The “tax gap” is the difference between the tax HMRC should collect and the tax it actually collects. Over the last nineteen years, most of the tax gap has fallen by two-thirds – a remarkable achievement. But a deep dive into HMRC’s latest tax gap statistics shows that HMRC has lost control of small business tax: 40% of corporation tax due from small businesses is not being paid. The small business tax gap rose sharply during the pandemic – and hasn’t fallen since.

If HMRC had closed the small business tax gap as effectively as it closed other tax gaps, it would collect £15 billion more each year.

The FT’s report on the new data is here. Our analysis is below.

The tax gap

The difference between the tax that should be paid and the tax HMRC actually collect is the “tax gap”. HMRC say it’s £46.8bn.1 There are a large number of uncertainties, but HMRC’s tax gap estimate work is generally regarded as world-leading.2

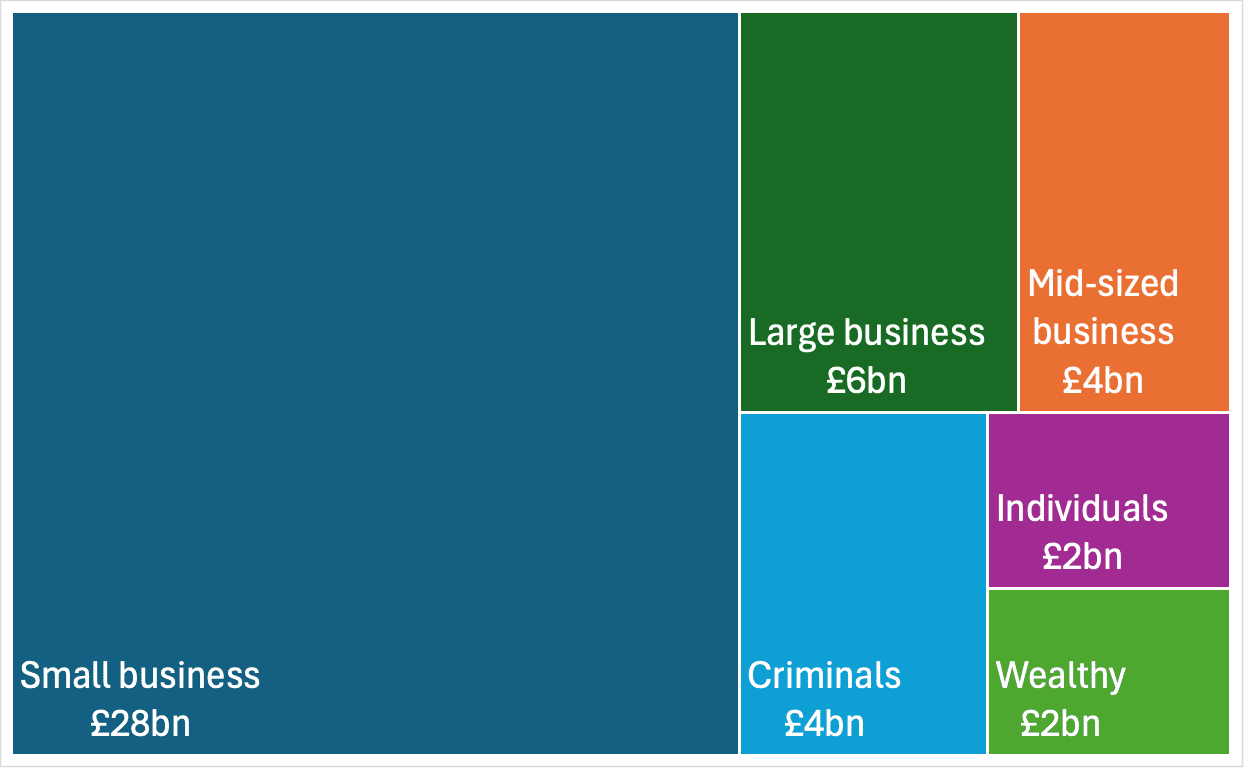

Where is most of the tax gap?

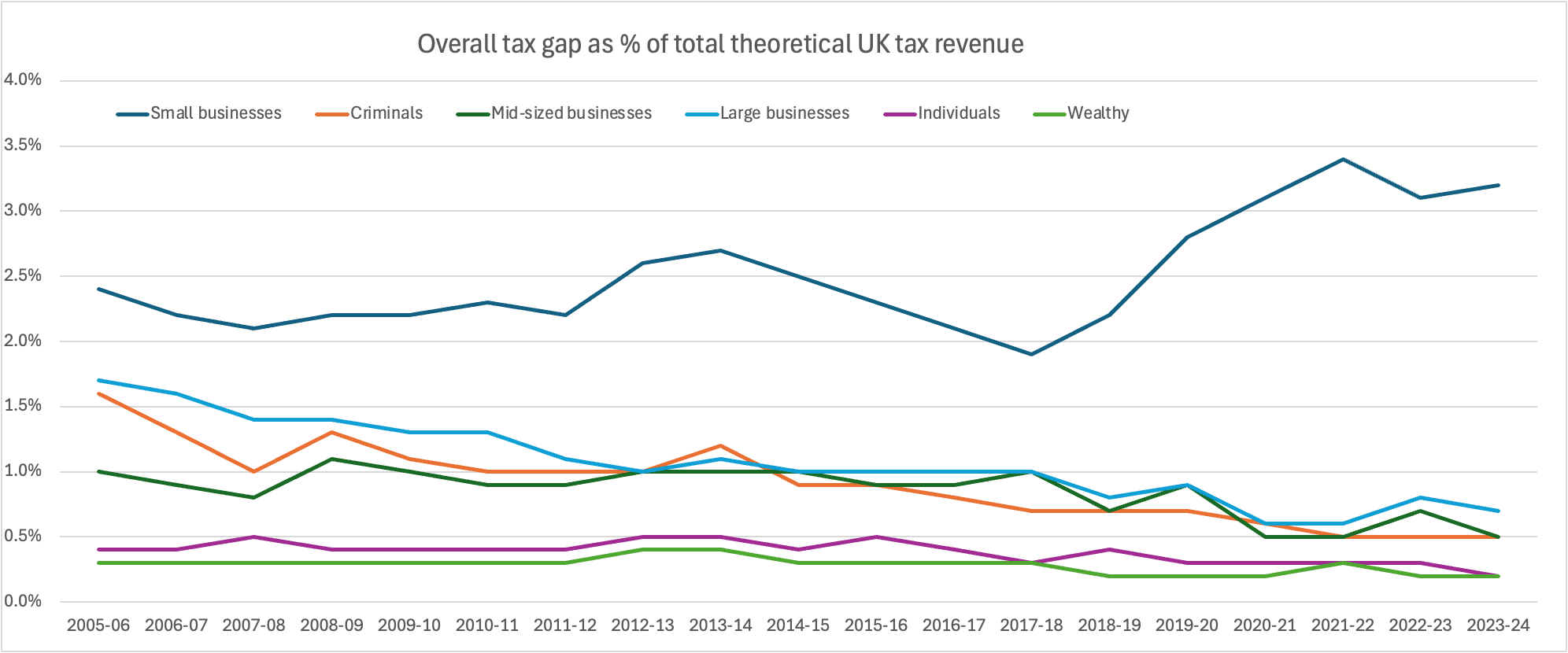

Most of the tax gap is from small businesses, meaning businesses with a turnover of less than £10m and less than twenty employees:34

What’s happened to the small business tax gap?

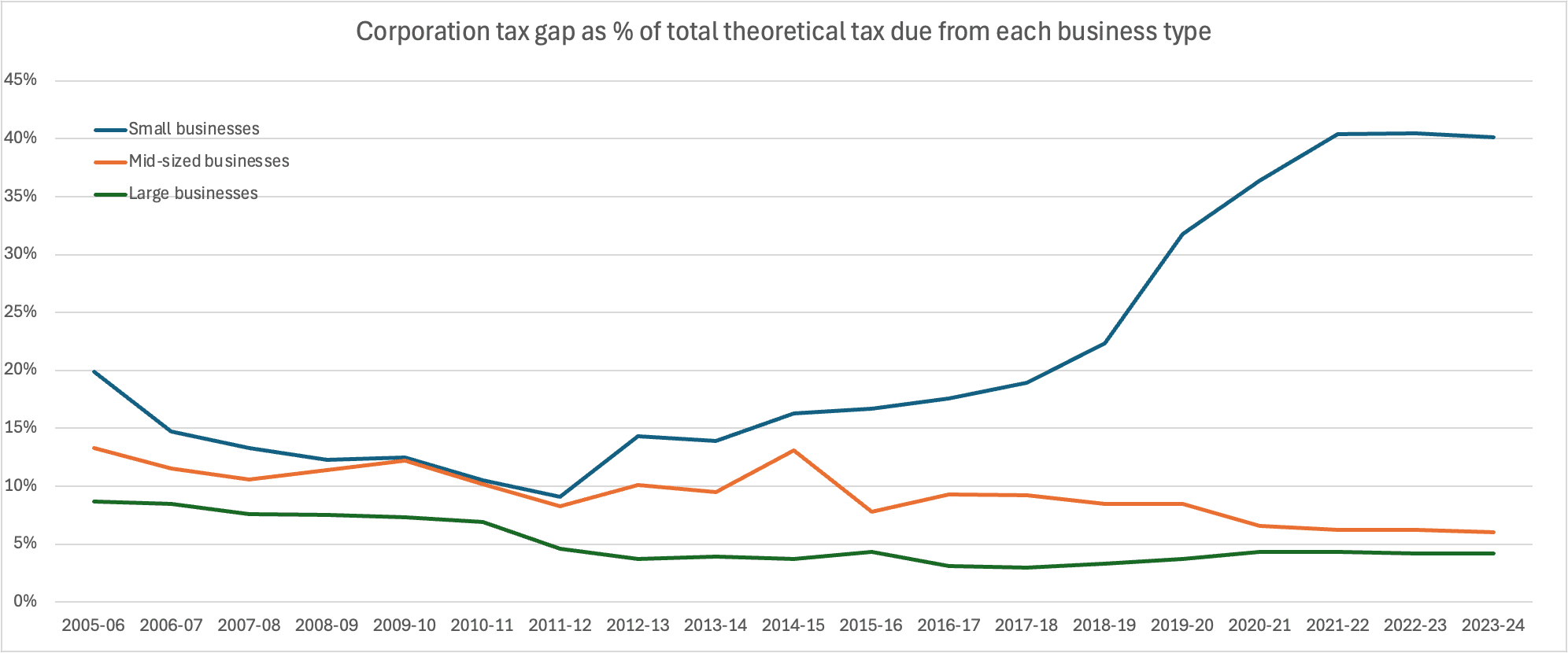

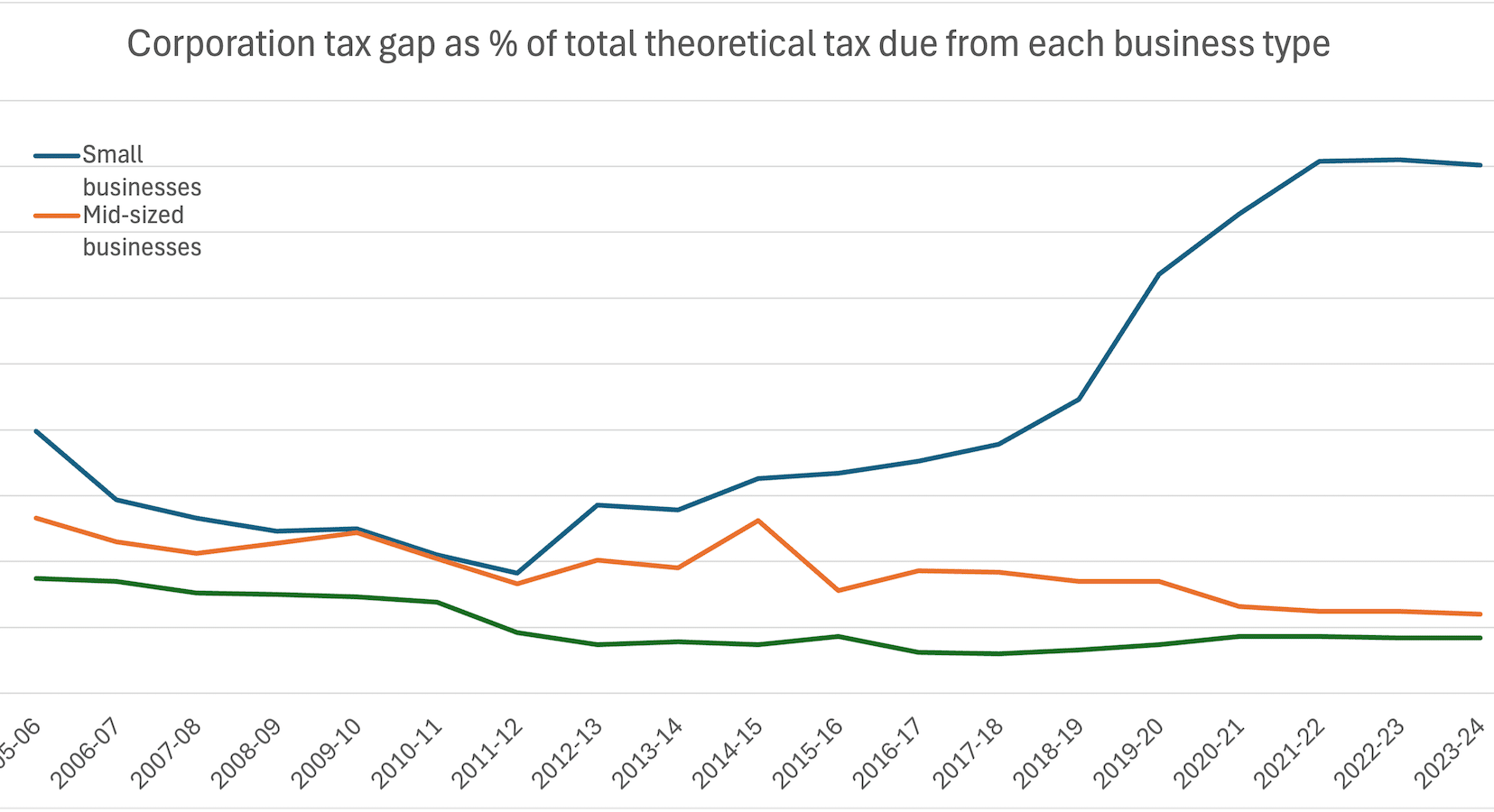

Small businesses have always been the most likely sector to pay the wrong tax (whether by accident or design). However in the last few years, something has changed:5

That sharp uptick in 2019/20 may have initially been caused by the pandemic, but we don’t see that effect for other types of taxpayer, and its now clear that the trend didn’t slow down after the pandemic.6 There have been a series of upward statistical revisions to data for recent years. These took the 2022/23 small business corporation tax gap from 32% to 40% (with the 2021/22, 2022/23 and 2023/24 figures being essentially identical). However HMRC sources have confirmed to us that these revisions don’t call earlier figures into question, and so the apparent trend in the data is real, and not just a statistical artefact.

It is astonishing that 40% of all corporation tax due from small businesses is now not being paid.

There’s a sharp contrast with the large and mid-sized business corporation tax gap, which HMRC has been remarkably successful at closing.

The wider picture

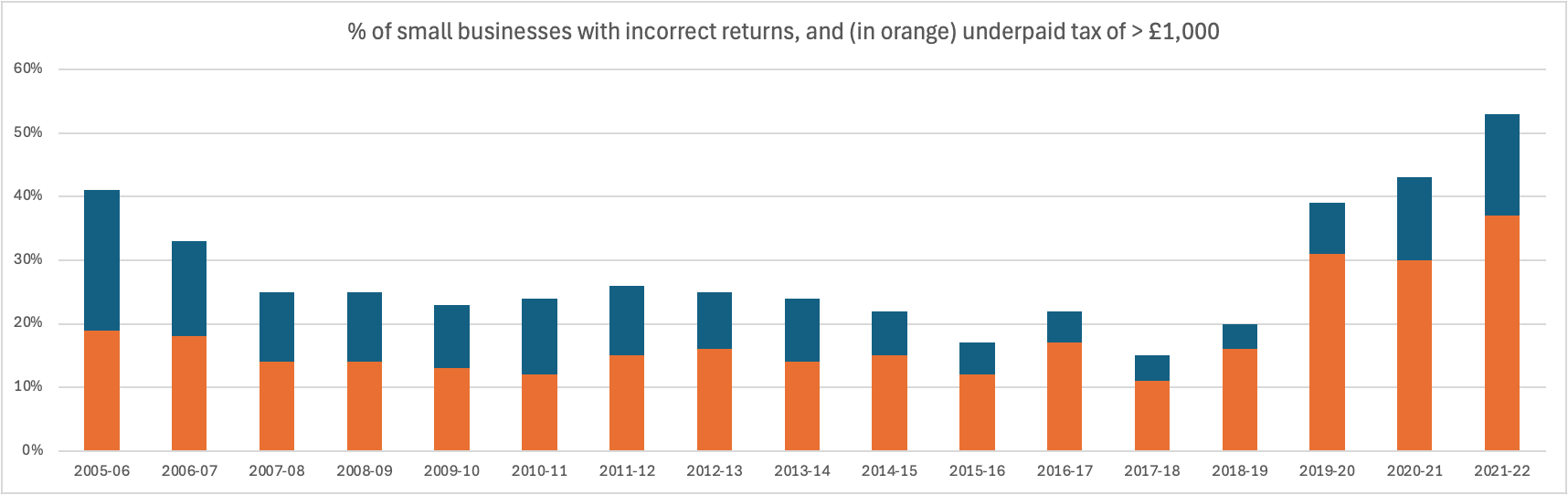

The problems appear to be widespread. HMRC data shows that well over a third of small businesses now underpay their tax by more than £1,000 – a doubling since 2018/19.

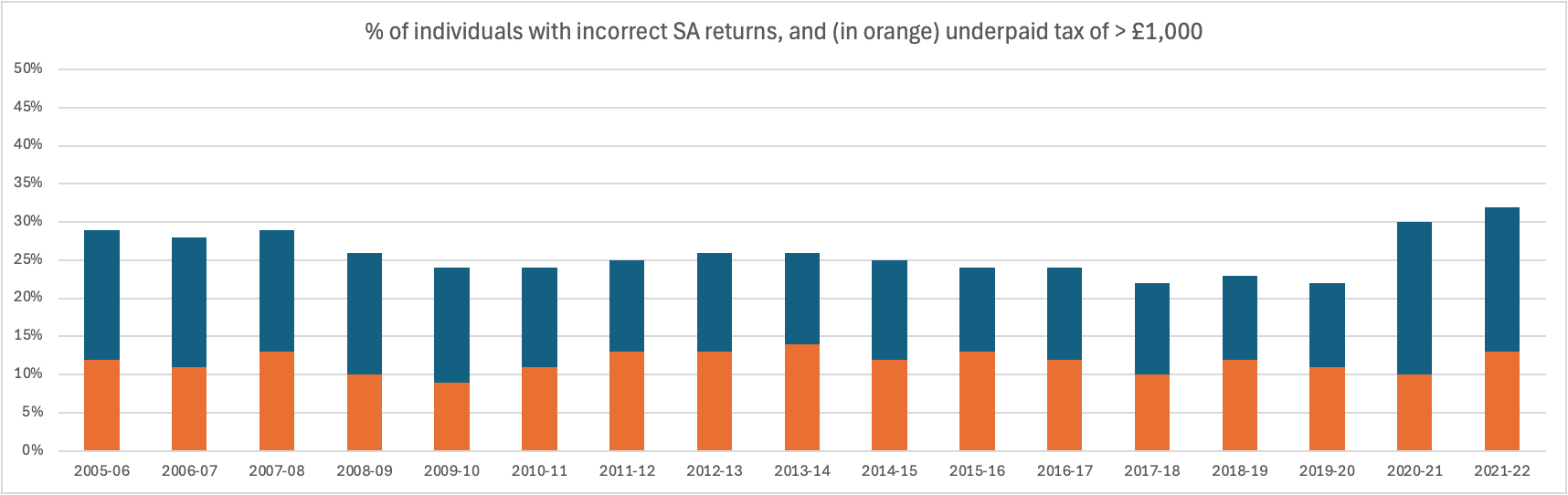

An obvious explanation is that this is a post-Covid effect. However there’s no such trend seen if we look at the figures for tax returns from individuals:7

And it’s worse than this. The small business tax gap isn’t limited to corporation tax. If we step back and look at the HMRC figures across all taxes we see another dramatic divergence:8

HMRC have generally done an excellent job shrinking the tax gap, with declines across the board. But after 2017/18 something changed.

The small business tax gap increased from 2.4% of all UK tax revenues in 2005/6 to 3.2% in 2023/24. The rest of the tax gap fell precipitously over that period – large businesses from 1.7% to 0.7%; mid-sized businesses from 1.% to 0.5%.

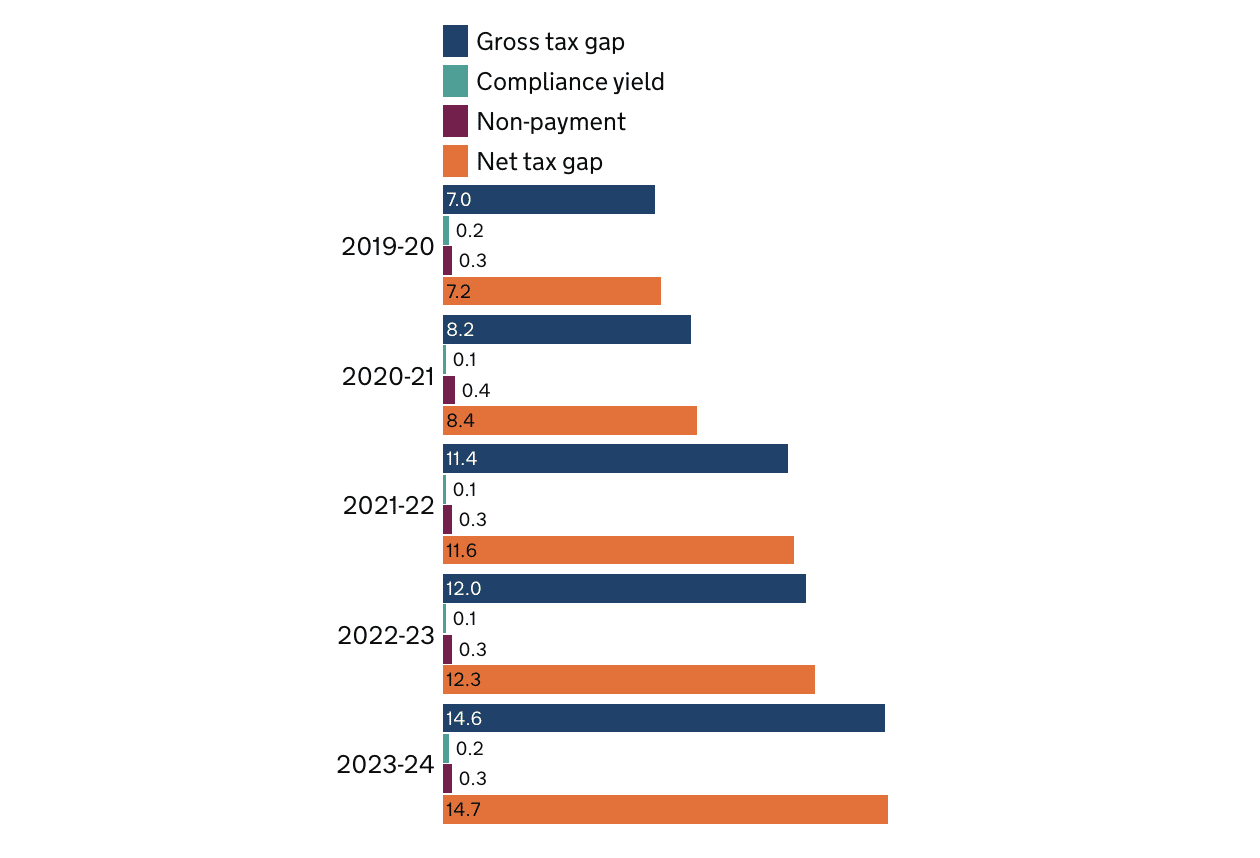

But whilst the small business tax gap has increased, the efforts to close it have not. This chart from HMRC’s report shows that the tax gap doubled over the last five years, but “compliance yield” (the return from HMRC’s investigation/compliance work) didn’t change at all:9

How much are we losing?

If the small business tax gap had declined at the same rate as the mid-sized business tax gap, HMRC would collect an additional £15 billionevery year.101112).

What is going on?

Small businesses have always been responsible for the majority of tax evasion and non-compliance. The cliché of men in white vans receiving payment in cash isn’t that far from the truth. This explains why the small business tax gap is hard to close. It doesn’t explain why it’s increased.

We believe there are two key factors: a decline in HMRC customer service to small companies, and an upsurge in avoidance and evasion which doesn’t really relate to small companies at all, but is technically allocated to them.

A decline in HMRC customer services

There have been many anecdotal reports of a decline in HMRC customer service (see page 31 of this CBI report and this from the Chartered Institute of Taxation). It’s not merely that HMRC funding has failed to keep pace with inflation; its most experienced personnel were moved onto other projects, particularly Brexit and the pandemic, and didn’t move back (see paragraph 1.8 onwards in this National Audit Office report). We are also hearing about long-term problems with the quality and length of staff training deteriorating.

It isn’t surprising that it’s small business that suffers the most from these problems.

We’ve talked before about realistic ways that the tax gap could be reduced.

Additional funding is a pre-requisite, but on its own isn’t enough.

We are increasingly hearing about problems with the length and quality of training new HMRC employees receive. Customer service needs to be prioritised. HMRC needs to get back in touch with taxpayers, so it can assist the vast majority that are trying to be compliant, and proactively identify those that are not. HMRC’s approach to investigations and disputes needs to change: right now it often pursues weak and irrelevant cases, cases that are oppressive to taxpayers (and sometimes inexplicable and disturbing) but at the same time misses what’s happening on the ground.

Avoidance and evasion

We are inundated with reports of tax avoidance and evasion – more than we can ever investigate. Most of these are relate to small businesses. Some are “traditional” tax avoidance schemes marketed to small businesses. But a great many involve companies established to act as employers of contract workers, evading or avoiding tax on the workers’ remuneration (usually without the workers’ knowledge). These structures are little more than scams, but there are vast numbers of them, and they make up most of the schemes listed on the avoidance pages on the HMRC website. Our sources at both HMRC and in the tax avoidance “industry” have told us they believe these schemes cost HMRC £5bn each year. And the critical point: these schemes are technically classified as small businesses.

So it’s our view, albeit based on anecdote and sources rather than hard evidence, that much of the growing small business tax gap is driven by remuneration tax avoidance schemes.

Another possibility is that a media focus on tax avoidance by billionaires and multinationals has taken too many headlines, and distracted too many people, from what the majority of tax avoidance and evasion actually looks like. We should follow the data.13

What needs to change

One answer is funding. However, HM Treasury mustn’t just shower HMRC with additional funding; new funds need to be carefully directed and managed. Failures to deliver important cases, or drop bad cases, should be investigated; not to blame individuals, but to find out what, systemically, is going wrong, and how to fix it.

Another answer is having the right tools to attack aggressive avoidance. The recent Government consultation is very promising – but HMRC will need both focus and funding to make any new legislation work.

HMRC’s success in reducing the tax gap over the last 20 years suggest that its failure to close the small business tax gap can and should be remedied. £15bn is an extraordinary sum to lose behind the administrative sofa.

Footnotes

Other figures are sometimes quoted, but they are statistically naive. Richard Murphy produced a figure of £90bn back in 2019, but he did this by adopting a “top-down” methodology which, as HMRC and the IMF (page 46 here) have explained, requires a series of significant adjustments which Murphy does not make. Murphy’s estimate also fails the “smell test”. It requires us to believe HMRC are missing more than 95% of all tax evasion – that does not seem plausible given that HMRC conduct random audits of businesses (absent HMRC being corrupt, which is Murphy’s view). We’re unaware of any tax expert who believes Murphy’s approach is credible, and no country has adopted it. ↩︎

Estimating the tax gap is a very difficult exercise, with numerous sources of error and uncertainty. HMRC does an impressive job to rigorous standards, generally believed to be the best in the world (most tax authorities only produce tax gap figures for VAT, which is a far simpler job given that it can be estimated with reasonable accuracy “top-down” from national accounts data). About ten years ago, HMRC’s homework was favourably reviewed by the IMF, who made various recommendations, most of which have been followed. More recently it was also reviewed by the Office for National Statistics. ↩︎

It’s sometimes said that the estimates ignore offshore avoidance. This is not quite right, and there are two separate points here.

First, our work identified that HMRC does not systematically match up offshore account reporting with self assessment data. But that is different from saying that offshore is not included in HMRC’s tax evasion estimates. At most, HMRC’s estimate may be missing some evasion that would be identified by cross-checking HMRC’s sources of data. If so, the amounts are likely modest.

Second, HMRC’s tax gap does not include areas where something we might describe of as “avoidance” is actually permitted under the rules – for example the “double Irish” structure Google used prior to 2015. So in 2015 it was a very valid criticism to say that the tax gap estimates ignore multinational tax avoidance. However, things have changed since 2015. The many anti–avoidance rules implemented post-2015 make it much harder to see what “avoidance” remains permissible. Even the Tax Justice Network estimates (of which we’ve been very critical) show multinational avoidance costing the UK less than £2bn. This second criticism therefore feels of limited relevance today. ↩︎

Also note that the definition of “avoidance” doesn’t encompass planning that’s clearly permitted by the rules (even if many people wish it wasn’t). So, for example, the big tax advantages for non-doms aren’t a result of tax avoidance – they’re how the rules work. Ditto carried interest, avoiding SDLT on commercial property using enveloping, etc. More on the definition of “tax avoidance” here. ↩︎

Our source for this, and all the data in this article, are the HMRC tax gap tables – see tables 5.2, 5.4 and 5.5. ↩︎

The only other taxes where the tax gap has gone up over this period are inheritance tax (which likely results from so many more estates becoming subject to the tax) and landfill tax (we don’t know why that is; it’s an area where our team has no knowledge or expertise) ↩︎

Overall errors crept up slightly but errors of over £1,000 have been broadly static. ↩︎

This is from table 1.4 of the HMRC tax gap tables. ↩︎

Many thanks to Heather Self for identifying this point. ↩︎

As the figure is based on the HMRC tax gap statistics, it is subject to considerable uncertainty; we cannot quantity the uncertainty (given the lack of quantitative error analysis in the HMRC statistics). ↩︎

About £9.5bn corporation tax and £5.5bn other tax (mostly VAT). We can’t show this directly, as there are no detailed statistics for VAT non-compliance in the tax gap tables, and no figures for VAT revenues from small business in the VAT statistics. But HMRC figures show small business PAYE compliance has dramatically improved, with the tax gap reducing by 2/3 – we expect this is due to the widespread move towards outsourced automated PAYE services. Other taxes are not significant to most small businesses, and so by a process of elimination we can be reasonably confident that most of the non-CT tax gap here is VAT ↩︎

It can seem counter-intuitive that the corporation tax gap is bigger than the VAT gap, not just in this case but generally. Since VAT is 20% of turnover, and corporation tax (in this period) 19% of profit, if someone evades tax won’t the VAT loss be greater? Why is the corporation tax gap bigger than the VAT gap? Primarily because VAT compliance is (broad generalisation) easier than corporation tax compliance. It’s your turnover (if you’re a business that only supplies standard rated products) less your inputs. Corporation tax is much more nebulous – what ends up as your “profit” is often less than obvious. What’s more, VAT is hard to avoid or evade these days – sales to customers are visible; sales to business customers leave a paper trail. There’s an additional factor for small companies that every company pays corporation tax, but only companies with over £85,000 of revenue (in 2023/24) are subject to VAT. ↩︎

Obviously that doesn’t mean HMRC should reduce its efforts to prevent avoidance/evasion by the wealthy and large business, or that we shouldn’t be talking about it. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Kerry Stephens Cancel reply