Barrowman’s notorious PPE contract was in the name of PPE Medpro Limited, a UK company. The company has a “shadow” – there’s an identically named Isle of Man company controlled by Barrowman. This is highly unusual – and we’ve found six other Barrowman businesses with identically named offshore “shadow companies”. In one case, involving Barrowman’s Smartpay business, there’s evidence that the “shadow” was used to trick third parties into thinking that they were dealing with a UK company, when they were actually contracting with an offshore company. And Smartpay admitted to a tax tribunal that this was the purpose of the arrangement. We believe there are grounds for a criminal investigation into whether Smartpay committed fraud.

And this all raises the question whether PPE Medpro used a similar tactic to trick the Government into thinking they were dealing with a UK company, when they were actually contracting with an offshore company. That could explain how the £65m profit from the sale of PPE to the Government ended up untaxed and offshore. Barrowman doesn’t deny the Smartpay “trick”, but does deny misleading the Government.

In this report:

The shadow companies

We can identify seven “shadow companies” – offshore companies which duplicate the names of other, mostly UK, companies:

- PPE Medpro Limited is the name of both a UK company and an Isle of Man company.1

- Smartpay Limited2, which participated in the loan tax avoidance schemes, is the name of both a UK company and an Isle of Man company.3 Both Smartpay companies were found by a tax tribunal to have unlawfully failed to notify HMRC of a tax avoidance scheme.

- SP Management Limited, which also participated in the loan schemes, is the name of both a Maltese company4 and an Isle of Man company.5

- Carnegie Knox Limited, an accounting firm6 is the name of both a UK company and an Isle of Man company.7

- Vanquish Options Limited, which created the doomed avoidance scheme intended to escape the loan charge, is the name of both a UK company and a Maltese company.8

- Knox Private Office Limited, which “sits at the heart of the Knox Group of companies“, is the name of both a UK company9 and an Isle of Man company.

- Gateway Outsource Solutions Limited, which also runs a contractor umbrella, is the name of both a UK company and a Maltese company. The UK company is controlled by Paul Ruocco, who has extensive Barrowman connections. It previously (and unlawfully) listed an Isle of Man company, Panda Holdings Limited, as the person who controls it. Panda Holdings is registered to the Knox Group’s Samuel Harris House address and is owned by Knox Limited. Timothy Eve (the Deputy Chairman of Knox, Barrowman’s business) is a director. The Maltese company is run by Timothy Blackburn10, who appears to run all of Barrowman’s Maltese entities.

Very likely there are more.111213

Why create shadow companies?

This won’t be tax planning or tax avoidance, for the simple reason that tax rules don’t care about company names. It isn’t brand/name protection,14 because the UK companies are active, not dormant. It’s not to serve Isle of Man customers rather than UK customers, because the solutions sold by these companies are, we believe, very focused on the UK, and (excepting PPE Medpro) UK tax avoidance.15

Our team can’t recall seeing legitimate businesses with identically named companies incorporated in different jurisdictions.

The reason is obvious: the potential for error.16 For this reason, businesses much larger than Barrowman’s, with very complex group structures, don’t duplicate names.17

So, when normal companies go out of their way to avoid even similar company names, why does Barrowman’s group do the opposite, and deliberately create “shadow companies”?

There’s one obvious answer: to trick people into thinking they’re dealing with a UK company, when they’re actually dealing with an offshore company. This isn’t speculation: we have evidence of Smartpay doing exactly this. And Smartpay has admitted it.

The evidence of fraud by Smartpay

In September 2015, Jane18 secured a contract through a recruitment agency, and decided to use Smartpay as her umbrella company. This turned out to be a bad mistake, because Smartpay embroiled Jane in a tax avoidance scheme which may have been a fraud on Jane and HMRC, and ended up costing Jane a large amount of money. This report, however, focuses on a entirely separate issue.

The idea behind “umbrella companies” is that employment agencies don’t want to take on employees, but individual contractors don’t want to be self-employed (given the complications of “IR35”). So both essentially farm this out to an “umbrella company”. The umbrella company has lots of individuals on its books, including Jane. When Jane found a job through a recruitment company, Fuel Recruitment, they engaged the umbrella, and the umbrella employed Jane.19

Smartpay had a dilemma:

- They really wanted to be an Isle of Man incorporated and tax resident company. Then they wouldn’t pay tax on their corporate profits, wouldn’t have to publish accounts, and could engineer tax avoidance schemes that both technically and practically were harder for HMRC to challenge.

- On the other hand, Fuel Recruitment and other recruitment agencies insisted that umbrellas were UK companies. By 2015 there was widespread suspicion of umbrella companies, and the legal and reputational risks they created, and it had become market practice to require assurance that the umbrella was a UK company in the form of a “compliance pack”.

Smartpay chose to resolve this with a “bait and switch”. Their Isle of Man company, Smartpay Consulting Limited changed its name to Smartpay Limited on 27 April 2015. It was this Smartpay Limited that engaged Jane as an employee. The UK Smartpay Limited would give Fuel Recruitment the compliance certificate as if it was the employer. That wasn’t true.

Here’s the evidence:

The Isle of Man Smartpay Limited hires Jane:

Smartpay communicated with Jane from a smartpaylimited.co.uk email address – and https://smartpaylimited.co.uk showed Smartpay Limited as a UK company.

Jane didn’t notice, but when Smartpay sent her their application form, the company’s registered office (shown at the bottom of each page) was in the Isle of Man:

And when she signed an employment contract, she didn’t notice that her legal employer would be Smartpay Limited, an Isle of Man company:

The UK Smartpay Limited provides the compliance pack

Fuel Recruitment, Jane’s recruitment agency, then asked Smartpay for its “compliance pack”.20

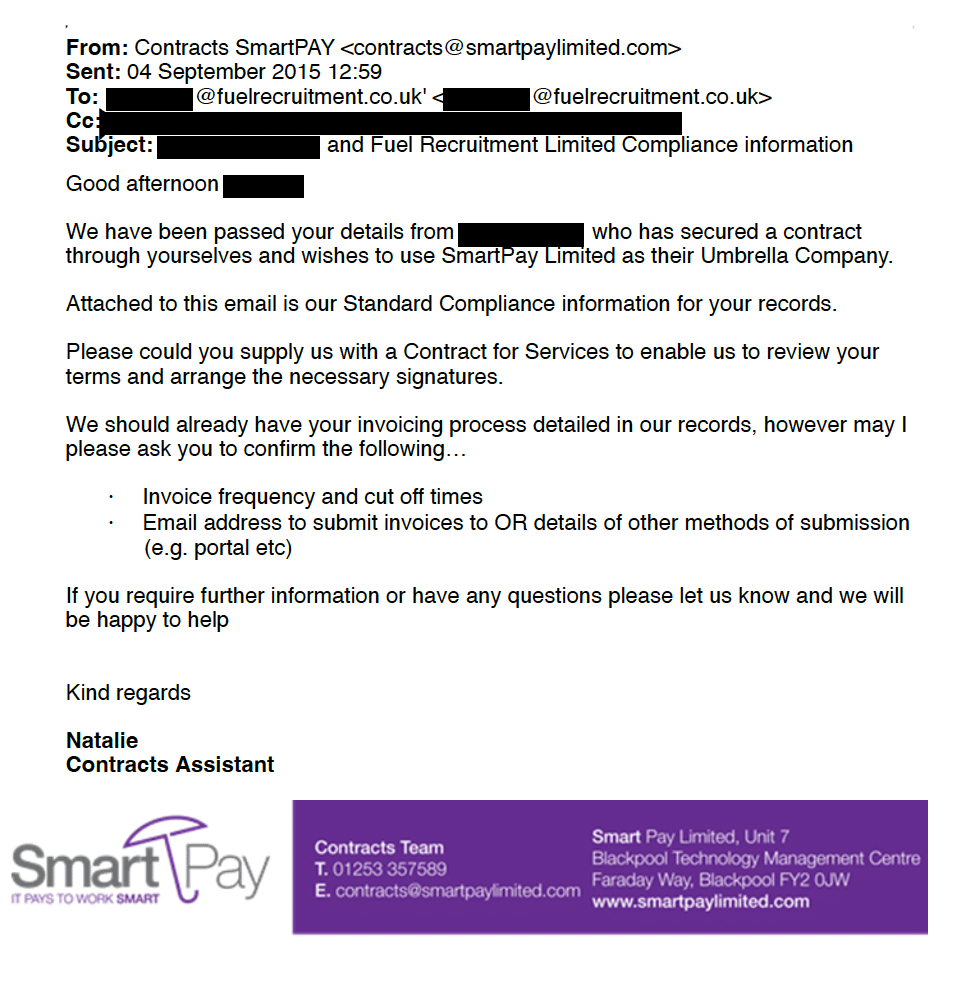

So Smartpay sent out this email to Fuel Recruitment:

The email came from smartpaylimited.com, which was (and is) the website of the UK Smartpay Limited.21 Note the footer at the bottom, showing the Blackpool registered address of Smartpay Limited, the UK incorporated company.22

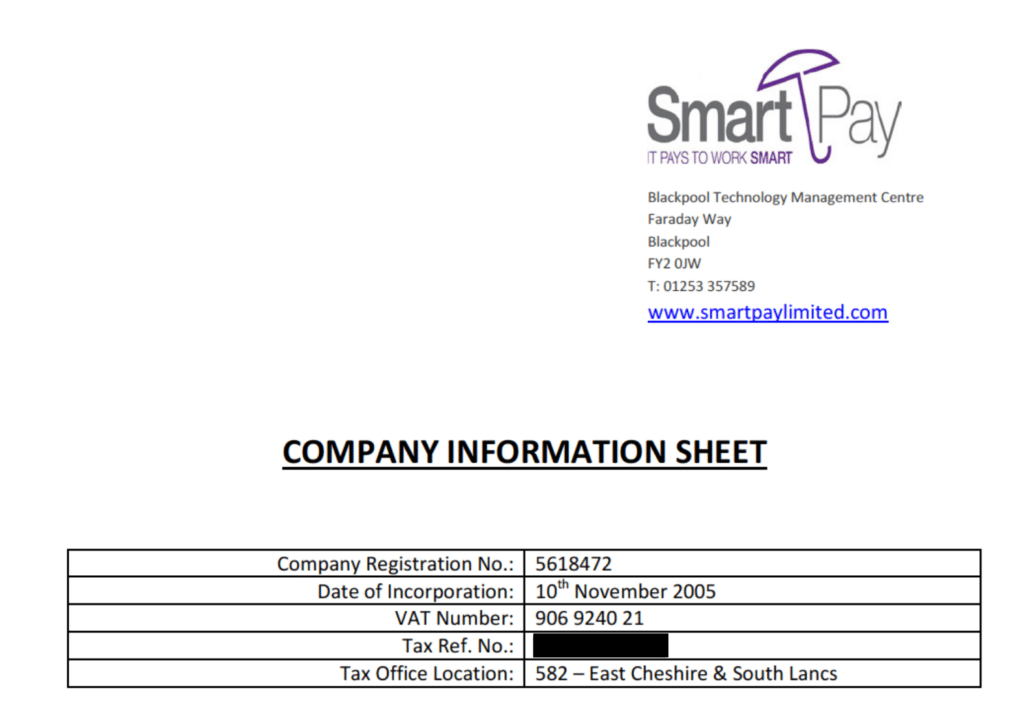

Jane was definitely employed by the Isle of Man Smartpay Limited. But in that email, the UK Smartpay Limited was claiming to be the employer. Here’s the company information they provided to Fuel Recruitment:

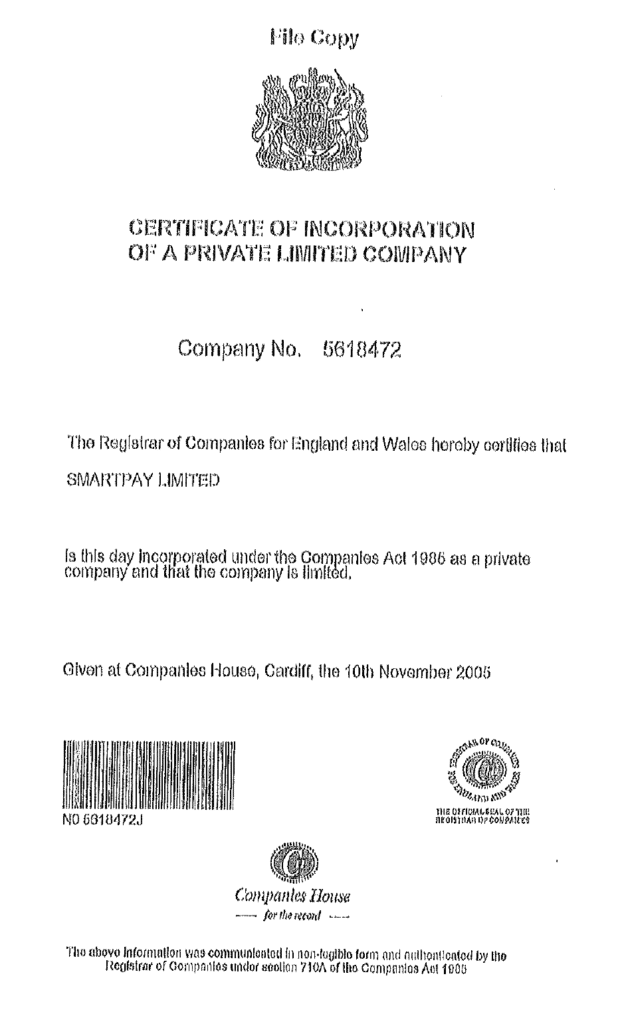

They then provided a (poor quality) scan of the UK company’s certificate of incorporation:

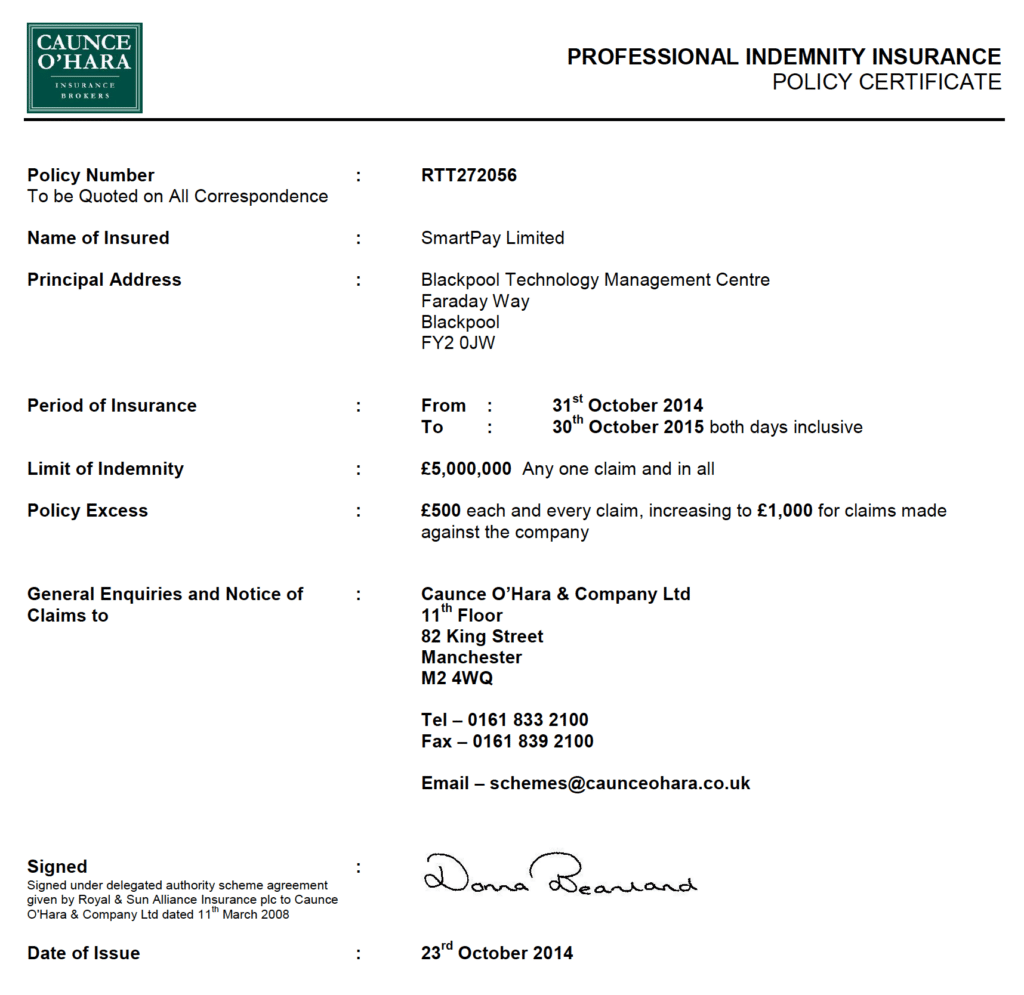

The professional indemnity insurance certificate provided was for the UK company:

The “compliance pack” was therefore a false representation – a claim that the employer was a UK company when it was not.23

The metadata to Smartpay’s standard compliance pack indicates it was prepared by John Hardman, the former solicitor, struck off for dishonesty, who acts as Barrowman’s legal adviser.24

The Smartpay admission

This wasn’t a one-off – it was in fact Smartpay’s standard practice. That has been confirmed, surprisingly, by Smartpay itself.

Like other Barrowman companies, the two Smartpay Limited entities unlawfully failed to notify HMRC that they were promoting a tax avoidance scheme.25 HMRC took this to a tax tribunal, which reached the same conclusions as other tribunals had for the other Barrowman companies: the failure to notify was unlawful.

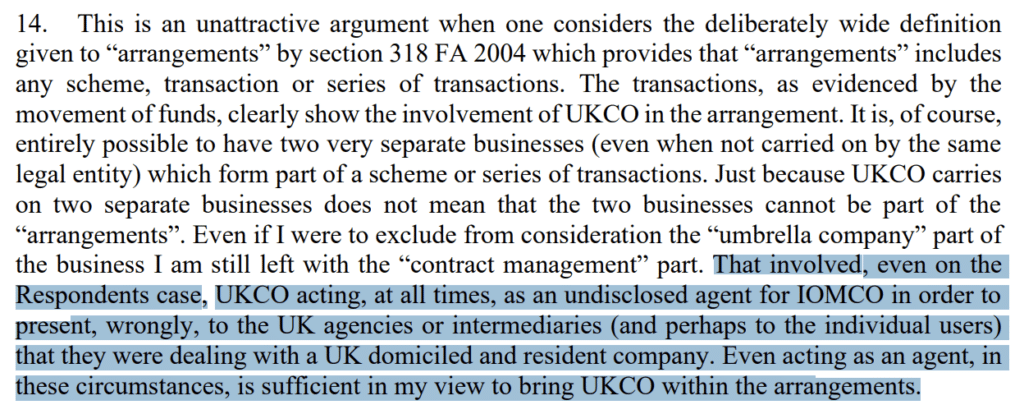

In trying to construct an argument for their scheme not being notifiable, the Smartpay companies (the “Respondents” in the tribunal hearing) admitted that the UK company acted as “undisclosed agent” of the Isle of Man company in order to trick employment agencies (and perhaps even the individual employees) into thinking that they were dealing with a UK company. Here’s the key paragraph of the tribunal judgment:

Undisclosed agency26 can be a perfectly proper arrangement.27 However in this case the employment agencies were seeking specific confirmation that the employer was a UK company. That was the whole purpose of the “compliance pack”.

The head of operations at Fuel Recruitment, told the FT his company only works with UK-registered companies and was only ever engaged with Smartpay Ltd in the UK. He added that he had “no knowledge of a business registered in the Isle of Man”.

In providing the pack from the wrong company, Smartpay was being deliberately deceptive, for the purpose of obtaining business that it otherwise wouldn’t receive.

The legal consequences

Did this mean Smartpay committed the criminal offence of fraud by false representation?

We asked Michael Gomulka, a criminal barrister at 25 Bedford Row who specialises in fraud. He says that fraud is “very simple… it’s making a dishonest misrepresentation for the purposes of making a gain for oneself or the risk of causing a loss to another”. And “prima facie, there appear to be good grounds for the authorities to investigate whether fraud was taking place” in Smartpay Limited’s dealings with its clients.

Here’s how the Crown Prosecution Service summarises the offence:

In this case it seems reasonably clear that a false representation was made (i.e. that the employer was a UK company), that those involved knew it was false, and that they made it to make a gain (i.e. earn fees from the arrangement, which they wouldn’t have earned if Fuel Recruitment knew about the Isle of Man company).

Were those individuals running Smartpay “dishonest”?

That means asking whether their conduct was dishonest by the standards of ordinary decent people (regardless of whether the individuals in question believed at the time they were being dishonest).28 The leading textbook of criminal law and practice, Archbold, says:

“In most cases the jury will need no further direction than the short two-limb test in Barton “(a) what was the defendant’s actual state of knowledge or belief as to the facts and (b) was his conduct dishonest by the standards of ordinary decent people?”

We expect most ordinary decent people would say the behaviour here was dishonest; but ultimately that is something a jury would have to decide.

Which individuals would have committed the offence? We don’t know who was operating the Smartpay business day-to-day, although we understand that Timothy Eve and Lisa Rowe run Barrowman’s tax business day-to-day. The director of the Isle of Man Smartpay Limited was Timothy Eve (the Deputy Chairman of Knox, Barrowman’s business). We don’t recognise the names of the individuals who were directors of the UK Smartpay Limited at the time.29 We also don’t know how involved Douglas Barrowman was personally in these arrangements.

We therefore believe there should be a criminal investigation into Smartpay. There is no statute of limitation on fraud.

Did the Smartpay companies avoid corporation tax?

The fact that Smartpay UK was acting as the agent of Smartpay Isle of Man means that Smartpay Isle of Man may be subject to UK corporation tax on its profits. We do not know if HMRC has already investigated this matter; if not, we believe they should.

Ordinarily 2015 is too long ago for HMRC to open an investigation (technically a “discovery assessment”), but if the Isle of Man company never notified HMRC that it had come within the charge to corporation tax, and the correct analysis is that it did, then HMRC are able to go back 20 years.

The PPE Medpro hypothesis

Given that we know the Smartpay Limited “shadow” was used to trick its commercial counterparties, the obvious question is whether the other “shadow” companies were used for the same purpose.

And there is one obvious suspect: PPE Medpro Limited.

The Guardian reported (and Barrowman does not seem to contest) that PPE Medpro made a £65m profit from its sale of £202m of PPE to the Government:

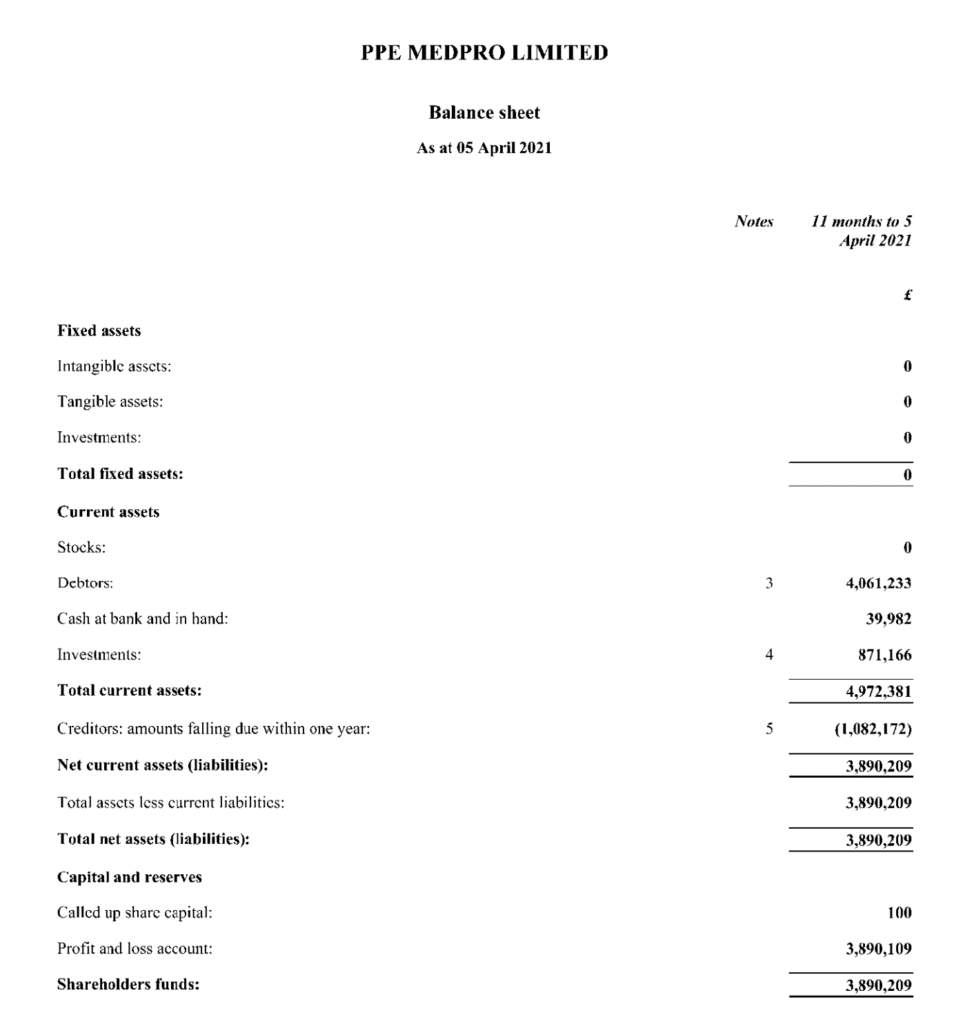

But whilst the Government certainly seems to have thought it paid the £202m to the UK PPE Medpro Limited,30 between 8 July 2020 and 28 August 2020,31 there is no sign of a £65m profit in the company’s accounts for the year ending 5 April 2021:

There is, in fact, only £4m of profit32, and no sign elsewhere in the accounts of the other £61m of profit.33

This is very strange, and there is a legitimate public interest in asking how a UK company can make £61m of profit without it appearing in the company’s accounts and (presumably) without the company paying tax on that profit.

We can probably discard three possibilities:

- The UK PPE Medpro received the £202m but paid most or all of it away in payments to other parties, leaving it with only a small accounting profit. In a normal case of buying products from a wholesaler and on-selling them, this would be uncontroversial. However in this case it would be highly aggressive from a UK tax perspective – I would expect HMRC to assert that paying out most/all of the £65m profit was not arm’s length, and therefore tax the UK PPE Medpro on some of that profit. There’s no sign that this has happened.34

- The UK PPE Medpro was acting as a disclosed agent for other parties. That would be consistent with the accounts, because it would be the other parties who received most, or even all, of the £202m and not UK PPE Medpro. It would in principle leave little UK tax in the UK PPE Medpro, save some small amount sufficient to remunerate it for its (minor) role. But the existence of an agency arrangement lets HMRC argue that the other parties have a UK taxable presence (a “permanent establishment”). This would therefore be a highly tax-inefficient structure. Furthermore, there is no sign of any agency in PPE Medpro’s contract with the Government, and it is not mentioned in the Governments’ civil claim (if the Government was aware of an agency relationship then it would usually want to add the principals as defendants, so it could seek recovery from them).

- Some very sophisticated and/or unusual accounting treatment. The FY21 accounts were prepared using the free Companies House filing service. The last two sets of accounts were prepared using Taxfiler – the cheapest alternative to the free Companies House software. We’ve spoken to accounting firms who believe this means the accounts were prepared in-house, without the involvement of a proper firm of accountants. It therefore seems unlikely anything very complicated is going on with the accounts

That leaves two other possibilities, which are more aggressive variants of the first two above.

- The UK PPE Medpro again pays most of the £202m away to other parties, leaving it with only a small profit, but argues that the payments are all tax-deductible and so it pays little or no corporation tax. This would be a bold claim, given the size of the profit, and an HMRC enquiry/challenge would be almost inevitable. This would, therefore, not be a structure most advisers would recommend. We would not necessarily know about any HMRC enquiry (such matters are confidential). Whilst there would often be a reference included in subsequent company accounts, the absence of such a reference does not mean there is no challenge.

- The UK PPE Medpro was acting as an agent for other parties, but an undisclosed agent. Smartpay’s trick was that Fuel Recruitment thought it was contracting with the UK Smartpay Limited, but was actually contracting with the Isle of Man Smartpay Limited. Could PPE Medpro have played the same game? The UK Government perhaps thought it was contracting with the UK PPE Medpro, but was actually contracting with the Isle of Man PPE Medpro (and potentially also with other parties.35). This again seems a real possibility. But an undisclosed agency arrangement could create serious legal jeopardy for Barrowman – it creates the potential for both a fraud against the Government (who thought they were contracting with a UK company) and a fraud against HMRC (given that the very tax-relevant agency arrangement would have been hidden from them).

These two scenarios feel more likely than the first two possibilities – but fundamentally all we have is the mystery of the UK PPE Medpro’s accounts. There is no evidence which lets us choose between these two scenarios, and it is perfectly possible there was some other scenario which we are missing. Isle of Man companies aren’t required to publish accounts. Barrowman shows no inclination to reveal any details of his business affairs, and indeed will break the law to keep his affairs private. The question of what happened to the “missing” £61m therefore may remain unresolved.

We expect that the Government will, in the course of its civil litigation, seek disclosure of the “behind the scenes” legal documentation that could shed light on what happened to the £61m of profit. We also expect that HMRC has open enquiries against the UK PPE Medpro and can issue an information notice requiring disclosure of all relevant documentation.36 If it doesn’t, we would urge HMRC to make a discovery assessment in light of Barrowman’s admission that the company made a large profit which (it appears) has gone untaxed.

What about the other five companies?

We currently have no explanation for the shadow companies other than Smartpay Limited and (possibly) PPE Medpro Limited. We have no evidence they behaved improperly; we also have no legitimate explanation for why they were established.

Barrowman’s response

We asked both Barrowman and his lawyers for comment, specifically asking why Barrowman operated identically named companies in different jurisdictions. Barrowman’s lawyers, Grosvenor Law, told us that “Mr Barrowman has confirmed that he has no intention to engage with you”. Barrowman didn’t respond, even when we put to him the fraud accusation concerning Smartpay Limited, and mentioned the admission by Smartpay in the tax tribunal.

It is very unusual for someone to respond to an accusation of fraud with what amounts to “no comment”.

A spokesperson for the Knox Group did respond to the FT, saying:

“We do not operate shadow companies and consider that your description of these entities is deliberately misleading. The Smartpay business was at all times a significant commercial operation. Disputes with HMRC happen across all business sectors and the matter to which you refer has been determined through a court process. All taxes have been paid. Further, PPE Medpro did not mislead anybody and all appropriate taxes have been paid.”

Note the absence of any denial that their standard practice was for the Isle of Man Smartpay Limited to employ the contractors, and then the UK Smartpay Limited to falsely represent to recruitment agencies that it was the employer. Instead this seems to be a denial of a tax evasion allegation which has not been made.37 It would, of course, be hard for Barrowman to deny something which his own companies admitted in court.

There is, on the other hand, a denial that PPE Medpro misled anybody. The problem for Barrowman is that he and his wife admitted lying when they denied any connection to PPE Medpro, didn’t seem particularly bothered by it, their own lawyer apologised for relaying their lies, and that Barrowman has also been caught lying denying his connection to another company. So, whilst this is a clear and direct denial, it is not necessarily one that we can believe.

The claim that “disputes with HMRC happen across all business sectors” is highly misleading. Our team has worked with a wide range of companies, from SMEs to the world’s largest corporations. Disputes with HMRC are indeed commonplace; but the disputes Barrowman’s companies have are highly abnormal. We are unaware of any legitimate business which has unlawfully failed to disclose tax avoidance schemes to HMRC on at least three occasions38. We are also unaware of any legitimate business which has been described by HMRC as using “a series of tactics to try and frustrate efforts to work out the tax legally due, in a sustained campaign of non-compliance”.

Douglas Barrowman told the FT:

“This deliberate witch-hunt is being pursued against me by individuals with hidden agendas, who hide behind their keyboards and invent theories of foul play at every situation — regardless of whether it bears any resemblance to the truth.”

Again, Barrowman’s problem is that previous “theories of foul play” turned out to be correct, as admitted by Barrowman himself, and that Barrowman has admitted not telling the truth. Given his failure to address the serious accusations which have been made, we expect people will form their own judgment as to who is “hiding”.

Thanks to V for helping review documentation, C, T and I for their helpful discussion around corporate structures, and Michael Gomulka and L for their invaluable input on criminal law and the modern dishonesty test. Thanks again to D for insurance advice, and to S for his review of our draft. Thanks to R for their accounting expertise. And to Anna Gross at the FT for her work developing the story, and in particular for asking the critical questions that led to us discovering the evidence of fraud.

Thanks most of all to Jane (who we cannot name), for providing the critical documentary evidence.

Footnotes

The UK PPE Medpro’s deep links to Barrowman are well documented, and whilst he initially denied any connection, he has since admitted it. The Isle of Man company has the same directors; Voirrey Coole and Anthony Page ↩︎

There is no connection between Barrowman’s Smartpay business and Barclays’ Smartpay payment solution. ↩︎

The Isle of Man company was called Smartpay Consulting Limited but changed its name to Smartpay Limited on 27 April 2015. The registered offices of both the UK and Isle of Man companies are associated with Knox/Barrowman. Email headers in emails sent by Smartpay refer to the sending IP address and internal networks used by Barrowman’s AML tax avoidance business. Smartpay legal documentation has metadata showing John Hardman as the author. Barrowman’s correspondence with the FT implicitly accepts that he controls Smartpay. ↩︎

Timothy Blackburn, a senior member of Barrowman’s team, is a director of the Malta company, and signed false documents on behalf of the company as part of the Vanquish scheme. The metadata in those documents shows John Hardman as the author – the former solicitor, struck off for dishonesty, who acts as Barrowman’s legal adviser. The Maltese company is owned owned by Soldado (PTC) Limited, which holds a property in Belgravia acquired by Barrowman and his wife ↩︎

The Isle of Man company is registered at Knox House. Lisa Rowe, who runs Barrowman’s tax businesses, is a director, and signed false documents on behalf of the company as part of the Vanquish scheme. We set out more of the evidence linking SP Management to Barrowman here. ↩︎

The Carnegie Knox website is currently down, so we are linking to an archived version on the Internet Archive. Note that some business networks block the Internet Archive; if this happens to you we suggest using your mobile or a home computer. ↩︎

We understand that the UK company has recently been sold to a third party; we do not know if the Isle of Man company has also been sold. We have no reason to believe that the new owner of Carnegie Knox (UK) was involved in any of the matters discussed in this report. ↩︎

We set out the evidence linking Vanquish to Barrowman here. ↩︎

It changed its name to “Lancaster Knox Consultancy Limited” in 2020 ↩︎

You can see that if you click “involvement” on the right hand side of this page ↩︎

The list below excludes a number of other UK companies with identical names to Barrowman tax haven entities, but where the UK company doesn’t have obvious signs of connection to Barrowman. These include AML Developments Limited, Precision Umbrella Limited, Deep Blue Contractors Limited, Modus Umbrella Limited, Amaze Umbrella Limited, Falcon Contracts Limited. The opencorporates database shows these UK companies as part of the Knox group – that may be a mistake for at least some of the companies (e.g. Falcon Contracts Limited appears entirely unrelated). ↩︎

We are also excluding Monthly Advance Loans Limited, as the UK company appears to serve UK customers and the Isle of Man company served Isle of Man customers (although it appears to have ceased that business and changed its name last year to MAL Technology Limited). Regulatory considerations often mean that consumer lending has to be carried out by a locally-incorporated company, although it is still unusual to use the same name in two different jurisdictions ↩︎

We have, after some thought, excluded one company which have Paul Ruocco and Knox links, but which we are not confident are part of Barrowman’s group: Umbrellaworx Limited, which runs a live contractor umbrella scheme, is the name of both a UK company and a Maltese company. ↩︎

i.e. stopping some third party setting up a UK company with the same name as your foreign company, and then leaving the UK company dormant ↩︎

With the exception we note above, Monthly Advance Loans Limited, where the Isle of Man company does appear to have undertaken Isle of Man business, and therefore it’s not included in our list of seven. ↩︎

We are aware of one multinational which had two similarly named companies (something like “Pineapple 58233 Ltd” and “Pineapple 582233 Limited”) and accidentally put the wrong company name on an important contract it had signed with a third party. Extricating itself from that mess was very expensive. ↩︎

There are surprisingly few multinationals which fully disclose their group structure. A rare example is Shell, which (commendably) lists all the 900+ companies in its group (with no duplicated names). A very different example is FTX, one of the world’s worst run and most corrupt businesses. Here’s its group structure – each entity has a different name. ↩︎

Not the contractor’s real name ↩︎

That’s the theory. Unfortunately the reality is that this arrangement creates lots of opportunities for bad actors to abuse tax and employment law, and downright commit fraud. A recent government consultation may improve things. ↩︎

Many people we speak to who are active in this area believe that some recruitment companies have connived in bad, and even criminal, behaviour by umbrella companies. Fuel Recruitment, by contrast, were extremely straight with the FT, and it is in our view clear that they had no involvement in Smartpay’s unethical and perhaps illegal behaviour ↩︎

It’s unclear why some emails came from smartpaylimited.co.uk and some from smartpaylimited.com. ↩︎

The company is shown as Smart Pay Limited; there seems to be some inconsistency here. Even the current website shows the spelling as “Smart Pay Limited” on the homepage, but “Smartpay Limited” in the privacy policy. As far as Companies House is concerned, Smart Pay Limited is the same as Smartpay Limited, which is the same as S M Artpay Limited. Spaces and punctuation don’t matter. ↩︎

The arrangement may have invalidated the insurance, in which case there may also have been a false representation that the employee was properly insured. However the impact of the undisclosed agency on the insurance is a difficult question, dependent on the precise terms of the insurance (which we have not been able to review). ↩︎

Metadata is the hidden information contained in computer document files. For example, if you open a PDF document in Adobe Acrobat, then click “File” and “Properties”, you will see the author of the document (or at least the person whose details were entered into the application that generated the original document) and the details of the application that generated the PDF. Metadata should be interpreted with caution. It can be easily faked. More importantly, metadata does not tell you who wrote a document. The default setting is that the name of the “author” is taken from the current logged-in user of the machine on which the PDF was created, but this default can be changed. Someone else could be using that person’s computer. In this case we have seen metadata identifying Hardman as the author across a large number of documents used by many members of Barrowman’s group. It is therefore a reasonable inference that Hardman, or someone working closely with him, is responsible for the documents. We have also had confirmation from independent sources that Hardman acts as legal counsel to Barrowman and the Knox Group. ↩︎

Under the “DOTAS” rules – there is extensive HMRC guidance on the rules here. ↩︎

We are not sure if the UK company was truly acting as an “undisclosed agent”; that would have required an appointment by the Isle of Man company. It would also have had VAT, corporation tax and possibly insurance law and employment law consequences. A proper assessment would require a review of the full facts and circumstances surrounding the relationship between the two Smartpay entities, including legal documentation. That will not change the potentially criminal consequences of a fraudulent misrepresentation, but could impact these other issues. ↩︎

For example someone purchasing goods or real estate may be acting for a particular end-purchaser, but think they obtain a better price by not disclosing the identity of the end-purchaser to the seller. That might annoy the seller, but it’s not fraud. Unless the seller asks “are you buying for yourself, or are you acting for another party”, and the buyer lies – then it is potentially fraud. So, where it matters, particularly in financial contracts entered into by regulated parties, businesses often require a representation that their counterparty is not acting as agent. ↩︎

The subjective element of the test for dishonesty (see Ghosh (1982)) was removed by Ivey [2017] for civil cases, and that decision was confirmed to apply to criminal cases in Barton [2020]. The fact that a defendant might plead he or she was acting in line with what others in the sector were doing, and therefore did not believe it to be dishonest is no longer relevant if the jury finds they knew what they were doing and it was objectively dishonest. ↩︎

Paul Ruocco, who has extensive Barrowman connections, became listed as the “person with significant control” of the company in 2017, and became a director on 1 November 2019. ↩︎

Curiously the company number on the original PPE purchase contract is redacted, but the address matches the registered office of the UK PPE Medpro at the time, and the Government’s particulars of claim specify the UK company. Hence it seems reasonably clear the contract was with the the UK company. ↩︎

See paragraph 36 of the Government’s particulars of claim ↩︎

The profit and loss account balance doesn’t necessarily tell us that – there could have been dividends. But the accounts show £913k owing to HMRC and, whilst some of it could be PAYE for the month, we expect most of it is corporation tax. That implies a profit of around £4m. ↩︎

It is also possible that some or even all of the £4m comes from another source, as the company made a similar amount of profit in the following two years (suggesting PPE Medpro had another source of income).33Note the £4m of “other debtors”. If these related to PPE supply, we would expect them to be ‘trade debtors’. This suggests that money has come in and been loaned to another party. ↩︎

There is a tax and social security balance in the accounts of £931k. This will likely be a mix of corporation tax and VAT (on the basis that there’s unlikely to be PAYE given there are no staff disclosed). Assuming that all is corporation tax, this would imply a taxable profit below £5m (based on a headline rate of 19%) if all the tax was paid post year end, as would normally be the case for a small company. ↩︎

Barrowman has mentioned a “consortium”, but the UK PPE Medpro is clearly not a consortium itself – perhaps it was fronting for the consortium via an undisclosed agency of some kind? ↩︎

Although Barrowman’s companies do not always comply with such notices. ↩︎

The statement also amounts to an admission than Smartpay is part of the Knox Group, which we believed was the case but can now be considered confirmed. ↩︎

Smartpay, AML and AML/Denmedical; we also understand there were additional cases which Barrowman companies conceded before they reached a tribunal. ↩︎

15 responses to “Barrowman – more evidence of fraud: his seven mysterious “shadow companies””

Were the payments for the PPE equipment, totalling £202 million, made directly to the UK bank of PPE Medpro?

If the payments were made from the UK Government, Department of Health and Care to PPE Medpro’s UK Bank account that’s a clear transaction to the UK version of PPE Medpro. If the payments were made from the UK Government, Department of Health and Care to an offshore PPE Medpro account then the UK Government has failed to apply due diligence regarding the payments corresponding to the UK(?) company that issued the invoice, or indeed, purposely overlooked this complication?

We don’t know! But if IoM PPE Medpro had a UK bank account then it’s very hard for anyone paying them to know it’s an IoM company.

*if* that’s what happened, and we’ve no evidence that it has, just signs of previous chicanery involving “shadow” companies.

https://manx.news/court-overturns-extensions-in-5m-case/

I always assumed that UK PPE Medpro was an undisclosed agent of IoM PPE Medpro. And that the BVI loan was profit participating ie that BVI is owned by Barrowman (or Barrowman trusts) so that he can say that he doesnt own PPE Medpro (albeit the BVI loan means that he is entitled to all/99.9% of the profits).

thanks, David. I agree undisclosed agency looks plausible. Wouldn’t a profit-participating loan mean a big denial of deductibility in UK PPE Medpro and hence a big tax bill?

Dan

Thanks

If anyone wants to take the the time to drill down to Companies House information on the numerous individuals who have been directors in the UK registered Smartpay Limited then:

What I thinks makes interesting reading is the fairly short periods of appointment, involvement in dissolved/liquidated companies and lack of subsequent company appointments of most of these individuals.

It makes you wonder why and how they got involved with Smartpay Limited.

From what I have read I think that, as well as Barrowman, others have made large profits out of selling PPE and some may well have avoided/evaded paying UK tax on all their profits.

In my view It would appear sensible for HMRC to obtain details of all the contracts the government entered into to purchase PPE in order to then decide whether to examine/investigate the accounts of the contracting persons.

As regards Barrowman and some of his associates words fail me.

Great article as always Dan. It seems ironic that you (effectively a public figure) are being accused of hiding behind a keyboard!

One small typographical point. Where you say: “there is no sign of a £65m profit in the company’s accounts for the year ending 5 April 2023” I think you mean “5 April 2021”.

thank you!

Dan – might be worth adding that HMRC should be able to get information on the IoM companies (particularly PPM Medpro) under the Exchange of Information provisions in the U.K./IoM DTA (Article 26).

I’m confused by “My Hoyler” of Pathfinder Tax Services Limited from the Tribunal’s decision, who was not interviewed but provided evidence on behalf of Smartpay. Pathfinder Tax Services Limited has a Mr Horler but not obviously a Mr Hoyler. It would be ironic if Smartpay’s witness also had confused names…

https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/08534468/officers

It’s a standard playbook, also used by those that deny conspiracy theories (which history later proves were sometimes right!). Property 118 are trying this too. The example from Yes Prime Minister is the one though that always jumps out to me, by the Master in this art, Sir Humprey Appleby.

In “Man Overboard”, Sir Humphrey decides to derail the Employment Secretary’s military relocation proposal by attacking the Employment Secretary’s character (by framing him as disloyal to the Prime Minister and plotting a leadership challenge) rather than attacking his proposal. He lampshades it by announcing that he’s “decided to play the man instead of the ball”.

I suggest that having a UK company and an offshore company with the same name is more common than you think. It’s a cunning ploy that I used to come across a fair bit when looking at bulk UK and non UK registrations in a former life

What did they do it for?

Nicely done Dan. In relation to the Barrowman statement:

“This deliberate witch-hunt is being pursued against me by individuals with hidden agendas, who hide behind their keyboards and invent theories of foul play at every situation — regardless of whether it bears any resemblance to the truth.”

Do you have any idea what the “hidden agendas” that he is referring to are? All the agendas that I can think of seem to be laying face up on the table.

Thanks

I think he believes there’s a massive conspiracy involving the Conservative Party, the Labour Party and the press. I’d ask him if it also involves shapeshifting lizards, but he doesn’t reply to my emails.