As has been widely reported, Peter Mandelson forwarded confidential Government documents to Jeffrey Epstein, and advised the CEO of JPMorgan to “mildly threaten” the Chancellor of the Exchequer. This article considers the prospect of prosecuting Mr Mandelson for these acts.

Our view, on the basis of discussions with barristers and solicitors specialising in criminal and regulatory law is that:

- There is a realistic prospect that Mr Mandelson could be convicted for misconduct in public office. However, the archaic nature of the offence means that there is material uncertainty. In particular, it would be necessary to prove that Mr Mandelson either knew his actions were wrong, or that he was reckless as to whether they were wrong.

- There is also a realistic prospect that Mr Mandelson could be convicted for fraud by false representation, if (as Mr Starmer says) he lied in the process that led to his appointment as US Ambassador. It would be necessary to prove that Mr Mandelson dishonestly made a false statement, intending to make a gain (the salary from the role).

- The various other criminal offences that have been discussed (such as insider dealing and the Official Secrets Act) are unlikely to apply.1

- The Financial Conduct Authority should consider whether civil penalties could be applied to Mr Mandelson under the “market abuse” legislation – this is highly fact-dependent.

We assume throughout that the documents published by ourselves and others are authentic, and that the emails in those documents which appear to be sent by Mr Mandelson were in fact sent by him. We have no reason to doubt this is the case (and Mr Mandelson has not denied his authorship of the emails).

The views expressed in this article reflect the evidence of Mr Mandelson’s dealings with Mr Epstein that is in the public domain as at 7 February 2026. If further evidence comes to light (for example, further emails) then our views may change.

Nothing in this article constitutes legal advice.

In this report:

- Mr Mandelson's actions

- Evidence of dishonesty

- 1. Fraud by false representation[mfn]This section was not included in the original version of this article; that omission was kindly pointed out by commentators on social media.[/mfn]

- 2. Misconduct in public office

- 3. Insider dealing – the criminal offence

- 4. Insider dealing – civil offence

- 5. The Official Secrets Act

- 6. The Bribery Act

- 7. The Treason Act

- Can the emails be used as evidence?

Mr Mandelson’s actions

For the purposes of this note, we are putting Mr Mandelson’s actions into nine categories:2

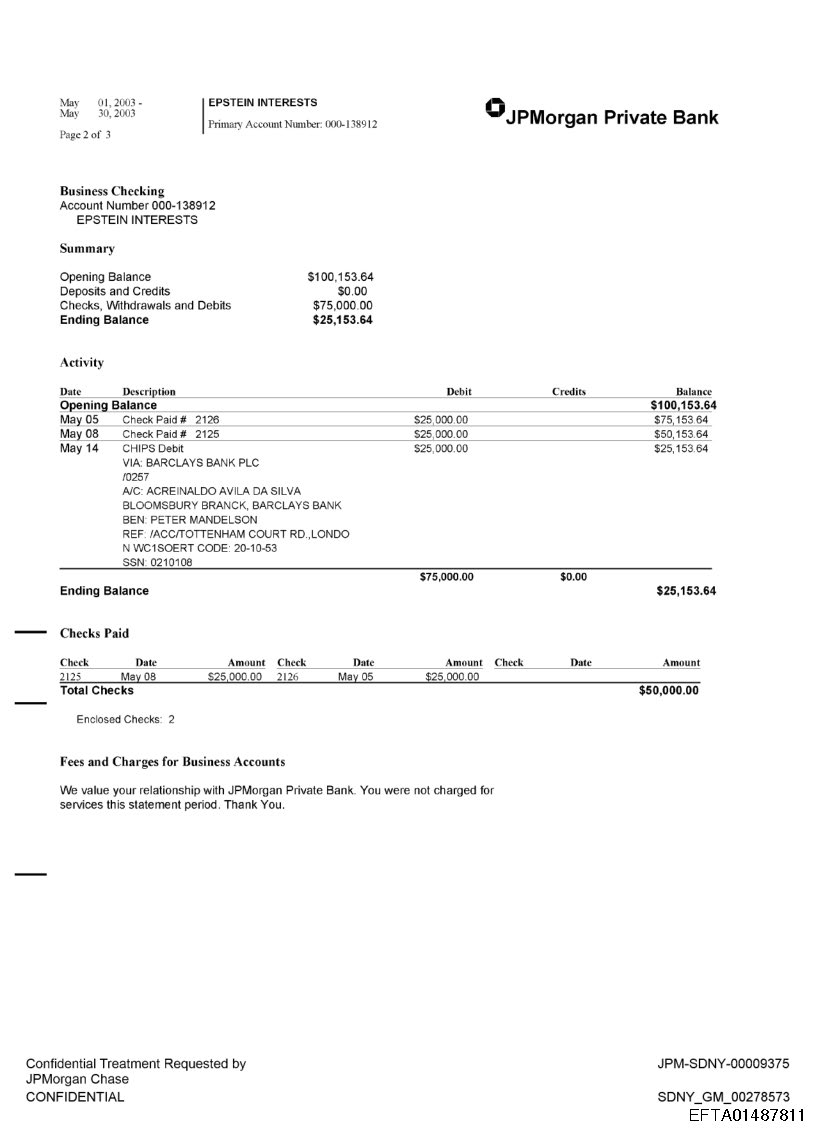

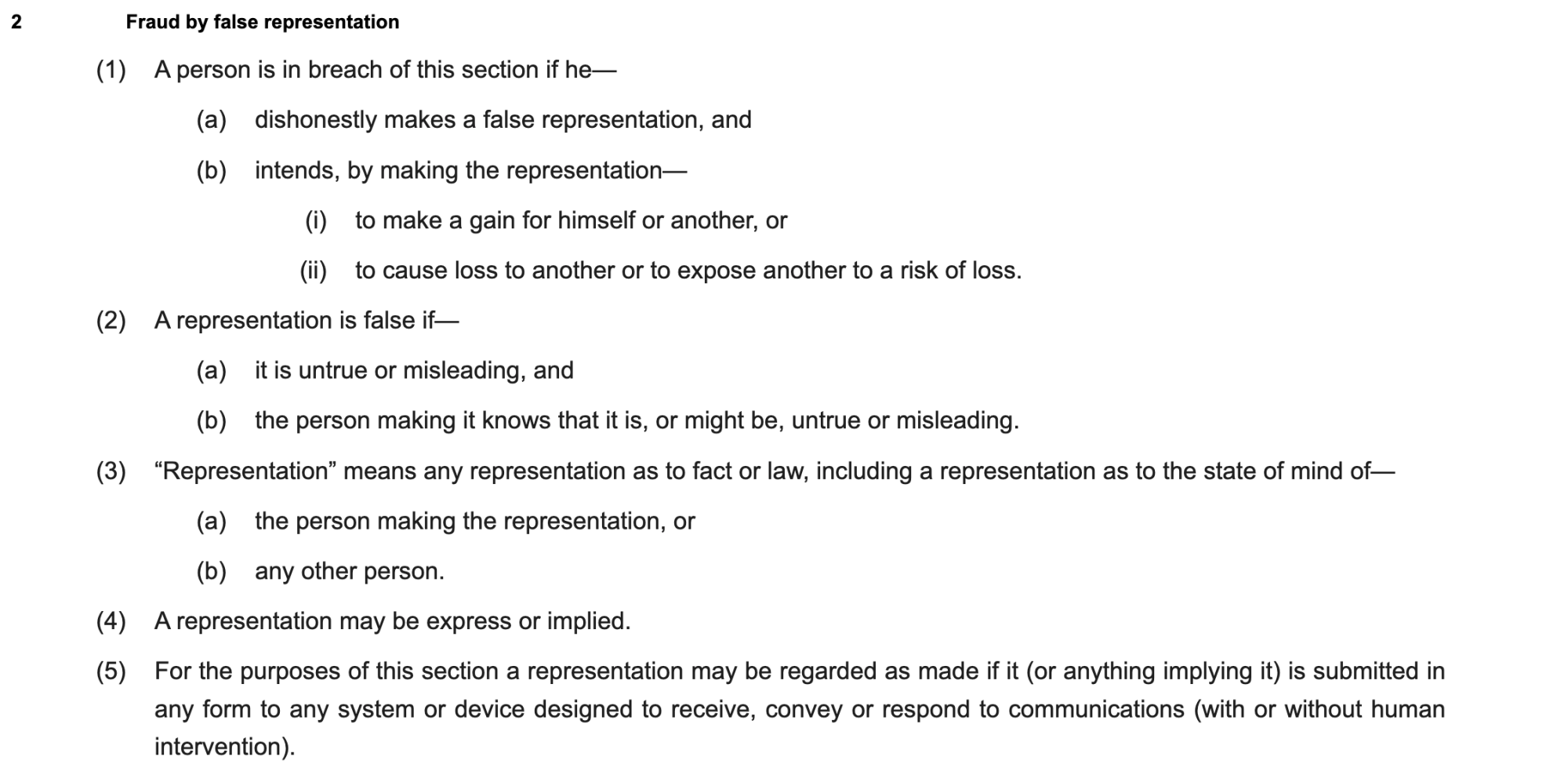

- Personal emails: Mr Mandelson and Mr Epstein exchanged thousands of emails, the contents of which were mostly innocuous and personal (see here for an example).

- Forwarding Government media notes: on many occasions, Government media personnel sent Mr Mandelson snippets from newspaper articles and other publications, which he forwarded to Mr Epstein (see here for an example).

- Leaking of a draft strategy note: On 20 December 2009, Mr Mandelson sent Mr Epstein a draft of a strategy note he had composed for Gordon Brown; Mr Epstein subsequently suggested changes to it.

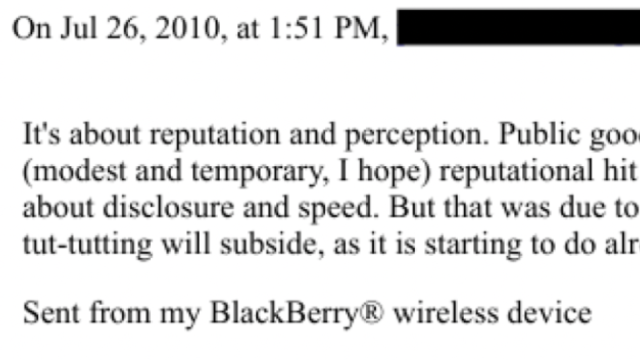

- Assisting lobbying against bank bonus tax: From 15 December to 17 December 2009, Mr Mandelson assisted Epstein’s efforts to help JPM lobby against the Government’s proposed new bank bonus tax. This culminated in Mr Mandelson advising Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPM, to “mildly threaten” the Chancellor (which it seems he did).

- Leaks of confidential Government information: In this category we would put the 13 June 2009 Nick Butler “saleable assets” email, the 2 August 2009 Vadera/Heywood email on financial markets and bank lending, the 9 May 2010 email tipping off Epstein that the Eurozone bailout was about to be concluded, and the 10 May 2010 email telling Epstein that Gordon Brown had resigned.

- Assisting JPM’s lobbying of Larry Summers and leaking confidential US Government information. In late March 2010, Larry Summers was in London meeting with Government figures including the Chancellor and Mandelson. Mandelson acted as a conduit for Epstein and JPMorgan, arranging a meeting for them, and forwarding informal and formal notes of meetings between Summers and the Chancellor, and Summers and Mandelson himself.

- $75,000 of gifts in 2003 and 2004. It is reasonably clear that Mr Mandelson received $75,000 from Epstein in 2003 and 2004 – we don’t know why, or have any emails or other documentation explaining the context, but the bank statements are reasonably clear, and Mr Mandelson issued what we would characterise as a very carefully worded non-denial.

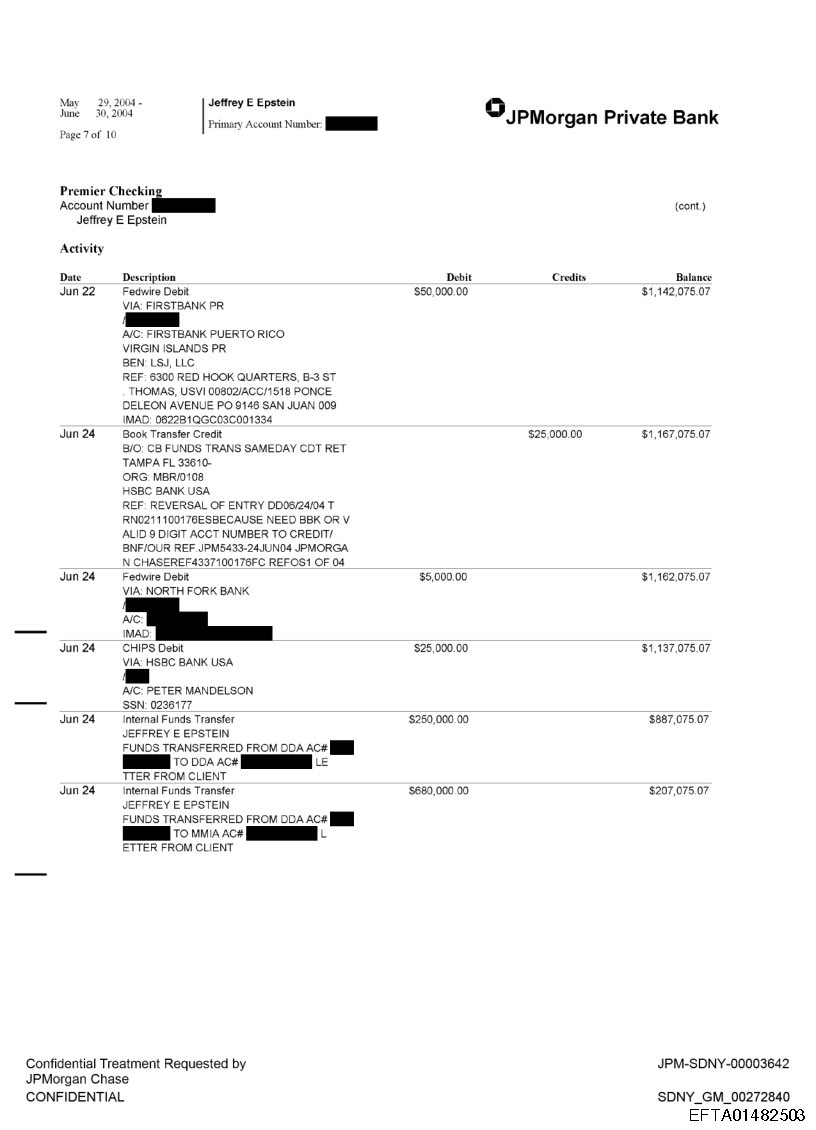

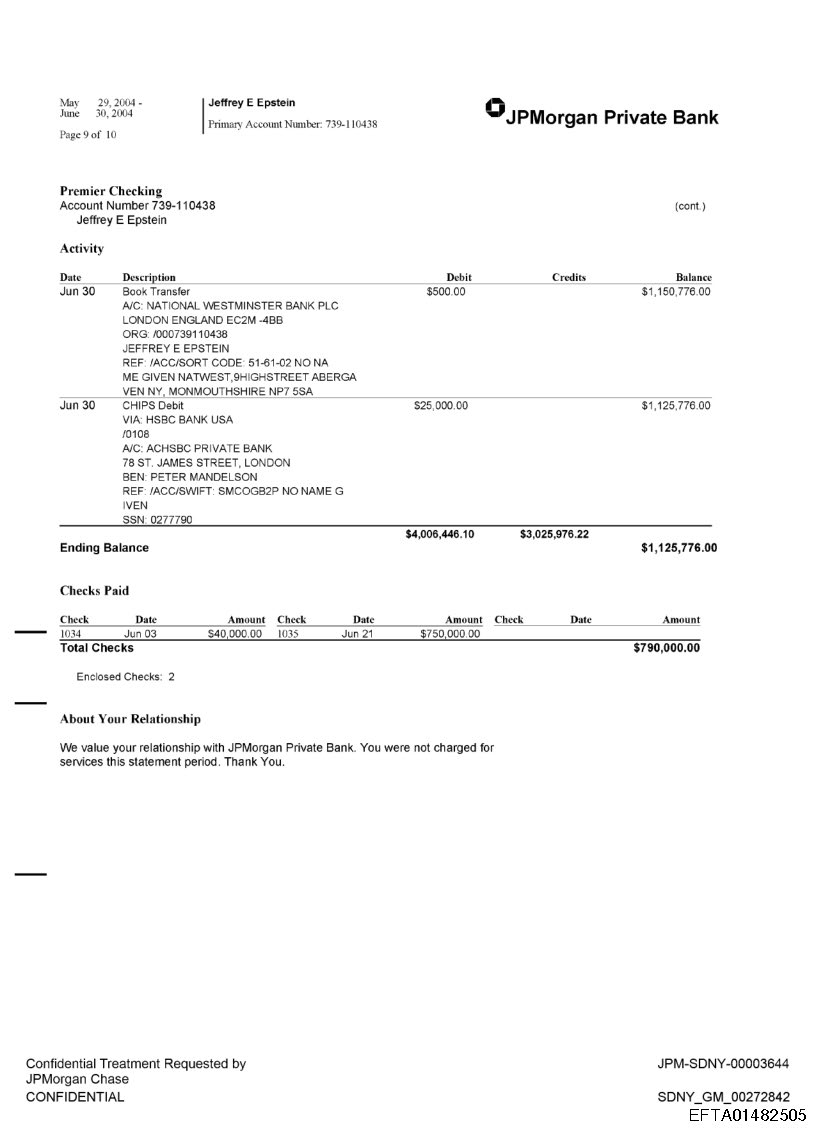

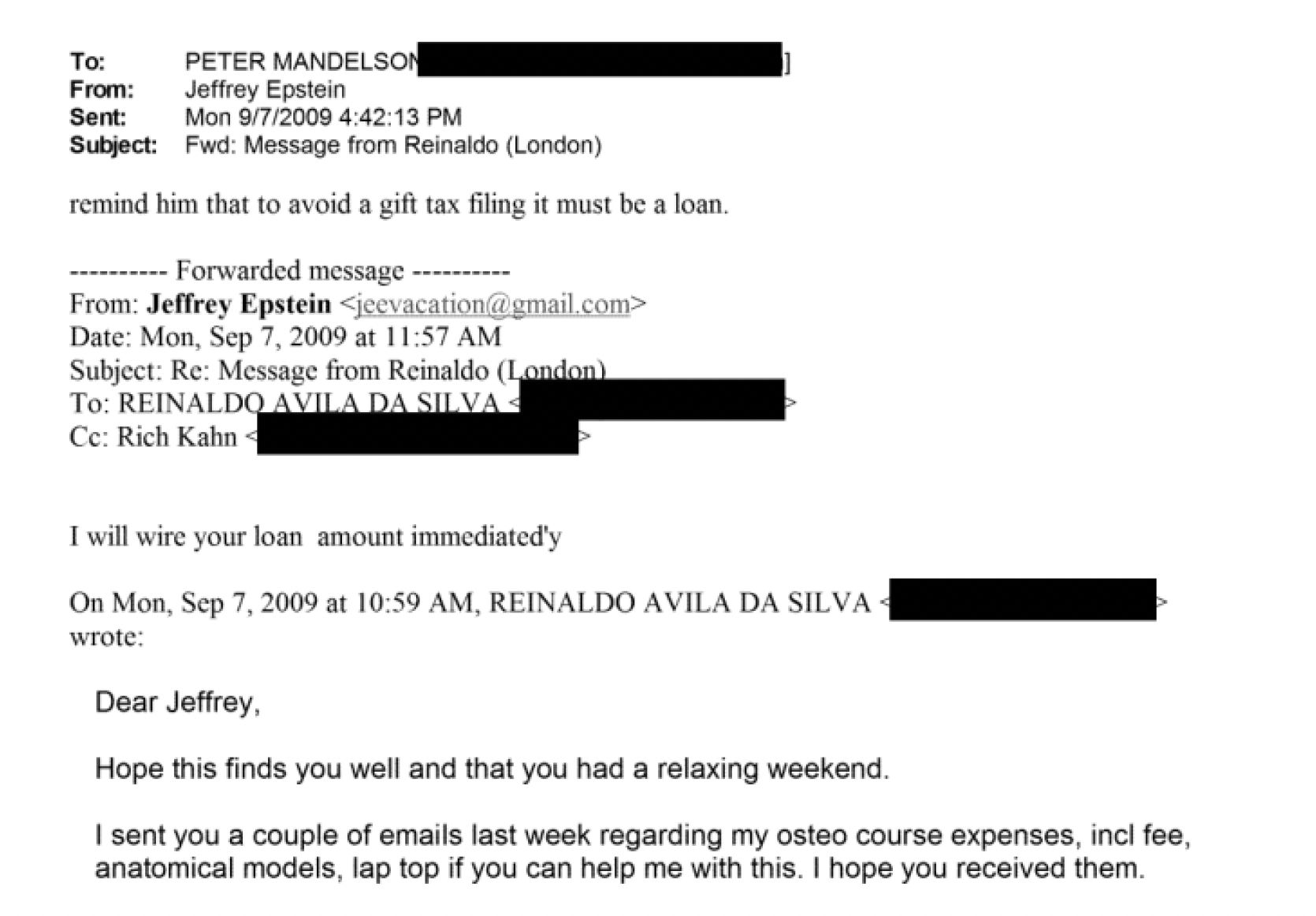

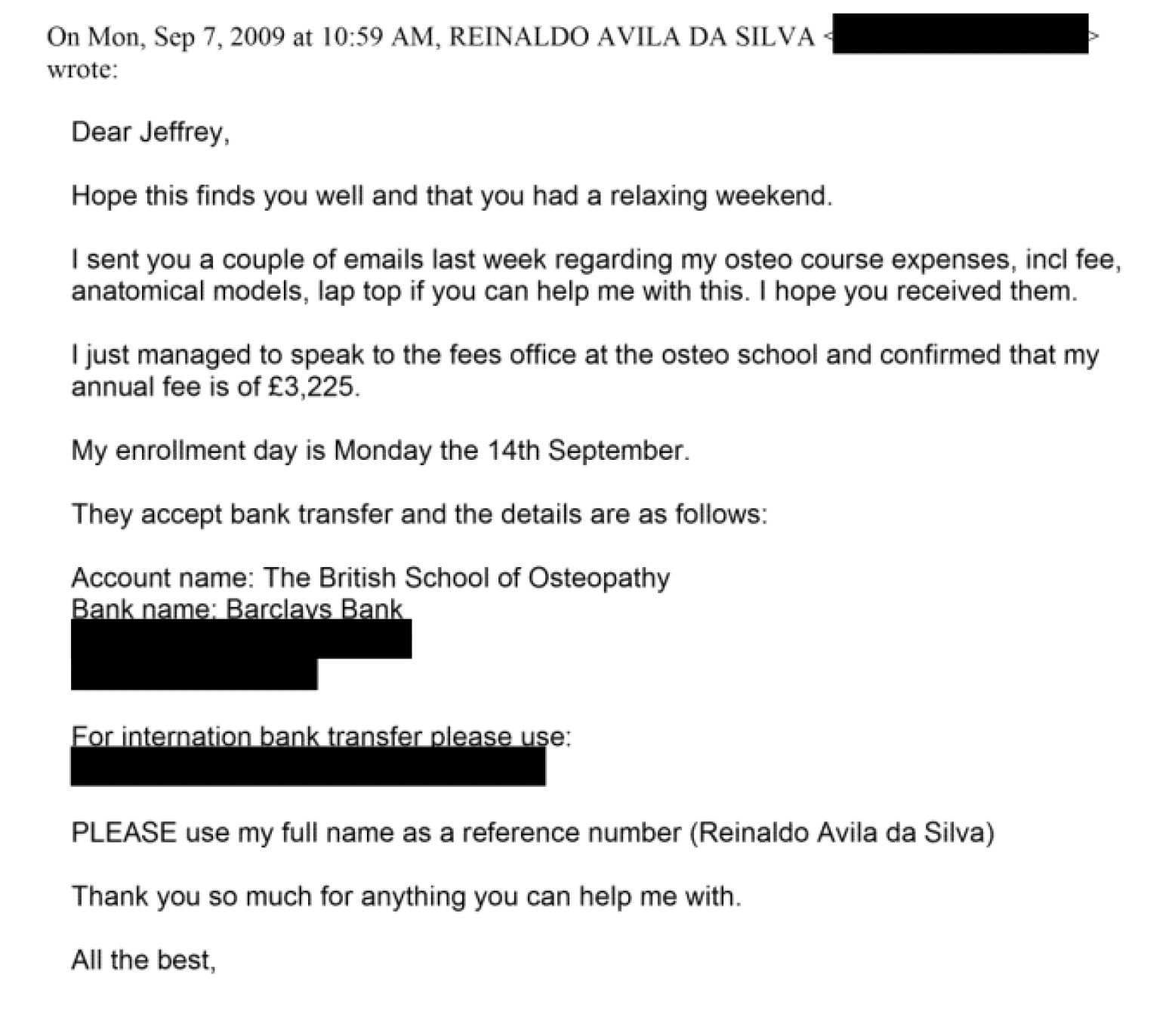

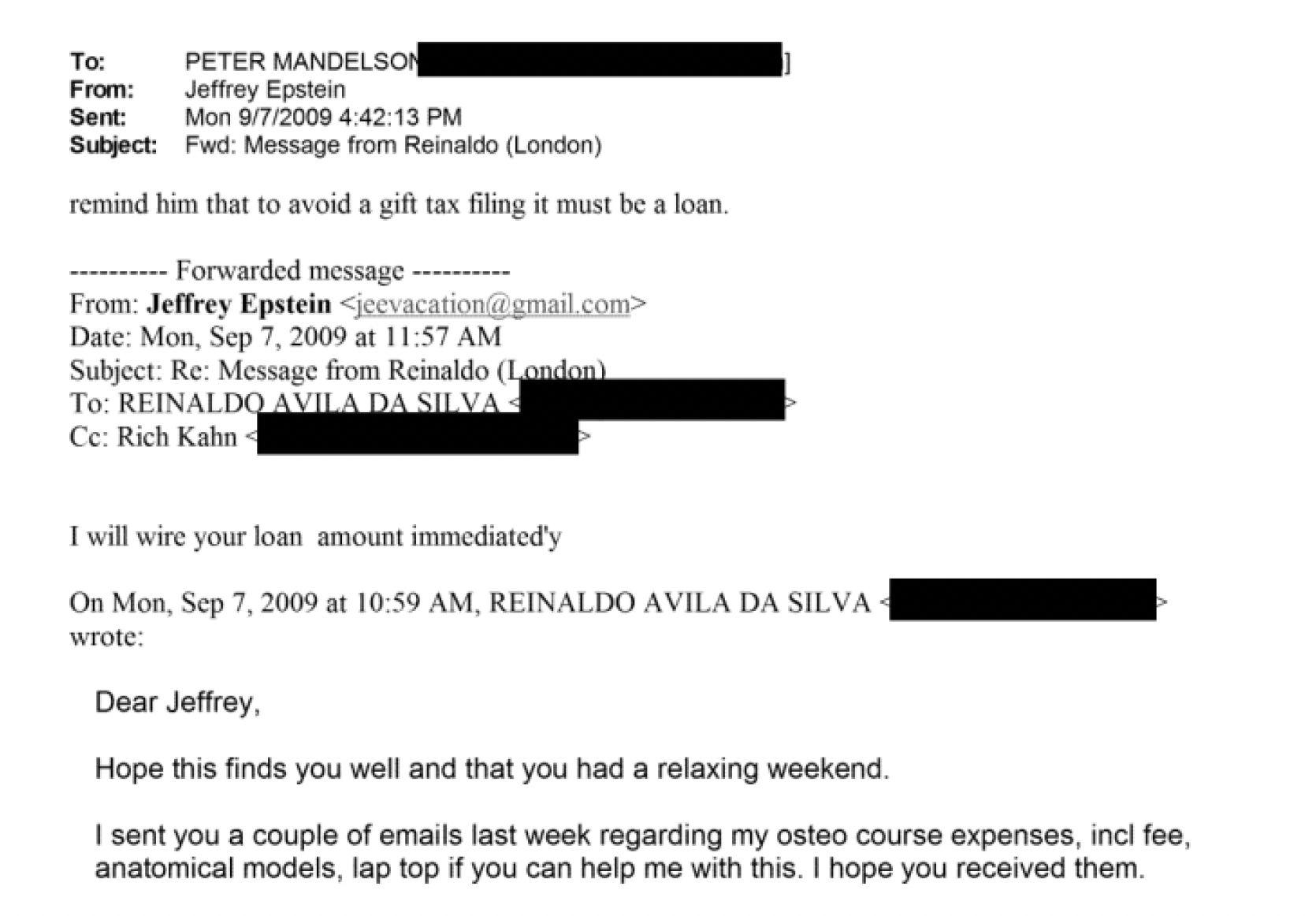

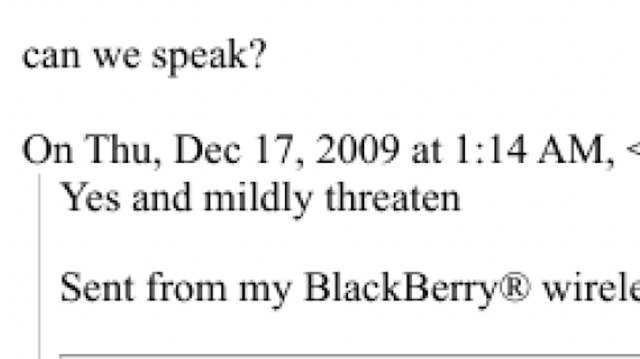

- An unknown amount of gifts in 2009 and 2010. In 2009, Mr Epstein agreed to make payments to Mr Mandelson’s then-partner to cover tuition fees for an osteopathy course. Epstein asked for the arrangements to be characterised as loans (so he could avoid US gift tax). The total amount is unknown, but is likely in the tens of thousands of pounds. Mr Mandelson responded to reports by claiming he thought the payments were bursaries from Mr Epstein’s charitable foundation – however the contemporary evidence suggests this is untrue, and he actually understood them to be gifts.

- Finally, either insufficient disclosure or dishonesty when being considered for the role of US Ambassador. Keir Starmer said Peter Mandelson “lied” to him, “repeatedly“, and apologised for believing Mandelson’s “lies” when he was directly asked about his relationship with Epstein. Mr Starmer said “none of us knew the depth of, the darkness of that relationship“.

This chart shows the approximate count of Epstein emails per month that are with, or refer to, Peter Mandelson:3

You can explore the Mandelson emails in the Epstein files in more detail with our public search tool, which includes an interactive bar chart where you can explore emails on particular dates.

Evidence of dishonesty

There is evidence of dishonesty in Mr Mandelson’s recent responses to reports that he received gifts from Jeffrey Epstein.

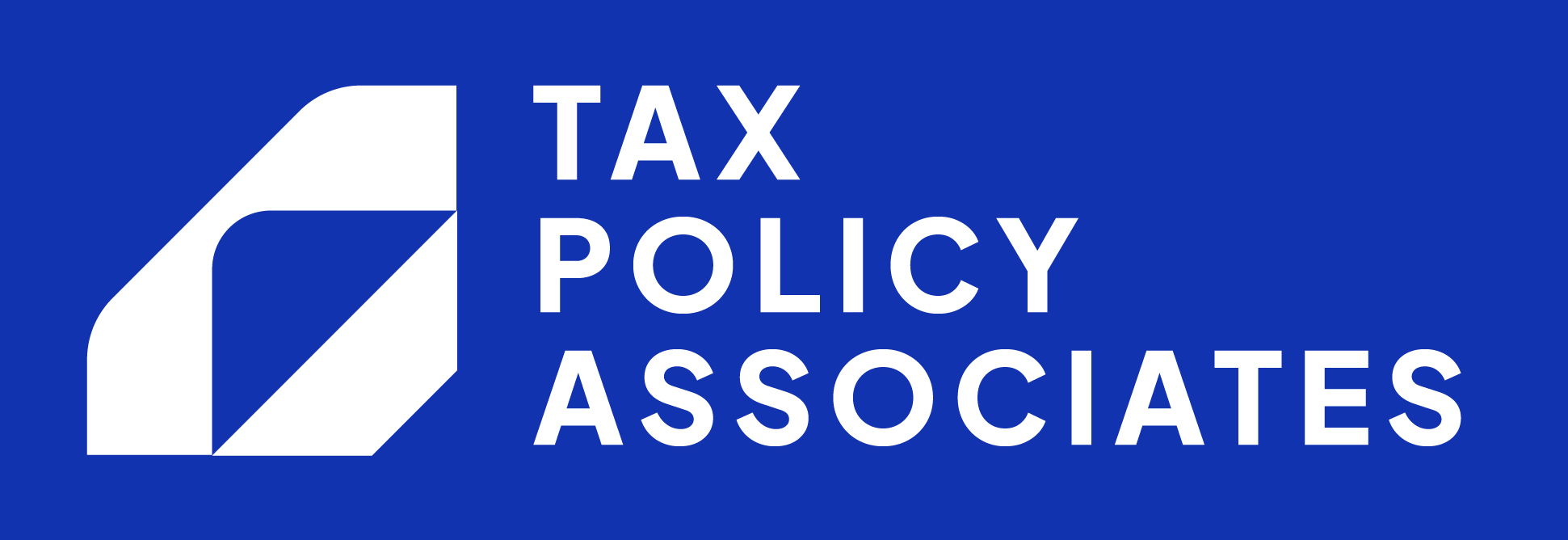

The Epstein files contain three bank statements, from 2003 and 2004, showing three transfers of $25,000 to Peter Mandelson:

Mandelson responded to this by saying:

“Allegations which I believe to be false that he made financial payments to me 20 years ago, and of which I have no record or recollection, need investigating by me.”

We showed the documents to two individuals4 who worked for JPMorgan Private Bank in the early 2000s, and they told us that the documents appear to be authentic JPMorgan Private Bank bank statements. We expect a police investigation would be able to confirm this by obtaining records from the UK banks that received these payments. If the payments were in fact received then in our view Mr Mandelson’s (carefully worded) denial is not credible.

The Epstein files also contain multiple emails demonstrating that a series of payments were made to Mr Mandelson’s then-partner in 2009 and 2010, ostensibly to fund tuition fees for an osteopathy course (which was never completed).

Mr Mandelson responded to reports of these payments by telling The Times:

“Epstein told Reinaldo that he had an educational foundation which gave bursaries or scholarships and offered one for an osteopathy course. I saw this as kindness, nothing more. It was a great help to Reinaldo and I thanked him.

“n retrospect, it was clearly a lapse in our collective judgment for Reinaldo to accept this offer. At the time it was not a consequential decision/”

However there is no evidence to support this in the Epstein files. The offer to help came from Jeffrey Epstein alone, and all the discussions at the time were personal. There was no mention at any point of a foundation or a bursary.5 Mr Mandelson’s partner sent payment details to Epstein personally, and all discussions about amounts and mechanics were directly with Epstein. We expect Mr Mandelson would know that this is not how foundations operate (even small ones).

Epstein insisted (first to Mr Mandelson’s partner and then to Mr Mandelson) that the arrangement had to be documented as a loan to avoid US gift tax. We expect Mr Mandelson would know that no foundation would act in this way; bursaries are tax exempt.

We expect a prosecution would say this the apparent dishonesty of Mr Mandelson’s responses is relevant to Mr Mandelson’s state of mind at the time of the events in question. If Mr Mandelson truly believed he had done nothing wrong, he would not be trying to “cover-up” the gifts.

1. Fraud by false representation6

This focuses on the simple question of whether Mr Mandelson lied in the appointment process for his ambassadorship. It would be the most straightforward offence to charge, technically and (probably) practically.

Section 2 of the Fraud Act 2006 says:

Looking at the conditions in turn:

- A false representation. It is a question of fact whether Keir Starmer (or others in his team) asked Mr Mandelson about his relationship with Epstein, and whether Mr Mandelson gave a false response. Mr Starmer has said that Mr Mandelson was asked, and gave a false reply. Mr Mandelson has responded that he answered questions about his relationship with Epstein in the vetting process accurately. 7 Mr Starmer has suggested there is written evidence of this – if that’s correct then a conviction may be reasonably straightforward. If not, the question will be whether a jury believes Mr Starmer’s version of events “beyond reasonable doubt” (something that would be greatly assisted if there are additional witnesses supporting Mr Starmer’s view of events).

- Dishonest. Mr Mandelson might say he misunderstood the question, or couldn’t remember the depth of his friendship with Mr Epstein. He might say his sole motivation was to avoid personal embarrassment. However if it is established that a false representation was made, we expect a prosecution would say that the gravity of events makes these explanations implausible. The judge would instruct the jury to apply the modern test of dishonesty: to first ascertain what the defendant actually knew or believed (subjective), and then decide if their conduct was honest by the standards of ordinary decent people (objective).

- With the intention of making a gain. That seems relatively straightforward; if appointed as ambassador then he would expect to receive a respectable salary plus significant other benefits and perks. Mr Mandelson might again argue his sole motivation was to avoid personal embarrassment and not to secure the job. He could go further and say that, even if he intended to secure the job, the salary was (for him) so modest that it was not a motivation. We are unsure either defence could be put to a jury in that form. Even if obtaining the salary was not a primary objective, or even a material objective for him, it was an inevitable outcome of the appointment which, in turn, Mr Mandelson must have appreciated was the likely outcome of not disclosing his deep friendship with Epstein. Therefore our view is that Mr Mandelson could probably be said to have intended the gain.

We expect that a prosecution would seek to adduce the evidence discussed above that Mr Mandelson lied publicly about the gifts he received from Epstein. They would say this is evidence of a propensity to lie when Epstein-related facts are inconvenient. Evidence of “bad character” is not admissible unless the prosecution can show (amongst other things) it is important explanatory evidence.

Lying on a CV to obtain a job is a fairly straightforward application of section 2, and attempts to say that “everybody exaggerates on their CV” have not been successful. The maximum sentence is ten years’ imprisonment; there is also the prospect of a confiscation order for the earnings obtained by the false representation.

There is an additional offence in section 3 of the Fraud Act of fraud by failing to disclose information; however it only applies where a person is under a legal duty to disclose, and we are not aware of such a duty (although it’s possible the appointment process has legal elements of which we are unaware).

2. Misconduct in public office

Misconduct in public office8 is not found anywhere in the statute book – it’s a common law offence, created by judges over centuries9 (with its modern form dating from 1783). The offence was rarely prosecuted in the post-war period, but more recently has been increasingly used, often against prison officers who have had improper relationships with prisoners.

The archaic and uncertain nature of the offence has been criticised by the Law Commission and others, and the offence may be abolished and replaced in this parliamentary session (but of course not with retrospective effect).

The Court of Appeal summarised the components of the offence as:

- A public officer acting as such.

- Wilfully neglects to perform his duty and/or wilfully misconducts himself.

- To such a degree as to amount to an abuse of the public’s trust in the office holder.

- Without reasonable excuse or justification.

The question is, therefore, whether forwarding Government emails to Mr Epstein, providing Mr Epstein with a summary of meetings, and advising Jamie Dimon to “mildly threaten” the Chancellor, satisfies these conditions.

We will consider each in turn.

A public officer acting as such

It is clear that a Minister is a “public officer”.10

A more difficult question is “acting as such”. The defendant must be acting in the discharge/exercise of their public functions, not merely misconducting themselves whilst holding office. As the CPS guidance says, on the basis of the case law, there must be a close nexus between the wilful neglect/breach of duty or wilful misconduct and the power, authority, responsibilities and/or duties vested in the suspect by virtue of their office. That is why the Boris Johnson private prosecution failed: the High Court held that statements made during a political campaign were not acts done “in the discharge of his duties” as Mayor and MP.

Looking at our categories of behaviour by Mr Mandelson:

- Personal emails: Many people would say that it was improper for a Government Minister to exchange emails with a convicted sex offender, however we believe these emails fell outside the discharge of Mr Mandelson’s public duties, regardless of whether Mr Mandelson was in a Government building at the time, and/or sending the emails using a Government-issued device. The law does not require a formalistic determination of whether a person is physically “on duty“, but whether they are (in substance) acting as part of the exercise of their public functions. Here we would say Mr Mandelson was not.

- Forwarding Government media notes: When Mr Mandelson received Government emails and forwarded them to Mr Epstein, we believe he was acting in the course of his public duty. If he wasn’t a Minister then he would not have received the emails. The “act” under scrutiny is not an unrelated private act but the handling (and onward disclosure) of official information encountered through office. The fact the media notes contained no confidential information does not change the answer (but is relevant to the “misconduct” limb considered below).

- Leaking of a draft strategy note: Our view is that the strategy note was a political document and not a Government document. When Mr Mandelson forwarded the draft to Mr Epstein, he was acting in the course of his political role, but not in the course of his public duty as a Minister. Opinions may differ, and this point is certainly not beyond doubt.

- Assisting lobbying against bank bonus tax: Mr Mandelson was using his own discussions with the Chancellor to lobby on behalf of Mr Epstein and Mr Staley, and then advising JPMorgan (through Mr Epstein) how to lobby directly. Liaising with business and representing its views to other Ministers is part of the role of the Business Secretary. Whether Mr Mandelson behaved properly is a separate question we will look at below, but the nature of the act means in our view he was acting as a public officer and not a private citizen.

- Leaks of confidential Government information: Mr Mandelson was acting in the course of his public duty when he received confidential Government emails for the same reason discussed above in the context of media notes.

- Assisting JPM’s lobbying of Larry Summers and leaking confidential US Government information. The lobbying activity was in the course of Mr Mandelson’s duty for the same reason as the bank bonus tax lobbying; the leaking was in the course of Mr Mandelson’s duty for the same reason as the media notes.

- 2003 and 2004 payments totally $75,000. The payments were received when Mr Mandelson was an MP, which is a “public office” for this purpose. However we currently do not know why the payments were made; we therefore have no basis for saying if they were received by Mr Mandelson in the course of acting in his public office.

- 2009 and 2010 payments to Mr Mandelson’s partner. These payments were received when Mr Mandelson was Business Secretary and a senior member of Cabinet. However, given that the payments were purely personal in nature, we don’t think they can be said to have been received in the course of Mr Mandelson’s public office.

- insufficient disclosure or dishonesty when being considered for the role of US Ambassador. We don’t believe lying (if that is what happened) in the course of applying for public office is within the scope of the offence.

It is therefore our view that Mr Mandelson was acting as a public officer for four out of the nine categories of behaviour this article considers. The exceptions – the exchanges of personal emails and the strategy note – will not be discussed further in this article.

Wilful breach of duty or misconduct

This has two elements. There must be a breach of duty (or misconduct) and it must be wilful.

The Court of Appeal has held that the word “wilful” means that the prosecution must prove more than a failure to meet an objective standard. The breach must be deliberate or subjectively reckless, not merely inadvertent, stupid, mistaken, or careless.

Looking at the four remaining categories, we will first consider whether there was a duty:

- Forwarding Government media notes: We don’t believe these notes contained any confidential information. So we are doubtful there was any duty on Mr Mandelson not to forward them. We will therefore not consider this category further.

- Assisting lobbying against bank bonus tax: There is clearly no duty not to lobby against your own Government – such behaviour is commonplace. Mr Mandelson’s actions went further than that – he misused ministerial position for an improper purpose. That duty arises from the nature of public office: powers and access are conferred for public purposes, and using them to advance a private interest (or to act as a conduit for a private party’s lobbying strategy) can constitute a breach of duty.11

- Leaks of confidential Government information: We believe it’s reasonably clear that a Minister has (i) a duty to safeguard confidential information obtained by virtue of office, and (ii) a duty not to misuse privileged access to internal policy/market-sensitive material for non-public purposes. That kind of duty is routinely treated as capable of underpinning misconduct in public office prosecutions in practice – see CPS guidance.

- Assisting JPM’s lobbying of Larry Summers and leaking confidential US Government information: For the lobbying/conduit aspect, the same duty framing as the bank bonus tax point applies. For the leaking aspect, the duty point is again more straightforward: unauthorised onward transmission of confidential meeting notes / “formal notes” received by virtue of office fits the paradigm of safeguarding official information.

Then, for the three remaining categories, the question is whether any breach can be considered wilful.

Mr Mandelson’s acts were obviously intentional – that is not in doubt. The live issue for “wilful” is Mr Mandelson’s state of mind when lobbying/forwarding. It’s not enough to say Mr Mandelson should have known better, and/or was reckless. The question is whether he (i) knowingly breached a duty (or at least appreciated a risk that he was breaching one), or (ii) acted with reckless indifference (“not caring”) to that question and/or to the relevant risks.

Recklessness in this context means subjective recklessness i.e., the suspect was aware of a risk and in the circumstances known to them at the time it was unreasonable to take that risk.

In other words:

- If Mr Mandelson genuinely believed – even mistakenly or stupidly – that (for example) sharing the Larry Summers meeting summaries with Epstein was part of his job or permitted, he cannot be guilty of this offence. As the Court of Appeal said, “a mistake, even a serious one, will not suffice”.

- However if Mr Mandelson suspected it might be wrong but avoided checking the rules because they didn’t want to know the answer (wilful blindness), that would constitute subjective recklessness.

We expect a prosecution would say that any Cabinet Minister knows it is wrong to advise a foreign bank to threaten the Chancellor, or to share internal Government emails and meeting notes with third parties, particularly a third party who Mr Mandelson knew had been convicted of a serious criminal offence.

We concluded that accepting gifts from Mr Epstein did not give rise to a wrongful conduct in public office itself, because we don’t believe the gifts can be said to have been received in the course of Mr Mandelson’s public duties. However the gifts are relevant to the factual question of whether Mr Mandelson knew he was wrong to lobby and share the emails, or whether he was reckless in doing so. As we discuss above, Mr Mandelson’s recent statements regarding the gifts are in our view not credible, and we expect a prosecution would say those statements are evidence that Mr Mandelson knew his relationship with Mr Epstein was wrong.

We foresee two potential responses to this from Mr Mandelson.

A possible response would be for Mr Mandelson to contend that he did not appreciate that Government emails or meeting notes of this kind were not meant to be shared with trusted third parties. The difficulty with that position is the selectivity of the disclosures. Only a relatively small subset of the material he received was forwarded, and it was material of a particular sensitivity and interest to the recipient. That pattern sits uneasily with an explanation based on general ignorance of the rules, and instead suggests a conscious judgment about what could and could not be shared. We expect a prosecution would also note the unusual choice of trusted recipient – a convicted sex offender. Ultimately, however, it would be a matter for the jury whether any claimed lack of awareness should be accepted.

Mr Mandelson might go further than professing ignorance. He could say something like: “I believed what I did was part of legitimate stakeholder engagement and was in the public interest”, particularly in relation to the discussions around the shape of US regulatory reform. This would be a more credible argument if Mr Mandelson forwarded Government emails to other finance figures, and not just Mr Epstein. We do not know if he did. But if Mr Epstein was the only recipient of such emails then it looks much more like a personal (and potentially corrupt) favour than as stakeholder engagement. A further difficulty with this argument is that stakeholder engagement (in our collective experience) never involves sharing internal Government meeting notes.

We again expect that a prosecution would seek to adduce the “bad character” evidence discussed above that Mr Mandelson lied publicly about the gifts he received from Epstein, and would say this is evidence of a propensity to lie when Epstein-related facts are inconvenient.

Abuse of the public trust

This has been held to involve “a high threshold, requiring an affront to the standing of the public office held, and conduct so far below acceptable standards as to amount to an abuse of the public’s trust in the office holder”.

Lord Justice Bean put it more memorably: “there is and should be no offence of ‘being so naughty that a jury thinks you should be sent to prison’”.

So whilst it has been suggested that the offence could be applied to Ministers taking up paid employment after leaving office, and using the benefit of their experience and contacts for that purpose, we think that is incorrect on the basis of the decided authorities. “Abuse of the public’s trust” is a high bar, and political and/or moral disapproval of a person’s actions does not reach it.

The abuse must be “serious“. For this reason, Keir Starmer, when Director of Public Prosecutions, decided not to prosecute a civil servant who had leaked confidential Home Office documents to a Conservative Party politician; Mr Starmer thought that the damage done by the leaks was insufficient to amount to a serious abuse of the public trust. Furthermore, the leaker’s stated purpose was political accountability; a jury might well see that as a proper purpose.

By contrast, the Court of Appeal held in R v Norman that a prison officer who had accepted payments of £10,000 from journalists over five years was conduct which the jury were entitled to conclude caused significant public harm, because it undermined public confidence in the prison service.12

We see the Mr Mandelson case as considerably more serious than R v Norman. We expect there would be a serious abuse of the public’s trust if a Cabinet Minister leaked Government documents to (say) Jamie Dimon. However when the recipient of the leaks is a convicted sex offender, the “seriousness” seems relatively easy to establish. We expect those in Government at the time would testify that they felt betrayed.

The abuse of trust in the Mandelson case is heightened by what is, at a minimum, a conflict of interest. Mr Mandelson was personally close to Mr Epstein, he and his partner received money from Mr Epstein, and ultimately Mr Epstein helped Mr Mandelson find lucrative employment and consultancy opportunities. There may have been no explicit quid pro quo, but we believe these facts are sufficient to put to a jury that Mr Mandelson had a conflict of interest.

We therefore expect that a jury is entitled to conclude that Mr Mandelson’s actions caused significant public harm; it damaged the integrity of Government decision-making, and undermined public confidence in politics and in government.

Without reasonable excuse or justification

We have already had a flavour of the defence Mr Mandelson might run. He defended his advice to JPMorgan to “mildly threaten” Alistair Darling by saying that his concerns about the bankers’ bonus tax reflected wider concern in the financial services industry:

Every UK and international bank was making the same argument about the impact on UK financial services… My conversations in government at the time reflected the views of the sector as a whole, not a single individual.

He could develop this further, and say that he believed he was acting in the UK’s best interests, because it was his view that proposed tax and regulatory changes were against those interests.

Whether that is credible would ultimately be something for a jury to decide. It is, however, our view that the contemporaneous evidence is not consistent with Mr Mandelson’s explanation – the correspondence with Mr Epstein does not refer to the UK’s interests, or show signs of considering the UK’s interests. It is one thing to seek to understand the views of the financial services sector, and advocate them in Government; quite another to advise a foreign bank to “mildly threaten” the Chancellor. Indeed the discussions with Mr Epstein don’t appear to consider the interests of the financial sector generally – they are focused around JPMorgan and its own commercial interests, via Mr Epstein’s close contact with Jes Staley:

It seems more plausible that Mr Mandelson’s motivations were linked to his wider relationship with Mr Epstein, which seems to have been in part a genuine friendship (at least on Mr Mandelson’s part) and in part driven by expectations of future employment on Wall Street.

There is a further, deeper, problem, to a defence framed as “I thought it was good policy to protect the financial sector”.

The fact that a particular end may be appropriate and even desirable does not make the means used to achieve that end automatically reasonable. If Mr Mandelson had been briefing a journalist then the means might be appropriate; in this case, showing the means were appropriate feels challenging.

Conclusion

Overall, we think a misconduct in public office prosecution would have a realistic prospect of conviction on the evidence presently available, principally because the alleged conduct involves selective disclosure of internal Government information to a private individual, alongside apparent use of ministerial access to facilitate private lobbying. The strongest points for the prosecution would be (i) the deliberate and selective nature of the leaks and interventions, (ii) the sensitivity of some of the information, and (iii) the potential conflicts of interest arising from Mr Mandelson’s relationship with Mr Epstein. The main uncertainties are inherent to the offence itself: the high and fact-sensitive threshold for “abuse of the public’s trust”, and the need to prove Mr Mandelson’s state of mind (whether he appreciated the impropriety, or was at least recklessly indifferent to it), rather than merely showing poor judgment. Those issues would ultimately turn on the surrounding evidence and the credibility of any explanation Mr Mandelson chose to give.

3. Insider dealing – the criminal offence

The insider dealing rules require more detailed consideration.

Mr Mandelson passed information to Mr Epstein which we would, in a commercial sense, describe as “market-sensitive”. This included the timing of Gordon Brown’s resignation, the €500bn Eurozone bailout, and early discussions around the shape of international financial services reform.

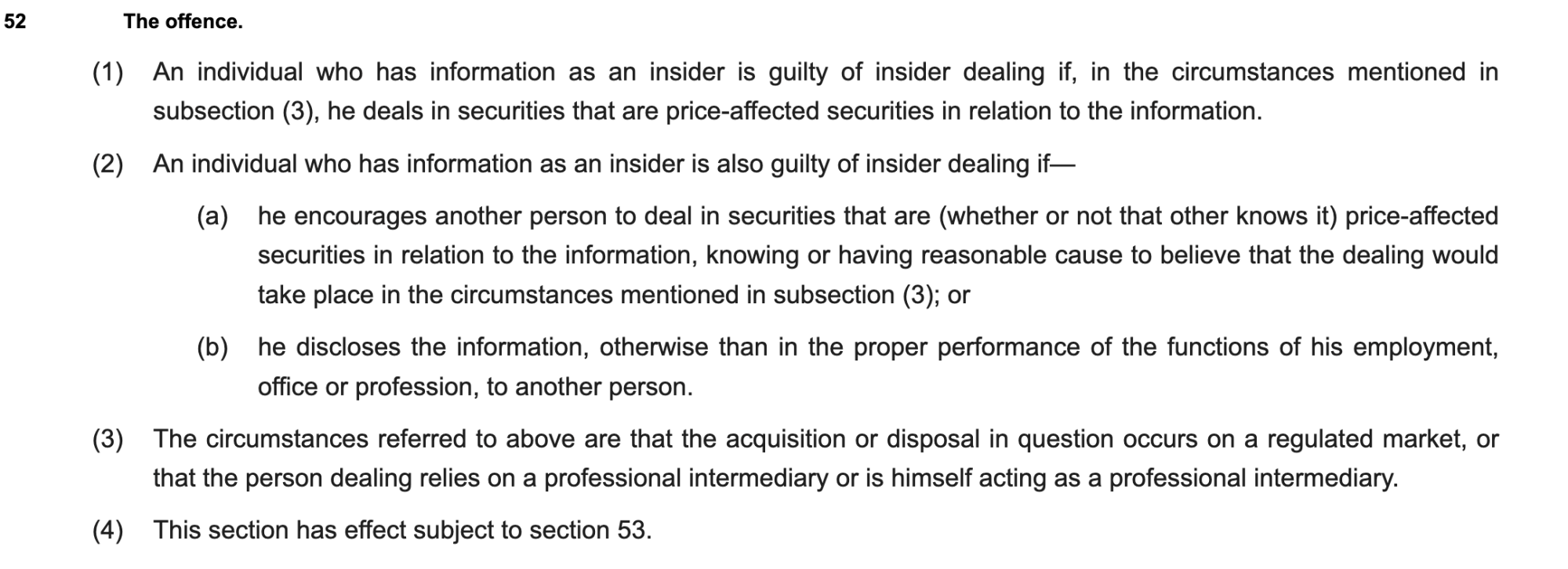

That potentially engages the insider dealing offences. In 2009 and 2010, these were contained in section 52 of the Criminal Justice Act 1993:13

At first sight it looks as if the “disclosure” offence in section 52(2)(b) may have been committed. However there are three serious barriers to a prosecution.

First, section 56 defines “inside information” to mean information relating to specific securities and issuers:

None of the information passed by Mr Mandelson related directly to specific securities. It might be argued that (for example) the information on the Eurozone bailout was particularly price sensitive for Eurozone government issuers, and they were therefore “particular issuers of securities”. That, however, feels insufficiently precise – particularly given the express exclusion for “issuers of securities generally”. We expect that “relates to” would be given a narrower meaning (although we are unaware of any authority on this point).

Second, section 56 requires that the information would, if made public, “be likely to have a significant effect on the price of any securities”. This is a question of fact, and one we have not investigated – however, City experts we have spoken to are doubtful that there would have been any significant effect, as the Eurozone bailout and Mr Brown’s resignation were both anticipated and therefore substantially “priced-in”.

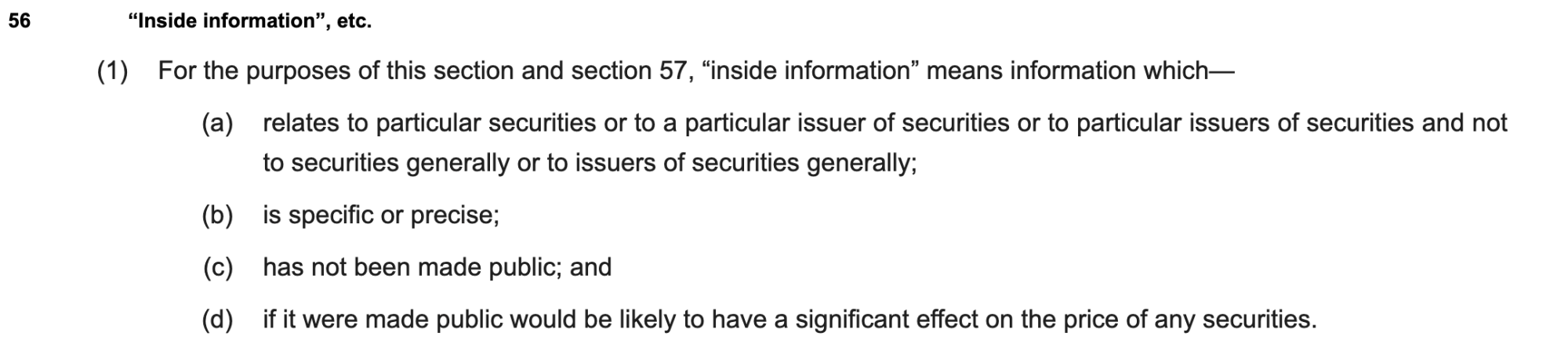

Third, and most seriously, there is an absolute defence to the disclosure offence in section 53:

We expect Mr Mandelson would say he did not expect any person to deal in securities on the back of his leaks. On the basis of the evidence we have reviewed, this would be credible – we have seen no sign that Mr Epstein or anybody else intended to deal. Our belief, based on an extensive review of the Epstein files, is that Mr Epstein used the information as a currency in itself, to gain favour and credibility with his extensive contacts on Wall Street.

This third reason is likely to be fatal to any prosecution for insider dealing.

4. Insider dealing – civil offence

There is also a prohibition on insider dealing in the market abuse rules in section 118 of the Financial Services and Markets Act (FSMA). This is not a criminal offence; the consequences of breach are limited to regulatory sanctions and civil penalties.14

There is again a question as to whether the information provided by Mr Mandelson was specific enough to fall within the ambit of the rules. The prohibition on disclosure in section 118 applies only to information “of a precise nature” which (broadly speaking) would be likely to have a significant effect on the price of securities.

For the same reasons noted above in the context of insider dealing, we think it’s doubtful that Mr Mandelson’s disclosures were “precise” enough for section 118 to apply, and also doubtful whether the information would have had a significant effect on the price.

If, however, we are wrong on these two points, then applying market abuse penalties would be significantly easier than an insider dealing prosecution. Unlike the CJA 1993, there is no “motive” defence, and penalties are applied on the basis of the civil standard of proof (the balance of probabilities) and not the criminal standard (beyond reasonable doubt).

Where penalties can be applied, they are unlimited – the legislation provides for penalties of such amount as the Financial Conduct Authority “considers appropriate”.

The market abuse position is therefore not at all straightforward, but in our view would justify an investigation by the Financial Conduct Authority.

5. The Official Secrets Act

The Official Secrets Act 1989 applies to Government Ministers. However in our view the available evidence suggests that none of the offences in the Act are applicable:

- Sections 1 and 2 of the Act apply only to information relating to security or intelligence or defence; none of the emails identified to have been leaked by Mr Mandelson to Mr Epstein fall in this category (and Mr Mandelson’s role means his access to such information would have been relatively limited).

- Section 3 applies to “damaging disclosures” of confidential information relating to, or obtained from, another State. The emails and meeting notes leaked by Mr Mandelson regarding discussions with Larry Summers are potentially within this provision. However, a disclosure is only “damaging” if it “endangers the interests of the United Kingdom abroad, seriously obstructs the promotion or protection by the United Kingdom of those interests or endangers the safety of British citizens abroad” (or is likely to do so). We don’t believe the evidence shows that the UK’s interests were endangered; Mr Mandelson’s actions merely gave commercial advantage to Mr Epstein and his contacts.15

- Section 4 applies to (amongst other things) disclosures that result in the commission of an offence. The word “offence” is not defined, but we believe it likely encompasses matters that are a criminal offence in other jurisdictions. It is therefore conceptually possible that section 4 applies; say if Mr Mandelson’s leaks of market-sensitive matters were used for trading purposes, and that resulted in a criminal offence being committed (in the US or elsewhere). There is, however, no evidence that any such trading took place, or indeed that any other offences were committed as a result of Mr Mandelson’s leaks to Mr Epstein.

6. The Bribery Act

The Bribery Act only came into force from 1 July 2011 – after most of the events to which it could (even potentially) be applied.

There was older anti-corruption legislation which the Bribery Act replaced. The Prevention of Corruption Act 1916 was principally relevant to certain contract/procurement contexts. The Prevention of Corruption Act 1906 was wider in scope, but had the evidentially challenging requirement to prove corrupt intention (the Bribery Act is much broader in scope).

There is a useful briefing on the pre-2011 provision from the House of Lords Library.

7. The Treason Act

We have spoken to people working in Government in 2009 and 2010 who describe Mr Mandelson’s actions as “treachery” or even “treason”. However as a legal matter, treason is a tightly defined offence, under a series of archaic statutes. None of Mr Mandelson’s actions are covered by these offences.

There have been no prosecutions for treason since 1946. The Law Commission has recommended modernising and simplifying the law, and the previous Government considered doing so, but in the event no changes were made.

Can the emails be used as evidence?

As of today, the only evidence we have of Mr Mandelson’s actions are the PDF copies of Epstein’s emails, available from the US Department of Justice’s public “Epstein Library“. We do not know how the emails were obtained, what device or devices they were obtained from, or what processes were used to extract the emails from those devices and generate the PDFs. The PDFs have been redacted (automatically) and have lost the underlying “metadata” that the original emails contained, showing the electronic path that the emails took.

If there was a prosecution, then it may be that Mr Mandelson would accept the authenticity of the emails16 (he has not accepted or denied their authenticity to date). If, the other hand, Mr Mandelson did contest the authenticity, or merely put the prosecution to proof, then adducing the PDF documents as evidence would likely be challenging. We expect in practice the UK authorities would make an application under the UK/US mutual legal assistance treaty for the original native email files, and attestations of their authenticity. These applications are relatively commonplace, but can be refused by the US on public policy grounds.

Similar issues arise with the US bank statements evidencing Mr Epstein’s 2003 and 2004 payments to Mr Mandelson, although in principle the police should be able to obtain the records from the UK banks that received the payments.

A discussion of the rules of evidence is outside the scope of this article; we assume in the analysis above that the original files would be obtained.

Many thanks to T, F, B and G for contributing their expertise to this article, thanks to W and S for writing the first draft, and to MG and S for reviewing near-final drafts.

Photo: World Economic Forum, CC BY-SA 2.0

Footnotes

There are other offences which we didn’t consider would be at all relevant and are not covered. For example: section 4 of the Fraud Act 2006 creates an offence of “fraud by abuse of position”, but it only applies if a person “occupies a position in which he is expected to safeguard, or not to act against, the financial interests of another person”. We believe this doesn’t apply to roles (like a Minister’s) where a person is acting in the financial interests of the public generally. We also considered tax evasion offences: but it is unlikely the payments to Mr Mandelson were taxable, and so these offences are inapplicable. ↩︎

We are excluding from this list the discussion in April 2010 between Mr Mandelson and Jes Staley regarding JPMorgan’s purchase of the Sempra commodities business from the (now) Government-controlled Royal Bank of Scotland Group. It is referred to obliquely and it is unclear what role, if any, Mr Mandelson had. The fact others describe him as “helpful” suggests that further inquiry is warranted, but for now we have insufficient information to consider the implications. ↩︎

The chart counts emails where a “fuzzy” search finds the word “mandelson”, or an exact search finds “petie”, “reinaldo”, “avila da silva”, or “global counsel”. We infer dates from the PDFs; this is not completely reliable. This is intentionally narrower than the categories of emails indexed by our search tool, as we are trying on this page to demonstrate the flow of the relationship; the search tool aims to provide a comprehensive index of Mandelson-related emails. A consequence of this is that the chart on the search tool page is different from the chart below. ↩︎

Of course the two individuals have no personal knowledge of any of the events in question. ↩︎

Mr Epstein had a charitable foundation, but there is no evidence it was ever discussed with Mr Mandelson or his partner, and no evidence it ever made bursaries to individuals. ↩︎

This section was not included in the original version of this article; that omission was kindly pointed out by commentators on social media. ↩︎

Note that if Mr Mandelson is hoping to hide behind a clever form of words in his written answers then he may be disappointed – a “false representation” under the Act can be express or implied (as was the old position under the Theft Act, following R v Silverman). If Mr Mandelson completed a vetting form (as is standard for ambassadorial roles) and left a relevant section blank, or used a form of wording that was accurate on its face, but misleading in substance, then that may be a “false representation” for the purposes of section 2. ↩︎

Note that there have been some references to “misfeasance in public office”. That is a separate legal concept: a “tort” under which a civil claim can be made from someone harmed by an abuse of power by a public official. It seems doubtful anyone is in a position to bring such a claim against Mr Mandelson, but in any event it is outside the scope of this article. ↩︎

There is an excellent history of the development of the offence in Attorney General’s Reference No. 3. ↩︎

The authority for this proposition is sometimes said to be R v Friar (1819) 1 Chit Rep (KB) 702 – however the case itself does not seem to support this. The point is, however, generally accepted – see paragraph 2.74 of the Law Commission report, and the CPS prosecution guidance. Both parties seemed to accept that a mayor and an MP were “public officers”, in the High Court’s quashing of the attempted private prosecution of Boris Johnson for misconduct. ↩︎

See CPS guidance emphasising a “close nexus” between the misconduct and the responsibilities of office. A helpful comparator (albeit in a different factual setting) is the long line of “sale of office / selling information” cases, where the breach is not “contrary to employer policy” but the misuse of entrusted access and authority for a non-public purpose. See CPS discussion of disclosure/sale of confidential information by public servants, and the Court of Appeal’s discussion in the “journalist and police information” context: R v France). ↩︎

Both Norman and Galley/Green involved journalism and therefore consideration had to be given to the public interest and the ECHR protected freedom of expression. No such consideration is required in Mr Mandelson’s case. See also R v France. There is an excellent article on these cases by Martin Hicks QC and Christopher Ware. ↩︎

The Market Abuse Directive (MAD) required Member States to impose effective, proportionate and dissuasive sanctions, but did not (and could not) create criminal offences directly. ↩︎

There are also prohibitions in the Market Abuse Regulation, but those post-date Mandelson’s actions. ↩︎

The UK’s interests abroad might have been “endangered” (etc) had the US been aware that the UK’s discussions with Mr Summers were being leaked, however in the event this did not happen. ↩︎

It may be more difficult for him to credibly run a defence if he does not do so; given a tactical choice between asking the jury to decide if the emails are authentic, and asking the jury to decide if he has a defence, Mr Mandelson may prefer the latter. ↩︎

![To:

From: Jeffrey Epstein

Sent: Thur 8/13/2009 7:02 12 PM

Subect: Re

he is terrific. ] want it to be his devision . | will stand by and help

all i can,,, for the space he should pur together all the numbers... rental insurance phones. heat.

ete, and then possible rent

On Thu, Aug 13, 2009 at 2:58 PM, - RE wrote:

Oh dear, he iss confused cos he has focussed hard on busing and renumg out space to give

him independent income ...!

Sent from my BlackBerry & wireless device

Front. Jethrey Epstem

Date: Thu, 13 Aug 2009 13:03-15 -0400

To. REINALDO AVILA DA SILVA’

Subject:

please send allthe info if vou intend to got to the osetopay scholl,, tuition needs. financial aid

avalible ete](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/image-39.png)

![To: Jeffrey Epstein[jeevacaton@gmail com]

From: REINALDO AVILA DA SILVA

Sem: Thur 9/47/2009 4:29 36 PM

Subject: Re Message from Reinaldo (London)

Dear Jefirey,

Hope this finds sou well

Just a brief note to thank you for the money which arrived in my account this moming

Best

Reinaldo

Reinaldo Avila

Osteopath in training

4 Park Village West

London NWI 4A](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/image-43.png)

![To: jeevacation@gmail com[eevacation@gmail com]

From: Peter Mandelson

Sem: Sun 11/7/2010 2 34 57 PM

Subyect: Fwd Rio apartment

Seat to mys bank manager Gratetul tor helpful thoughts trom my chief lite adviser

Sent from ims iPad

Bevin torwarded messave

From: Peter Mander iS

Date: 7 November 2010 [4 29 12 GMI

Subject: Rio apartment

P| ag awe dpeecussed Pan consdernne a purchase of an apartmentin Rion Ttisain](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Screenshot-2026-01-31-at-21.27.15-640x360.png)

Leave a Reply to Liz Kershaw Cancel reply