Paul Baxendale-Walker is probably the UK’s most notorious tax avoidance scheme promoter. He’s the former barrister and solicitor who helped create the “loan schemes” that cost the country £billions and have caused misery for tens of thousands of people. HMRC say his schemes avoided £1bn in tax. His advice was negligent, and he eventually ended up struck off, bankrupt, and convicted of forgery.

HMRC have been trying to pursue Baxendale-Walker for years, and finally last year imposed a £14m penalty on him. But HMRC made a series of mistakes, including missing a statutory deadline. The consequence, confirmed by a court judgment published earlier this month, is that Baxendale-Walker escapes the £14m penalty.

This appears to be part of a pattern of HMRC failing to properly use the many additional powers it’s been granted over the last few years.

Paul Baxendale-Walker is notorious amongst tax advisers, but is very little known outside that circle. To understand the seriousness of HMRC’s failure to make the £14m penalty stick, it’s necessary to go through some of his career.

Table of Contents

- Baxendale-Walker – a short history

- The HMRC investigation

- The £14m penalty

- What went wrong

- Why did HMRC fail?

- Baxendale-Walker’s response

- The wider failure to stop promoters

Baxendale-Walker – a short history

We’ve previously written about the trust and loan schemes used in the 2010s to avoid very large amounts of tax, and that culminated in financial and personal disaster for many of those involved, and bankruptcy for the Rangers Football Club, which had used a particularly aggressive variant.

The adviser to Rangers, and one of the originators of the entire loan scheme structure, was former barrister and (now) struck-off solicitor Paul Baxendale-Walker.1Baxendale-Walker denied this to us, and claims his advice was not followed. He told Channel 4 News that he hadn’t advised Rangers at all; “somebody” had advised Rangers, using his book. But the Supreme Court itself said that Baxendale-Walker devised and operated the Rangers scheme.

The avoidance schemes

Baxendale-Walker emerged as a prominent adviser in the 1990s, co-writing what was seen as the leading textbook on “remuneration trusts”. These were the vehicles used for the trust and loan avoidance schemes. The basic idea was that, instead of an employer paying its employees in normal taxable wages, it would make payments to the trust. The trust would then loan the amounts to the employees. The loans wouldn’t be taxable, and the employees would often be told (with a nod and a wink) that they’d never have to be repaid.2The fact that the loans would never be repaid is often denied by scheme promoters, and PBW has denied it to us. But it is in fact inevitable. The loans were clearly a substitute for employee wages – instead of receiving £100,000 of taxed income, the employee would receive a £100,000 supposedly untaxed loan. Great. But if the employee repays the loan, they have nothing. The trust that received the loan repayment would typically be prohibited from returning any money to the employee. This was never an outcome that people would want or accept. We have reviewed dozens of loan schemes and hundreds of loans, and spoken to hundreds of scheme users – none ever saw a loan repaid, and (before the schemes collapsed) none thought that was a realistic outcome. So, as if by magic, taxable income had been converted into completely non-taxable income.

Baxendale-Walker sold variants of his trust structure to multiple clients through his firm, Baxendale-Walker LLP and related entities. He became a very wealthy man, started to moonlight as a porn star and talkshow host and acquired “Loaded” magazine (reportedly describing himself as a “porn baron”) through a publishing venture which went bust a year later.3PBW has denied to us that he owned Loaded – he says he never owned Loaded Media Limited or Blue Publishing Limited. But Companies House filings show him as the sole shareholder of both companies, and of the related production company Bluebird Productions Limited. PBW’s acquisition of Loaded and his involvement with Bluebird Productions Limited was widely reported at the time in the legal and general press. When we put this to PBW, he says he was merely a nominee. PBW was registered as the person with significant control of Bluebird Productions Limited up until the point it dissolved in 2019 (which suggests he was not a nominee). Blue Publishing Limited remains in existence, with PBW the sole director and company secretary; no PSC has been registered, which appears to be a breach of company law by PBW (whether or not he was a nominee). Loaded Media Limited was dissolved in December 2016; a PSC should have been registered from April 2016 but there again appears to have been a breach of company law by PBW.

Baxendale-Walker charged enormous sums for his tax schemes – 10% of the value of the trust in one case (£612,000) and 10% of all ongoing contributions in another.4Lawyers and other tax advisers usually charge by the hour, or sometimes with a fixed fee. Tax avoidance scheme promoters often charge by reference to the value of the tax benefit (explicitly or implicitly). A fee equal to 10% of the value of the property – not the benefit, but the property – is astonishingly high. In our view, none of these schemes worked technically.5Even before more aggressive anti-avoidance rules were introduced in 2010, we believe the loan schemes all failed. In some cases they were shams. Even when they weren’t, there were two very serious problems with the structure. First, the “loans” were not really loans, as there was no intention to repay them. HMRC and the courts sadly took a long time to understand this. Second, most of the loan scheme trusts excluded all the intended beneficiaries (to avoid a tax charge) but the trustees nevertheless made interest free “loans” to these people, despite the fact that this was clearly a benefit. Their argument was that an interest free loan was not a benefit – we would say that is plainly incorrect, and we therefore agree with those who say the trustees must have acted in breach of trust. Anyone who disagrees is welcome to make a large interest free loan with no repayment date to Tax Policy Associates Ltd. Some of his clients deserved their schemes to fail; others appear victims of mis-selling6We have heard from several sources that PBW never put any of his advice in writing, relying on his ability to “persuade” clients that the attractiveness of his loan trust suggestion spoke for itself. Most of the tax avoidance scheme promoters we’ve written about took a similar approach.7The avoidance schemes weren’t limited to tax; Baxendale-Walker was also involved in a scheme that purported to enable people to access their pensions before retirement (a so-called “pension liberation scheme“). The Pension Regulator’s position was that the scheme constituted misuse or misappropriation of the pension assets, and in 2014 they applied for an injunction against him and others involved. Baxendale-Walker appeared at the court hearing on the first day representing himself. He announced that there were “many more remunerative things” he could do with his time than attend the court, and declined to attend subsequent days. This worked about as well as one would expect, with the court ruling that Baxendale-Walker’s interpretations of the law were incorrect; he and the other defendants then agreed to discontinue the schemes.

The downfall

Baxendale-Walker was suspended from practice as a solicitor in 2005 for a “remarkable and colossal” and “breathtaking” error of judgment in saying that a Mr Nurkiman, who he had never met or spoken to was a “person of integrity and good standing”. Mr Nurkiman turned out not to exist, and the arrangement was fraudulent.8PBW at first appeared to deny this; he said “Looks like DN is being fed information by another of which PBW’s solicitors are aware, and who has been warned about purveying falsehoods: when PBW’s solicitors can provde (sic) they are false.”. But the case we cite is a matter of public record.9The Law Society/SRA’s interest in Baxendale-Walker appears to have started when the SFO began to investigate the arrangement. In the course of the investigation, Baxendale-Walker was fined £1,000 for contempt of court). The SFO then prosecuted Baxendale-Walker; this prosecution failed after a civil judgment relating to the same matter determined that he had not acted dishonestly. The Law Society then began a lengthy investigation. Baxendale-Walker was cleared of some of the Law Society’s allegations.

He was struck off a year later for a serious conflict of interest – he advised on schemes where large fees were paid to a promoter company which he ultimately controlled.10Again PBW appeared to deny this, but it is once more a matter of public record – the SDT decision is here, and see Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors [2011] EWHC 998 where his appeal was struck out as an abuse of process.11There were other grounds for the application to strike-off PBW, some of which were not upheld. The Law Society’s investigation included commissioning a report into the efficacy of PBW’s tax avoidance schemes, which reached the conclusion that they were ineffective and involved a breach of trust. This was not in the end upheld as a reason for disciplinary action. However we note in passing that PBW obtained an opinion from Robert Venables QC (as was) that the conclusions of the report commissioned by the Law Society were wrong, based on what appear to have been very one-sided instructions. We have previously reported on Mr Venables’ reputation for issuing opinions which turn out to be incorrect, and that was the case here.12PBW says the Law Society was required to pay £200,000 of his costs, and that a costs order was made in interlocutory proceedings before the Master of the Rolls. We do not know if that is true. It is a matter of public record that an initial costs order by the SDT in favour of PBW was overruled by the Court of Appeal in Paul Baxendale Walker v Law Society [2007] EWCA Civ 233. The effect of the Court of Appeal judgment was that the Law Society paid none of PBW’s costs, and PBW was required to pay 60% of the Law Society’s costs. The case has since been widely cited as establishing that there are only very limited circumstances in which the SRA has to pay costs for a failed prosecution.

What’s hard to understand is that, after Baxendale-Walker and his associate Bill Auden were struck-off, promoters kept pushing Baxendale-Walker and his business, Baxendale-Walker LLP. That’s despite Baxendale-Walker’s website clearly describing Baxendale-Walker as a “former barrister and solicitor“, and his history being immediately apparent from a Google search.

See, for example this slide deck, from 2012:13The promoter, Cavendish Knight, appears to no longer exist – it’s not to be confused with the escort agency Cavendish Knights.

Deep in the accompanying FAQ, they say:

Baxendale-Walker was indeed pursuing litigation against the SRA14Paragraph 112 of this case is interesting in what it reveals about PBW’s standard trust scheme and the Law Society, at one stage suing both for £230m.15PBW said to us “PBW never sued the Law Society or SRA in England & Wales”. But Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors [2011] EWHC 998 is a reported case where PBW sued the Law Society in the English High Court. This resulted in an extended civil restraint order being granted to prevent him issuing further claims in England.16PBW says an extended civil restraint order was made against him because he objected to a statutory demand from the Law Society. We do not have a copy of the order, but Judge Briggs in Iain Paul Barker v Paul Baxendale-Walker [2018] EWHC 2518 said “Mr Baxendale-Walker litigated to such an extent that a civil restraint order was made against him.”. And that is the legal position: such an order can only be made when a person has persistently issued claims or made applications which are “totally without merit”. He responded by suing the Law Society and the Solicitors Regulation Authority in California and Virginia, without success.17In both the California and Virginia cases, Baxendale-Walker’s co-claimant was Shahrokh Mireskandari, who had been struck-off by the SRA for acting dishonestly by lying about his qualifications and hiding his criminal convictions in the US for 15 counts of telemarketing fraud. Mireskandari was required to pay costs of £1.4m; his actions had very unfortunate consequences for some of his clients.18Baxendale-Walker denied to us that he had sued in Virginia, but the Virgina court docket is a matter of public record. Baxendale-Walker subsequently failed to pay his California lawyers, resulting in a familiar series of “dilatory” tactics, “obfuscation“, court applications and failed appeals, and Baxendale-Walker being found in contempt of court.

Baxendale-Walker continued to pursue the SRA by impersonating an HMRC official,19Which Baxendale-Walker admitted – see paragraph 80 of Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors for which he pleaded guilty to forgery (fraud) in 2016, and was convicted and fined.

When we told Baxendale-Walker we’d be reporting his fraud conviction, he told us “If you print that you must be sued for defamation, which would be actionable without proof of special damage.” But his conviction in 2016, and the accompanying fine and costs order, were widely reported in the legal and the general press, and were cited as fact in a US court judgment.20We have no first hand knowledge of the fraud trial, and cannot exclude the theoretical possibility that it was misreported, the US court was misled (although the judge says he has seen the conviction certificate) and PBW was not in fact convicted. However that would be quite extraordinary, and (given his proclivity for litigation) PBW’s failure to pursue the media outlets reporting on his conviction would be very hard to understand. If this was the only denial we had received from PBW, we would have taken it more seriously; however the large number of false denials he sent us means that we do not have much difficulty in dismissing it.

That same year, the Rangers scheme was struck down by the Scottish Court of Session – Baxendale-Walker initially denied this was a problem and that HMRC had suffered a “major defeat”, but it became clear very quickly that his game was over. In 2017, the Supreme Court upheld the Court of Session’s decision.

Many of the rest of Baxendale-Walker’s schemes failed – this article by former HMRC inspector Ray McCann gives a very good picture of the mess this left Baxendale-Walker’s former clients in, as does this article from Jersey, and this stream of Jersey cases.

There were a large number of consequential court cases. The most serious for Baxendale-Walker was a negligence claim for £16m from his former client Iain Barker, which resulted in a 2017 Court of Appeal decision that Baxendale-Walker’s advice to Barker had been “clearly negligent”.

The £16m award seems to have caused Baxendale-Walker some financial difficulty. Having previously borrowed from two companies controlled by a client, he now tried to argue that the loans were void and he could keep the money – he failed. Baxendale-Walker failed to pay the now £16.7m owed to Barker, and was made bankrupt in 2018. Baxendale-Walker responded to the bankruptcy with a variety of legal strategems and court applications, all of which failed.21Baxendale-Walker attempted (and failed) to assign rights to sue another law firm to a BVI company he controlled. He attempted (and failed) to stop his bankruptcy trustees from obtaining documentation from third parties (with which he was associated). Baxendale-Walker failed to make full disclosure of his assets to the bankruptcy trustee, and so the usual bankruptcy restrictions were extended for ten more years and remain in place.22PBW plays with words here, he says he “was released from bankruptcy after the standard 1 year period”. This is correct, but the restrictions period was extended by ten years because of his failure to make full and frank disclosure, and lapses in 2030. This is a matter of public record and confirmed by a public statement by the Official Receiver. PBW says “the bankruptcy trustees [were] satisfied that they had established all of PBW assets, income and sources of income”. But the Official Receiver said he failed to make a full and frank disclosure of his affairs, failed to disclose interests in property, and under-declared his income. This is a matter of public record.23PBW’s response to the bankruptcy was such that PBW’s bankruptcy trustee applied for a limited civil restraint order. This was refused, but the judge said there was “material which is well capable of forming a basis” for a general civil restraint order to be granted by the High Court. We do not know if such an application was made.

Along the way, Baxendale-Walker made at least half a dozen different court claims against a former partner to recover gifts he had made to her.24Baxendale-Walker’s evidence to the Court in one of those cases was: “She was never anything more than a TV stripper and glamour model, who provided sex and occasional companionship in exchange for a comfortable and conditional standard of living which I procured for her. … She is only one of more than a dozen girls for whom I procure the provision [of] housing, cars and other benefits. The provision is always conditional on my satisfaction with the relationship. As soon as I am no longer satisfied, the use benefits are withdrawn.” Baxendale-Walker’s claims all failed, and were summarised by one judge as a “use of the court’s process for ulterior and illegitimate motives“.

Baxendale-Walker says he retired in 2013 on grounds of ill-health, was diagnosed with cerebral vasculitis in 2015, and since then has suffered a number of cerebral stroke events.25PBW told a US court in 2015 he was too disabled to be able to participate in the proceedings; the judge disagreed. He says he re-trained as a psychologist and psychotherapist and publishes books under the name of Paul Chaplin.

All of this is a brief and incomplete summary of an astonishing career.26We have barely touched on the large number of court and tribunal cases involving Baxendale-Walker (directly or indirectly), some relating to proceedings around the world, others much closer to home. There’s more material in PBW’s Wikipedia article, but the accuracy is questionable, and it stops around 2016, and therefore misses out the Rangers judgment which collapsed Baxendale-Walker’s house of cards. We would add that we very much doubt this YouTube channel, this Facebook account or this Twitter account are actually operated by PBW.

It’s hard to explain how someone so peculiar, and with so many legal troubles, could have been treated as an expert27This textbook, 2012 edition, is still available for £150. We’d be interested to know how many sales it makes. PBW also wrote a book on “purpose trusts”, sadly out of print, in which he argued that English law should recognise private non-charitable purpose trusts. In our view there is obvious potential for abuse of such entities, were they permitted. by people who should have known better, trusted by the likes of Rangers28The otherwise comprehensive Wikipedia article on the collapse of Rangers is curiously light on how the club came to sign up to the schemes.and ended up causing so much damage to the tax system and to many peoples’ lives.

The HMRC investigation

There is a great deal of anger, among his former clients, HMRC personnel and many tax professionals, that Paul Baxendale-Walker appears to have escaped responsibility for his actions. It’s understandable that HMRC should look for every opportunity to recover tax and penalties from him.29It’s possible there was activity in the late 2010s – an appeal was filed by Baxendale-Walker in 2019 against HMRC and the Official Receiver; but we don’t know what it concerned, and it doesn’t appear to have progressed. We would guess (and it’s only a guess) that PBW tried to sue HMRC and the Official Receiver, failed (in an unreported case) and this is the appeal he made, which he didn’t progress.

HMRC investigations are usually confidential, but thanks to US court documents30The content of this section comes from the US court papers. The IRS’s initial application is here. The response from Baxendale-Walker’s associate is here (it misunderstands the bankruptcy point we mentioned in the previous footnote; it also makes the very odd claim that it’s hearsay for the IRS to cite HMRC’s reasons for their request). The court judgment is here – the judge found in favour of the IRS, and disposed of the LLC’s arguments in not much more than a sentence. An order was made requiring production of the documents. we can reveal that HMRC started investigating Baxendale-Walker’s own historic personal tax affairs at some point around 2018.31Of course there could have been earlier investigations of which we are unaware.

In the court documents, the IRS says HMRC claimed that, from 2007 to 201832The effect of bankruptcy is (very broadly) to eliminate historic debt. A well-advised bankrupt therefore ensures that all of his or her affairs are in order with HMRC before becoming bankrupt: not necessarily paying all the tax that’s due, but making sure all the tax that’s due has been legally assessed by HMRC (so it is then wiped out by the bankruptcy). It looks like Baxendale-Walker didn’t do this. If HMRC assesses 2007-2018 tax today, then that becomes a liability today, and isn’t affected by his previous bankruptcy., the total tax avoided using Baxendale-Walker’s schemes was £1bn,33We are surprised by this number. The loan charge was said by HMRC to collect £3bn. There were many other promoters pushing these schemes; it would be astonishing if PBW is responsible for one third of that. There are several possible explanations. One is that HMRC are simply wrong. Another is that the amount includes avoidance that the loan charge can’t counter for some reason. Another is that the figure includes avoidance entirely unrelated to loan schemes. We asked PBW about this; his response was to deny any knowledge of the tax avoided by schemes on which he advised. and that he used the same schemes to avoid tax on his fees. HMRC claim that £51m went into Baxendale-Walker’s own remuneration trust. But given Baxendale-Walker’s usual fees34As reported in the cases cited above were 10% of the amounts put under trust, and the tax benefit was around half the amount put into trust, it seems reasonable to assume from this Baxendale-Walker’s total remuneration was much higher – potentially over £200m. And this is consistent with Baxendale-Walker’s own claim when he sued the Law Society back in 2011 – he was trying to recover £230m of lost personal revenue. The tax at stake could, therefore, be very large indeed.35Baxendale-Walker denies this. He told us “These facts do not properly lend themselves to a bizarre allegation that PBW is a multi-millionaire Machiavelli, operating a vast empire of tax avoidance businesses. The allegation is manifestly a fantasy. It is one which HMRC themselves no longer ascribe to, according to Court documents filed in 2024 in another case which does not involve PBW. PBW’s solicitor has possession of those documents, which are confidential and will not be disclosed to Dan Neidle.” But we have no evidence that these documents exist. The fees received by entities connected to PBW are a matter of public record; and PBW’s denial is contradicted by his own claim for £230m from the Law Society.

Baxendale-Walker says he “accounted for and paid all due tax on [his] fees. HMRC has never alleged anything different.”. That is untrue. The document the IRS filed with the US court says that HMRC “believes Walker used these same schemes to avoid paying tax on the significant fees he earned from their sales”.36PBW replied to this saying that the IRS withdrew its case in Federal Court. We have no evidence of that; but even if it did, PBW’s claim that HMRC never alleged he hadn’t paid tax is false, and we expect he made it because he didn’t realise we had access to the US court documents.37There is another potential avenue for HMRC. We understand PBW believes that Baxendale Walker LLP’s accounting profits were “rectified” (which is to say, reduced) following a 2015 judgment of the Belize Supreme Court that it actually held substantial amounts as fiduciary for Minerva. We have not located that judgment – it may or not be connected with this 2017 Belize Court of Appeal judgment. We do not know if the accounts were retrospectively “rectified” in this manner. However, we would ordinarily expect HMRC to challenge a retrospective contention that a large amount received by a UK LLP with UK members, and booked in its accounts, was actually received as fiduciary for an offshore entity. We do not know if they did.

HMRC alleges that Baxendale-Walker was uncooperative with HMRC’s enquiries, and sought to frustrate its investigation. In particular, HMRC says that in 2013 he tried to hide evidence by selling the assets of his business, Baxendale-Walker LLP, including his records, to Hawk Consultants LLP, a US LLC entity. Baxendale-Walker tells us that he is being persecuted by HMRC, who lied to the IRS. He said:

“it is not ‘unusual’ that the rump business, including all papers, of an LLP which has ceased to trade, are sold to its ultimate owner entity, so that the LLP can be wound up properly.”

But in 2013, Baxendale-Walker LLP’s only registered members were PBW and Sargespace Limited (which was wholly owned by PBW). In June 2014, a form was filed with Companies House retrospectively appointing Belize Offshore Services Limited as member from 1 July 2013 and retrospectively removing PBW and Sargespace as members from the same date. In January 2015, a form was filed Companies House retrospectively appointing Hawk Consultants LLP as member as of 1 July 2013. This is highly unusual.

We cannot be sure whether HMRC or Baxendale-Walker is telling the truth. However it is our opinion, based on the known facts and Baxendale-Walker’s well-documented history of obstruction, that HMRC are correct and Baxendale-Walker did attempt to frustrate HMRC’s investigation.

The US court application was made by the IRS, after HMRC used the tax treaty between the US and the UK to request that the IRS obtain the records from the LLC. The IRS issued a summons and, despite an attempt to contest it, a court order compelled production of the documents. PBW told us that the IRS withdrew its case: we do not know if that is correct (and it’s not clear to us how that could happen after the court order had been issued).

We don’t know what happened subsequently, but these events may have led to HMRC making more specific information requests in the UK.

Baxendale-Walker told us:

“I was never subject to any amended or discovery assessment for tax in this jurisdiction in relation to the tax properly paid on my drawings from Baxendale Walker LLP.“

We don’t know what this means. Clearly you can’t be subject to a discovery assessment “in relation to tax properly paid”, but we don’t know if that is loose wording and Baxendale-Walker is saying there’s never been an enquiry or discovery assessment at all, or if instead this is a a very specific denial.

The £14m penalty

On 10 January 2022, HMRC successfully obtained an “information notice” from a UK tax tribunal against Baxendale-Walker, requiring him to provide HMRC with information about (we believe) both the tax affairs of Baxendale-Walker himself, and those of other entities (possibly his clients; possibly Minerva and/or the other companies with which he’s been linked).38We infer this because an information notice seeking information from a taxpayer about the same taxpayer can be issued straightforwardly by an HMRC official – it doesn’t require a tribunal to be involved. However the penalty provisions used by HMRC only relate to tax of the subject of the information notice. Hence it is our belief (based on experience and the legislation) that the information notice both related to Baxendale-Walker himself and third parties.

The information notice required Baxendale-Walker to provide the information by 11 March 2022.39Baxendale-Walker claimed to us that the information notice was invalid because he did not have the information. That is an elementary legal mistake on his part; an information notice is valid regardless of whether the subject holds the information; but an information notice only requires a person to produce a document if it’s within their “possession or power“. Hence the proper response to an information notice, if you don’t possess the document, is to formally respond to HMRC and explain that you don’t have it. If, alternatively, PBW really believed the information notice was invalid, it is hard to explain why he didn’t make that point at the time, rather than seeking a series of extensions.

At this point something unfortunate and perhaps improper happened. HMRC waited four days to serve the information notice on Baxendale-Walker, and then (without permission of the tribunal) updated the deadline on the notice to 15 March 2022, to reflect that delay. It’s possible that this invalidated the penalty discussed in this article, but that’s a point the parties parked for the moment – it’s not HMRC’s main failing.

Information notices are usually taken very seriously by taxpayers, and nobody in our team has seen a client even suggest simply not complying with them. That, however, was how Baxendale-Walker appears to have proceeded:

- Right before the new deadline expired, on 15 March 2022, Baxendale-Walker’s lawyers asked for an extension to 29 March 2022. Rather generously, HMRC agreed. Then on 28 March 2022 they asked for another 14 day extension; which HMRC understandably did not grant.

- Having received nothing from Baxendale-Walker, HMRC issued a £300 penalty on 29 March. This was under paragraph 39 of Schedule 36 Finance Act 2008. By May, HMRC had still not received a response – daily penalties had reached £1,800.

- On 1 March 2023 (i.e. almost a year later), for reasons that are unclear40Possibly PBW had appealed the penalties and the amounts involved were too small for HMRC to want to bother with?, HMRC wrote to him withdrawing all previous penalties and providing a further 14 days for full compliance with the information notice, i.e. giving him until 15 March 2023.

- Having still received nothing, HMRC issued a new paragraph 39 penalty on 15 March 2023.

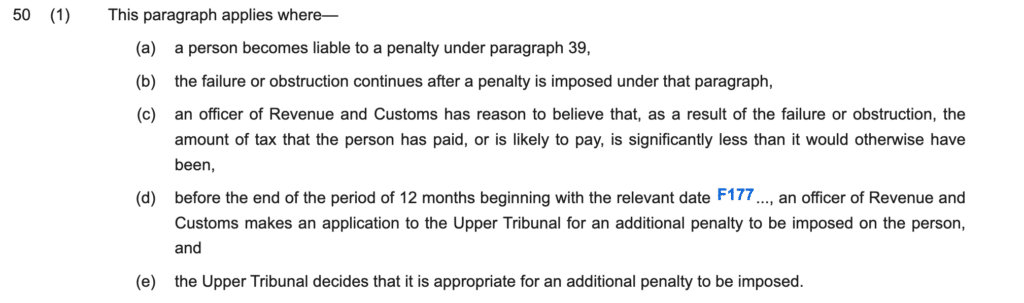

- Finally, on 28 March 2023, HMRC applied to the Upper Tribunal to impose a penalty under the separate provision in paragraph 50. This enables a penalty to be charged based on the amount of tax at stake. HMRC’s claim was for £14m – at this point we don’t know how that was calculated, or what the underlying avoidance was.

The Upper Tribunal now had to decide whether to impose the £14m penalty under paragraph 50.

But there was a problem. Here’s the legislation:

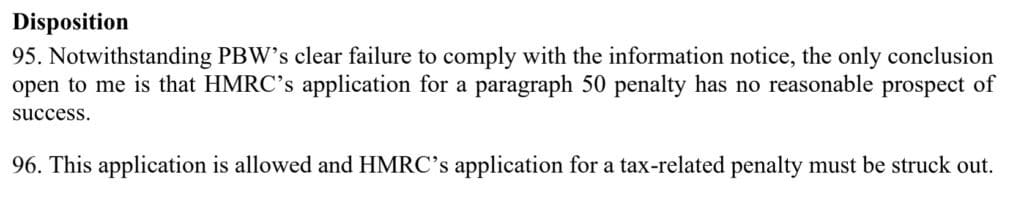

At this point everything goes wrong for HMRC (the judgment is here):

- If HMRC’s decision on 1 March 2023 to cancel penalties and give Baxendale-Walker more time amounted to a variation of the original 2022 information notice, then the penalty HMRC imposed on 15 March 2023 was invalid, because the time for compliance had not yet expired. So there was no valid paragraph 39 penalty, and therefore no possibility of a paragraph 50 penalty.

- If, on the other hand, the 1 March 2023 decision was just giving Baxendale-Walker an informal grace period under the original information notice and not changing the formal compliance deadline (which in our view is the more likely result) then more than a year had passed, and the condition in paragraph 50(1)(d) was failed. There was, again, no possibility of a paragraph 50 penalty.

- That’s in addition to the possibility that HMRC’s original change to the deadline in the 2022 information notice, without the Tribunal’s authority, rendered the information notice invalid (the Upper Tribunal didn’t need to decide this point, given HMRC had already failed to apply the penalty; we have not considered this point either).

It appears that the judge41Mark Baldwin, a very experienced and respected tax partner at law firm Macfarlanes was unhappy with this outcome:

The Upper Tribunal gave judgment back in July 2023 – it appears as if either HMRC or Baxendale-Walker tried to prevent publication; it was eventually published on 3 June 2024 with the name of the HMRC official removed.

What went wrong

There were at least five serious failures by HMRC:

- HMRC should not have amended the deadline in the information notice without the Tribunal’s permission.

- HMRC shouldn’t have waited a year once it became clear Baxendale-Walker was not complying with the information notice – the standard £60 penalty was clearly inadequate. HMRC is able to apply to a tribunal to increase the daily penalty from £60 to up to £1,000 – it should have used these powers.

- HMRC should not have set a new deadline on 1 March 2023; it was an unnecessary step which (foreseeably) created legal problems.

- However, once HMRC had decided to go down the path of allowing Baxendale-Walker more time, it should have been made clear that this was an exercise of HMRC’s discretionary “care and management” powers and the original information notice remained in force.

- HMRC should have procedures to track the elapsed time after paragraph 39 penalties are issued, so that paragraph 50 penalties can be assessed well within the one year deadline. The importance of statutory deadlines is something that’s drilled into trainee lawyers; but it appears that HMRC either had no such procedures, or they were insufficient.

HMRC may have lost all hope of obtaining a £14m penalty, but that does not mean they should give up on obtaining the information they were seeking. We would very much hope that, when the judgment was issued last year, HMRC responded by immediately issuing a fresh information notice42Thus avoiding any arguments about the status of the original notice, and following that up carefully and aggressively. We do not know if this is what happened.

Why did HMRC fail?

Conversations with HMRC insiders suggest there is a wider problem with a lack of resources, a lack of experienced staff, and inadequate systems and training.

In the Baxendale-Walker case, one officer was involved throughout43That officer being the individual whom HMRC wishes to protect by redacting their name from the judgment.; it is unclear if they were appropriately supervised, given the seriousness of the matter. The information notice legislation is not terribly complex, but there are some pitfalls which can catch out the inexperienced.

We asked HMRC for comment – they responded that:

“We continue to robustly tackle promoters. We have safeguards in place to ensure future penalties are issued within the time limits”

… which looks like an admission that there were insufficient safeguards in place in 2023.

However it seems that whatever new safeguards were put in place are inadequate.

We are aware of an avoidance case just two days ago (not yet reported) where HMRC submitted their bundle of authorities just over two hours late (19:05 rather than by 17:00 on Monday). There was an “unless” order which meant that the case would be struck out unless the authorities bundle was submitted on time. And so at 17:01 on Monday the case was struck out automatically.

Once again, the current law and practice of HMRC seems insufficient to deal with bad actors. We’ll be writing more about this soon.

Baxendale-Walker’s response

We asked Baxendale-Walker for comment.

The letter he sent us was extraordinary.

First, he denied a series of established facts about his history, including the fact he was struck-off and the fact he was convicted of fraud (we’ve footnoted some of the key denials). He specifically denies promoting tax avoidance schemes, and says he was just an adviser. However it is reasonably clear that Baxendale-Walker had a financial interest in FSL, the entity promoting his structures in the 90s and early 2000s – this was in fact the reason he was struck off.44All of this is set out in the judgment in Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors. PBW originally claimed he wasn’t the controlling influence of FSL or the beneficial owner of it. The SDT found that he did have control over FSL, and received substantial sums from it. When PBW appealed against that decision, he asked his “effective ownership” of FSL to be “taken as correct” by the court, but said it didn’t amount to a conflict of interest (see paragraph 50). PBW subsequently withdrew his appeal. It is also reasonably clear from reported cases that he had an interest in Minerva45PBW’s letter to us talks about a “Minerva community” as if it is independent from him. The facts do not bear this out. and Buckingham Wealth46(which appears to have no internet presence; the various other Buckingham Wealth companies found by a Google search have no connection to Baxendale-Walker), the entities promoting his structures more recently.47The judgment in Northwood v HMRC [2023] UKFTT 351 (TC) includes the text of an engagement letter between Baxendale Walker LLP and a client, which includes an appendix saying that “MINERVA” is a separate business of Baxendale-Walker LLP, which sells and markets strategies devised by Baxendale-Walker LLP. MINERVA’s fees were 10% for every contribution to the trust. PBW therefore most certainly knew what fees Minerva was making and, on the basis of the text from his own engagement letter, he benefited from those fees.48The judgment in Dukeries Healthcare Limited [2021] EWHC 2086 (Ch) describes “Minerva” as an “associated company” of Baxendale-Walker LLP. Again, the Baxendale-Walker LLP engagement letter provided for a fee equal to 10% of each trust contribution to be paid to Minerva.49As part of US litigation unrelated to the matters discussed in this report, a deed was disclosed under which Baxendale-Walker LLP says it holds sums as bare trustee for Minerva Services Limited50The judgment in CIA Insurance Services v Commissioners for HMRC also refers to a Baxendale-Walker LLP engagement letter where 10% of each trust contribution was to be paid to Minerva.51The judgment in Iain Paul Barker v Paul Baxendale-Walker notes that “As to [PBW’s] claim about lack of resources the Court was struck by three companies willing to financially assist Mr Baxendale-Walker, including his own remuneration trust, EW LLP, Minerva Ltd, Hawk, Brunswick Wealth and Burleigh House PTC Ltd.”52The judgment in Paul Baxendale-Walker v APL Management Limited [2018] EWHC 543 states that, in May 2015, Baxendale Walker issued a claim “in respect of various fees that he alleged were owed to his companies (Baxendale Walker LLP and Minerva Services Ltd)” (my emphasis). That same case reports Minerva Services Limited (BVI), Minerva Services Limited (Belize) and Buckingham Wealth Ltd acting on behalf of PBW.53There has been other litigation involving Minerva, the background to which is not clear to us, involving a Pankim Kumar Patel suing Minerva Services (Delaware) Inc, PBW himself and one other individual. The judgment is here. A witness statement is here, giving more of the background and with much criticism of PBW (although of course, as a witness statement, it must be taken with a pinch of salt).54A series of companies that may be related appear to be engaged in ongoing litigation, much of which relates around purported assignments to new entities, and PBW continues to be involved in litigation personally.

We would strongly recommend reading Baxendale-Walker’s communication with us in full. The black text is from an email we sent to him; the blue text is his response. It refers in places to an earlier communication which we agreed we would not publish (and this is why it starts with point 9). We have redacted parts of the correspondence relating to matters we will be covering at a later date.

PDF version here, and clickable thumbnails below:

Second, he accused our founder, Dan Neidle, of committing the criminal offence of harassment by emailing him for comment. Dan was replying to an email Baxendale-Walker had sent him, after Dan sent a message to Baxendale-Walker’s solicitors asking for contact details.

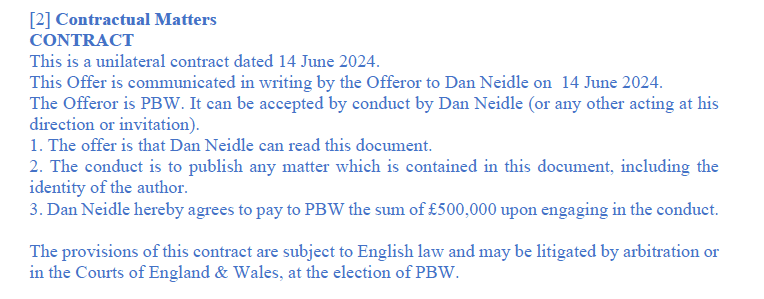

Third, Baxendale-Walker was keen that we didn’t publish his denials, and so constructed a “unilateral contract” that purported to charge Dan £500,000 if we did:

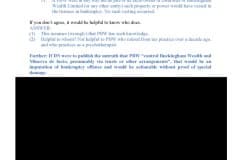

We believe a first year law student would be able to identify why this is ineffective. Our response to Morr & Co, Baxendale-Walker’s solicitors, summarised the position as follows:

![27. This attempt to constrain my actions is wholly without merit; indeed it is childish game-playing.

28. I said in the prior email that I intended to publish any response; if PBW did not wish his words

to be published, he should not have replied to me.

29. Needless to say, PBW’s “offer” is not accepted. Whilst a contract can be accepted by conduct,

that is only if the conduct in question is intended to constitute acceptance. Here it is not (see

Reveille Independent LLC v Anotech International (UK) Ltd [2016] EWCA Civ 443)

30. In any event, the purported contract would fail for lack of consideration: I was free to read the

document and publish it as soon as I received it. I did not need PBW’s consent to do so.

31. I expect you agree with me on this. If not, please take this letter as a unilateral offer that you can

reply to this letter for a fee of £1bn, and you will accept that offer by conduct if you reply.](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-100.png)

Our complete response to Morr & Co is available here as a PDF, or clickable thumbnails below:

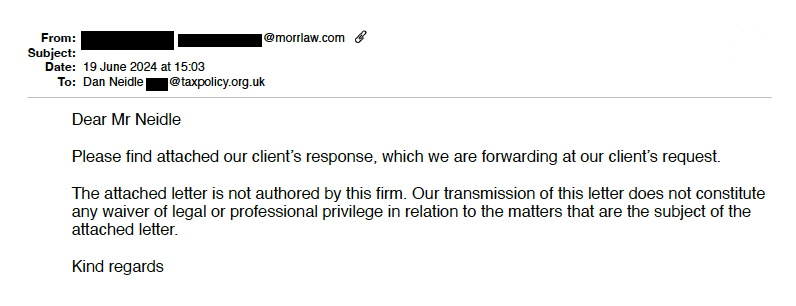

Morr & Co didn’t reply themselves – they sent this covering email

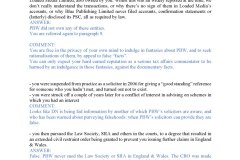

In his attached letter, Baxendale-Walker denies that he was previously denying his suspension and striking-off (although it seems clear that he was). He claims that holding various entities as nominee meant that he was not lying when he said he didn’t own them, and says that the bankruptcy trustee accepted he held as nominee. We don’t know if this is true, and it begs the question as to who the ultimate owner was. His response is available here as a PDF, or clickable thumbnails below. We have again redacted parts of the correspondence relating to matters we will be covering at a later date:

Baxendale-Walker’s tactic throughout all the many disputes he’s been involved in has been to obfuscate, and we expect that’s what he’s doing here.

The wider failure to stop promoters

Baxendale-Walker is an extreme case, but by far from the only one. HMRC has consistently failed to penalise promoters of tax avoidance schemes; that is all the more unfortunate when, at the same time, it aggressively pursues the clients of their failed schemes.

We believe the law needs to change so that promoters become personally, and potentially criminally, liable for the failure of their schemes. But that isn’t enough – HMRC itself needs to change. There’s no point having a wide array of powers if they’re not used competently and effectively.

Many thanks to K and I for their insight and research on this report, and to L, J and M for further technical input.

(We rely on an informal team of experts across the legal and tax profession; accountants, solicitors, ICs and retired HMRC officials. Most have to remain anonymous for professional reasons; but Tax Policy Associates would not exist without them.)

Photo by Paul Baxendale-Walker, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, and edited (for aspect ratio, adding filler image to the left and right edge using generative AI) by Tax Policy Associates Ltd

- 1Baxendale-Walker denied this to us, and claims his advice was not followed. He told Channel 4 News that he hadn’t advised Rangers at all; “somebody” had advised Rangers, using his book. But the Supreme Court itself said that Baxendale-Walker devised and operated the Rangers scheme.

- 2The fact that the loans would never be repaid is often denied by scheme promoters, and PBW has denied it to us. But it is in fact inevitable. The loans were clearly a substitute for employee wages – instead of receiving £100,000 of taxed income, the employee would receive a £100,000 supposedly untaxed loan. Great. But if the employee repays the loan, they have nothing. The trust that received the loan repayment would typically be prohibited from returning any money to the employee. This was never an outcome that people would want or accept. We have reviewed dozens of loan schemes and hundreds of loans, and spoken to hundreds of scheme users – none ever saw a loan repaid, and (before the schemes collapsed) none thought that was a realistic outcome.

- 3PBW has denied to us that he owned Loaded – he says he never owned Loaded Media Limited or Blue Publishing Limited. But Companies House filings show him as the sole shareholder of both companies, and of the related production company Bluebird Productions Limited. PBW’s acquisition of Loaded and his involvement with Bluebird Productions Limited was widely reported at the time in the legal and general press. When we put this to PBW, he says he was merely a nominee. PBW was registered as the person with significant control of Bluebird Productions Limited up until the point it dissolved in 2019 (which suggests he was not a nominee). Blue Publishing Limited remains in existence, with PBW the sole director and company secretary; no PSC has been registered, which appears to be a breach of company law by PBW (whether or not he was a nominee). Loaded Media Limited was dissolved in December 2016; a PSC should have been registered from April 2016 but there again appears to have been a breach of company law by PBW.

- 4Lawyers and other tax advisers usually charge by the hour, or sometimes with a fixed fee. Tax avoidance scheme promoters often charge by reference to the value of the tax benefit (explicitly or implicitly). A fee equal to 10% of the value of the property – not the benefit, but the property – is astonishingly high.

- 5Even before more aggressive anti-avoidance rules were introduced in 2010, we believe the loan schemes all failed. In some cases they were shams. Even when they weren’t, there were two very serious problems with the structure. First, the “loans” were not really loans, as there was no intention to repay them. HMRC and the courts sadly took a long time to understand this. Second, most of the loan scheme trusts excluded all the intended beneficiaries (to avoid a tax charge) but the trustees nevertheless made interest free “loans” to these people, despite the fact that this was clearly a benefit. Their argument was that an interest free loan was not a benefit – we would say that is plainly incorrect, and we therefore agree with those who say the trustees must have acted in breach of trust. Anyone who disagrees is welcome to make a large interest free loan with no repayment date to Tax Policy Associates Ltd.

- 6We have heard from several sources that PBW never put any of his advice in writing, relying on his ability to “persuade” clients that the attractiveness of his loan trust suggestion spoke for itself. Most of the tax avoidance scheme promoters we’ve written about took a similar approach.

- 7The avoidance schemes weren’t limited to tax; Baxendale-Walker was also involved in a scheme that purported to enable people to access their pensions before retirement (a so-called “pension liberation scheme“). The Pension Regulator’s position was that the scheme constituted misuse or misappropriation of the pension assets, and in 2014 they applied for an injunction against him and others involved. Baxendale-Walker appeared at the court hearing on the first day representing himself. He announced that there were “many more remunerative things” he could do with his time than attend the court, and declined to attend subsequent days. This worked about as well as one would expect, with the court ruling that Baxendale-Walker’s interpretations of the law were incorrect; he and the other defendants then agreed to discontinue the schemes.

- 8PBW at first appeared to deny this; he said “Looks like DN is being fed information by another of which PBW’s solicitors are aware, and who has been warned about purveying falsehoods: when PBW’s solicitors can provde (sic) they are false.”. But the case we cite is a matter of public record.

- 9The Law Society/SRA’s interest in Baxendale-Walker appears to have started when the SFO began to investigate the arrangement. In the course of the investigation, Baxendale-Walker was fined £1,000 for contempt of court). The SFO then prosecuted Baxendale-Walker; this prosecution failed after a civil judgment relating to the same matter determined that he had not acted dishonestly. The Law Society then began a lengthy investigation. Baxendale-Walker was cleared of some of the Law Society’s allegations.

- 10Again PBW appeared to deny this, but it is once more a matter of public record – the SDT decision is here, and see Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors [2011] EWHC 998 where his appeal was struck out as an abuse of process.

- 11There were other grounds for the application to strike-off PBW, some of which were not upheld. The Law Society’s investigation included commissioning a report into the efficacy of PBW’s tax avoidance schemes, which reached the conclusion that they were ineffective and involved a breach of trust. This was not in the end upheld as a reason for disciplinary action. However we note in passing that PBW obtained an opinion from Robert Venables QC (as was) that the conclusions of the report commissioned by the Law Society were wrong, based on what appear to have been very one-sided instructions. We have previously reported on Mr Venables’ reputation for issuing opinions which turn out to be incorrect, and that was the case here.

- 12PBW says the Law Society was required to pay £200,000 of his costs, and that a costs order was made in interlocutory proceedings before the Master of the Rolls. We do not know if that is true. It is a matter of public record that an initial costs order by the SDT in favour of PBW was overruled by the Court of Appeal in Paul Baxendale Walker v Law Society [2007] EWCA Civ 233. The effect of the Court of Appeal judgment was that the Law Society paid none of PBW’s costs, and PBW was required to pay 60% of the Law Society’s costs. The case has since been widely cited as establishing that there are only very limited circumstances in which the SRA has to pay costs for a failed prosecution.

- 13The promoter, Cavendish Knight, appears to no longer exist – it’s not to be confused with the escort agency Cavendish Knights.

- 14Paragraph 112 of this case is interesting in what it reveals about PBW’s standard trust scheme

- 15PBW said to us “PBW never sued the Law Society or SRA in England & Wales”. But Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors [2011] EWHC 998 is a reported case where PBW sued the Law Society in the English High Court.

- 16PBW says an extended civil restraint order was made against him because he objected to a statutory demand from the Law Society. We do not have a copy of the order, but Judge Briggs in Iain Paul Barker v Paul Baxendale-Walker [2018] EWHC 2518 said “Mr Baxendale-Walker litigated to such an extent that a civil restraint order was made against him.”. And that is the legal position: such an order can only be made when a person has persistently issued claims or made applications which are “totally without merit”.

- 17In both the California and Virginia cases, Baxendale-Walker’s co-claimant was Shahrokh Mireskandari, who had been struck-off by the SRA for acting dishonestly by lying about his qualifications and hiding his criminal convictions in the US for 15 counts of telemarketing fraud. Mireskandari was required to pay costs of £1.4m; his actions had very unfortunate consequences for some of his clients.

- 18Baxendale-Walker denied to us that he had sued in Virginia, but the Virgina court docket is a matter of public record.

- 19Which Baxendale-Walker admitted – see paragraph 80 of Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors

- 20We have no first hand knowledge of the fraud trial, and cannot exclude the theoretical possibility that it was misreported, the US court was misled (although the judge says he has seen the conviction certificate) and PBW was not in fact convicted. However that would be quite extraordinary, and (given his proclivity for litigation) PBW’s failure to pursue the media outlets reporting on his conviction would be very hard to understand. If this was the only denial we had received from PBW, we would have taken it more seriously; however the large number of false denials he sent us means that we do not have much difficulty in dismissing it.

- 21Baxendale-Walker attempted (and failed) to assign rights to sue another law firm to a BVI company he controlled. He attempted (and failed) to stop his bankruptcy trustees from obtaining documentation from third parties (with which he was associated).

- 22PBW plays with words here, he says he “was released from bankruptcy after the standard 1 year period”. This is correct, but the restrictions period was extended by ten years because of his failure to make full and frank disclosure, and lapses in 2030. This is a matter of public record and confirmed by a public statement by the Official Receiver. PBW says “the bankruptcy trustees [were] satisfied that they had established all of PBW assets, income and sources of income”. But the Official Receiver said he failed to make a full and frank disclosure of his affairs, failed to disclose interests in property, and under-declared his income. This is a matter of public record.

- 23PBW’s response to the bankruptcy was such that PBW’s bankruptcy trustee applied for a limited civil restraint order. This was refused, but the judge said there was “material which is well capable of forming a basis” for a general civil restraint order to be granted by the High Court. We do not know if such an application was made.

- 24Baxendale-Walker’s evidence to the Court in one of those cases was: “She was never anything more than a TV stripper and glamour model, who provided sex and occasional companionship in exchange for a comfortable and conditional standard of living which I procured for her. … She is only one of more than a dozen girls for whom I procure the provision [of] housing, cars and other benefits. The provision is always conditional on my satisfaction with the relationship. As soon as I am no longer satisfied, the use benefits are withdrawn.”

- 25PBW told a US court in 2015 he was too disabled to be able to participate in the proceedings; the judge disagreed.

- 26We have barely touched on the large number of court and tribunal cases involving Baxendale-Walker (directly or indirectly), some relating to proceedings around the world, others much closer to home. There’s more material in PBW’s Wikipedia article, but the accuracy is questionable, and it stops around 2016, and therefore misses out the Rangers judgment which collapsed Baxendale-Walker’s house of cards. We would add that we very much doubt this YouTube channel, this Facebook account or this Twitter account are actually operated by PBW.

- 27This textbook, 2012 edition, is still available for £150. We’d be interested to know how many sales it makes. PBW also wrote a book on “purpose trusts”, sadly out of print, in which he argued that English law should recognise private non-charitable purpose trusts. In our view there is obvious potential for abuse of such entities, were they permitted.

- 28The otherwise comprehensive Wikipedia article on the collapse of Rangers is curiously light on how the club came to sign up to the schemes.

- 29It’s possible there was activity in the late 2010s – an appeal was filed by Baxendale-Walker in 2019 against HMRC and the Official Receiver; but we don’t know what it concerned, and it doesn’t appear to have progressed. We would guess (and it’s only a guess) that PBW tried to sue HMRC and the Official Receiver, failed (in an unreported case) and this is the appeal he made, which he didn’t progress.

- 30The content of this section comes from the US court papers. The IRS’s initial application is here. The response from Baxendale-Walker’s associate is here (it misunderstands the bankruptcy point we mentioned in the previous footnote; it also makes the very odd claim that it’s hearsay for the IRS to cite HMRC’s reasons for their request). The court judgment is here – the judge found in favour of the IRS, and disposed of the LLC’s arguments in not much more than a sentence. An order was made requiring production of the documents.

- 31Of course there could have been earlier investigations of which we are unaware.

- 32The effect of bankruptcy is (very broadly) to eliminate historic debt. A well-advised bankrupt therefore ensures that all of his or her affairs are in order with HMRC before becoming bankrupt: not necessarily paying all the tax that’s due, but making sure all the tax that’s due has been legally assessed by HMRC (so it is then wiped out by the bankruptcy). It looks like Baxendale-Walker didn’t do this. If HMRC assesses 2007-2018 tax today, then that becomes a liability today, and isn’t affected by his previous bankruptcy.

- 33We are surprised by this number. The loan charge was said by HMRC to collect £3bn. There were many other promoters pushing these schemes; it would be astonishing if PBW is responsible for one third of that. There are several possible explanations. One is that HMRC are simply wrong. Another is that the amount includes avoidance that the loan charge can’t counter for some reason. Another is that the figure includes avoidance entirely unrelated to loan schemes. We asked PBW about this; his response was to deny any knowledge of the tax avoided by schemes on which he advised.

- 34As reported in the cases cited above

- 35Baxendale-Walker denies this. He told us “These facts do not properly lend themselves to a bizarre allegation that PBW is a multi-millionaire Machiavelli, operating a vast empire of tax avoidance businesses. The allegation is manifestly a fantasy. It is one which HMRC themselves no longer ascribe to, according to Court documents filed in 2024 in another case which does not involve PBW. PBW’s solicitor has possession of those documents, which are confidential and will not be disclosed to Dan Neidle.” But we have no evidence that these documents exist. The fees received by entities connected to PBW are a matter of public record; and PBW’s denial is contradicted by his own claim for £230m from the Law Society.

- 36PBW replied to this saying that the IRS withdrew its case in Federal Court. We have no evidence of that; but even if it did, PBW’s claim that HMRC never alleged he hadn’t paid tax is false, and we expect he made it because he didn’t realise we had access to the US court documents

- 37There is another potential avenue for HMRC. We understand PBW believes that Baxendale Walker LLP’s accounting profits were “rectified” (which is to say, reduced) following a 2015 judgment of the Belize Supreme Court that it actually held substantial amounts as fiduciary for Minerva. We have not located that judgment – it may or not be connected with this 2017 Belize Court of Appeal judgment. We do not know if the accounts were retrospectively “rectified” in this manner. However, we would ordinarily expect HMRC to challenge a retrospective contention that a large amount received by a UK LLP with UK members, and booked in its accounts, was actually received as fiduciary for an offshore entity. We do not know if they did.

- 38We infer this because an information notice seeking information from a taxpayer about the same taxpayer can be issued straightforwardly by an HMRC official – it doesn’t require a tribunal to be involved. However the penalty provisions used by HMRC only relate to tax of the subject of the information notice. Hence it is our belief (based on experience and the legislation) that the information notice both related to Baxendale-Walker himself and third parties.

- 39Baxendale-Walker claimed to us that the information notice was invalid because he did not have the information. That is an elementary legal mistake on his part; an information notice is valid regardless of whether the subject holds the information; but an information notice only requires a person to produce a document if it’s within their “possession or power“. Hence the proper response to an information notice, if you don’t possess the document, is to formally respond to HMRC and explain that you don’t have it. If, alternatively, PBW really believed the information notice was invalid, it is hard to explain why he didn’t make that point at the time, rather than seeking a series of extensions.

- 40Possibly PBW had appealed the penalties and the amounts involved were too small for HMRC to want to bother with?

- 41Mark Baldwin, a very experienced and respected tax partner at law firm Macfarlanes

- 42Thus avoiding any arguments about the status of the original notice

- 43That officer being the individual whom HMRC wishes to protect by redacting their name from the judgment.

- 44All of this is set out in the judgment in Paul Baxendale-Walker v Middleton & Ors. PBW originally claimed he wasn’t the controlling influence of FSL or the beneficial owner of it. The SDT found that he did have control over FSL, and received substantial sums from it. When PBW appealed against that decision, he asked his “effective ownership” of FSL to be “taken as correct” by the court, but said it didn’t amount to a conflict of interest (see paragraph 50). PBW subsequently withdrew his appeal.

- 45PBW’s letter to us talks about a “Minerva community” as if it is independent from him. The facts do not bear this out.

- 46(which appears to have no internet presence; the various other Buckingham Wealth companies found by a Google search have no connection to Baxendale-Walker)

- 47The judgment in Northwood v HMRC [2023] UKFTT 351 (TC) includes the text of an engagement letter between Baxendale Walker LLP and a client, which includes an appendix saying that “MINERVA” is a separate business of Baxendale-Walker LLP, which sells and markets strategies devised by Baxendale-Walker LLP. MINERVA’s fees were 10% for every contribution to the trust. PBW therefore most certainly knew what fees Minerva was making and, on the basis of the text from his own engagement letter, he benefited from those fees.

- 48The judgment in Dukeries Healthcare Limited [2021] EWHC 2086 (Ch) describes “Minerva” as an “associated company” of Baxendale-Walker LLP. Again, the Baxendale-Walker LLP engagement letter provided for a fee equal to 10% of each trust contribution to be paid to Minerva.

- 49As part of US litigation unrelated to the matters discussed in this report, a deed was disclosed under which Baxendale-Walker LLP says it holds sums as bare trustee for Minerva Services Limited

- 50The judgment in CIA Insurance Services v Commissioners for HMRC also refers to a Baxendale-Walker LLP engagement letter where 10% of each trust contribution was to be paid to Minerva.

- 51The judgment in Iain Paul Barker v Paul Baxendale-Walker notes that “As to [PBW’s] claim about lack of resources the Court was struck by three companies willing to financially assist Mr Baxendale-Walker, including his own remuneration trust, EW LLP, Minerva Ltd, Hawk, Brunswick Wealth and Burleigh House PTC Ltd.”

- 52The judgment in Paul Baxendale-Walker v APL Management Limited [2018] EWHC 543 states that, in May 2015, Baxendale Walker issued a claim “in respect of various fees that he alleged were owed to his companies (Baxendale Walker LLP and Minerva Services Ltd)” (my emphasis). That same case reports Minerva Services Limited (BVI), Minerva Services Limited (Belize) and Buckingham Wealth Ltd acting on behalf of PBW.

- 53There has been other litigation involving Minerva, the background to which is not clear to us, involving a Pankim Kumar Patel suing Minerva Services (Delaware) Inc, PBW himself and one other individual. The judgment is here. A witness statement is here, giving more of the background and with much criticism of PBW (although of course, as a witness statement, it must be taken with a pinch of salt).

- 54

23 responses to “HMRC errors let the UK’s most notorious tax avoider escape a £14m penalty”

I see this report gets a mention at para 5.7 of the TaxWatch report of 10 October 2024 “State of Tax Administration 2024” under the heading “HMRC Bloopers”.

Thank you Dan, I admire your work and applaud you commitment.

Apologies for delay but have been away on holiday without access to Wifi.

Most readers would find what you have described unbelievable.

P B-W deserves his comeuppance.

As do some in HMRC!

Having worked in the Inland Revenue [when there were in my view far more competent officers, though when I left I recall a very senior Inspector in a PI district saying ‘the problem now is that ‘only the ba….rds who are getting to the top’ !] and subsequently a large firm of Accountants HMRC incompetence no longer surprises me.

It is about time that something is done to rectify the current state of affairs.

This was an amazing read! Of course the rich get to avoid tax compliance in UK.

Boris Becker failed to fully declare assets when he went bankrupt, and ended up in jail.

What is different about PBW?

I was a Tax Partner for the no longer existing fifth of the Big 4 and we went to see Rangers in 2001 to talk about remuneration trusts. We’d done some work for non-dom bankers and thought we could do something clever for non-dom players for Champions League away matches, and a few other things.

We took the finest savings our best rocket scientists had devised and were shown the door inside half an hour because they had ‘something much better’.

If their alarm bell didn’t ring when I said ours was as far as you could go within the letter and spirit of the law as it was at that time (pre-GAAR), then, the club’s actions were their own fault too. I did laugh when I saw them go into liquidation and get relegated.

I think the main worry is for Morr &Co. Are they sure of being able to recover their fees, given their client’s history of impercuniousness as regards legal fees.

they re acting for PBW and related companies on a variety of matters. Unless they are crazy, they get paid up-front.

The legal world is too pedantic. Let some kid try explaining they didn’t submit £14m worth of homework because the teacher got a date wrong! If we don’t let our kids wriggle out of washing up, we shouldn’t let our crooks wriggle out of £14m tax bills, even if the paperwork is a bit of a shambles. Judges, give everyone a kick, get the money! Stop messing around.

Not all heroes wear capes.

Two small points:

1. There’s a typo in “if instead this is a a very specific denial”.

2. I know I’m fighting a losing battle on this, but that’s not what “begs the question” means.

As a layperson a couple of things stand out. First great work Dan exposing yet another high rolling charlatan. Next clearly HMRC like other public services are suffering severely from austerity and corporate resilience loss and lastly based on Baxendale- Walker’s delusional responses in face of all the counter evidence it’s time he applied to lead the Conservative Party.

I particularly liked point 31 in your response where you offer a unilateral contract that they have to pay you £1bn in order to reply. That’s if they believe their own version of the law. So hoist by their own petard.

Top Man Dan. I admire your persistence in pursuit of justice. I read the footnotes in case you had hidden the promise of a nice bottle of wine but not so! Is HMRC very badly resourced?

I did hide some fun additional detail, though…

in truth we don’t know what went wrong here, but some mixture of under-resourced, under-trained and under-experienced feels likely

Yes! I appreciate the commentary and fun facts that only you would know. It’s also incredible that so much of what you described is already in the public domain, however you have pieced it together beautifully, and identified exactly where HMRC went wrong. I hope you are appropriately credited when this gets reported in MSM.

How does this alleged £1bn in avoided taxes compare with that of HMRC’s alleged interest in Lord Bamford of JCB, which might also be a very interesting read? At first sight, it seems HMRC is failing in its responsibility to apply the relevant laws impartially to all taxpayers and begs the question why.

PBW’s book ‘Law & Taxation of Remuneration Trusts’ was published by Key Haven Publications Ltd, a company of which Robert Venables happens to be a PSC

yes, Venables provided at least one opinion for PBW. It was quite a doozy. http://www2.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2011/998.html#:~:text=Opinion%20dated%2029%20September%202003%20from%20Mr%20Robert%20Venables%20QC

Well done Dan. This is really important work shining a light on an individual who has caused misery for thousands and cost the public purse many, many millions. It also shows the problems HMRC causes itself through its overly complex law and process; as well as a failure to be on the front foot with such promoters.

Another excellent article. Given the current focus on politics, Dan has provided much needed scrutiny of the effectiveness of HMRC. If they can’t substantially improve their performance, our politicians will never manage to pay for their ambitious promises.

Currently, HMRC seem to prefer the “Post Office” approach to executing their role – failure to act timeously, followed by cover-up, combined with a preference for redact, deny, obfuscate, and persecute the “skint little people” in the immortal words of Sir Alan Bates. The outcome may not be quite as much of a scandal, but it should be.

So your special damages in libel arise when someone declines a unilateral contract by conduct or by any other means?

Gonna try that one. Why stop at £500K? No ambition these people.

If you publish this post, I want all the Jaffa Cakes.

It’s a good job you don’t have to pay £600 per footnote Dan.

PBW must have enjoyed this sentence: “I was never subject to any amended or discovery assessment for tax in this jurisdiction in relation to the tax properly paid on my drawings from Baxendale Walker LLP.”

As partners are taxed on their share of the firm’s profits, a lesser person might have said “No elephant asked me to paint an invisible squirrel.”

I have huge admiration for your persistence in matters like this, and for your readiness to stand up to bullying tactics.

I also love the way you publish in excruciating detail, thereby inviting a challenge you know full well will not come.

Thank you Dan and colleagues for a great public service.