There has been a huge amount of controversy over the inheritance tax changes in last year’s Budget. They raised £500m, but hit some small farms and small businesses unfairly – whilst not stopping much existing inheritance tax avoidance. There’s a new proposal from CenTax which seems to do the impossible: protect small farms and businesses, counter tax avoidance more effectively, and double the yield to £1bn.

CenTax are proposing a “minimum share rule”. Where a farm/business forms at least 60% of an estate, there would be full relief from inheritance tax up to £5m per person (so £10m for a married couple). For £5m-10m per person there would be 50% relief. After £10m, no relief.

I’m convinced this proposal would be fairer for small farms and businesses, tougher on avoidance and raise more tax.

Inheritance tax – the background

If someone dies then their estate1 pays inheritance tax (IHT) at 40% on all their assets over the £325k “nil rate band” (NRB).2 A married couple automatically share their nil rate bands, so only marital assets over £650k are taxed.

Transfers to spouses are usually completely exempt from inheritance tax. So, for a married couple, in most cases there’s only inheritance tax when the second spouse dies.

The Cameron government introduced an unnecessarily complicated additional “residence nil rate band” (RNRB) where the main residence is passed to children. This is £175k per person, and again automatically shared between married couples. So for most married couples, only marital assets over £1m are taxed. The RNRB starts to be withdrawn (“tapers”) for assets over £2m (with planning, a married couple can keep the RNRB with joint assets of over £2m3).

Before the Budget

Before the Autumn 2024 Budget, private businesses and farms were often completely exempt from inheritance tax (IHT).

Agricultural property relief (APR) removed the IHT charge on the agricultural value of farmland, farm buildings and usually most of the farmhouse.

Business relief (BR) removed the IHT charge on businesses – including farm businesses and farm assets such as machinery and livestock.

In practice, qualifying APR/BR assets were entirely exempt with no cash cap. This protected small farms and small businesses. However it went further than that:

- The exemptions had no limit. What made sense for a policy perspective for a small farm or family business doesn’t really make sense for a £7bn business – but the exemption covered it just the same.

- The exemption doesn’t apply to shares in listed/quoted companies, for the very good reason that you can easily fund the tax by selling the shares in the market. But shares in alternative markets like AIM aren’t considered “quoted” for this purpose, even though you can easily fund the tax in precisely the same way. So there’s a large market in AIM portfolios designed solely to save inheritance tax. This has no public benefit – it reduces tax take, distorts investment, and artificially inflates AIM valuations (hence reducing yield).

The Budget 2024 changes

The Budget put a combined cap of £1m per person on agricultural property relief and business relief. Up to that cap, there was still a complete exemption from inheritance tax (except for AIM shares).

Above the cap, relief was cut to 50% – so the marginal IHT rate on qualifying farm/business assets beyond the cap became 20%, not 40%.

That sits on top of the standard IHT thresholds: the £325k nil-rate band (NRB), the £175k residence nil-rate band where a home passes to direct descendants, and the usual spouse exemption.

The Budget changes apply from April 2026 and raise raises £500m per year by 2029/30 (more in earlier years).

Why most farms and small businesses wouldn’t be taxed…

The upshot for farmers and owners of small businesses:

- For a single farmer who has no material assets other than his or her farm and farmhouse, and plans to leave everything to their children, the new APR/BR cap plus the nil rate band plus the residence nil rate band comes to a maximum of £2m.4

- For a married couple who plan to leave everything to each other and then their children, the new cap plus nil rate band plus residence nil rate band comes to a maximum of £4m with some basic planning.5

For farms/businesses larger than this, the answer in principle is to gift property above the £2-4m limit. Provided they live for seven years, the gift will be entirely outside inheritance tax and, if the owner/farmer is still relatively young (say no older than 70) it will be relatively inexpensive to insure against the risk they died early.

… and why some farms and small businesses would

In practice that £4m figure may not be achieved. Some farmers are unmarried; some married farmers’ spouses aren’t involved in the business.

And the “gifting plus insurance” strategy doesn’t work for everyone.

- An owner/farmer may be elderly, and not expected to live for seven years (so gifting won’t work and insurance is unavailable or expensive). This is why the Office for Budgetary Responsibility costings show the IHT changes yielding the most revenue in the first few years, from the “too old to gift” cohort. After that point, gifting/planning is expected to reduce revenues.6

- Many small farmers have no material income or assets other than their farm, and expect their “retirement” to be funded through farming income. So it won’t be always be easy for them to make a significant gift to their children (and a gift has to be real to count as a gift for IHT purposes).

All of this means that the consequence of the Budget changes are more nuanced than most media coverage (on both sides) suggests:

- Only a few hundred small farm estates will end up paying significant amounts of inheritance tax. The CenTax report has more data and details on this.7

- Other farms will spend time/money putting planning in place so they don’t pay significant amounts of tax.

- This will be a source of worry and stress for many people, even if their estates don’t end up paying tax.

Why should we care about someone with £5m of assets?

An obvious response to the above is: everyone else pays inheritance tax. Why should farms and small businesses be any different, particularly if they own assets worth millions of pounds?

It’s helpful to compare the position of someone inheriting £5m of cash/securities and someone inheriting a £5m farm or small business.

If I was lucky enough to inherit £5m of cash or securities, I’d receive £3m after inheritance tax.8 I could invest that in a fund tracking worldwide equities9 and expect to be able to maintain the value of the £3m (after inflation) whilst taking out around £120,000 each year. Or someone with a higher risk tolerance might even keep the £5m portfolio, and borrow £2m secured on the portfolio – I might expect the long term return on the portfolio (7%) to exceed the cost of the borrowing (5%).10

This doesn’t seem a particularly harsh outcome. After all, I’d have paid at least 40% tax (or more) if I earned £5m – it’s not clear why there should be less tax when I’m getting the money for nothing. And most people could live very comfortably for the rest of their lives on £120,000 of passive income.

Now let’s look at what happens if I inherit a £5m farm or small business, and ignore the house and other assets for now. If my parents put simple planning in place, £2m will be fully covered by APR/BR, and the rest benefit from 50% APR/BR. Meaning the tax bill is £600,000 – 20% of £3m.

I probably can’t sell £600,000 worth of the farm/business to pay this. It’s hard to sell part of a small business, and farms cease to be viable below a certain size.

Nor can I easily fund the tax by borrowing. HMRC lets me pay the inheritance tax over ten years and interest free – i.e. £60,000 per year. That means I need the business to generate a 1.2% return to cover the cost of the tax.

Many small businesses would be able to do this – but many small farms will not. The profit from farming often represents a very small percentage of the value of the land. I’ve spoken to farmers who own land worth £5m whose net income is around £50,000. That seems economically contradictory, even impossible, but it’s nevertheless the case.11

The result would be that the heirs would be forced to sell the farm to pay the tax. The farm as a unit would be unviable. That is undesirable – not just for the family directly affected, but for the local community.

The problems with the Budget changes

This illustrates an obvious problem with the Budget changes: in a small but significant number of cases, small farms bear a cost they cannot afford, and will end up being broken up.

There’s a second problem: the changes don’t remove the tax avoidance opportunities of BR/APR. I can acquire (for example) woodland purely to avoid inheritance tax, and it’s still completely effective for the first £1m, and worthwhile (50% relief, so an effective 20% inheritance tax rate) for the rest.

The question is how we fix this.

Our proposal: clawback

Last year we spoke extensively to farmers and farm tax advisers, and proposed a solution – “clawback“.

We suggested keeping full APR/BR for genuine farm succession but clawing it back if heirs sell the farm within a long, tapering period. That would make farmland useless as a bolt‑on IHT shelter: if your children cash out, the tax is reinstated.12

Since we were only seeking to protect small farms, we suggested there should be a £20m ceiling on the exemption.

This had two effects:

- Someone inheriting a small farm and continuing to farm it (or lease it to a tenant farmer) would continue to benefit from a complete inheritance tax exemption

- Someone inheriting farmland/woodland acquired for inheritance tax planning purposes would likely want or need to sell it (given the low yield); but they then wouldn’t benefit from the inheritance tax exemption.

The proposal therefore was tougher on tax avoidance than the Budget proposal, whilst also protecting small farms.

Clawback was widely supported by farmers and the National Farmers’ Union. However it has failed to achieve any traction with Government. I believe the main reason is that there is simply no data that lets HMRC or HM Treasury model the revenue impact of clawback. There may also have been a concern that it wasn’t possible to design and implement clawback by April 2026.

It therefore doesn’t look like there is any realistic possibility of clawback being implemented.

A better proposal: CenTax’s “minimum share rule”

CenTax have published a paper proposing a minimum share rule (MSR).

The idea is that, to get agricultural property relief or business relief , a minimum share of the estate must be made up of qualifying farm/business assets. If farming/business is what you do, you hold more than the minimum share, and get relief up to a generous allowance. If you’re a wealthy household that bought some farmland/woodland to save inheritance tax, you don’t.

CenTax present various possible scenarios, but the one I think is most workable is as follows:

- A minimum share set at 60%. All the small farmers I’ve spoken to would easily clear this hurdle – their farmland, business and farmhouse amount to around 90% of their overall assets. Most small businesses would too.13

- If the value of the farm/business is at or over the minimum share, APR/BR provide a complete exemption up to a £5m combined APR/BR allowance. This is per-person, so a married couple should benefit from a combined £10m allowance. The allowance should transfer between spouses, in the same way as the nil rate band and residence nil rate bands currently do. Above the £5m per-person allowance, there would be 50% APR/BR relief, i.e. a 20% effective inheritance tax rate.

- If the value of the farm/business is below the minimum share, APR/BR is not available, so the full 40% IHT rate applies.14

- There would then be a £10m (per person) upper limit to any APR/BR relief. After that, inheritance tax would apply at the usual 40% rate.

I believe this is a better solution than clawback.

It protects small farms just as effectively than clawback (but without the complexity of worrying that subsequent unplanned sales of land/assets could trigger a large IHT charge).

It counters artificial use of APR/BR for avoidance purposes more effectively than clawback, because it’s not reliant on a subsequent event the timing of which would be uncertain. And it does this much more effectively than the Government’s proposal, because tax planners no longer get a £1m exemption to play with.

It should be possible to implement by April 2026, although some of the detail (and anti-avoidance) would need careful thought.

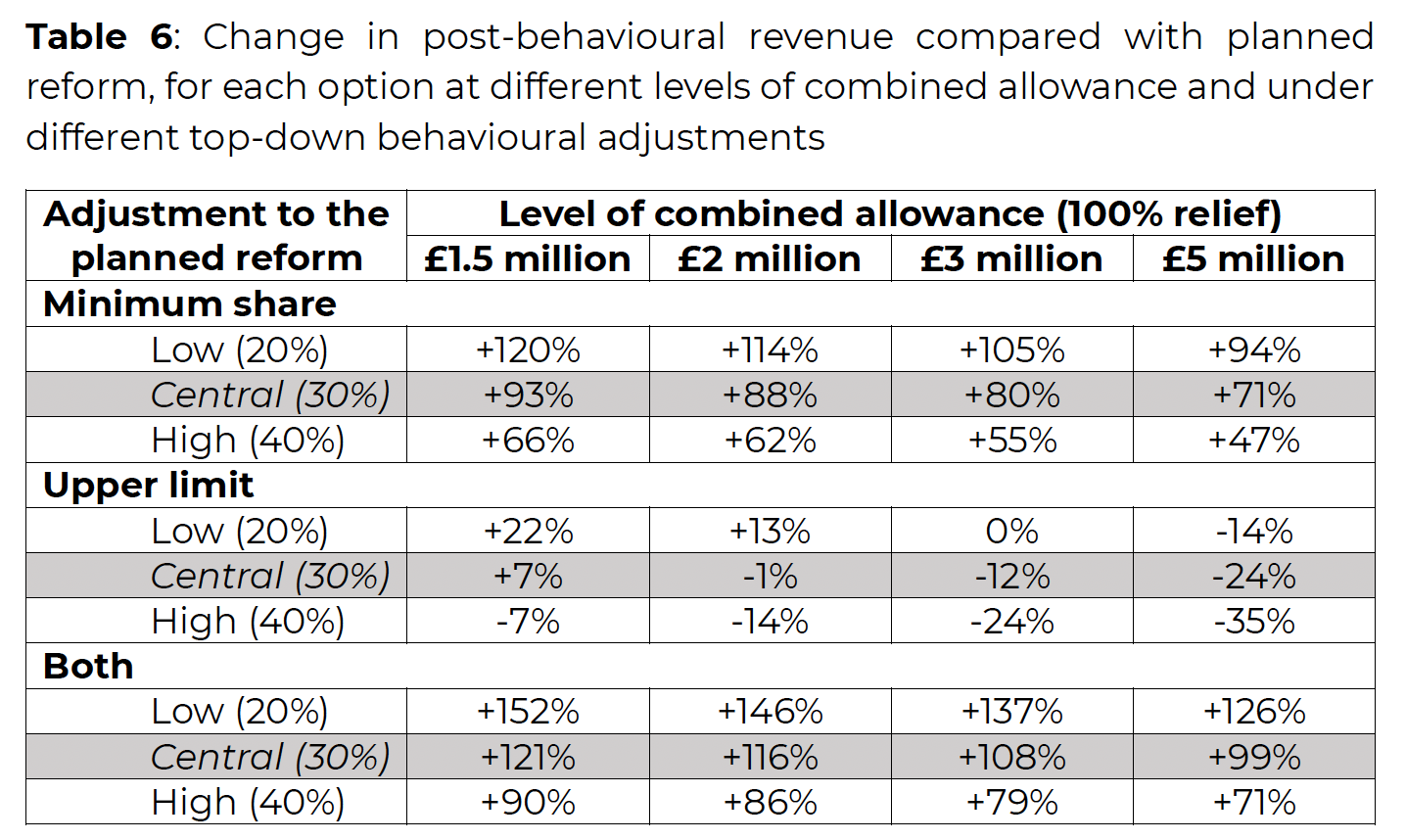

Most importantly from HM Treasury’s perspective, existing IHT data can be used to estimate the revenue impact. Here’s CenTax’s figures:

My favoured scenario is in the bottom right – the central estimate is that this doubles the revenue from the Government’s IHT reform. So instead of raising £500m by 2029/30, it raises £1bn.

I won’t try to reproduce CenTax’s full technical design here – their paper isn’t short – but the policy principle is a simple one: relief should reflect how far the estate is genuinely a farm business or small business. That’s hard to game, easy to administer off the existing data model, and it avoids pushing viable farms into “sell land to pay the tax” decisions that the Budget proposal inevitably creates.

I think it’s a very good idea – I hope Government and representatives of farmers and small businesses give it careful consideration.

Thanks to the farmers, advisers and policy folk who commented on a draft of this note. Any errors are mine.

Footnotes

The “estate” here has a different meaning from the way the word is often used, e.g. “landed estate”. The “estate” is the legal fiction that springs up when someone dies – the executors manage the estate, and inheritance tax is charged on (usually) the estate. ↩︎

The estate pays as a legal matter, but realistically the burden of inheritance tax falls on the heirs – they’d (obviously) receive more if there was less/no IHT. ↩︎

In principle the RNRB could be retained in full with joint assets up to £4m, but in practice changes in asset values between deaths make this very unlikely. ↩︎

This is because of the order in which reliefs apply. The first £1m is completely relieved by APR/BR. The remaining £1m benefits from 50% relief, leaving £500k. That £500k is covered by the NRB/RNRB. ↩︎

That works as follows. The first of the couple to die leaves £1m of farm/business assets to their children, completely relieved by APR/BR – so no IHT, and the rest to the surviving spouse. The second to die leaves £3m to their children. £1m of that is completely relieved by APR/BR. The remaining £2m has 50% relief, leaving £1m. That £1m is covered by both spouses’ combined NRB/RNRB. But the residence nil rate band tapers, so in practice the full £4m will not be available in all cases. ↩︎

CenTax concludes that, amongst farm estates worth less than £2.5 million, only 15 estates per year would face an increase larger than 5%. All of the 25 farm estates per year facing an increase larger than 15pp are valued at over £7.5 million. See Figure 12 on page 50. ↩︎

Let’s assume a simple 40% flat rate here; perhaps I inherit a house as well, some/all of which is covered by the nil rate band and residence nil rate band. ↩︎

That is of course not an investment recommendation, but in a “I take no liability” sense I strongly recommend investing in an index-tracker ETF. ↩︎

Although there is a tax gotcha here – the return on the portfolio is taxable but the cost of the borrowing is usually not deductible. So a 7% return after tax will be very similar to the 5% cost of the borrowing ↩︎

Why? Some mixture of: farmland prices reflect development potential, even if the chances of planning permission are very low; farmland prices reflect demand from people owning large houses who’d like to acquire the neighbouring fields; and – not least – they also reflect demand from people looking to avoid inheritance tax. ↩︎

Clawback isn’t a foreign concept: there are examples elsewhere in UK tax (e.g. SDLT relief withdrawals, CGT holdover relief, and VAT partial exemption adjustments) and in Ireland’s agricultural relief rules. ↩︎

The fact their house doesn’t qualify for relief means that their business assets typically form a smaller percentage of their overall assets. ↩︎

This would be a “cliff edge”, with 0% relief switching straight to 100% relief at the 60% point. Cliff edges are usually undesirable features of a tax system, but the reasons explained in the CenTax report, it’s probably the best way for the minimum share rule to apply. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Jerry Giles Cancel reply