The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) has proposed large increases in gambling taxes to raise £3bn. The £3bn would be used to remove the two-child benefit limit and the household benefit, “lifting around half a million children out of poverty overnight”.

However there’s a gap between how the proposal is being pitched – taxing gambling companies on their large profits – and the reality. According to the IPPR itself it would be gamblers, not gambling companies, paying the price.

There’s also a gap in the IPPR’s calculations. This is a very large proposed tax increase – with the largest tax, remote gaming duty, rising 138%. But the IPPR’s calculation is “static” – it simply multiplies current gambling profits by the new rates. The IPPR justifies this with illustrative calculations showing gambling companies worsening their odds to maintain their profits. But there’s a point beyond which gambling companies can’t do that, and the IPPR’s proposal may go well past this point.

If the IPPR are wrong, and the tax can’t be passed on, then the revenues raised would be much less than £3bn – potentially half.

This is always the problem with “sin taxes”. We can use them to raise revenue. We can use them to deter the “sin”. But we need to be clear what we’re trying to achieve. And we need to be honest and admit that most of the tax is realistically paid by the sinners, not the companies selling the sin.

The proposal

The UK has a confusing array of different taxes on gambling. The IPPR paper proposes large increases in the most important ones:

- Remote gaming duty increased from 21% to 50%. This applies to online gaming supplied to UK customers, wherever in the world the supplier is, and is expected to raise about £1.1bn this year.

- Machine gaming duty increased from 20% to 50%. MGD applies to e.g. fruit machines, quiz machines, and fixed odd betting terminals. The tax raises about £600m this year.

- General betting duty increased from 15% to 25%. This applies to sports betting and most other gambling (except horse racing, which already pays an additional 10% levy). The tax raises around £700m.

The £2.4bn raised by these taxes would increase to about £5.6bn. This would probably be the rare case of a popular tax increase – Portland Communications found that, if they asked the public which taxes should be increased, gambling taxes topped the table.

In many cases we’d expect so large an increase in tax to reduce the gambling companies profits and, as these taxes apply to profits, result in only a small increase in revenue – or even a decrease in revenues (a “Laffer curve” effect). However, previous increases in gambling taxation have not had this effect: the rate of remote gaming duty went up by 40% from April 2019, and the result was a 33% increase in revenue.

That suggests there is potential to raise gambling taxes and raise revenue – but the IPPR’s increase is much larger – up to 138% for remote gaming duty. It therefore can’t just be assumed that history is a guide to what will happen. So it’s disappointing that the £3bn estimate is “static” – it doesn’t take account of “Laffer” effects. Instead, the IPPR justify the figure through an illustrative calculation.

The IPPR’s illustrative calculation, and what it means

The IPPR’s report says:

“It is only fair, therefore, that these companies, which are exempt from any form

of VAT and often based overseas, contribute more to help wider social aims

where they can – and the industry is booming.“

I think the reader would assume from this that it’s the gambling companies who end up paying the tax. That is, however, not necessarily the case. It’s usually thought that gambling companies respond to increases in gambling taxes by passing the cost on to gamblers, in the form of worse odds. Or, as an economist would say, the “legal incidence” of gambling taxes is on gambling companies – they pay the tax to HMRC, but the “economic incidence” of gambling taxes largely falls on gamblers.

The IPPR report relies on this, because it means profits aren’t hit, and so “Laffer” effects are limited:

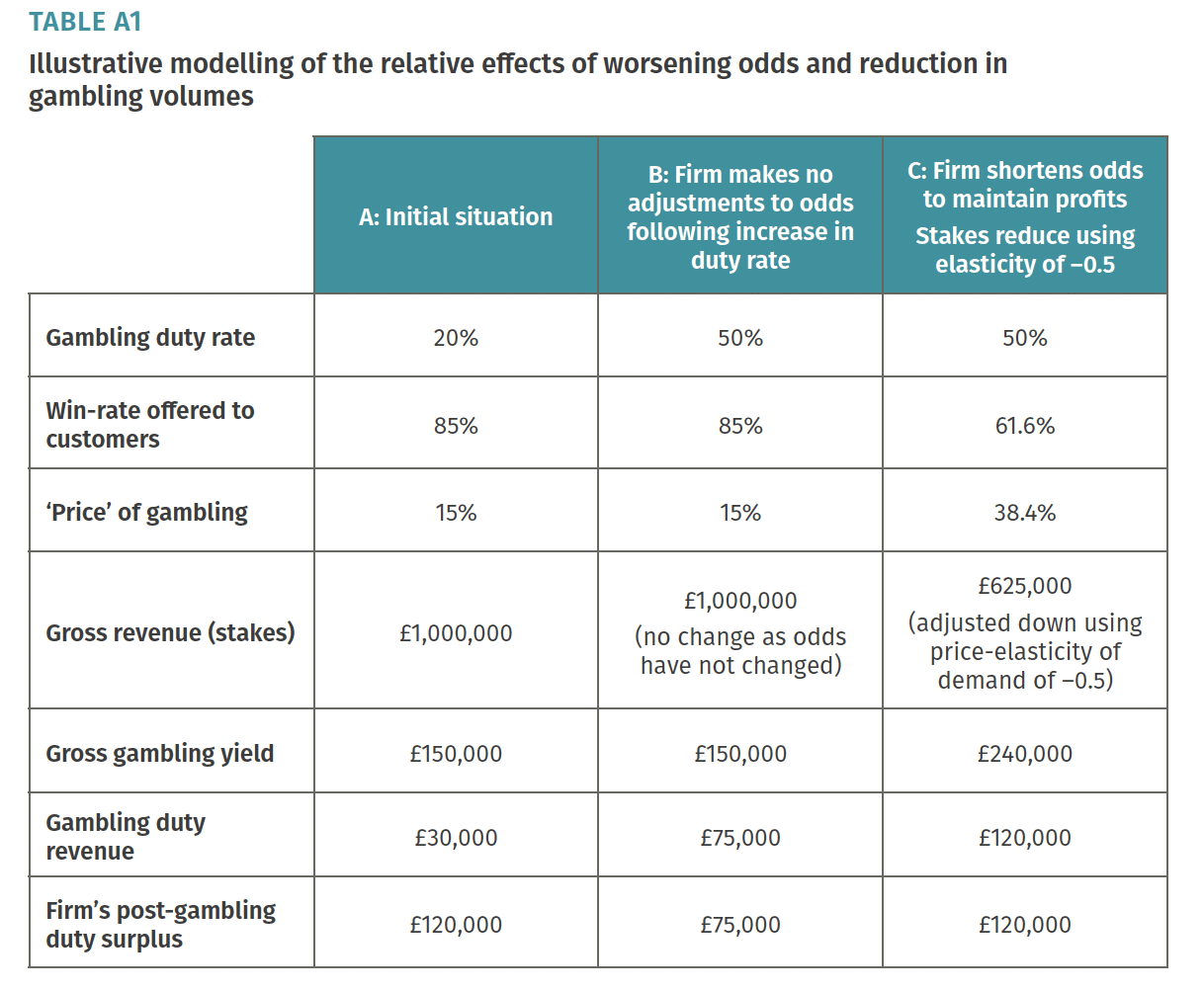

This approach is justified by an illustrative example which shows how the incidence falling on gamblers means that tax revenues increase, even when the rate rises significantly:

The first column is how things are now.

The second column is where the gambling company simply absorbs the increased gaming duty (with its post-tax profit dropping by about 40%).

The third column is what the IPPR thinks will happen: the gambling company protects its margin by worsening odds. Its revenue reduces by 40% but its profit remains the same. The increase in duty has, in economic terms, been entirely paid by gamblers.

This is a simplistic illustrative calculation. I doubt gambling companies would be able to pass all the cost of increased duties to gamblers (particularly for online gaming, where the odds across different platforms serving different countries are very visible).

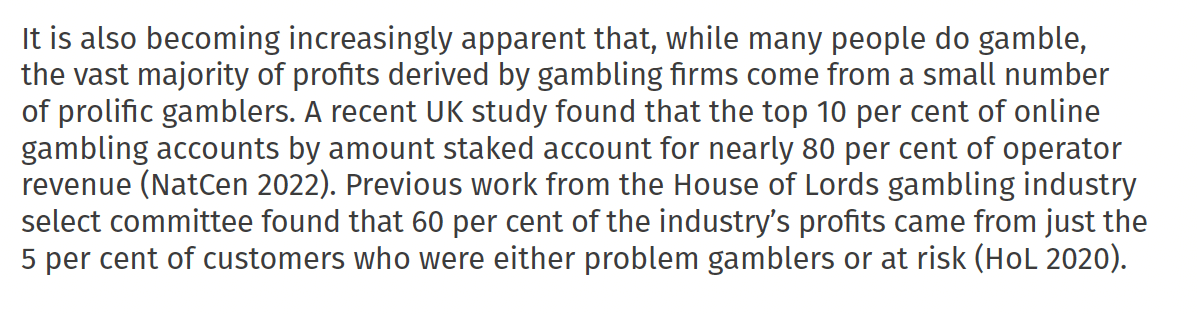

We should, however, expect a good part of the burden of the tax will economically be borne by gamblers. Whether that is an acceptable outcome is a political question. Personally I find it troubling because, as the IPPR report says:

And there is evidence from a Finnish study that the incidence of gambling tax may be particularly focussed on lower income gamblers.

What happens if the IPPR are wrong?

The figure in the IPPR’s illustrative table is based upon a “price elasticity of demand” of -0.5. In other words, that a 10% increase in the “price” of gambling (the odds) will result in a 5% decrease in the gambling revenue. This is a large effect, but IPPR’s illustrative figures show that gambling companies can (in principle) still protect their margins by worsening odds, and so making a greater percentage profit from that reduced revenue.

However there is a point where this stops working.

As the price elasticity rises beyond -0.5, gambling firms have to make the odds worse and worse to keep their margins. But there’s a limit – eventually the odds become impossible.

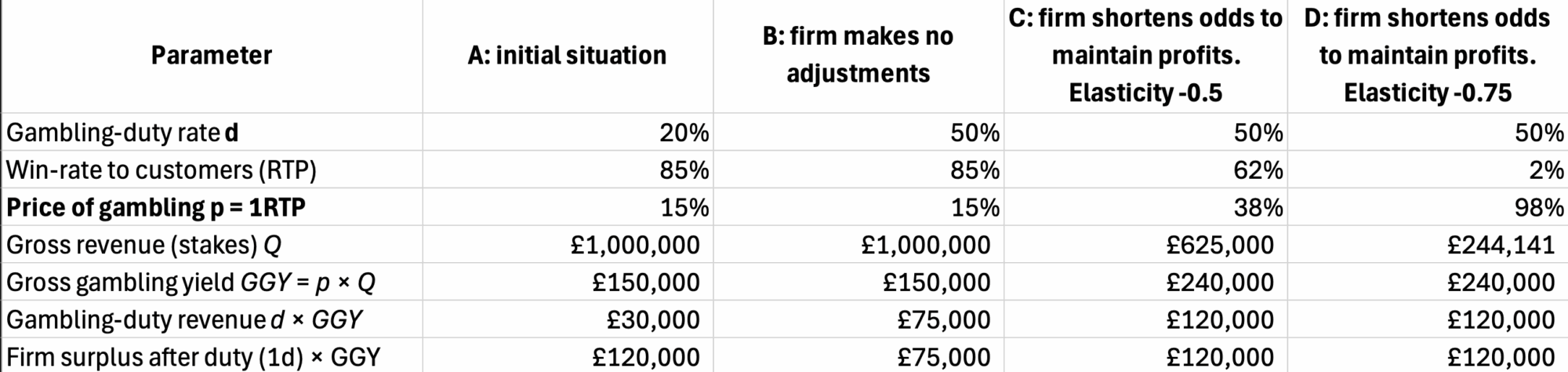

Here’s what happens if we add a column D to the IPPR’s table, with elasticity of -0.75:1The spreadsheet is available here.

At that point, margins can only be maintained if customers’ win-rate drops from 85% (as at present) to 2%. It’s unlikely anyone would gamble in such a scenario. And beyond -0.75, it becomes impossible to maintain margins with this strategy.

Gambling companies could, in principle, take the opposite approach, and maintain their margins by greatly increasing sales. It’s unclear if that’s possible, but I expect most people would consider it an undesirable outcome.

So the IPPR’s simple “illustrative” approach only makes sense if its estimate of a -0.5 elasticity is roughly correct. Beyond that point, their simple assumption that profits can remain broadly static fails, and a more complex analysis is required.

The calculation above is absolutely not a proper analysis – it merely identifies an important limitation of the IPPR’s illustrative calculation. There are numerous real-world factors which complicate matters,2The win rate/price of gambling is assumed; it of course varies for different forms of gambling. Firms could cut costs, alter marketing spend, shift product mix, or accept lower margins temporarily. For online gambling in particular, cross-border supply could constrain odds-worsening even before we hit the -0.75 threshold, because consumers could use VPNs etc to use foreign untaxed platforms. And, critically, elasticity is not constant – elasticities from smaller price changes don’t necessarily apply to very large price changes. and the real-world limit of the IPPR’s approach will not be -0.75 – a detailed analysis would be required to determine where it lies.

Is -0.5 the correct figure?

HMRC published a report by Frontier Economics in 2014 showing high elasticities, particularly for remote gaming duty: up to -1.8.

Earlier this year, the Social Market Foundation published a proposal to increase gambling taxes (more modestly than the IPPR’s proposal). The SMF were critical of the figures in the HMRC report, saying that much of it rests upon questionable assumptions rather than empirical evidence. The IPPR say they agree with the SMF.

The HMRC and SMF documents are both serious and considered pieces of work, and I and our team have not assessed the merits of the two positions.

But the point is of critical importance to the IPPR paper. if the HMRC/Frontier figures were correct then, applying the -1.8 (rather than -0.5) elasticity to IPPR’s numbers cuts the extra remote gaming duty revenue by about two-thirds. Because RGD is the single biggest component of the £3bn package, that alone would mean the whole yield would fall to about £1.5bn – half the expected £3bn.

Given the dependence on the -0.5 figure, it is therefore unfortunate that the IPPR present only one scenario. It would be preferable to admit the uncertainty and discuss the range of possible outcomes.

Conclusion

We need to be careful about trying to raise additional revenue from “sin” taxes. The revenue may be less than we expect, and what revenue we do receive may (in economic terms) come from customers rather than the businesses making the sale.

Personally I see compelling arguments for reducing the harms caused by gambling; but I’m unconvinced tax is a good tool for doing that. Regulation may be a better approach.

A tax increase may still be worth doing as a revenue-raiser. But any argument for an increase needs a more robust revenue estimate than the IPPR’s use of a static calculation and illustrative tables. And it needs to acknowledge who is actually paying the price.

- 1

- 2The win rate/price of gambling is assumed; it of course varies for different forms of gambling. Firms could cut costs, alter marketing spend, shift product mix, or accept lower margins temporarily. For online gambling in particular, cross-border supply could constrain odds-worsening even before we hit the -0.75 threshold, because consumers could use VPNs etc to use foreign untaxed platforms. And, critically, elasticity is not constant – elasticities from smaller price changes don’t necessarily apply to very large price changes.

Thanks to H for a discussion on elasticities and help with the modelling.

22 responses to “Why I’m torn on increasing gambling duties”

The tax increase will mean that in many small towns, there will be no bookies and therefore no tax income. Many shops are close to being unprofitable, Abingdon used to have five bookies, we are now down to two and soon to be one. Has the government calculated income tax loss.

Being in the slot machine business 40 years,you cannot lower the odds on slots as this will have a negative play feel factor punters will notice and after very short period will stop playing and find another form of gambling probably underground.

This proposed 50% MGD increase will no doubt have the laffer curve .

Alot of the stastics are wrong, these people need to work in the industry. They say tax will be passed onto the punter,not possible on modern slot machines win rate 92% for good feel factor and if was possible to reduce percentage punters will notice and turn their back on playing machines so result down turn in revenue.

This proposed 50% MGD will close lots of town centre amusement arcades, take for example arcade turns £6000 a week 50% MGD that leaves the business £3000 to pay rent rates wages electric, rent say £1000 + rates £500 + wages £1350 + electric £500 that totals £3350 running costs per week. This means closure for many Arcades.

My feeling is there are some real unintended consequences from doing this.

I am no lover of gambling and the real problems it can create.

1) I live in the city where the largest employer happens to be a certain online gambling company, and I can tell you they as well as employing a lot of people, they pay very well in an area considered to have a lot poor paying jobs. Therefore this could create more problems locally.

2) Raising the money and spending at they will claim, will not actually tackle problem gambling, which to the families it effects can be devastating. It may in fact worsen it.

3) Very naive this will life half million children out of poverty overnight, where is the evidence for this generalised statement, the fact is it won’t stop some parents from spending the extra cash on themselves and won’t help some children at all.

4) I would doubt this would raise the extra money year on year so what do you do then when it doesn’t!

The £3bn would be used to remove the two-child benefit limit and the household benefit, “lifting around half a million children out of poverty overnight”.

Would the tax be hypothecated for this or any purpose? Or will it disappear into general taxation for the government to use as it sees fit from time to time?

Thanks, as ever, for the article.

I can imagine the clientele breaks down into (at least) three distinct groups who may have significantly different elasticities of demand with respect to the odds they face.

As gambling firms try to pass on the taxes, my guess would be that

1) low propensity gamblers who are betting for fun may not care too much if the odds of winning become worse. They were paying for the ride rather than to get to the destination. elasticity = E1

2) wealthy addicts would be able to afford to continue to gamble and would pay the higher sin tax. elasticity = E2

3) poorer addicts would be less able to continue when faced with higher taxes. elasticity =E3

And I hypothesize, in absolute values, E1< E3 and E2 < E3.

If this hypothesis is correct, I think one could argue that the consequences of imposing/raising a sin tax are as intended.

Tax income not profit?

They do both – profit taxed at standard coroporate tax rates and income/revenue taxed at 21% (although this rate varies depending on product and channel). Addd in VAT/NI etc on purchases (remembering that VAT is not charged on thier sales and so they can’t recover vat paid) and you understand that gambling companies legitimately pay a % well north of 50% of revenue in taxes already.

I think we all realise that ultimately any tax or fine on a business is ultimately paid for by the customers of the business.

If it raises money for other things and helps deter gambling activity I’m all for it, though I am happy with the two child limit on benefits.

I would really like more restriction on gambling – particularly in terms of advertising and promotion to reduce people getting bad gambling habits

There’s another dimension to this, which is the potentially detrimental effect that the very large tax increases might have on the channelisation rate (i.e. how much of the gambling demand ends up in the legal/ regulated market). Anecdotal evidence suggests that this dynamic is at play in the Netherlands.

Admittedly, the industry very often cried wolf on this topic. Any regulatory change is usually met with this argument. But as the excellent industry analyst Alun Bowden indicates, the argument is probably more credible here than in other and previous instances.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/alun-bowden-6ab76a1b_a-position-paper-calling-for-a-50-tax-rate-activity-7359212053103796224-oV9t?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_android&rcm=ACoAAAb5AiIB5KjhL25xT0aLwqMEjyXEBGf5Fdw

There are serious concerns about the effects of gambling according to the commisssion.all companies will seek tominimis the effects of tax on their bottom line.an increase in taxes should happen.But i would also place an increased advetisingtaxattwolevels 1/ general 2/ a huge tax on any adverts which include free offers. Alternatively ban free offers

If betting were to decrease significantly as a result of the tax increase, would it not be reasonable to assume that the money saved by the punters would end up being spent in other ways, generating other economic activity of value (potentially taxable)?

potentially! Would love to see a full analysis of all these effects.

When I worked in the industry our credit betting operations depended almost entirely for any profit on one or two very large gamblers based overseas. This tax will only affect gamblers who have to place bets here in the UK. It’s clearly likely that taxing bets will encourage punters who can to go elsewhere in the world.

If the current administration is exploring the further possibilities of “sin taxes”, one which has not been proposed should be reconsidered.

The legalisation of cannabis and the potential tax revenues in that arena

I believe the USA has a much stricter regulation of the gambling industry, particularly offshore gambling . Isn’t this a method of ensuring they get a cut of the pie? I have always thought it supine of the UK government of every stripe not to take the attitude that if any internet company wishes to sell and access the British public that they need to pay a price irrespective of where they are based. Is it really beyond the wit of the government to come up with a suggestion and threshold as to how this ought to bite.

A reduction in odds would also result in pushing more price sensitive gamblers to consider their options with regards to the growing unregulated betting market. Bookmakers playing by the rules are likley to become more uncompetitive resulting in a reduction of Turnover for them and a higher risk environment for punters.

Being a former bookmaker, and whilst that was 25 years ago, I would love to understand the split in revenues from traditional sports i.e. Football, Greyhounds, Horses; so industries our betting public support and enjoy days out to with a side bet to enhance enjoyment.

Versus the very lucrative virtual gambling and casino, bingo, online side of the new betting spectrum, and of course least we forget the machines in betting offices.

There is a very large sporting industry in the UK that the betting levy supports this in itself is worth billions to the exchequer, and I would say besides the levy payment is by and large paid for by the very rich, so how much does employment raise, how much do match day and racing days pay in tax?

It is all to easy to say the Rich don’t pay taxes, but each large bloodstock yard, and racing yard, or team sponsorship is worth hundreds of millions per deal, how much of that is taxable… Billions and Billions.

Any insights on how a 40% decrease in gambling revenues would impact types of gambling (slots, horses etc) or gambler profiles, particulary ‘problem gamblers’?

Why not also tax winnings as well as the profits of the betting companies?

Amongst the problem with the Laffer Curve is it is a revenue maximisation curve not profit maximisation. Changes in behaviour by gambling firms are so difficult to predict particularly when governments don’t demand that they divulge. As a result, Laffer was wrong and it has been a major source of US fiscal deficits ever since. The sin tax is purely political. Revenue is never hypothecated. I hear the ranting Mr. “No More Boom and Bust” and his moral fervour. Giddy Osborne’s drivel when he introduced the two child limit to supposedly spend the saving on military veterans was no better.

This is not a viable conversation let alone policy. People will gamble just like they will have more than two kids whilst on precarious incomes or state transfers. The IPPR states that in the UK the model is held up by problem gamblers. That might be a place to start.

It’s just a source of revenue for them and I agree that they are likely to fall short. Just like Arthur Laffer. I’m not so much conflicted as certain that this is the wrong place to start.

Flutter Entertainment being an example, unintended consequences, Betting is an international business therefore the UK is one small piece of a cake and can be reduced very easily with higher taxes