We’ve investigated many tax avoidance schemes. None of them had any technical merit – indeed many were closer to tax evasion than tax avoidance. All of the schemes, without exception, should have been disclosed to HMRC under DOTAS – the rules requiring up-front disclosure of tax avoidance schemes. None of them were.

The whole point of DOTAS was to enable HMRC to catch tax avoidance schemes early, and then either change the law (e.g. if someone found a loophole) or challenge the scheme (if it was just hopeless). In the last fifteen years, the landscape has changed dramatically. Almost all tax avoidance schemes are of the “hopeless” rather than “loophole” variety. And so the only way the promoters can stay in business is by breaking the law and avoiding DOTAS.

My view is that many promoters are criminals, but criminals who are very hard to prosecute under current law. My view was (and is) that the law should be changed to make prosecution a real possibility. Only then would we be able to deter the rogue promoters. My proposal was that failure to disclose under DOTAS should be a criminal offence, and I was delighted to see this adopted by the Government in the package it published back in the Spring.

Except I’ve changed my mind – following a series of discussions with HMRC and advisers.

I changed my mind partly because of two serious problems with the proposal – one that can be fixed, and one that can’t. And partly because two of the other elements in the Government’s package render it unnecessary.

I discussed these issues at the House of Lords Finance Bill Sub-Committee on Monday (starting at 07:45):

The problem we can fix

Many representative bodies have complained that the proposal as it stands is likely to create a chilling effect on ordinary tax advice, or swamp HMRC with unnecessary disclosures – or both.

DOTAS is complex, and honest tax advisers – who currently “take views” that uncontroversial arrangements aren’t disclosable – won’t be able to be as relaxed when breach of DOTAS is a criminal offence. So some firms might move out of tax advice altogether – a bad thing for business and HMRC alike. Others could respond by disclosing everything out of prudence.

This is an important criticism, but one that can be addressed without too much difficulty. The answer is to create an “bona fide firm” defence to the criminal offence so that mainstream firms need have no fear that a one-off accident could result in criminal liability.

Mainstream firms look really different from the promoter firms. Mainstream firms advise varied clients doing varied things, ,and it would be exceptional for any of those things to be caught by DOTAS. The promoter firms typically run a very small number of schemes (often just one), marketed in high volumes.

So we can create a defence that applies to any firm that can demonstrate that at least 90% of its tax-related business (measured by fee income) relates to bona fide tax advice.1 Tax advice would be “bona fide” for this purpose if either it relates to an arrangement which is not properly disclosable under DOTAS, or it is disclosable but was properly disclosed.

I expect every single mainstream firm that provides tax advice, large and small, would be comfortable the defence applied to them, and so would not suffer the chilling effects that concern the CIOT.

The “chilling effect” problem is therefore not insurmountable.

The problem that can’t be fixed

The more challenging issue is that the same complexity that scares normal tax advisers will, perversely, make the actual criminal tax advisers more relaxed.

Take a look at the judgment in the Hyrax case. This was a low quality tax avoidance scheme which in my view had no reasonable prospect of success. It failed to disclose under DOTAS by running extremely poor arguments that in my view also had no reasonable prospect of success. It still took the Tribunal 56 pages to throw out Hyrax’s appeal.

The Hyrax judgment shows a KC (who I expect designed the scheme) running a long series of complex but meritless arguments. The Tribunal had no difficulty dismissing them, but arguments like these would be far harder for a jury to evaluate, and could easily create reasonable doubt. That’s particularly the case when promoters have an opinion from a KC who is willing to bless the most far-fetched arguments. Until the Bar gets its house in order, it’s going to be far too easy for a promoter to manufacture an excuse for its actions.

In the course of the recent consultation, I and other advisers spoke to knowledgeable people at HMRC, and we came away with the distinct impression it might be challenging to present any DOTAS case to a jury. We then spoke to retired HMRC inspectors with experience of tax prosecutions, and then to barristers specialising in “white collar” crime (doing both prosecution and defence work). All of them thought that prosecutions would be problematic – one barrister said the offence might be “unprosecutable”.

Our team has explored ways that the offence could be made simpler, but unfortunately none seem very workable. The various forms of simplicity we’ve considered all either risk criminalising innocent firms, or present too many loopholes for criminal firms.

So I’m disappointed to have to conclude that my basic concept of criminalising DOTAS breaches is not viable.

I’d love to be wrong, and for there to be a way to design an offence that neither criminalises the innocent or lets the guilty off the hook, but I’m not currently seeing it.

The alternative

My original thought process was that rogue promoters were breaking the law without consequence, and severe sanctions were required to stop this.

That’s still my view, but I think the same aim may now be achieved by two other measures in the Spring package:

Universal stop notices

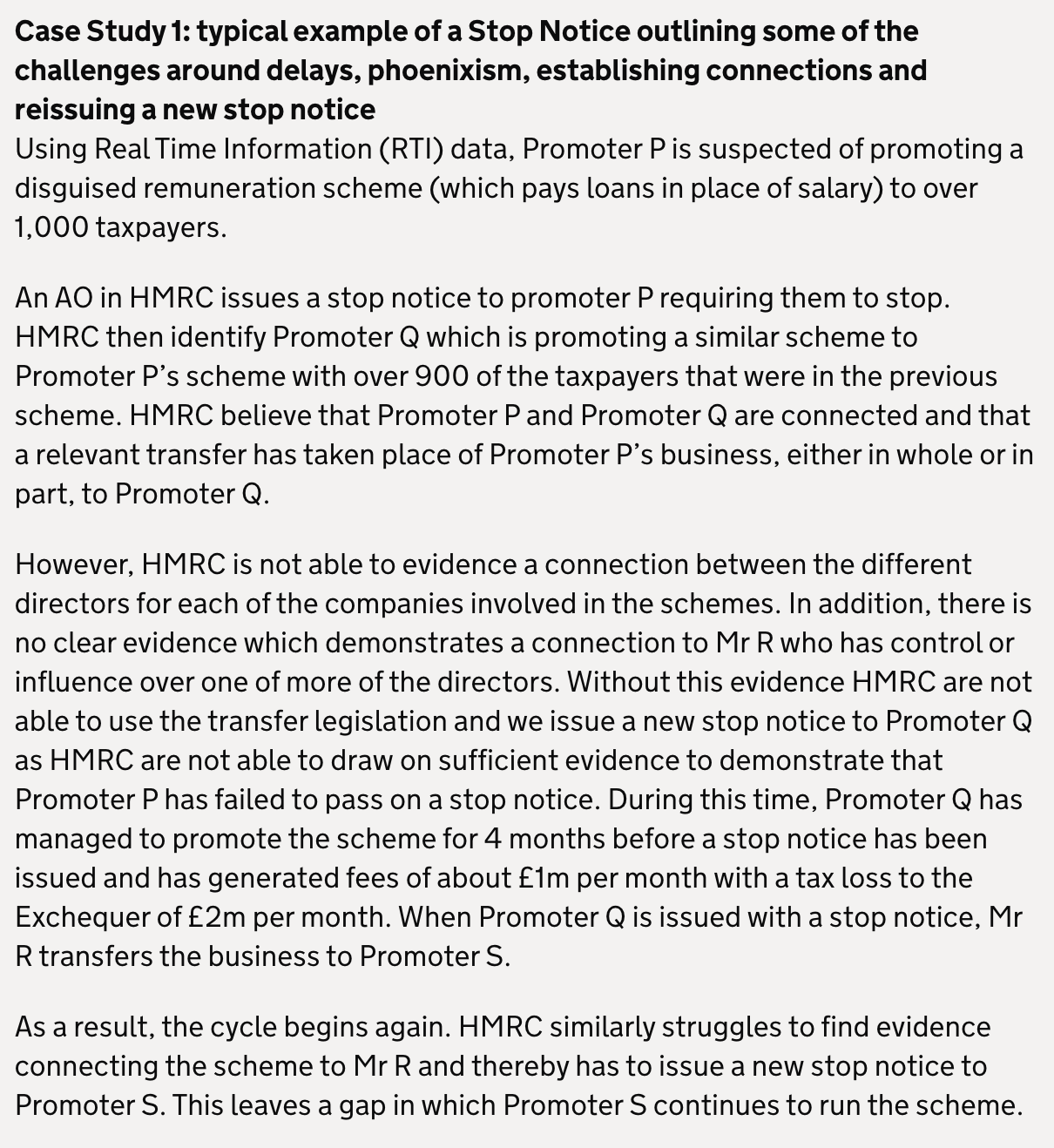

HMRC currently has a power to issue a “stop notice” to the promoter of a tax scheme, making further promotion of that tax scheme a criminal offence.2 The problem is that the people ultimately behind these schemes hide themselves behind trusts, nominee directors and nominee shareholders. HMRC will issue a stop notice to one entity, and the promoter will simply move its business to another (very possibly run by different frontmen).3 This example in the HMRC consultation document is an accurate reflection of what’s been happening:

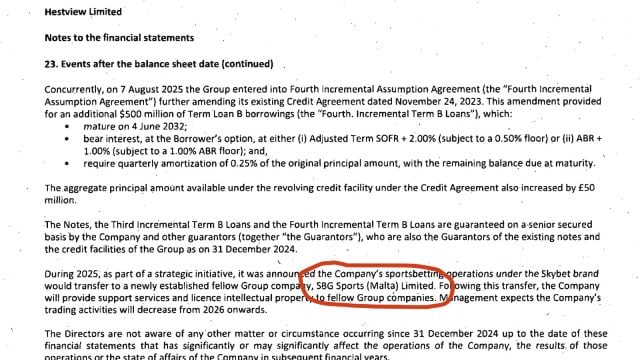

The Government is proposing to end this game of “whack a mole” with a “universal stop notice“. This would empower HMRC to issue a notice specifying a scheme; no person could then promote or enable that or any similar scheme. Anyone who did would commit a criminal offence, as would any person controlling or influencing them.

The key question is whether HMRC is able to speedily identify schemes, and HMRC and the Parliamentary drafting team are then able to craft USNs which encompass all the variations of the schemes that the promoters (who are smart and devious) will be able to come up with. If they can, then the USNs should do the job of criminalising the most significant areas of tax avoidance.

DOTAS penalties

One of the reasons promoters ignore DOTAS is that it’s hard for HMRC to apply penalties.

Under the current rules, failing to disclose a tax avoidance scheme under DOTAS can lead to daily penalties of up to £600. These penalties must be imposed by the Tax Tribunal on application by HMRC.4 If the failure continues, HMRC can apply again for higher “continuing” daily penalties of up to £1 million in total. HMRC cannot impose these penalties itself – each one requires a formal tribunal process. There are also smaller fixed penalties, which HMRC can issue directly, for users who fail to include a scheme reference number on their returns (typically £5,000–£10,000), with a right of appeal to the tribunal.

This regime has proved weak. The tribunal process is slow and expensive, and promoters can often dissolve or re-incorporate before penalties are determined. Even when penalties are imposed, they are rarely paid – as in Hyrax, where the tribunal approved a £1 million DOTAS penalty but nothing was ever recovered. The result is that promoters routinely breach DOTAS with little real consequence.

The Government’s Spring 2025 package proposes to change this by allowing HMRC to impose DOTAS penalties directly, bringing the rules into line with other modern anti-avoidance regimes. Penalties would still be appealable to the tribunal, but HMRC could issue them immediately, without needing a prior tribunal order.

This means HMRC should be able to issue DOTAS penalties as a simple procedural step, whenever it identifies a tax avoidance scheme that is being marketed but has not been disclosed under DOTAS. The process should be much faster, making it harder for promoters to evade penalties by delay or phoenixing.

If HMRC wants to change the avoidance landscape then it will have to act aggressively, and be willing to use the joint and several liability rules to pursue the individuals behind the schemes if/when the companies fold. I also feel that maximum penalties of £1m isn’t enough – the HMRC example of a promoter making £1m in fees per month is not fictional. I would make the maximum penalty the higher of (1) £1m, and (2) 150% of fees charged.

The next step

I still think more is needed. It’s offensive to me and many other tax advisers that flagrantly doomed tax avoidance schemes are still sold at scale. It’s become a mis-selling problem as much as it is a tax problem – lives are ruined when these schemes are sold to people (often people on modest incomes).

Part of the answer is regulation (and regulation that goes further than the current Government proposal, which won’t apply to most scheme promoters). But it’s not clear that existing regulation is working. The Bar in particular has tolerated bad actors for too long. If the professions won’t regulate themselves then Government should step in.

Footnotes

An anti-avoidance rule may need to be added, so the defence wouldn’t be available if a firm artificially created non-DOTAS business to “swamp” its main DOTAS business. ↩︎

“Stop notices” were a new power granted to HMRC in 2021, with the rules now in section 236A Finance Act 2014. The effect of a stop notice is that the recipient of the stop notice mustn’t promote the specified arrangements, or anything similar to them. The stop notice also requires the recipient to provide HMRC with detailed information on its clients, and to pass details of the stop notice to those clients. ↩︎

In theory the existing rules should deal with that. The effect of a stop notice also applies to (amongst others) anyone who controls, or has significant influence, over the recipient of the stop notice. And if the recipient transfers its business to another person, then the stop notice applies to them too. All of this is in theory: in practice the entities tend to be offshore and highly opaque, and it is difficult or impossible for HMRC to prove the relationship between them. ↩︎

The reason is that DOTAS penalties are imposed by s98C Taxes Management Act 1970. Section 100 TMA provides that most TMA penalties can be imposed by an HMRC officer; but s98C is excluded from this. ↩︎

Leave a Reply