The Scottish Budget was on 13 January 2026.

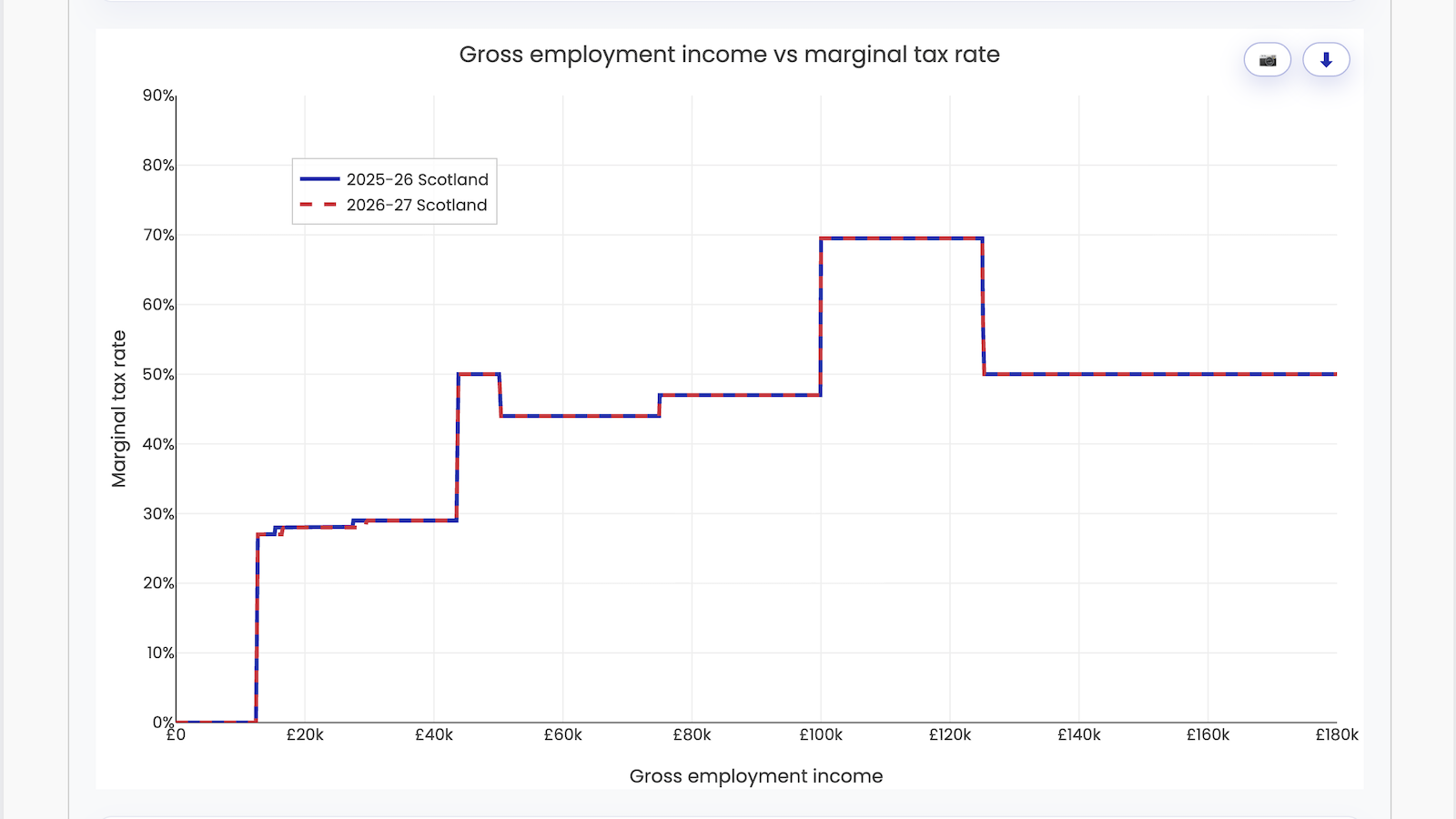

The flagship policy is being widely reported as a cut in income tax1 for low earners, by increasing thresholds from 2026/27. The 20% basic rate will now start at £16,538 instead of £15,398. The 21% intermediate rate will now start at £29,527 instead of £27,492.

This is a very peculiar tax cut. I have four quick thoughts, and an interactive tax calculator showing the effects:

A very small tax cut

The impact looks like this:

- A taxpayer earning £15,398 or more receives a small tax cut – £6.02 at £16,000, rising to £11.40 at £16,538 (i.e. because that’s 1% of the difference between £16,538 and £15,398).

- A taxpayer earning £27,492 or more receives an additional tax cut – £5.08 at £28,000, rising to £20.35 at £29,527 (1% of the difference between £29,527 and £27,492).

- Everyone earning more than £29,527 gets the full benefit of both cuts, i.e. £31.75.

This may be a contender for the smallest income tax cut in history. The previous record holder was the Australian $4 per week tax cut of 2003, widely mocked as a “milk and sandwich” tax cut. The £212 “marriage allowance” introduced by the Cameron Government runs it a close second. The £31.75 cut beats both handily – it’s 61p per week. The amounts are so small that for some small businesses, the time/cost of recoding people’s taxes will be more than the tax they will save.

It’s not a tax cut

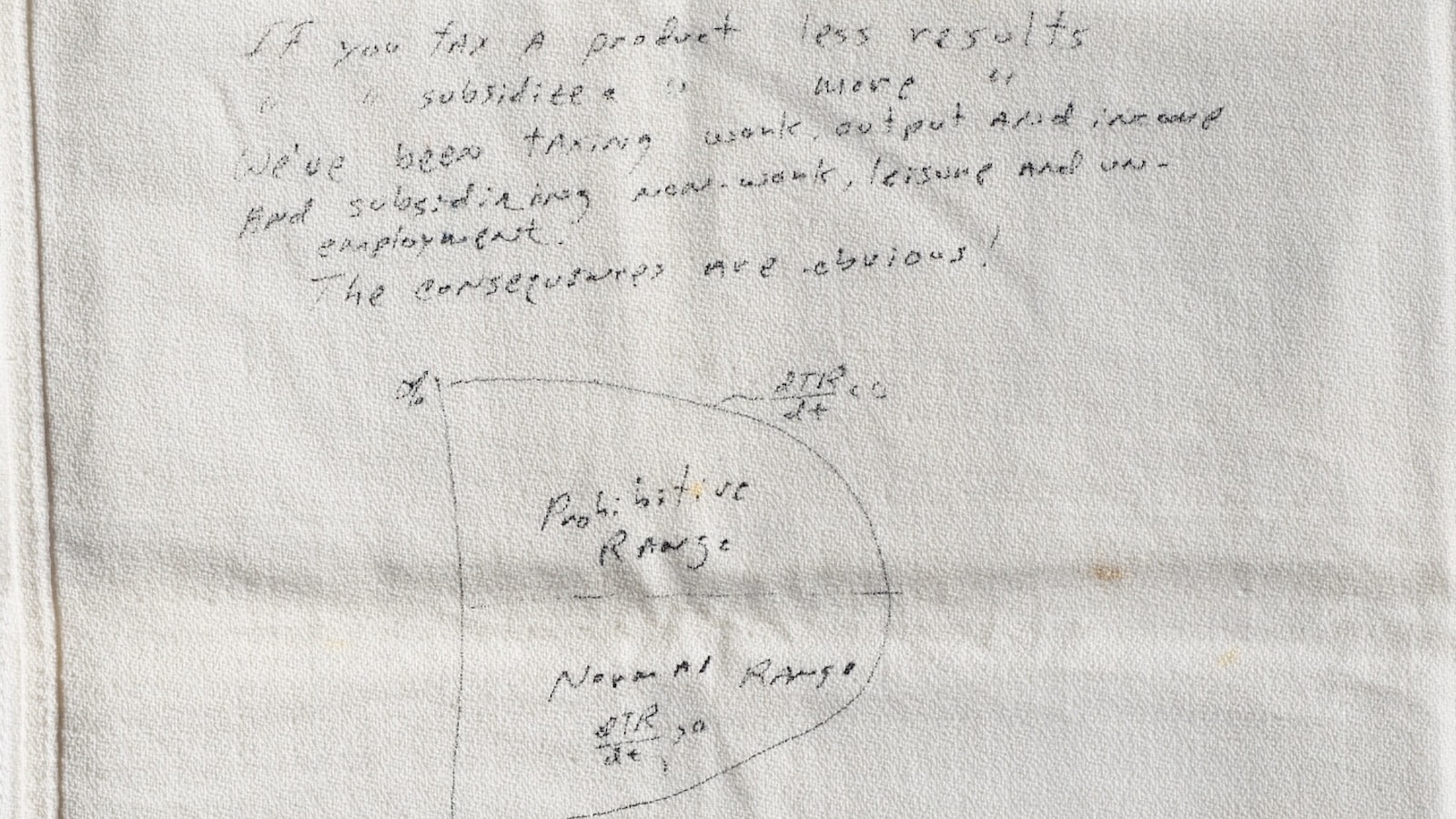

The benefit of the tax cut is undone by “fiscal creep” – the freezing of personal allowances and tax thresholds at a time of relatively high inflation (just over 3%). That pushes the low paid over the personal allowance, and others into higher tax brackets.2

This is a much bigger effect than the “tax cut”. If we just look at the personal allowance, to keep up with 3% inflation, the threshold should have risen from £12,570 to £12,947. It didn’t rise at all – and means that, in real terms, everyone earning £12,947+ is worse off by £72. The “tax cut” means there’s no fiscal creep in 2026/27 for the basic rate and intermediate rate band threshold, but there is for the other band thresholds.3

So in real terms nobody is receiving a tax cut. The real effect of the Scottish Budget is that the income tax increase from fiscal creep is slightly reduced.

Across the whole UK, fiscal creep amounts to a tax increase of £30bn/year. The cost of the Scottish tax cuts is £50m – it’s an irrelevance in fiscal terms.

The benefit goes to higher earners

This is being positioned as a “tax for low earners”, but most of the benefit goes to higher earners. Of the £50m overall cost of the tax cut, about two-thirds will go to the highest earning 50% of taxpayers. That’s because all of the top 50% receive the full £31.75 benefit, but many lower paid taxpayers receive nothing or only £11.40.4 We shouldn’t overstate this, because the amounts involved are so very small. But given the tax cut is symbolic, it’s fair to ask why the symbolism is so odd.

It’s – obviously – all about politics

Given these oddities, why bother to implement a tax cut at all?

The Scottish Government’s Tax Advisory Group (of which I am a member) had no involvement in the decision-making process. This was an entirely political measure.

It’s likely the purpose is to enable the Scottish Government to say that everyone earning the Scottish median income of £31,136 (or less) will pay less tax in Scotland than in the rest of the UK. That had always been their aim, but inflation/wage rises meant it ceased to be true in 2023/24 and probably 2024/25. So the very slight nudge to thresholds is intended to ensure that (at current projected median earnings) the median earner in Scotland pays about £24 less tax than someone on the same earnings elsewhere in the UK (and someone earning less than £29,527 about £40 less). This is, however, very dependent on median earnings. Higher than expected inflation/wage increases will reverse it, as happened in 2023/24.

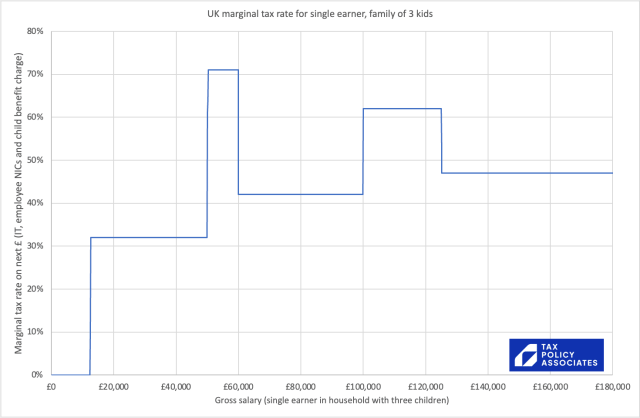

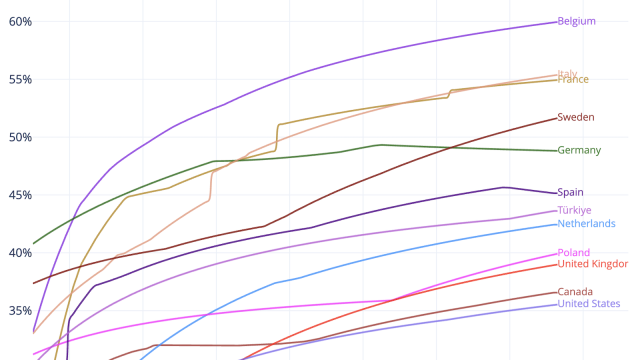

The real difference is for higher incomes. Someone earning £50k pays £1.5k more tax; someone earning £100k pays £3,300 more. That means, overall, Scotland raises about £1bn of additional tax which (broadly speaking) funds additional social and education expenditure. That’s a perfectly valid political choice and, it seems, a popular one. But I’d prefer it was presented more frankly, without gimmicks like “tax cuts” that aren’t tax cuts at all.

The tax calculator

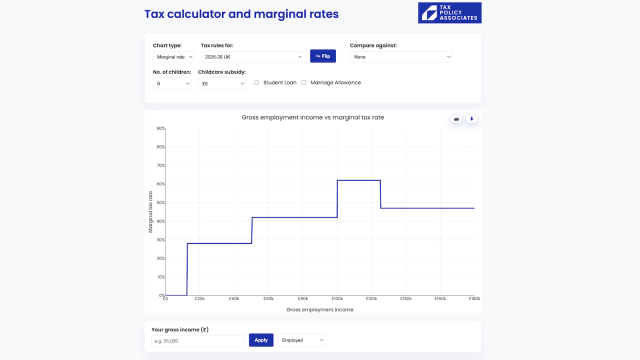

Our interactive tax calculator starts by showing the comparison between Scotland and the rest of the UK. You can also opt to see the change caused by the Scottish Budget, but it’s almost invisible on the chart.

You can view the calculator full screen here.

There’s a guide to how to use it in our Budget analysis here, which also discusses marginal tax rates: what they are, and why the UK marginal rates are so unfortunate.

Code

The code for the calculator is available here. If you want to experiment with different rates, you can download all the files and run “index.html” locally. You can then edit “UK_marginal_tax_datasets.json” and add different scenarios.

Footnotes

Note that this is for income tax on wages; income tax on savings/dividends remains at the UK rates and thresholds; a somewhat irrational quirk of devolution. ↩︎

Scotland has no power to change the personal allowance per se, but it could effectively increase the personal allowance by creating a small 0% rate (with additional changes at the top end to roughly mimic the £100k personal allowance clawback). This would broadly amount to the same thing in economic terms. ↩︎

Note that the IFS presents figures for the value of the tax cut in real terms; ours are in cash terms. ↩︎

A simple back-of-the-envelope calculation: HMRC data shows that, in 2022/23, 9% of Scottish taxpayers paid the starter rate. They save nothing from the tax cut. 38% paid the basic rate – most will save £11.40. Then 35% paid the intermediate rate – most will save £32. 18% paid the higher/top rate – all of them will save £31.75. So the weighted saving of the bottom 47% is c£9; the weighted saving of the top 53% is c£32. So about 78% of the benefit would be going to the top 53%, if earnings were the same as in 2022/23. Wages have of course risen significantly since then, pushing many taxpayers in the bottom 50% into higher bands – that’s bad news for them overall, but means they receive proportionately more of the benefit of the tax cut. Overall we estimate that around 60-65% of the benefit will end up going to the top 50%. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to John C Cancel reply