A small number of KCs and junior barristers are enabling large-scale tax fraud. They do it by providing tax opinions backing schemes designed to “avoid” tax on wages paid to contractors. The schemes have no real technical basis, but the promoters behind the schemes use the opinions as a badge of credibility – and, more importantly, as a shield. When HMRC shuts a scheme down, the promoters point to the KC’s advice, making any criminal prosecution difficult or even impossible.

In reality, these schemes have no realistic prospect of success. All the KC opinions we’ve seen on these schemes rest on assumptions that are plainly untrue, ignore basic principles of tax law, and don’t bother to address statutory rules designed to stop exactly this kind of arrangement. The opinions aren’t there to be right, and aren’t really legal advice at all – they’re just cover.

This report analyses a new case involving one of these schemes, “Purity”. It was backed by a KC opinion – but the scheme was hopeless. None of the remuneration tax specialists we spoke to thought it had any prospect of success. One respected senior tax KC (not involved in these schemes) described the Purity scheme as “incompetent and impossible”. A senior tax lawyer specialising in remuneration tax told us the scheme was “unbelievably bad”. Yet a KC – identity currently unknown – provided an opinion that the scheme worked. Just as KCs have done for the dozens of prior contractor schemes.

The contractors using the schemes never see the KC’s opinion. They usually don’t even realise they are avoiding tax – they’re presented with complex and often deliberately opaque documents to sign, and never told what’s going on. If they were told what was really going on, most of them would walk away.

The whole business is corrupt. It plausibly costs the UK £1bn+ in “avoided” tax and leaves workers facing liabilities they neither understood nor expected. The KCs are facilitating what is realistically tax fraud, and what they should know involves the deception of the individual contractors.

The behaviour of this handful of KCs has been public knowledge for at least fourteen years, but nothing has been done. It’s time for the Bar to confront the small number of rogue barristers whose false tax opinions are enabling fraud. And if the Bar won’t act, Parliament should.

In this report:

The Purity scheme

A High Court judgment was published just before Christmas which encapsulates the problem. It concerns an “umbrella company” called Purity Limited.

Umbrella companies

Before the 2000s, people wanting to undertake agency work signed up to a recruitment agency. These days, for reasons that are not entirely clear1, many recruitment agencies have no workers on their books. Instead, the workers are hired by an “umbrella company”, each of which has hundreds or thousands of employees. The end user will be a legitimate business (say Tesco). When Tesco wants to hire temporary workers, it approaches a recruitment company. The recruitment company then asks an array of umbrella companies to bid to provide workers, and usually picks the umbrella company that provided the lowest bid. The umbrella then sorts out admin, and applies PAYE income tax/national insurance.

Here’s how that umbrella company should work:

- From Umbrella Co. to Worker (Label: Net salary)

- From Recruitment agency to Umbrella Co. (Label: Fees)

- From End User to Recruitment agency (Label: Fees)

- From Umbrella Co. to HMRC (Label: PAYE tax & NI)

There’s nothing improper about this structure; but the incentives the whole setup creates are inherently dangerous. The reason: the bidding process. There should in theory be little difference between the bids the various umbrella companies put in to the recruitment company: each umbrella company is paying market wages (often minimum wage), operating PAYE, and has administrative costs and wishes to make a profit. There is not much room for one company to underbid another – there’s only so far administration and costs can be squeezed.

But there is another way: don’t pay the tax. In some cases it’s just simple fraud: the umbrella companies invoice the recruitment company for the wages plus tax, pay the wages to the employees, and never pay the PAYE tax to HMRC:

- From Umbrella Co. to Worker (Label: net salary)

- From Recruitment agency to Umbrella Co. (Label: Lower fees)

- From End User to Recruitment agency (Label: Lower fees)

- From Umbrella Co. to HMRC (Label: No tax paid)

They win the bid, and run off with the money. But it’s a high risk endeavour – if caught, prosecution and jail are likely outcomes.

So a much smarter way to commit fraud is to dress it up as tax avoidance. Claim to have a structure that means that the employees’ remuneration isn’t taxed, and so you can lawfully not pay the PAYE tax to HMRC. The same result as the simple fraud, but with the distinct advantage that, when you’re caught, you can say it’s only a civil tax dispute.

The end user (e.g. Tesco) will have no idea this is going on, and increasing businesses are taking steps to try to police their supply chain – but it’s not straightforward.

The scheme

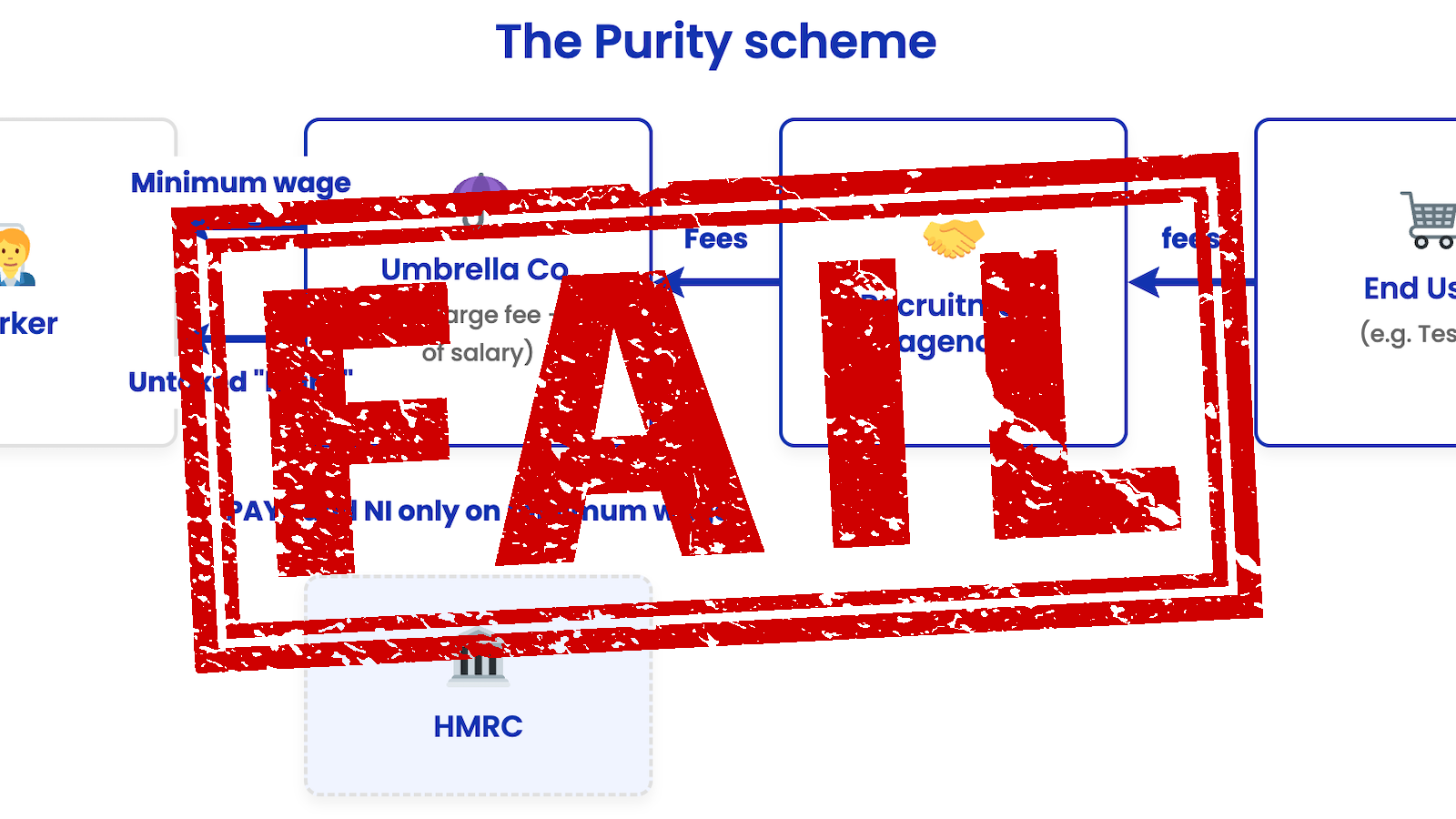

The Purity scheme worked like this:

- Purity had about 700 workers on its books.2

- These were highly paid workers – about £50/hour (so around £100k/year).

- 10% of the workers were paid normally.

- The rest were paid the minimum wage as a salary; the rest of their remuneration was provided as a “loan” from Purity.3 The claim was that the loan wasn’t taxable; therefore significant tax and national insurance was saved – about £30k per worker per year. Around half of that “tax saving” was retained by Purity as a fee; some of it went to the workers (it’s unclear how much); it’s likely some of it was passed to the recruitment agency that hired Purity, i.e. with Purity charging a lower rate for the worker that it otherwise would.

- Purity paid part of its earnings into a Dubai-based pooled investment scheme – the idea was that investment returns would take this to a point where employees’ loans could be repaid (although application of scheme funds for this purpose was discretionary).

In other words:

- From Umbrella Co. to Worker (Label: Minimum wage)

- From Umbrella Co. to Worker (Label: Untaxed "loans")

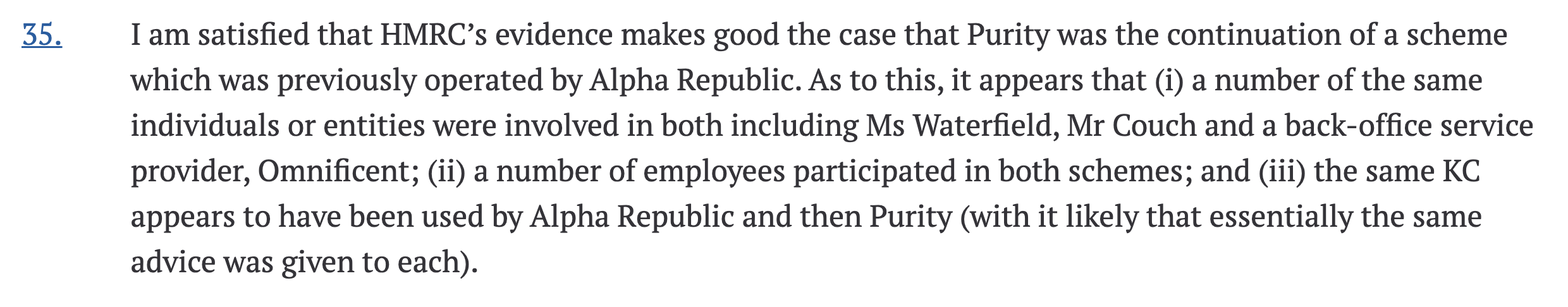

- From Umbrella Co. to Dubai fund (Label: £ to invest)

- From Recruitment agency to Umbrella Co. (Label: Fees)

- From End User to Recruitment agency (Label: fees)

- From Umbrella Co. to HMRC (Label: PAYE and NI only on minimum wage)

The consequences

None of the remuneration tax specialists we spoke to thought it had any prospect of success, for these key reasons:

- The employees could choose whether or not to take their remuneration in the form of a “loan”. If an employee is entitled to the full amount as earnings, and merely elects to receive part of it in another form, the amount remains earnings from employment. So this was straightforwardly remuneration. 4 No further analysis is required.

- The structure doesn’t make any sense. No rational employee would agree that, instead of being paid by their employer, they take a loan, regardless of what extra-contractual assurances are made about the unlikelihood of the loan being called (and a “discretionary” fund that might or might not help repay the loan would not be very reassuring).5 Hence the “loans” can’t, realistically, have been loans at all. Either the arrangement was a sham or the “loans” were, in substance, remuneration.

- The investment scheme introduces an additional tax problem: the “disguised remuneration” rules likely apply both at the point money is placed into the fund, and the point it’s applied for the benefit of the employees. In reality, HMRC had no need to apply the disguised remuneration rules, because the remuneration was taxable on general principles (and there’s a rule that generally prevents a double charge). But in the (highly implausible) scenario where the scheme worked and the investment fund was correctly funded/structured, there would be both up-front tax (on the initial contribution to the investment fund) and tax when funds were distributed to employees.

- Since 2013, the UK has had a “general anti-abuse rule” – the GAAR. The GAAR applies only where a scheme can’t reasonably be regarded as a reasonable course of action to take – the “double reasonableness test“. The GAAR has in practice never been applied by a court or tribunal, because almost every tax avoidance scheme of the last 20 years has failed in the courts on the basis of specific tax rules or general principles.6 However, in the very unlikely event that the Purity scheme survived the problems above, we expect that it would be countered by the GAAR.78

- The scheme was required to be disclosed to HMRC under “DOTAS” – rules requiring that avoidance schemes are disclosed at an early stage to HMRC, so that they can counter them. Purity simply ignored DOTAS. We can see no proper basis for this.

One respected senior tax KC (not involved in these schemes) described the Purity structure as “incompetent and impossible”. A senior tax lawyer specialising in remuneration tax told us it was “unbelievably bad”.

We are therefore not in the traditional tax avoidance scheme territory of an attempt to find a loophole. The structure simply fails. What’s more, it involves deception – the “loans” that were not really loans. This raises the question as to whether what’s going on was really tax fraud (“cheating the revenue“).

Other elements of the structure suggest criminal offences may have been committed.

- Employees were misled or misinformed about the nature of the arrangements (presumably because they would have been alarmed if they’d realised that, whatever assurances they were being given, they’d be in serious financial/legal jeopardy when the loans fell to be repaid). It is a criminal offence to intentionally and dishonestly make a false representation with the intention of making a gain.

- The sole shareholder of Purity claimed she didn’t know she was a shareholder. If that’s true, then somebody may have filed a false document with Companies House, a criminal offence. If not true, the shareholder may have committed perjury.

- Under FSMA and The Regulated Activities Order 2001, it is prohibited for an unregulated person (in the course of their business) to make loans to individuals, other than for the purposes of those individuals’ businesses. These were not business loans (they were remuneration for work; a different thing).9 The likely consequence is that the “loans” were unenforceable10 and that Purity and the individuals running it committed a criminal offence.

- The investment scheme could never have repaid the loans. Purity made £45m of loans in one year but had contributed only £470k to the investment scheme. There was no realistic prospect that investment returns would enable the scheme to eventually repay the loans. The employees were misled.

- The Dubai arrangement was likely contrary to FSMA, as we expect it was an unauthorised collective investment scheme.11 Purity was establishing/operating a collective investment scheme, a regulated activity under the Regulated Activities Order 2001. Purity had no FCA authorisation, and so breached the general prohibition in s19 FSMA, exposing those responsible to criminal liability under s23 FSMA. Promoting the scheme to UK workers was also unlawful.

All of this suggests to us that the Purity structure was dishonest in its design and implementation.

But, according to the Purity High Court judgment, Purity was advised by a KC:

We understand that the people behind Purity received a KC opinion confirming that the scheme worked – despite everything suggesting that it wouldn’t. In our view, that opinion was false.

The KC opinion

We don’t believe any reasonable tax adviser would think this scheme works. Indeed any reasonable tax adviser would know that any remuneration scheme of this nature would fail. As tax barrister Patrick Cannon says, it was clear to advisers from (at the latest) 2010 that anyone engaging in a disguised remuneration scheme would be acting contrary to the intention of Parliament (and that rarely ends well). HMRC said back in 2017 that HMRC would challenge users of these schemes, investigate their affairs and apply the GAAR.

So how could a KC provide an opinion backing the structure?

We haven’t seen the Purity opinion, but the opinions we have seen have all followed this approach:

- Make unrealistic assumptions that eliminate the rules/principles that would otherwise undo the scheme. For example, the KC could assume that the loans have real substance and the parties expect them to be repaid (via the investment fund). Any experienced lawyer should know this cannot be the case: no rational employee would replace normal remuneration with a loan they’re required to repay, with vague assurances about future discretionary payments from an investment fund they know nothing about. A moment’s thought reveals that properly funding the investment scheme would require more cash than Purity had.12

- Ignore tax principles which would defeat the scheme. Over time, and particularly since the early 2000s, the courts adopted a purposive approach to the interpretation of tax statutes. As a result, almost no13 tax avoidance schemes have prevailed in court in the last 20 years. The avoidance scheme opinions we’ve reviewed deal with this by simply not mentioning the courts’ modern approach to construing tax statutes.

- Take extremely technical and narrow approaches to interpreting the relevant tax rules – a task made much easier by ignoring the way in which courts actually approach statutory construction.

- Ignore other tax rules that might apply: for example the GAAR or DOTAS.

- Ignore the potential fraud of third parties involved in the scheme. The KC would surely know that an employee who fully understood the loan would not enter into the arrangement. The KC should have realised the investment scheme would not be properly funded. The obvious conclusion: the scheme users were being misled.

You can see an example of such an opinion in our investigation of a different umbrella scheme backed by an opinion from Giles Goodfellow KC.14 That scheme was, in a different way, just as outrageous as the scheme here, with unrealistic assumptions, no analysis of caselaw or inconvenient rules, and it also involved putting unrepresented individuals in legal and tax jeopardy.

These opinions are “false” in the sense that, if the scheme comes before a court, it will almost certainly fail. The KC surely knows this, given the history of tax avoidance schemes in the last 20 years.

Most lawyers go out of their way to not issue incorrect opinions. Quite aside from ethics and professional pride, there are obvious adverse consequences: an angry client, and potentially a negligence claim. However a scheme promoter is very unlikely to be angry when their scheme fails – they expected it. The opinion was for a very specific purpose: to provide cover against the possibility of criminal prosecution.

So do these KCs issue false opinions?

This is a psychological rather than legal question, but in our view it’s a mixture of bad incentives (fees for issuing the opinion; no downside when the opinion turns out to be wrong)15 and arrogance (“my view of the law is correct; the courts just keep getting it wrong”).

Chartered accountants, chartered tax advisers and solicitors are prohibited from facilitating abusive tax avoidance schemes, because their regulators require them to adhere to the Professional Conduct in Relation To Taxation (PCRT). Barristers are not. This is an anomaly it is hard to justify. However, it means that the small number of barristers16 issuing these false opinions believe they are untouchable.

How do the promoters respond?

There are very few cases of umbrella companies, or indeed anyone, defending their scheme before a tribunal. The users of the scheme generally rely on the promoter to liaise with HMRC, and their aim is to delay and frustrate HMRC, not to provide substantive responses. What tends to happen is that HMRC issue a “stop notice” and/or a DOTAS notice, and the companies respond with delaying tactics and frivolous arguments.17

The umbrella companies mysteriously have enough money to run these delaying arguments (sometimes including expensive judicial reviews) but, once those arguments fail, usually run out of money, and become insolvent, never defending the scheme itself. In fact we’re unaware of a single case where one of these remuneration schemes has been defended before a tax tribunal.

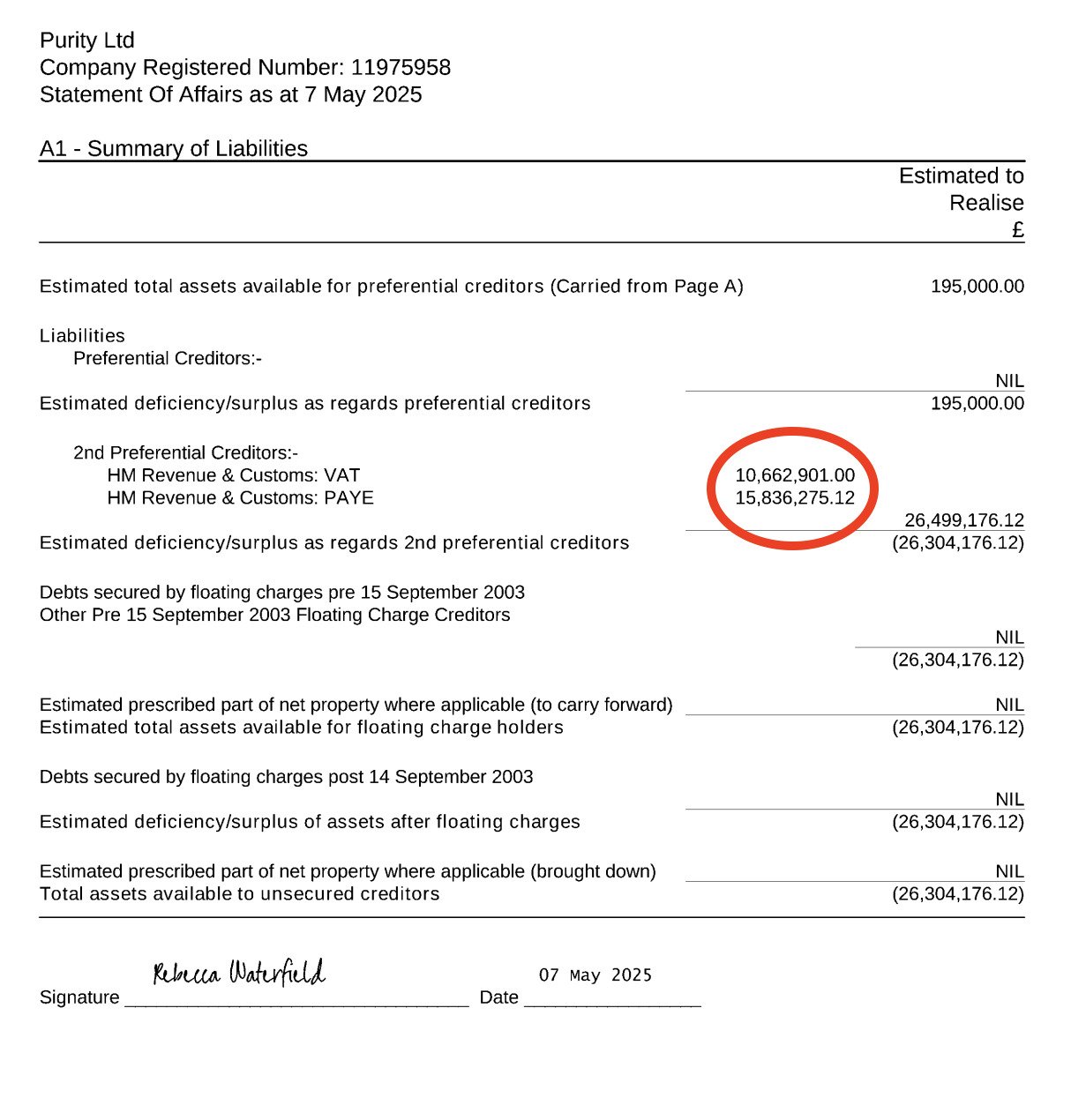

The point of the delaying tactics is to keep the money rolling in for as long as possible. Purity avoided tax on over £45m of remuneration, retaining a fee of £9m which it paid to its shareholders – but by the time it was put into liquidation, it had almost no cash – owing HMRC £26m:

In Purity, things were a little different. HMRC used a new power under section 85 of Finance Act 2022, which enables HMRC to present a winding up petition against the promoter of a tax avoidance scheme where a scheme doesn’t work and HMRC believe that it’s in the public interest for the promoter to be wound up. Purity is the first time that power has been used.

Purity played the usual game of delaying tactics. It commenced an appeal against HMRC’s assessment but then dropped it. It commenced a judicial review in 2024 to try to halt, or at least pause, HMRC’s section 85 proceeding. Judicial reviews are expensive undertakings; Purity seems to have had no problem funding multiple applications and appearances. However after the judicial review failed, Purity was left to go insolvent, and it ended up not defending the section 85 application. Another company running the same scheme, Alpha Republic, played the same game.

How much money is lost to these schemes?

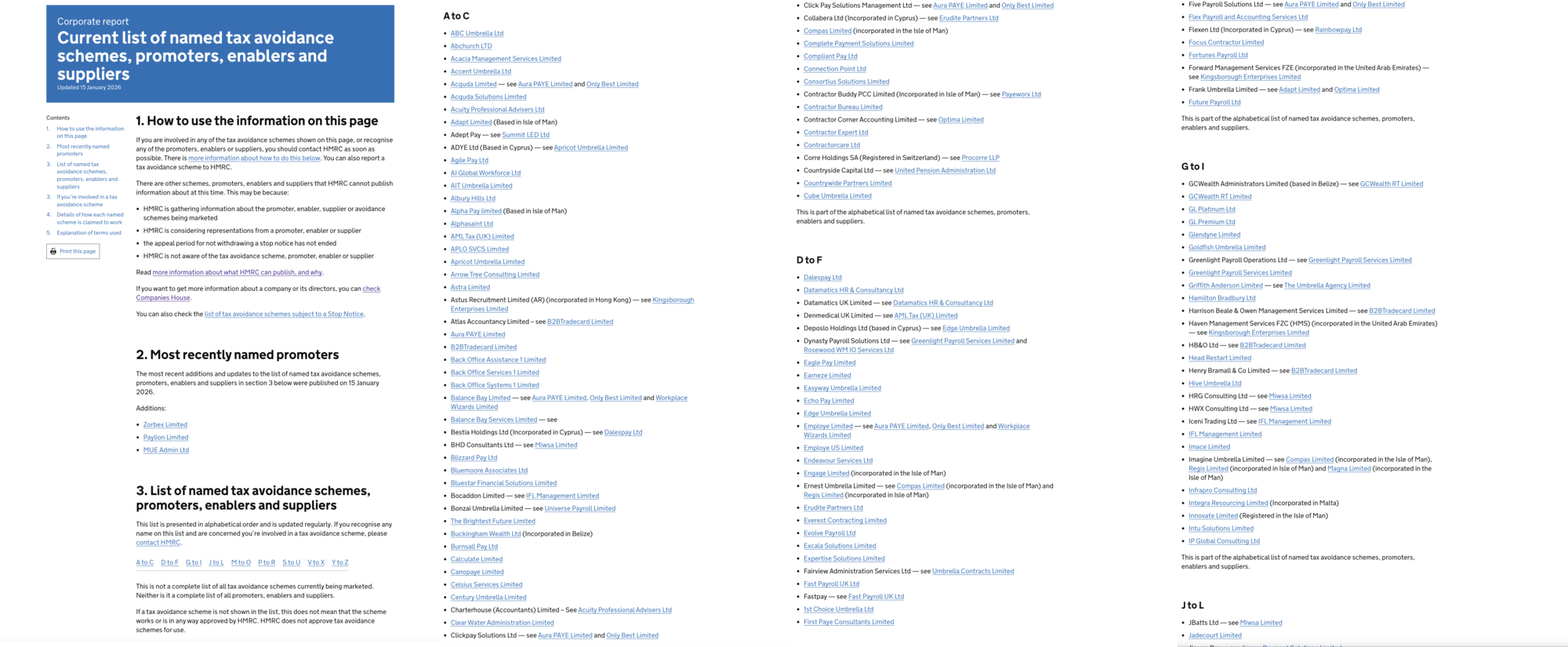

The Purity scheme and the related Alpha Republic scheme both cost £26m in lost tax. There are many such schemes. HMRC publish a list of named tax avoidance schemes and promoters, almost all of which are remuneration schemes like Purity:

This list currently has 165 entries (dating from 202218); around 50 are being added every year. If every scheme is responsible for a similar tax loss to Purity, that implies (very approximately) about £1bn every year – and these are just the schemes identified by HMRC.

The figure may be higher. We’ve spoken to informed sources within the “remuneration scheme” world who estimate several billion of tax is lost every year.

We’ve spoken to people at HMRC who believe these schemes could be one of the reasons for this:

Note how the large business and medium business tax gaps have fallen significantly over the last twenty years. The small business tax gap has risen, with a dramatic change from 2017/18 – representing billions of pounds of lost tax revenue. One plausible explanation for at least some of that increase is remuneration schemes (which are essentially being misclassified as small businesses). More on this here, with links to the underlying HMRC tax gap data.

Ending whack-a-mole

Currently HMRC is playing “whack-a-mole“. A promoter starts a scheme. Usually within a year, HMRC discovers the scheme and starts to issue a DOTAS number and/or a stop notice. The promoter employs the usual delaying tactics and, when these eventually fail, they wind up the company and move onto the next one. The individuals controlling these schemes are unknown to the public and often unknown to HMRC – they increasingly use stooges as directors to hide their identity.

None of this should be permitted. Aside from the lost tax, it’s harmful to the workers who get caught up in the scheme, and it wastes considerable HMRC and court/tribunal resources.

The Government published a series of proposals in the Autumn Budget aimed at promoters, with the intention of ending “whack-a-mole”. Most significantly, HMRC will be able to issue a “universal stop notice”, making promotion of particular schemes a criminal offence (currently stop notices have to be issued on a per-promoter basis). There will also be a general criminal offence of promoting tax avoidance schemes that have no realistic prospect of success.

However we fear that promoters will attempt to escape these rules by obtaining opinions from compliant KCs.19

The game will only truly end when barristers face professional and/or legal consequences for issuing knowingly or recklessly false opinions:

- The Bar Standards Board could make clear that it is a disciplinary matter for a barrister to provide an opinion which facilitates a tax scheme that has no realistic prospect of success. Specifically, where the barrister recklessly or knowingly makes key factual assumptions that he should have realised are probably untrue, or recklessly or knowingly adopts arguments that have no realistic foundation, it breaches a barrister’s core duty to act with honesty and integrity.

- In cases like Purity, HMRC could use its information powers to obtain copies of the KC advice, applying the iniquity exception from legal privilege.20 If the advice is improper, HMRC could pass it to the Bar Standards Board.21

- In suitably serious cases, HMRC could prefer the barrister for prosecution for tax evasion. Barristers have been prosecuted for tax evasion before – but, as far as we’re aware, that was always for their own taxes. We’re not aware of any case of a barrister being prosecuted for facilitating tax evasion by a client. The standard view is that an insuperable difficulty is that the KC’s advice is privileged. In cases like Purity, we believe prosecution should be considered. The scheme is either fraud or close to fraud – so there are grounds to believe that the iniquity exception from privilege applies.22

Jolyon Maugham wrote about this problem fourteen years ago. He’s not alone – many barristers, and many tax barristers23, are appalled by what their colleagues are up to. But nothing has changed. If the Bar Standards Board can’t or won’t act, Parliament should.

Thanks to the remuneration tax experts who provided their insights on the schemes, legislation and caselaw, particularly T, B and V. Many thanks to M for alerting us to the case, to K and B for advice on the FSMA aspects, and to P for their privilege expertise. Thanks most of all to our sources in the recruitment world.

Footnotes

By which we mean: there is a clear advantage in terms of circumventing/avoiding/evading tax and other legal obligations, but no clear bona fide reason for these structures. It’s not apparent why the law and public policy should permit these types of vehicles to exist. ↩︎

This figure isn’t in the judgment. We’ve estimated it as £45m of loans representing 80% of the remuneration of 90% of the workers implies £63m of total remuneration. If the workers were paid £50/hour then the number of workers = £63m / (£50/hour x 2,000 hours x 21/24 of a year) = 720 ↩︎

The judgment says the loans were interest-bearing – it’s not clear how this worked. ↩︎

This should probably be viewed as a drafting/structural error by Purity, albeit an extremely bad and obvious one. Perhaps it was required for marketing reasons as a way of reassuring employees who were nervous about the “loans”? ↩︎

That is why the “traditional” loan schemes involved a loan from a trust – the employees could be reassured that the trust had their interests at heart and wouldn’t in practice just demand repayment of the loans. These reassurances were in many cases false – the trust absolutely could demand repayment of the loans (and some have). But no legal reassurance at all can be offered when the employer is the lender. ↩︎

There is an excellent article on the GAAR here, from Tax Adviser magazine. HMRC have in practice been using the GAAR as a shortcut, to save all the time/cost of taking a case to trial. We’re only aware of one Tribunal case where HMRC actually pleaded the GAAR, but the Tribunal didn’t need to consider the point because the scheme failed conventionally. ↩︎

A hypothetical scenario in which we’d get to this point would be a realistic investment scheme structure, a series of artificial structural elements which take it out of the disguised remuneration rules, and a court/tribunal deciding that it can’t take a purposive approach to the rules. None of this is very plausible. ↩︎

We are approaching fantasy territory, but if none of the above rules applied and the GAAR didn’t apply then we’d expect retrospective legislation to be enacted. In 2004, the Government warned that future remuneration tax avoidance would result in retrospective legislation. Small-scale retrospective legislation duly followed in 2006, and much wider legislation (the “loan charge“) in 2019. ↩︎

HMRC appears to have made this point in passing. See paragraph 3 of the 2024 hearing. And note the stringency of the test – “wholly for the purposes of a business” where the loan is less than £25k (which monthly advances will have been), or “wholly or predominantly” in other cases. ↩︎

Note that, without this, it is possible that the loans would be regarded as remuneration for tax purposes but still as loans for general legal purposes – that’s an unjust result for the workers, but a consequence of courts being more reluctant to apply a “substance over form” approach to contract law than they are to tax law. The loan being unenforceable is a good result for the employees. It also adds an additional argument (not that it’s needed) for HMRC that the “loans” aren’t really loans at all. ↩︎

Note that it’s no defence to say that Purity retained discretion over whether any investment returns would in fact be applied to repay employees’ “loans”. The statutory test is not whether participants have a legally enforceable right to a distribution, but whether the purpose or effect of the arrangements is to enable persons “taking part” to participate in or receive profits or income arising from property. Here, the scheme was presented as a pooled investment intended (at least in principle) to generate returns which could be applied for the benefit of a defined class of UK workers, by meeting liabilities said to be owed by them. That is sufficient to bring the arrangements within the scope of s235, even if the operator retained discretion as to whether and when any payments were made. ↩︎

i.e. because if we assume Purity’s profit was around £12m, then even if Purity used all of it (!) to fund the investment scheme, and even if we ignore the employee’s interest payments, the investment scheme would need a 9% return for 15 years for the £12m to grow to £45m. ↩︎

There are perhaps two exceptions: the SHIPS 2 case, essentially because the legislation in question was such a mess that the Court of Appeal didn’t feel able to apply a purposive construction, and D’Arcy, where two anti-avoidance rules accidentally created a loophole. Both pre-date the GAAR. ↩︎

We are not saying that Mr Goodfellow is the KC who provided the opinion for the Purity structure (we’ve no reason to think he was – we don’t know currently who the Purity KC was). ↩︎

Another factor, particularly for the older KCs, is that their practice failed to adapt with the times. Back in the 1990s, many or even most of the top tax barristers and law firms had highly lucrative practices advising on tax avoidance schemes (although rarely called that; “structure finance” was a common term). A combination of new legislation and new judicial approaches meant that, in the early 2000s, it started to become clear that these schemes were becoming less and less likely to succeed. That pressure only increased over time – then the financial crisis, and the media and political focus on tax avoidance, ended the market almost completely. Most tax barristers (and solicitors) moved away from advising on these schemes (or, in some cases, retired) because the prospect of success were so poor, and well-advised clients wouldn’t go near them. For whatever reason, a small number of barristers did not, even though the legal prospects of the schemes were now extremely poor. These “old hands” have now been joined by a small number of younger barristers (generally their former pupils). ↩︎

Numbering fewer than a dozen, and all men. They are mostly KCs but some junior barristers are involved ↩︎

The claimed reasons for these schemes not disclosing under DOTAS are typically technically very weak, and/or based upon misrepresentations of fact. None of these arguments has ever prevailed before a tax tribunal. A short (and incomplete) list would be: Hyrax, EDF Tax, Opus Bestpay, White Collar Financial, PNO, Industria Umbrella, Smartpay, AML and Denmedical, IPS Progression, Greenwich Contracts, Saxonside, Dark Blue Umbrella. In some of those cases the promoter/taxpayer didn’t bother to turn up. In some (but not all) of the others, the barrister who represented the promoter/taxpayer is the same barrister who provided the false opinion backing the scheme. There are a handful of procedural taxpayer wins: Curzon Capital (the scheme was notifiable, but HMRC went against a mere administrator rather than the promoter) and Elite Management Consultancy (where HMRC missed a deadline). ↩︎

Before that date, HMRC was only permitted to publish names/schemes for twelve months. ↩︎

For example, the draft universal stop notice legislation has a “reasonable excuse” defence. Promoters will claim that they acted in accordance with a KC’s advice, and that was a reasonable excuse. The draft legislation attempts to prevent this by saying that the defence is not available if legal advice is unreasonable, or not based on a full and accurate description of the facts, but if advice is privileged then HMRC will have great difficulty applying this exception. ↩︎

The iniquity exception applies if documents come into existence as part of, or in furtherance of wrongdoing (including, but not limited to, crime and fraud). In our view, these schemes fall within the scope of the exception even if they do not amount to fraud, because the exception extends to underhand conduct which is contrary to public policy. (see the Al Sadeq case). If HMRC has difficulty establishing that the iniquity exception applies, then a specific statutory exclusion from privilege should be created for advice facilitating tax avoidance schemes which fail the GAAR “double reasonableness” test. ↩︎

That’s permitted by a specific exception to HMRC’s general duty of confidentiality. ↩︎

The iniquity exception applies if documents come into existence as part of, or in furtherance of wrongdoing (including, but not limited to, crime and fraud). The exception extends to underhand conduct which is contrary to public policy. In our view, these schemes fall within the scope of the exception (see the Al Sadeq case). ↩︎

Tax barristers have told us about instances where they’re approached for an opinion, particularly on DOTAS, and they say the opinion can’t be given. The client then goes elsewhere – and frequently to one of the KCs this article concerns. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Kerry Stephens Cancel reply