At a time when the UK’s finances look fragile, the new Chancellor would be forgiven for thinking the only purpose of changing the tax system is to raise Government funding.

There is, however, another purpose: to fix those elements of the UK tax system which stand in the way of growth and those elements that are desperately unfair. It’s often the same elements.

Everyone involved in the tax system knows that radical tax reform is overdue. As Isaac Delestre puts it, “there are few corners of the British tax system that are not in urgent need of repair.”

Some tax reform is easy and obvious. A lot of it isn’t. And some of the most important tax reforms will take political bravery. But this is a splendid opportunity for a new Chancellor to deliver both equity and economics.

Here are a baker’s dozen suggestions:1

In this report:

- 1. HMRC reform

- 2. No more crazy marginal tax rates

- 3. Stop playing the tax avoidance game

- 4. End penalties for the poor

- 5. Abolish stamp duty on shares

- 6. Tax simplification

- 7. Property tax reform

- 8. End the tax system's bias against employment

- 9. Inheritance tax reform

- 10. Cut the VAT threshold

- 11. Make full expensing real

- 12. Make environmental tax make sense

- 13. Capital gains tax reform

1. HMRC reform

There are too many obvious signs of HMRC failure at the moment. Terrible customer service. A series of unforced procedural errors. Notorious tax avoiders being permitted to make fortunes from ripping off the tax payer for decades.

And there are equal signs of failure in the cases that HMRC do pursue. Bad technical positions with no policy rationale. Penalty appeals involving vulnerable people. HMRC’s Litigation and Settlement Strategy has become an albatross that creates too many impediments in the way of dropping bad cases.

Increased funding is part of the answer, but the problems go much deeper. The Chancellor should bring in people with deep experience of how HMRC used to work, and keen insight into how it could work.2

2. No more crazy marginal tax rates

I had a message yesterday from a consultant anaesthesiologist.

He earns just under £100k – that’s typical for a junior consultant. He currently receives fifteen hours a week of free childcare.

His hospital trust has asked him to work extra hours, for which they pay £125/hour. But there are two problems. First, the personal allowance taper means that he has a marginal rate of 62% on earnings above £100k. Second, If his earnings hit £100k then his eligibility for free childcare disappears.

These factors together mean he’d have to work 61 hours3 to make even £1 of additional net income. So he doesn’t. And many people have a much worse result – the total benefit of the free childcare can be as much as £20,000, and it all disappears at £100k.

There are hundreds of thousands of people in the UK in this position, and we’ve created an incentive for them to avoid work. It’s hard to think of a more anti-growth feature of the tax system.

The problem is that income tax has been damaged by a series of gimmicks, bodges and compromises employed to avoid increasing the rate. And they’re now very hard to remove.

So what should the next Chancellor do?

First of all: own it. Acknowledge that this is how things are, and it’s a problem.

Second: don’t make it worse. Commit to taking no steps that will create further anomalously high marginal rates

Third: plan to end it. Smooth out the rates and, when circumstances permit, abolish them.

3. Stop playing the tax avoidance game

Tax avoidance used to be much like cricket. Teams of brilliant (albeit amoral) lawyers creating fantastically complicated structures which may have been morally questionable, but were legally defensible.

That’s not how it is today. Dodgy boutiques sell doomed schemes, ignore rules requiring disclosure to HMRC, and declare insolvency and walk away when they’re caught. The actual taxpayers are often low paid workers, who don’t realise the schemes they’re signing up to, and end up holding the baby.

That amazing figure that 1/3 of all small business corporation tax isn’t being paid, almost £10bn/year? I think a lot of it isn’t real small businesses – it’s “umbrella company” tax avoidance and tax evasion, and schemes involving people like Barrowman and Baxendale-Walker. We’re talking huge sums of money being essentially stolen from taxpayers.

It’s time to stop treating this as a game.

The Government should scrap the current consultation on regulating the tax profession. Some of the worst offenders are barristers, who are already regulated. And the bad actors who are currently unregulated will either ignore, or game their way round, any new regulations.

The answer isn’t to suffocate the bona fide tax profession in red tape. It’s to come down extremely hard on the cowboys, so their business ceases to be economic.

Some mixture of:

- Criminalising the failure to disclose a tax avoidance scheme to HMRC under DOTAS. That means a criminal offence for the individuals directly involved, as well as the companies, their directors, and advisers and other facilitators. This should be accompanied by financial penalties geared to the tax at stake. With a statutory defence to the offence and the penalties where a person took reasonable steps to ensure compliance, but the rules were breached due to circumstances outside their control.

- Ending legal professional privilege for advice provided as part of a tax avoidance scheme which should have been disclosed under DOTAS, but wasn’t, and for schemes where the general anti-abuse rule applies. Too many barristers are hiding behind the pretence they are neutral advisers when what they’re really doing is enabling quasi-criminal behaviour.

- A renewal of the Government threat in 2004 to counter disclosed tax avoidance schemes with retrospective legislation. That shouldn’t be like the loan charge – introduced 10 years too late, after the problem had ballooned out of control. Instead, each disclosed tax scheme should trigger a fast determination: can this be easily countered with existing laws and powers? Or is a new retrospective rule required? The timescale should be weeks, not months or years.

- A properly staffed HMRC investigation unit to ensure new and old rules targeting avoidance and enablers are actually used.

All of this needs to be calibrated carefully, so it has no effect on bona fide tax advisers, but it drives the cowboys out of business.

4. End penalties for the poor

Over the last four years, HMRC charged 420,000 penalties on people with incomes too low to owe any tax. They shouldn’t have been required to file a tax return, but for some reason they were – and because they didn’t file on time, they received a penalty of at least £100. In most cases, that’s more than half their weekly income.

Astonishingly, 40% of all late filing penalties charged by HMRC over these four years fall into this category.

And penalties can go much higher than £100. TaxAid reports on Emma, who earned less than £6,000 per year, but paid HMRC penalties of £4,700.

The cause of this travesty is a change of law in 2011. Until then, a late filing penalty would be cancelled if, once a tax return was filed, there was no tax to pay. However the law was changed, and now the penalty will remain even if it turns out the “taxpayer” has no taxable income, and no tax liability. At the time, the Low Incomes Tax Reform Group warned of the hardship this could create, but they were ignored.4

The law should go back to how it was. Nobody filing late should be required to pay a penalty that exceeds the tax they owe. And HMRC needs to think carefully about how to improve tax compliance from the poorest in society without creating an unfair burden on them.

5. Abolish stamp duty on shares

A great deal of ink has been spilled on the underperformance of the FTSE. Not enough has been written about the role of stamp duty. At 0.5% it’s the highest such tax in any large developed country.5 It increases the cost of capital for business, particularly on projects that are already marginal. It’s easily avoided by professional investors using CFDs. There’s a good case that abolition would boost GDP and perhaps even pay for itself.

Instead of creating complex new subsidies for the UK market, like the “British ISA“, it would be better to remove the complex existing barrier created by stamp duty.

If only Nixon can go to China, perhaps only a Labour Chancellor can abolish stamp duty.

6. Tax simplification

Tax is too complicated, particularly corporate tax. It deters investment, and misallocates resources (too many tax lawyers!).

Nigel Lawson famously abolished one tax in every budget. The next Chancellor should take that as a starting point, and abolish one tax, or major tax rule, every Budget. Here’s a starting point:

- Abolish old fashioned stamp duty – the one with actual stamps. It serves no purpose now we have proper taxes on securities and real estate. It’s a deterrence to using English law.

- Abolish bearer instrument duty – very few people even know it exists, and when I asked HMRC, they were unable to identify any time in recent history it had actually applied.

- Abolish the bank levy and roll into the bank surcharge.

- Abolish historic complexity. Methodically go through tax legislation and abolish the legions of anti-avoidance rules that were once necessary but now aren’t. In the modern world, the courts are deeply hostile to tax avoidance, every tax rule has a specific targeted anti-avoidance rule, and there’s a general anti-abuse rule on top. I’m confident hundreds of pages of historic legislation could be abolished overnight. And, just to be safe, this should be accompanied by blood-curdling threats of retrospective legislation if anyone were foolish enough to take simplification as a licence to resuscitate tax avoidance schemes.

7. Property tax reform

The UK’s main three land taxes are no longer fit for purpose:

- Stamp duty land tax is rightly unpopular. SDLT reduces labour mobility, results in inefficient use of land, and plausibly holds back economic growth.

- Council tax is unfair. It’s now farcically based on 1991 valuations. The low maximum rate means that Buckingham Palace pays less council tax than a semi in Blackpool.

- Business rates are hated, and blamed for the destruction of the high street. Labour’s already committed to replace it.

We can scrap all three taxes, and replace them with a modern, fair, tax on the value of land. A tax that creates a positive incentive to develop land. That’s land value tax – and it has support from economists and think tanks right across the political spectrum.

How many other ideas are backed by the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Adam Smith Institute, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the New Economics Foundation, the Resolution Foundation, the Fabian Society, the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and the chief economics correspondent at the FT?

A new government with a hefty majority has the chance to do something truly radical, both pro-fairness and pro-growth.

8. End the tax system’s bias against employment

One of Jeremy Hunt’s best and most principled moves was to start to phase out employee national insurance.

There was once a real link between national insurance and pension benefits – but national insurance is now just a tax on income with added accounting.

It is, however, a very regressive tax on income, because it applies to employment and self-employment income, but not to rental income, dividends on shares and other forms of passive income.

The answer is to abolish employee national insurance. That’s expensive, so (absent magical tax windfalls) it should be paid for by increasing income tax. And the broader base of income tax means that national insurance can go down by more than income tax goes up. Everyone making their money from their job will be a winner.

That still leaves employer national insurance.

This is a hard problem, but an important one.

Employer NI, at 13.8%, creates a massive difference between the cost of employing someone and the cost of engaging an independent contractor. This means that the thin – and ultimately fictional – line between employment and self-employment becomes hugely important. Complex rules are created to guard the line. HMRC’s efforts to police it waste their time and that of taxpayers. And there remains plenty of avoidance and evasion.

In the long term, the burden of employer national insurance falls on employees in the form of lower wages. But that’s in the long term. If employer national insurance was abolished overnight it would cost £100bn – and in the short-to-medium term that’s just a windfall for employers.

The question is whether there’s a way to abolish employer national insurance, force the benefit to be passed to employees and then tax the employees. It’s not at all obvious how this could be done, but there would be a substantial prize for achieving it.

9. Inheritance tax reform

Inheritance tax is deservedly unpopular. The rate, at 40%, is one of the highest in the developed world. The burden falls on the upper middle class. The very wealthy easily escape it:

And the loopholes used by the wealthy are economically distortive, encouraging unproductive investment in assets like woodlands.

The answer: end the loopholes and cut the rate. We should be more like Germany, which raises a comparable amount despite having a rate of 30%.

10. Cut the VAT threshold

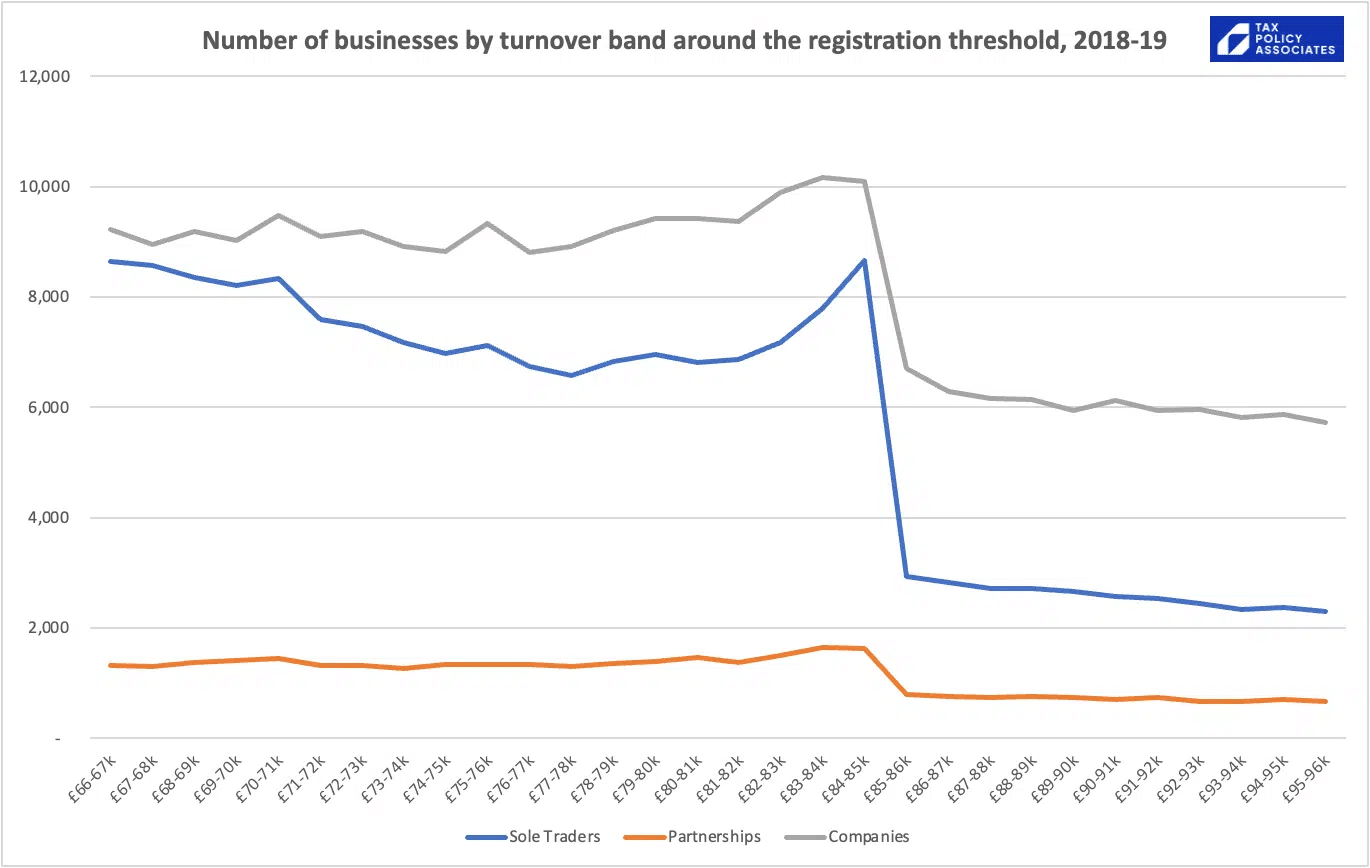

VAT is inefficient. The exemptions and zero rates are too broad, causing uncertainty for business and disproportionately benefiting the wealthy. The flat rate scheme is being widely abused by criminals. And, worst of all, the VAT threshold is too high, and that stops small businesses from growing:

Reducing the VAT threshold will be politically difficult. But there is support across the political spectrum – the Adam Smith Institute says “the case for reducing the VAT registration threshold is overwhelming”. It would have to be combined with a push to enable better app-based VAT compliance for micro businesses.

And revenues should be ploughed into reducing the rate for everybody, to clearly demonstrate this is about doing what’s right for growth, not a Government tax grab.

11. Make full expensing real

Anther Jeremy Hunt success was “full expensing” – letting businesses deduct the cost of investment expenditure up-front, rather than over years or decades.

UK business investment is the lowest in the G7 and the third-lowest in the OECD. Full-expensing can help change that. The Tax Foundation has found that full expensing raises long-run GDP by 0.9 percent, investment by 1.5 percent, and wages by 0.8 percent. These are not numbers to be sniffed at.

But the UK’s “full expensing” isn’t quite full expensing. It doesn’t apply to all forms of business investment – that means we get uncertainty and tax avoidance at the margins, and the full benefit of full expensing is not being unlocked.

The answer is to abandon the complex rules on what kind of investment gets tax relief, and give tax relief for everything. That can boost investment and eliminate a huge source of tax system complexity. But that has to come with a quid pro quo. As the IFS has said, to afford this, and have a system that doesn’t encourage unprofitable investment, we also have to revisit the deductibility of interest.

That’s a radical step, but one that may receive support from a significant proportion of the business community.

12. Make environmental tax make sense

Our environmental taxes are a muddled mess. There’s an economic consensus across the political spectrum in favour of a carbon tax. This is hard to do unilaterally, but the UK could play an important role advocating for a carbon tax in current OECD discussions.

Why isn’t it?

13. Capital gains tax reform

Capital gains tax is broken. If you magically convert income into capital gains then you’re taxed on what is realistically income at the low rate of 20%. If, on the other hand, you invest patiently for years, you’re taxed on your notional return at 20%. Most of that may be inflation – it’s not gain at all. So the effective rate on your actual gain may be much higher than 20%.

We used to have an allowance for inflation. Gordon Brown abolished that, supposedly because inflation allowance was too complex to calculate. But in the internet age where almost nobody enters a tax return by hand, this is no longer an issue.

So we can fix the incentives, which are currently completely the wrong way round. As the IFS puts it: “the biggest giveaways go to those who make big profits without investing much money”.

The answer? Raise the rate of capital gains tax whilst also creating an allowance for inflation. And given that the new rate will apply to historic gains, the new inflation allowance should too. Long term investors will benefit.

Photo by Nick Kane on Unsplash

Footnotes

Originally there were two number 10s. As they say, there are three types of lawyers: those that can count, and those that can’t. ↩︎

To be clear: I do not mean me. I have no knowledge or experience of HMRC and Government, and I would be the wrong person. ↩︎

In that tax year; more if it’s split across two years! ↩︎

See paragraph 4.4.1 of their response to the 2008 HMRC consultation paper on penalties ↩︎

Thanks to the commentator below who pointed out that the Irish rate is 1% – but given the relatively small Irish public market, the two effect of the two taxes isn’t in practice comparable. ↩︎

26 responses to “A tax reform agenda for tomorrow’s Chancellor”

Why not amalgamate NI and income tax as one citizens tax for all – employers NI becomes a direct contribution to a workers personal pension.

Ah Indexation of Capital Gains – happy memories !!

I still have a copy of Tolley’s ‘Capital Gains Tax Base Date Prices 31st March 1982’. Carefully retained in case it came in useful one day.

Of course indexation of gains in corporation tax was frozen at Jan 2018, not that long ago.

Why were you not involved with the so called Office for Tax Simplification which to my mind achieved absolutely zilch as the number of pages in our tax code most be amongst the largest in the world now. All thanks to meddlesome Chancellors (worst examples being Brown and Osborne). Is there any hope that a future Government will listen to this common sense?

Lots of good sense here… but

i shift from NIC’s to income tax will have to be done very slowly.

ii. Property tax reform…. as a result of house price bubble esp in the South there are too many asset rich cash poor people for this bit of think tank wonkery one to work.

iii. Surprised you didint touch on pension contriibutions… £60k pa with full relief at marginal rate and no LTA ….puhlease!

CGT indexation is absolutely the right way to go. Without it, it is impossible to tell what rate of tax someone will be paying in real terms or indeed whether they have made a gain at all. One respondent’s comparison with salaries is not valid, since salaries are earned and paid now rather than paid in one lump after 10 or 20 years.

If only.

Certainly much food for thought here. I’d expect the new gov to look at all of these suggestions, and many others over the next couple of years. The idea I particularly like is indexation of allowances to CPI inflation as part of a more general approach to indexation of pay, benefits, and energy prices.

Why don’t we just tax capital gains to income tax…and get rid of many degrees f the exemptions ( entrepreneurs relief for example).

defensible to do that plus indexation, but it would still give us one of the highest rates in the world.

Are you superstitious, Dan? Wondering if the two 10’s are to avoid a total count of 13? 😉

Thank you, as always, for your thoughts. Very glad you included suggestion 4 – didn’t realise this was happening and feels like a no-brainer to reverse!

thank you!

(Can I get away with claiming it was a deliberate test?)

I just have to object to indexation allowance for CG. It seems like a reasonable position at first blush but we do not have an indexation allowance for salary or profits. What is the justification for treating these things differently. We all get taxed on income created by inflation so either index everything in the tax code or nothing

There used to be an element of indexation with regard to income due to the annual increase in the personal allowance. It may have been small but it was there.

I agree with much of this, but it feels a bit like a shotgun approach.

I would like any new government to set out a roadmap on how they plan to change the structure of the tax system over the next five to ten years. They should consult on it before adopting it. They might need several roadmaps (e.g. for corporate tax, personal tax, etc). This would allow any Chancellor, at a loss for something to say in a Budget, to look at the roadmap rather than come up with some ill-thought-out pet tax idea (I’m looking at you, Mr Osborne).

I agree about resurrecting Dawn Primarolo’s statement. But I don’t think it will change anything but the edge. The dodgy promoters will continue to promote their dodgy schemes as they don’t care. Hence, I agree with you about using the criminal regime that ups the ante when a dodgy promoter goes through Heathrow.

I disagree about getting rid of TAARs, but I may be reading too much into what you say. Obviously, those no longer relevant should go, but no more. I also have no issue with making the wording more similar between TAARs to make them easier to understand. But I think it would be silly to rely on the current version of the GAAR (and I’m not sure that you are actually saying that).

The current GAAR process takes a very long time, and there are few published cases (only 26 or so have been published so far). The last published opinion was dated 20 January 2023, and the event it discusses happened around 2018 or so. How long did it take HMRC to think “GAAR!” to get permission to raise “GAAR”, to get all the notices out, and representations in, before the panel gives an opinion? It’s not a quick process. TAARs are much quicker.

Also, the GAAR panel is not a fact-finding body. So if a taxpayer’s motivation is key as to whether something is abusive or not, that’s not suitable for the current GAAR.

*** regenerate response *** 😉

Excellent suggestions.

My only query is on #7 – Council tax does have anomalies when looked at on a national level but it is also a local tax set at a level based on the needs in each local authority area. Do you envisage that a land value tax would also be set and collected locally? A system where each local authority had the power to tax land value would do much for local government accountability and empowerment.

I’m not sure how the local element would work. The problem is that, on the face of it, Kensington & Chelsea could have a rate 1/10th of e.g. Bolton – but that undoes the whole point of the tax.

I agree in terms of a land value tax that it would need to be applied on the same basis across the country but council tax is local at the moment albeit not the sole source of revenue for local authorities.

Removing a local tax and replacing it with a national tax would require a different approach to local government financing. As it currently stands precepting authorities set their council tax levels based on their budget needs and subject to the political constraints of their local electorate. I’m not sure HMT would be comfortable with such uncontrolled demands on a land value tax.

Dan

Please can we start a national grass-roots campaign to reform property tax? On the lines of the Anti-Corn Law League of 1840s. It’s mad for people to say that Council Tax is OK, as if eventually all other rich countries will adopt it. And to say too many cash poor, asset-rich peaople in UK to return to the ad valorem system we invented in 1871 and abandoned in 1991. These people should start by reading ‘US Property Tax’ in Wikipedia and then try to explain why the USA has got it all wrong and needs Council Tax instead.

Blair not reversing the change in 1997 is unforgiveable.

I don’t think the phrase “income tax can go down by more than national insurance goes up” is what is intended. Apologies if I’m missing something.

if you take 1% off NI it means less X less tax rasied. Iyou want to replace that X ammount by increasing income tax you add less than 1% as it has more streams in scope.

I think the consultant example should be 30 hours of free childcare. That one gets cut off, everyone get 15 regardless of income.

I believe it all goes? See e.g. https://www.gov.uk/check-eligible-free-childcare-if-youre-working#:~:text=If%20you%20or%20your%20partner%20have%20an%20expected%20adjusted%20net%20income%20over%20%C2%A3100%2C000%20in%20the%20current%20tax%20year%2C%20you%20will%20not%20be%20eligible.

Excellent piece.

Just commenting on the points I can relate to as a former Inland Revenue and HMRC compliance officer.

1. The main problem is staffing, the closure of local offices resulting in considerable experience being lost, the centralised offices have resulted in the wrong people being recruited and even worse the wrong type of people being promoted. When Lyn Homer put forward her plan to close offices she was told of the problems but as was her way she just ignored them.

2. The problem with penalties has mostly happened also after the closure of local enquiry centres, the experienced staff of these knew their locality and their customers.

All the closure did was alinate a large segment of the community that needed them. Phonelines and webcat do not came anyway near providing a good enough service for the disadvantaged. Once Inspectors were expected to go to help individuals get things right on IRECS (Inland Revenue Enquiry Centres). I wonder if the current crop have ever helped to get a taxpayer face to face.

3. Simplification, yes the only people who benefit are the top end accountants/tax avoider promotors and the lawyers.

ex IR and HMRC accounts investigator. I just love your comments. I can so identify with them. Everything in point 1 is correct. Dan’s point 1 final para is just spot on. I watched it go downhill from the early 2000’s. As an Inspector I did my rota day on technical callers at the counter, which were usually accounts or CGT queries. It didn’t take long, the public were grateful, it got them on the right track and, rather surprisingly, HMRC had a reasonable reputation and the public liked the service we provided. It is unbelievable how one government dept. can have managed to be so successful in alienating just about all sections of the public and professions!

They were told so many times how wrong it was all going but no one listened. We were managed by people who had no knowledge of taxation or accounts. The only thing my manager was capable of was signing my leave sheet. She was in charge of a group of accounts investigators and had never seen a set of accounts in her life. How on earth can you manage in that way.

Prior to when the rot set in we were managed by managers who had been promoted from having good investigation results. So they were able to pass on knowledge and expertise. Training in the early years was excellent. By the time I left training had slipped so badly. Simple book keeping exercises were multiple choice. Unbelievable.

I cannot see any way of going back to getting the calibre/training and competence of investigation inspectors very easily. Sadly all that seems to be lost. So is the potential yield they could bring in. If HMRC/the new Labour govt just went after the evasion problem it would bring in so much.

Apologies for the rant, Dan, but after my whole career working there the state of HMRC is just so very sad.

“ At 0.5% it’s the highest such tax in any developed country.” ahem. Irish stamp duty is 1%😀

OMG – corrected!