We’ve been investigating a Belize company called GCWealth. It says its offshore trusts can eliminate tax on your assets, and prevent your spouse or creditors ever accessing the assets. And GCWealth claims that billions of pounds have been put into their schemes in the last fifteen years.

Our experts believe GCWealth’s claimed tax, divorce and insolvency benefits don’t actually exist. The schemes only work if the authorities don’t find out about them. That suggests this may be fraud, not avoidance.

The GCWealth schemes, like others before them, shows that the current approach to dealing with tax avoidance isn’t working.

Promoters remain free to push highly aggressive schemes that border on fraud. They do so from offshore companies that – they think – make them untouchable. And we believe that this kind of avoidance/evasion is part of the reason why the small business “tax gap” is so large. It’s time to make promoters of such schemes pay, with harsh penalties and criminal sanctions.

This report outlines the GCWealth schemes, explains why they don’t work under current law, and proposes specific changes to criminalise promoters like GCWealth.

The two schemes

This is GCWealth’s document promoting its “business asset trust” (PDF version here):

The scheme works like this:

- GCWealth’s client declares a trust over property (or indeed any asset), so that it remains in the taxpayer’s name, but beneficial ownership passes to a Belize trust.

- The taxpayer sets up a new UK company which becomes the beneficiary1The document actually says that “the beneficial title sits” with the company. That can’t be right, because it implies the arrangement is a bare trust, which would have no tax effect. Probably the author doesn’t understand the difference between a beneficiary and beneficial title. of the trust2The document expressly says the company is the beneficiary of the trust. But it also says, in the previous sentence: “The trust structure is set up so that the power in the trust to hold the assets are held by the client in a UK new company specifically set up as part of the structure, of which the client is the sole shareholder and director” which is incoherent, but perhaps suggests the company manages the trust? (i.e. it’s a trust inside a trust).

- Then, through steps that are not set out in these documents, the asset supposedly becomes free from income tax, capital gains tax and inheritance tax.3These steps sometimes include an intermediate non-UK company which acquires the asset and makes the contribution to the trust. This appears to be an attempt to fool UK settlement rules – it won’t work.

- GCWealth also claim that the trust means that your “assets protected from 50/50 split upon divorce”. In other words, if you divorce, and a court split the marital assets, you’d keep all the assets in the trust.

- And GCWealth say the “assets [are] immediately sheltered from bankruptcy, insolvency proceedings”. So if you owe your creditors money, but have put assets in trust, your creditors wouldn’t have access to them.

These are bold claims.

Here is the document promoting a second scheme, the “creditor protection trust” (PDF version here):

This second scheme works like this:

- The client has a pre-existing small business run through a company.

- Normally the company would pay corporation tax on its profits, and pay dividends to the client – with the client paying income tax on the dividends.

- Under this scheme, all the profit made by the client’s company is contributed to the trust.

- GCWealth say the company’s payments to the trust are deductible for corporation tax purposes. So the company pays zero corporation tax.

- The money, now in the trust, is then lent by the trust to the client under successive ten year interest-free loans.

- And GCWealth say that the client receives the loans tax-free.

- GCWealth say the structure “spans over a hundred years in its use”. We don’t know what that means.

Again these are ambitious claims.

The PDF metadata4Metadata is the data created when by software that creates or edits documents, but which is not visible onscreen when you view the document. The metadata in a PDF file can, for example, be seen in Acrobat by selecting File/Document Properties. It is important not to read too much into metadata – if I set up a computer as belonging to Napoleon then PDFs created on that computer by Acrobat would (by default) show Napoleon as the author. And the author, data and other metadata in a document can easily be manipulated. So metadata should be regarded as no more than indicative. of both documents show that they were created by “Bobby” in 2021; we have received reports of the scheme being promoted in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

Both schemes have a fee of 15% of the amounts put into trust.5It looks like GCWealth accept that VAT should be paid on 5%, but then try to argue the remaining 10% is exempt. That is in our view incorrect – it’s all realistically a fee for advice, and VAT therefore applies. That will be a very large amount. If the claim that billions of pounds have gone into these schemes is correct, then over £100m of fees will have been received.

Why the schemes fail

We’ve spoken to leading private client tax advisers, and they believe the claims made in the two documents are fictitious.

The documents say that the taxpayer retains control of his assets at all times, despite the trust arrangement.6The incoherent sentence noticed above (“The trust structure is set up so that the power in the trust to hold the assets are held by the client in a UK new company specifically set up as part of the structure”) also adds to the feeling that this is not a real trust. That suggests that the arrangements may in fact be a “sham“, and there is no trust at all.

But a sham may be the best-case outcome for GCWealth’s clients. If it’s not a sham, the first scheme (the “business asset trust”) won’t be effective, and may trigger large up-front taxes:7This is just a short summary; there are a large number of anti-avoidance rules which may apply here, not least the transfer of assets abroad rules

- The transfer of assets to the trust will likely result in an immediate 20% inheritance tax charge (once beyond the £325k nil rate band). The trust would be subject to a 6% charge every ten years and on any exit of any assets from the trust.

- We’d expect capital gains tax to be triggered on the transfer of assets to the trust unless “hold-over relief” applies. Whether hold-over relief would in principle be available isn’t clear from the description in these documents, but it requires a taxpayer to make a claim to HMRC, and we suspect users of this scheme wouldn’t be minded to tell HMRC about it.

- The client (as settlor) or company (as beneficiary) would ordinarily be subject to capital gains tax on the trust’s capital gains, and the trustee subject to income tax on the trust’s income. We’ve no idea why the document says “any rental stream for the asset is now tax free” and “any sale of the asset is free from CGT”. Possibly there are mechanics behind the scenes that supposedly prevent the usual trust tax rules applying. We are doubtful this is possible in principle8The settlor interested trust rules would seem to apply to tax the income in the hands of the client, as if there had been no trust, but even if it was, we would expect the general anti-abuse rule (GAAR) would apply.9The GAAR doesn’t care about how clever your technical argument is, which is one of the reasons why we are reasonably confident this scheme doesn’t work despite not having access to those technical arguments.

- Where the assets consist of land in England or Northern Ireland10The rules in Scotland and Wales are different; we expect there would be adverse effects, but we have not discussed with Scottish and Welsh tax experts. then the trust’s acquisition of the interest in the assets may trigger a stamp duty land tax charge on the market value of the land.11The deemed market value rule in s53 will apply if the purchaser for SDLT purposes is a connected company. The rules as to who is the “purchaser” in para 3 Sch 16 Finance Act 2003 have the effect that, if the beneficial owner under the trust is the company, then the company is treated as the purchaser. GCWealth’s promotion document suggests that “the beneficial title sits with the client’s own UK new company.” If that is the effect of the documents, then large SDLT liabilities are likely to arise. If the property is residential then the rate could be up to 17%.12i.e. 3% above the normal rate if a company holds the property, and 2% extra if the company/ trust/new owner is treated as non-UK resident for SDLT purposes. The flat 15% rate could apply if an individual dwelling were worth over £500K, although though with reliefs, eg for a property rental business. The non-resident 2% rate applies on-top of the 15% rate.

- Where the assets consist of UK shares13Broadly speaking – it’s a little more complicated than this and (as the document suggests) the beneficiary is a connected company, there will be a stamp duty reserve tax charge equal to 0.5% of the market value of the shares.

- The document says “It does not matter if the asset has borrowing/mortgage. The lender does not need to be notified as the beneficial title of the net equity is transferred to the client’s own UK new company”. We’ve seen these claims before and they are usually false. That’s our view, and also that of the mortgage lenders’ industry body. So, if a mortgaged property is put into trust, the mortgage will probably be defaulted.

We expect the second scheme (the “creditor protection trust”) also fails to provide a tax benefit, and may trigger large up-front taxes:

- The contribution to the trust by the client’s company will be non-deductible for corporation tax purposes, because it isn’t made for wholly and exclusively for the purposes of the company’s trade. Indeed it’s nothing to do with the trade.14Payments to a trust for the benefit of employees are only deductible when and if the employees are taxed on the payments. However that’s only if the payments are deductible on general principles. Here the document goes out of its way to say that the loans “aren’t in any way connected in (sic) the client’s capacity as employee/director of the business”. That is supposed to help the analysis. It doesn’t – but query if it would prevent the company obtaining a deduction, even when (inevitably) the client is taxed on the loan.

- After the most recent wave of attempts to avoid employment tax, the “disguised remuneration” rules were introduced. If you are a director, and receive what is in substance a reward, via a third party, then you get taxed. These rules will apply here.15The claim that “The loan is taken by the client in his capacity as a creditor to the trust (ie not in any way connected in the client’s capacity as employee/director of the business)” is presumably an attempt to avoid these rules, but it is obviously untrue. Of course the loan is connected to the client’s capacity as a director – the company only made the contribution to the trust because the client/director knew he would receive it back as a loan. Possibly there are mechanics intended to defeat the disguised remuneration rules16Which may mean it falls within the DOTAS employment income hallmark – see 5.8 – it is not obvious how even in principle this could be achieved but, even if it was, we expect the GAAR would apply, as it already has to another variant on a remuneration trust structure.

- Realistically, the contributions to the trust by the company are gifts. We expect they will be subject to a 25%17In such a case, the usual 20% rate is grossed-up to 25%. inheritance tax entry charge in the hands of the company’s shareholders (beyond the £325k nil rate band).18Assuming the company is close, which seems likely. More details here, with an example here.

Both schemes end up being a tax disaster for GCWealth’s clients.

Failure to disclose the scheme

DOTAS

Tax avoidance schemes are required to be disclosed to HMRC under the DOTAS rules. Given that the two GCWealth schemes have a main benefit of creating a tax advantage, and there is a 15% fee, it is in our view reasonably clear that the schemes should have been disclosed. We asked GCWealth on three occasions if they disclosed and they failed to answer. We therefore believe that GCWealth unlawfully failed to disclose.

Where an offshore promoter fails to disclose a scheme, the clients themselves are required to disclose. The promoter can also be subject to penalties of up to £1m.

IHTA return

There is a special reporting rule that applies to anyone who, in the course of their trade/profession, is involved in the creation of an offshore trust for a UK settlor, but inheritance tax isn’t paid when the trust is established.

We expect no inheritance tax was paid on the establishment of these trust structures, which means that this rule will have applied, and a return should have been made to HMRC. We doubt that it was.19The penalties for a breach of section 218 are ludicrous – £300 plus £60/day. It is, however, unacceptable for a solicitor to ignore a legal requirement.

Other registration rules

Any offshore trust/settlement owning UK real estate is required to register with the Trust Registration Service. Does GCWealth register its trusts?

Offshore entities with beneficial ownership of land in England & Wales are required to register with the Register of Overseas Entities. Does GCWealth do this?

Tax avoidance or fraud?

There are a number of signs that the promoter either has no understanding of tax, or is engaged in a deliberate deceit:

- The claim that this is “not a tax avoidance scheme” is laughable. The only purpose of this arrangement is to avoid tax and other legal obligations.

- The first document (“business asset trust”) says that “HMRC are bound by the validity of the structure”. They are clearly not, and we don’t believe any competent lawyer or tax adviser would think otherwise.

- The second document (“creditor protection trust”) says that “HMRC accept the validity of the structure”. Either HMRC have been shockingly negligent, or this is a lie.

- The description in the second document says “the client will also be a beneficiary to the trust ie a creditor”. A beneficiary is not a creditor. Perhaps this is a deliberate attempt to muddy the waters, or perhaps the author does not understand trusts.

- The documents claim that “The very nature of the structure means that it is not subject to the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR)”. The GAAR guidance contains numerous examples of the GAAR applying to trusts and the GAAR advisory panel has issued a decision on an offshore remuneration trust structure. Why wouldn’t the GAAR apply to these variants? And any tax adviser knows it is the general anti-“abuse” rule.

- We see no proper basis for a DOTAS disclosure not being made.

- We are confident HMRC would challenge these schemes if it became aware of them (and we are aware of one case where HMRC did become aware and did challenge). But the way the first scheme works, with a “silent” trust that operates behind the scenes, means that it will be very hard for HMRC to discover the existence of the schemes unless they are properly disclosed in tax returns. We expect that scheme users do not properly disclose the scheme, with either no disclosure or misleading disclosure. Deliberate concealment is potentially tax fraud.

How much have these schemes cost taxpayers?

GCWealth says that the structure has “Protected several £Billion wealth since 2009” and that their clients includes “business owners in every major industry sector; some of the UK’s wealthiest families; some of the UK’s leading sportspeople; property developers and investors”.

We don’t know if these claims are true. But if they are, we expect that the schemes have resulted in a cost to the taxpayer of around £1bn, thanks to GCWealth’s clients having failed to pay tax that in our opinion was legally due.

Divorce protection

GCWealth claims the first scheme, the “business asset trust” means your “assets protected from 50/50 split upon divorce”. It’s a variant of the “deed in the drawer” structure that’s been used for centuries. As one judge recently summarised it:

“The phenomenon of the “deed in the drawer” is one that is now frequently encountered. X appears to be the owner of a property, and people lend to him or otherwise deal with him on the footing that he owns it. But if X becomes bankrupt or the subject of enforcement proceedings a deed is produced which shows that in truth he holds the property upon trust for somebody else. In some cases these deeds are simply not authentic. In other cases they are authentic, but simply not noted in any public register.”

We spoke to barristers and solicitors specialising in chancery law, family law, and nuptial agreements, and they all expected the trust would fail to achieve this:

- As noted above, it could be attacked as a sham on conventional Chancery principles (because in a real trust the settlor does not have full control of the assets).

- If not a sham, the fact the client has control of the assets suggests that it is simply the “property and other financial resources“20The courts have found trusts to be “other financial resources” in numerous cases of “real” trusts where the settlor influences the trustees, but does not have complete control. The test in Charman v. Charman [2006] 1 WLR 1053 is “whether, if the husband were to request [the trustee] to advance the whole (or part) of the capital of the trust to him, the trustee would be likely to do so”. of the client, and part of the “matrimonial pot” in the same way as any other asset. The arrangement achieves nothing.

- If not a sham and the client somehow doesn’t have influence/control, the question is whether the trust was created “with an intention to defeat” the spouse’s financial claims. If it was, then the court could make an order to set it aside under section 37 of the Matrimonial Causes Act. There is a rebuttable presumption that the trust was created with such an intention if it was created less than three years before the date of the court application. Even after three years21Note that if there is sufficient evidence then there is no limitation period for s37. the experts we spoke to thought that the structure was plainly motivated by a desire to defeat a claim for financial relief, and therefore it would be hard to resist a section 37 order.22i.e. because the divorce “advantage” is specified in the promotional material for the trust, and further evidence would likely emerge from disclosure (including the client’s correspondence with GCWealth. Indeed it is unclear what purpose the client could say the trust had, other than tax avoidance and “asset protection”..

The specialists we spoke to concluded from this, and the incorrect reference to the “50/50 split”, that the promoters of the scheme have no expertise in this area and did not take appropriate advice.23There is one an additional point that probably isn’t relevant, but some arrangements of this kind get caught by. If the wife were a beneficiary of the trust, even to a small amount, that the trust could qualify as a “nuptial settlement”, which the court has almost unlimited powers to vary.

Insolvency protection

The documents also promise that the trusts mean your assets are “immediately sheltered from bankruptcy, insolvency proceedings”. This claim is false.

Gifts into a trust will be set aside if made within two years of your bankruptcy, or five years if you were insolvent at the time. And a gift made at any time can be set aside if a court is satisfied that the gift was made for the purpose24Such an improper purpose will exist even if there are other purposes, such as tax avoidance. of putting assets beyond the reach of a person who is making, or may at some time make, a claim against him. 25The Lemos judgment provides a useful example of how the courts apply section 423 in practice.

The confidence with which a clearly incorrect claim is made again suggests that the promoters have no expertise and did not take appropriate advice.

Bobby Gill

The man behind these companies is a British solicitor called Bobby Gill.26Gill tells us he doesn’t own GCWealth Administrators Limited but is merely a consultant. The reports we’ve received of GCWealth’s sales efforts only mention Gill. Gill clearly was the owner of GCWealth’s predecessor UK company (of which more below), which appears to have transferred its business to the Belize operations. Obfuscation of ownership is a common tactic of tax avoidance scheme promoters.

Gill says he’s “been a leading international corporate lawyer for over 2 decades”. He is indeed a solicitor (non-practising) but, whilst we have extensive contacts in international and offshore law firms, we couldn’t find anybody who’s heard27Aside from the Swisspro High Court case we mention below. of him.28Gill says that, until 2009, he was an associate at Allen & Overy and Mallesons in Sydney, and then a partner at an unspecified top 20 international law firm. The internet has no evidence of any of this, although companies House suggests that from 2006 to 2010 Gill worked for a boutique law firm called iLaw. He has no web presence except amateur looking Wix and WordPress sites, and what look like paid-for profile pieces on obscure websites.29An obvious caveat is that we cannot know whether Gill actually created these pages or someone else did; it is, however, difficult to see what motive anyone other than Gill would have to write them. Gill may have been conned by one of the firms like Mogul Press that promise to raise their clients’ profiles, but actually just publish poorly written articles on low impact websites.

Gill’s sole public visibility arises from his ownership of a business called Swisspro Asset Management AG30There was also a UK company, Swisspro Asset Management AG Limited, owned by Gill, which appears to have been dormant – if we can trust the accounts. And a Canadian company, Swisspro Asset Management Inc, which was dissolved in 2022 for non-compliance after failing to file any accounts since its incorporation in 2017. which attracted investors on the basis it would undertake currency trading and pay them a 2% per month fixed return (which equates to a 27% annualised return). We’ve spoken to FX traders and fund managers – none regard this as plausible.

Swisspro became insolvent in 2019, as did a related UK funding entity called GCW Funding Limited. The Swiss financial regulator issued a “cease and desist” order to Gill, requiring him to cease accepting investments (machine translated version here). According to Bloomberg, the Swiss regulator said in a letter to creditors that the business “appears a Ponzi scheme”. Ordinary investors lost large sums.

Gill gave a personal guarantee for £1.5m borrowed by Swisspro.31Which suggests Swisspro wasn’t originally established as a fraudulent enterprise. Swisspro started to get into financial difficulties in 2017 and the lender called on the loan in 2018. Gill tried to argue that, because the guarantee had been signed electronically, he wasn’t bound by it. The dispute ended up at the High Court, which wasn’t impressed with Gill’s attempt to escape the guarantee he’d signed.

It’s hard to understand why Gill ever thought his business could produce such high returns for investors. He told us that the failure was the fault of an FX trader engaged by Swisspro, who has since been convicted for fraud and money laundering and is currently an international fugitive.32Gill continued “There is an ongoing police investigation, and me, my family and many others are victims of this fraud. I have assisted the police to the best of my abilities and been praised for my support and assistance. I am unable to comment much further on this given the ongoing investigations”. That doesn’t explain why Gill made the claim of a 2% return per month, or why he continued to take customer money well after the point that Swisspro was unable to repay the £1.5m loan.

As a non-practising solicitor, Gill remains bound by SRA rules which prohibit solicitors from promoting aggressive tax avoidance schemes. We have reported Gill to the SRA.

GCWealth

GCWealth has no online presence (the similarly named company that does is completely unrelated). It reaches clients and wealth advisors through direct sales.

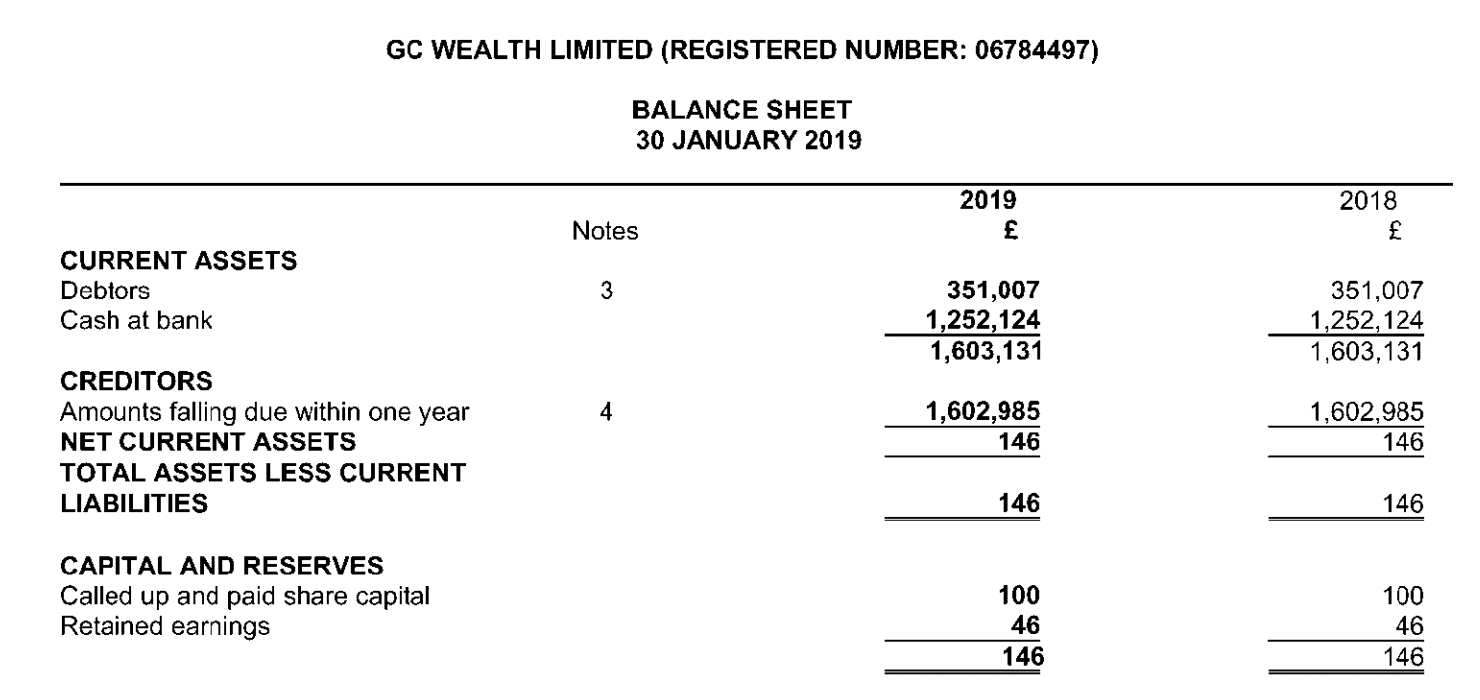

Gill established GC Wealth Limited as a UK company, and in 2016-2018 it had significant fee income. But its accounts for 2019 appear to be badly wrong, with the 2019 balance sheet identical, to the pound, to the 2018 balance sheet:

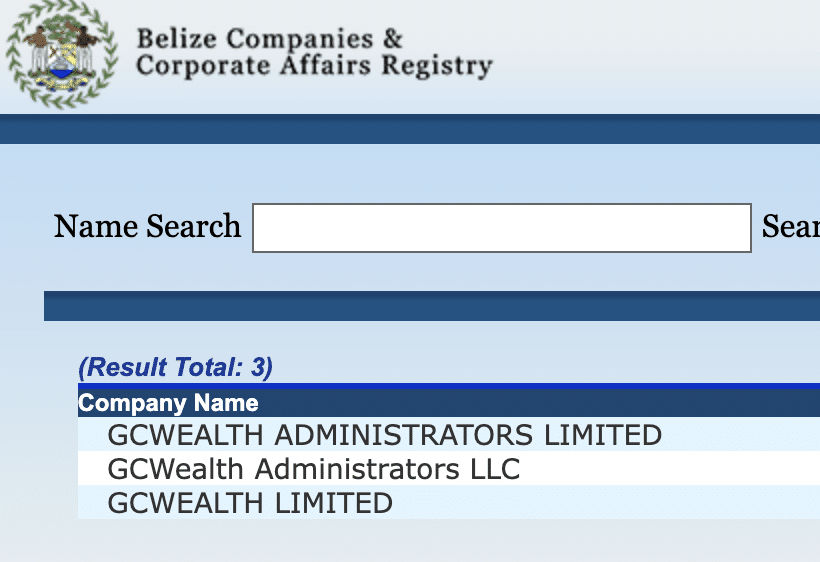

It also looks as those there may have been aggressive tax avoidance to prevent the company’s profits being taxed.33This is on the basis of the 30 January 2019 balance sheet, which show £1,252,124 cash at bank, £351,007 debtors, and almost all of that (£1,602,985) owed to creditors (of which HMRC account for only £11). The figures in the 30 January 2018 balance sheet are exactly the same, to the pound, which the accountants we spoke to thought was likely a bad mistake (it is just about possible in principle for a company with so much cash to have no balance sheet movements at all from one year to the next, but none of the experienced accountants we spoke to had ever seen such a thing). The 30 January 2020 accounts then show the 2019 balance sheet as all zeroes, but there was no filing of amended accounts, and no explanation for the change, so this appears to be another error or a rewriting of history rather than a proper correction in accordance with usual accounting practice.34The 30 January 2017 balance sheet shows £2,250,066 cash in bank, £119,563 debtors, and almost all of that (£2,369,529) owed to creditors (none owed to HMRC). On the basis of these accounts, and what we know of the GCWealth scheme, we would speculate that the company made offshore payments it claimed to be tax-deductible. The accounts of other Gill companies, GCW Funding Limited, GCW Funding (2) Limited and GC Wealth RT Limited have similar features, with GC Wealth RT Limited also having a 2019 balance sheet identical to the 2018 balance sheet. At some point around 2019 that company became dormant and the business moved to “GCWealth Administrators Limited” and two associated companies in Belize:

Has the scheme been challenged?

One client sued Gill and his associated companies for negligence back in 2018. We don’t know the outcome, but infer from the lack of action that it was settled. There was another case against Gill around the same time; we don’t know what it involved.

There are signs that HMRC is aware of GCWealth’s activities. We believe there is one live case where HMRC is challenging a UK taxpayer who used a GCWealth scheme. And HMRC applied at the end of last year to wind up GCWealth RT Limited (but we don’t know why, or what that company did35Although “RT” often stands for “remuneration trust”).

However, Gill and GCWealth are not on HMRC’s list of named promoters and avoidance schemes, and aren’t subject to a “stop notice” making promotion a criminal offence. They should be.

Links to other schemes

Bobby Gill appears to be connected to notorious tax avoidance scheme promoter Paul Baxendale-Walker.36One of the defendants in the negligence case brought against Gill was Bay Trust International Limited, which linked to Baxendale-Walker. There is another case involving Gill and two of Baxendale-Walker’s Minerva and Buckingham companies. And another case in which Gill applied to set aside a statutory demand; his lawyers were Morr & Co, who often act for Baxendale-Walker and his companies. We understand that Gill used to sell PBW remuneration trust schemes, and the trust schemes described in this article are very similar to PBW structures. We do not know if this is coincidence, if PBW helped create the schemes or if Gill just copied/modified existing PBW structures.37We put to Gill that he was connected to PBW. His response was that he “repeated his comments above”. It’s not clear which comments he refers to, so this may or may not be a denial.

There also a surprising connection to the OneCoin Ponzi fraud we covered earlier this year, through the “C” in “GC Wealth” – a lawyer called Robert Courtneidge. Gill’s original UK company was once called Gill & Courtneidge Wealth Limited (although Courtneidge no longer appears directly involved), and Courtneidge was described by the High Court as a friend of Gill. Courtneidge was a lawyer to the OneCoin Ponzi fraud and has been associated with other failed businesses (although he has not been accused of any wrongdoing).

The other individual known to have been involved in GCWealth is a woman called Marianna Timmini. We don’t know anything about her.

We are working on an application that will visualise connections between individuals linked to UK companies – it’s not quite ready for public consumption, but the GCWealth connections look like this:

Bobby Gill’s response

Gill sent us a response in which he said “The company has never engaged in any form of ‘tax avoidance’, aggressive or not. Indeed it has never engaged in any form of tax planning.”

We view that as completely untrue. The trusts have no purpose other than to avoid tax and hide assets from creditors or a spouse. We believe any reasonable tax adviser would see this as highly aggressive tax avoidance. 38There is no single legal definition of “tax avoidance”, but tax advisers and judges know it when they see it.

We put to Gill that the structure was technically hopeless. His response was that we’d only seen two page summaries. In many cases that would be a fair criticism: it would be unwise to judge the efficacy of (for example) Google’s tax structure, or the Duke of Westminster’s inheritance tax planning, on the basis of a two page summary. However just as a physicist would feel confident dismissing a miraculous perpetual motion machine on the basis of a two page summary, we feel reasonably confident dismissing a scheme that achieves the fiscal miracle of nullifying all tax from an asset.39If you are sceptical of this claim, have a look through decided cases where the first paragraph of the judgment describes the arrangement in question as a “tax avoidance scheme”. In the last 25 years, the result has almost always been that the taxpayer loses. We have also seen correspondence between Gill and advisers acting on behalf of people interested in the GCWealth schemes. The pattern is always the same: when advisers ask technical questions, Gill stops responding to emails.

We asked Gill three times if the trusts had been disclosed under DOTAS. He avoided answering directly, but instead said HMRC were aware of the trusts,. That is not the same thing. The requirement to notify HMRC of a tax avoidance scheme applies regardless of whether HMRC are “aware” of the scheme.40That not’s quite true for SDLT, where a scheme that’s been around for ages, and HMRC are therefore aware of, can in some cases be “grandfathered” and not subject to DOTAS notification. We infer from Gill’s response that no DOTAS notification has been made. And that’s what we’d expect for this kind of scheme – marketing it is much more difficult if it’s been disclosed to HMRC as a tax avoidance scheme.

We set out our correspondence with Gill in full here.

How can these schemes be stopped?

We have three recommendations:

First, use and expand existing powers

HMRC needs to be more proactive identifying and naming schemes. We believe HMRC is aware of the GCWealth scheme. Why isn’t it on HMRC’s published list of avoidance schemes?

When schemes are put on the list, it’s only for twelve months. That’s a silly limitation of current law – the law should be changed.

Second, make it a criminal offence to fail to disclose avoidance schemes

One constant in all the tax avoidance schemes we see is that none are disclosed to HMRC under DOTAS, the rules requiring notification of tax avoidance schemes. The technical basis for this is either non-existent or nonsensical. The real rationale is that nobody can sell an avoidance scheme that’s been disclosed under DOTAS

This needs to change.

It should be a criminal offence to fail to disclose a scheme under DOTAS where no reasonable adviser would have thought there was a reasonable basis for failing to disclose.41In other words, borrow the successful “double reasonableness test” from the GAAR It would be important for HMRC to make clear that the offence would never be applied to a genuine mistake; the measure would be a failure if it concerned normal tax advisers. The offence should be carefully calibrated to only impact the cowboys, and there should be a defence where the breach occurred despite a person taking reasonable steps to comply with DOTAS.42So, for example, if a person relies on an opinion from an adviser that DOTAS doesn’t apply then the defence should be available. If, however, the opinion was obtained on the basis of incorrect assumptions of fact, the adviser was improperly briefed, or a reasonable layperson would suspect the opinion was incorrect (e.g. because the barrister had previously issued opinions on DOTAS which courts had found to be incorrect), then the defence would not be available.

Third, end the offshore promoter loophole

Many of HMRC’s powers are hard to enforce against offshore promoters of tax avoidance schemes. Obtaining an offshore promoter’s client lists and documentation is, for example, very difficult.

Tax avoidance scheme promoters have taken ruthless advantage of this by moving their businesses offshore. We would speculate that this is why Gill moved his GC Wealth business from the UK to Belize in 2018.

The obvious solution is to simply prohibit offshore entities from promoting tax avoidance schemes (broadly defined), with criminal penalties for breach, and enhance penalties for taxpayers using such schemes.

Many thanks to all the experts who contributed to this report, including: O, M and James Quarmby (personal tax), Elis Gomer (chancery law), S (SDLT and general technical review), N (divorce law), K (insolvency law), C and P (accounting), E (additional research) and O, F and B for their FX and fund management insights. As is always the case, Tax Policy Associates Ltd takes sole responsibility for the content of the report.

Documents © GCWealth Administrators Limited, and reproduced here in the public interest and for purposes of criticism and review.

- 1The document actually says that “the beneficial title sits” with the company. That can’t be right, because it implies the arrangement is a bare trust, which would have no tax effect. Probably the author doesn’t understand the difference between a beneficiary and beneficial title.

- 2The document expressly says the company is the beneficiary of the trust. But it also says, in the previous sentence: “The trust structure is set up so that the power in the trust to hold the assets are held by the client in a UK new company specifically set up as part of the structure, of which the client is the sole shareholder and director” which is incoherent, but perhaps suggests the company manages the trust?

- 3These steps sometimes include an intermediate non-UK company which acquires the asset and makes the contribution to the trust. This appears to be an attempt to fool UK settlement rules – it won’t work.

- 4Metadata is the data created when by software that creates or edits documents, but which is not visible onscreen when you view the document. The metadata in a PDF file can, for example, be seen in Acrobat by selecting File/Document Properties. It is important not to read too much into metadata – if I set up a computer as belonging to Napoleon then PDFs created on that computer by Acrobat would (by default) show Napoleon as the author. And the author, data and other metadata in a document can easily be manipulated. So metadata should be regarded as no more than indicative.

- 5It looks like GCWealth accept that VAT should be paid on 5%, but then try to argue the remaining 10% is exempt. That is in our view incorrect – it’s all realistically a fee for advice, and VAT therefore applies.

- 6The incoherent sentence noticed above (“The trust structure is set up so that the power in the trust to hold the assets are held by the client in a UK new company specifically set up as part of the structure”) also adds to the feeling that this is not a real trust.

- 7This is just a short summary; there are a large number of anti-avoidance rules which may apply here, not least the transfer of assets abroad rules

- 8The settlor interested trust rules would seem to apply to tax the income in the hands of the client, as if there had been no trust

- 9The GAAR doesn’t care about how clever your technical argument is, which is one of the reasons why we are reasonably confident this scheme doesn’t work despite not having access to those technical arguments.

- 10The rules in Scotland and Wales are different; we expect there would be adverse effects, but we have not discussed with Scottish and Welsh tax experts.

- 11The deemed market value rule in s53 will apply if the purchaser for SDLT purposes is a connected company. The rules as to who is the “purchaser” in para 3 Sch 16 Finance Act 2003 have the effect that, if the beneficial owner under the trust is the company, then the company is treated as the purchaser. GCWealth’s promotion document suggests that “the beneficial title sits with the client’s own UK new company.” If that is the effect of the documents, then large SDLT liabilities are likely to arise.

- 12i.e. 3% above the normal rate if a company holds the property, and 2% extra if the company/ trust/new owner is treated as non-UK resident for SDLT purposes. The flat 15% rate could apply if an individual dwelling were worth over £500K, although though with reliefs, eg for a property rental business. The non-resident 2% rate applies on-top of the 15% rate.

- 13Broadly speaking – it’s a little more complicated than this

- 14Payments to a trust for the benefit of employees are only deductible when and if the employees are taxed on the payments. However that’s only if the payments are deductible on general principles. Here the document goes out of its way to say that the loans “aren’t in any way connected in (sic) the client’s capacity as employee/director of the business”. That is supposed to help the analysis. It doesn’t – but query if it would prevent the company obtaining a deduction, even when (inevitably) the client is taxed on the loan.

- 15The claim that “The loan is taken by the client in his capacity as a creditor to the trust (ie not in any way connected in the client’s capacity as employee/director of the business)” is presumably an attempt to avoid these rules, but it is obviously untrue. Of course the loan is connected to the client’s capacity as a director – the company only made the contribution to the trust because the client/director knew he would receive it back as a loan.

- 16Which may mean it falls within the DOTAS employment income hallmark – see 5.8

- 17In such a case, the usual 20% rate is grossed-up to 25%.

- 18Assuming the company is close, which seems likely. More details here, with an example here.

- 19The penalties for a breach of section 218 are ludicrous – £300 plus £60/day. It is, however, unacceptable for a solicitor to ignore a legal requirement.

- 20The courts have found trusts to be “other financial resources” in numerous cases of “real” trusts where the settlor influences the trustees, but does not have complete control. The test in Charman v. Charman [2006] 1 WLR 1053 is “whether, if the husband were to request [the trustee] to advance the whole (or part) of the capital of the trust to him, the trustee would be likely to do so”.

- 21Note that if there is sufficient evidence then there is no limitation period for s37.

- 22i.e. because the divorce “advantage” is specified in the promotional material for the trust, and further evidence would likely emerge from disclosure (including the client’s correspondence with GCWealth. Indeed it is unclear what purpose the client could say the trust had, other than tax avoidance and “asset protection”.

- 23There is one an additional point that probably isn’t relevant, but some arrangements of this kind get caught by. If the wife were a beneficiary of the trust, even to a small amount, that the trust could qualify as a “nuptial settlement”, which the court has almost unlimited powers to vary.

- 24Such an improper purpose will exist even if there are other purposes, such as tax avoidance.

- 25The Lemos judgment provides a useful example of how the courts apply section 423 in practice.

- 26Gill tells us he doesn’t own GCWealth Administrators Limited but is merely a consultant. The reports we’ve received of GCWealth’s sales efforts only mention Gill. Gill clearly was the owner of GCWealth’s predecessor UK company (of which more below), which appears to have transferred its business to the Belize operations. Obfuscation of ownership is a common tactic of tax avoidance scheme promoters.

- 27Aside from the Swisspro High Court case we mention below.

- 28Gill says that, until 2009, he was an associate at Allen & Overy and Mallesons in Sydney, and then a partner at an unspecified top 20 international law firm. The internet has no evidence of any of this, although companies House suggests that from 2006 to 2010 Gill worked for a boutique law firm called iLaw.

- 29An obvious caveat is that we cannot know whether Gill actually created these pages or someone else did; it is, however, difficult to see what motive anyone other than Gill would have to write them. Gill may have been conned by one of the firms like Mogul Press that promise to raise their clients’ profiles, but actually just publish poorly written articles on low impact websites.

- 30There was also a UK company, Swisspro Asset Management AG Limited, owned by Gill, which appears to have been dormant – if we can trust the accounts. And a Canadian company, Swisspro Asset Management Inc, which was dissolved in 2022 for non-compliance after failing to file any accounts since its incorporation in 2017.

- 31Which suggests Swisspro wasn’t originally established as a fraudulent enterprise.

- 32Gill continued “There is an ongoing police investigation, and me, my family and many others are victims of this fraud. I have assisted the police to the best of my abilities and been praised for my support and assistance. I am unable to comment much further on this given the ongoing investigations”.

- 33This is on the basis of the 30 January 2019 balance sheet, which show £1,252,124 cash at bank, £351,007 debtors, and almost all of that (£1,602,985) owed to creditors (of which HMRC account for only £11). The figures in the 30 January 2018 balance sheet are exactly the same, to the pound, which the accountants we spoke to thought was likely a bad mistake (it is just about possible in principle for a company with so much cash to have no balance sheet movements at all from one year to the next, but none of the experienced accountants we spoke to had ever seen such a thing). The 30 January 2020 accounts then show the 2019 balance sheet as all zeroes, but there was no filing of amended accounts, and no explanation for the change, so this appears to be another error or a rewriting of history rather than a proper correction in accordance with usual accounting practice.

- 34The 30 January 2017 balance sheet shows £2,250,066 cash in bank, £119,563 debtors, and almost all of that (£2,369,529) owed to creditors (none owed to HMRC). On the basis of these accounts, and what we know of the GCWealth scheme, we would speculate that the company made offshore payments it claimed to be tax-deductible. The accounts of other Gill companies, GCW Funding Limited, GCW Funding (2) Limited and GC Wealth RT Limited have similar features, with GC Wealth RT Limited also having a 2019 balance sheet identical to the 2018 balance sheet.

- 35Although “RT” often stands for “remuneration trust”

- 36One of the defendants in the negligence case brought against Gill was Bay Trust International Limited, which linked to Baxendale-Walker. There is another case involving Gill and two of Baxendale-Walker’s Minerva and Buckingham companies. And another case in which Gill applied to set aside a statutory demand; his lawyers were Morr & Co, who often act for Baxendale-Walker and his companies.

- 37We put to Gill that he was connected to PBW. His response was that he “repeated his comments above”. It’s not clear which comments he refers to, so this may or may not be a denial.

- 38There is no single legal definition of “tax avoidance”, but tax advisers and judges know it when they see it.

- 39If you are sceptical of this claim, have a look through decided cases where the first paragraph of the judgment describes the arrangement in question as a “tax avoidance scheme”. In the last 25 years, the result has almost always been that the taxpayer loses.

- 40That not’s quite true for SDLT, where a scheme that’s been around for ages, and HMRC are therefore aware of, can in some cases be “grandfathered” and not subject to DOTAS notification.

- 41In other words, borrow the successful “double reasonableness test” from the GAAR

- 42So, for example, if a person relies on an opinion from an adviser that DOTAS doesn’t apply then the defence should be available. If, however, the opinion was obtained on the basis of incorrect assumptions of fact, the adviser was improperly briefed, or a reasonable layperson would suspect the opinion was incorrect (e.g. because the barrister had previously issued opinions on DOTAS which courts had found to be incorrect), then the defence would not be available.

14 responses to “GC Wealth – the £bn tax avoidance scheme that could be fraud”

also a victim – folks should look further at ultra limited – Graham Holtby , Gill wealth ( Bobbys Brother Mavinder – or Mike – or Devinder ) also part of the group – onshore folks although believe Bobby not onshore at all these days from my research

Hi Graham how so a victim

I am a victim of Bobby Gill. He promoted his FX trading opportunity to me – in September 2016. I went to a mystery shopper seminar as a high net worth person interested in a remuneration trust. Also participated in the FX investment and lost money.

Gill hid it offshore and that is why the police can’t nail him to the wall.

Hopefully his life will be increasingly reclusive and that will be the punishment. His children will know his crimes. He will find it harder to move in normal society because he will eventually be held to account.

I was a victim of Bobby Gill’s FX scam. The man is scum – qualified legal professional scum – he knows exactly what he has done. He engaged David Affleck (Wotton Bassett) and Peter Thomas (Douglas, Isle of Man) to hide the funds and claims he was also scammed. He refused to answer questions years ago when it all fell apart. Honest men do not behave like that. He is a serial scumbag. And Robert Courtneidge has his name all over the remuneration trust entity and the set up of the FX entity. Why would highly qualified professionals – who used their credentials to lure investors in – now be credible when they plead ignorance? Shame on the SRA for insisting that they will wait for the police before striking them off. The police will take years – if they ever get sentences – they are focused on Anthony Constantinou who is referred to as the rogue FX trader. They all played their part and they will all take their seats in hell for what they have done.

The explanatory note suggests that the asset is transferred by the original owner to a Belize trust of which the beneficiary is a UK company owned by the original owner. If the Belize trust is a bare trust, then there would indeed be no disposal for CGT or IHT purposes. Equally, the original owner would, in my view, be treated as the owner for IHT and CGT purposes, so there is no advantage to him. In matrimonial or insolvency proceedings, I suspect he would be obliged legally to disclose the whole arrangement and the court would consider the asset his. If the Belize trust is otherwise that a bare trust, then there is a disposal but, in my view, the original owner is settlor for UK tax purposes, by having provided the funds. It looks as if the whole arrangement is either ineffective or relies on simple non-disclosure.

thanks, Michael. The document does suggest a bare trust but I think that’s just because the author is either hiding things or clueless. Much more likely it’s a settlement given that’s how these kinds of magical offshore trusts usually work. But, as you say, that runs into a whole bunch of issues…

This article goes a long way to addressing my doubt about your repeated assertion that the small business tax gap is bigger than the large business tax gap.

I was thinking that the small business tax gap was about things like putting through some personal expenses in a business, which even for 100 times more companies, pales next to MNCs putting profits in Ireland/Cayman etc

This sort of “scheme”, an evasion of tax for substantially a whole business, is beyond what I was imagining.

Thanks! Yes, it does seem likely that much or even most of the small business tax gap is nothing to do with normal small business activities…

I feel Govt needs to police direct and disguised corruption in public departments. The existence of such platform promoting illegal activities puts pressure on honest and hard working professionals. All the legislative control seems to be directed to the wrong set of professionals and the real culprits are free to roam around. The govt must provide a way out of these schemes by voluntary disclosure and de-enveloping the assets to its original rightful place. Such a disclosure will bring in much needed revenues for the past x number of years in a single go. it will normalize the unsettled assets. The promotors of such scheme should be punished with criminality and confiscation orders must be used.

I don’t see any evidence that this has anything to do with corruption with in public departments.

Is Bobby Gill in any way related to David Gill?

I can only imagine how many reputable accountants and private wealth advisers are accused of not being aggressive enough and are fired by their greedy clients. All so the clients can say “Hey Bobby” to a man in Belize.

Great work Dan but the big questions are why it falls to you to more widely publicise such schemes and why aren’t HMRC addressing these schemes earlier and more robustly or securing legislative changes to prevent them.

Excellent body of work. My initial reaction to this scheme as it was being set out was how similar to a BW fidco/offco scheme this was. You draw that comparison later on in the paper.