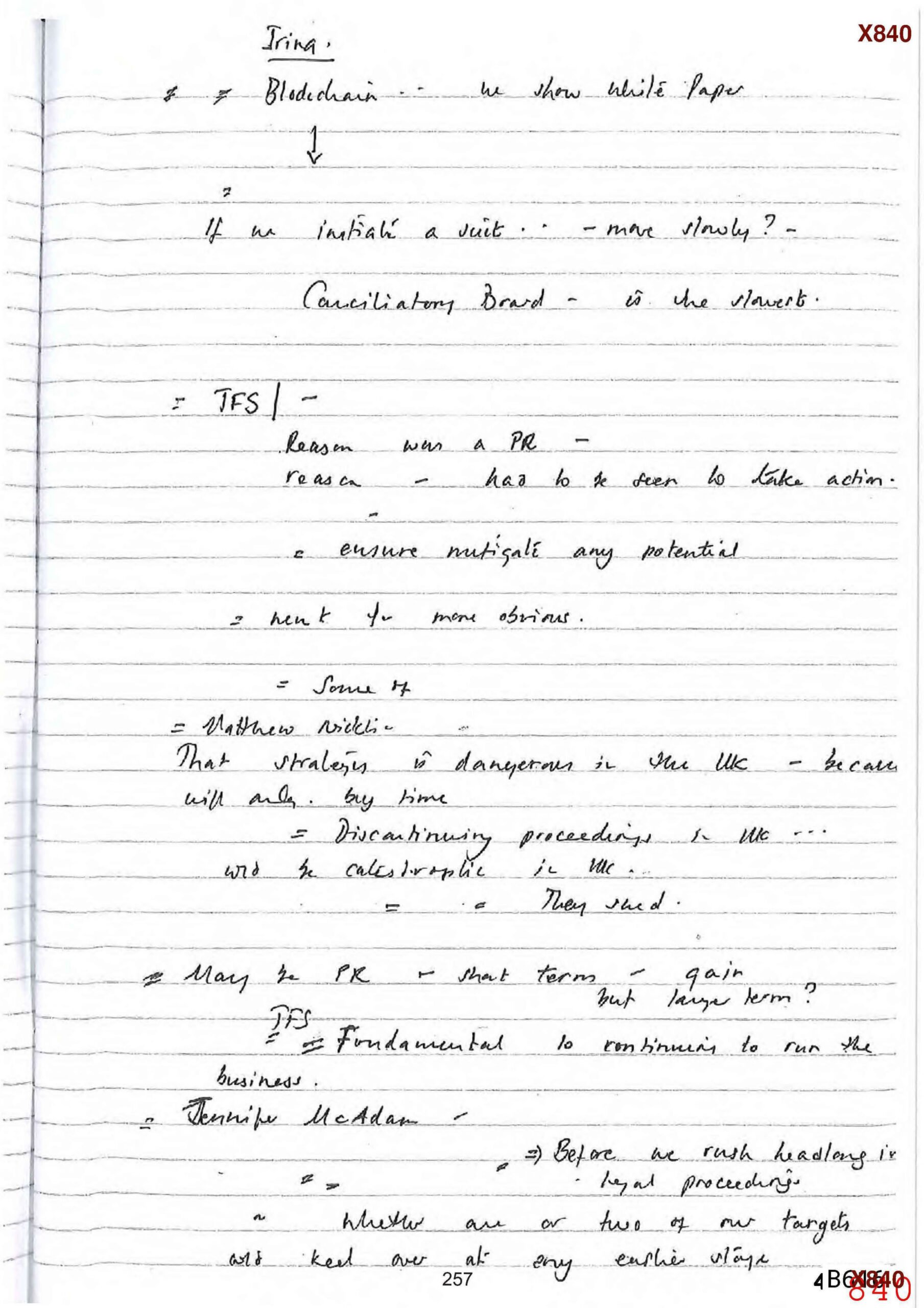

![(3) [F7 sections 223 and 223B] shall not apply in relation to a gain if the acquisition of,

or of the interest in, the dwelling-house or the part of a dwelling-house was made

wholly or partly for the purpose of realising a gain from the disposal of it, and shall

not apply in relation to a gain so far as attributable to any expenditure which was

incurred after the beginning of the period of ownership and was incurred wholly or

partly for the purpose of realising a gain from the disposal.](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/upload_5b8222f9-5a9b-47d8-bd77-1389fb3a9e84.jpg)

![Oy Samuel Leeds @ t Follow ] vo

"tf @samuel leeds

At the moment, 92% of my real estate is held in the Uk.

My 2030, my goal is for that number to be 60%

As much as | love UK real estate, it’s important to

diversify into different markets.

| have a trust set up to hold them to pass generational

wealth, today I’ve been on multiple viewings and been

putting forward embarrassingly low offers on prime luxury

properties.

Don’t wait to buy real estate, buy real estate and wait }](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/1720852696714.jpeg)

![Rowan Morrow-McDade {) - 1st

Tax Director at Alexander & Co | Chartered Tax Adviser | Chartered Acco...

PR 30- Edited - ©

"Guru" Samuel Leeds is now sharing property tax advice on Instagram. Let's see

how it stacks up:

"Buy an unlivable house for about £150k that's been empty for over two years.

Because it's unhabitable, you pay no Stamp Duty”

Completely incorrect. The recent Court of Appeal decision of Mudan [2025]

showed that remedial work - however extensive - does not in itself make a

property non-residential. The courts consider whether a building retains the

essential characteristics of a residential property. Only in very extreme cases of

structural disrepair will a property be considered not a "dwelling" for SDLT

purposes.*

"Only pay 5% VAT on refurb costs as the property has been uninhabited for 2+

years"

This is in fact true - but it only relates to structural repairs/renovations. It doesn't

apply to things like carpets or fitted bedroom furniture, or landscaping the

garden.

"Spend around £50k, fixing it up while making it your primary residence. Sell

once finished for around £100k profit, tax free because it's your main residence"

No - wrong again. The Capital Gains Tax exemption for main residences “shall

not apply in relation to a gain if the acquisition of... the dwelling-house ...was

made wholly or partly for the purpose of realising a gain from the disposal of

it"r*

So if HMRC argue that you bought the house to make a profit from it, they will

deny the exemption, giving you a 24% Capital Gains Tax bill on sale. In a worst

case (see the title of Samuel's post "How the rich flip houses") then HMRC can

tax it as trading income at up to 47%.](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/upload_9e3d3791-6701-4ff8-8952-0948acc49340.jpg)

![328 Arrangements

(1) Aperson commits an offence if he enters into or becomes concerned in an arrangement which he knows or suspects

facilitates (by whatever means) the acquisition, retention, use or control of criminal property by or on behalf of another

person.

(2) Buta person does not commit such an offence if—

(a) he makes an authorised disclosure under section 338 and (if the disclosure is made before he does the act

mentioned in subsection (1)) he has the appropriate consent;

(b) he intended to make such a disclosure but had a reasonable excuse for not doing so;

(c) the act he does is done in carrying out a function he has relating to the enforcement of any provision of this

Act or of any other enactment relating to criminal conduct or benefit from criminal conduct.

[Fi (3) Nor does a person commit an offence under subsection (1) if—

(a) he knows, or believes on reasonable grounds, that the relevant criminal conduct occurred in a particular

country or territory outside the United Kingdom, and

(b) the relevant criminal conduct—

(i) was not, at the time it occurred, unlawful under the criminal law then applying in that country or

territory, and

(ii) is not of a description prescribed by an order made by the Secretary of State.

(4) In subsection (3) “the relevant criminal conduct” is the criminal conduct by reference to which the property concerned is

criminal property. ]](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-11-at-19.58.50.png)

![329Acquisition, use and possession (1)A person commits an offence if he— (a)acquires criminal property; (b)uses criminal property; (c)has possession of criminal property. (2)But a person does not commit such an offence if— (a)he makes an authorised disclosure under section 338 and (if the disclosure is made before he does the act mentioned in subsection (1)) he has the appropriate consent; (b)he intended to make such a disclosure but had a reasonable excuse for not doing so; (c)he acquired or used or had possession of the property for adequate consideration; (d)the act he does is done in carrying out a function he has relating to the enforcement of any provision of this Act or of any other enactment relating to criminal conduct or benefit from criminal conduct. [F1(2A)Nor does a person commit an offence under subsection (1) if— (a)he knows, or believes on reasonable grounds, that the relevant criminal conduct occurred in a particular country or territory outside the United Kingdom, and (b)the relevant criminal conduct— (i)was not, at the time it occurred, unlawful under the criminal law then applying in that country or territory, and (ii)is not of a description prescribed by an order made by the Secretary of State. (2B)In subsection (2A) “the relevant criminal conduct” is the criminal conduct by reference to which the property concerned is criminal property.]](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-11-at-22.25.45.png)

![By this application, the Respondent seeks disclosure of the content of the initial recommendation of Dr Sam Jones, the Senior Investigation Officer who was assigned the Respondent’s case and who produced the notice referring the Respondent to the Tribunal. Dr Jones had previously indicated to the Respondent and her firm, by an email dated 12 July 2023, that she had made a recommendation on the outcome of the investigation, and intended to provide an update the following month “to bring this matter to a conclusion” [X1037]. An apparent intervention by senior management prevented the notification of any decision by Dr Jones until 8 February 2024, when she served a very wide-ranging notice of referral [X4-X32], most of the allegations in which have since been abandoned by the Applicant.

5.

The Respondent has inferred that Dr Jones’ original recommendation was to close the investigation and has asked the Applicant to disclose it. The Applicant has refused disclosure and otherwise refused to confirm or deny the inference drawn by the Respondent. Accordingly, the Respondent seeks an order for disclosure.](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Untitled-1.jpg)