We’ve been asked a few times to analyse the revenue impact of imposing 20% VAT on private schools. We’ve declined, because it’s a complicated piece of work which probably requires a large team with economic and educational expertise – the actual tax element is relatively small and straightforward.

UPDATE 11 July 2023: this article is now out of date – the IFS has published a serious piece of research on the subject

UPDATE 17 March 2024: the Adam Smith Institute has published a paper. Sadly it uses the 25% figure I discuss below, which looks extremely unreliable.

A think tank, EDSK, published a paper today looking at this point. Unfortunately, they have not actually undertaken their own analysis, just made some simple calculations based upon previously published figures. The problem is that those figures are, in our view are highly questionable, and perhaps useless. Hence this is a case of “garbage in, garbage out”, and we would caution against taking any figures in the report seriously.

For the same reason, we would caution against taking any of the various figures floating around seriously, unless and until a full analysis is undertaken.

Credit to EDSK – their paper readily admits its own flaws, right at the end – key effects were not taken into account. But these are significant issues which can’t just be ignored:

The questionable figures

Any estimate of the revenue impact rests upon a key question: what percentage of children would leave private schools if VAT was imposed? The paper uses two previous estimates: 5% and 25%. It treats them as higher and lower upper bound estimates:

But the 5% and 25% figures shouldn’t be treated so seriously.

The 5% figure comes from the 2019 Labour Party manifesto. It took a price elasticity estimate from an IFS analysis which looked at the impact of changes in school fees on the rate of children going to private schools. Then the Labour Party simply applied the elasticity to a 20% price increase.

This was not a good approach. The IFS paper looks like a serious piece of work, but it looked at much smaller prices than 20%, and occurring over a long period. So it is likely incorrect to assume the IFS elasticity holds for an immediate 20% VAT increase, and this error surely means that the Labour Party figure was understated. On the other hand, the IFS found price sensitivity only at entry points – ages 7, 11, 13, and so it’s not correct to simply apply this elasticity to all private school pupils. That would tend to over-state the effect. Taken together, these effects render the 5% estimate of limited and perhaps no use.

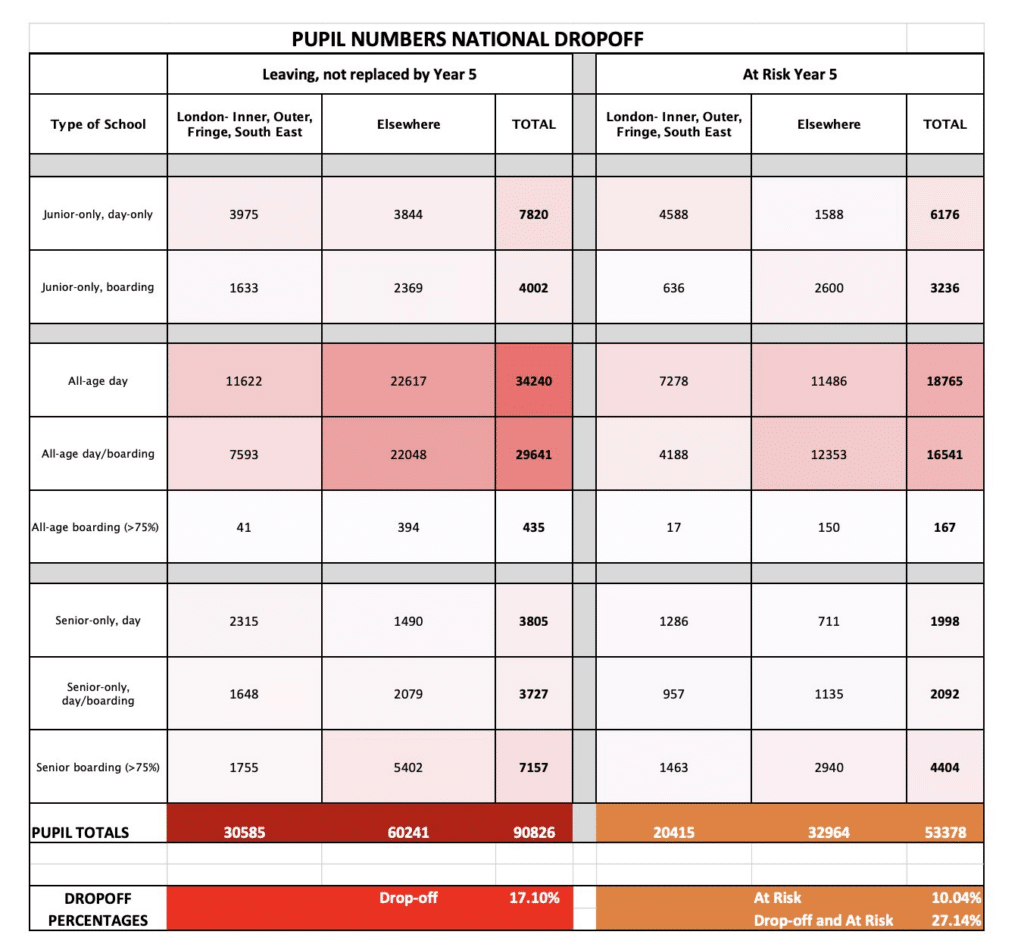

The 25% figure comes from a slightly mysterious survey of heads and parents at 21 schools by a consultancy engaged by the Independent Schools Council. The mystery being that details of the methodology are scant and, even in principle, surveying parents and headteachers in a mere 21 schools seems unlikely to reveal much about what would actually happen across the country if school fees increased. The likelihood of conscious and unconscious bias is obvious:

Exactly how the calculations were carried out is not revealed in the paper, but there is no evidence of any statistical analysis, and results are presented to two decimal points without any discussion of statistical error (or indeed even a single mention of any statistical tools).

Hence we would regard the 25% figure as meaningless. We don’t think EDSK should have taken them as upper/lower bound estimates, or even used them at all.

How would an actual analysis be undertaken?

Having spoken to a variety of economic and education policy experts, we believe a proper analysis would look something like this:

- Dividing independent schools into different size/wealth/location categories. Then for each, analyse sample accounts & model the extent to which private school will absorb additional costs, reducing profit (for for-profit schools), cutting back on capital expenditure, etc.

- Where the VAT leads to increased fees for a category of school, model the effect on different categories of parents – different income levels, overseas vs local etc. Simple uniform elasticity calculations don’t really cut it, because there are so many different types of schools and children/parents. One would also need to model parents switching from more expensive to less expensive private schools. This would all be very challenging, and none of the experts we spoke to were sure how it would be done (albeit these were brief conversations).

- To complicate things further, Some schools may increase bursaries/i.e. cross-subsidise from wealthier parents to poorer. So impact may be greatest on “middle income” parents (relatively speaking). And/or some schools may scrap bursaries, making the impact greatest on lower income parents. Predicting the outcome here may not be straightforward.

- That gives the response for different types of parent in different types of school. But then it’s necessary to adjust for a significant time factor. Expect a small immediate effect (i.e. few parents would pull their children out mid-year). Then a somewhat larger effect for pupils moving into next academic year but, per the IFS paper, by far the greatest impact on new pupils starting at the school at 7, 11, 13. There would plausibly be an initial time-lag to reflect the fact that parents may have missed the deadline to start in the state sector.

- Then model how the schools would respond to the pupils leaving. This would be a sudden shock for the sector, and we could see dramatic reactions. Some schools could become uneconomic after losing just a few pupils, and shut down. Other schools could change their model to enable them to reduce fees. In the longer term, new schools could start up operating a lower-cost model. It’s often said that, in the 1970s, Eton had contingency plans to move to Ireland – that must be another possibility, although query if the schools most able to afford so dramatic a move would economically need to?

- Then find the cost for educating each category of pupil that leaves and joins the state system. The EDSK paper does this by pulling out a calculator and dividing (1) the total cost of state education system by (2) number of pupils:

- That’s not reflective of the actual cost. The extent to which local state schools have capacity to absorb leaving pupils with/without significant additional expenditure will vary hugely area-to-area and school-to-school. One plausible story: the incremental costs of absorbing a few pupils are very small, particularly given long-term demographic trends (fewer young people). Another plausible story: private schools thrive in areas with less choice of state school, and those schools are already packed, so there simply isn’t space to absorb the influx of new pupils, and new buildings/capital expenditure would be required. Then the costs would be large. Which is it? Or is it something else? Without actually undertaking a detailed analysis of private schools, state schools and demographics, this is just more guesswork.

- Then, in case the above is insufficiently challenging, there are the wider third and fourth order effects:

- What do people who leave the private sector do with the saved £? Spend it on tutors? on holidays? Save it? Reduce debt? Perhaps this enhances the tax yield, because parents now buy more VATable stuff. Or perhaps not?

- What happens to teachers who leave private schools? How long are they economically inactive? How much does that take out of the economy and income tax revenues?

So the figures in this paper are just guesses multiplied by guesses. The difficult and uncertain analysis that is omitted is where the truth actually lies. To be fair, the paper really admits that at the end.

How much would the 20% VAT be offset by recovering VATable expenses?

Something the report gets right is that the cost for a private school of imposing 20% VAT would not be 20%.

At present, private schools suffer VAT on their expenses (“input VAT”) but, unlike a normal VATable business, they recover little or none of this.

In other words, a normal business buys a £1,000 computer. They pay £1,000 plus £200 VAT, but can recover the VAT. Net cost: £1,000. But for a private school, the net cost would be £1,200 (or almost £1,200).

Once school fees become VATable then the private school would be treated in the same way as a normal business. That computer would cost £1,000 net.

The extent of this effect depends on the proportion of a school’s costs that are currently VATable. The majority of the costs will be staff wages, and there’s no VAT on that. The Independent Schools Association estimated the net impact would be 15% – we haven’t seen underlying data supporting this, and so the figure should be used with caution. But it feels in the right ballpark.

What about the technical VAT concerns raised in the paper?

Here we are able to comment fairly definitively. The concerns raised are weak and in some cases incorrect.

This section suggests that there is doubt as to how “closely related” supplies such as boarding accommodation will be taxed.

But that’s straightforwardly wrong. If education becomes VATable then closely related supplies will too. No further legislation would be required.

Then the report suggests there are obvious ways schools could escape the tax:

Trying to avoid the VAT by pushing boarding into a charity would be (naive) VAT avoidance, with no realistic prospect of success.

The paper mentions other potential complications, like the capital goods scheme and people paying years of fees up-front. But these are obvious points that I’d expect any legislation to deal with.

Our conclusion

Technically it is straightforward to impose VAT on private schools. Things only get difficult if it’s done in such a way as to create arbitrary boundaries. For example, imposing VAT on schools charging (say) £8k/year or more would create a powerful incentive for a school currently charging (e.g.) £10k to reduce its fees to £7,999 and then pile on a series of individual charges for books, trips, etc.

Fortunately, politicians never create VAT rules with arbitrary boundaries, so there is nothing to worry about here.

However at present we simply do not know what the revenue impact would be. We don’t know how schools would respond, and the extent to which the tax would be passed-on. We don’t know how parents would respond, and the extent to which pupils would leave the private sector. We don’t know how the State sector would absorb those pupils who would leave the private sector.

We’d therefore suggest disregarding the figures in the EDSK report, and the other figures sometimes referred to. At least until someone actually does the difficult job of undertaking a proper analysis.

More generally, when there’s limited or bad data, the temptation is to use it anyway, because it’s “all we have”. That temptation should be resisted. Garbage in, garbage out.

Leave a Reply