Today’s episode of Untaxing is about Jaffa cakes and VAT.

With the benefit of hindsight, that’s a very small VAT issue on a day when VAT has become a very large geopolitical issue.

Donald Trump is considering applying tariffs to much of the world because of VAT. He believes it’s a tariff. You’ll be unsurprised to hear that I disagree. But the details of why he’s wrong are interesting, and go beyond “all UK buyers pay VAT so there’s no discrimination”.

So, whilst there are many good articles explaining why VAT isn’t a tariff, I’ve written one with more detail, more footnotes, some beer, a theorem from 1936, and a callback to Jaffa Cakes.

What is a tariff?

A tariff is a type of tax which applies to imported goods but not locally-produced goods. That’s the World Trade Organisation definition (and tariffs are very much its thing) as well as the approach followed by the OECD in its own research.

Most countries impose tariffs on a variety of imports, usually with a complex series of rules (“schedules“) setting out which tariff applies to which goods.

So, for example, the UK imposes a 10% duty1 on importing most types of car. A car showroom buying cars from a British car manufacturer doesn’t pay this; a car showroom buying from a foreign manufacturer does. This is a tariff.

What isn’t a tariff?

Tariffs are sometimes called “duties”. That’s confusing, because not all duties are tariffs.

Take beer duty.

The UK imposes a £21.78 duty on each litre of alcohol contained in beer. Beer brewed in the UK to be sold in the UK is subject to the duty at the point it is produced. Beer brewed outside the UK is subject to duty when it’s imported.

Another feature: if beer is brewed in the UK to be exported then it’s generally not taxed.

This kind of tax is often called “destination-based”, because whether the duty applies depends entirely on where the consumer is, and not on where the producer is. Most countries in Europe and beyond also have destination-based alcohol duties.2

Another example of a destination-based tax is the various US State3 sales taxes. These generally apply to sales of goods and services to consumers in the State, whether the seller itself is in the State or outside it; they don’t apply to in-State sellers exporting to another country. 4

A destination-based tax is not a tariff, because it applies to both locally-produced and imported goods. There are (necessarily) different collection mechanisms for foreign and domestic sellers, but the overall tax result is broadly the same.

Why is VAT different?

VAT, in principle, is just another destination-based tax like beer duty or New York State sales tax. It’s charged where the ultimate consumer is in the UK, and not charged where the ultimate consumer is outside the UK. The location of the seller is irrelevant.

But the administrative detail of how VAT works is very different.

Sales taxes apply once and once only, to the final sale to the consumer. A business selling a car to someone living in New York has to charge State and local sales taxes. The rest of the supply chain – the suppliers of the raw materials, the car manufacturer, etc – is unaffected by the tax.

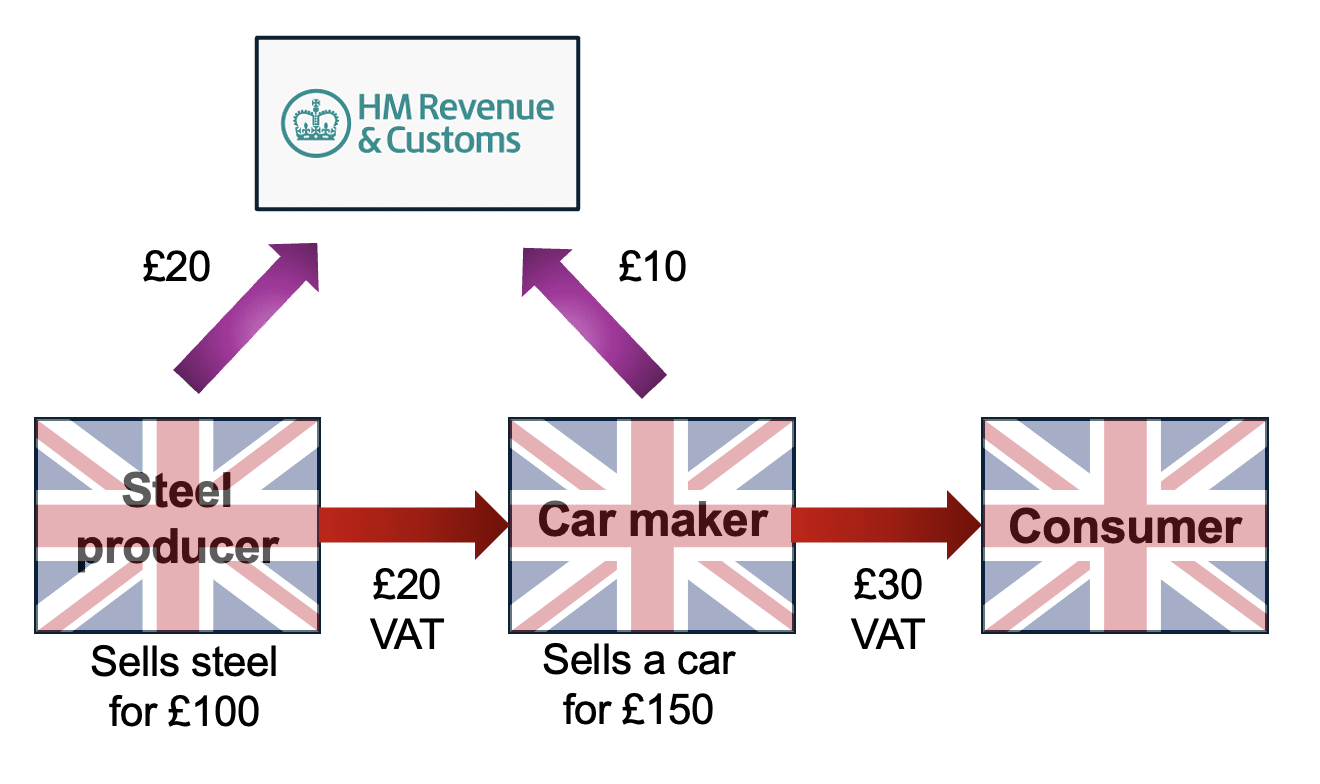

VAT applies at every level of the supply chain – to the “value added” at that level. To take a simplified example:

So:

- When the producer sells the steel for £100, it has to charge 20% VAT – so it charges the car manufacturer £100 plus £20 VAT, and accounts for the £20 to HMRC.

- When the car maker sells the car for £150 it also has to charge 20% VAT, so the consumer pays £180. The car maker recover the “input” VAT of £20 it paid to the steel producer, so it accounts to HMRC for £10 – i.e. £30 minus £20.

- The overall VAT paid is £30 – just as if this was a simple 20% sales tax only paid by the car maker. But it’s collected at each step in the supply chain.

- Of course in reality there will be hundreds or thousands of businesses in the supply chain, each collecting a small amount of that final £30 of VAT.

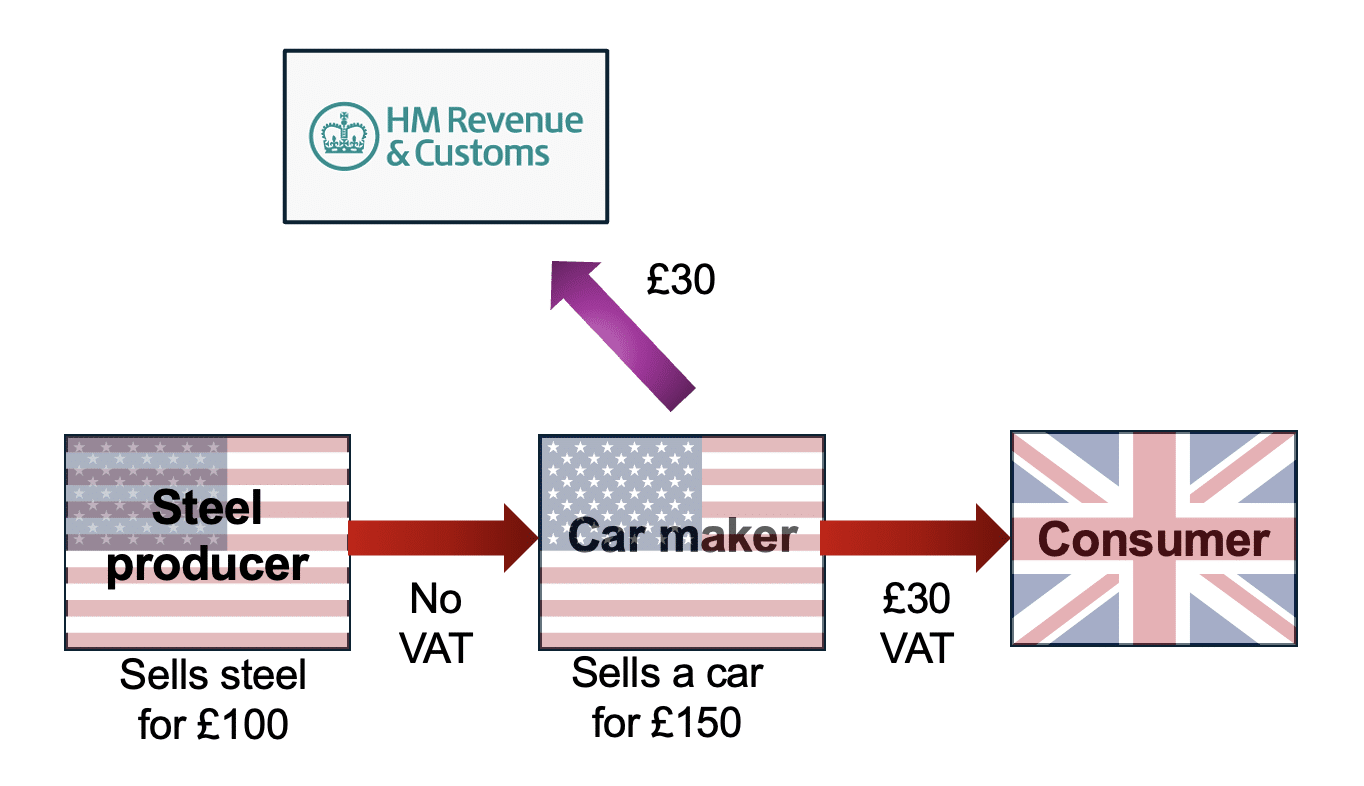

And here’s the result if it’s a US business selling to a UK consumer:

There is of course no VAT when the US steel producer supplies the steel to the US car maker. The only charge is “import VAT” when the car maker imports into the UK. The result, however, is the same: £30 of VAT.

I’ve used the UK in these examples, but the result would be the same across the EU (as UK VAT remains almost identical to EU VAT). It’s also the same in most – and possibly all- the other countries that apply a VAT or GST.5

Why is VAT so complicated?

Why does VAT work this way, when the ultimate result is the same as a simple 20% sales tax? Wouldn’t it be simpler to just work like a US State sales tax, and collect that 20% all in one go at the final sale?

There is only one reason why VAT works this way: tax evasion.

- The “final sale” can be a tricky concept to apply. If I’m buying a car, I can easily claim I’m a business, and so (illegally) escape sales tax. The seller has limited ability or incentive to check my bona fides. VAT doesn’t have that problem, because a seller charges VAT to everyone. A consumer can’t recover VAT; other people can. We can therefore expect much higher rates of tax evasion under a sales tax than a VAT.6

- You can try to limit the “false business” problem by putting stringent rules on sellers; but then you can have the opposite problem, with sales tax being applied when it shouldn’t be. You’d then have a “cascade” of sales tax hits instead of just one. That would be economically damaging.

- VAT collects from everybody. No need to work out if you’re selling to a business or a consumer.7

- And another big advantage: if almost everyone in the supply chain is filing VAT returns then it’s often easy for a tax authority to spot the ones who aren’t. VAT creates its own audit trail.

- And if all of this fails, and only one person in the supply chain fails to pay VAT, then it’s only their value-add which goes untaxed.

It’s therefore received wisdom amongst tax economists that US-style sales taxes are only viable up to a certain percentage of the sale. Beyond that, and to the levels that European economics require to fund their spending, sales taxes would be widely evaded and/or would be economically damaging. And even at the US levels, VAT would be preferable.

Why does Trump think VAT is a tariff?

One possibility is that he doesn’t understand that a domestic producer selling into the UK faces the same VAT as a US producer.

Another possibility is that he misunderstands how VAT is credited when UK businesses are exporting.8

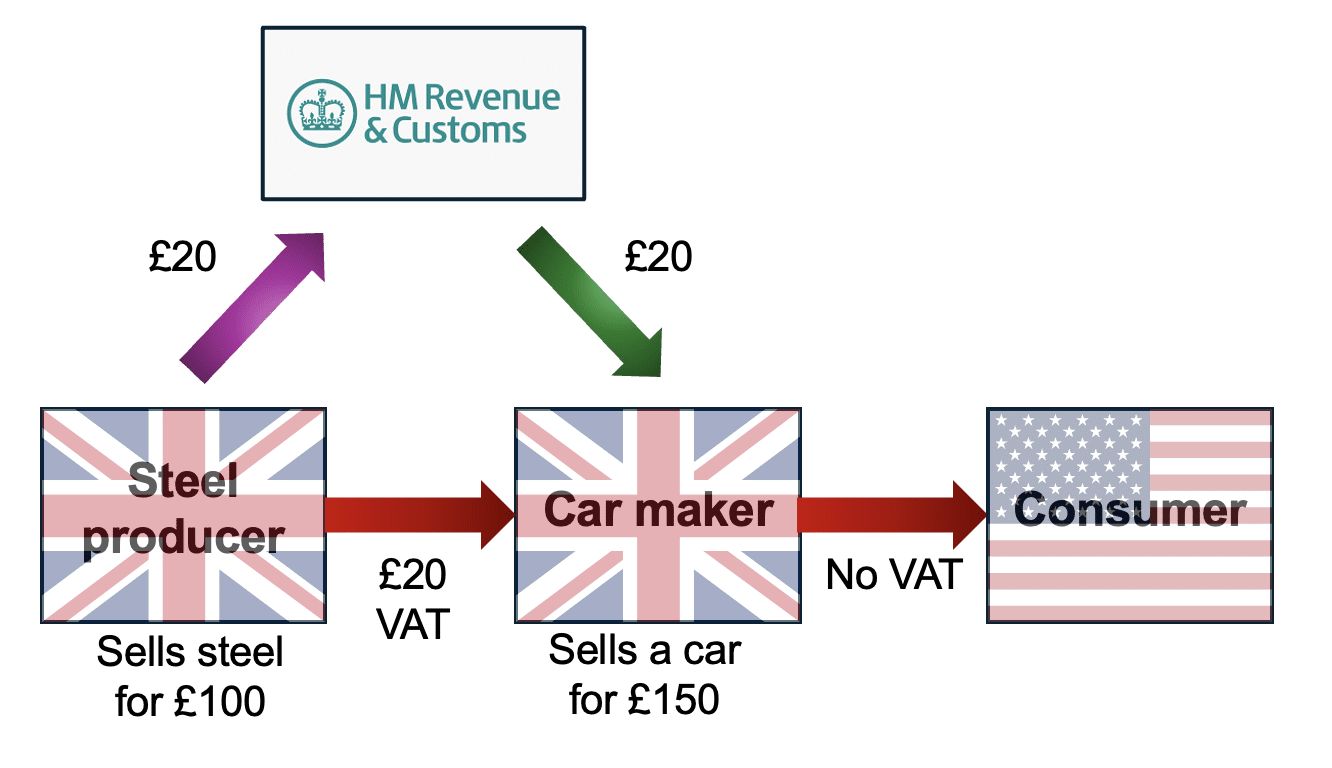

Here’s how it works:

The car maker has charged no VAT on its sale to the final consumer, because he or she is outside the UK. But there has still been £20 VAT collected in the supply chain. That’s the wrong result – and the answer is that the car maker can “recover” the £20 in the same way it did in the first example above.

Since it’s a sale to a US consumer, in some US states there would be sales tax on the final sale. It’s unaffected by the supply chain.

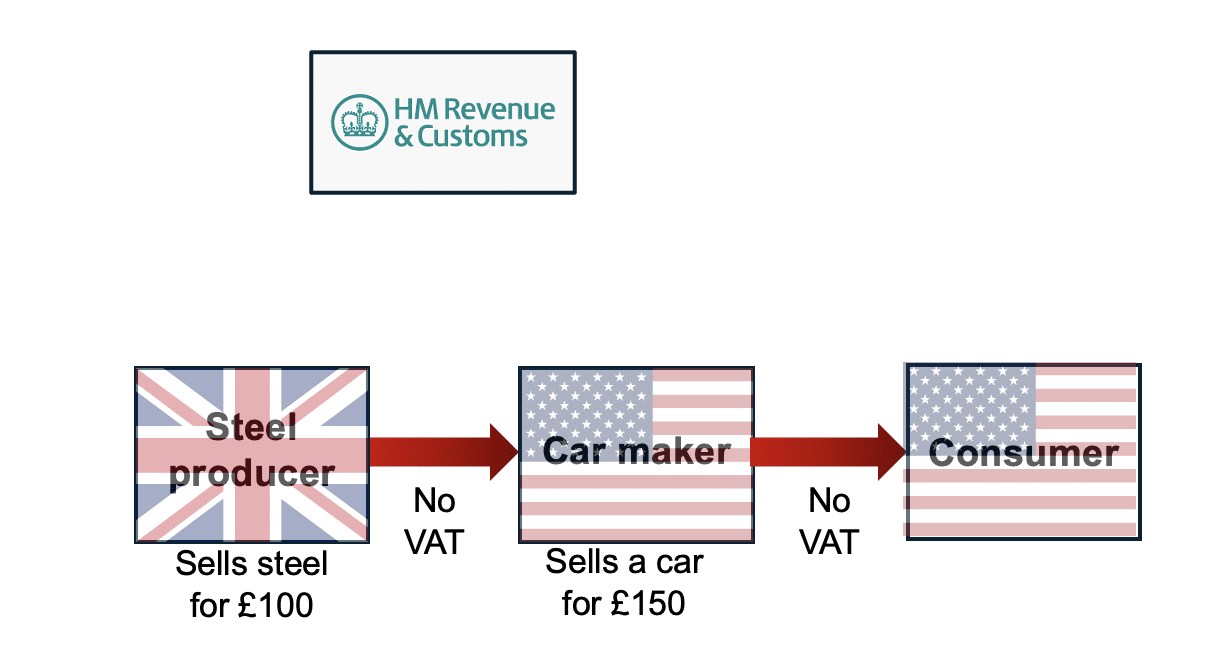

On the surface this looks like a subsidy of some kind for exports, but it really isn’t. The net result is exactly the same if it was a US car maker buying (hypothetically) British steel and selling to a US consumer:

There is no difference between the two cases.

Again, since it’s a sale to a US consumer, in some US states there would be sales tax on the final sale.

Does VAT encourage exports?

One more sophisticated argument sometimes made is that VAT is distortive because it encourages UK companies to export to non-VAT destinations (a kind of reverse export-subsidy).

There is a tax policy wonk response to this and an economist’s response to this.

The tax wonk answer is that this might be the case if the cost of VAT was borne by sellers, but when VAT is introduced (or increased), the price is added onto goods. It’s consumers who pay.9 So a seller will usually make the same profit selling into a VAT country than into a non-VAT country; and any small effects that may exist are swamped by other factors (shipping costs, marketing costs, tariffs, regulation, non-tariff barriers, contractual issues etc).

The economist’s argument is much more subtle, and concludes that VAT actually reduces exports.

Paul Krugman makes the point compellingly in this widely-cited paper. There are two separate effects, pushing in opposite directions.

First:

- Countries that adopt VAT have less income tax and corporate tax than they would otherwise have.

- VAT applies to most imports but not exports. Income tax and corporate tax apply to domestic production and exports, but (mostly) not imports.

- So higher income/corporate tax advantages imports and disadvantages exports.

- By instead having a VAT, countries like the UK are (relatively speaking) disadvantaging imports and advantaging exports.10

But a second effect goes in the opposite direction:

- The “policy wonk” position above assumes VAT applies to all products. In practice, it doesn’t.

- Major areas of expenditure aren’t subject to VAT – that means Jaffa Cakes and (somewhat more significantly) housing. So people will tend to spend more on housing and Jaffa Cakes (and other exempt and zero-rated items) and less on VATable goods and services.

- Housing is obviously not imported (nor are Jaffa Cakes). So VAT tends to reduce imports, as we buy more domestically-produced goods.

- Now the bit non-economists find counter-intuitive. The Lerner symmetry theorem (from this 1936 paper by Abba Lerner11, a foundational element in trade theory) says that, if imports are reduced, then exports are also reduced. The reason is that if we buy fewer foreign products, then foreign businesses are receiving less GBP from British importers.12 Since the world has less GBP, the value of GBP will rise, and the world will buy fewer UK products. UK exports therefore fall.13

The Krugman paper contains a rigorous analysis of both effects, and concludes that the second is stronger. Hence VAT in the real world discourages exports and imports. This is another reason why we’d all be richer if VAT applied to a wider range of products – like Jaffa Cakes.

VAT, once more, behaves nothing like a tariff.

Doesn’t VAT fund the NHS, which effectively subsidises companies?

The argument goes like this: VAT raises £170bn, which is very close to the cost of funding the NHS. In the US, with no Government funded national healthcare system, most of the cost of healthcare is paid by businesses. The fact UK businesses don’t have this cost gives them a significant advantage. Therefore the NHS, and the UK tax system generally, amounts to an export subsidy.14

The argument is, however, wrong. The US does have national funded healthcare systems (Medicare, Medicaid, and Military and VA Programs) and, whilst they don’t provide the same breadth of coverage as the NHS, they cost US taxpayers almost exactly the same (as a percent of GDP) as the NHS.

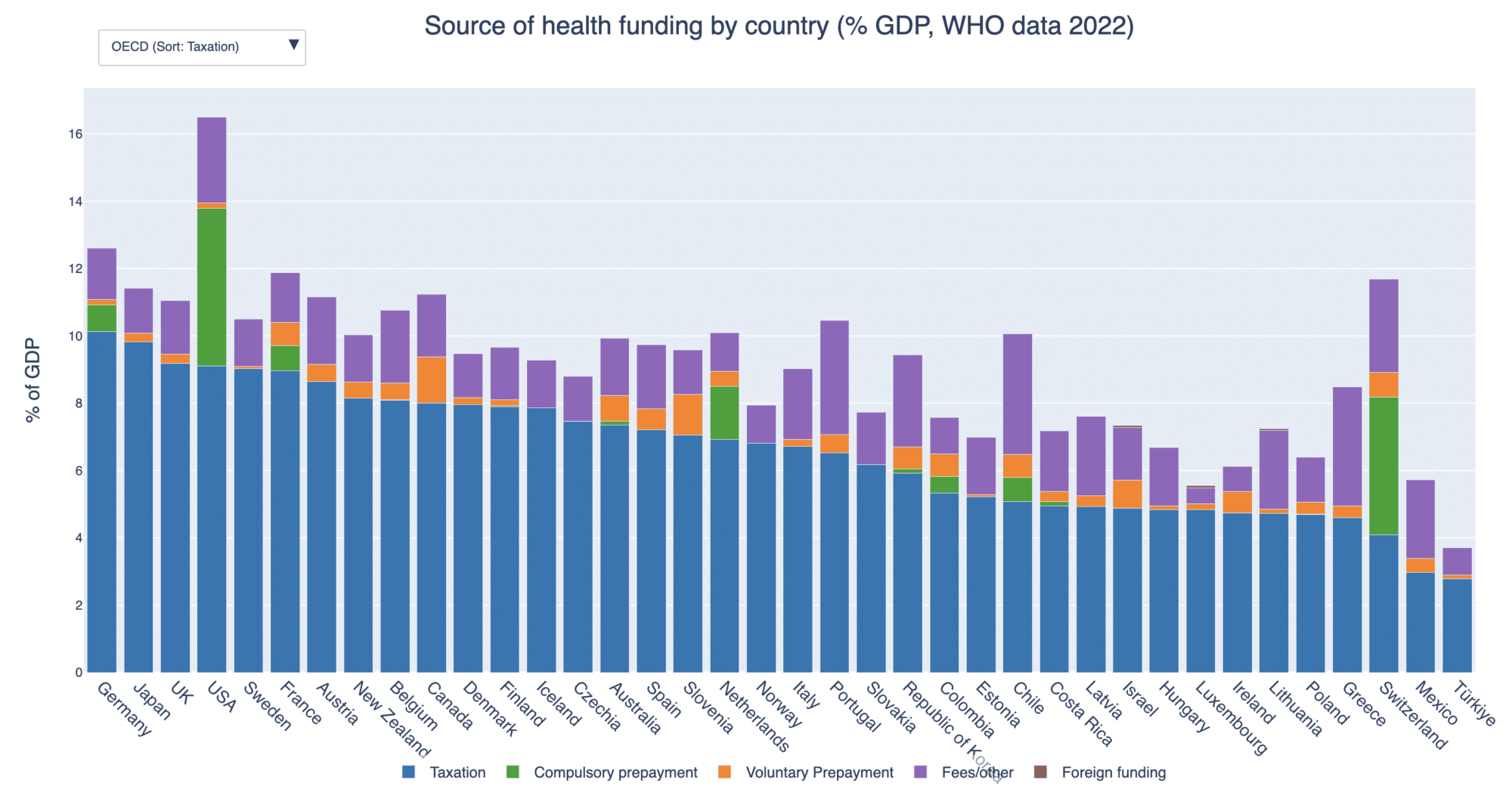

We can chart this using WHO data:

The blue bar is healthcare funded by taxation, and the UK and US (third and fourth from the left) figures are almost identical. The source for this is the World Health Organisation’s Global Health Expenditure Database.

So whilst it’s true that US companies bear much larger healthcare insurance costs than UK companies, the reason is not that the UK Government is subsidising healthcare more. The actual reasons are discussed here.

There’s an interactive version of the chart here, which lets you look at all countries (not just the OECD) and sort by total spending, as well as tax-funded spending. The “all country” chart has rather a large number countries, so to view country names you need to either zoom in or hover over a bar (and you’ll see the country name displayed).

There is an informative ONS article comparing UK healthcare spending with other countries.

The code that created the chart is available on our GitHub.

More technical arguments

There are a couple of more technical niggles.

The first is that paying import VAT is a hassle in a way that normal VAT isn’t. It’s a “non-tariff barrier”. This was a real concern during the Brexit discussions, particularly the three month delay in recovering input VAT. That led to a system of “postponed VAT accounting” which means that the cashflow cost of recovering input VAT becomes equivalent to the cost of recovering normal domestic VAT. There remain some bureaucratic annoyances with input VAT (and in countries like Italy and Spain they can be quite serious), but it’s just a small part of the overall “trade friction” – the hassle of importing goods.

Another argument goes as follows: VAT is applied to tariffs. Therefore if a US manufacturer sells a car to a UK consumer there’s a 10% tariff, and then 20% import VAT on top of that. Total VAT on the price plus the tariffs of 22%15. But a UK manufacturer selling to a UK consumer faces no tariffs – total VAT plus tariffs of 20%. Discrimination!

But on close inspection this doesn’t make much sense:

- Almost no US car manufacturer sells direct to a UK consumer. They’d sell to a UK distributor, and the distributor will recover its VAT – including the import VAT on the tariff. The same is true for most goods (and services aren’t subject to tariffs). So, in practice, non-refundable VAT applying to a tariff is a rarely seen complication.

- But even in theory, it’s not VAT that’s the problem here. VAT makes the effective rate of tariffs higher, like it makes everything higher. The problem is the tariff, not the VAT.

The United States is an outlier

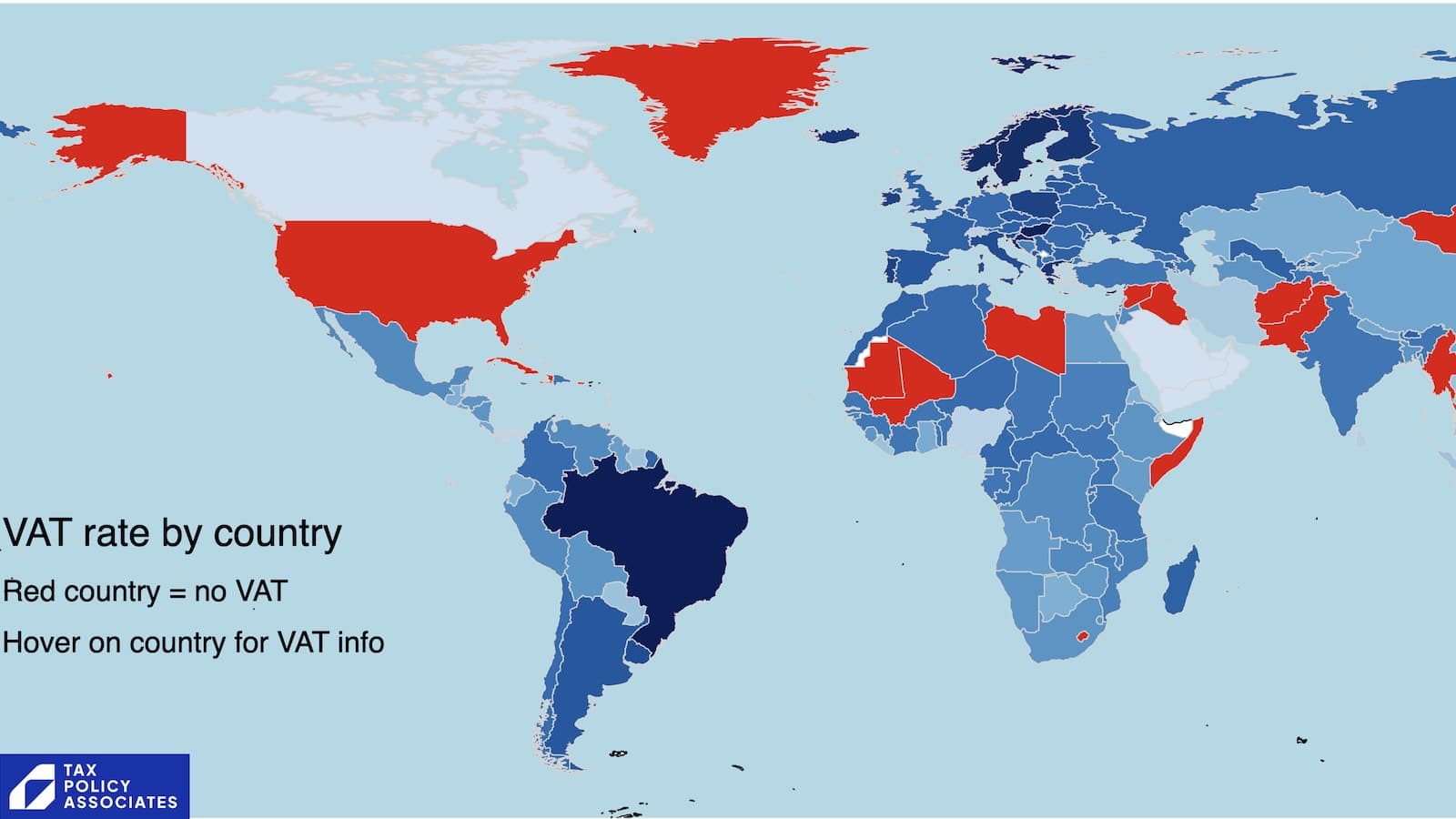

Every large developed country, and most other countries, have adopted a VAT (full screen version here):16

The most recent convert was Brazil, which had a mess of national and local sales taxes. It finally adopted VAT in 2023.

That leaves just Hong Kong, Pakistan, a few small islands and tax havens… and the United States.

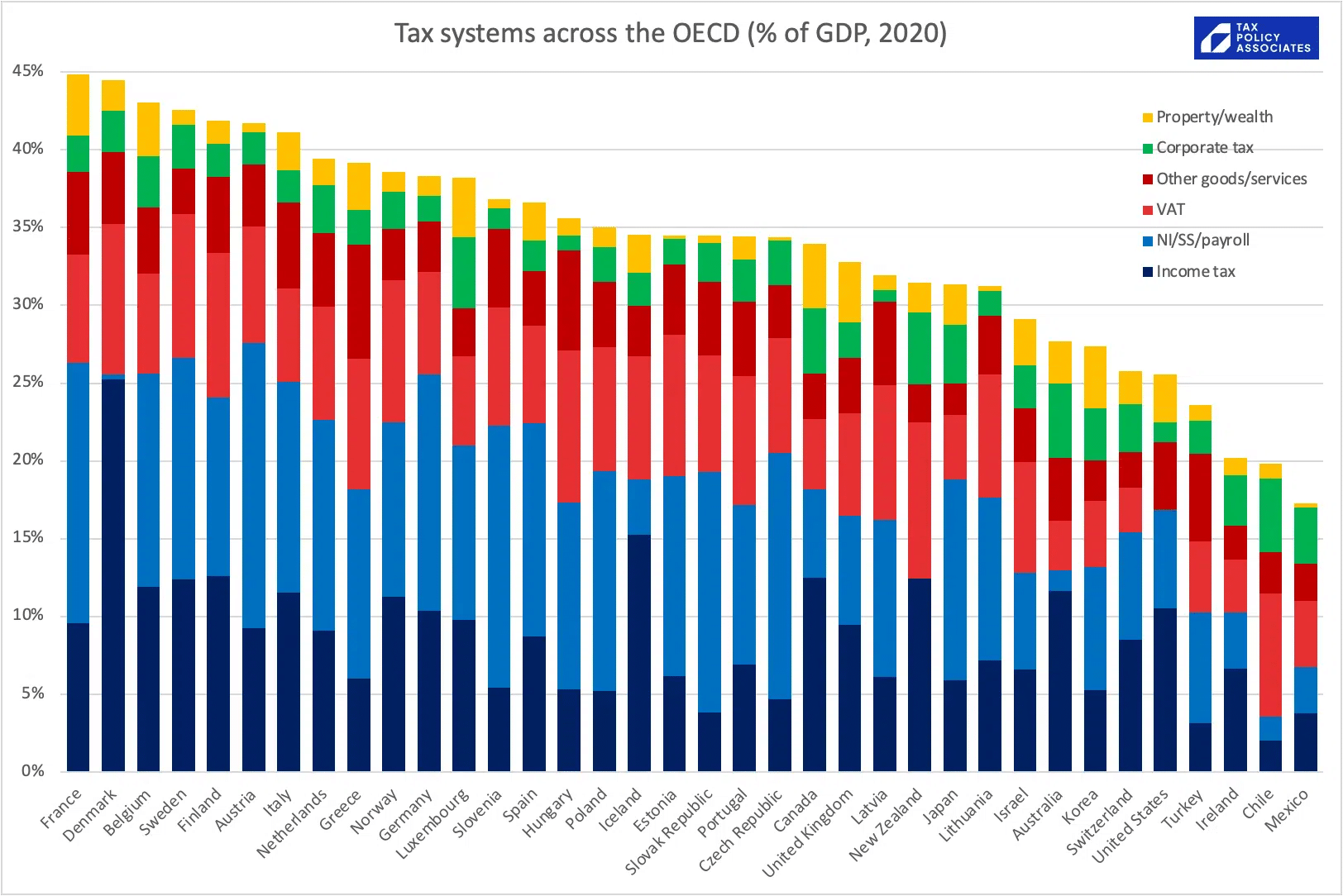

It’s often said the US is a lower tax country than the UK. That is true – and much of the difference is down to VAT:1718

There are two consequences from this.

First, no major economy could abandon VAT, as Trump seems to wish, and maintain its current level of spending. Income taxes would rise to unsustainable levels (in the UK, we’d pay, on average about 60% more income tax).

More entertainingly, it follows from Krugman’s paper that if the US kept the overall level of tax the same, but substituted VAT for some personal tax and corporate tax, and applied VAT to absolutely everything, then that would enhance the competitiveness of, and tend to increase, US exports.

I’m sure Mr Trump is working on this proposal as we speak.

Thanks to everyone whose questions online and offline sparked this article. Thanks to P and Z for their helpful discussions on trade policy and tariffs, K for VAT input, L for US State sales tax expertise, and C for an illuminating exchange on trade theory.

People occasionally ask why most of our contributors are thanked by initials, not names. It’s because they almost all work for barristers’ chambers, law firms, accounting firms or are retired HMRC officials. Whilst we’d never ask them to break any confidences, employers usually restrict public statements from their employees, and both employer and employee would sometimes be concerned about liability. So most (but not all) of our contributors choose an initial – not necessarily their actual initial.

If you have specialist tax, legal or economic expertise and would like to join our very informal panel of experts, do please get in touch.

Footnotes

The UK’s tariff website is a triumph of usability. The EU’s is awful, forcing you to read through a badly scanned capitalised page to work out the code for any particular good. ↩︎

The broad principle in all the different taxes/duties is the same, but the details are very different. That makes life complicated for an international beer company – dealing with all the different rules makes it much harder and more expensive for them to export beer than to sell domestically. But these rules aren’t tariffs. This kind of complexity is inevitable as long as different countries have different tax rules. ↩︎

Often there are one or more additional levels of local sales taxes, sometimes applying on top of the State sales tax, sometimes applying to services that aren’t subject to State sales tax, and sometimes vice versa. ↩︎

Note that, whilst all US State sales taxes are destination-based when it comes to exports to outside the US, the position is more complex for sales from one State to another. Most US State taxes are pure “destination-based” taxes, meaning that (for example) New York State doesn’t impose sales tax on a sale by a New York business to a Texan consumer. Others, like Texas, are “origin-based”, meaning that they apply on sales by a Texan business to a New York consumer – but even origin-based sales taxes don’t apply to goods exported outside the US. ↩︎

A “goods and services tax” is just another name for a VAT; I’d love to know why Australia and other countries thought it would be a good idea to create a different name for what in essence is the same tax. ↩︎

There is, however, frustratingly little evidence of the actual rate of evasion of state sales taxes, and the 5-16% figures sometimes referred to appear to be little more than informed guesses. ↩︎

That’s not quite right, but a good approximation. ↩︎

Another, shared by two US trade lawyer friends, is that Trump just loves tariffs and has no interest whatsoever in VAT. It’s a handy ex post facto justification for something he always wanted to do. ↩︎

The converse doesn’t follow; consumers won’t always benefit from VAT cuts, particularly on individual products. ↩︎

I hesitate to disagree with a Nobel laureate, but I am not convinced by this. For the reasons discussed above, VAT is actually a cost for the consumer. But let’s assume I’m dead wrong here, or missing something, and Krugman is right. ↩︎

Ironically, Lerner was a socialist, albeit a member of a now-endangered species: a market socialist. ↩︎

This also works if the goods are bought in foreign currency. The UK importer swaps GBP into that currency, and the counterparty will (often) be swapping it within someone who needs GBP, e.g. to buy British products. GBP is still leaving the country, through a more circuitous route, and reduced imports again means people outside the UK have less GBP. ↩︎

For this and other reasons, tariffs reduce exports as well as imports. ↩︎

The same broad claim is sometimes used to make another argument: that the UK and European economies can afford their national healthcare systems because their defence spending is so much smaller than US defence spending. ↩︎

i.e. 20% of £110. ↩︎

Source for the data is this table from the IMF. ↩︎

State sales tax is on the chart; it’s the dark red bar. ↩︎

Incidentally, don’t be tempted to compare the blue bars (personal tax on income) and conclude that the US level of personal taxation is about the same as the UK’s. Many US businesses, particularly small businesses, are “S Corps” – meaning that they don’t pay tax; instead, their owners pay tax as if they received the income themselves. So US corporate tax revenue appears less than it “should” be (if we could add in S Corps), and US personal income taxes appear more than they should be (if we could deduct S Corp income). A common mistake is to look at the figures for US corporate tax receipts and marvel at the low level of corporate taxation. There’s certainly truth in the proposition that US corporate tax is low, but the figures can’t be eyeballed like that. ↩︎

81 responses to “No, VAT isn’t a tariff – here’s what Trump (and others) get wrong”

VAT is simply a type of modified sales tax which the buyer, resident in the UK, pays and the seller collects and remits to the government. What makes VAT different is that each business is allowed to deduct the sales taxes they pay from the sales taxes which they collect so the net sales tax remitted is a sales tax only on the portion of value which they add. In the case of imports the UK buyer also collects the tax from themselves and remits same to the government. No VAT is assessed on exports because the buyer resides outside the UK since VAT applies only to UK residents and businesses. Donald Trump and his henchmen are stupid ignoramuses who never studied “Economics 101” and Trump is an addlepated twit with his head stuffed full of sawdust and scrambled eggs and is surrounded by “yes men” who never contradict him no matter how silly he becomes:- we all know where this will end up going:- his public-approval ratings in the USA decline daily but he’s also quite oblivious to that fact.

It’s often said the US is a lower tax country than the UK?

Can you add the american sales tax flow to the graphics.

thanks – there isn’t really a flow, just a final tax. But I’ve added some text to hopefully clarify this!

What is the main misunderstanding Donald Trump has about VAT?

The 5% for Canada isn’t entirely accurate. the 5% is the federal portion of the VAT. Province has their own PST that gets added to baseline 5%, some are 0%, some are as high as 10%

Dan maybe Trump’s team see that the seller can reclaim much of the VAT for a UK car (whereas there is no VAT reclaim for a US car), and think this is a subsidy. i.e. think that for that reason the seller can sell the UK car more cheaply.

In fact that ‘reclaimed VAT’ should equal VAT already paid further back in the supply chain.

This should logically mean that the gross price of the UK car to the seller should be higher (as it includes already incurred VAT) than the US car (no VAT incurred).

Then the seller will make a lower margin on the UK car, so all evens out.

I’ve read through your arugments. Somehow you imagine the importing country is entitled to apply VAT to a product made entirely outside of the importing company, because …

You heard it hear first. Our President has and will levy import taxes/duties/etc on a reciprocal basis to all the duties, tariffs, NGO roles, etc INCLUDING VAT levied on our exports to that country. Deal with it — or don’t trade with us. WWII ended eighty years ago. It’s well past time you paid your fair shares.

You don’t appear to have read the article. It’s no different from the various State sales taxes. Countries have a right to tax sales in their jurisdiction. If they do so to all sales, whether by a foreign or domestic seller, it’s perfectly fair.

If you expect imported goods from the US to be exempt from VAT then you are expecting, in effect, a negative tariff on US goods. You might like the idea of that but don’t pretend it is somehow fair.

And I think you’ll find, we also paid for WWII a few years ago

If you want to tax Americans on the amount of VAT collected by the UK government from Britons who import US goods then you just go right ahead and do it! It’s a silly idea but if your sill President wants to do that then so be it and we’ll see where it goes:- some people need to learn “Economic 101” the hard way and you are obviously on of those.

If the US implemented a 20% VAT tax, I assume that would be looked at as perfectly acceptable way of raising taxes, except for those that would oppose it as a flat tax. After all, 175 countries have a VAT tax.

Now, suppose we provide rebates on that tax to those products/services produced domestically

This would have the benefits of a VAT tax, plus the benefits of helping American producers. There are different administrative issues, and I assume that other countries would complain.

If Europe would announce that they will provide VAT rebates to products/services produced in Europe, would the world freak out as much as they seem to be doing now ?

in that case it’s not a normal VAT, but a tariff (under both general principles and WTO/GATS rules)

What about the following point (which I think is related to Krugman’s):

– British suppliers of VATable goods to British consumers can set their VAT inputs against the output, thus incurring no VAT burden.

– British exporters of goods to America, which are zero-rated, can reclaim their VAT inputs from HMRC. Again, no VAT burden.

– US suppliers of VATable goods to British consumers can do neither of these things, and therefore bear the VAT burden.

please read the article – I go through both scenarios in detail. British and US companies selling to the US are in the same VAT position. British and US companies selling to the UK are in the same VAT position.

You are ignoring what the government does with the funds it raises from the VAT. If it uses those to subsidize its own producers it gives them an unfair advantage over US producers. VAT is used to fund subsidized universal healthcare enabling local producers to avoid expenses – employee healthcare benefits – that US producers have to pay.

You are assuming the UK Government spends more on healthcare than the US Government. That assumption is *incorrect*. The US Government spends *almost the same*, as a % of GDP. And this is ignoring peoples’ own insurance/fees – we’re just looking at government expenditure.

See https://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/index/en

It’s a fascinating question why the US Government spends so much on healthcare, but doesn’t have universal coverage in the way almost every other developed country has. The answer to that question, however, is way outside my expertise.

Ha, ha, ha!:- more addlepated MAGA nonsense. The British NHS does not “subsidize” British companies:- it taxes them and British consumers to pay for universal healthcare services to all British people. Neither British nor American companies are obligated to subsidize healthcare for employees and most do not and virtually none subsidize heaalthcare for the general public. Mr MAGA-man, you need to get your head out of your own fanny and try smelling someone else’s “raspberries” (per the “Khrushchev Principle of Raspberries”)!

It’s also helpful that for the accountants – i.e. the people applying accounting standards to work out an objective and agreed measure of the profits made by companies – the overall profit for each of the companies in each of the examples arising from the flows shown is exactly the same. The P&L/income statements are entirely unaffected by the location of the businesses or the consumers.

It’s another natural consequence of VAT, whilst involving somewhat complicated flows to and from HMRC, ultimately not in substance representing a tax (and indeed subsidy) on businesses.

The Republic of Ireland charge the US companies a much lower corporate tax rate than the recommended EU rate. How do they continue to get away with it? The US businesses benefit from this, as well as transferring their profits to the US where their tax rate is lower. Are my impressions the reality? If so, how should this be addressed?

Ireland charges the OECD agreed minimum tax rate which the US agreed to and subsequently repudiated. Profit shifting by US corporations is an issue for the US govt to police, not Ireland or the EU alone. In any case, the EU has no jurisdiction over Irish taxation rates (read the Lisbon Treaty). It does, via the ECJ, over competition in the single market and can, and in the case of Apple has, ruled against what it decided (on appeal) was a tax ruling that amounted to a subsidy.

I think the reality is that the USA has to sort their massive deficit, the balance of trade. I checked and the Chinese surplus is $1 trillion. This has been a bigger issue since the early 1990’s, when Chinese dumping became an issue when they decided a new strategy to grow including in low value imports.

We are all economically and emotionally tied to cheap Chinese goods, many copies of others, when we know how the goods are made cheaply but leave those concerns aside, because it’s cheap and fast. The US I suspect has paid a very heavy price. Their $800 deminimis (subject of the other exec order the other day to remove) was like an open goal!

On the other hand, the whole world is emotionally and economically tied to US services by the big 4, Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft and Apple. Most countries are imposing taxes such as DST to redress this, but fail to see that in goods, there is an imbalance in treatment as far as the USA. Whether right, that’s what they think. This niggles this administration along with the imbalance in defence spending which the US has gone in hock to pay for.

The result here I am sure after the big gestures will be deals that redress these imbalances.

Surely the point Trump makes is that when a US citizen buys a UK made car they pay just 2.5% to the US treasury.

But, when a UK citizen buys a US made car, the UK Treasury gets 10% tariff, compounded by a 20% VAT, and in many cases as this now pushes the price above £40k, a basic and an enhanced level of car tax, about 8% enhanced. So perhaps a total revenue of circa 40%.

Is that the way to treat our US ‘allies’!

I’m sorry, but this is just stupid. When a UK citizen buys a car made in Middlesborough, VAT is charged. So, obviously, when a UK citizen buys a car made in Michigan, VAT will be charged. And then cars are subject to car tax, wherever they’re made. How can anyone think it would work a different way?

As for tariffs, negotiating them down is what trade agreements are for. The UK could give up its 10% tariffs on US cars. And the US could give up its own tariffs on cars, which vary from 2.5% to 25%.

I think the point Barry was making was the taxes in total for the same priced car, but I think sales tax plays a part. I don’t think the ‘stupid’ comment was justified personally.

Could even be a US company with a plant in Europe selling home.

Say $20k for each car, the base price before any taxes.

In the UK, we export zero rated and so on landing in the US, there would be import duty of 2.5%, so $500 tax, total price $20,500 to a dealer. Obvioulsy they will mark up, so say 25% mark up. Sales price, before sales tax of £25,625. Lets say sales tax of 4% ($1025)assuming a New York sale. It would be 9.75% in LA. So I make that a consumer gross price of £26,650

The same in reverse. A US plant sells a $20,000 car to a UK dealer. On Import there would be $2000 duty so a base price of $22,000. There is no VAT cost as the dealer uses postponed accounting and so the VAT is never ‘paid’.

That dealer also applies a 25% mark up. That makes his price before tax $27,500. The consumer pays 20% VAT ($5500) so a total price for the same car of $33,000 Ignoring any extra registration and emission taxes either side of the Atlantic.

So the difference is $33,000 -$26,650 or $6350 or about 23%. And the UK is WAY more heavy on other taxes including income taxes.

Doesn’t sound so stupid now?

People in different countries pay different taxes. That’s not a tariff and not discrimination. The question is whether a car *sold from* one country is taxed more than a car *sold from* another.

It isn’t.

Unless you believe all countries should have the same tax. Which surely you don’t. So I do think it is a stupid comparison, which misses the point entirely.

Ignore taxes, the US believes that there is an extra ‘cost’ of US firms doing business selling goods to others than it earns the other way. And more specifically those other countries expect the US to still be the World protector, without paying for it. And a myriad other niggles. A better policy may be for the EU/UK to lower tariffs to the US levels but agree on numbers to stop duming, either way.

The example I gave was crystal clear. Yes there will be extra taxes such as emissions charges, currency differences, but for the same thing, it will cost more when selling that thing in the UK. That cannot be denied I think.

As to how to solve this, negotiation I think, which yesterday was ALL ABOUT, because the US has to stop the current problem. This has ben an issue for decades.

The tactic is, go high and get concessions. The World is a boardroom, that’s how Trump sees things, and he also believes he has a card that noone else can play, World defence. Ignore what politicians are saying, look at what they do.

Of course the US has a trade surplus with the UK.

When a Briton buys a US car they pay 10% import tariff plus 20% VAT. When they buy a UK car they pay only the 20% VAT but no import tariff so how does the VAT “compound” the tariff on imported cars? Pls take the time to study “Economics 101” plus learn to do some basic arithmetic and accounting. Donald Trump is a failed real-estate developer who inherited all his wealth from his father and mainly he failed because he cannot add “1” and “1” to make “2” and his supporters all seem to have the same problem.

The argument that most countries have VAT just proves that most countries have politicians that don’t care about fleecing their citizens. It’s harder to put a scam like at across the citizens in the US because the democracy is much more effective than in socialist countries.

Why do I insist on calling VAT a scam? Because I remember the day it came into effect in the UK. Suddenly, not only my salary but also my bank account was worth 15% less than the day before. The govt had just reached it’s grasping hand in and taken out 15%. That’s why they will never get away with such a scam in the US. Americans are more money-savvy and protective of their hard-earned money.

The total level of tax didn’t change when VAT came in. The mess of old sales taxes were replaced by VAT (at 10%); the revenue was the same. You can see the data on this here: https://taxpolicy.org.uk/2022/10/11/uk-tax-system-in-five-infographics/. Successive Conservative governments put up the rate of VAT to either cut income tax (Thatcher) or avoid increasing income tax (Major, Cameron).

The idea that the UK, Singapore, Australia, Canada etc are “socialist” is very silly. The idea that VAT is “socialist” is also deeply silly – historically it’s been far more popular with parties of the Right than those of the Left.

I’m not posting your other comments about Nazis, because this is a website about tax. Other forums are available for political rants.

I have worked in VAT for over 37 years and even I am amazed that people have ‘bought’ the concept that the same sum can be passed around in most cases as often it only matters when the final sale is made, like sales tax. But no, it doesn’t all flow round in a circle, a great whopping chunk of it disappears because of fraud and the fact the system is almost sitting up and begging to encourage theft. Either the designers were idealists or crooks in on the deal and have been cashing in ever since. It’s hard to way which applies. Scams, cheats can be read about back to Persian and before times, so none of this is ‘new’.

I think the US is right not to copy the European model on VAT, but maybe a hybrid approach would work

I’m sorry but the evidence is dead against you: sales tax is much more prone to fraud, which is why only one developed country has it, and 170 countries have VAT.

What evidence? If a previous correspondent was right, the 170 may have realised it’s a great way to fleece people without it being that obvious. The UK got along perfectly OK with other systems. I have also worked in New Zealand which has a GST but applies it in a much smarter way.

Most actual authorities on VAT don’t assume that they, as an outlier, are in the wrong.I suggest you read this paper by the very eminent Rita de La Feria and Richard Krever, who suggests the opposite, that their Modern VAT system is likely the future.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/288287173.pdf

I am never afraid of being an outlier, rather than a ‘Sheep’. I do sometimes feel we tend to ‘play the man, not the ball’, to somewhat quote the other best source of business and political strategy, Yes Minister and Yes Prime Minister, still sooooo accurate.

The man in this case is clearly often wrong, as have other World Leaders been on occasion, but there may be something in what he says, about the cost of doing business. Am in no way a supporter, but these things need debate, not insults, in my opinion.

The big difference between the New Zealand GST and UK VAT is that the New Zealand base is wider, so the rate is lower *and* it raises more, as a % of GDP. The data is here https://taxpolicy.org.uk/2022/10/11/uk-tax-system-in-five-infographics/ . Rita talked about the New Zealand case on the show. You may have misread Rita and Richard’s paper?

VAT isn’t really responsible for “fleecing”. The data shows that the overall indirect tax take as a % of GDP didn’t change materially when VAT was introduced; it was just a shift from inefficient and confused sales taxes to VAT. The data is at the same link as above.

In a parallel universe where VAT never happened, the UK would still tax more than the US, and the French even more – but they’d do it with a mess of different sales taxes/duties instead (much like Brazil used to, before Rita helped persuade them to move to VAT).

Why doesnt uk abolish VAT on imports as it does on exports. That would remove Trump’s argument. UK can do this as it is no longer bound by EU rules.

so there’s 20% VAT on a UK manufacturer selling a car to a UK consumer, but no VAT on a US manufacturer selling a car to a UK consumer.

Are you sure about this?

This is arrant nonsense. I recommend you inform yourself about why VAT was created in the first place. Besides the advantages articulated in the article it also facilitates cross border trade and economic integration. It’s a large part of what makes the EU single market work. I recommend “A Short History of Brexit” by Prof Kevin O’Rourke for a clear explanation of it. It’s something I hadn’t fully appreciated before reading the book.

Amazed to see on the chart that Ireland tax take is c20% of GDP, while UK c33% and France c45%.

Quick check on google and see the figures are similar to those given by the OECD.

How does Ireland keep it’s tax rate so low. No defence spending to speak of but ….

unfortunately the golden rule of international statistics is: never take seriously any figure calculated using Irish GDP. The problem is that Irish GDP is artificially swelled by [US multinationals using it as a hub][tax avoidance] (delete according to your preference). The small size of the country means that this has a huge effect.

Think there is a typo here:

Therefore if a UK manufacturer sells a car to a UK consumer there’s a 10% tariff, and then 20% import VAT on top of that. Total VAT plus tariffs of 22%.

Should it not be a ‘USA manufacturer’

ps: enjoying R4 more than usual

oh dear. Sorry!

Is there a typo here?…Therefore if a UK manufacturer sells a car to a UK consumer there’s a 10% tariff, and then 20% import VAT on top of that. Total VAT plus tariffs of 22%. But a UK manufacturer selling to a UK consumer faces no tariffs – total VAT plus tariffs of 20%. Discrimination!

apologies – was a typo. Now fixed!

I can see why each contributor to the manufacture of a product paying VAT reduces the probability of tax evasion (although I wonder how much all that accounting costs!), but is it fair that the end consumer ends up paying the full 20% rather than just the “value added” part of the final transaction?

The whole point is to tax 20% of the price for the consumer.

If it worked as you suggest then it would collect a lot less but, more importantly, would be super-easy to avoid. I just make sure the final company in the supply chain makes almost no profit. Ta da: no VAT.

Is it not the case that ‘sales taxes’ are generally applied only to physical goods being sold whereas VAT applies to both goods and services? (Hence its alternative name.)

OMG the rules on US State taxes and services are a mess. I don’t pretend to understand them, but it’s certainly not that services aren’t taxed…

As it usually happens in economics, to really say if A is B or not, you need to specify what is fixed and what is not.

In this instance, consider a country with a universal 25% origin based sales tax. This is obviously a purely internal measure and not a concern for other countries. Now let’s add to this sales tax a 25% import tariff and a 20% export subsidy. Now we have something identical to a 25% VAT, up to the collection mechanism.

This means that while VAT is not a tariff, it is equivalent to something purely internal plus a tariff plus an export subsidy.

sure, and an economist would say that the (very theoretical) combination overall doesn’t behave like a tariff. Interestingly, trade law/WTO doesn’t do that, and so whilst VAT is permitted by WTO/GATS, the combination taxes would not be.

Whilst no country could abandon VAT 7(unless of course it replaced it with a sales tax) the UK has missed a trick here. In return for a trade agreement with the US it could abolish Import VAT on imports by US companies. That would cost absolutely nothing as the VAT fwould be collected further down the chain because there would be no import VAT to deduct

One practical objection to this is that people will order goods directly from the US and save VAT. Certainly small valuable goods like iphones.

The legal objection is that our VAT system would then be discriminatory and contrary to WTO/GATS (which I suppose we still care about).

And it obviously makes no difference to other cases where there is an importing business, and so it’s just smoke and mirrors. If Trump cares about the actual effect then this wouldn’t placate him.

But the real answer is surely that Trump has no interest in the actual effect of VAT.

Politicians like Trump have a real skill in being ‘prefessionally ignorant’, in order to force change. He sees tariffs as tools to induce concessions, not without good reason given what we see (the UK apparently offering to ease isues for US tech firms).

Don’t imagine that the well discussed belief in many of the US administration that Europeans are freeloaders on Global defence won’t become part of these levers. Some would argue the US spend on defence is greatly supported by debt, when some woould argue that all should ‘chip in’. The tariff threats can help with that. The tactic of threat, opponent weakens, obtain result then tariff eased/abandoned is a clear power play tactic from a master negotiator. We need to learn not to blink first in my view. And if all else fail, invoke the Charlie Croker defence

“”You’ll be making a grave error if you harm us. There are a quarter of a million American businesses in Britain and they’ll be made to suffer. Every McDonalds, Dunkin Donuts, Starbucks, KFC and Amazon hub in London, Liverpool and Glasgow – will be smashed. Mr. Starmer will drive them into the sea”

Seriously, of course he knows that VAT is not a tariff, but what it is is a HASSLE in compliance, when almost always with B2B the effect is zero.

I always considered that the USA has a deep seated suspicion that VAT is a Socialist tax, considering the European origins (forgetting the actual origin which seems more local). I am a VAT specialist and even I think it’s dumb to have a set of rules that passes the same amount of money round in a loop, but that indeed is the way that our Franco/German inspired tax works in many cases. You have to be suspicious if you are of a certain mindset of a bureaucracy in Europe that set this up, just after the war and contibues to think its a good idea.

But what is often forgotten is how mind cruishingly complex US Sales tax are, in practice. My understanding is that the equivalent of an exemption certificate to avoid the cumalitive effect of sales tax, especially for inter-state movments is needed and each state has individual sales tax rules. I have been a VAT expert for over 35 years and even I glaze over when US sales tax administration is discussed.

I actually think the UK’s initial response to all this was right, see what they DO, not what they SAY. I heard quote too recently by the US Vice President who said tht the administrtion cared little on what leaders said in public, it’s what they say in private that matters. Public comment is often what people want to or expect to hear. I think he is bang on the money generally with that thinking.

Form: The reason could have been anything and Trump’s chosen VAT. Whether it stacks up or not seems irrelevant because…

Substance: Trump wants an external revenue service collecting taxes through tariffs so he can cut income tax for Americans.

Try telling this to the Donald. What I think he may be getting at is the VAT levied on sales of US sourced product in VAT countries where the rate is much higher than domestic sales taxes in the USA and he sees that as discriminatory as for instance EU manufacturers have to apply double digit tax rates to sales domestically, whereas those same goods sold in the USA are only taxed at single figures. That is of course nothing to do with tariffs, but the average US citizen is not going to be given the above explanation.

Great post. I have been fascinated by VAT since becoming self-employed (and VAT registered) 20 years ago. It’s the world’s most counter-intuitive tax.

The interactive map is great too. Maybe do something similar for VAT registration thresholds. There’s a whole other post in that! Keep up the good nerdy work.

This is the kind of in-depth anaysis that BBC Radio 4 should be broadcasting to enlighten us all

Excellent article. But how can you deal with with stupidity and those who refuse or cannot be educated?

Hi Dan, not sure I entirely agree with your comment ‘So, for example, the UK imposes a 10% duty1 on importing most types of car. A British car manufacturer doesn’t pay this; a foreign car manufacturer exporting to the UK will have to pay’

Obligation to pay import duties is set by the incoterms agreed when the contract is signed. Generally, the importer and not the exporter will be liable to import duties, unless the incoterm is DDP

thanks. That was very sloppily worded, and is now fixed.

If a Chevrolet is sold in Germany the consumer pays import duty plus VAT.

If a BMW is sold in America, the consumer pays import duty but there is no VAT to pay. HOWEVER the manufacturer claims back the German VAT.

That is a 20% export SUBSIDY.

the article explains why that’s not correct.

You should compare similar processes:

If a Chevrolet worth 20,000 USD is sold from America to Germany the consumer in Germany pays import duty plus VAT (20,000 plus 10% duty plus 19% VAT = 26,180 USD).

If a BMW worth 20,000 USD is sold within Germany the consumer pays VAT (20,000 plus 19% VAT = 23,800 USD).

The consumer in Germany has to pay the same VAT whether it’s an imported or domestic car.

(assuming that the above example is a direct sale to a consumer in Germany, but the principle is the same if you add importers, car dealers etc.)

Your second sentence: ‘If a BMW is sold in America, the consumer pays import duty but there is no VAT to pay. HOWEVER the manufacturer claims back the German VAT.’

The German/European manufacturer can only claim back VAT it has paid to its suppliers. As it hasn’t received or invoiced VAT to the American consumer there is no recovering any VAT from that. VAT for companies is only a “transitory item”, i.e. it does not affect costs or profits. The exception are very small companies exempted from VAT. They cannot charge VAT, but the VAT they have to pay their suppliers does indeed reduce their profits as it cannot be claimed back.

As a small translation company in Germany we pay VAT to our suppliers and receive VAT from our clients. The VAT received from clients is reduced by the VAT paid to suppliers.

What your president actually wants – no VAT on cars from America – would mean a heavy 19% subsidy for American manufacturers to the detriment of German/European manufacturers.

The unwanted side effect with all these aggressive (non-reciprocal) tariffs is that in the end nobody will want to buy American products and services any longer. The development in Canada and Denmark of people boykotting American products and substituting them will quickly spread world-wide.

“Why does Trump think VAT is a tariff?” He probably doesn’t. If not, one hopes that at least his advisors will have told him that it isn’t. Regardless, it is politically expedient for him to claim that it is.

Thanks Dan (plus all those assorted helpful initials), illuminating article.

A potential error in the line: “ Therefore if a UK manufacturer sells a car to a UK consumer there’s a 10% tariff, and then 20% import VAT on top of that.”

I also thought this – the manufacturer is US not UK

Then following sentence puts total tariff + VAT at 22% when I understood that to be justbyhe VAT, with sum total 32%

I believe the Canary Islands (part of Spain) have no VAT.

Canary Islands have an IGIC, lower rate, more reliefs, but the same approach. I once dealt with a case where UK VAT man was asking for VAT but the same transactions had suffered IGIC in the Canaries.

“Therefore if a UK manufacturer sells a car to a UK consumer there’s a 10% tariff, and then 20% import VAT on top of that. Total VAT plus tariffs of 22%”

Did you mean 32%, not 22%?

badly worded! Should have said “total VAT on the price plus the tariff of 22%”. I’ll correct!

Well done, Dan. Do you not have a contact in the USA who can read your excellent article and explain it to the USA president and most of our MPs?

Another funny part of the US Sales Tax regime is that most states have an equivalent Use Tax where consumers are expected to declare and pay tax on any purchases made outside of the state but used within the state.

Of course in practice nobody does this and it’s almost impossible to police (with the exception of cars which are easy to catch when you register them with the DMV). This is why many states have passed laws to make the internet shopping services account for sales tax when shipping into their state.

Thanks, Dan – a very helpful article.

I had assumed the argument was based on the fact that a UK company can set output VAT against input VAT whereas a US company can’t, and that this was considered “unfair”?

see the article – a US company has no input VAT (even if it buys from a UK supplier).

Dan – I agree the UK now has PVA for import VAT which makes things a lot simpler than the days of deferred VAT and having to have deferment bonds to cover any duty due. However you still need to VAT register in the UK. In the EU however, the reclaim of import VAT is made very difficult, in particular in Spain and Italy. You also have to VAT register in each country separately and file returns. Possibly incorporate also. So I can see where the US is coming from. Thanks

That would justify a focussed complaint about the non-tariff barriers caused by VAT registration and reclaim formalities. There is no sign Trump is remotely interested in that.

If the VAT isn’t a cross border trade issue why does the EU insist on a “harmonised” VAT rate across all it’s member countries? Because in the words of the EU themselves ‘to avoid distortion of competition'”

It doesn’t. The framework is harmonised, the rate is not. It is the framework that facilitates the single market (explained much better than I could, in another comment on this article).