It is a national scandal that teachers, doctors and others earning fairly ordinary salaries can face marginal tax rates of more than 60%, and sometimes approaching 80%. It’s inequitable and holds back growth. Rachel Reeves should commit to ending these anomalies.

This Government was elected on a platform of kickstarting economic growth. It has a large majority, and four or five years until the next election. It’s a rare chance for real pro-growth tax reform. That’s all the more necessary if we are going to see tax rises.

We’ll be presenting a series of tax reform proposals over the coming weeks. This is the fifth – you can see the complete set here.

Marginal rates

The “marginal rate” is the percentage of tax you’ll pay on your next £1 of income. It therefore affects your incentive to earn that £1.1Everything interesting happens at the margin. For more on why that is, and some international context, there’s a fascinating paper by the Tax Foundation here.

If you doubt that, imagine that you pay tax at 20% on your £30k income, but the next £1 you earn will be taxed at a marginal rate of 100%. Would you work extra hours for zero after-tax pay? I think most people would not. The overall tax you pay would only be a bit over 20%, but your decision to work more hours is affected by your after-tax pay for those hours.

That seems a silly example (although we can find worse ones in our own tax system – see below). But a marginal rate below 100% will also change your incentives.

Perhaps you are only just managing to afford childcare, and every hour you earn increases your childcare costs? A marginal rate of 70% might mean your take-home pay is less than that childcare cost.

Or it may just be that you value your own time so that, if your take-home pay from working additional hours drops below a certain point, it’s not worth it to you.

Marginal rates – a normal example

In the current, 2024/25 tax year, combined income tax and national insurance rates for an employee look like this:2Ignoring Scotland for the moment; we’ll get to the Scottish rates later.

- No tax on incomes below the £12,570 personal allowance.

- £12,570 to £50,270 – a combined income tax and employee national insurance rate of 28%

- £50,271 to £125,140 – a combined rate of 42%3That’s the headline rate – the actual rate is different… for which see further below.

- Above £125,140 – a combined rate of 47%.

It’s important to realise that the different tax brackets only apply to income in that bracket. If you earn £50,271 you’re in the higher tax bracket, but you only pay 42% tax on £1. You still pay 28% tax on everything you earned before above the personal allowance. This is unfortunately not very well understood.

Imagine Bob is an employee earning £12,569. None of his income is taxed. Bob has the opportunity4Perhaps he is self-employed and chooses which clients/work he takes on. Perhaps he is employed, and can choose how much overtime to work, or whether to accept a promotion. Perhaps he is going back to work after time spent looking after young children. Many people have the ability to work additional hours if they wish. to earn an additional £1,000, putting him in the 28% tax bracket.5Strictly that doesn’t exist – you’re paying basic rate tax plus Class 1 employee national insurance contributions. But realistically this amounts to 28% tax. I’m going to count income tax and national insurance as if they’re one tax throughout this article.

There are three ways we could describe Bob’s position after earning that £1,000.

- The applicable headline rate. Bob is a basic rate 28% taxpayer.

- The overall effective tax rate. This is the total tax paid divided by Bob’s income. Total tax paid = £1,000 x 28% = £280. Income = £13,570. So effective tax rate is 280/13570 = about 2%.

- The marginal rate – the percentage tax you’re paying on that new £1,000. This is 280/1000 = 28%.

Each of these has their uses.

The first figure is simple.

The second is useful for assessing how much tax Bob pays overall. If a political party proposed a sweeping set of tax reforms, Bob would be very interested in the impact on his effective rate.

But the third – the marginal rate – is important, because it affects Bob’s incentive to earn the additional pound. Right now it’s the same as the headline rate – but that’s not always the case…

Marginal rates – the problem

Jane is earning £60k and claiming child benefit for three children. That’s worth £3,094.

She’s now in the 42% tax band.6Strictly that doesn’t exist – she’s paying 40% higher rate tax plus 2% Class 1 employee national insurance contributions. Realistically this is 42% tax. Jane still pays basic rate tax for her income between £12,570 and £50,270, but now pays 42% tax for everything over that. So her total tax bill is (50270 – 12570) * 28% + (60000-50270) * 42% = £14,643 and Jane takes home £45,357.

Jane is thinking of working a few more hours to earn another £1,000. She’s in the higher tax band – so in a sane world she’d expect another £420 of tax, and a marginal rate of 42%.

But that is not the result. Once Jane’s income hits £60,200, the “High Income Child Benefit Charge” (introduced by George Osborne) starts to apply to claw back her child benefit – 1% for every £200 of earnings.

So that £1,000 of additional earnings costs Jane HICBC of £154.70, on top of the £420 of “normal” tax. A total of £565.

So how do we describe Jane’s position after earning that £1,000?

- The applicable headline rate. Jane is a higher rate 42% taxpayer.

- The overall effective tax rate – the total tax paid divided by Jane’s income. That’s 15207/61000 = about 25%.

- The marginal rate – the tax Jane is paying on that new £1,000. This is 56.5% – and we will have the same result for all incomes between £60k and £80k. 7Note that the marginal rate will vary depending on how we calculate it, and the size of the “perturbation” we calculate the marginal rate over. Most textbooks define the marginal rate as the % tax on the next pound/dollar of income. Say that we looked at the tax Jane paid on £60,199 of income – that would be £14,726. A £1 pay rise takes her to £60,200, and tips her into the HICBC – she now pays £0.42 more higher rate tax, plus an additional HICBC charge of 1% of your child benefit – £30.94 (assuming you have three kids). So the marginal rate is 100 * (£31.63/£1) = 3,163%. This is not very meaningful, as nobody’s incentives are going to be affected by the consequence of a £1 pay rise. It also creates the silly result that the marginal rate on her next £1 pay rise will be 42%, because the HICBC won’t increase until she gets to £60,400. So it’s better to use a more realistic figure like £1,000. The practical consequence is that the 56.5% figure isn’t *the* correct answer, but it’s a sensible and useful one, and it’s important to check that weird marginal rates aren’t just an artifact of the chosen perturbation. Our charting code uses a £100 perturbation for convenience, but then “smooths” the HICBC formula so the marginal rate doesn’t leap up and down.

As I mentioned at the start, there can be practical reasons for people to turn down work if the marginal tax rate gets too high – but there are also psychological factors. For many people, 50% feels like a high rate.

Charting the effect

We can chart Jane’s marginal rate for each pound of income she could earn. Incomes along the bottom, marginal rate along the top:

You can see the HICBC as the “tower” between £60k and £80k, which should be a smooth 42% plateau. Instead it hits 57%. (I’m hiding what happens after £100k)

The HICBC is a gimmick which enabled George Osborne to somewhat-surreptitiously raise tax on people on high incomes without raising the tax rate itself.

It’s a really bad policy:

- It means that Jane pays a higher marginal rate rate than someone earning £90k, or indeed £900k. Where’s the logic in that?

- The way in which HICBC works creates a nasty trap for the unwary, with thousands of people accidentally incurring HMRC penalties.

The politics are nice and intuitive – surely it’s not right for people on high incomes to receive child benefit? But the reality is that this logic inexorably leads to a high marginal rate, and a cumbersome and sometimes unjust collection mechanism.

Can it get worse?

Very much worse.

George Osborne’s HICBC was copying a trick invented by Gordon Brown to clawback the personal allowance for people earning £100k.

Again, the politics are nice, but the consequences are a mess.

If Jane starts earning between £100k and £125k then she faces a marginal tax rate of 62%. It then drops to 47% from £125k. Her marginal rate chart looks like this:

Needless to say, 62% is a very high rate.

The graduate tax

And if Jane has a student loan, that will add on 9% to the marginal rate, meaning that her marginal rate chart now looks like this:

The student loan system behaves like a crude graduate tax so that, between £100k and £125k, Jane’s marginal rate reaches 71%.

The anomalous marginal rates

Student loan repayments, personal allowance tapering and child benefit clawback all result in high marginal rates. But the rates are at least within “normal” bounds – they don’t exceed 100%.

There are points at which the marginal rate sails way over 100%, meaning that you are actually worse off after a pay rise. This occurs when tax benefits/allowances have a “cliff edge” after which they disappear completely:

- The £1,000 personal savings allowance drops to £500 once you hit the higher rate band, and to zero once you hit the additional rate band.8The £5,000 starting rate for savings tapers out, but slowly, and so it just somewhat increases the marginal rate – it’s also less relevant for most people.

- The marriage allowance lets a non-working spouse transfer £1,260 of their unused personal allowance to their partner, if they’re earning less than the £50,270 higher rate threshold. So it’s worth £252 – and it disappears once the higher rate band is hit.

These are irrational rules, but the tax at stake is small, and so the high marginal rate is limited to a small range of incomes. The significance is limited.

A much more significant cliff-edge effect results from the childcare schemes created by the previous Government. These provide generous subsidies that are removed suddenly when your wage hits £100,000. That creates a marginal rate that is truly anomalous – so high it is hard to calculate.

The childcare support scheme for parents with children under 3 could be worth £10,000 per child for parents living in London. And it vanishes once one parent’s earnings hit £100k. Here’s what that does to the marginal tax rate:9The chart is for a single earner, but if they have a partner, the partner would also need to be earning at least £8,668 (the national minimum wage for 16 hours a week)

The 20,000% spike at £100,000 is absolutely not a joke – someone earning £99,999.99 with two children under three in London will lose an immediate £20k if they earn a penny more.10The 20,000% figure is a consequence of the code that produces the chart incrementing the gross salary by £100 in each step. It would be a mere 2,000% if we used the same £1,000 perturbation as above. Two million percent if we used the conventional £1 perturbation. Or two hundred million percent if we looked at the one penny increase. And the negative spike at £8,668 is because it’s at that point you qualify for the scheme – you have a huge negative marginal tax rate (which has the potential to create obvious distortions of its own).

The practical effect is clearer if we plot gross vs net income:

After-tax income drops calamitously at £100k, and doesn’t recover to where it was until the gross salary hits £145k.

This is ignoring the pre-existing tax-free childcare scheme, which also vanishes at £100k. The amounts are less (usually under c£7k/child) so the curve would look less dramatic. However, as the scheme applies to children under 11, taxpayers feel these effects for many more years.

Marginal rates for high earners

If Jane started earning beyond £145k, all of these problems go away, and she has a nice straightforward marginal rate of 47% forever.11Ignoring pensions, which create a marginal rate problem all of their own…

What kind of tax system creates complexities and high marginal rates for people earning £60-125k, and simplicity and lower marginal rates for people earning more than £125k?

The complete picture

Here’s an interactive chart showing all the UK and Scottish marginal rates. You can click on the legend at the bottom to see the effect of child benefit clawback and student loans. Or you can view in fullscreen here.12The code and underlying data are available here.

You’ll see that if you are a recent graduate living in Scotland with three children under 18, between £100k and £125k you face a marginal rate of 78.5%.13Note that the gap between the Scottish and UK marginal rates is much higher than the gap between statutory rates. The HICBC and personal allowance tapers have a bigger effect on higher rates, and so magnify the difference.

The chart doesn’t include marriage allowance, childcare subsidies and the other extremely anomalous marginal rates, as the rates are so high that they make the chart unreadable.

The effect

We’ve received many reports saying that high marginal rates affecting senior doctors/consultants are an important factor in the NHS’s current staffing problems – exacerbated by the fact that the starting salary for a full time consultant is just under £100,000.

But it’s important not to just focus on the impact on jobs that we might think are of particular societal importance.

It’s also problematic if an accountant, estate agent or telephone sanitiser turns away work because of high marginal rates – it represents lost economic growth and lost tax revenue.14Particularly when the economy is running at very little spare capacity; it would be different if there was high unemployment/plenty of spare capacity, because the work that was turned away would (at least in theory, in the long term) be undertaken by others It also makes people miserable.

Sometimes people take the work, but use salary sacrifice or additional pension contributions so their taxable income doesn’t hit the threshold. But that doesn’t work for everyone; sometimes they’ve hit the pensions allowance; sometimes it doesn’t always make sense to work harder now, for money that they can’t touch for years.

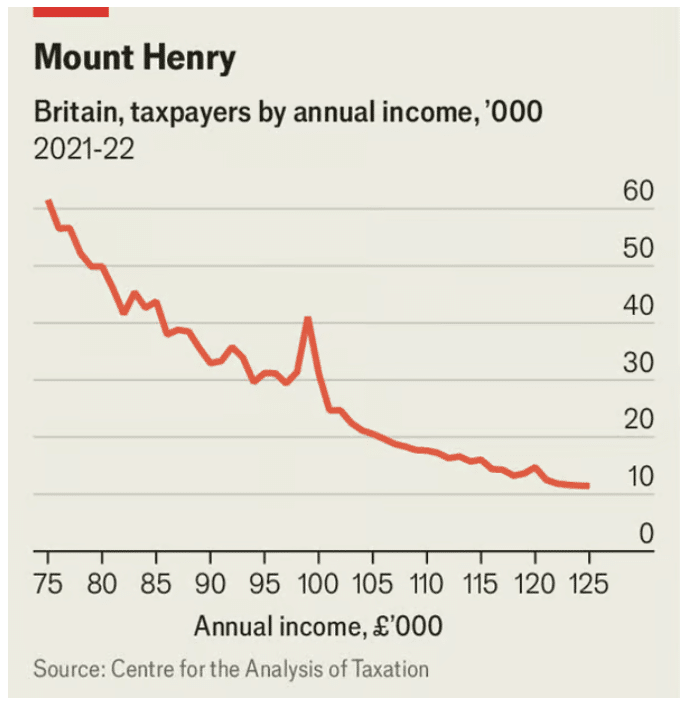

We can see the effect in this chart from the Economist, based on data from the Centre for the Analysis of Taxation:

That cliff at the £100k point is people holding back their earnings so they don’t hit the £100k marginal rates. That represents a loss of working hours to the public and private sectors and a macroeconomic impact on the UK as a whole. Quite how large an impact is an interesting question, which I hope someone looks at.

What’s the solution?

These problems are getting worse over time, as fiscal drag takes more and more people into the thresholds that trigger these high marginal rates.

When Gordon Brown introduced the personal allowance taper in 2009, only 2% of taxpayers earned £100,000; by 2025/26 over 5% of taxpayers will. When George Osborne introduced child benefit clawback a year later, only 8% if taxpayers earned £50,000; by 2025/26 over 20% of taxpayers will (which is likely what motivated Jeremy Hunt to increase the threshold to £60,000).15Data from the HMRC percentile stats, uprated for post-2022 inflation.

This creates a double problem. First, the economic distortions created by the high marginal rates start to impact into mainstream occupations (doctors, teachers). Second, the revenues raised by the marginal rates are now so great that they become hard to repeal.

Ending the high marginal rates in one Budget is, therefore, not realistic – particularly in the current fiscal environment. The cost of making child benefit, the personal allowance, and childcare subsidies universal, would be expensive (somewhere between £5-10bn, depending on your assumptions). The obvious way of funding this – increasing income tax on high earners, appears to have been ruled out.

We would suggest four modest steps:

- An acknowledgment that the top marginal rates are damagingly high, and that the Government will take steps to reduce them when economic circumstances permit.

- Some immediate easing of the worst effects, at minimal cost to the Exchequer, for example by smoothing out the personal allowance taper over a longer stretch of income, therefore reducing the top marginal rate.

- A commitment to uprate the thresholds for the HICBC, personal allowance clawback and childcare subsidy in line with earnings growth.

- A commitment that no steps will be taken to make the high marginal rates worse, or create new ones.

- A new rule that Budgets will be accompanied by an OBS scoring of the highest income tax marginal rates before and after the budget.

There’s a coherent political case for people on high incomes paying higher tax (whether we agree with it or not). There is no coherent case for people earning £60k, or £100k, to pay a higher marginal rate than someone earning £1m. It’s inequitable and economically damaging. Ms Reeves should call time on high marginal rates.

Graphic by DALL-E 3: “A businesswoman climbing a set of stairs labeled with different tax percentages, with the middle step showing 100% and the others smaller %s, representing the different marginal tax rates. Widescreen. Cinematic.”

- 1Everything interesting happens at the margin. For more on why that is, and some international context, there’s a fascinating paper by the Tax Foundation here.

- 2Ignoring Scotland for the moment; we’ll get to the Scottish rates later.

- 3That’s the headline rate – the actual rate is different… for which see further below.

- 4Perhaps he is self-employed and chooses which clients/work he takes on. Perhaps he is employed, and can choose how much overtime to work, or whether to accept a promotion. Perhaps he is going back to work after time spent looking after young children. Many people have the ability to work additional hours if they wish.

- 5Strictly that doesn’t exist – you’re paying basic rate tax plus Class 1 employee national insurance contributions. But realistically this amounts to 28% tax. I’m going to count income tax and national insurance as if they’re one tax throughout this article.

- 6Strictly that doesn’t exist – she’s paying 40% higher rate tax plus 2% Class 1 employee national insurance contributions. Realistically this is 42% tax.

- 7Note that the marginal rate will vary depending on how we calculate it, and the size of the “perturbation” we calculate the marginal rate over. Most textbooks define the marginal rate as the % tax on the next pound/dollar of income. Say that we looked at the tax Jane paid on £60,199 of income – that would be £14,726. A £1 pay rise takes her to £60,200, and tips her into the HICBC – she now pays £0.42 more higher rate tax, plus an additional HICBC charge of 1% of your child benefit – £30.94 (assuming you have three kids). So the marginal rate is 100 * (£31.63/£1) = 3,163%. This is not very meaningful, as nobody’s incentives are going to be affected by the consequence of a £1 pay rise. It also creates the silly result that the marginal rate on her next £1 pay rise will be 42%, because the HICBC won’t increase until she gets to £60,400. So it’s better to use a more realistic figure like £1,000. The practical consequence is that the 56.5% figure isn’t *the* correct answer, but it’s a sensible and useful one, and it’s important to check that weird marginal rates aren’t just an artifact of the chosen perturbation. Our charting code uses a £100 perturbation for convenience, but then “smooths” the HICBC formula so the marginal rate doesn’t leap up and down.

- 8The £5,000 starting rate for savings tapers out, but slowly, and so it just somewhat increases the marginal rate – it’s also less relevant for most people.

- 9The chart is for a single earner, but if they have a partner, the partner would also need to be earning at least £8,668 (the national minimum wage for 16 hours a week)

- 10The 20,000% figure is a consequence of the code that produces the chart incrementing the gross salary by £100 in each step. It would be a mere 2,000% if we used the same £1,000 perturbation as above. Two million percent if we used the conventional £1 perturbation. Or two hundred million percent if we looked at the one penny increase.

- 11Ignoring pensions, which create a marginal rate problem all of their own…

- 12

- 13Note that the gap between the Scottish and UK marginal rates is much higher than the gap between statutory rates. The HICBC and personal allowance tapers have a bigger effect on higher rates, and so magnify the difference.

- 14Particularly when the economy is running at very little spare capacity; it would be different if there was high unemployment/plenty of spare capacity, because the work that was turned away would (at least in theory, in the long term) be undertaken by others

- 15Data from the HMRC percentile stats, uprated for post-2022 inflation.

22 responses to “How to reform income tax: end the high marginal rate scandal”

Good article – it’s clear that these policies and changes were not well thought out – the HICBC and childcare policies are also unfair for single parent households. Is there a reason that the Universal Credit taper isn’t included in this analysis? It must produce a very similar effect.

I’m an engineer. I am reducing my hours to four days per week so as not to have to pay the frankly outrageous 62% tax. Fiscal drag is bringing so many more people into these obscene marginal rates. How can we develop a growing economy when the workforce is not incentivised to work more hours due to these outrageous marginal tax traps? There is something egregious about the government taking 2/3 of your hard work away. I heard that this 62% is one of the highest tax rates in Europe.

Firstly I think your figures for Jane’s child benefit tax are wrong – if the threshold is £60,200, you said her child benefit tax would be £154.70 if her income went from £60,000 to £61,000. But surely it should be 1% of every £200 over £60,200, so 4% of her child benefit, not 5% (£123.76)

Secondly, you sadly never discuss the marginal tax rate implications for landlords of Section 24 and to be balanced you really should. Imagine Janice earns £40k a year from her employment and has three children receiving child benefit of £3,094. She also earns £10k profit from her BTL property after allowable expenses and after her mortgage interest payments of £12,000. If George Osborne had not introduced section 24 her highest marginal tax rate would be 28%, and she would not be impacted by the child benefit charge. She would pay 28% of £27,430 and 20% of £10,000 = £9,680.40 tax.

However the current scenario is worse for Janice than you have described for any other of your hypothetical situations above. In the real world, she still only has £50,000 to pay her tax from. But her tax rate is now calculated upon £62,000 (adding her mortgage interest payments back onto her profit but deducting a 20% tax credit of the mortgage interest amount) plus the child benefit charge on the amount over £60,200.

Her tax bill is still £7,680.40 for her employment income. Her rental income tax is 20% of £10,270 = £2054

Plus 40% of £11,730 = £4692

Total rental income tax of £6746, minus 20% tax credit of £2,400 = £4346.

Higher income child benefit charge of 9% of £3094 = £278.46

That’s a total tax bill of £12,304.86 an increase of £2,624.46 (an increase of 27% from the previous tax bill) thanks to George Osborne with absolutely no change in what Janice has at the end of the day.

This is fundamentally unfair. It would have been much fairer to allow mortgage interest to be deducted as an allowable expense but charge NI on rental profits.

This article is about labour income not investment income. Section 24 is a completely different subject. The punitive consequences of section 24 aren’t an accident- it was a deliberate policy decision to push individual landlords to reduce their leverage or get out of the market. You can agree or disagree with that objective, of course.

Thanks for replying Dan, and of course I understand the reasoning why the policy was devised. That’s not to say that you can argue that the reasoning is both flawed and unfair. The curious way in why property rental businesses are partially taxed as an investment and subject to income tax causes too many anomalies.

Oh, and I realised after writing my comment that the threshold for the child benefit tax charge is from £60,000 not £60,200 which was a bit unclear in your article. Does that mean if you earn £60,100 you aren’t subject to the charge but as soon as you hit £60,200 you have to repay 1% of it?

I should also clarify that the reason why my comment is relevant to this article is the way in which section 24 can impact upon the higher rate child benefit charge, further distorting that marginal tax rate jump

Household taxation? Possibly just for the child benefit and childcare. Tories mentioned this in last budget as a future option.

If people object to share income with partner, then just don’t pay any benefit.

Excellent article, thanks. With the fuss over the winter fuel allowance I have been wondering why not create a taper similar to the HICBC to at least avoid a cliff edge. I expect the answer it is would be too difficult to implement, but no more difficult than something that already exists for younger generations.

If “benefits” ( eg Child benefit, childcare) were not means tested ( ie universal within the cohort universe), but then taxed through SA ( so in effect the cash value of benefits added to pre tax income) wouldn’t that be a reasonable solution? Plus no “ cliff edges”.

In theory yes, but there would be resistance to requiring everyone receiving any form of benefit with an income of over £12,570 to complete self assessment. That shouldn’t be the case, I used to live in Australia where virtually everyone files a manual tax return, and it’s not difficult, but I am a chartered accountant.

I don’t know what the additional numbers needing to complete SA returns would be, but that shouldn’t be unmanageable and it would reduce the bureaucracy and costs associated with managing and policing means testing. The basic SA form isn’t overly complicated ( much less so than form filling for some benefits…) and could be simplified further for those likely to be new to SA.

This article might be seen as a series of arguments all of which are based on the false premise that an allowance or grant withdrawn or tapered down, is a tax increase. It’s in a similar vein to holding that not charging VAT on school fees is a tax break.

Its shaky basis is particularly starkly revealed when your children grow up and no longer qualify you to receive child benefit. Is that change a reduction in your tax rate? The same applies to help with nursery fees. When your child outgrows that entitlement has their parents’ tax position changed?

The same argument applies to interest on Student loans. These are, in most respects, charges made in exchange for the receipt of goods – further education and living expenses – and are not, in the strict sense of the word, taxation.

A friend of mine’s father was a DWP manager and never managed to get his head round the concept that if you can earn a £1 working but at the expense of a £1 paid in benefits then you should stay on benefits. He felt that a £1 earned was a much better £1 than one received via benefits.

A lot of what you argue could be said to be on similar lines. Whatever the rights and wrongs of all the various rates and their impacts, it is clear that benefits have a seriously distorting effect on an economy and how the world of work operates.

The income of someone on benefits is distorted for as long as they receive them and the ending or withdrawal of those benefits is simply a return to what is the reality of their earnings.

This creates a big incentive to work in the black economy whilst still claiming benefits even at rates well below minimum wage. This then distorts the market even further for the honest citizens.

A really bad take.

No this is a reasonable take.

Not claiming income is the expected outcome of these policies.

These policies are effectively genocidal in their outcome if not intentions.

Great stuff. I would like Brown and Osbourne to explain why they approved these cliff edges (I doubt they invented them) and their successors as to why they were not indexed, the answer being it would leave less money for them to spend on white elephants like HS2. Sorry to be cynical and agree there is no easy answer apart from increasing the going rates both on middle and higher incomes, which is politically impossible.

No, Governments could opt to spend less.

And it’s even worse if you are the director of a small company, your earnings are also hit by employer’s NIC giving an effective rate currently 13.8% higher still!

Hopefully this gets some traction with a government who seem to have realised at least some of the problems with cliff edges in the benefit system, given recent announcement of an enquiry into the problems they cause in relation to carer’s allowance.

Once you start factoring in the tapering down of benefits alongside marginal tax rates you end up with a system where you allow people on modest incomes to keep very little of their additional earnings. It is hardly surprising they don’t choose to work extra hours etc.

Hi, you missed a few things:

– Pension taper above £260k

– Employer NI Contribution (which is effectively a tax on labour)

– An additional 6% student loan repayment for Masters (making it 9% + 6% = 15%)

The 62% +7% band is damaging the economy. I know plenty of people that reduce their hours to be below it. Why work a week for the bulk of to be taken, better to take unpaid leave.

I’m one of them. I’ve cut my hours to 80%.