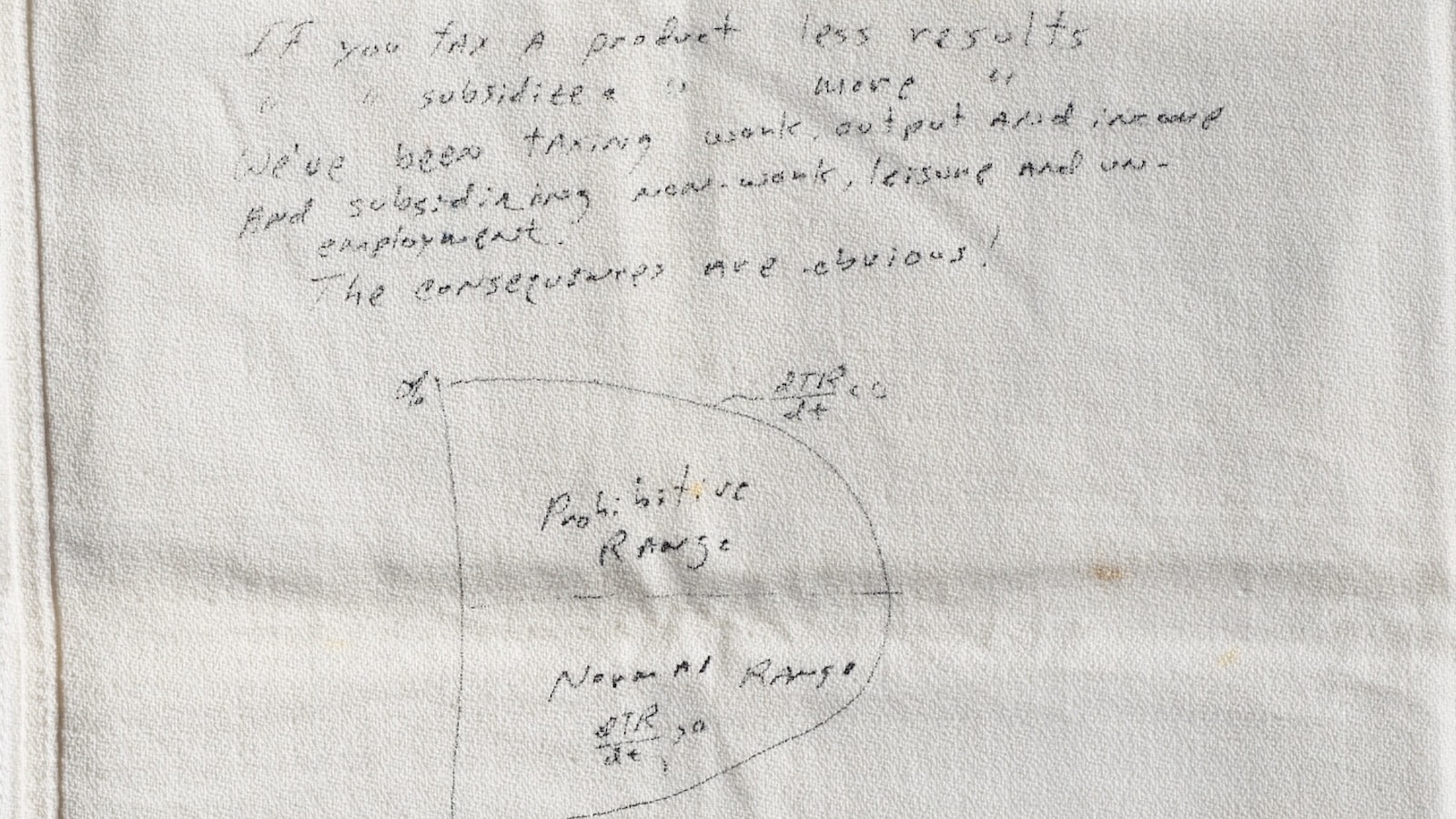

It’s sometimes said that we should go back to the tax system of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, with very high rates of tax on the highest earners. We’ve spoken to people who were around at the time – both tax avoiders and HMRC officials – and looked at the data.

Our conclusion: the apparently progressive tax system of the post-war period was an illusion, with myriad ways for those on high incomes to pay little or no tax. Nobody, whatever their view of taxing the rich, should want to go back to that.

The people who think we should go back to the 1970s

Here’s campaigner Gary Stevenson:

Stevenson is asked if he can point to a period in British history where “massively taxing rich people” has benefited the country. His reply is that his father, born in 1957, earned an average wage but was able to buy a house and become financially secure. He says this is because he lived in an era – the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, where the top rate of tax was significantly higher. Stevenson claims that it’s not a coincidence that, in that period, ordinary people could afford to buy houses.

Stevenson is assuming that, because the top rate of tax was higher in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the rich paid more tax in those decades.

He’s wrong.1

Did the wealthy pay more tax in the 1970s?

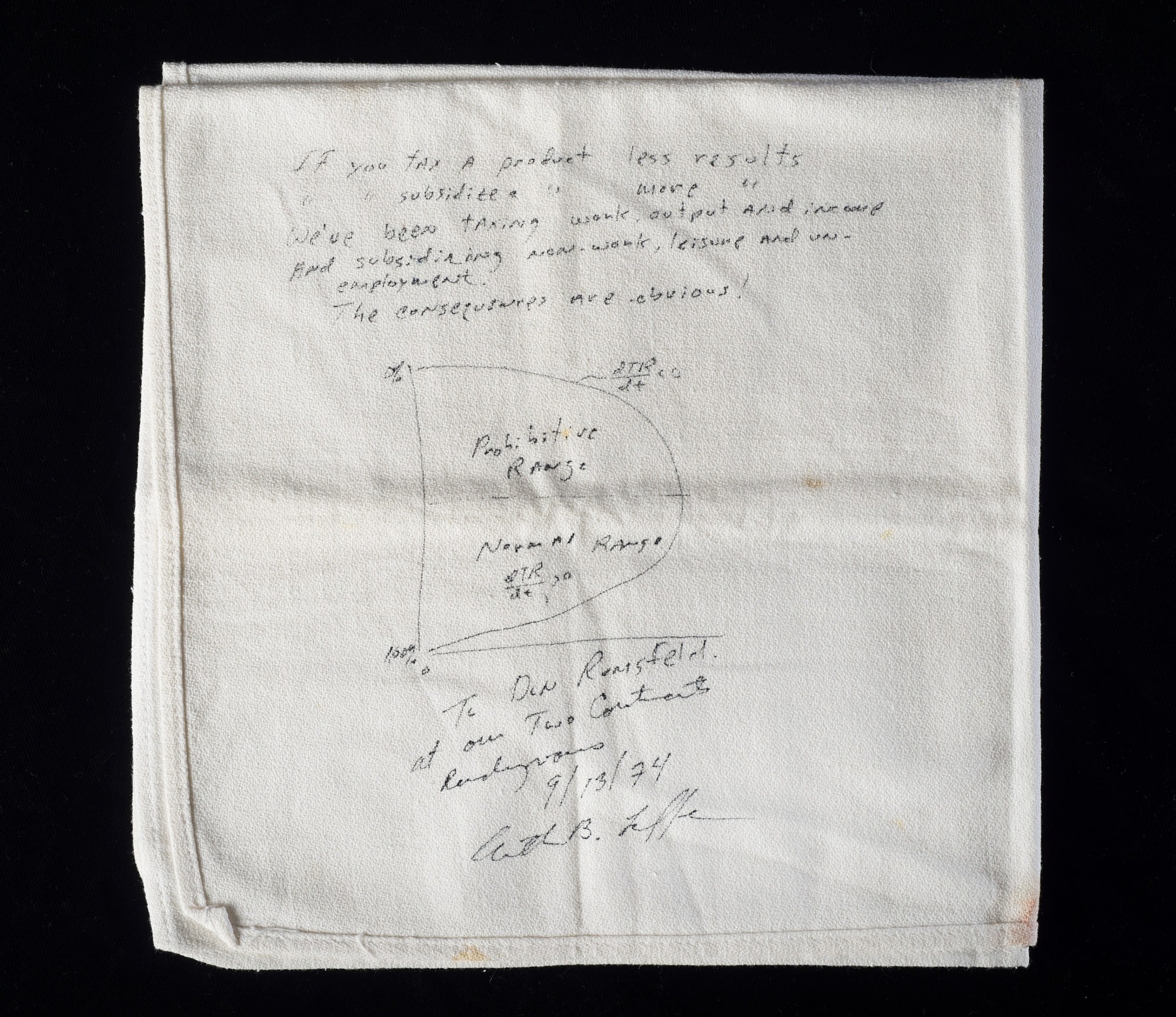

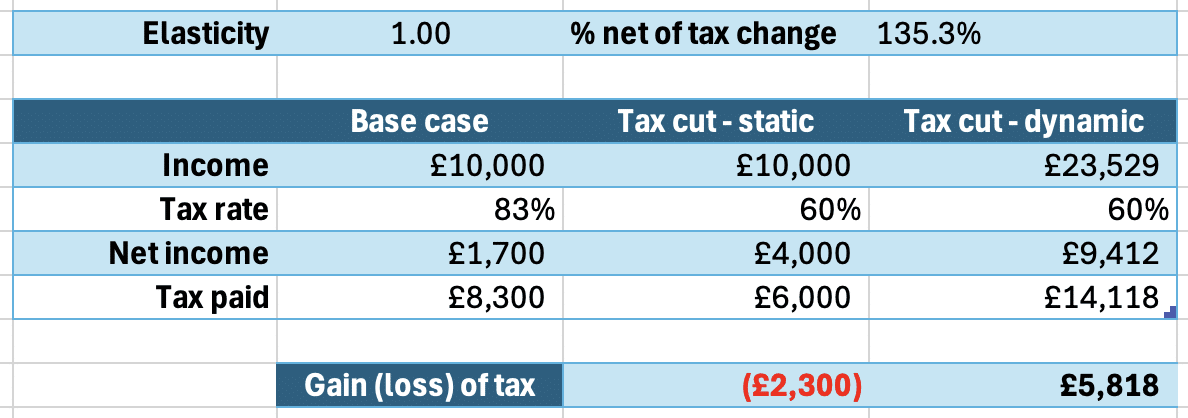

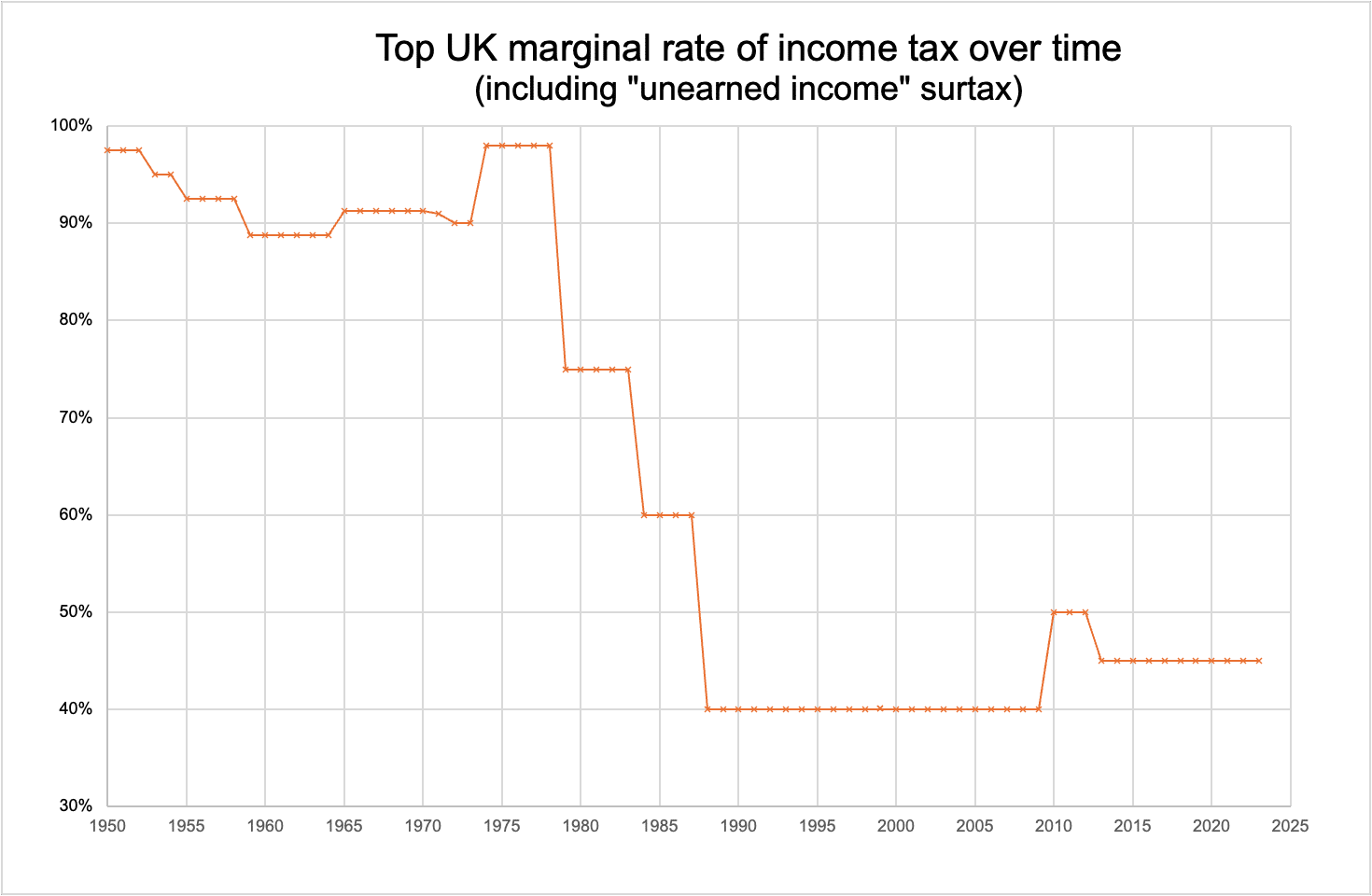

People associate the 1970s with high rates, and they’re correct. UK tax rates reached their peak in 1975, when the top rate of income tax on “earned” income was 83%, and the top rate on “unearned” income (e.g. investment income) was 98%. 2 This was much higher than the rates in other comparable countries.

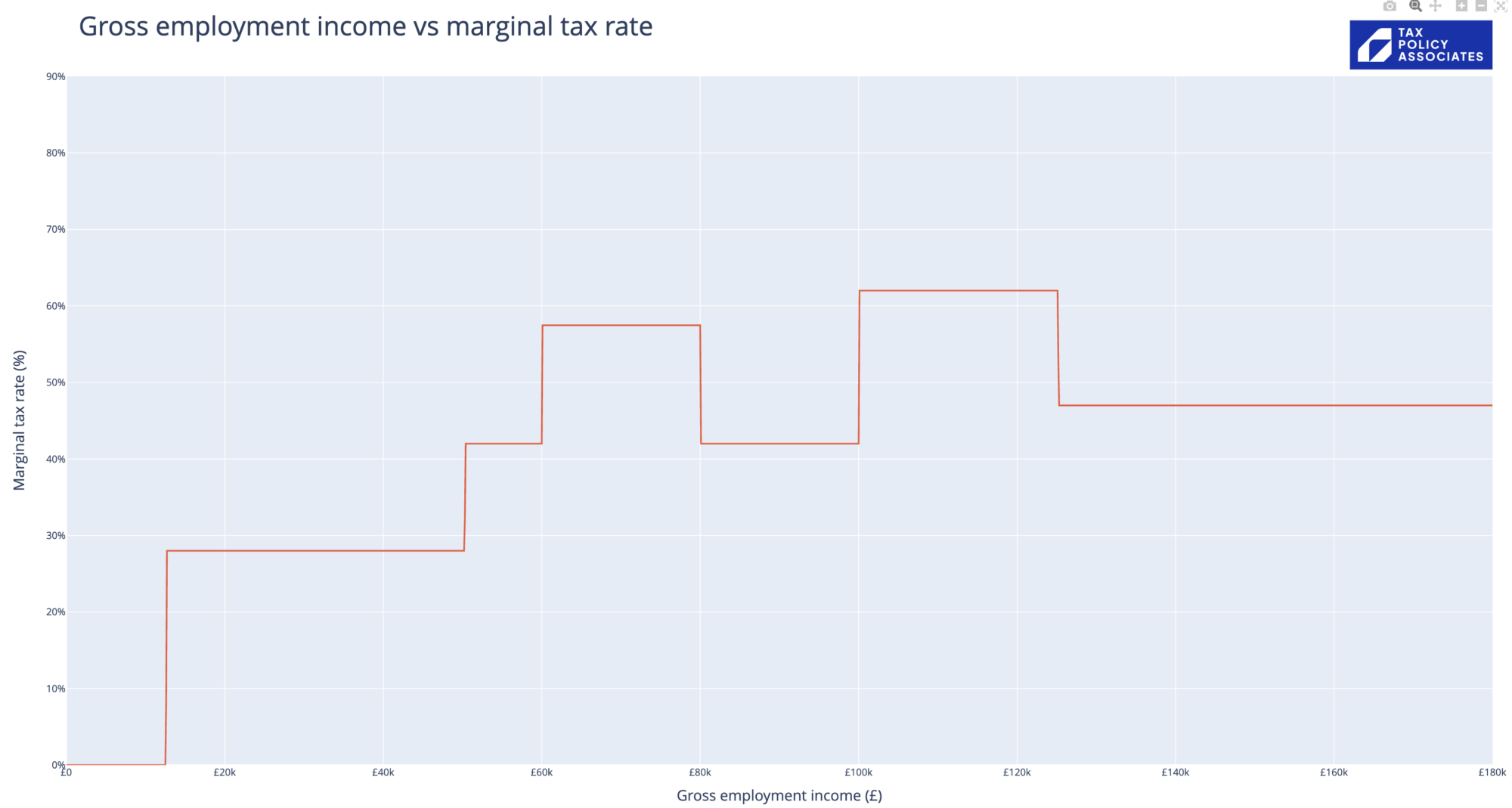

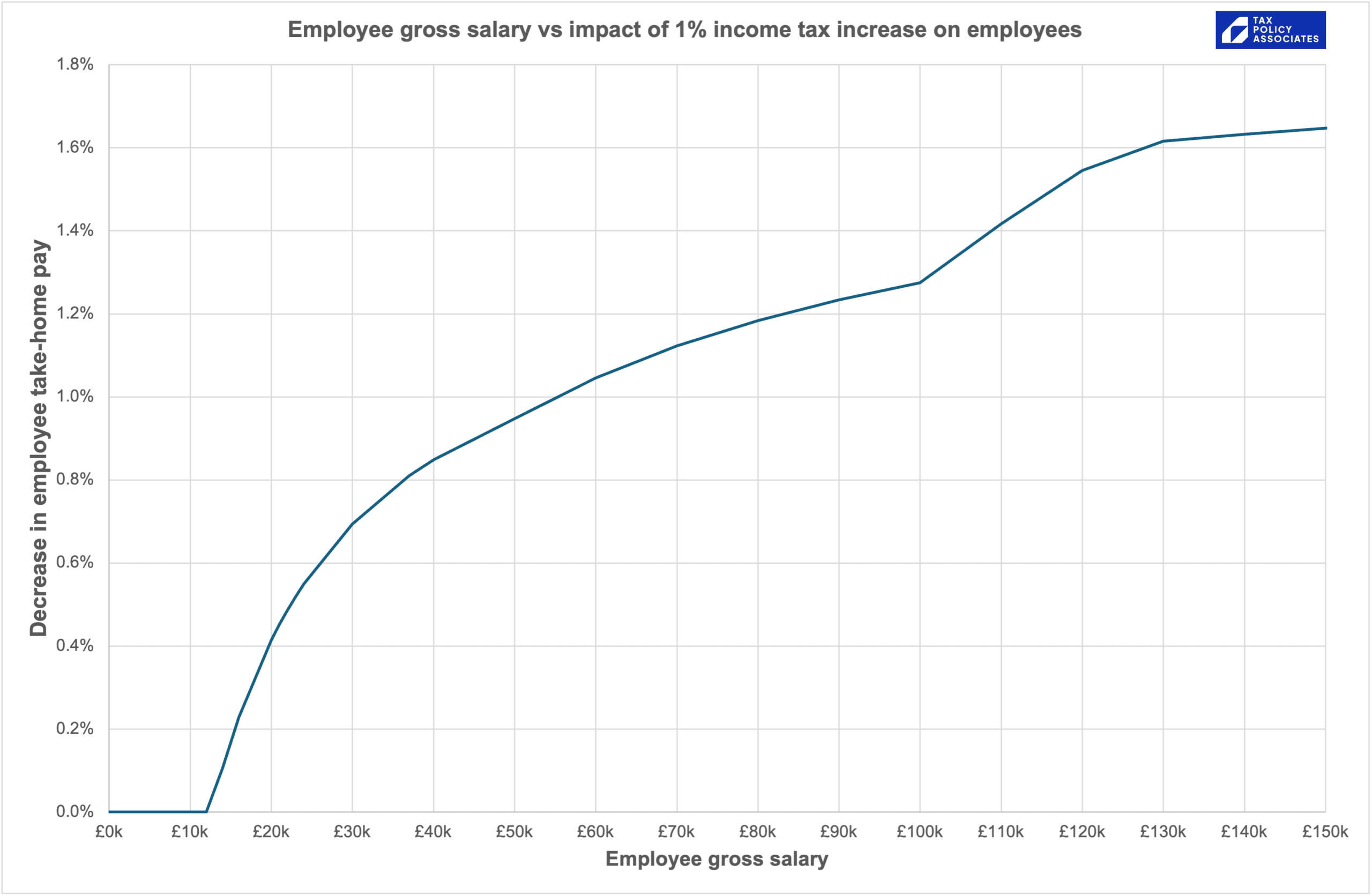

These rates didn’t just apply to oligarchs. The 83% rate applied to incomes over £24,000; in today’s money, around £120,000. So we’re talking about incomes that were high, but not exceptionally high. To put it in context, £24,000 was about five times average 1979 earnings, and twice the salary of a headmaster.3

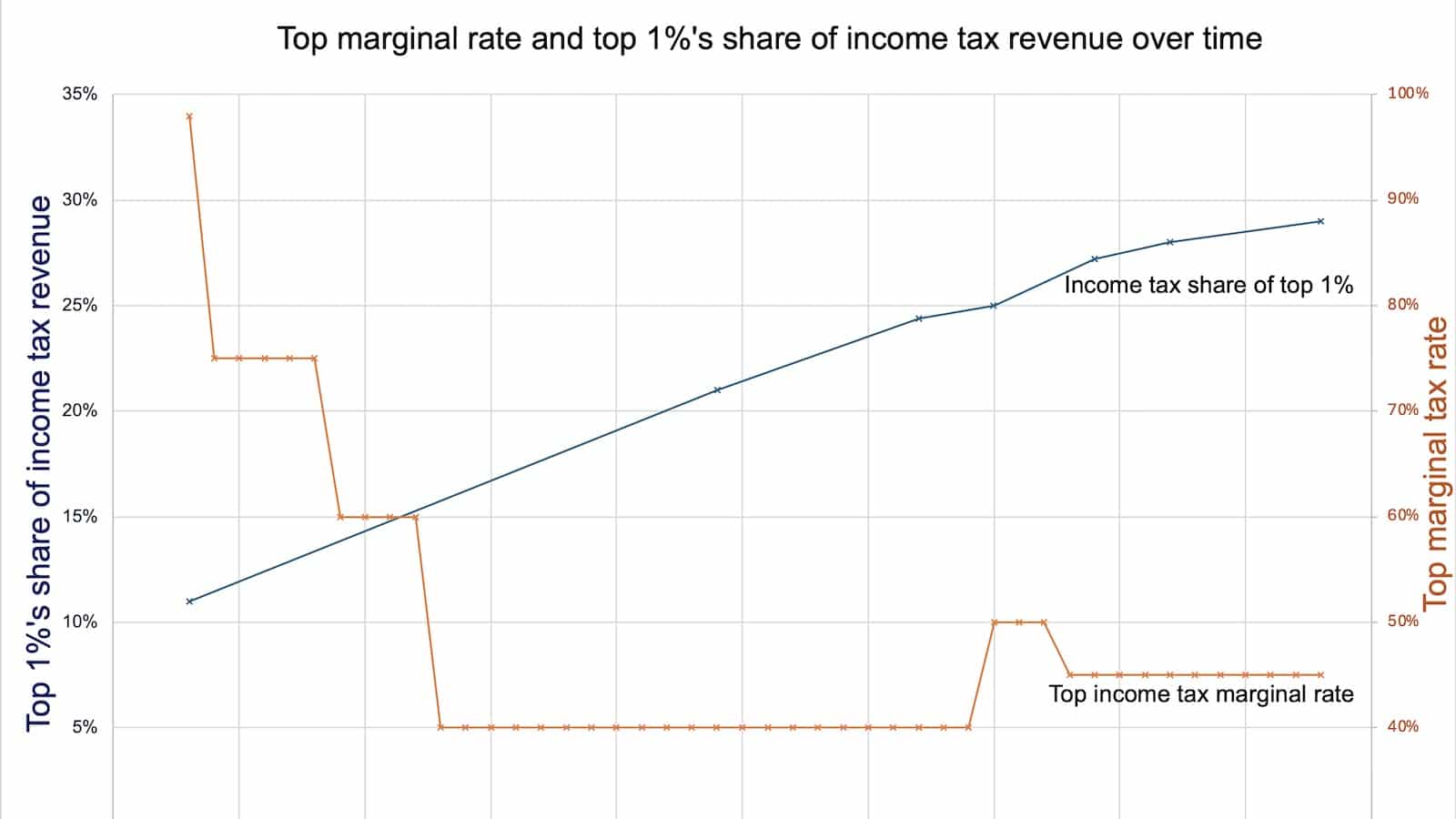

After the 1970s, the rate fell precipitously:45

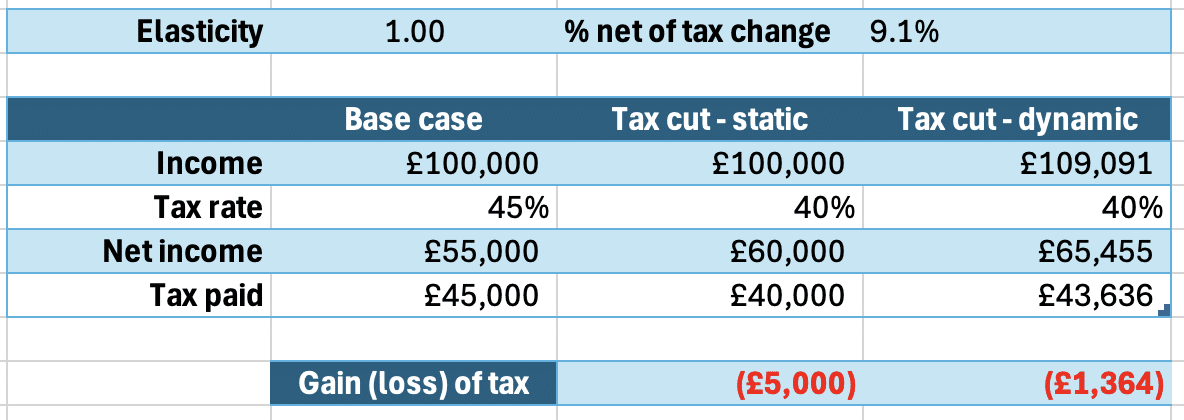

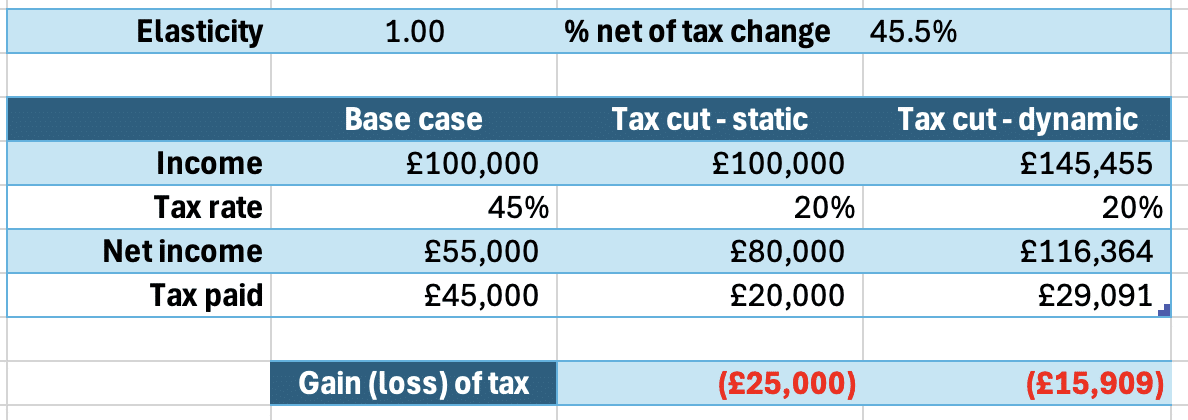

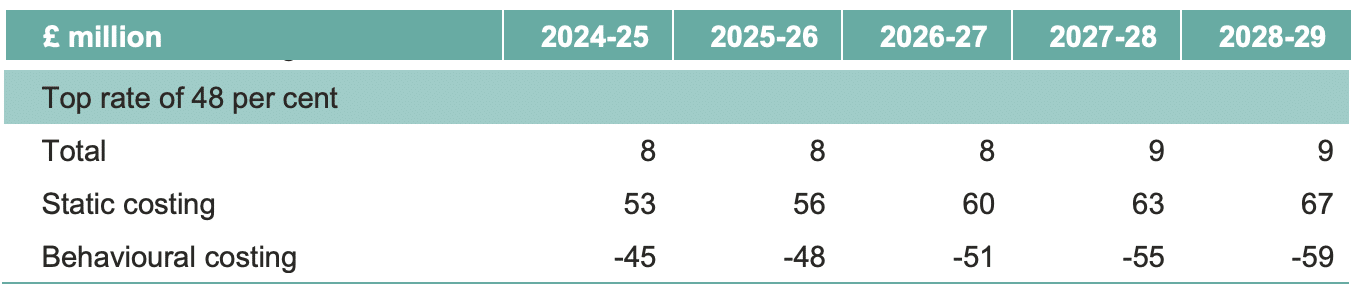

Today, the top rate of income tax on most income is 45%6 and 48% in Scotland.7

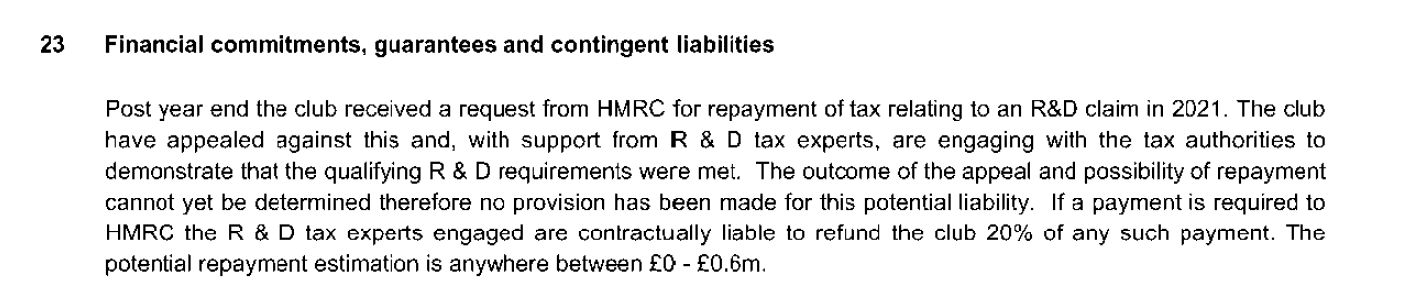

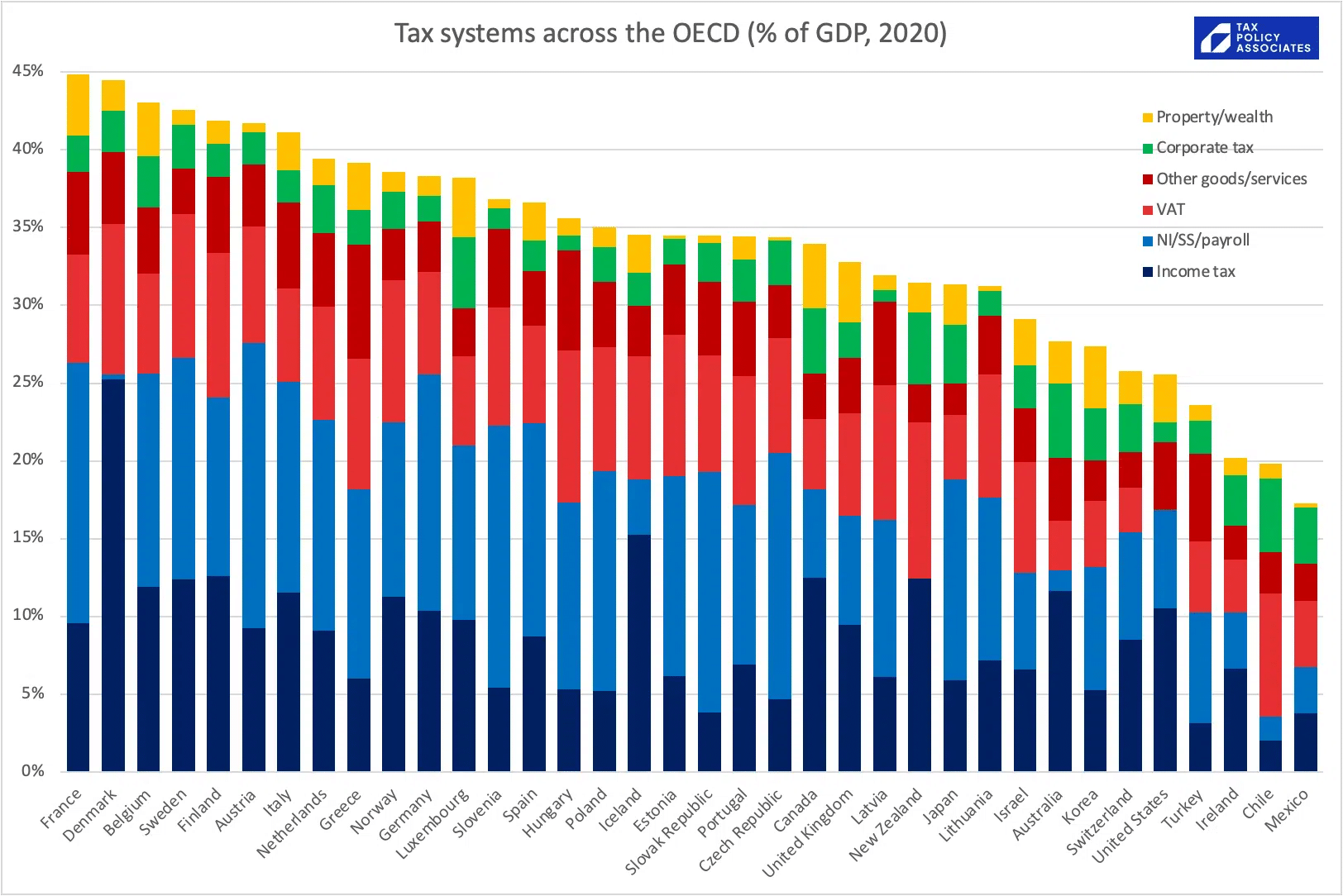

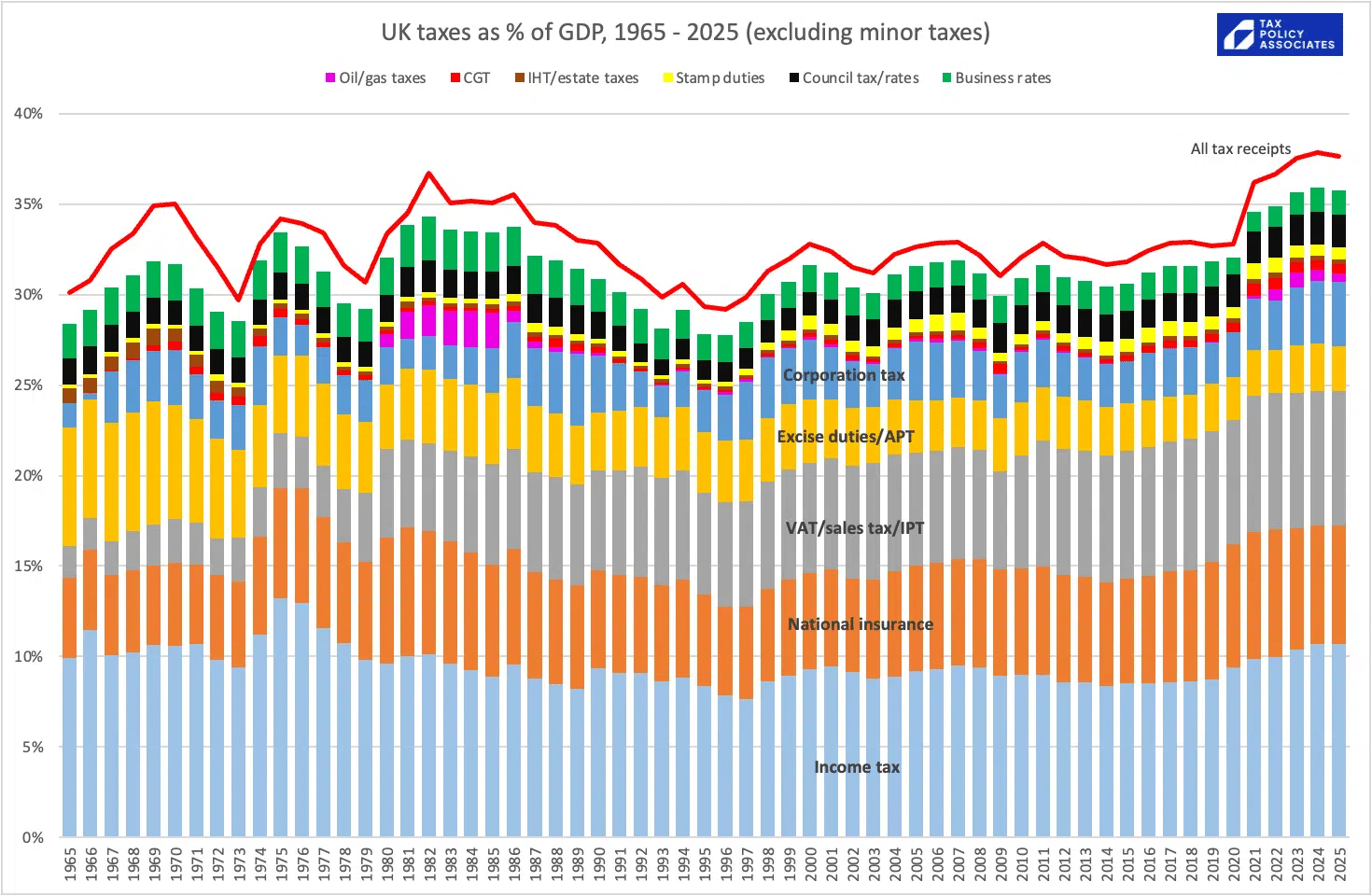

So all of this suggests there must have been a lot more income tax paid in the 1970s than today. But there wasn’t.8 Income tax raised about the same in the 1970s (as a percentage of GDP) as it does today:9

Perhaps this is because most people paid less income tax in the 1970s than today, but high earners paid a lot more?

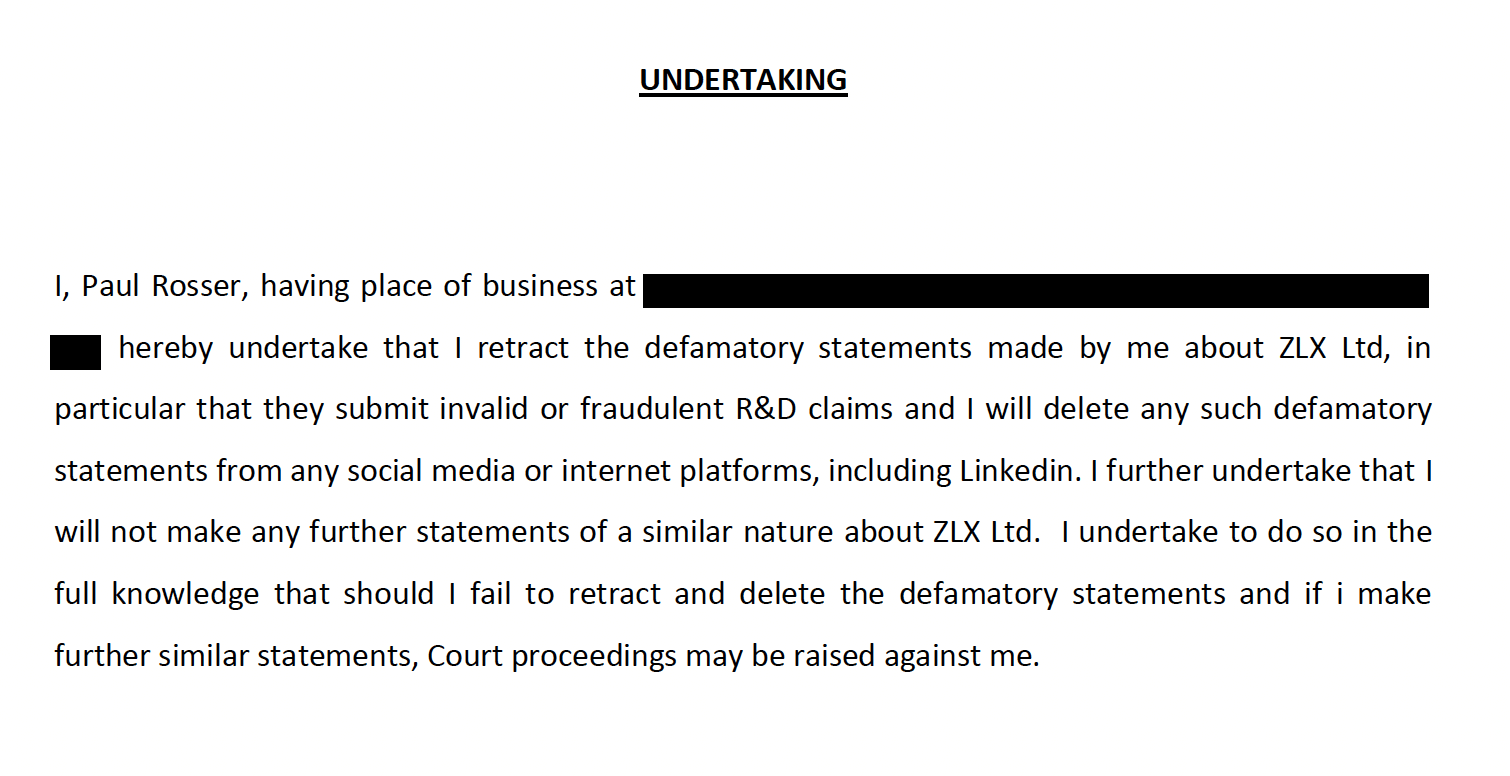

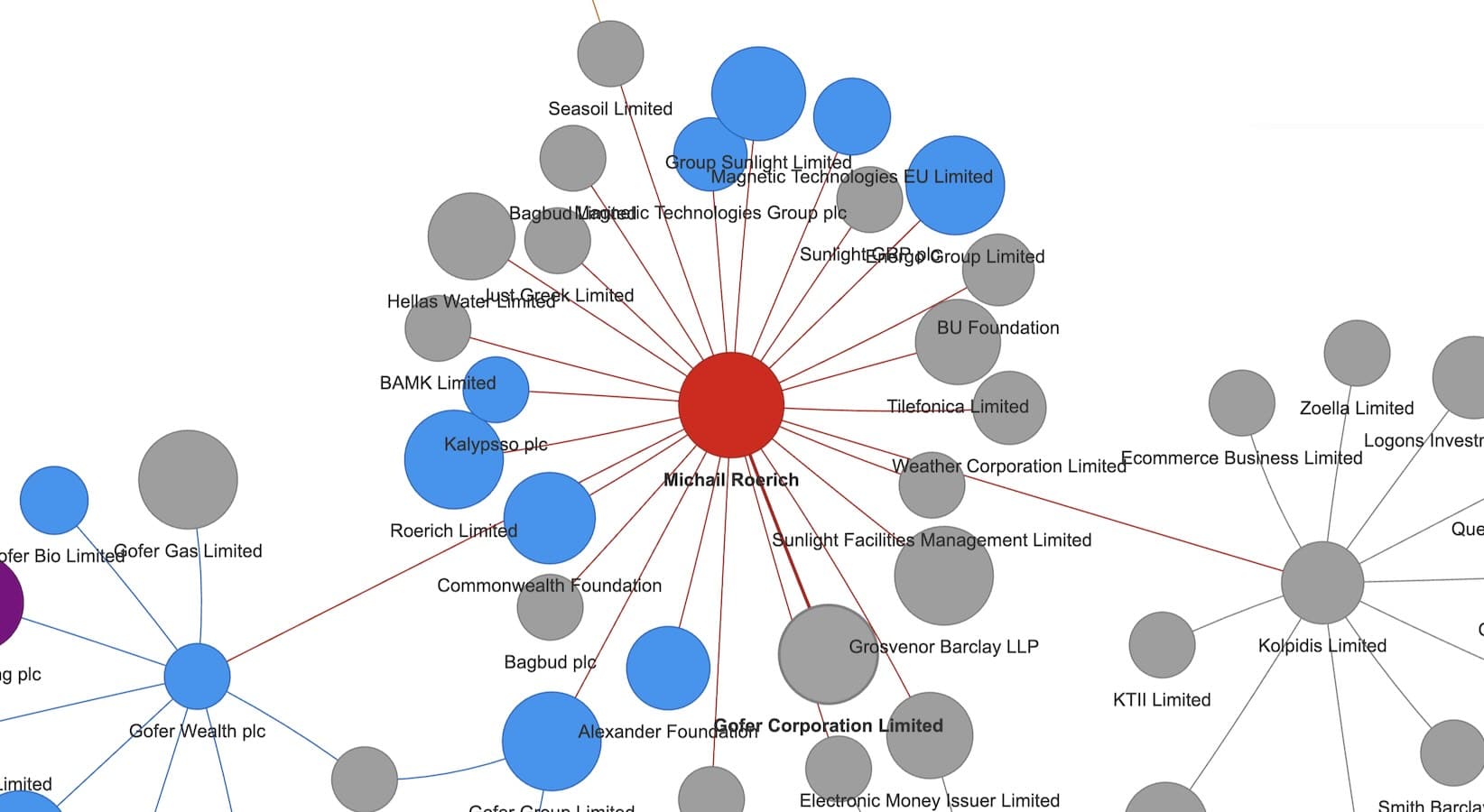

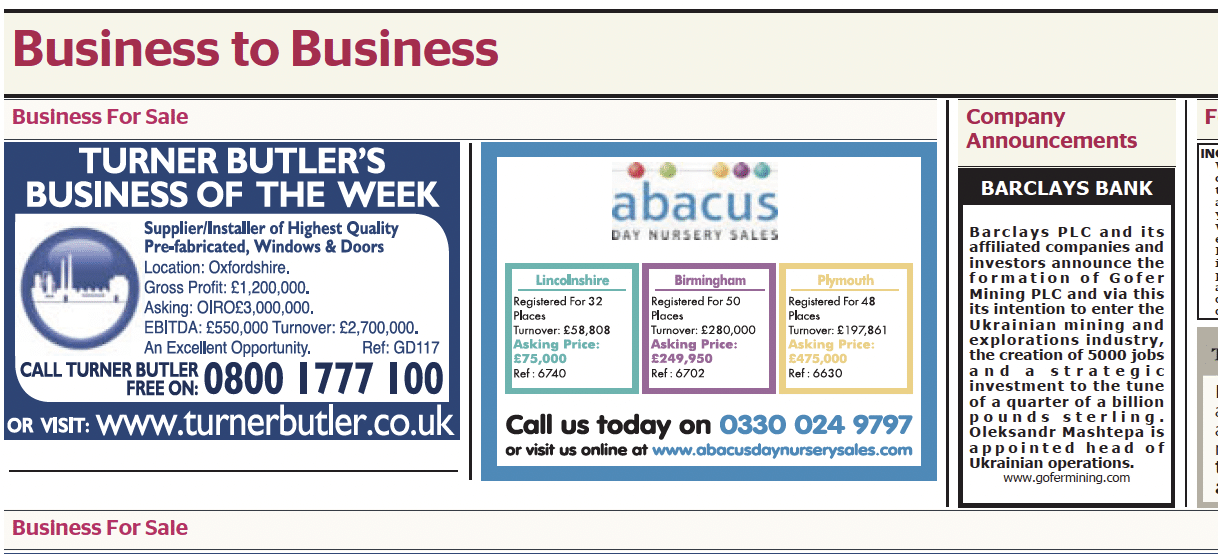

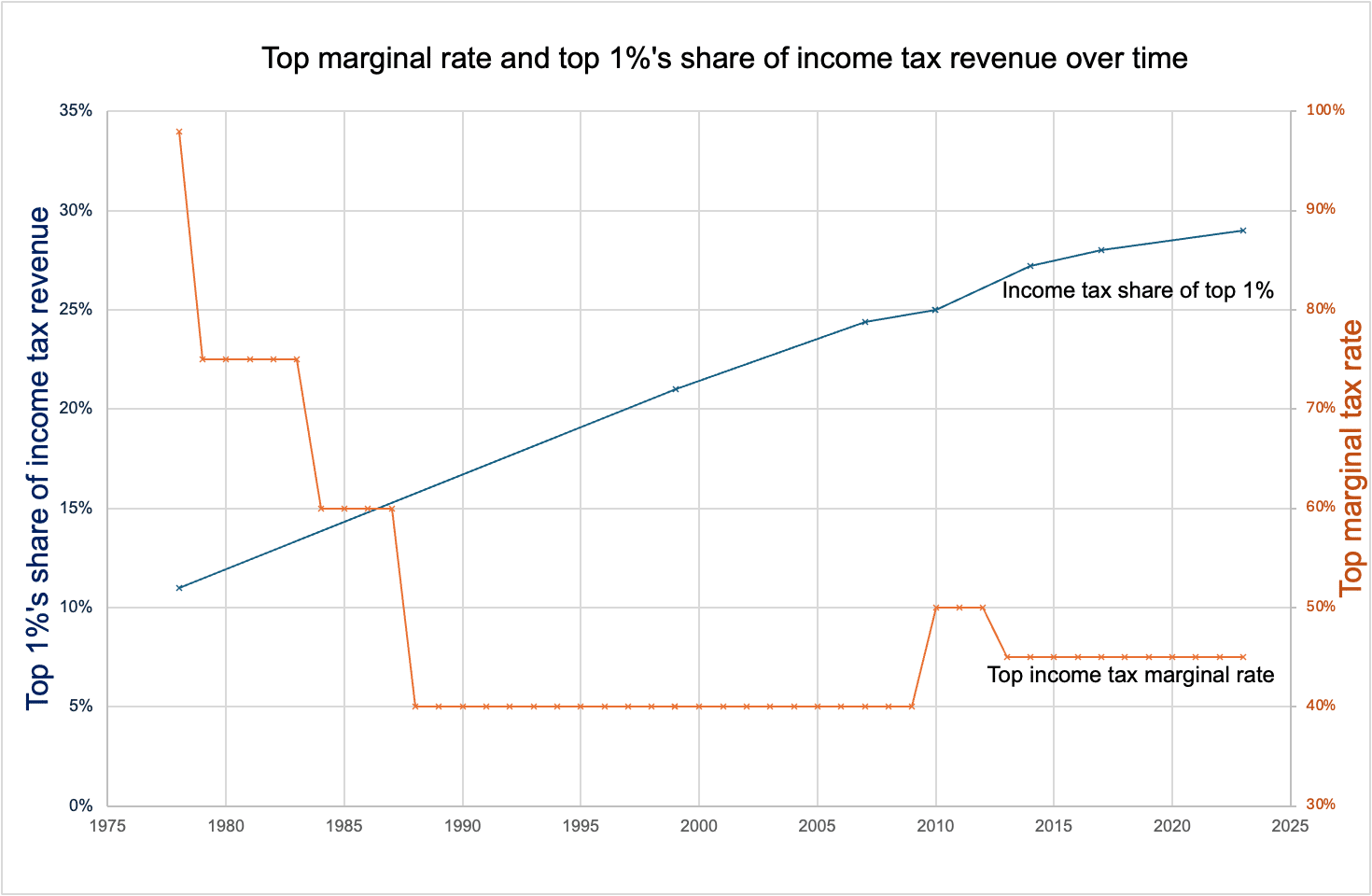

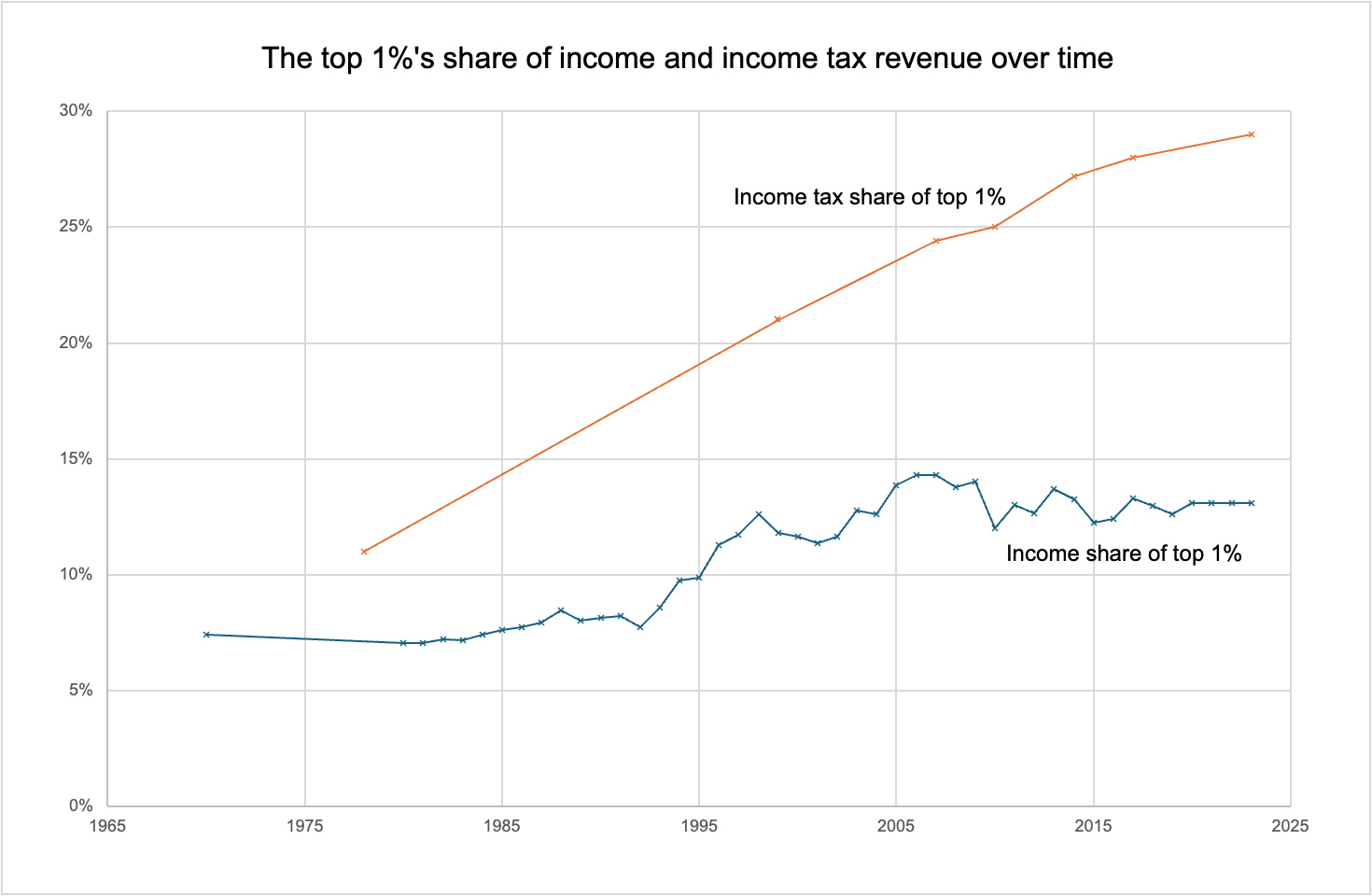

The opposite is the case. In 1978/79, top 1% paid 11% of all income tax. In 2024/25, the top 1% will pay about 29% of all income tax. The trend is extraordinary:10

How can that be, when the rate of tax paid by the top 1% is less than half of what it was?

There are three explanations.

The first is simply that the top 1% earn more (as a percentage of national income) than in the 1970s.

The World Inequality Database contains estimates of the top 1% income share over time, and is compiled by an international consortium of academics. Here’s what happens if we add this data to the previous chart showing the top 1%’s share of income tax revenue:11

It’s reasonably clear from this that a rise in income share is an incomplete explanation.121314 Over a period when, to stress the point, the rate of tax paid by highest earners has fallen by half.15

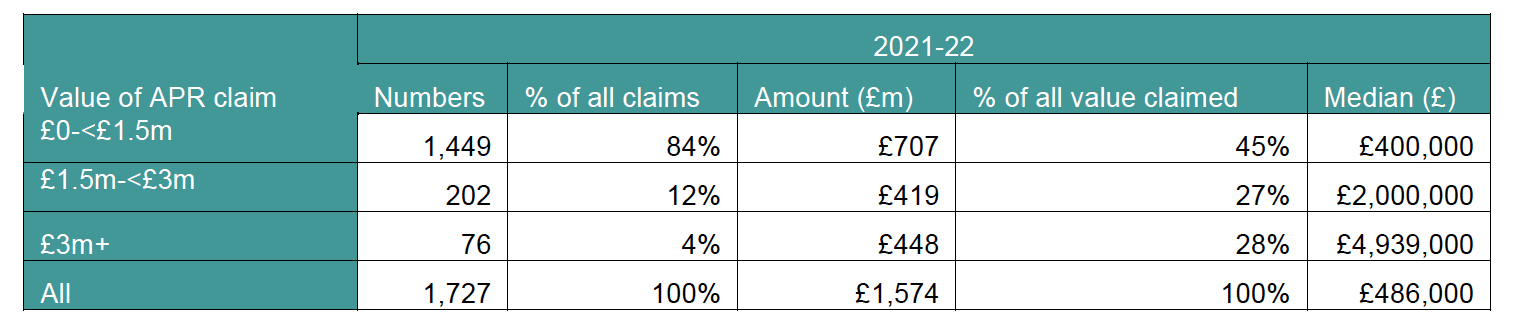

The second is that about a third of the increase in the tax paid by the top 1% is recent, and was caused by a series of tax changes since the financial crisis that increased the tax burden on the 1%. Or, to be more precise, those in the lower levels of the 1% (i.e. incomes less than around £200,000). These include the introduction and freezing of the additional rate band and the clawback of the personal allowance.

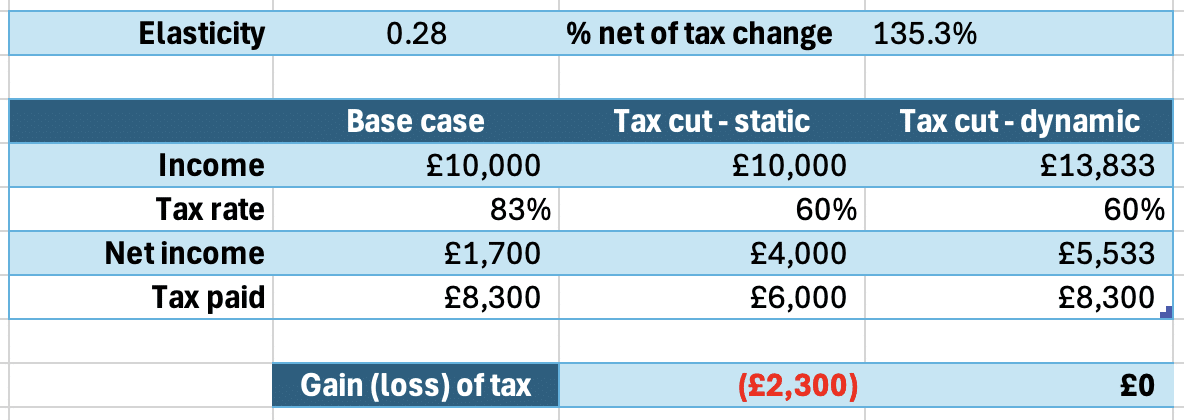

The third, and least discussed, is that the high rates of the 1970s are illusory – they don’t reflect the tax that the 1% were actually paying. The reasons why are interesting.

The illusion of high rates

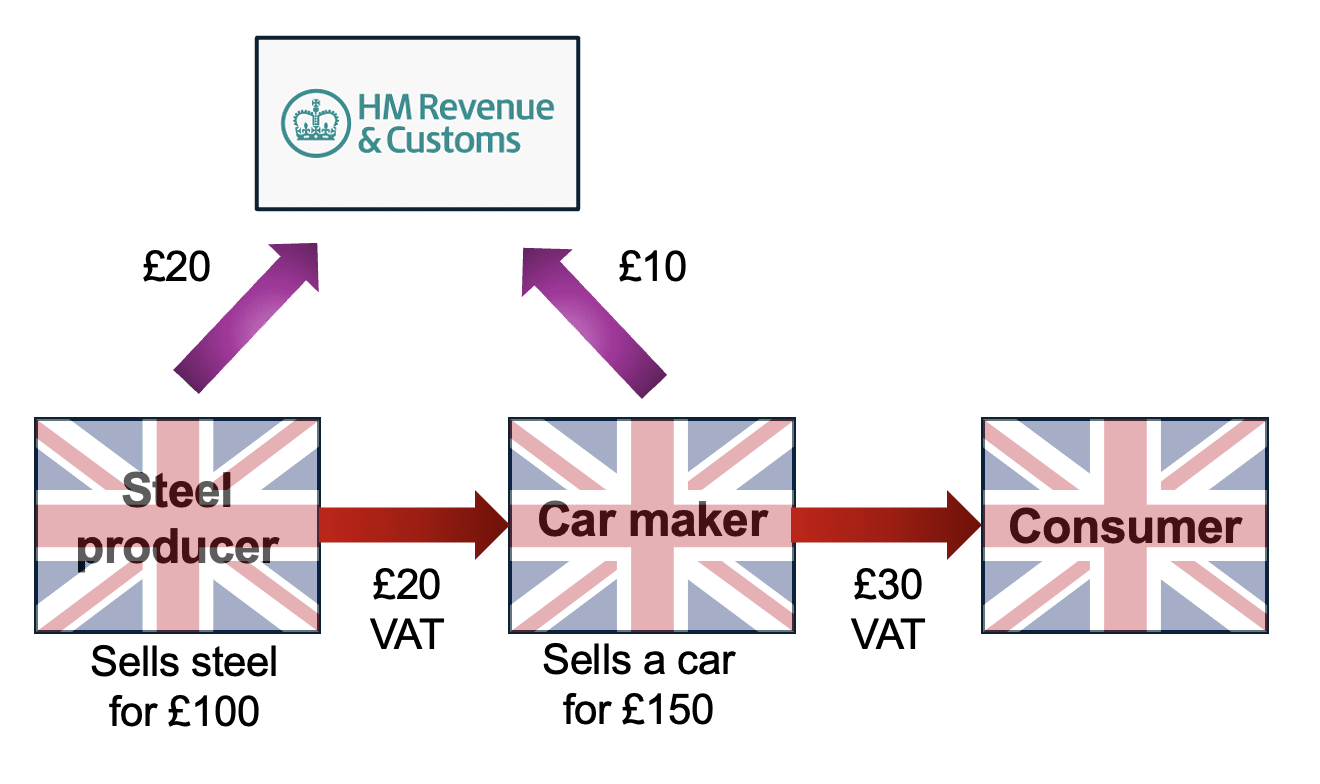

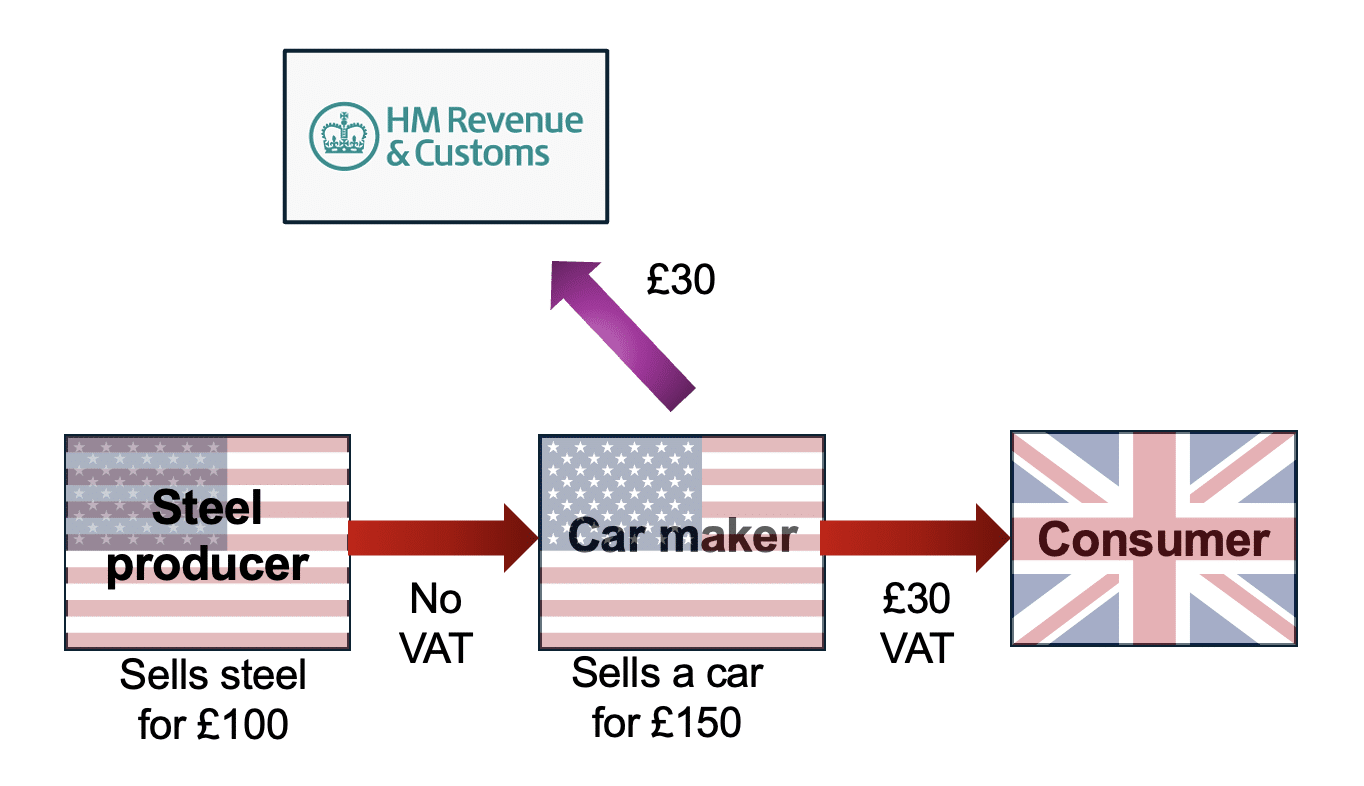

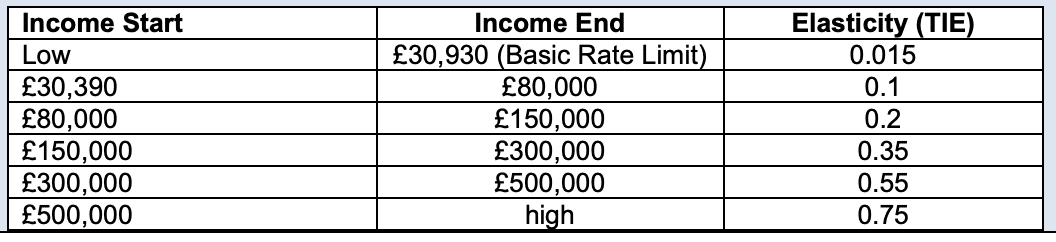

There is a difference between the “statutory” (or “headline”) rate of a tax and its “effective” rate.

The statutory rate is what the legislation says – so, today, that’s a top income tax rate of 45%16

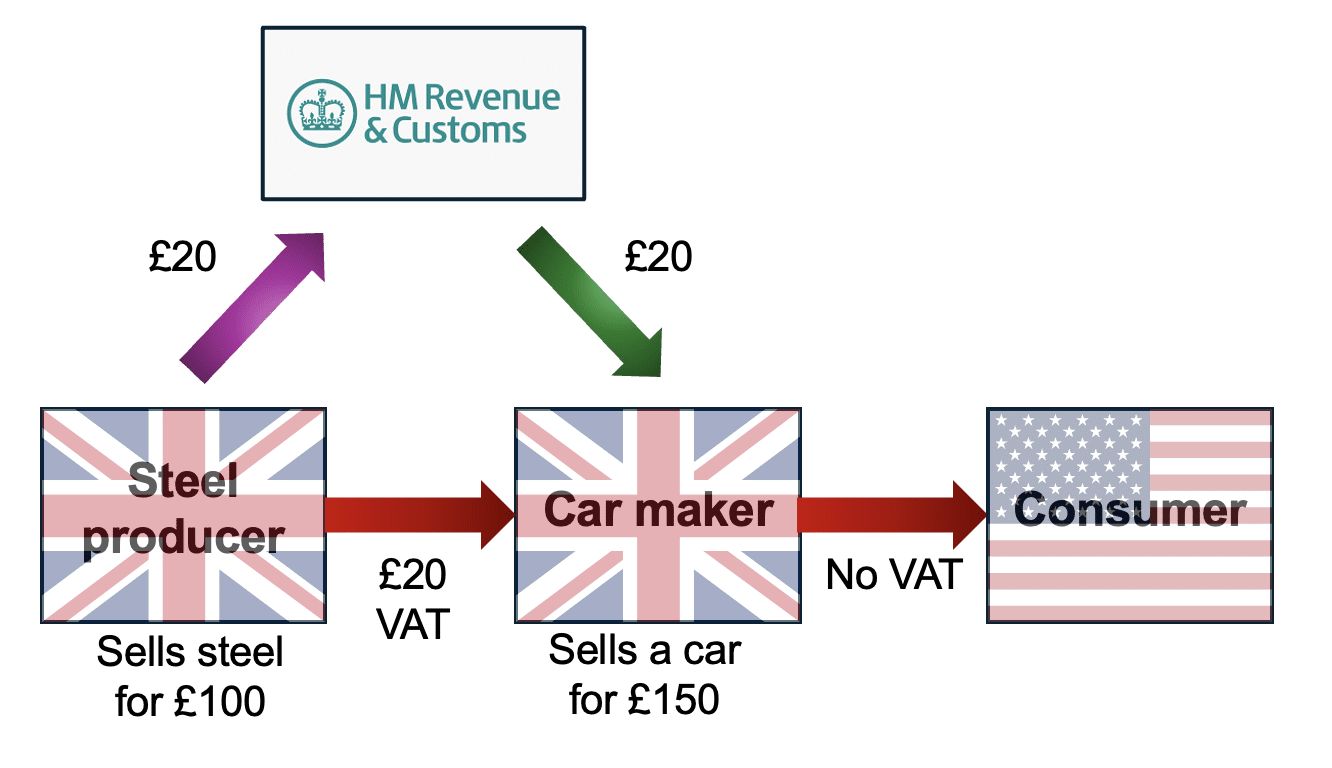

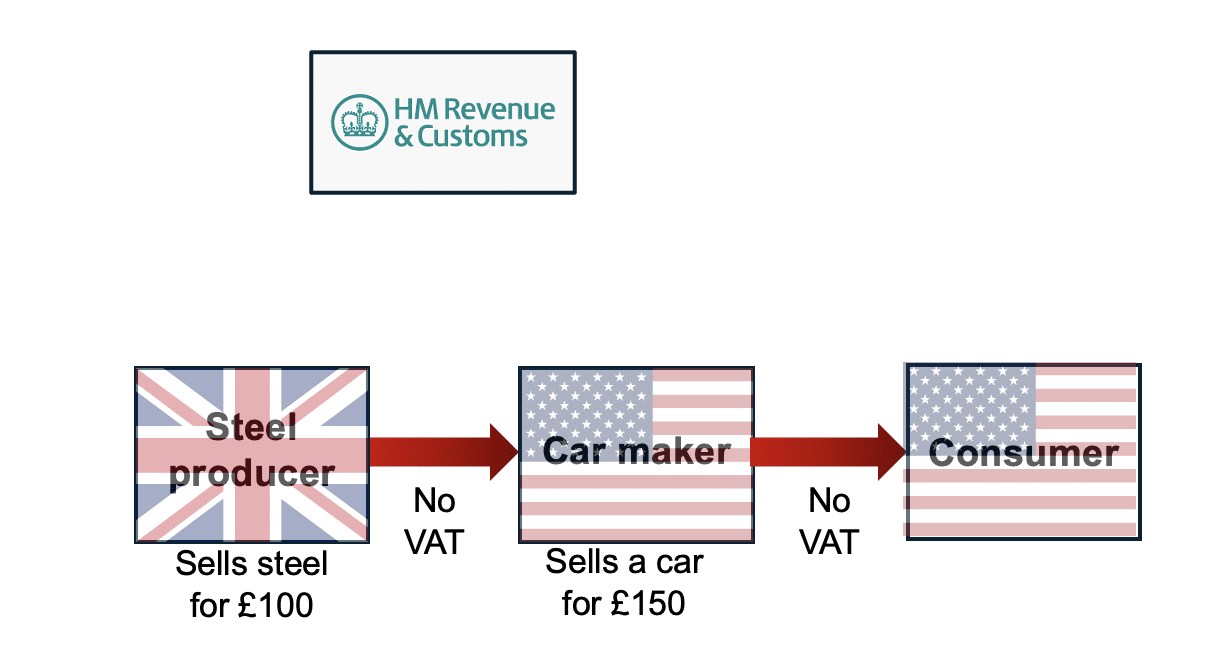

But all taxes result from a calculation involving two numbers – the rate is multiplied by another number – the “base“. For income tax the base is the taxable income. And the base has changed dramatically since the 1970s. It’s become much wider, which means that 45% of the tax base today is a much larger number than 98% of the 1970s tax base.17

The short version is that, in the 1970s, tax law was much simpler – there was less tax legislation, and fewer statutory anti-avoidance rules. The courts also had a generally forgiving attitude to tax avoidance. This was well-known at the time – as early as the 1950s, commentators were describing UK tax policy as “the path charging more and more on less and less”.18

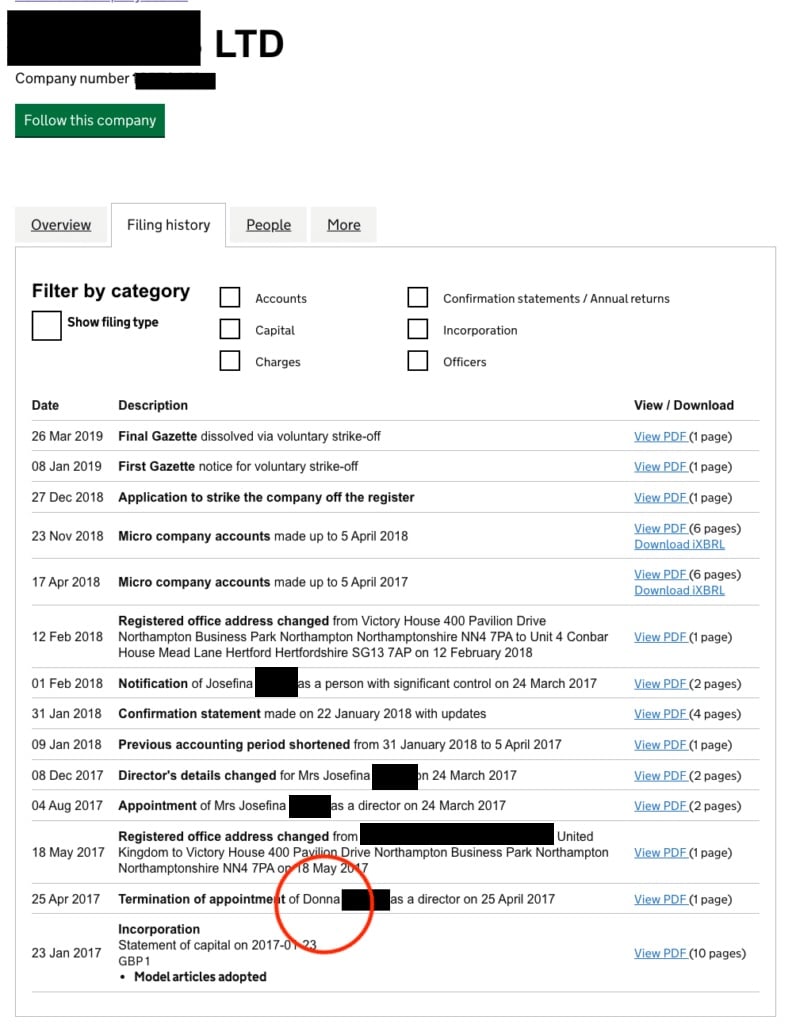

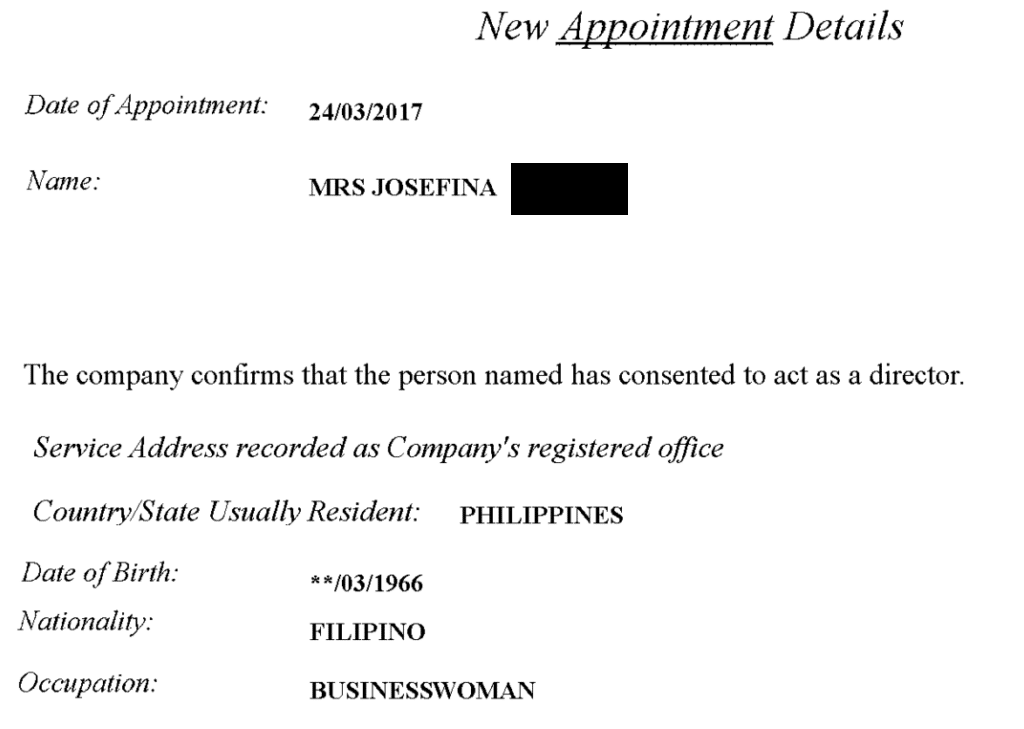

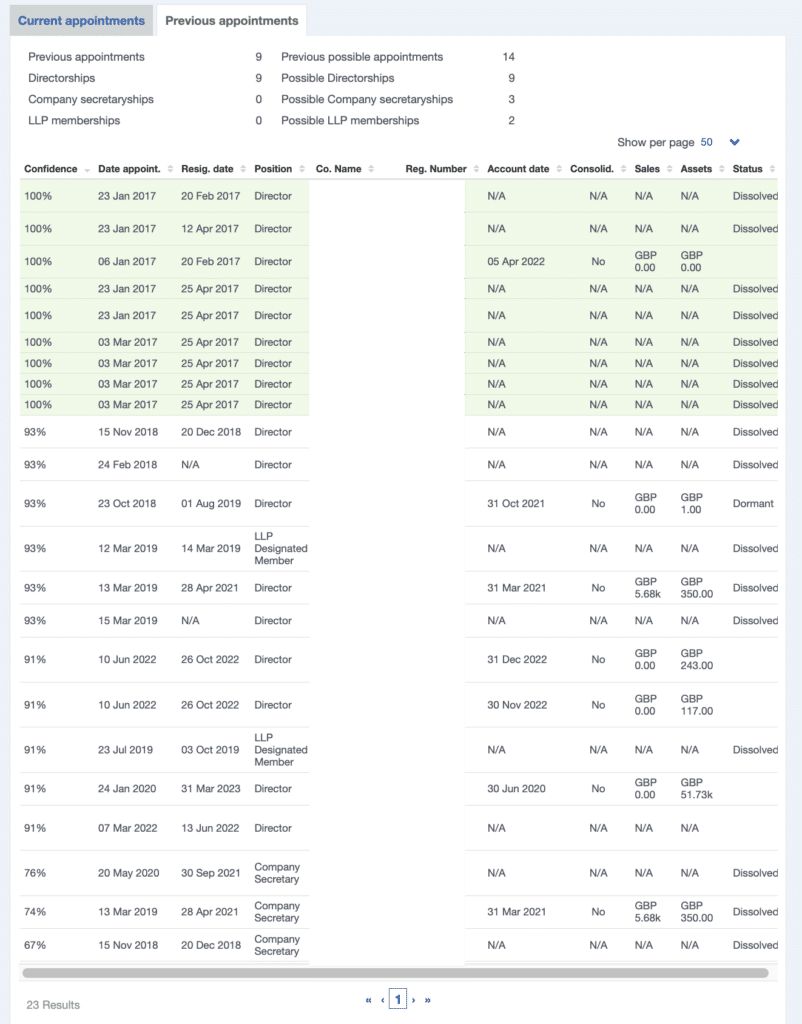

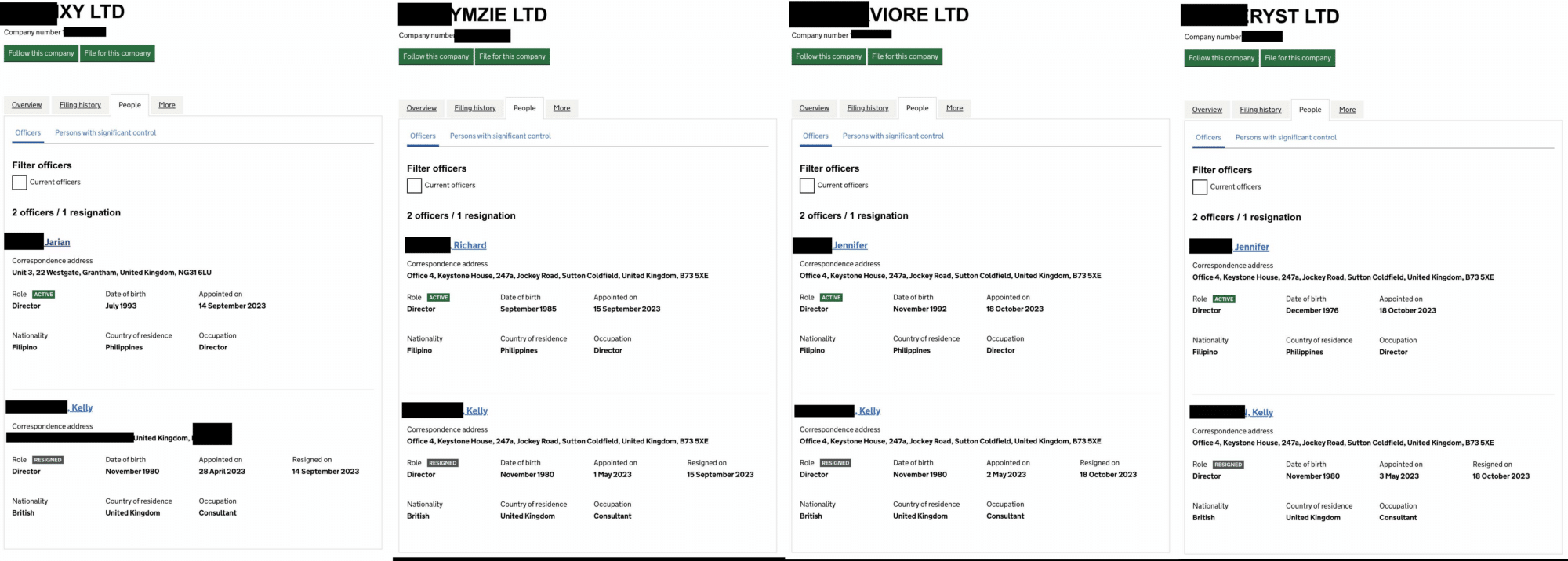

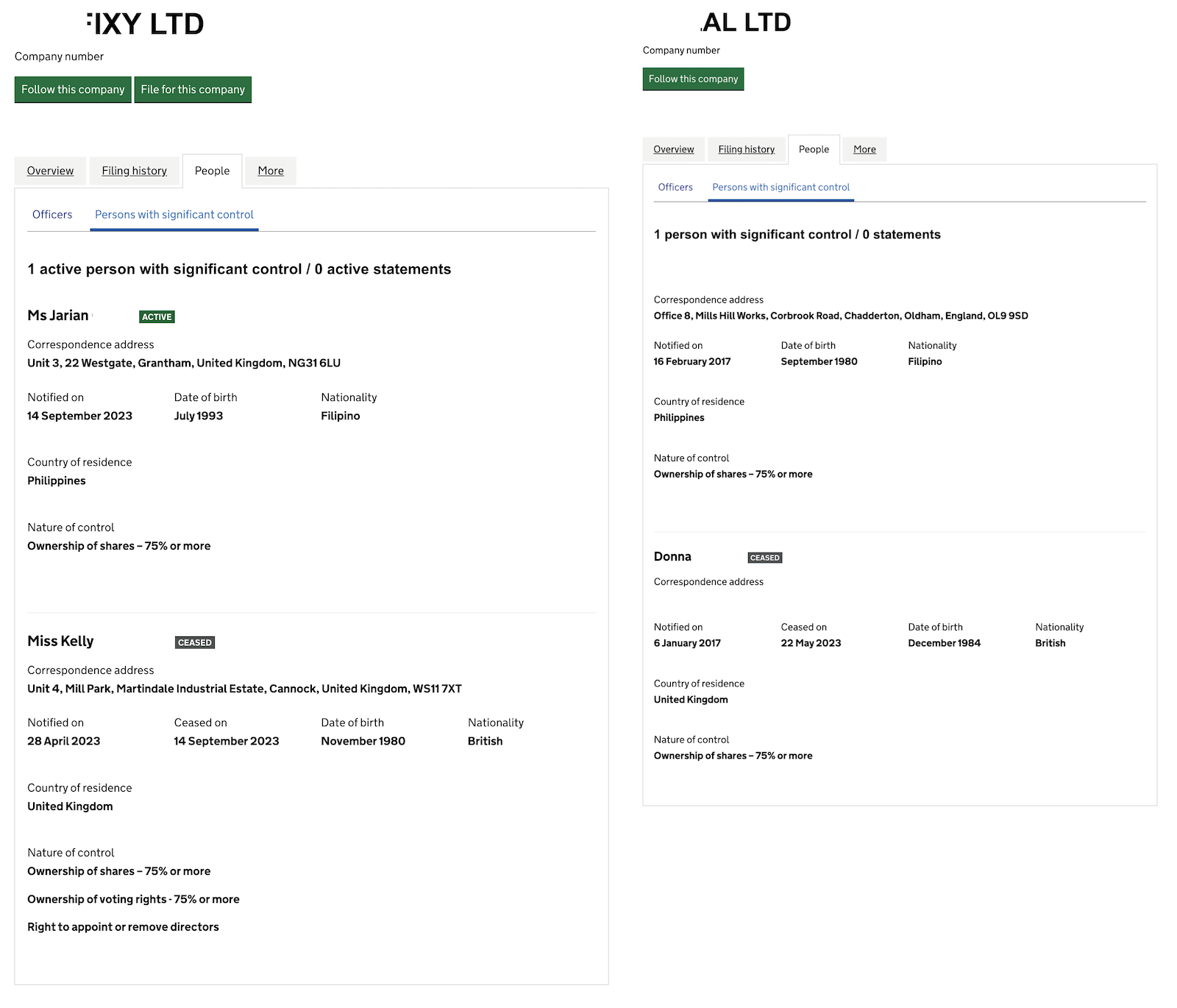

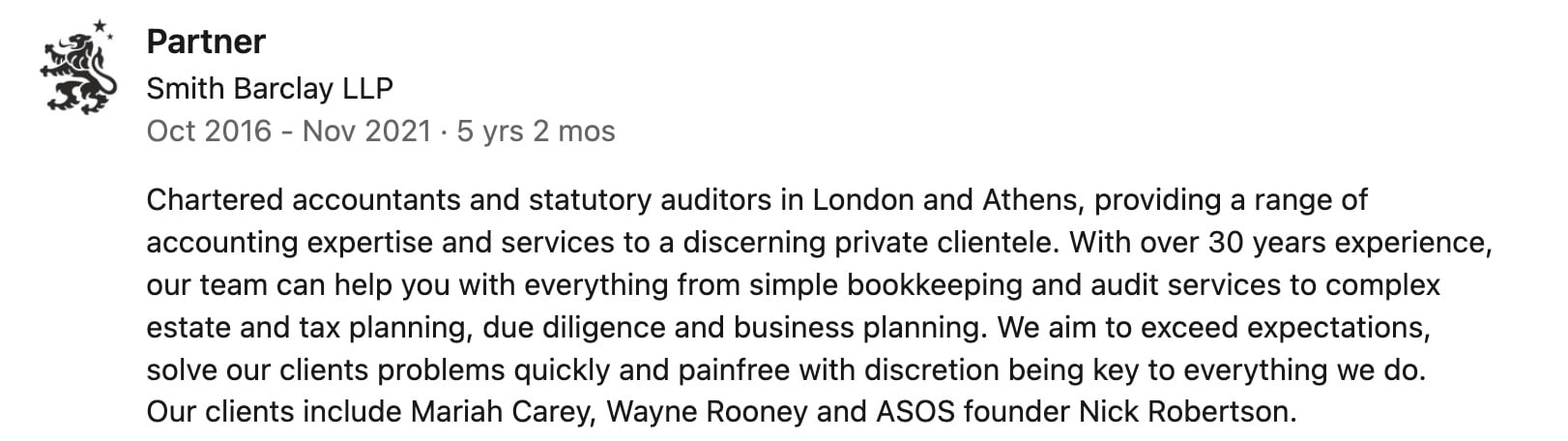

To discover the longer version, I’ve spoken to a variety of retired HMRC officials, tax advisers and businesspeople who either used or tried to stop the tax tricks of the 1970s. Here’s what they say:

- A pop star suddenly making huge sums isn’t in a position to control their income. A senior executive, or the owner of a private company, is. So, if a bonus would be taxed at 83%, or a dividend at 99%, the first step is: don’t take a bonus or dividend. Do something else. There were many something elses.

- Simplest and most effective: benefits in kind were undertaxed or completely untaxed. Today, any benefit an employee receives from their employer is taxable as a “benefit in kind”. Until 1970, benefits were mostly untaxed. After the Income and Corporation Taxes Act 1970, benefits were taxable – but only where they could be directly converted into cash. Later they became taxable on a more general basis, but assessed at the cost to the employer, not the value to the employee – a rule which was easily abused.19 So high earning salaried employees (say executives) would avoid tax by taking much of their remuneration in the form of extensive “perks” or “fringe benefits” from their employer instead of cash salaries. Cars, housing, travel, holidays, club memberships, dining out, the “luncheon voucher“… all enabled a very high standard of living to be obtained tax-free.20 And all of this was tax-deductible for the employer. These perks assumed a much greater importance in the 1970s than before or since, and across all income levels, but became particularly significant for high earners. Tax was not the only motivation: perks were a way of side-stepping statutory pay controls. The consequence was that perks replaced a significant proportion of high earners’ salaries and bonuses (troubling some researchers at the time).21

- Until 1976, companies could lend large sums to their executives and charge zero interest. Rules were enacted in 1976 charging the benefit of no/low interest rate loans to income tax, but they were widely avoided.

- Perks and interest-free loans enabled tax-free remuneration of executives during the time they were employed. Once they retired, generous pension rules would enable very large lump sums to be paid to executives tax-free.22

- All interest was fully tax-deductible until 1974. The rules then changed so that only interest on business loans and home mortgage loans was deductible, with mortgage interest capped at £25,000 (£125,000 in today’s money). But that was still pretty generous. And for someone paying tax at a marginal rate of 98%, their interest would be almost entirely paid for by reduced tax liability. A common response to receiving a pay rise (by middle class professionals, never mind the 1%) was to take out a larger mortgage. What’s now called the “buy, borrow, die” strategy was highly effective – at the time it was often called “living in debt”.23

- People born abroad but living in the UK (“non-doms”) could live in the UK for decades but pay no tax on their foreign earnings; until 1974 there were loopholes which meant they could easily pay no tax on their UK earnings either.24 And, until as late as 2017, people who had lived in the UK all their life, not even born abroad, could sometimes claim to be non-doms.

- Before the introduction of Capital Transfer Tax in 1974/75, lifetime gifts into trusts weren’t taxed. Distributions to trust beneficiaries in principle were taxable, but easy to avoid, and the Inland Revenue had difficulty tracking such distributions.

- Someone about to make a large capital gain (say by selling their company) could leave the UK and become a tax exile, take the capital gain tax free, and then return to the UK the very next tax year (or, with the right timing, nine months later). The same trick would work for someone expecting a large stream of income, such as royalties – there’s a reason why so many musicians became “tax exiles” in the 1970s. This continued to be a highly effective strategy until the “temporary non-resident” rules were introduced in 199825 – tax exiles today need to be willing to leave the UK for five years, which many are not.

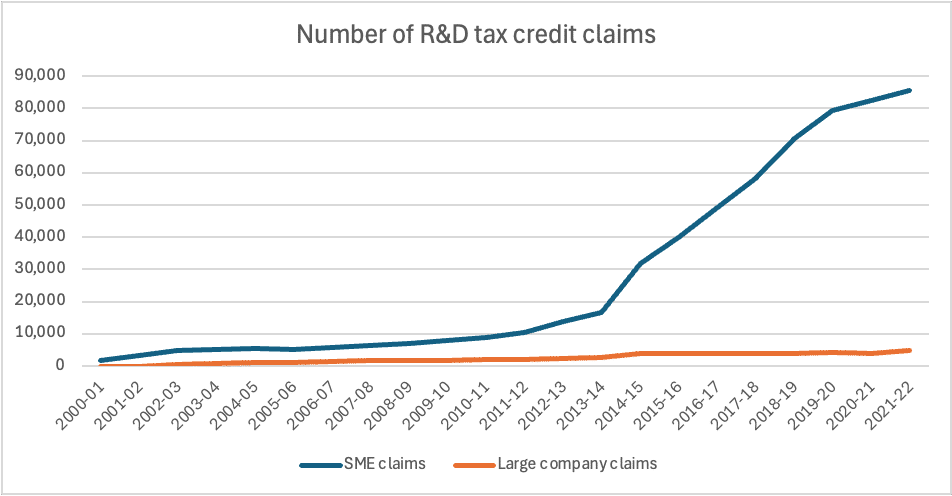

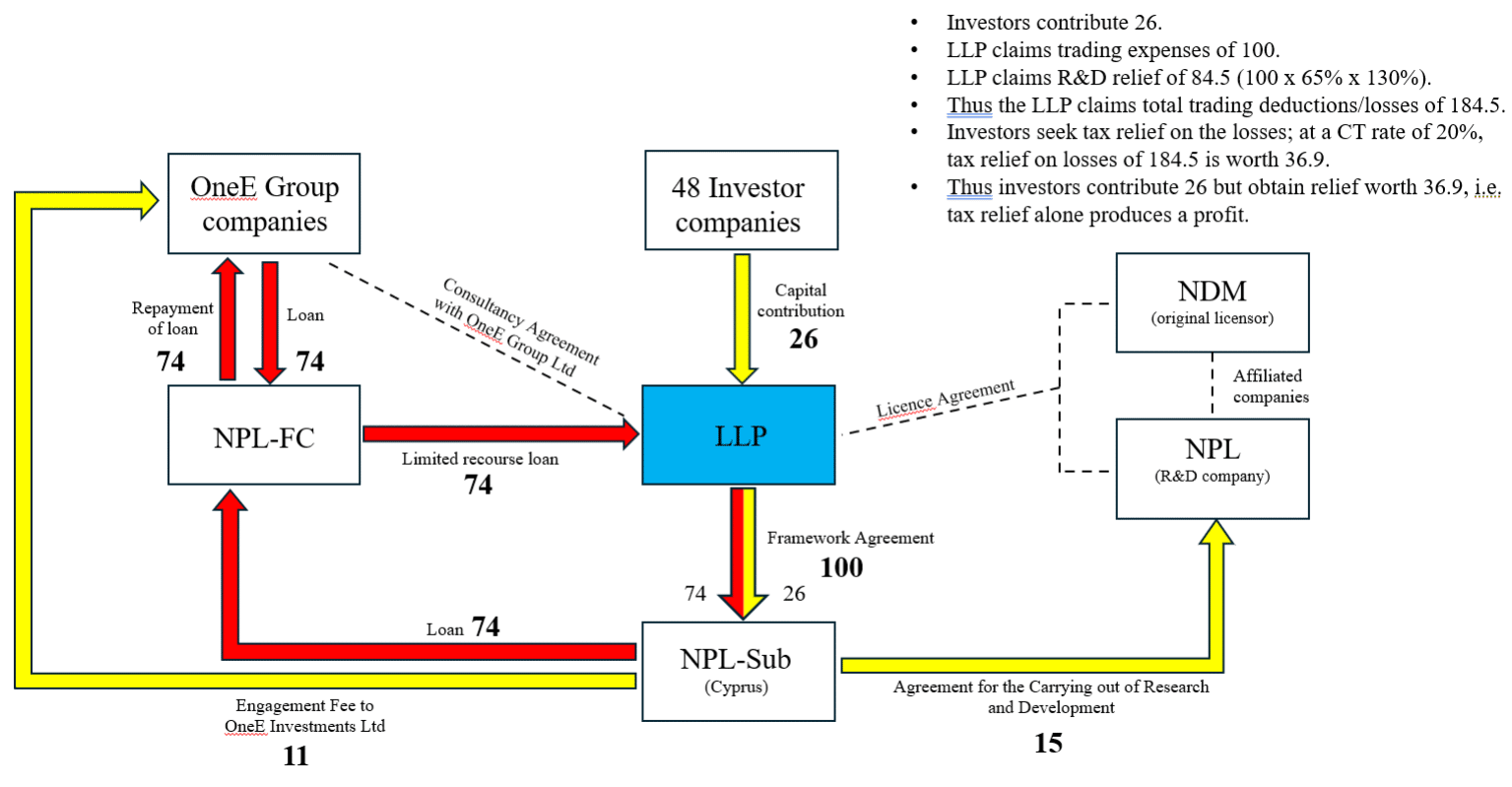

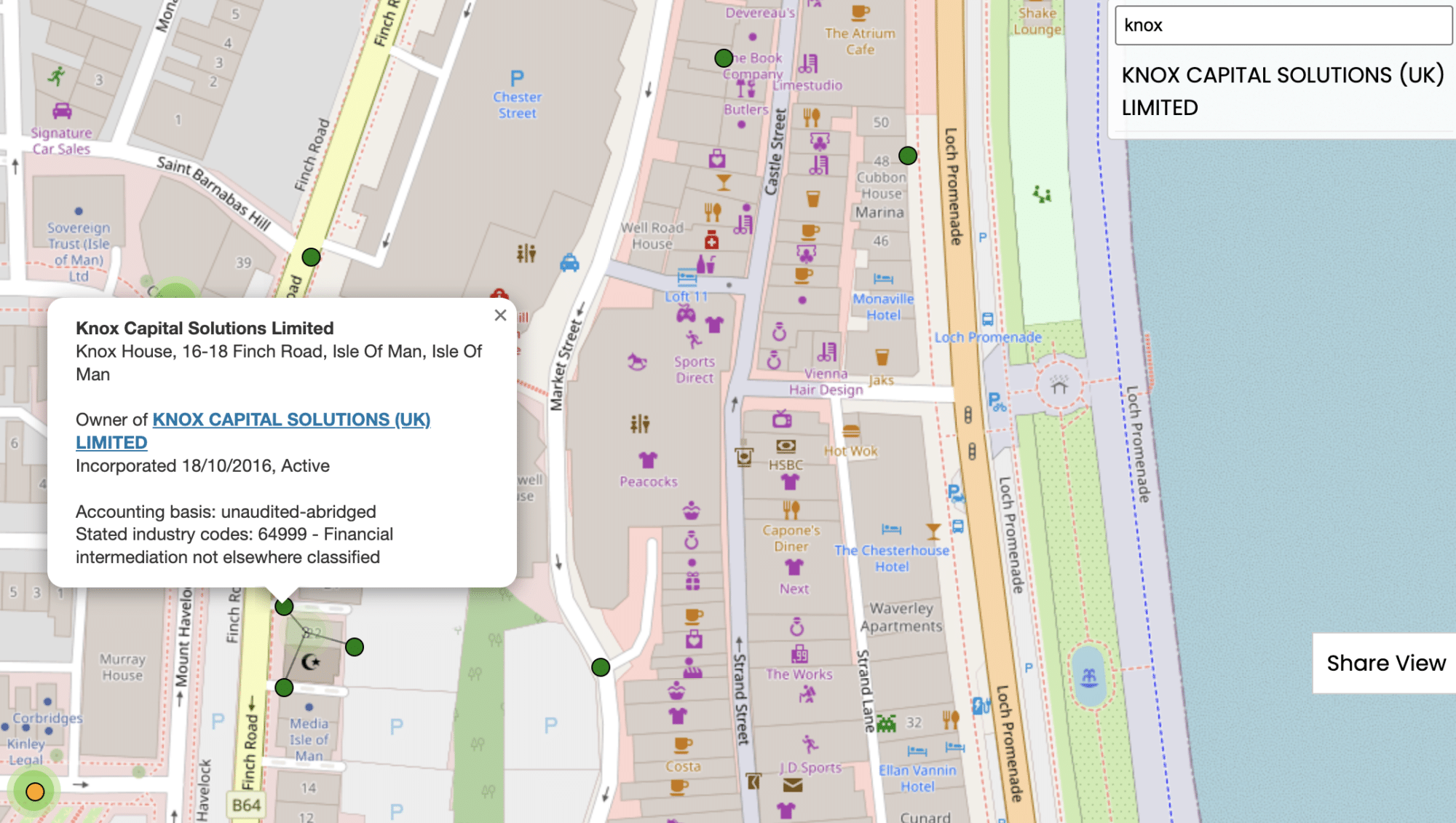

- The increase of tax rates and closing of loopholes in 1974/75 resulted in an boom in tax avoidance schemes, which neither the tax legislation of the time or the doctrines applied by the courts26 were able to counter. The schemes would often convert incomes (taxed at 98%) into capital gains (taxed at 30%)27, magic large tax losses into existence to eliminate tax entirely28, or use “whole-life” insurance policies or other structures to shelter assets from tax. An entire industry arose to sell such schemes and, unlike today, these schemes worked.29

- All of the above were perfectly legal strategies, but another option was to simply break the law and evade tax. The rise of tax havens in the 1970s, most of which guaranteed absolute secrecy, meant that those with cash outside the UK could stash it untaxed into an offshore account, with very little prospect of ever being caught. That isn’t at all the case today.

It is, therefore, a fundamental error to simply compare the statutory tax rates of the 1970s with the statutory tax rates of today – it ignores the reality of how much tax is actually paid.30

What about the 1950s and 1960s?

The 1970s are often described as the highest tax decade, but that’s not quite right – income tax rates in the 1940s and 1960s briefly went over 100%. However the rate of capital gains tax in those years was zero – because there was no UK capital gains tax.

It was, therefore, standard practice for the very wealthy to (without too much effort) convert their income (taxed at very high rates indeed) into capital gains (completely untaxed). An episode of Untaxing discusses the Beatles’ successful use of this strategy, and how the same tricks don’t work today. For a much more detailed exploration of the strategies adopted in the 1950s and early 1960s, I highly recommend the 1962 edition of Titmuss, Income Distribution and Social Change.

So, whilst it’s harder to find information on the tax and income share of the 1% in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, I would be reasonably confident that the 1% paid less tax then than in the 1970s – and much less than today.

Why does it matter?

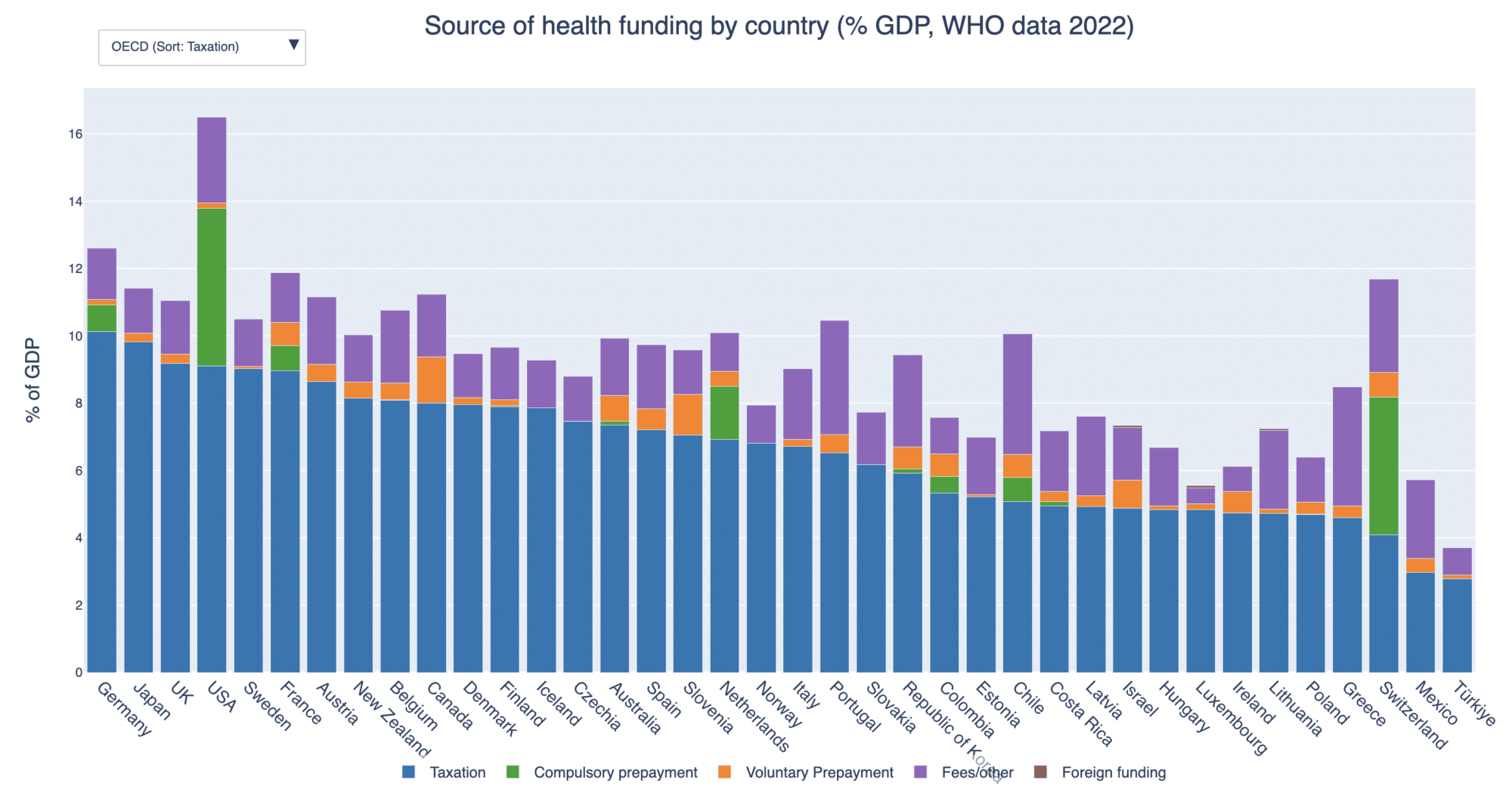

It matters because the tax policies of the 1970s were a failure. They failed to tax the rich effectively. They failed to fix the Government’s fiscal problems.

The lesson of the decades since the 1970s is that the best way to tax the wealthy is by expanding the base and closing loopholes. That makes a less snappy soundbite than sending rates sky-high, but the evidence and the history shows that it’s fairer and much more effective.

Many thanks to all the veterans of the 1970s tax wars who spoke to me, and to T for help with the economic evidence.

The charts and data used to compile them are available in this spreadsheet.

Footnotes

Stevenson is also likely wrong about the link between tax rates/inequality and house prices. To a significant degree, he has it the wrong way round. The cost of housing is a significant driver of inequality, in terms of both income and wealth. The evidence suggests that a number of factors combined to drive up house prices: an increase in demand (more one and two person households), restrictions on supply (planning and lack of space) and (most importantly) a long period of historically low interest rates. The impact of inequality seems much less significant, and the direction of that impact is contested. There is some evidence that absolute (but not relative) inequality somewhat increases house prices. Others have reached the opposite conclusion, particularly over the long term. Possibly the effect is being confounded by credit availability, which impacts both inequality and the housing market at the same time, but in any event the effect is much smaller than the other factors I mentioned above. ↩︎

83% income tax plus 15% investment income surcharge. There’s a common belief that Dennis Healy would have raised the top rate of income tax further, but the effective on investment income would then have been over 100%. ↩︎

Average earning figures are here. I’ve used the figure for average male earnings; average female earnings were 40% lower, but significantly fewer women were in the workplace than today. ↩︎

There’s a table showing how the highest rate fell over time here and another here showing the different bands at the time. Note that there was more movement in the top rate than shown in the chart because, until 1974, there was both income tax and surtax on all income. From 1973 there was instead a higher rate of income tax and a 15% surtax on unearned/investment income – the net effect was that the top marginal rate of tax on employment income fell from 91.25% to 75%, but investment income was taxed at 90%. ↩︎

Rates have also fallen for those on median incomes. The statutory effective rate of national insurance and income tax for someone on median income has almost halved since the 1970s. The effective rate for someone on half of median income is one quarter of what it was in the 1970s. See figures 16 and 17 in this Resolution Foundation paper. There will have been some impact of “perks” and tax relief (particularly mortgage interest relief) to bring down the 1970s effective rate for median and low paid workers, but the use of more structured avoidance tools was of course much less common for workers in these categories than for high earners. ↩︎

For dividends the rate is 39.35%, reflecting the fact that the company profits (from which the dividend was paid) were themselves subject to corporation tax. In the 1970s there was instead a credit: direct comparison between the current dividend rate and the old tax credit regime is not straightforward but in broad terms the credit system was (for UK dividends) somewhat more generous than the current rules. Given the complications I’ll focus on the main rate in this article. ↩︎

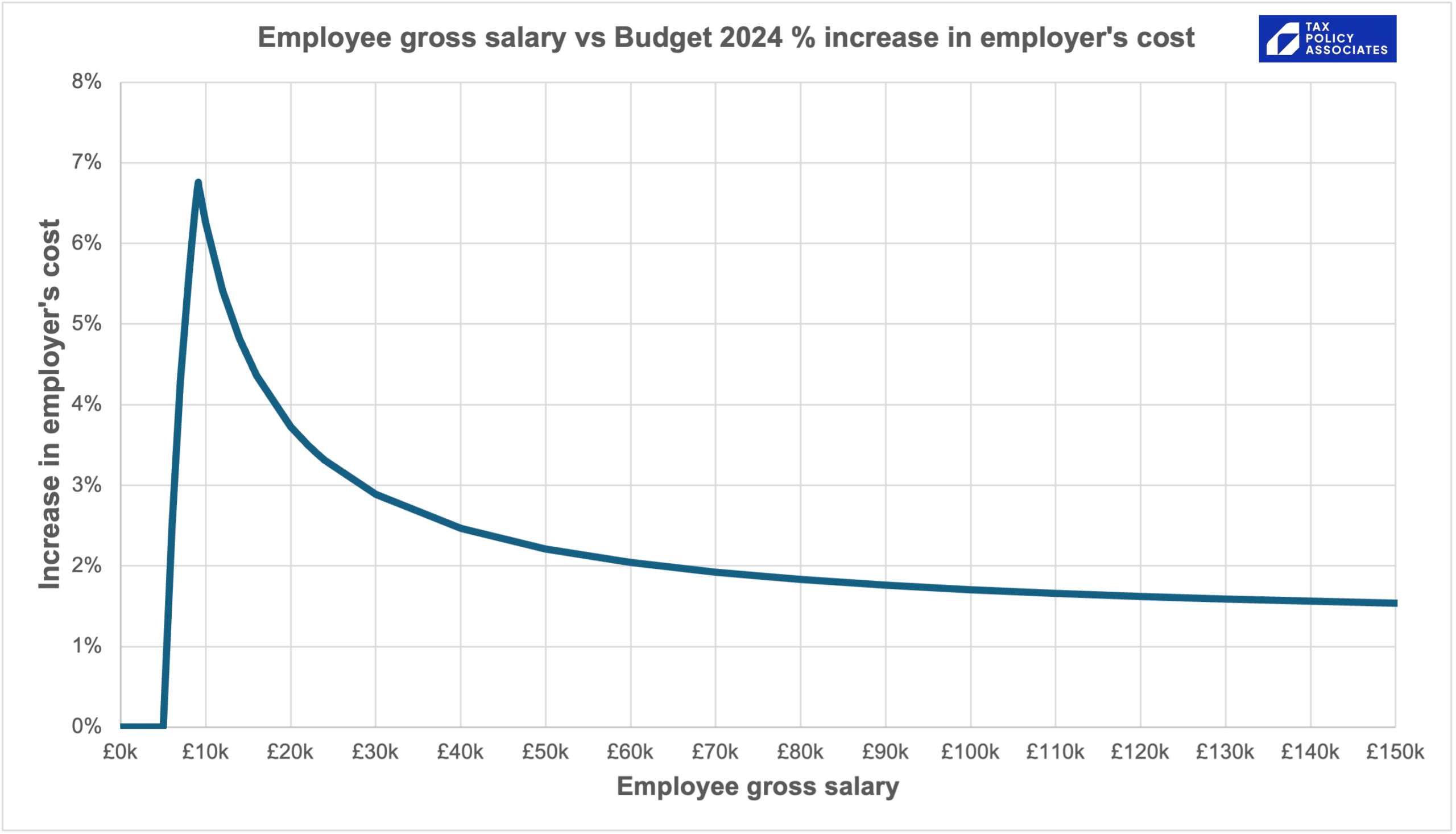

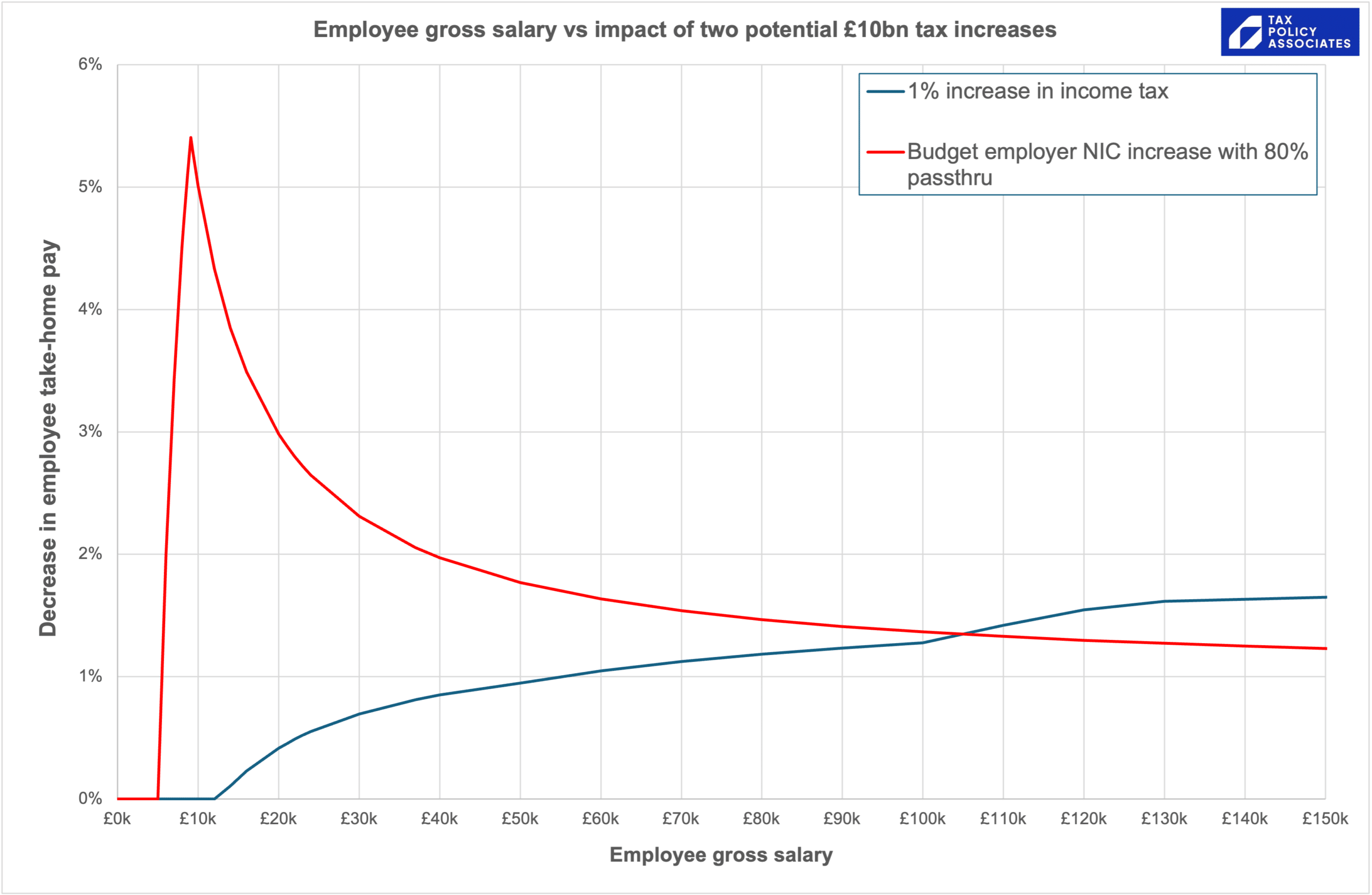

In this article I’m leaving out national insurance; realistically it means the highest marginal rate of tax on employment income is 47% (or 50% in Scotland). In the 1970s there was no employee national insurance past the upper earnings limit. Employer national insurance was 10%, rather than 13.8% in recent times, and 15% now. So national insurance to a small extent defies the overall trend. ↩︎

That’s despite the bump in the latter half of the 1970s, when very high inflation meant fiscal drag had an even greater effect than it has had in recent years. ↩︎

The source for this chart, and other related data, is set out in my previous article on the shape of the UK tax system. There’s another chart on page 6 of this IFS paper covering 1948-1999, which also shows remarkably little change in the total raised by income tax and wealth taxes. ↩︎

Unfortunately I wasn’t able to find any data on the income tax share of the top 1% before 1978. It is in principle possible that it was higher in earlier years/decades, but nobody I’ve spoken to thinks this is plausible. When top tax rates are above 90%, very few people will take their income above that level. ↩︎

Precisely what the correct percentage is and was is highly contested. The IFS has published a very helpful chart (page 14) showing the most well-known estimates, but all have one thing in common: the increase in the income tax paid by of the top 1% outstrips their increased income share (even if we ignore the fact that the rate of tax is dramatically lower). ↩︎

It’s important to note that estimates of income share subject to considerable uncertainties and limitations. One under-discussed element, very relevant to this article, is that the very strategies used by the wealthy to avoid tax took their income out of tax returns and national accounts. The 1% income share estimates for the 1970s, both ONS data and Piketty’s figures, may therefore be significant under-estimates. It was suggested in the 1960s that, for this reason, the apparent decline in the top income shares in the post-war period could be an illusion. There is little evidence for that as an overall proposition, but research into hidden dynastic wealth has found that one third of the apparent fall in the top 10%’s income share may in fact reflect hidden wealth. Piketty falls into the trap of assuming that high apparent tax rates translate into high effective rates, not appreciating that his sources are based on national account statistics which don’t include many common forms of avoidance (see e.g. Bachas page 10, bottom of first paragraph, cited by Piketty on page 584 here). ↩︎

We also need to be careful when using “income” as a proxy for “rich” or “poor”. For example, it’s often said that the very poor pay a higher percentage of their income in tax than the very rich. That’s incorrect – when we drill down into the data we see that this effect is driven by the lowest-earning 1%, who pay 265% of their income in tax. How can anyone be in such a position? Because these people aren’t “poor” at all – they’re some combination of: students, the temporarily unemployed living off savings, and retirees living off savings (plus, possibly, errors in the data). ↩︎

Another point to watch is that a significant number of the 1% come to the UK from abroad, and that fraction has doubled since the 1970s. ↩︎

The explanation for the increase in the income share of the top 1% is well outside my expertise. It’s common to see a simple assertion that the rise in inequality was caused by the drop in tax rates – these claims typically don’t look past statutory tax rates and are therefore hard to take very seriously. There are more sophisticated analyses such as Hope and Lindberg which attempt to include changes in the tax base as well as rates – although (perhaps because of the international nature of the study) the authors don’t appear to realise quite how many tax avoidance strategies there were in the UK. Their approach to estimating effective tax rates (national accounts) should properly take income-to-capital schemes into account, but won’t capture tax avoidance strategies like under-valued perks, circular transactions, loss generation etc. It is therefore likely that Hope and Lindberg over-estimate the effective tax rates of the 1970s, when such arrangements were endemic. And of course there are those who say this was a “Laffer” effect where it was the drop in tax rates that incentivised additional labour supply, increasing incomes. However the evidence suggests that, whilst such effects are very real when tax rates are at high levels, the effect is mostly shifting of income to a taxable form, rather than an increase in actual labour supply). All in all, I find the non-tax explanations to be more persuasive, particularly globalisation, technological change, and the decline of unions. ↩︎

48% in Scotland. ↩︎

The tax base today is much wider/better than in the 1970s, but certainly very flawed. The evidence shows that only one in four of those earning £1m in 2015/16 pays a rate close to the 47% we’d expect (tax plus NI); the average rate of tax paid by that cohort was just 35%. That isn’t down to anything very clever, but simply because capital gains in 2015/16 were taxed at rates as low as 10%. ↩︎

Kaldor, An Expenditure Tax, reviewed here. ↩︎

For example, an employer already owns a mansion. It lets the executive live in the mansion. The employer says it only bears the running costs, and so the cost of the mansion itself isn’t a taxable benefit. Or even further; that it would bear the running costs even if the mansion was empty, so there is no cost to it of letting the executive live in the mansion – and there’s no taxable benefit at all. This kind of planning was commonplace for senior executives. ↩︎

There was also widespread abuse of “expense accounts”, which executives would use for items which realistically should have been taxable benefits, but which the Inland Revenue had great difficulty tracking. ↩︎

As I note above, this means that the cash income and taxable income of executives in the 1970s is not necessarily a good guide to their actual economic resources; the estimate of the 1%’s income share are likely under-estimates. It also means that significant sums of what was realistically remuneration are missing from the national accounts statistics relied on by Piketty and others to estimate effective tax rates – they therefore over-estimate those rates. ↩︎

Until 1960 it was even easier, as compensation for loss of office was entirely tax-free. This wasn’t just used for “golden goodbyes”; directors were often hired on short term contracts and, when each contract expired, a tax-free compensation payment was made and the director was immediately rehired. It was a “cloak for additional remuneration“. ↩︎

See Titmuss, Income Distribution and Social Change, page 134. ↩︎

There’s a fascinating exposeé here of how one of those non-doms, Stanley Kubrick, lobbied to maintain those loopholes. ↩︎

The original draft of this article said 1988. That was a bad typo – my apologies, and thanks to the commentators who pointed this out. ↩︎

At least until the WT Ramsay case in 1982. ↩︎

There’s a good explanation of how “bond-washing” and other income-to-capital schemes worked here. The schemes were more popular before 1965, when there was (broadly speaking) no capital gains tax at all. The incentive to use the schemes diminished subsequently, and further as anti-avoidance schemes were introduced – but they continued through to the equalisation of rates in 1988, and indeed still exist in some forms today. ↩︎

As noted above, such schemes have the incidental effect of eliminating income from the national accounts (because the real income is offset by the artificial losses); these schemes therefore aren’t picked up in the estimates of effective tax rates relied upon by Piketty and others. ↩︎

For anyone interested in the most notorious of the scheme promoters, Rossminster, I highly recommend The History of Tax Avoidance by Nigel Tutt (or its predecessor, Tax Raiders). Out of print now, but second hand copies are often available online, and it’s widely available in libraries. ↩︎

Nevertheless this is a mistake made by eminent economics. The late Tony Atkinson was an eminent scholar of inequality, but he presented a chart of raw changes in headlines rates in Inequality: What Can be Done (Figure 7.1 at the start of Chapter 7), and used this to calculate the “marginal retention rate”. This seems a bad error. ↩︎