The Lib Dem manifesto is here, and a separate costings document is here. It claims to raise £27bn from tax increases. There is very little detail, but five items seem questionable, representing over £9bn in total:

First, the Lib Dems propose to raise £1.4bn from a tax on share buybacks. But the tax is badly flawed and likely will raise little or nothing.

Second, the Lib Dems propose to raise £5.2bn by increasing capital gains tax. But historically it has been a mistake to pre-announce a rise in capital gains: people sell early and make gains before the rise comes into effect. In 1988 this resulted in the rise yielding no net revenue. The same may happen here.

Third, the Lib Dems plan to raise £2.1bn by tripling the digital services tax. Digital Services Taxes are currently at a difficult moment. The OECD initiative that was supposed to replaced them has stalled. An agreement between the UK, United States and others (which would prevent any increase) expires at the end of this month. Unilaterally tripling the rate when the agreements expires is certainly possible, but likely to be seen as provocative by the US administration.

Fourth, The Tories said they will raise £6bn by clamping down on avoidance. Labour says they can raise £5bn. Both parties ramp up to these figures over the course of a Parliament, with Labour booking only £700m of revenue in the first year. The Lib Dems seem to expect to book £7.2bn every year, with no ramping up. That looks like a mistake. They have also (unlike the other two parties) provided no details on how they would achieve this.

Fifth, the manifesto says the Lib Dems will end the loan charge. This was a controversial anti-avoidance measure that raised about £3.2bn in total. Are the Lib Dems saying they’ll refund that? If they are, why isn’t it in their costings? And if not, what does this proposal mean?

We set out the issues in more detail below.

The overall tax effect of the manifesto

We have previously said that the tax increases that Labour and the Conservatives were arguing about were so small as to be irrelevant.

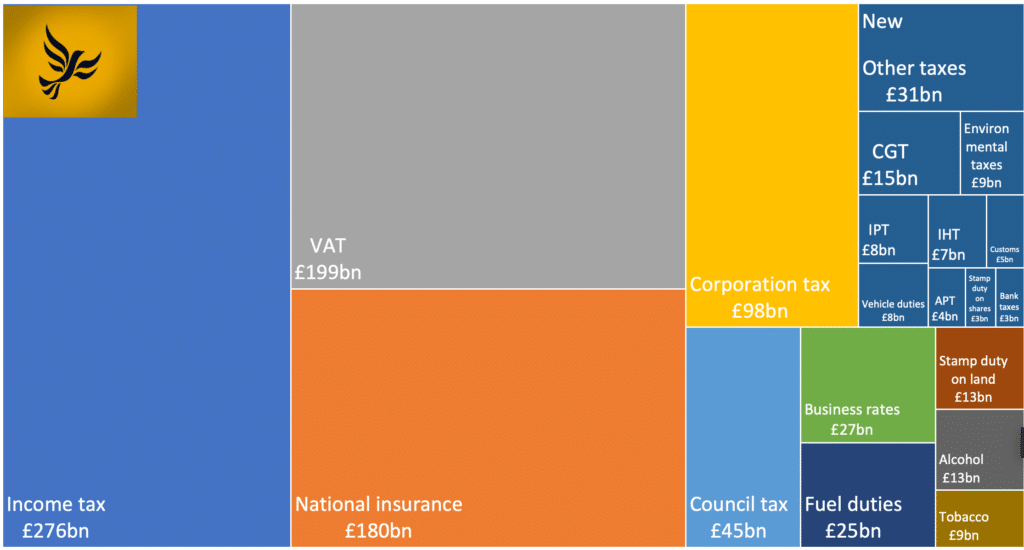

The Lib Dems’ £27bn of tax increases is still small in the context of total UK tax revenues, but not insignificant.

This chart superimposes the size of the Lib Dem tax increases over all the figures for UK tax receipts in 2023/24 (and, for ease, it’s in the top left, but none of the Lib Dem increases are to income tax):

Capital gains tax – £5.2bn

The Lib Dems plan to significantly increase the current rate of capital gains tax:

“Fairly reform Capital Gains Tax: Close loopholes exploited by the super-wealthy by adjusting the rates and basing them solely on capital gains while increasing the tax-free allowance from £3,000 to £5,000, on top of a new tax-free allowance for inflation, and introducing a relief for small businesses.”

That’s not very specific, but their press release (not publicly available) said:

“New rate of 40% for gains of between £50,000 to £100,000, and 45% for gains of over £100,000.”

The Lib Dems say this will raise £5.2bn, but there’s no breakdown on the additional revenues from increasing the rate, the lost revenue from indexation allowance/reliefs and the cost of increasing the allowance.

There is a good argument for raising CGT. Having so great a gap between income and capital gains enables avoidance, as people flip what would otherwise be income (taxed at 39.35% or even 47%) into capital gains (usually taxed at 20%). There is also a good argument for reintroducing an allowance for inflation.

But there is a significant, albeit rather unfair, problem with this proposal.

Schrodinger’s tax increase

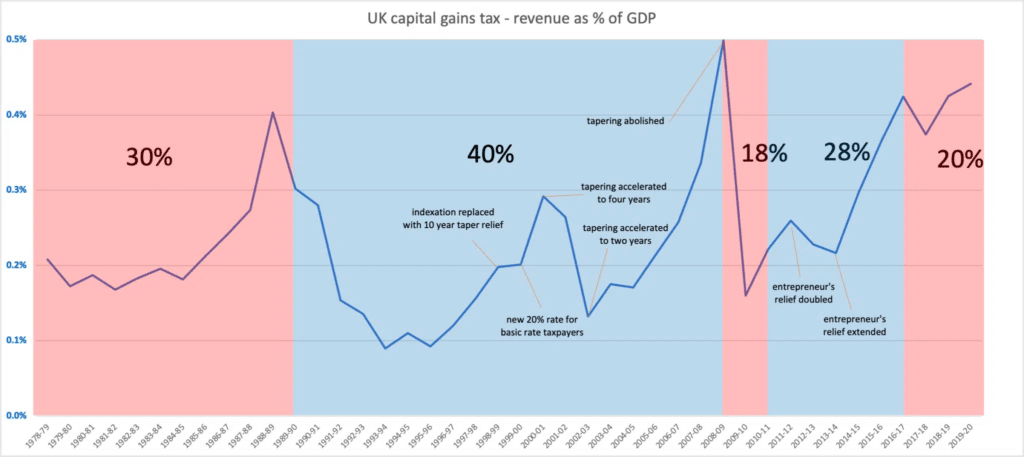

On 15 March 1988, Nigel Lawson announced he would increase the rate of CGT to 40% and introduce an indexation allowance. That was, I think, a good idea.

However the new rate applied from 6 April 1988. In the intervening three weeks we saw a lot of share sales, as people “crystallised” their historic gains under the 30% rate whilst they still could.

That resulted in a significant increase in CGT revenues before the change came in, and a significant decline afterwards:

Taking both factors into account, in the next five years following the announcement, the rate increase raised no additional revenue.

If the Lib Dems win the election (or form part of a coalition) then the Budget would likely be in the following Autumn. People would have rather longer than two weeks to crystallise gains. We could expect to see a similar, or larger, effect again (particularly with shares).

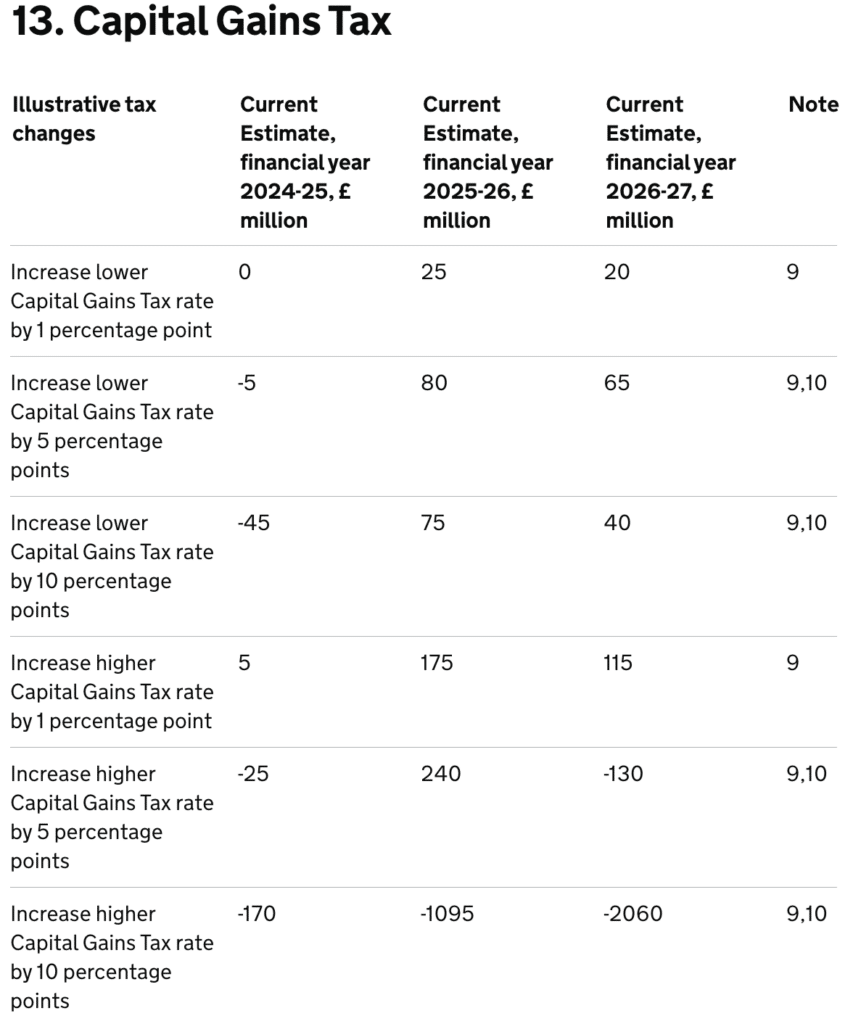

I expect it’s for these reasons that HMRC’s figures on the amounts raised by increasing the CGT rate are very low – indeed their figure for raising the higher 28% rate (homes and carried interest) by 10% is negative:1

The Lib Dem plan is, broadly speaking, to raise the lower rate by 20% and the higher rate by an average of 15%. HMRC’s figures suggests that doesn’t raise the £5.2bn of revenue projected by the Lib Dems

All in all, the consequence of applying HMRC’s figures to the Lib Dem proposals isn’t £5.2bn of revenue – it’s about a £3bn loss in 2026/27. And will be worse than that once you factor in the cost of the new reliefs the Lib Dems are proposing – inflation relief plus an increased annual exempt amount.

So the rather unfortunate result is that if you are a politician who wants to raise revenues by putting up CGT, you shouldn’t tell anyone about it in advance. That’s not great in the context of an election campaign.

The substance of the proposal

What about the substance of the proposal? If we assume for the moment that the Lib Dems could turn back time and undo their announcement, then dramatically enact it in a Budget?

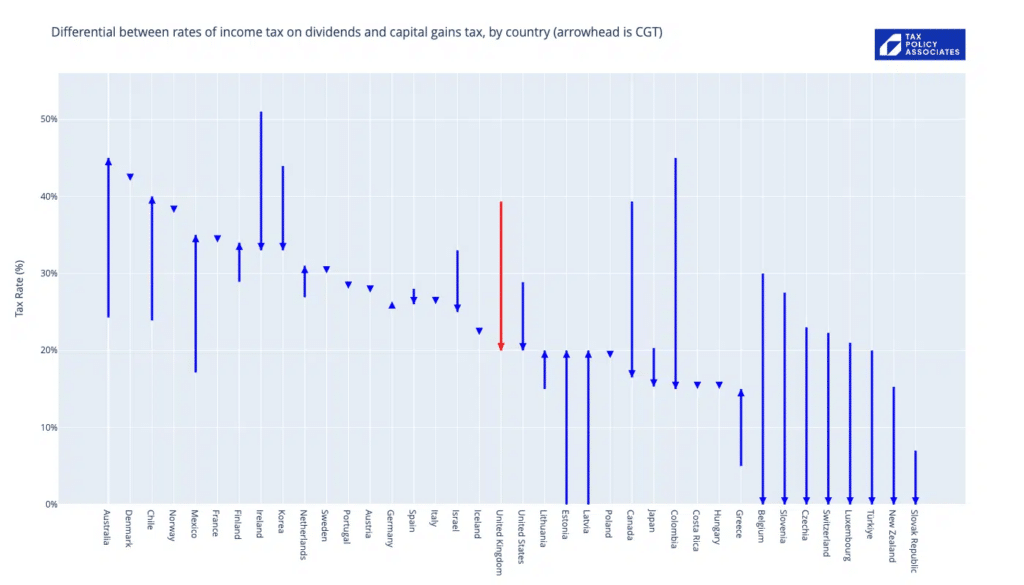

The proposed 40% and 45% rates would be some of the highest in the developed world:

When dividends on shares are taxed at a top marginal rate of 39.35%, taxing capital gains on shares at a higher rate doesn’t make much sense. Owners of e.g. private companies will opt to take their return by dividend. So any revenues from the higher rate would in the main come from real estate.

However if this is combined with a sensible inflation relief then the effective rate (which is what matters) would in many cases be lower.

So, all in all, the substance of the CGT proposal is in many ways sensible (however perhaps too great an increase)., but pre-announcing the measure completely undermines it, and (on HMRC’s figures) generates a loss.

Bank taxes – £4.3bn

The Lib Dems say this:

“Reverse Conservative cuts to bank taxes: Reverse Conservative tax cuts for the big banks, restoring Bank Surcharge and Bank Levy revenues to 2016 levels in real terms.”

This is not an accurate statement. There was no “tax cut”.

The history looks like this:

- In 2015, corporation tax was cut from 28% to 20%.

- An 8% surcharge on banks was introduced for two reasons. First, to stop the banks getting the benefit of the tax cut. Second, to compensate for a reduction in the scope of the bank levy, so it would apply only to banks’ UK balance sheets, and not the worldwide balance sheets of UK banks (which was thought, I think correctly, to make UK banks uncompetitive).

- In 2017, corporation tax was cut to 19%; the surcharge stayed the same.

- From 2023/24, corporation tax went up to 25%. The surcharge was cut from 8% to 3%.

- So banks are paying the same 28% tax on their profits that they were paying prior to 2017, and slightly more than the 27% they paid from 2017 to 2023..

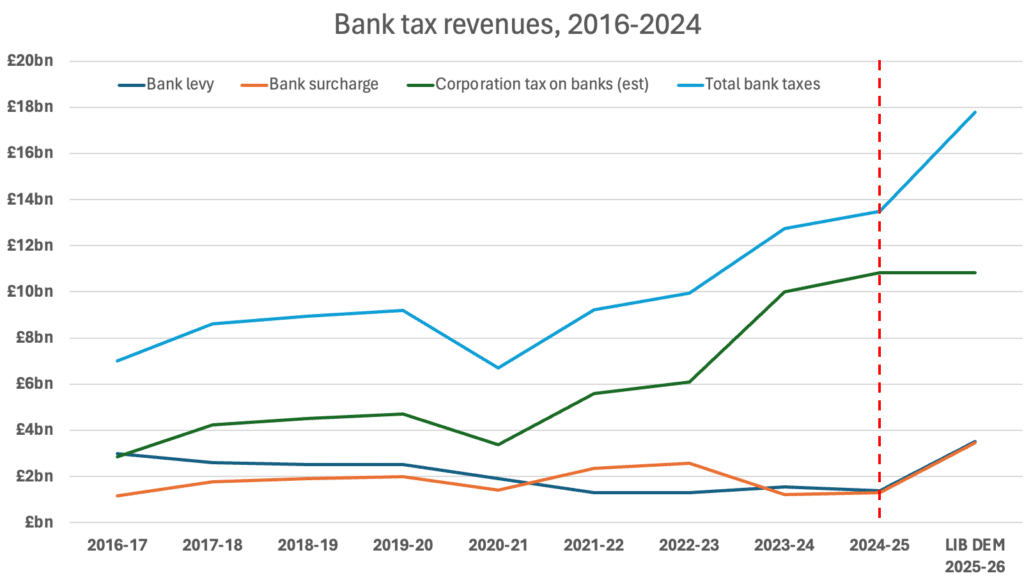

Banks’ overall tax position since 2016 – bank levy, bank surcharge, and corporation tax, looks like this:2

So total tax paid by banks has gone up.

The £4.3bn the Lib Dems are proposing to collect represents about a 30% increase in bank taxation. It would be better to be up-front about that rather than claiming it’s reducing a cut.

Who pays for the tax increase?

Probably the approx £2bn increase to the bank surcharge will be borne by some mixture of bank shareholders and bank employees.

The £2bn increase to the bank levy, on the other hand, is different.

The bank levy is a bad tax that should be abolished (and replaced by increasing the surcharge). Not least because there is good evidence that the cost of the bank levy isn’t actually borne by banks, but by their mortgage customers in the form of higher rates.3

Buyback tax – £1.4bn

The Lib Dems claimed a tax on share buybacks would raise £1.4bn. We believe it will raise much less, and plausibly nothing at all. The Institute for Fiscal Studies agrees.

Cut VAT on electric vehicle charging

The Lib Dems are proposing to cut VAT on electric vehicle charging. No separate figure is given for this – it’s part of their overall £570m transport figure.

It is, however, a bad idea. All the evidence is that the tax cut would not be passed to consumers – it would be retained by suppliers. Even if one wanted to subsidise EV charging suppliers, this is a bad way to do it, because you’re giving existing suppliers a windfall, rather than incentivising the construction of new charging points. We wrote about these issues here, and about the evidence that single-product/service VAT cuts generally don’t cut prices.

Windfall tax on oil and gas profits – £2.1bn

The Lib Dems say:

“A proper windfall tax on oil & gas super-profits: Scrap the ‘investment allowance’ loophole, increase the headline rate and extend it to profits since October 2021 when Liberal Democrats first called for its introduction.”

We have previously criticised the existing windfall tax, and suggested it could raise considerably more. We can’t assess the Lib Dem proposal properly, as there are no details, however comments sent to us by the Lib Dem press office suggest that they are turning the windfall tax into a permanent tax:

“We would expand the Energy Profits Levy by removing the “investment allowance” loophole, increase the headline rate, extend it to profits since October 2021 and extend it beyond March 2028. This would raise extra revenue in every year of the Parliament, with an extra £2.1 billion a year in 2028-29.”

Digital services tax – £2.1bn

The Lib Dems say:

“Raise the Digital Services Tax on tech giants: Increase the Digital Services Tax on social media firms and other tech giants from 2% to 6%.”

There is a lot of history here. Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) were introduced by the UK and others in 2018, applying from 2020. The US was most unhappy, considering it unfair to introduce a new tax which (in the main) only applied to US businesses. There was a threat of retaliatory action from the US, and eventually a compromise. A new multilateral tax on all cross-border businesses (not just digital ones) would be created by the OECD – “Pillar One”. Once it was adopted, DSTs would be abolished. A formal statement to this effect was agreed by the UK, United States, Austria, France, Italy and Spain (and later extended to end June 2024).

The difficulty is that, whilst the OECD global minimum tax (“Pillar Two”) was a success and has been implemented, Pillar One is going nowhere.

It is unclear what’s going to happen. The deal with the US expires at the end of this month, and in theory the UK could then increase its digital services tax rate. But for the UK to unilaterally triple the rate without any discussions is likely to be seen by the US administration as provocative.

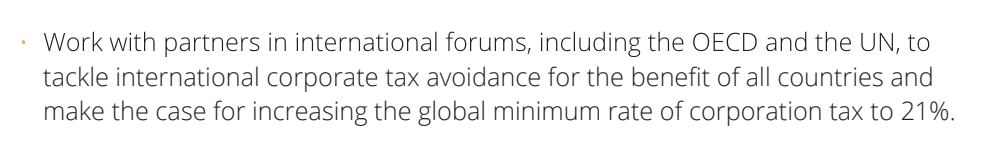

The Lib Dems say elsewhere in their manifesto that they want to:

This (sensible) aim is likely to be undermined by taking unilateral action on DSTs.

Sewage tax on water company profits – £260m

“Sewage tax on water company profits: Apply an additional 16% tax on water company profits.”

There could be an interesting proposal to apply a tax on water companies reflecting the amount of sewage they discharge. This isn’t that – it’s just a tax.

So it won’t change behaviour. It’s also unclear how much it will raise given the well-publicised lack of profitability in the sector.

Tackle avoidance and evasion – £7.2bn

“Tackle tax avoidance and evasion: Narrow the £36 billion annual tax gap by investing an extra £1 billion a year in HMRC to improve customer support and boost compliance and anti-avoidance activities.”

We assessed the potential to raise additional funds from avoidance/compliance here.

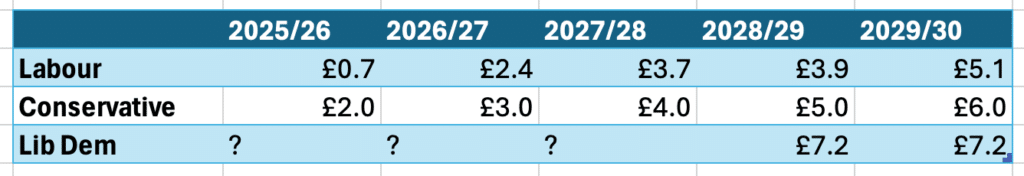

The three main parties have provided three very different sets of claims for how much revenue they could raise:

The Labour Party plan is in their “Plan to Close the Tax Gap” document. The Conservatives’ included a plan as part of their National Service press release. This doesn’t appear to be publicly available; we’re publishing it here. The Conservative figures weren’t in that press release, but are in their manifesto costings document

The Lib Dems just present the £7.2bn figure as 2028/29 funding in their manifesto costings document. They don’t give figures for earlier years. There is no published plan. I asked them about this, and their press office told me:

“We will invest an additional £1 billion a year in HMRC to tackle tax avoidance and evasion – more than Labour or the Conservatives. We are confident that this would enable us to raise an extra £8.23 billion a year by 2028-29 – an achievable and realistic figure. Jim Harra, Managing Director of HMRC, told the Public Accounts Committee that every £1 invested in cracking down on tax avoidance and evasion raises between £9 and £18. That would mean net revenue of £7.23 billion a year in 2028-29.”

So unfortunately the Lib Dems stand out: for having no plan, for claiming the largest revenues, and for assuming the revenues ramp up faster than others.

Reform aviation tax – £3.6bn

“Fairly reform aviation taxes: Reform the taxation of international flights to focus on those who fly the most, while reducing costs for ordinary households who take one or two international return flights per year.”

No further details are available, but this represents a doubling of existing air passenger duty. It’s difficult to combine an environmental aim with protecting “ordinary households” when the majority of flights are taken by ordinary households, for leisure. If the intention is to track the number of flights everybody takes then that would require a centralised individual flight system; the practicalities are outside our expertise, but it would presumably take time to implement.

Private jet flights – £380m

“Super tax on private jet flights: Introduce a new tax on each private jet flight and remove the VAT exemption for private flights.”

No further details are available

Loan charge – £3.2bn?

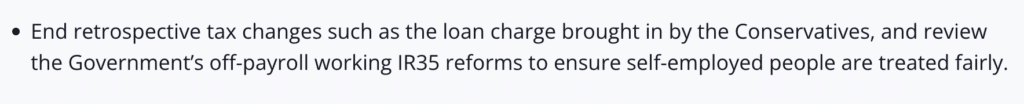

The manifesto says the Lib Dems will end the loan charge:

The loan charge was a controversial anti-avoidance measure that raised about £3.2bn in total. Are the Lib Dems saying they’ll refund that? If they are, why isn’t it in their costings? And if not, what does this proposal mean?

If this is just saying “we won’t do that again” then a large number of loan charge taxpayers are going to feel very let down.

Tax cuts and tax reforms

There are no tax cuts in the manifesto. Nor are there any tax reforms (except, perhaps, the reintroduction of inflation relief for CGT). That is disappointing.

Disclosure: Our founder, Dan Neidle, is a member of the Labour Party, and sits on its most senior disciplinary body. His tax policy analysis is widely regarded as non-partisan, and he was highly critical of Labour Party tax proposals in the 2017 and 2019 elections.

Footnotes

We expect that’s because HMRC anticipate a significant decline in sales; acceleration effects are much less likely given the difficulty of exchanging on a sale within three months. ↩︎

I’ve had to estimate the figure for bank corporation tax by simply multiplying the surcharge by the appropriate ration of CT:surcharge. I then calculate the effect of the Lib Dem changes in 2024-25 by assuming profit is unchanged and we go back to 2016 levels of levy and surcharge. ↩︎

When businesses are taxed on their profits, the burden is borne by some mixture of shareholders and employees (the precise balance depends upon the wider economic environment). However when businesses’ pre-tax costs are increased, for example by a tax like the bank levy, we can get a different result. Banks usually price their interest/lending as the cost of their own funding plus the “spread” – their profit. Anything that increases their costs therefore will potentially increase the interest they charge customers. Business customers can go elsewhere. Consumers can’t. And this is what the EBRD study found: “the tax is shifted to customers with the smallest demand elasticity, such as households”. ↩︎

12 responses to “Our take on the Lib Dem manifesto”

On the air travel point. In what way is APD not the vehicle to achieve the policy aim? (And focus on the flights with the highest clim)ate costs which are not necessarily long-haul? https://ourworldindata.org/travel-carbon-footprint

Why and how would we target frequent flyers? Other Pigouvian taxes just focus on the transaction or activity, so we don’t tax frequent smokers or drinkers or drivers more than less frequent.

I agree – it’s populism, not environmentalism

If I’ve understood correctly, HMRC’s CGT calculations represent the expected tax impact (after behavioural response) of a change in the CGT rate (in isolation).

The Lib Dem proposal is a (significant) change in the CGT rate but with the introduction of an indexation allowance alongside that will materially dilute (in many cases) the change in the effective rate (and therefore the overall behavioural response).

For example, if a gain of 50% is made over a period when cumulative inflation was 20%, a higher rate taxpayer would pay the proposed 40% rate only on 3/5 of the gain, so an effective rate of 24% (same as the current rate).

Of course, mileage will vary depending on the size of the real gains and period over which they are realised (outsized gains over shorter periods taxed at higher effective rates, pedestrian gains over longer periods taxed at lower effective rates).

So I don’t understand using HMRC’s calculations to say that the higher rate will reduce the tax received (based on behavioural response to that alone), and then simply saying that the indexation allowance will further reduce the tax received (without considering the impact of this on the behavioural response).

Agreed of course on the downsides of pre-announcing the CGT changes, that there’s a cost of increasing the annual exemption, and that it’s unlikely the measure raises anything like the Lib Dems project.

But otherwise I’m still inclined to think it’s probably still a fairly sensible proposal from a tax fairness point of view (and probably neatly deals with matters such as carried interest, which doubtless fall into the outsized gains over shorter periods category).

The Lib Dems provide zero detail, but I’m assuming they’d only give indexation relief from the point the law changes, not going back pre-2024. That means that indexation relief is relevant to yield going forward (and surely reduces it!), but won’t change peoples’ incentives to (e.g. for shares) accelerate disposals and crystalise historic gains, or (e.g. for real estate) defer disposals to avoid crystalising historic gains.

Thanks Dan, makes some sense based on that assumption, which is basically that they combine a higher rate with an indexation allowance in the most cack-handed way possible!

Given it’s possible Labour mimic Lib Dem policy and look to increase CGT rates (having refused to rule it out), can you see a way of moving to higher rates (closer to or aligned to income tax, to limit incentives to reclassify between income and gains) with a true indexation allowance (to only tax real gains) that could be (materially) revenue-generative?

This comment on Bank Tax (“every year”) isn’t quite right as the rate was 27% (19% + 8%) for the period during which the CT rate was 19%:

So banks are paying the same 28% tax on their profits that they have every year since 2015.

thank you – now fixed!

Curious that the Lib Dems seem to want to unwind IR35 changes. Anecdotally it seems like that has forced many contractors to start paying income tax and NI like the rest of us in recent years so I assume has increased total tax revenues. Unwinding IR35 would presumably just cut tax revenues, yet has not been costed.

On the frequent flyer tax you are wrong unless you have the concept of ordinary as the wealthiest 10-15% of the population, eg from this article: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-56582094

In the UK, 70% of flights are made by a wealthy 15% of the population, with 57% not flying abroad at all.

While this from The Independent:

Some 90 per cent of domestic flights in the UK were taken by just 2 per cent of English flyers in 2019, new analysis of government data has revealed.

https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/frequent-flyers-domestic-flights-uk-b1954900.html

Resolution Foundation has also found something similar with the wealthiest portion of the population taking most flights. Can’t find the link.

I fear you’ll find the “ordinary households who take one or two international return flights per year” are in the top 15%, or close to it.

Domestic flights are obviously a little different.

It’s also not clear how you’d distinguish between the different types of flyer. Some centralised tracking system?

https://www.libdems.org.uk/fileadmin/groups/2_Federal_Party/Documents/PolicyPapers/Manifesto_2024/For_a_Fair_Deal_-_Liberal_Democrat_Manifesto_2024.pdf

thank you very much!