Most of the attention during and after the Budget will be on the big tax-raising measures. But there are an unusual number of important other items, which appear technical, but will impact everyone from billionaire non-doms to the poorest people in the country. None of these items are likely to be mentioned in the Budget speech, but will be buried somewhere in the mountains of paper that accompanies it.

We’ll be watching for these six:

1. Keeping more non-doms

This could be the Budget measure with the greatest long-term impact.

Jeremy Hunt made the decision to move from domicile to a modern residence-based regime (something we and many others had suggested). Labour took that, and made the additional and politically irresistible promise to close the “trust loophole“.

But there’s a problem. The original Hunt changes ignored a key point: that inheritance tax shapes decision-making by non-doms (and indeed many others) far more than taxes on income and capital gains. Hunt’s reforms had inheritance tax applying in full, at the normal 40% rate, once a non-dom had been resident in the UK for ten years. For many non-doms, paying a bit more UK tax on their dividends and capital gains is not a big deal. But the prospect they could fall under a bus, and then their children would lose 40% of their worldwide assets in UK tax, is a very big deal indeed.

That wasn’t a terribly big point back when Hunt made his proposal, because the – very deliberate – “loophole” meant that the seriously wealthy would keep their non-UK assets in trusts and so avoid inheritance tax.

By abolishing the loophole, Labour made the “bus” problem something that couldn’t be avoided. The OBR estimated that 25% of the wealthier non-doms – those with trusts – would leave the UK. This is why.

Fortunately it’s not too late. Despite some media reports, informed observers generally believe no more than 5-10% of non-doms have left so far.

There’s a great summary of the changes from law firm Macfarlanes⚠️.

Points to watch: Will the Budget revisit any of the detail of the non-dom reforms? In particular, will there be a new, gentler, application of inheritance tax, for example gradually applying in stages from year ten to year twenty, rather than applying immediately in year ten?

2. Solving the small company tax gap mystery

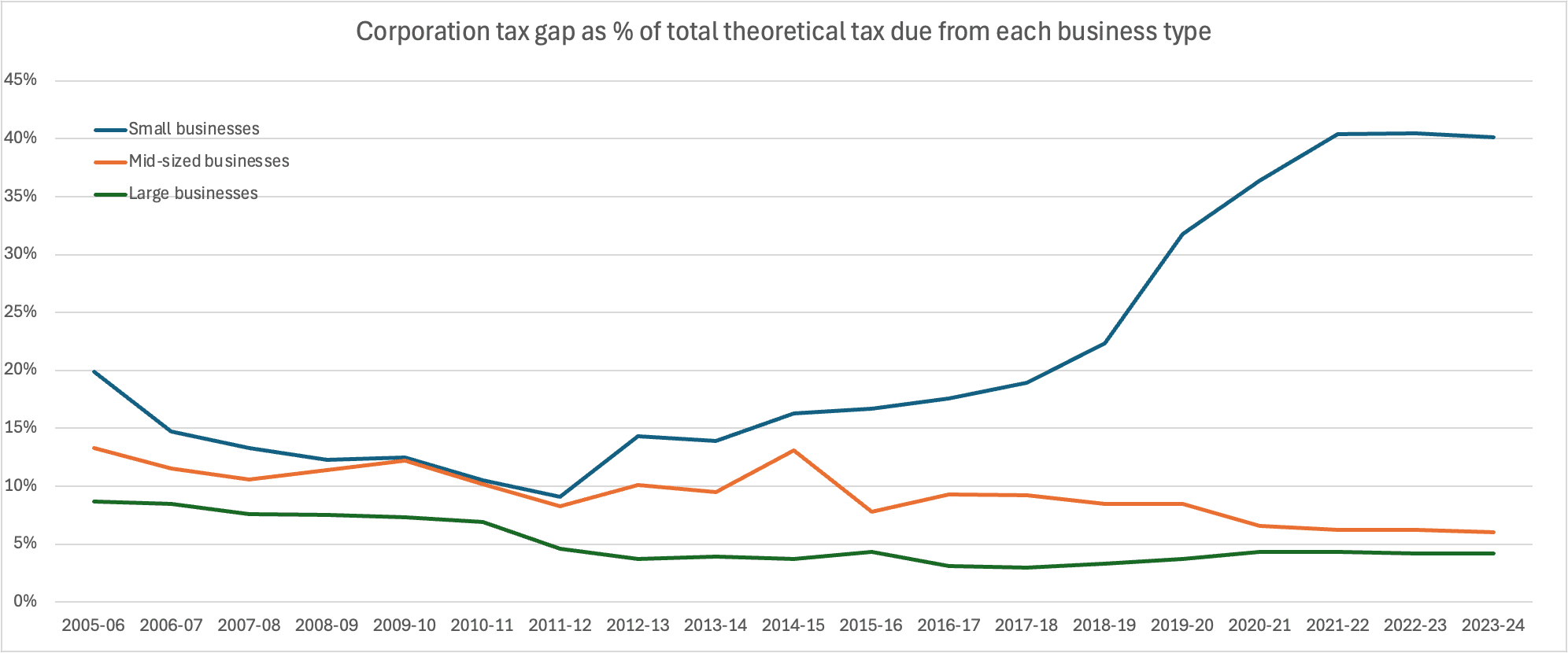

40% of all corporation tax due from small businesses is now not being paid:1

That sharp uptick in 2019/20 may have initially been caused by the pandemic, but we don’t see that effect for other types of taxpayer, and it’s now clear that the trend didn’t slow down after the pandemic.2 Part of the changes appears to be due to a change in methodology, but most is not.3

There’s a sharp contrast with the large and mid-sized business corporation tax gap, which HMRC have been remarkably successful at closing.

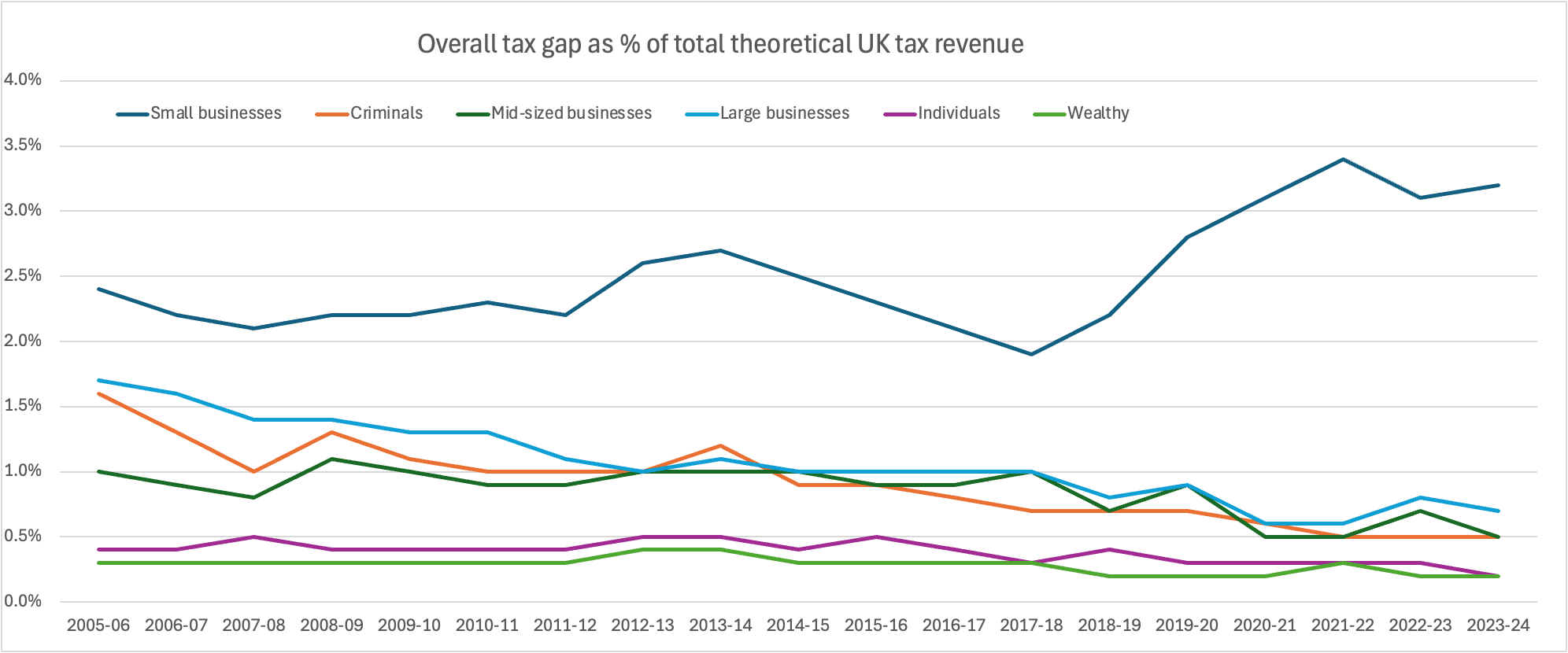

The trend isn’t confined to corporation tax – the overall small business tax gap has also ballooned:4

These effects mean the small business tax gap is now at least £10bn/year higher than it should be.5 The surprising thing is that nobody seems to know why this is – not the team who work on the tax gap calculations, and not HMRC or HMT policy experts. There are several theories – in our view the most plausible is that the trend is driven by avoidance, evasion and non-payment which is technically classified as “small business”, but is really just individuals using companies to avoid/evade tax.

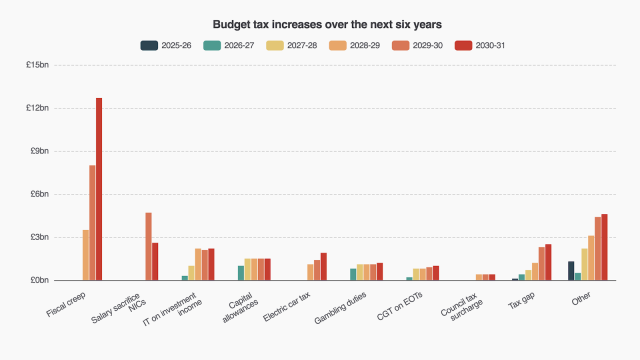

Points to watch: will there be recognition that this is an issue, and an announcement that Government will task HMRC with identifying whether the £10bn represents a real loss and, if so, what should be done to collect it?

3. Promoters of tax avoidance

Many of our investigations have concerned what are often called “tax avoidance schemes”, but which are in reality often little more than scams. The schemes usually have no real technical basis, the promoters usually have no tax expertise, and either HMRC loses out or the clients/victims are frequently left with large tax liabilities (or, quite often, both).

HMRC’s official “tax gap” figures show tax avoidance costing HMRC £700m in lost revenue. I and many other observers (within and outside HMRC) believe this understates the problem, because much “avoidance” isn’t properly avoidance at all, and ends up classified by HMRC as evasion or non-payment. Some of the “missing” £10bn of small business tax is likely caused by these schemes.

The Government published a series of detailed proposals in a consultation back in July – “closing in on promoters of marketed tax avoidance”, creating a range of new civil and criminal powers for HMRC. Most importantly, HMRC will be able to charge large penalties to promoters who fail to disclose tax avoidance schemes to HMRC, and Treasury Ministers will be able to make regulations which, once approved by Parliament, will create a “Universal Stop Notice” making promoting a specified scheme a criminal offence.

The package has been highly controversial in the tax advisory world, with many advisers expressing concerns that innocent (which is to say, non-fraudulent) advisers could end up liable. I am sympathetic to some of these concerns, but others I think are overdone. I hope we’ll see finalised proposals which strike the right balance.

Points to watch: will the key “Universal Stop Notice” and penalty measures be included? Will there be new protections for bona fide advisers?

4. Umbrella companies

Millions of people in the UK work are employed by employment agencies for temporary work. That includes NHS nurses, IT contractors, and often low-paid staff such as warehouse workers. But modern practice is that the biggest employment agencies don’t actually employ anyone. They act as middle-men between end-users (like the NHS or Tesco) and “umbrella companies”, which actually hire the workers. When an end-user asks the employment agency to provide a worker, the employment agency then goes out to umbrella companies and asks them to bid to supply the worker (in a process that is, inevitably, now entirely automated).

This creates a dangerous incentive. In a country with a minimum wage, umbrella companies should have little ability to compete on price (other than bidding down their own profits). But if they can find a way to reduce the PAYE income tax, national insurance and employer national insurance on their workers’ remuneration, they can bid less, and win the contract.

We have therefore seen a huge number of schemes run by umbrella companies to not pay the tax that is usually due. Our team hasn’t seen a single such scheme which has any legal merit. Some have involved simple fraud – just stealing the PAYE instead of giving it to HMRC. More usually the schemes are dressed up as tax avoidance schemes, with the worker supposedly paid in some bizarre manner (such as via an option over an annuity) that avoids tax. In our view these “avoidance” schemes are in reality also fraud, because the legal positions taken are unsupportable. And in almost all cases when HMRC challenges an umbrella company, it’s abandoned by the shadowy figures running the scheme, goes into administration and the tax is never paid.

The scale of the schemes can be seen by looking at HMRC’s list of named avoidance schemes – almost all are umbrella/remuneration schemes. We’ve spoken to informed sources within the agency/remuneration world who believe that several billion pounds of tax is being lost every year.

Draft rules were published in July which make employment agencies jointly liable for tax defaults by umbrella companies. The idea is a sound one: create an incentive for agencies to police the umbrella companies they work with. The problem is that the proposals create another incentive for bad actors: instead of just controlling umbrella companies, acquire/create recruitment agencies. Then, when HMRC attacks schemes, the recruitment agency will be abandoned, leaving HMRC with no way to collect the tax.

The answer is a draconian one: put responsibility on the end-user – the company actually hiring the worker. Tesco or the NHS in our example above. I’d then expect end-users to put very robust measures in place to ensure the tax is paid (for example paying the tax amount into an escrow account so the agency/umbrella can’t touch it).

Points to watch: Will the measures go ahead? And if they do, will liability be limited to agencies and not the end-users? If the measures are enacted without end-user liability then I expect in practice they will have only a limited effect.

5. HMRC penalties: the impact on the poor

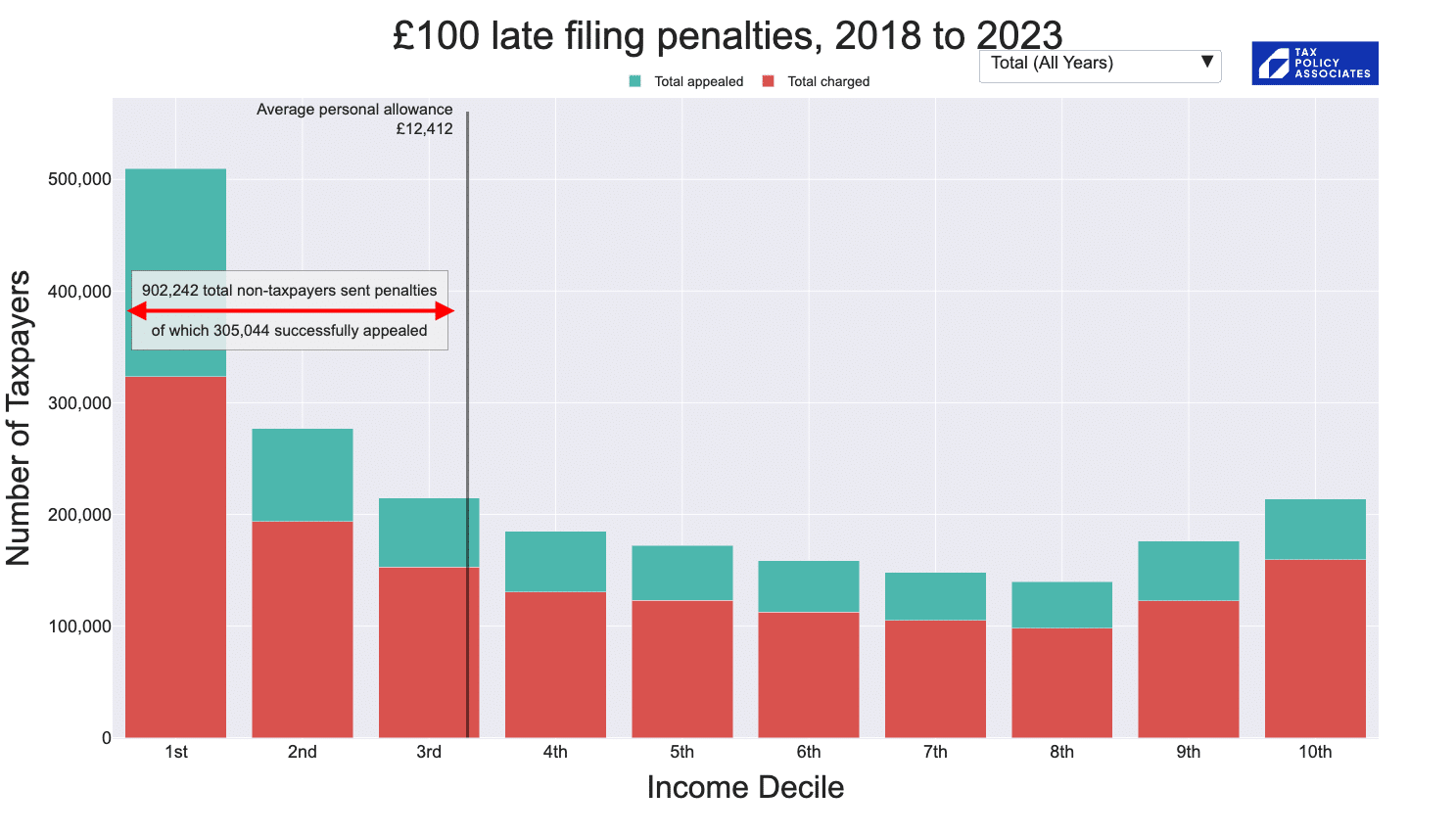

Over the past five years, HMRC have issued around 600,000 late-filing penalties to people whose incomes are too low to owe any income tax at all.6 Far more penalties were issued to people too poor to pay tax than to those in the top income deciles:

This is not a niche edge-case: it is baked into the design of the current regime. Since a 2011 reform, late filing penalties are no longer capped by the tax actually due – so a person who ultimately turns out to owe nothing still keeps the penalties.7 Many low-income taxpayers are brought into self assessment by HMRC error, historic earnings, or very small amounts of self-employment income – over £1,000 a year is enough to trigger the filing requirement8

Things should, in principle, improve – the current penalty rules are being replaced with a new “points-based” penalty regime under which nobody is fined for a first missed deadline and total late-filing penalties are capped at £200.9 But the penalty reforms are part of the Making Tax Digital project, requiring businesses and the self-employed to keep digital records and submit tax information to HMRC electronically. That means the changes will only apply to those with incomes over £50,000 from April 2026, over £30,000 from April 2027, and over £20,000 from April 2028 – and there is currently no timetable at all for anyone below that.10 The Low Incomes Tax Reform Group has described the result as a “two-tier system” in which those on the lowest incomes are left with the old, harsher rules.

This means that, for the foreseeable future, a millionaire landlord filing his tax return late won’t pay a penalty; but his low-income tenant will continue to pay up to £1,600. That’s indefensible, and something no Labour Chancellor should stand for.

Points to watch: Fixing this, and stopping charging penalties to the poorest in our society, would only cost £6m. There are few tax reforms that are this good value for money. Will we see any change?

6. Loan charge review

The 2000s and early 2010s saw widespread marketing of tax avoidance schemes which disguised pay/remuneration as “loans”. The idea was that, instead of being paid in the usual way (and paying tax) you received loans from an offshore trust (and paid no tax). I put the word “loans” in quotes because they weren’t really loans at all – in most cases there was never any intention to repay them.

HMRC failed to effectively challenge the schemes, and by 2019 there were over 50,000 people using them, and lost tax running to billions each year. There was no way to launch 50,000 separate enquiries, and so in 2016 the Government enacted the “loan charge” – a one-off charge on scheme users which retrospectively undid the benefit of the schemes. We discussed more of the background here.

This has caused considerable hardship. The promoters selling the schemes cared only about their fees, and never told their clients about the risks they were running. So the taxpayers generally spent the tax they were saving. Worse, a high percentage of the tax saving went in fees to the promoters – so recovering the full tax amount now means that taxpayers are being asked to repay amounts that never went into their pocket.

The loan charge has become mired in controversy, with lobbyists often denying that the schemes were avoidance, and seeking for affected taxpayers to escape without ever repaying the tax they avoided. That’s not justifiable.

The new independent review was announced at Autumn Budget 2024 and formally commissioned in January 2025, led by Ray McCann – a widely respected retired senior HMRC official who went on to work in private practice and was President of the Chartered Institute of Taxation.

The outcome of the review will be published with the Budget papers.

Points to watch: a sensible outcome would be to distinguish between the actual cash tax savings made by the scheme users, and the large fees they paid to promoters. The loan charge should only recover the former. Any excess already paid by taxpayers should be refunded. It would also be good to see new measures against promoters, for example giving the scheme users a right to recover their losses.

Photo by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash

Footnotes

The source is the HMRC tax gap tables – see tables 5.2, 5.4 and 5.5. ↩︎

The only other taxes where the tax gap has gone up over this period are inheritance tax (which likely results from so many more estates becoming subject to the tax) and landfill tax (we don’t know why that is; it’s an area where our team has no knowledge or expertise) ↩︎

There have been a series of upward statistical revisions to data for recent years. These took the 2022/23 small business corporation tax gap from 32% to 40% (with the 2021/22, 2022/23 and 2023/24 figures being essentially identical). However HMRC sources have confirmed to us that these revisions don’t call earlier figures into question, and so the apparent trend in the data is real, and not just a statistical artefact. ↩︎

This is from table 1.4 of the HMRC tax gap tables. HMRC have generally done an excellent job shrinking the tax gap, with declines across the board. But after 2017/18 something changed. ↩︎

The small business tax gap increased from 2.4% of all UK tax revenues in 2005/6 to 3.2% in 2023/24. The rest of the tax gap fell precipitously over that period – large businesses from 1.7% to 0.7%; mid-sized businesses from 1.0% to 0.5%. ↩︎

See HMRC’s FOI response. An interactive breakdown of the data, and the code used to analyse it, is available here. The underlying calculations are on our GitHub. ↩︎

The modern regime is contained in Schedule 55 to the Finance Act 2009, brought fully into effect for self assessment from 2011/12. Under the previous system, broadly, a late filing penalty could be capped by the tax shown as due on the return (for example under s93 Taxes Management Act 1970), so someone with no liability would not normally end up with substantial penalties once they filed. The Low Incomes Tax Reform Group (LITRG) warned at consultation stage that removing the linkage to tax due would risk “wholly disproportionate penalties” for those with low or no incomes: see their response to HMRC’s 2008 penalties consultation, especially para 4.4.1, reproduced at page 5 of LITRG’s later paper, “Self assessment – a position paper”. ↩︎

See the gov.uk guidance on who must file a tax return. In practice, people can also be kept in self assessment long after their circumstances change unless they (or an adviser) tell HMRC they should be removed: see LITRG guidance and HMRC pages on leaving self assessment. Once HMRC’s computer has issued the notice to file, the penalties roll out automatically if nothing is sent back. ↩︎

The new late submission regime is described in HMRC’s guidance note “Penalties for late submission”. In outline, taxpayers accrue “points” for missed filing obligations; once a threshold is reached, a £200 penalty is charged, but there is no further escalation into the thousands. Points expire after a sustained period of compliance. The rules are legislated mainly through amendments to Schedule 55 FA 2009, alongside the wider Making Tax Digital (MTD) programme. ↩︎

See the government’s technical note on the phased implementation of MTD for income tax, and the announcement of revised timings. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Edward Bainton Cancel reply