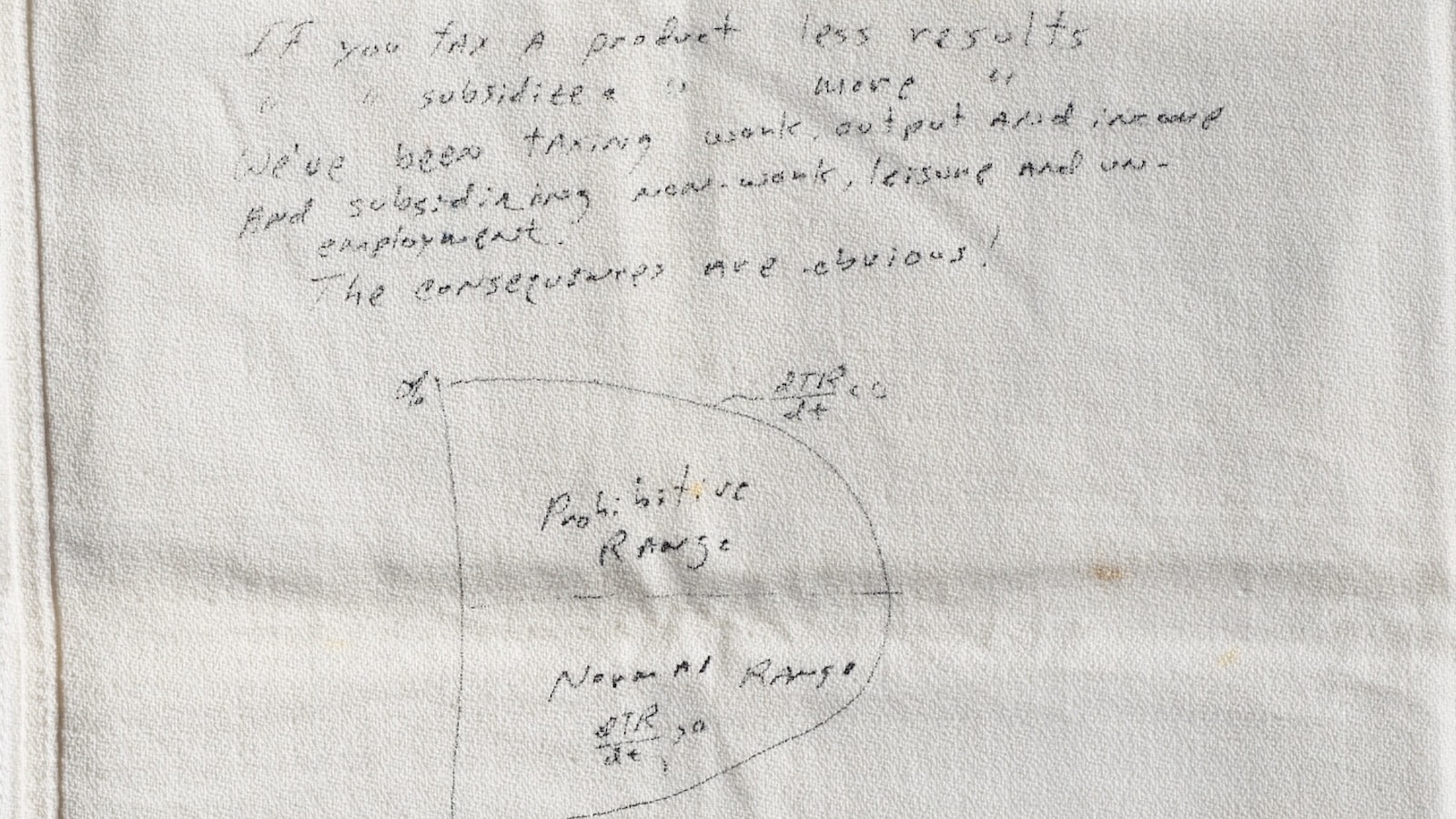

Art Laffer drew a curve on a napkin in 1974 that he said proved that tax cuts would pay for themselves. This is sometimes right, and sometimes wrong – and it’s a mistake to just assume the answer without looking at the evidence.

This article, written to accompany the first episode of Untaxing, looks at what the Laffer curve tells us about the Thatcher tax cuts of the early 80s, and the Scottish tax rises of recent years.

(This is an updated version of an article on the Thatcher tax cuts I wrote last year.)

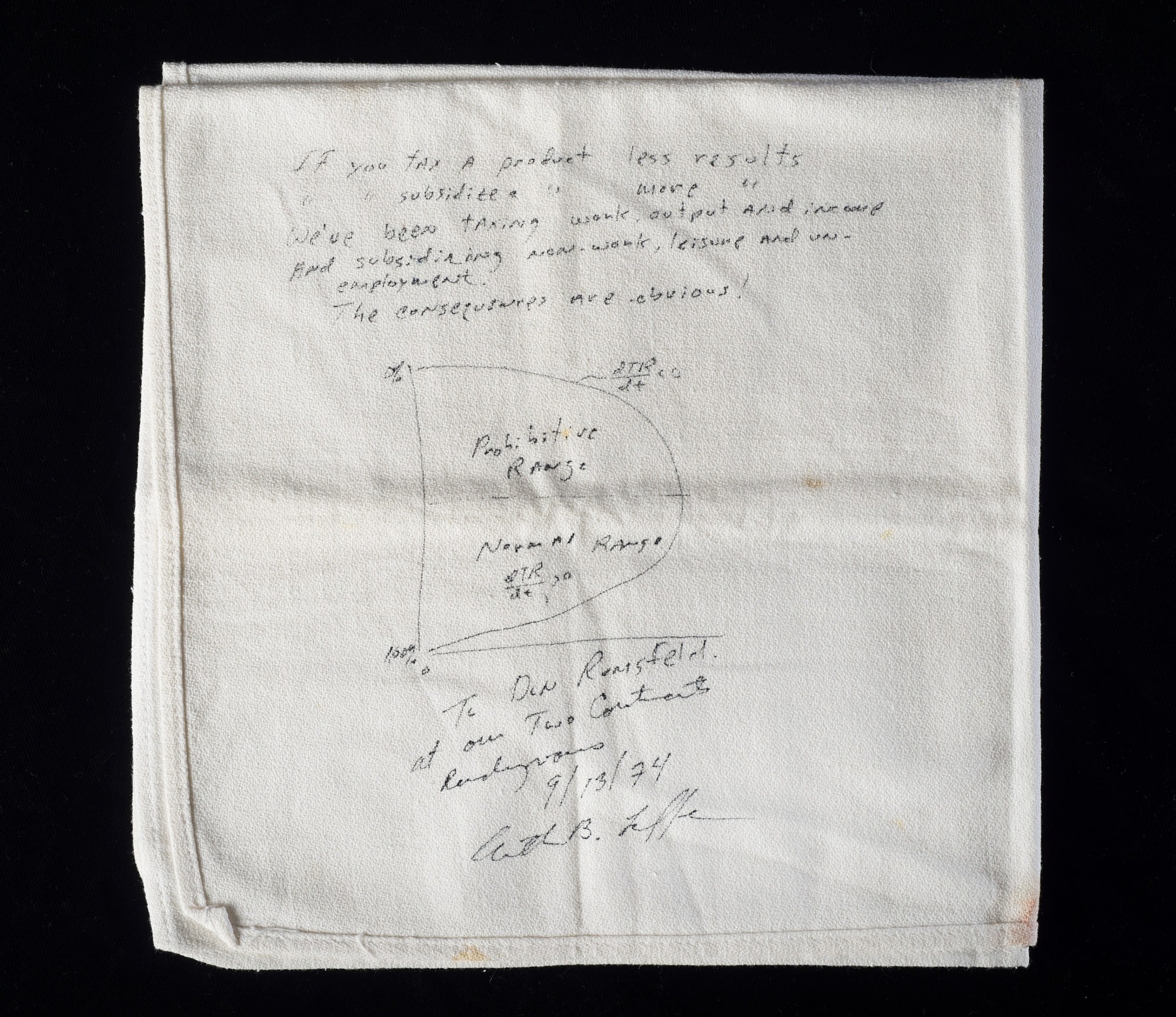

Art Laffer

In 1974, Art Laffer scribbled this curve on a napkin:

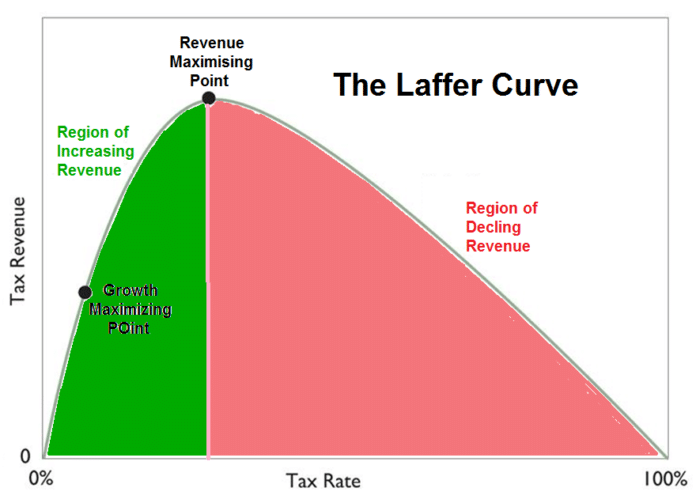

The concept is simple: at a tax rate of 0%, obviously no tax revenue is collected. At a tax rate of 100%, obviously nobody would perform any taxable work, and so no tax revenue is collected. Between these rates, some tax is collected. We can therefore draw a smooth curve. Logically, this will have a “maximum” – the tax rate at which the maximum revenue is collected. As you approach that point, you experience diminishing returns, with each % of tax increase collecting less and less revenue. Eventually, once you reach the peak, increasing rate rates actually loses revenue.

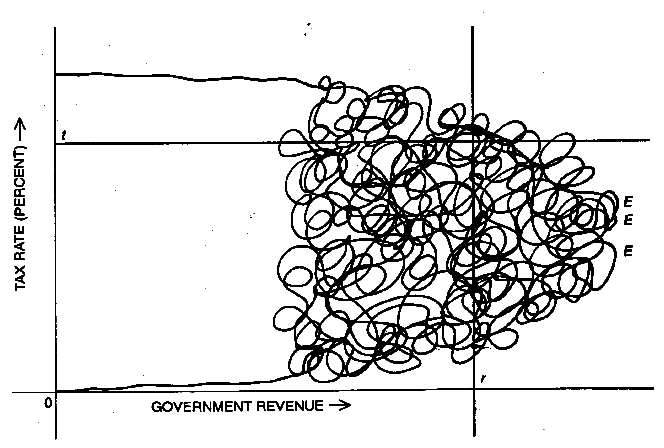

We can quibble with these assumptions.

A few people pay tax voluntarily (although not very many). Rather more people work for no pay – a good example is the voluntary sector, a less good example are the old communist economies. So the two ends of the curve will collect more than zero revenue.

It’s also very unlikely the curve would be this smooth – a variety of practical and psychological reasons, as well as fundamental mathematics, will make it more complex than that. Martin Gardner’s 1981 satire makes this point, but goes too far:

The basic point, however, is surely correct. There will be a “revenue maximising point”. As tax rates approach it, there will be diminishing returns. As tax rates pass it, revenues will fall.

The problem is that ascertaining that point is hard. It will vary from country to country, tax to tax, and will often change over time. It’s a mistake to assume (as Laffer himself seems to nowadays) that we are always approaching or beyond the peak of the curve, and so tax cuts will pay for themselves. But it’s also a mistake to take as an article of faith that tax cuts can never pay for themselves.

What does the evidence tell us?

When tax cuts probably paid for themselves

Margaret Thatcher and Geoffrey Howe cut tax dramatically in 1979.

aqw

In Howe’s first Budget, the rate was cut to 60%.

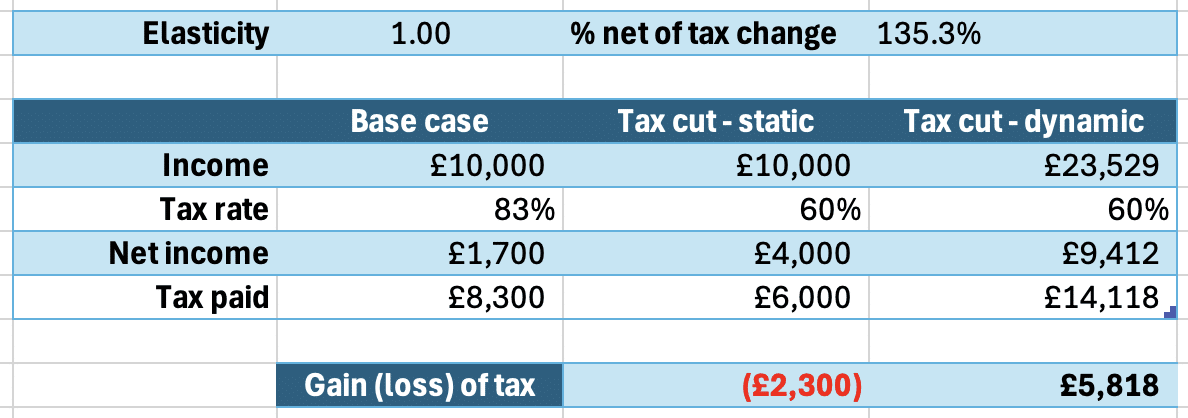

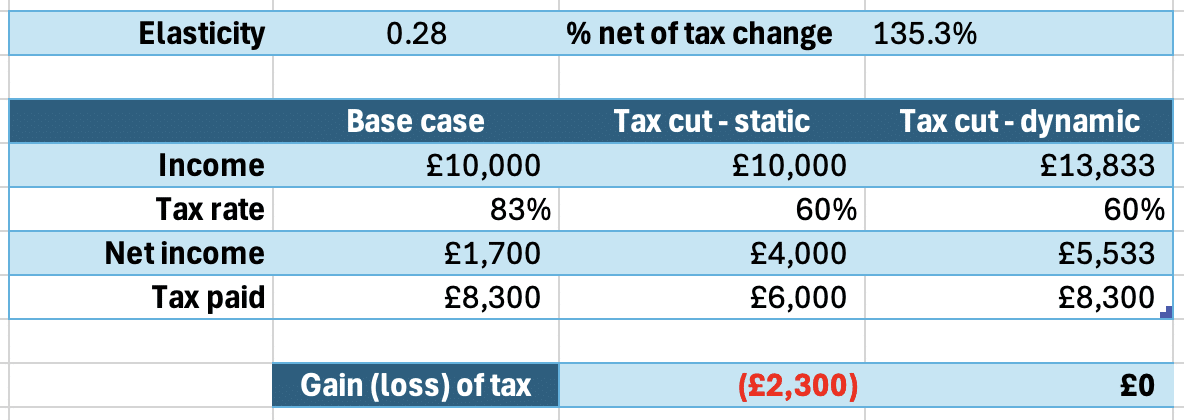

Wearing our 2024 spectacles, 83% to 60% isn’t a hugely generous tax cut. But think about what it means in cash terms. £10,000 taxed at 83% leaves you with £1,700. £10,000 taxed at 60% leaves you with £4,000. That’s a 135% increase in your after-tax income (“change in net of tax rate”, in the jargon).

This is a much more dramatic change than for the tax cuts we see discussed in 2024. There is literally no tax cut that could have this kind of impact today. Even cutting the top 45p tax rate all the way down to 1p would “only” increase after-tax income by 80%.

Intuitively, it feels plausible that more than doubling peoples’ after-tax income would have significant effects on peoples’ behaviour. But we can do better than “plausible” – let’s put some numbers on it.

A simple example

Economists talk about the “taxable income elasticity” – the TIE. That’s the degree to which people’s reported income increases as tax cuts leave them with more income after-tax. Why does it increase? Some mixture of incentive effects, reduced avoidance and reduced tax evasion.

Let’s say the TIE in 1979 for people paying the 83% rate was 1. This figure is almost certainly wrong, but it makes the maths easy, and we’ll come back to the true figure later.

And, whilst TIEs are usually applied to the aggregate tax base, i.e. the whole economy, let’s make our calculation simpler by assuming the economy consists of one taxpayer, who has £10k of earnings in the top tax band.1I’m ignoring another factor; Howe reduced the tax bands in real terms – that makes the tax cut even more effective than this simple model suggests.

Applying the hypothetical TIE of 1, then that Thatcher tax cut, with a 135% increase in after-tax income, would result in reported incomes increasing by 135%.

Instead of our one taxpayer earning £10k and paying £8,300 tax, they’d be earning £23,529. Perhaps they work more hours, perhaps they work harder, perhaps they stop avoiding tax or under-declaring income.2And in a real “whole economy” approach there would be other factors – increased net migration of high earners, deferred retirement, etc. And of course not all taxpayers paying the top rate of tax are the same – someone earning just a little more than £23,000 would have been very different from someone receiving millions. Either way, they are earning more, retaining more after-tax and paying more tax:

Everybody wins. It’s that rarest thing in economics – a free lunch.

You can download this example spreadsheet here. The “base case” is before the tax cut. The “static” column is with the tax cut, but ignoring elasticities. The “dynamic” column includes the TIE effect (but not other dynamic effects, e.g. economic growth – see below for that).

It’s important to stress that this calculation was purely illustrative – I pulled a taxable income elasticity of 1 out of the air, just because it made the calculation easier.

What would the TIE actually be?

A more realistic example

The problem is that estimating the TIE is hard. It varies between countries, changes over time, and is different for people earning different incomes, and even for people of different ages.3There’s a good discussion of these issues in this paper by Saez, Slemrod, and Giertz, see page 40.

There’s an even more important factor: the TIE varies depending on tax policy.4See the reference to “loopholes” on page 16 of Saez et al. Let’s say I can pay £50 for a tax avoidance scheme that magically reduces my tax rate from 83% to 60%. The TIE on the Howe tax cut would be enormously high, because all the people previously buying the scheme will now just declare their income.5This example is not that far away from some of the tax avoidance schemes that were common in the 1970s and early 1980s.

The TIE has to be inferred from natural experiments created by tax reforms and “kinks” in the tax system. For example, sometimes we see more taxpayers than expected “bunching” at a particular income point, just before a higher marginal rate kicks in (but estimating the TIE from these kind of effects is difficult).

A TIE of 1 is extremely high.6Note that I am talking here solely about tax on income – elasticities for some other taxes can be much higher. Stamp duty land tax is an extreme example, given that a person’s decision whether or not to buy a house will in some cases be entirely affected by SDLT. We tend to see elasticities like that only for people on very high incomes – think the top 1% – and in very exceptional circumstances.7There’s a good introductory Harvard lecture series on this – see here and here. It is possible that those circumstances applied to the UK 83% rate – I don’t know (and I’m not aware of any evidence on this).

We do, however, have some recent evidence from the UK’s more recent introduction and then repeal of the 50p top rate.8There is an outstanding House of Commons Library briefing paper on the history of the 50p top rate. HMRC used the resulting data to estimate a TIE of 0.48, but others have come to very different conclusions. 9One might think the UK’s brief 50% top rate was a beautiful natural experiment, but the brevity of the rate means that income effects are dominated by people accelerating their income to before the rate went up, and then deferring it until after the rate went down – the linked IFS paper goes into detail on the attempts to reverse-out these effects.

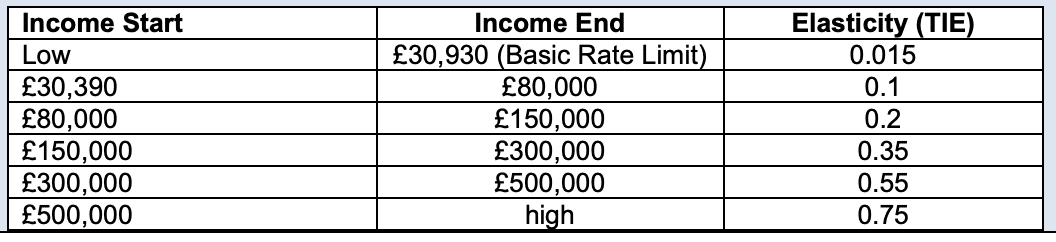

Here’s a table from the Scottish Fiscal Commission showing the TIE they expect at different income levels, based on the HMRC 50p data and a review of the literature:

So, given we can’t be sure what elasticity applied in 1979, let’s ask the question the other way round. What elasticity would be needed for the Thatcher tax cut to pay for itself, on our modelled £10k of income?10Obviously a different and much, much, easier question than “did the Thatcher tax cut pay for itself overall”.

A TIE of only 0.28.

I should stress again that modelling one taxpayer in this way is an extremely simplified approach, but that the numbers are so stark that we can still say it looks very plausible that the Thatcher top-rate tax cuts paid for themselves.

This was, however, an exceptional case for two reasons. First, the effect of the tax cut was very significant (with that dramatic 135% increase in after-tax income). Second, the tax rate, even after the cut, was very high – so a good chunk of the additional income that the tax cut incentivised into existence would itself be paid in tax.

When tax cuts won’t pay for themselves

What if the UK scraps its current 45p top rate?

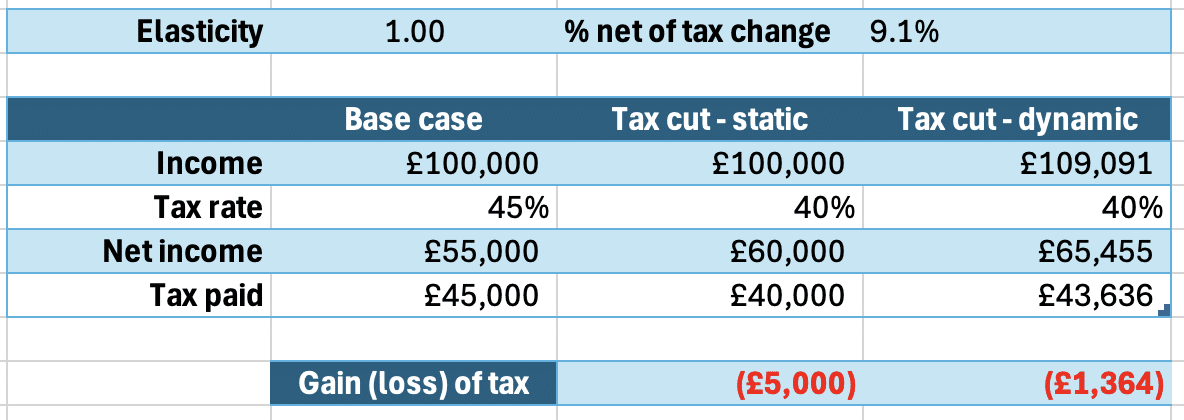

This would have a much less dramatic effect than Thatcher’s tax cut. A tax cut from 45p to 40p is the difference between retaining £55,000 and £60,000 from a £100k slice of gross income above £125k.11Important to remember that 45p is the marginal rate on this slice of income. The overall rate is much less – but it’s marginal rates that matter for incentives, and therefore for tax elasticity calculations. That’s not nothing, but it’s only a 9.1% increase in after-tax income.

We therefore need an exceptionally high elasticity for this tax cut to “pay for itself”. Even an (unrealistic) elasticity of 1 doesn’t cut it:12Although it comes quite close! See below re. Scotland.

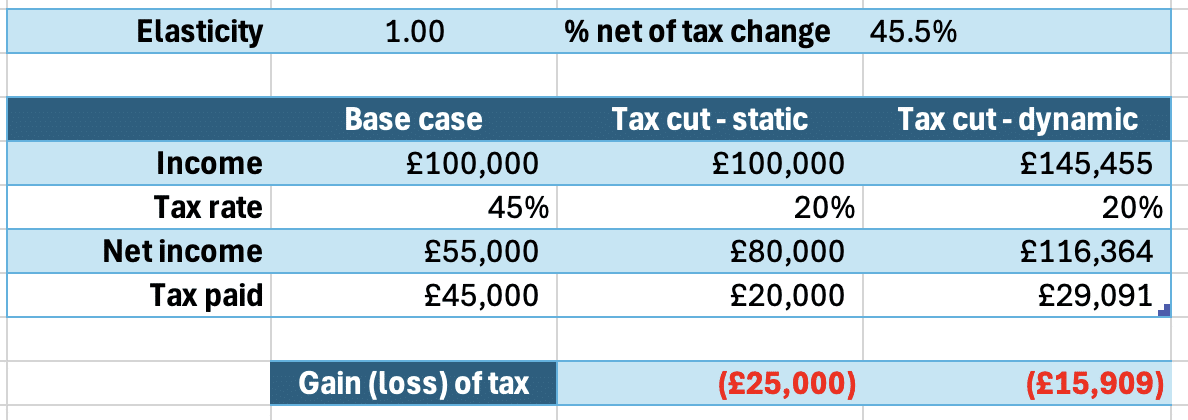

Let’s do something more exciting. What if we adopted a “flat tax”, with everyone paying a 20p rate? So the marginal rate on a £100k slice of gross income above £125k drops from 45p all the way to 20p.

Again, let’s assume an unrealistic elasticity of 1:

The flat tax isn’t even close to paying for itself. Why is that, given the sizeable 45% change in after tax income?

Partly because 45% is still a lot less than 135%. But also because that £45,000 of new income we’ve incentivised into existence is only taxed at 20%. It’s much, much harder for this tax cut to pay for itself than when the rate, even after the tax cut, was 60%.

I should repeat the caveat that it’s woefully simplistic to think of the economy as just one taxpayer but (as before) the numbers are clear enough to make the point.

So the depressing conclusion from this is that what was plausibly true in the 70s and early 80s probably isn’t true today – we shouldn’t expect income tax cuts to pay for themselves in the short/medium term.

There’s no free lunch in 2024.

Is the answer different in the long term?

Perhaps. Whether tax cuts pay for themselves in the long term is a different question, and one that’s highly contested.

Some economists believe the evidence shows that tax cuts in the US led to higher GDP and lower unemployment, with faster effects when the tax cuts benefit those on high incomes. Other economists have found no evidence that tax cuts for those on high income increases growth; conversely, others have found that tax cuts targeted at people on low income can increase growth.

There is also a view that funded and carefully implemented tax cuts may create growth, but unfunded/deficit-funded tax cuts will not.

I’m not an economist and so don’t have a position on these questions. However I would tentatively suggest that the lesson of the Truss/Kwarteng mini-Budget is that either the bond markets don’t believe unfunded tax cuts deliver growth, or they’re not patient enough to wait.13The outcome of the Truss/Kwarteng Budget tells us nothing about funded tax cuts, but it’s a rare politician these days who proposes to fund tax cuts with either other tax rises, or public spending cuts. Thatcher, by contrast, did fund her income tax cuts. Whilst the cut in the highest rate of income tax probably paid for itself, other income tax cuts (for example cutting the basic rate from 33% to 30%), did not – and they were much more expensive. So Howe’s Budget raised the rate of VAT from 8% to 15%; later tax cuts were partly funded by revenues from oil and gas taxation.

What does the TIE tell us about raising taxes?

The simple spreadsheets above show the position for hypothetical individual taxpayers. They don’t attempt to model the impact across all taxpayers.

You can, however, use the TIE in a more sophisticated calculation to find the “revenue maximising tax rate” – the top income tax rate that will raise the highest amount of tax, based upon assumptions as to the shape of the income distribution.14If we assume income is flat, the revenue-maximising rate is simply 1 / (1 + TIE), but we shouldn’t assume income is flat.

So, let’s forget tax cuts for the moment, and answer a different question: can we raise more revenue by increasing tax on those on the highest incomes?

One influential paper estimated that, if the TIE is 0.46, then the revenue-maximising tax rate on the highest earners would be 56.5% (see page 102).

An employed15Employer’s national insurance means the marginal rate is much higher for an employee than someone who is genuinely self-employed, or an investor. high earner in England today pays a top income tax rate of 45%, plus 2% employee national insurance – and their gross wages are subject to 15% employer national insurance.16That’s relevant because, in the long term, the burden of employer national insurance falls on employees. That’s a total effective rate of 55% – rather close to the revenue-maximising rate.17One might think the current effective rate is 62% (45% + 2% + 15%) but the employer NI is a % of the gross salary, and income tax and employee NI is a % of the same gross salary number. As an example: imagine a highly paid employee receiving a £100 pay rise. Employer national insurance applies at 15%. There is then 45% income tax and 2% employee national insurance – so employee taxes of £47. So the total tax is £62 (£47 plus £15) out of a total of £115 paid by the employer – a rate of 53.9%. (Apologies for the error in the original version of this article, which said the rate was 54.95%). More if we take indirect tax into account.18Whether we should do that, and how we should do that, isn’t clear to me. Brewer et al uses a 52.7% figure (on page 91) that includes indirect tax, but doesn’t explain where it comes from.

There are a large number of uncertainties – the TIE itself, as well as the assumed shape of the income distribution. So the 56.5% figure should not be taken as a policy absolute – but it does suggest that we should be cautious about assuming that increasing the 45p rate will raise more tax.

The Scottish experiment

The Scottish government is kindly conducting a controlled trial into what happens if you do go higher than 45p.

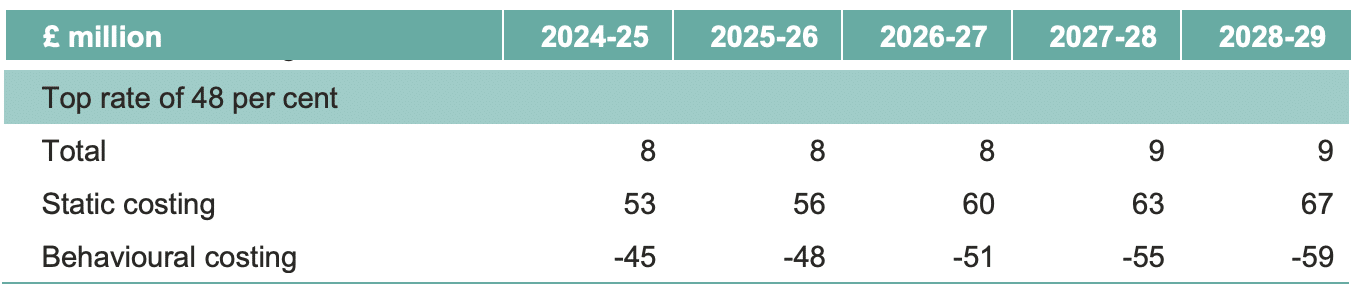

In last year’s Scottish Budget, the top rate went up to 48p (from 47p). Here’s the Scottish Fiscal Commission’s figures on how much that will raise:19See figure 4.12

Almost all (85%) of the potential revenue from the 48p rate vanishes in “behavioural responses”. The £53m of theoretical revenue turns into a mere £8m.

This is an extremely inefficient tax increase.

These figures are estimates, not measurements. They are based on the best available research on taxable income elasticities, but the margin of error is wide. The tax increase could raise more than expected. Or, given how close the net revenue is to the break-even point, it wouldn’t take much for the behavioural response to exceed the static revenue. In other words, for the tax increase to lose money.

This is why the IFS says that the Scottish top rate of tax may reduce revenue.

There are two additional complications.

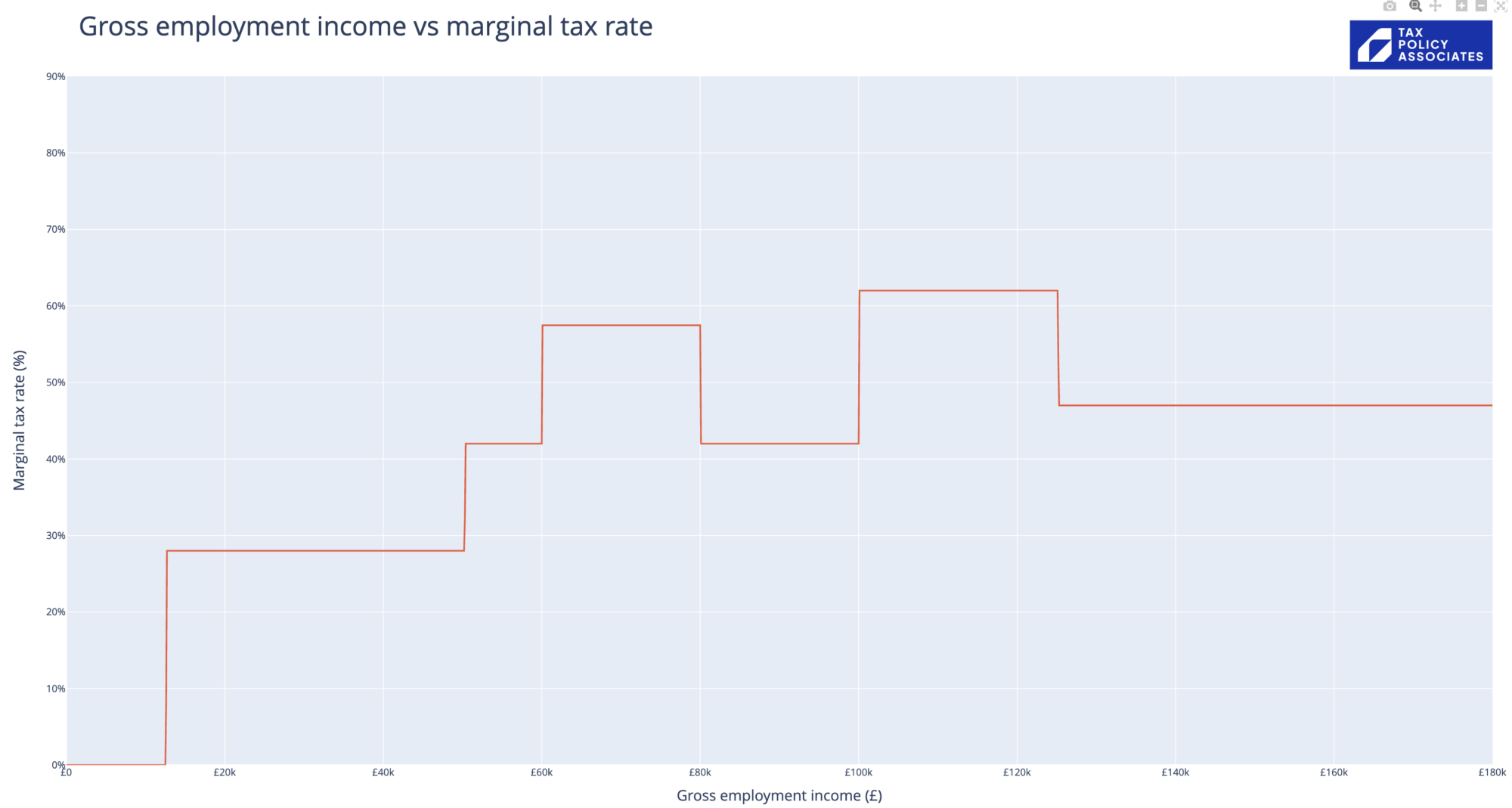

First, the actual marginal rates are higher than the headline (“statutory”) rates because of the silly gimmicks introduced by UK politicians to extract tax without raising rates: principally the clawback of child benefit between £60-80k and the tapering of the personal allowance between £100k and £125k. In most of the UK, that creates marginal rates like this, assuming a taxpayer with three children:

For Scotland, it’s significantly higher, with the personal allowance clawback taking the marginal rate to almost 70%.

There is also another anomalously high 50% marginal rate between £43.7k and £50k because Scottish 42% higher rate (42%) kicks in whilst an employee is still paying national insurance at the full primary rate (currently 8%).20Thanks to Rebecca Benneyworth in the comments for making this point.

All these effects combine to create a marginal rate that looks like this (again assuming a taxpayer with three children):

These high marginal rates may be a bigger issue in practice than the 48% top statutory rate (but I sadly didn’t have time to go into marginal raters on Untaxing). You can view our interactive marginal rate chart here.

The second complication is that we may well find that elasticities that are reasonable for the UK as a whole are not appropriate for Scotland. Scottish taxpayers have a magical tax planning solution available to them that UK taxpayers don’t. They can leave Scotland, or not return, or not arrive in the first place. 21These effects will be small, but they are real, and across an economy small effects can matter. And migration is a particularly bad effect for a tax rise to have, because you’re not just losing some marginal amount of a taxpayer’s income – you’re losing all of it. A more subtle effect: there will be people who spend a roughly equal amount of time in Scotland and time in England/Wales/Northern Ireland. They could make very minor changes to their life and switch residence – or indeed slightly stretch the truth without anyone noticing.22Strictly that is tax evasion, but the kind that is very hard for anyone to detect. This is a controversial point because it implies that any future independent Scotland would have a practical limit to its ability to diverge its tax policy from the rest of the UK – nevertheless, the logic seems to me to be hard to resist.

We should know the result of the Scottish experiment in a few years’ time.

I should add some disclosure: I’m a member of the Scottish Government’s Tax Advisory Group, but we were not involved in the decision to raise the top rate. It was entirely political.

Is it just about the numbers?

Of course some people believe high taxes on those on high incomes are justified for reasons other than tax revenue – for example to reduce inequality by reducing the after-tax incomes of people on high incomes.23There is also a deeply counter-intuitive view that higher taxes can encourage entrepreneurship. Others believe that we shouldn’t be trying to maximise tax revenues, but rather maximise economic growth24i.e. because when we are the Scottish point of (probably) increasing tax revenue but extremely diminishing returns, some of the tax revenues “lost” to behavioural effects represent real lost economic growth or welfare. Some believe that high taxes are not very effective at reducing inequality. And of course some believe that high taxes are immoral per se.

My take is that, if you want to raise more tax from people on high incomes, you should not do so by raising the top rate of income tax, but focus on the base – for example capital gains tax. And if we want tax cuts, then at the present levels of income tax, we have to fund them.

Laffer Curve napkin image is the property of the Smithsonian and used here under their terms and for educational/non-commercial use consistent with the principles of fair use under Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act.

- 1I’m ignoring another factor; Howe reduced the tax bands in real terms – that makes the tax cut even more effective than this simple model suggests.

- 2And in a real “whole economy” approach there would be other factors – increased net migration of high earners, deferred retirement, etc. And of course not all taxpayers paying the top rate of tax are the same – someone earning just a little more than £23,000 would have been very different from someone receiving millions.

- 3There’s a good discussion of these issues in this paper by Saez, Slemrod, and Giertz, see page 40.

- 4See the reference to “loopholes” on page 16 of Saez et al.

- 5This example is not that far away from some of the tax avoidance schemes that were common in the 1970s and early 1980s.

- 6Note that I am talking here solely about tax on income – elasticities for some other taxes can be much higher. Stamp duty land tax is an extreme example, given that a person’s decision whether or not to buy a house will in some cases be entirely affected by SDLT.

- 7

- 8There is an outstanding House of Commons Library briefing paper on the history of the 50p top rate.

- 9One might think the UK’s brief 50% top rate was a beautiful natural experiment, but the brevity of the rate means that income effects are dominated by people accelerating their income to before the rate went up, and then deferring it until after the rate went down – the linked IFS paper goes into detail on the attempts to reverse-out these effects.

- 10Obviously a different and much, much, easier question than “did the Thatcher tax cut pay for itself overall”.

- 11Important to remember that 45p is the marginal rate on this slice of income. The overall rate is much less – but it’s marginal rates that matter for incentives, and therefore for tax elasticity calculations.

- 12Although it comes quite close! See below re. Scotland.

- 13The outcome of the Truss/Kwarteng Budget tells us nothing about funded tax cuts, but it’s a rare politician these days who proposes to fund tax cuts with either other tax rises, or public spending cuts. Thatcher, by contrast, did fund her income tax cuts. Whilst the cut in the highest rate of income tax probably paid for itself, other income tax cuts (for example cutting the basic rate from 33% to 30%), did not – and they were much more expensive. So Howe’s Budget raised the rate of VAT from 8% to 15%; later tax cuts were partly funded by revenues from oil and gas taxation.

- 14If we assume income is flat, the revenue-maximising rate is simply 1 / (1 + TIE), but we shouldn’t assume income is flat.

- 15Employer’s national insurance means the marginal rate is much higher for an employee than someone who is genuinely self-employed, or an investor.

- 16That’s relevant because, in the long term, the burden of employer national insurance falls on employees.

- 17One might think the current effective rate is 62% (45% + 2% + 15%) but the employer NI is a % of the gross salary, and income tax and employee NI is a % of the same gross salary number. As an example: imagine a highly paid employee receiving a £100 pay rise. Employer national insurance applies at 15%. There is then 45% income tax and 2% employee national insurance – so employee taxes of £47. So the total tax is £62 (£47 plus £15) out of a total of £115 paid by the employer – a rate of 53.9%. (Apologies for the error in the original version of this article, which said the rate was 54.95%).

- 18Whether we should do that, and how we should do that, isn’t clear to me. Brewer et al uses a 52.7% figure (on page 91) that includes indirect tax, but doesn’t explain where it comes from.

- 19See figure 4.12

- 20Thanks to Rebecca Benneyworth in the comments for making this point.

- 21These effects will be small, but they are real, and across an economy small effects can matter. And migration is a particularly bad effect for a tax rise to have, because you’re not just losing some marginal amount of a taxpayer’s income – you’re losing all of it.

- 22Strictly that is tax evasion, but the kind that is very hard for anyone to detect.

- 23There is also a deeply counter-intuitive view that higher taxes can encourage entrepreneurship.

- 24i.e. because when we are the Scottish point of (probably) increasing tax revenue but extremely diminishing returns, some of the tax revenues “lost” to behavioural effects represent real lost economic growth

4 responses to “Untaxing – The Laffer curve, and the napkin that changed the world”

I was on a plane in 1979 when the captaain announced the reduction in the top rate from 83% to 60%. A huge cheer went up!

I was on that rate, althoughy not a top earner, just a senior manager. Much of our management team’s time was spent on finding ways to get round it.

I have long been fascinated by the Laffer Curve and even at 92 interested enough to read Jon Moynihan’s convincing argument in “Return to Growth”.

Excellent analysis for a very tricky subject.

Looking at Scottish income tax, I’m very interested in the impact of the Scottish higher rate (42%) coming in at £43,662 when an employee is still paying NIC at the full primary rate (currently 8%). This gives a marginal rate of 50% on income up to £50,270 when the NIC drops to 2%. I would suspect that middle managers (assumed to be in this income range) working in the Borders would be very likely to live south of the Scottish border; it seems to undermine productivity in a key group of workers, who might alternatively reduce their hours to a 4 day week to avoid this rate. I do wonder whether the Scottish Government has modelled this.

I agree; the interaction between the Scottish rates and the NIC boundaries is something that doesn’t seem to have been properly considered.