This Government was elected on a platform of kickstarting economic growth. It has a large majority, and four or five years until the next election. It’s a rare chance for real pro-growth tax reform. That’s all the more necessary if we are going to see tax rises.

We’ll be presenting a series of tax reform proposals over the coming weeks. This is the first: how to reform corporation tax.

Most of the tax changes we hear about, in Budget speeches or newspaper columns, are driven by necessity or politics. But there’s more to tax policy than tax hikes or tax cuts, which garner headlines out of all proportion to their actual financial significance in the context of a £2.5 trillion economy. Much more important is tax reform – revenue-neutral changes that would drive economic growth.

Tax reform can do that by lowering the marginal tax rate on work (for example, cutting employee national insurance) or investment (for example, more effective investment reliefs).

But tax reform can also boost growth by reducing economic anti-growth distortions in the current tax system. There are all too many of those – for example, the way that stamp duty deters people from moving house in search of better opportunities elsewhere.

Between now and the Budget we’ll be publishing a series of articles on tax reforms we believe are badly needed. This is the first: corporation tax. You can see the complete set here

All of our proposals could be revenue-neutral, or raise or cut tax, depending on how they were implemented. But revenues aren’t the point: the idea is to make the tax system drive growth (or, at least, not hold it back).

These pieces are very much summaries rather than full proposals – each proposal links to more detailed analysis elsewhere.

The most complete guide to the wider issues around UK tax reform remains the Mirrlees Review – written in 2010, but still highly relevant today. It’s available for free here.

The problem with UK corporation tax

All taxes have two components: the rate, and the thing the rate is applied to – the base.

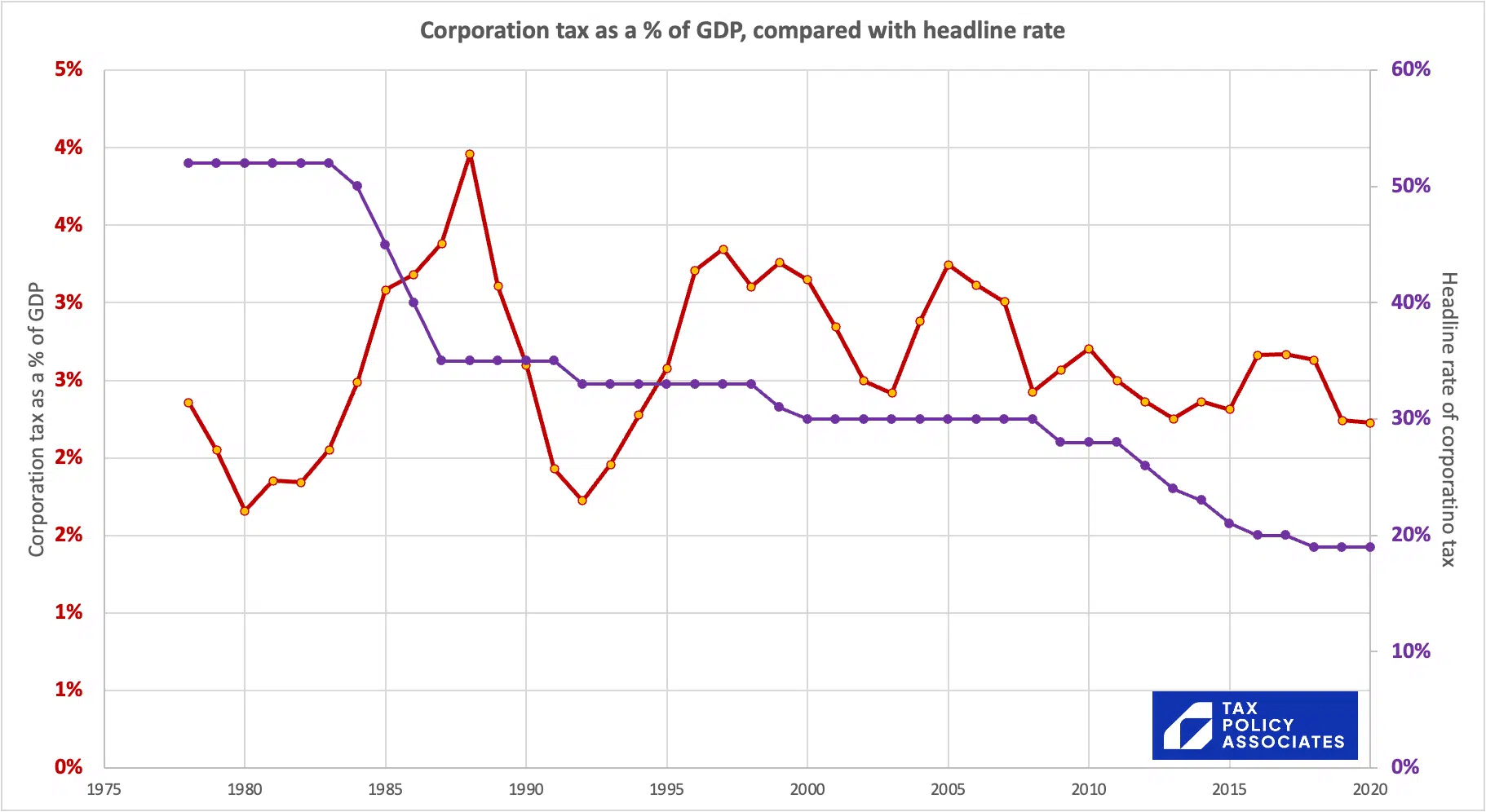

It’s always obvious when the rate changes, but changes to the base can be much less obvious. So, for example, the rate of UK corporation tax fell precipitously from 1980 to 2017 – and lots of people noticed that. However, over the same period – and unnoticed by most non-specialists – the base expanded dramatically. The interaction between these two effects meant that the actual corporate tax paid (as a percent of GDP) was largely unchanged over this period:1This is not a function of cherry-picking particular measures; however you cut it, the rate has dropped but revenues have not.

So the base is important.

But the UK’s corporate tax base is uncompetitive.

The UK’s corporate tax base is a mess, largely thanks to a mixture of historical accident and modern over-complication. If we reform the base, we could collect the same amount of tax, but reduce complication, create better incentives and make the UK more competitive – all of which would enhance growth.

My personal experience is that the complexity, uncertainty and constant change of the UK tax base deters foreign investment. However we can obtain a more dispassionate take on how the UK looks from outside thanks to the corporate tax competitiveness work carried out by the Tax Foundation, a US tax think tank.

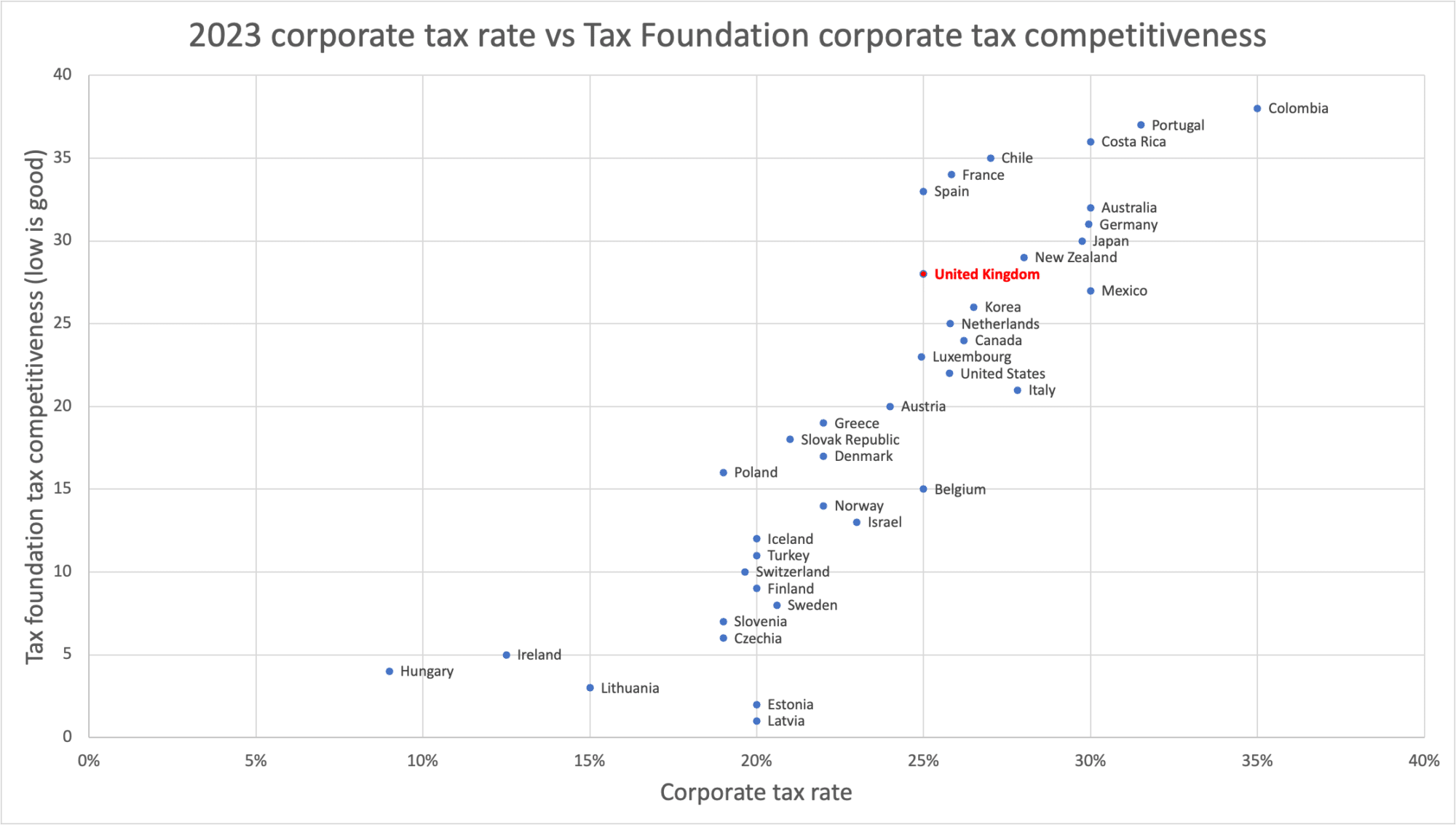

The Tax Foundation ranks every OECD country’s tax competitiveness, looking separately at different taxes. Each country’s ranking (1 is the best) is of course significantly driven by tax rates – but not only by tax rates.

Something interesting happens if we plot corporate tax rates against the Tax Foundation’s corporate tax ranking for each country. We see that the UK is much less competitive than other countries with similar rates of corporate tax. Indeed less competitive than Korea, Italy, Austria and Belgium, all traditionally thought of as high tax jurisdictions:2Data from the OECD tax revenue database.

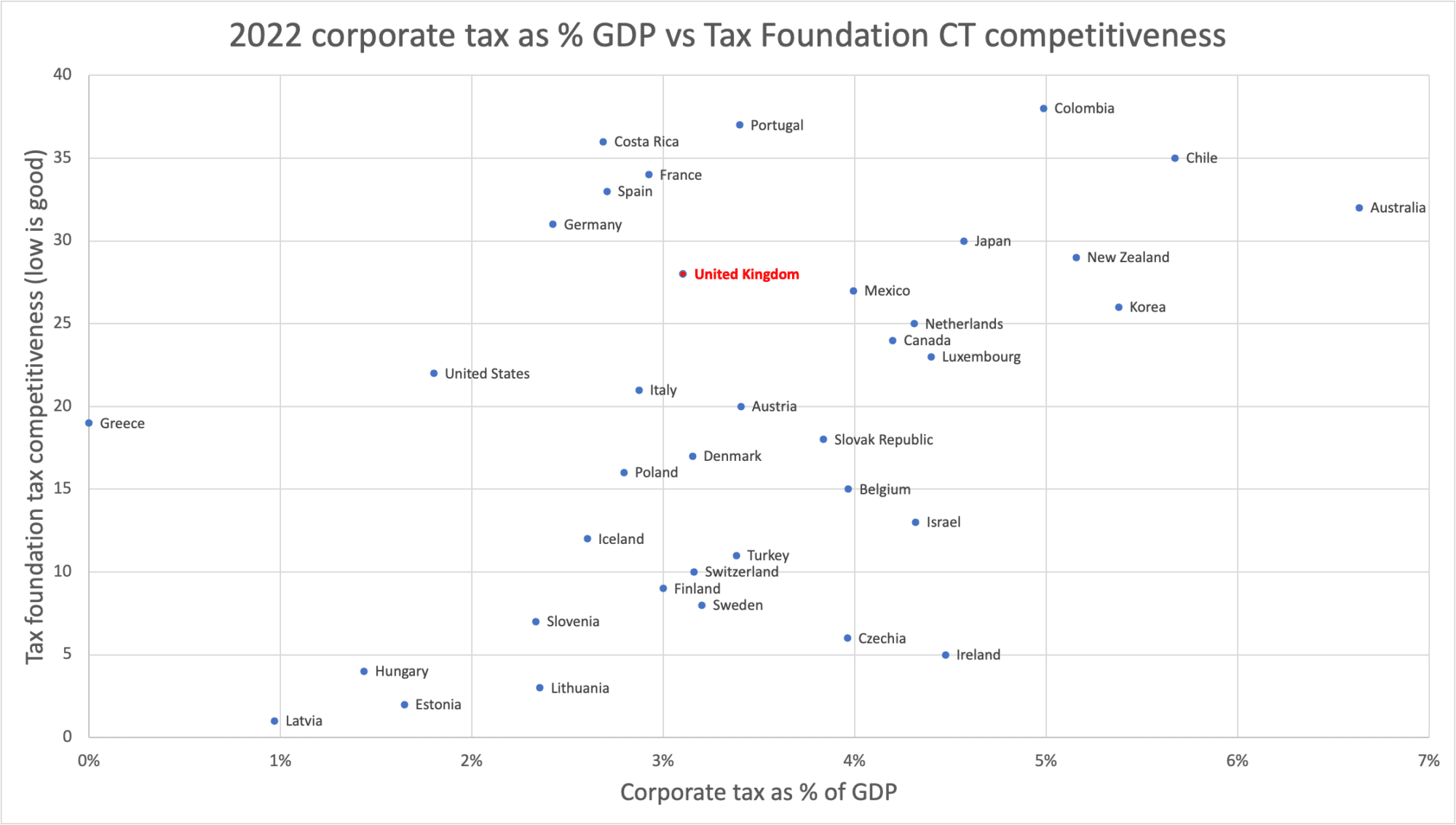

It’s not just the rate – we see the same effect if we plot corporate tax revenues as a % of GDP against the Tax Foundation’s corporate tax ranking. Many countries raise as much or more revenue than the UK, but have more competitive systems.3Data again from the OECD tax revenue database. Note that Greece is excluded because there’s no 2022 data as yet. Norway is excluded because its large oil and gas revenues make it an outlier that turns the chart unreadable.

So, to put it crudely, corporation tax reform should aim to move the UK vertically downwards in these charts. We can’t be Singapore or Hong Kong4It’s often suggested our tax system could be as simple as Hong Kong’s, which runs to a few hundred pages. But it’s clearly unrealistic to expect the UK (where government spending amounts to 45% of GDP) to have a tax system that looks anything like Hong Kong or Singapore (15% of GDP). City states with a very high proportion of highly paid financial sector workers are not remotely comparable to large diverse economies like the UK., but we absolutely could be Finland or Sweden.5Finland and Sweden are often viewed as high tax jurisdictions. From a personal tax perspective that is accurate. From a corporate tax perspective, the overall burden is similar to the UK; but the corporate tax systems are significantly simpler.

We could collect the same amount of tax, but with a better and more competitive6“Tax competition” is a bad word in some quarters. But, whatever you think about tax competition over rates, tax competition over complexity is a good thing. tax system.

(Or raise corporation tax, or lower corporation tax, as per your preference – nothing in this article is about the overall revenue raised).

The solution: radical simplification

Much of the reason for the UK’s poor performance in the Tax Foundation study is complexity.

An obvious measure of complexity is the sheer length of UK tax legislation. But to get a real sense of what it means in practice, one has to look at the actual steps a business has to go through to work out what its tax liability will be.

I went through an example last year. I looked at a typical and fairly straightforward arrangement: a US parent company financing its UK subsidiary, and went through the main rules the subsidiary would have to go through to establish if its interest payments were tax deductible. There were nine, often overlapping, and involving thousands of pages of legislation and guidance.

The worst of the nine was the UK “hybrid mismatch rules”, which aim to stop companies achieving a tax advantage by structuring an arrangement so it’s treated differently in two different countries. That principle is easy to state. The detail, on the other hand, is out of control – the guidance alone runs to 484 pages:

All of this complexity carries a cost.

Most obviously: companies spend time and money on tax accountants and tax lawyers. Without that, they wouldn’t be able to carry on in business. It’s facile to say we’d better off if the accountants and lawyers didn’t exist – we’d be worse off. But we would absolutely be better off if the need for tax lawyers and accountants was significantly reduced.

There’s also a cost in lost investment. Tax complexity creates tax uncertainty (and many of the nine rules I went through in the article linked above are deeply uncertain in their application). There is good evidence that tax uncertainty hinders investment.

I believe the complexity is mostly unnecessary. It has two main causes.

- First, the complexity is a fossilised remnant of a 70-year arms race between HMRC and tax avoiders. But the war is over. The attitude of the courts, and modern anti-avoidance rules, means that classic tax avoidance is dead. It’s time to recognise this, and repeal the hundreds of pages of rules that are no longer needed. Whilst at the same time making clear that HMRC will pursue anyone trying to take advantage of “loopholes” created by the repeals.

- Second, the historic common law approach to legislative drafting has reached its limit in modern internationally-coordinated tax rules. The result has been legislation and guidance of exquisite detail and painful length, which in practice fails to achieve the certainty that the common law approach always prized. We need to move towards principle-based drafting of complex rules.

The Office of Tax Simplification produced dozens of reports, running to tens thousands of pages, which could have achieved really significant simplification. But it never received political support, and very few of its proposals were enacted. That was a bad mistake. The abolition of the OTS was a recognition of a political failure by successive Ministers, not a failure by the OTS.

In the medium term, we need a kind of new OTS – but one that has heavyweight political support, and with a junior Minister attached, so that it is a body with real political weight.

In the immediate term, Rachel Reeves should lock some current and retired policy people in a room, and not open the door7Figuratively speaking. I am in not generally in favour of unlawfully detaining tax advisers. until they’ve identified dozens of provisions that can be repealed. I don’t think this is a difficult task.

A more ambitious solution: real full expensing

There are lots of problems with the UK tax base. But perhaps the biggest one is the oldest: companies can claim a tax deduction for their ordinary expenses (“revenue”) but not for investments (“capital”). This distinction doesn’t follow economic or accounting concepts; it’s purely a tax invention.8And a distinction that’s often very unclear, being entirely a creation of common law and not legislation. Advisers spend significant time advising whether a particular transaction is capital or income, and often end up having to advise on both bases, just in case.

It’s clearly suboptimal that the tax system incentivises current expenditure over investment. So the rules create a special case where companies can claim relief (“capital allowances”) for a certain type of investment – “plant and machinery”.

Capital allowances used to be claimed over time; now they’re usually claimed up-front, in “full expensing“.9There is a good guide to the rules from PwC here. But again that’s only for “plant and machinery”.

What’s plant and machinery? Inevitably, that’s not actually defined, although there are many rules excluding particular things (like buildings). There used to be an “industrial buildings allowance” which was very valuable to industry, but Gordon Brown abolished that in 2008 to fund a 2% cut in the rate. A more limited “structures and buildings allowance” was introduced in 2018.

This complexity is a problem. It creates uncertainty, which makes it hard for companies to plan, and therefore reduces the incentivising effect of the reliefs. It also creates a curious incentive towards investing in the particular types of asset which qualify – and there’s no good reason for this. Investing in buildings, intellectual property and other intangible assets should be treated in the same way.

The answer is simple: give up-front tax relief for all business expenditure.10i.e. expenditure satisfying the “wholly and exclusively” test. End the capital/income distinction.11The change would probably have to be prospective only in relation to losses. Many companies have huge amounts of historic capital losses which can’t be used against current (revenue) profits. There is no principled reason for this, and it should be changed going forwards. But enabling utilisation of historic losses would be very expensive; my belief (based on personal experience across the large business and financial institution sector) is that it would cost several billion pounds. Real full expensing.

If that’s the only reform that was made, it would be very expensive. It would also exacerbate the current distortion in favour of debt finance – you could claim tax relief twice for the same asset (once for the purchase of the asset, once for the financing cost).

Real full expensing therefore has to come with the quid pro quo of ending the bias towards debt, by making interest non-deductible12Excluding financial traders, such as banks, where interest income and expense is a fundamental part of the business. Taxing interest income but not giving a deduction for interest expense would end banks’ businesses overnight. Permitting a deduction for interest expense, but only against interest income, would result in distortive behaviour and avoidance. The Mirrlees Review discussed this problem in detail; I would duck it entirely by simply exempting financial traders.. There would need to be transitional measures or a de minimis (as for the existing corporate interest restriction) to prevent disruption to small business.

The aim should be to not change the overall level of tax on corporates, but to shift incentives decisively in favour of investment and away from financial engineering.

This is an area where plenty has been written – there’s an excellent piece from the IFS here.

Photo © The Labour Party, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

- 1This is not a function of cherry-picking particular measures; however you cut it, the rate has dropped but revenues have not.

- 2Data from the OECD tax revenue database.

- 3Data again from the OECD tax revenue database. Note that Greece is excluded because there’s no 2022 data as yet. Norway is excluded because its large oil and gas revenues make it an outlier that turns the chart unreadable.

- 4It’s often suggested our tax system could be as simple as Hong Kong’s, which runs to a few hundred pages. But it’s clearly unrealistic to expect the UK (where government spending amounts to 45% of GDP) to have a tax system that looks anything like Hong Kong or Singapore (15% of GDP). City states with a very high proportion of highly paid financial sector workers are not remotely comparable to large diverse economies like the UK.

- 5Finland and Sweden are often viewed as high tax jurisdictions. From a personal tax perspective that is accurate. From a corporate tax perspective, the overall burden is similar to the UK; but the corporate tax systems are significantly simpler.

- 6

- 7Figuratively speaking. I am in not generally in favour of unlawfully detaining tax advisers.

- 8And a distinction that’s often very unclear, being entirely a creation of common law and not legislation. Advisers spend significant time advising whether a particular transaction is capital or income, and often end up having to advise on both bases, just in case.

- 9There is a good guide to the rules from PwC here.

- 10i.e. expenditure satisfying the “wholly and exclusively” test.

- 11The change would probably have to be prospective only in relation to losses. Many companies have huge amounts of historic capital losses which can’t be used against current (revenue) profits. There is no principled reason for this, and it should be changed going forwards. But enabling utilisation of historic losses would be very expensive; my belief (based on personal experience across the large business and financial institution sector) is that it would cost several billion pounds.

- 12Excluding financial traders, such as banks, where interest income and expense is a fundamental part of the business. Taxing interest income but not giving a deduction for interest expense would end banks’ businesses overnight. Permitting a deduction for interest expense, but only against interest income, would result in distortive behaviour and avoidance. The Mirrlees Review discussed this problem in detail; I would duck it entirely by simply exempting financial traders.

15 responses to “How to reform corporation tax”

Just one further build on this: your excellent later piece on stamp duty/SDRT abolition points out the impact on cost of capital.

It’s therefore rather incongruous to be proposing abolition of interest deductibility, the detrimental impact of which on companies’ weighted average cost of capital would be (in most cases) an order of magnitude more significant than anything we do with stamp taxes.

You can debate how much debt is preferred to equity *because of* its tax deductibility, but clearly tax isn’t the only factor: debt is far more flexible and easier to source than equity. So increasing the cost of debt wouldn’t simply mean more equity in its place. Hence the cost of capital of most companies would increase significantly – which in turn drives lower investment.

Finally, interest deductibility is a *permanent* difference whereas full expensing is a *temporary* or timing difference only, so it’s really not comparing like with like. Most quoted businesses (and their investors) are primarily concerned about their earnings (an accounting measure) rather than net cashflows. Such a change would result in a permanent and ongoing reduction in net earnings and therefore an immediate crash in equity valuations – with all the associated knock-on impacts for pension funds and other investors. This might be regarded as “Trussonomics” on speed.

I only interact with these rules remotely and perhaps it’s more relevant to a discussion of NICS than CT but both the apprenticeship levy and Construction Industry Scheme have always seemed to me to be burdensome beyond their benefit.

I am all for more training and apprenticeships but let’s be upfront with how we fund them and simplify the tax returns by rolling these schemes into an amended rate or base for CT.

Further to your suggestion of unlawfully detaining tax advisors, it didn’t do Mick Jagger and Keith Richards any harm.

https://theweek.com/speedreads/446600/keith-richards-wrote-first-song-imprisoned-kitchen-mick-jagger

Totally agree with the move to principles based enforcement. This introduces self-enforcement as a key factor – much cheaper than HMRC pursuit of each and every chancer. It might be said to make matters less certain, but a combination of straightforward guidance in response to specific questions, plus caselaw, will rapidly provide certainty for business.

Are SBAs really more limited than IBAs? Ok, the latter were 4% compared to 3% for SBAs, but at least now you don’t have to rely on fitting within the “subjecting goods to a process” definition of industrial activity.

The rules for SBAs also seem less complicated, certainly for second hand buildings.

Under the charts from the Tax Foundation you mention “We can’t be Singapore or Hong Kong, but we absolutely could be Finland or Sweden.” It’s a shame neither Singapore nor Hong Kong are included in those charts so their relative positions could be compared to the UK, Finland and Sweden. It’s hard to know what we’re comparing to when the data aren’t displayed.

I was astonished at the claim accounting and economics didn’t distinguish between capital and revenue; happy to leave that oddity to others. Full expensing – including land and buildings which in the short or long term might even increase in value? I suppose you could try allowing a deduction for accounts-based depreciation but I suspect it wouldn’t take long before tax-defined rules were re-adopted.

The simplification of disallowing deductions for finance costs would achieve a substantial proportion of reform (and could offset a rate reduction if the full expensing option was seen to be too tricky for transitional rules) in TaxWatch’s view. We’ve advocated for such a reform in our submitted BudRep.

I think it’s worth stepping back and segmenting different forms of “investment”. In theory, building up a business and creating jobs that add value = good investment. Buying land & buildings, taking advantage of subsidies, hosting a pass-through trade.. these sorts of investment may or may not be good (their best feature might be their ability to bear tax, but they’re less likely to catalyse long term growth, and not as much of the deducted cost goes back into the economy).

So.. full expensing, except for land & buildings that have a future value.

Cap interest deductions, don’t eliminate them entirely (some leverage could be OK).

The obvious basic rate to go for is 20%. Don’t have marginal rates for companies as they get smaller.. give them other benefits designed to catalyse growth.

Most controversially, disallow all staff costs, pension contributions etc. That means IR35, all forms of NI and nearly all the crazy rules can just go. And the base that the 20% is levied on is MUCH bigger. To compensate, allow employers a targeted rebate for each job, more and an upfront element for newly created ones. PAYE and general taxation of employees and all individuals can then be made much simpler.. more anon on that.

Wouldn’t the effect of that be a sharp increase in the effective rate on manufacturing businesses (lots of plant and machinery already getting the expense deduction but hit by the non-deductibility of interest) and a sharp decrease for Property businesesses (little plant and machinery)?

I suspect one factor that might weigh against the neutrality would be the pressure to reduce tax on the recipients, both corporate and personal, of non deductible interest payments given the rates applied to non deducted dividends

If this is a summary of an item to come under the banner of “cutting red tape”, then it clearly makes sense to me. Anything that moves this government closer to the details underneath the glib simplification of populist headlines such as “cutting red-tape” will help us all.

Another superb series of suggestionss which, to someone who doesn’t understand the potential wrinkles,seems like good old common sense. More pertinently, is anyone listening – if not, why not, if they are, what are the blocking forces that means nothing changes? These should be non-partisan issues of competency and addressed accordingly but you are powerlesss if no one is listening.

It was all going so well until you went down the rabbit hole of full expensing. Where to start? Well for one thing, where do you get that there is no distinction between capital and revenue for *accounting* purposes? The fact that there is such a distinction (albeit not defined the same way as in the tax rules) is precisely one of the reasons why “full expensing” is useless for so many businesses, particularly those that are quoted and reliant on the (accruals-based) measure of EPS rather than particularly interested in cash/timing differences.

Full expensing is a red herring. The better way to simplify is to push further to ensure that tax follows accounting, so the tax result is predictable and the tax base closely follows the accounting base.

Appreciate that SMEs may have a different perspective – they are often more focused on cash than larger businesses (albeit that they statistically pay a small proportion of all corporation tax). Perhaps allow an opt-in regime for businesses below a certain size to be taxed on a net cashflow basis, perhaps even align the returns/collections to the VAT regime … but leave accounts-based taxation for larger businesses (and abolish the ‘full expensing’ white elephant!)

Agree with Dominic here. Full expensing coupled with abolition of interest expense deduction is nice in theory, but in practice it is too radical and would make UK real outlier. I can’t think of a single major economy that doesn’t allow corporate tax deduction for interest costs. Albeit that, post-BEPS, almost all have restrictions broadly equivalent to the CIR to limit deductions on shareholder debt..