Doctors, lawyers, accountants, fund managers, and other high earning professionals are often members of partnerships and LLPs. They’re not employees – and so there’s no 15% employer national insurance. This creates a big tax saving. The Times is reporting that Rachel Reeves is considering changing this – and that it could raise £2bn.1

UPDATE evening of 22 October: The Times is now reporting that, to avoid hitting GPs, the change would be limited to LLPs and would not affect general partnerships. That would be a serious error which would create unfairness and economic distortion, and open up avoidance opportunities.

Taxing people differently just because of their choice of legal vehicle is irrational – and there’s certainly a principled justification for equalising the position.2 It also achieves the political aim of mostly affecting only high earners – around 0.1 % of taxpayers receive 46% of all partnership income, and 98% of the tax raised would come from the highest earning 10% of taxpayers.3

But it’s not without political cost – more reasonably paid professionals (like GPs) would also be affected: the average GP who’s a member of a partnership earns £118k, and would see their take-home pay fall by about £6k (although some of the tax revenues raised by the new measure could be used to fund an increase in GP pay).

The response of those affected, and the impact on tax revenues and the wider economy, is hard to predict. There are also practical problems, and fairness issues around where precisely the line would be drawn.

This is certainly something any Chancellor should consider – and there may be ways of squaring the circle, and raising revenue without hitting GPs or creating a series of unfair new anomalies.

The think tank/academic group CenTax published a detailed report in September analysing HMRC data around LLP/partnership taxation. The £2bn figure comes from their report – which I highly recommend. Note that their data is from 2020 – so realistically all the figures should be uprated by around 15-20% for inflation/wage growth.

The figures

This calculator shows how much additional tax would be paid by a partner if the most straightforward version of the proposal were adopted. It also shows how much of that additional tax would be saved if the partnership incorporated. The calculations are local to your PC/phone, and nothing you type is sent over the internet.

There are worked examples in this spreadsheet.

This is all very much a quick approximation, and it doesn’t take the many complicating factors into account.4 Please don’t rely on it for anything more than an illustration of the impact of the proposal.

The current situation – the doctors

When someone is employed, their employer applies employer national insurance to their pay packet. So, for example, if a hospital has £118k to pay its doctors,5 about £16k comes out immediately as employer national insurance. The doctor only ever sees the remaining £100k – and of course pays income tax and employee national insurance on it. He takes home about £70k.

The doctor never sees that missing £16k, and might be completely unaware of it – but in the long term, evidence shows that he’s paying it (because it reduces his wage).

Now imagine a doctor who’s a “locum”. They’re often (but not always) taxed as self-employed. There’s no employer’s national insurance. So the doctor is paid the whole £118k. She’s paying more income tax and national insurance (because of the higher gross pay), but ends up taking home around £76k. Our locum is £6k better off than an employed doctor.6

Let’s take a third category – a GP. The £118k figure I’ve been using comes from the CenTax report – they estimate it’s the average earnings of a GP who’s a member of a partnership.

Most GP practices are set up as partnerships. A traditional partnership is just people working together in business, but many GPs use a more modern entity, a “limited liability partnership” which behaves like a company in most respects but is taxed like a partnership.

A member of a partnership isn’t an employee and (usually) is taxed in the same way as someone who’s self employed. So a GP will be taxed in the same way as the locum. No employer, and overall she’s £6k better off than an employed doctor.

This is a very irrational result.

It looks more irrational when we get to very highly paid professionals.

Highly paid partners

Most of the £2bn revenue comes from people earning far higher amounts than the £118k received by the average GP. Around 0.1 % of taxpayers receive 46% of all partnership income.

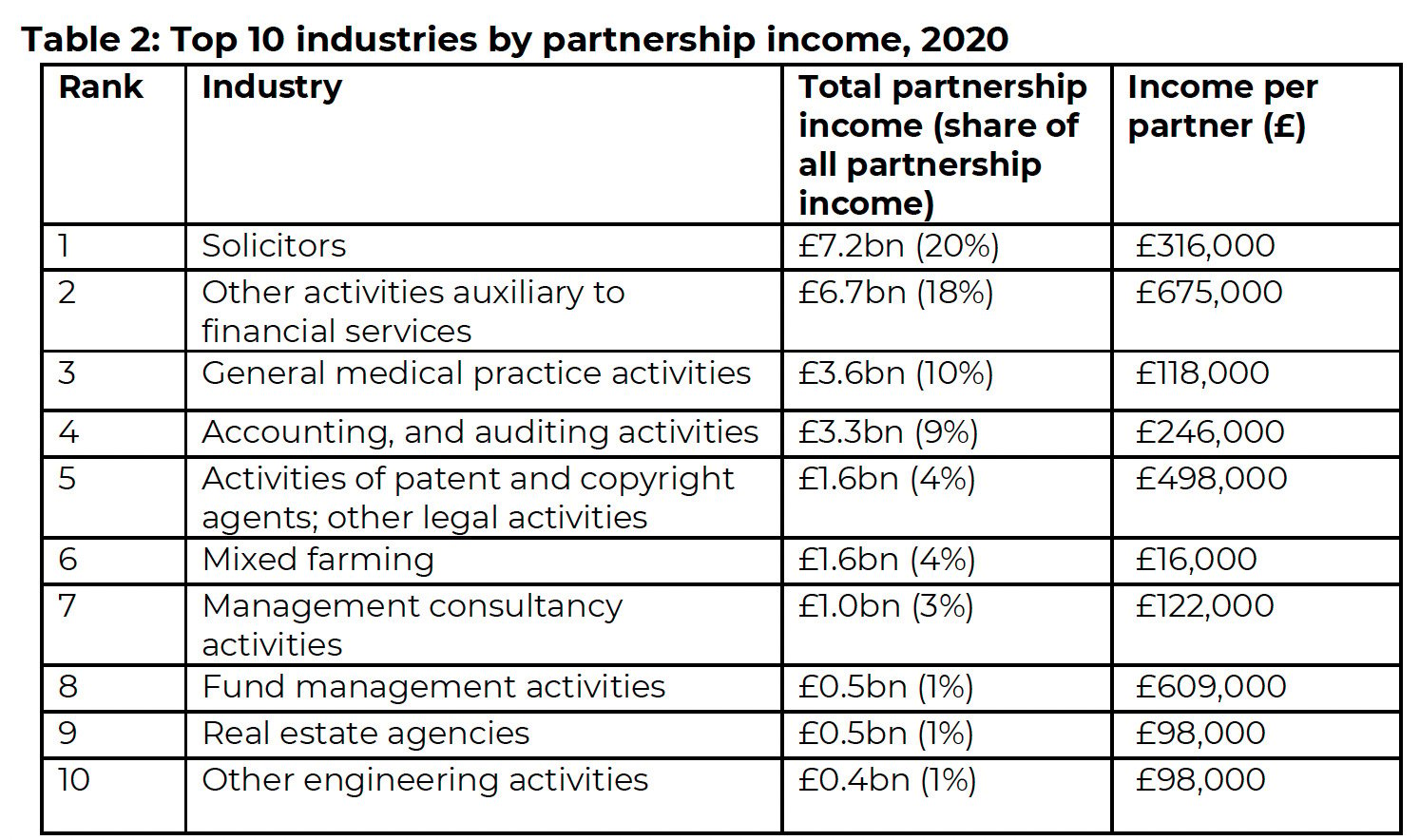

This is from the CenTax report:

Not shown on this table are much less profitable partnerships such as farm partnerships. CenTax proposes an allowance or exemption that prevents them being affected.

The greatest number (but not the highest earners) are solicitors. CenTax reckons the average income of solicitors who are partners/members of LLPs is £316,000.7

A solicitor whose gross income is £316k currently takes home about £180k. If his income was subject to employer national insurance, he’d take home £158k.8

This is a very big difference. His effective tax rate (i.e. overall tax divided by overall income) has gone up from 43% to 50%. His marginal tax (i.e. the % tax they pay on the next pound he earns) has gone up from 47% to 54%.9

We see more dramatic effects if we go to the largest law firms, where many partners earning well into seven figures.

A partner earning £2m currently takes home £1,072k. If employer NICs applied, she’d take home £934k – meaning £138k more tax. Her effective tax rate has gone up from 46% to 53% and her marginal tax rate is now 54%.10

This puts our £2m partner in the same position as (say) a trader at a bank where their salary and bonus pot are together £2m. Previously she paid less tax; now she pays the same.

An important point: the reason law firms are usually structured as partnerships is history rather than tax. Until relatively recently, solicitors were required to practice as partners or sole practitioners. Firms weren’t able to become companies until 1985. Even today, most of the big firms aren’t in practice able to incorporate because, whilst it would be permissible for their English lawyers, it’s not permitted for many of the foreign lawyers they practice with.

Similarly, auditors (and thus many accountants) historically had to structure as partnerships, and still do in some countries.

However many professionals absolutely do structure as partnerships for tax purposes. Most fund management businesses – private equity and hedge funds – are structured as LLPs rather than companies. The main, and perhaps only, reason for this is tax. Other businesses are in the same category, e.g. some estate agents and architect firms.

According to CenTax, the average member of a financial services partnership earns £675,000. There will be some earning ten or twenty times this figure. Someone earning (say) £6m would pay £414k more tax if employer national insurance applied to their pay.

The arguments for and against

There are several obvious arguments in favour:

- If the Chancellor is to stick to her fiscal rules then, absent very large spending cuts, she needs to find additional tax revenue. This is a relatively easy way of taxing high earners.

- It’s in principle correct that everyone who makes their living from work should be taxed the same way.

- This are complex rules to stop people disguising employment as LLP membership. Those rules could now be abolished.11

CenTax estimated that imposing employer national insurance on partnership members’ pay would raise around £2bn. Their analysis seems sensible to me – although it’s based on 2020 numbers so the figure today would be around 15-20% higher.

There are, inevitably, several arguments against.

Consistency – LLPs

The second Times article suggests the measure would only apply to LLPs, and not traditional partnerships. That seems hard to justify. One of the most profitable law firms in the country is structured as a traditional partnership, not an LLP. Can it be right they pay less tax because of this historical accident?

The original CenTax proposal looked at taxing partnerships generally; restricting any change to LLPs would be a bad mistake. Any rule which doesn’t apply to all professional tax-transparent vehicles will be unfair, economically distortive and – inevitably – gamed. We could expect large-scale avoidance, as firms seek to convert into either general partnerships or (more likely) foreign entities that have many of the benefits of LLPs but aren’t subject to the new tax rule. If ever there were sectors willing and able to structure their way out of a tax they don’t those sectors would be it’s accounting firms, law firms, and fund managers.

The more general consistency problem

More fundamentally: some lawyers practice as individuals. They wouldn’t pay employer NICs. That seems odd. If LLPs/partnerships result in much more tax than sole traders, we’ll (at the margins) see some people breaking away from firms to set up on their own. And some sole traders that would have gone into partnership, won’t.

What about barristers? Junior barristers at leading commercial barristers’ chambers can earn up to £360,000 in their first year. Some senior KCs earn ten times that. Barristers aren’t (usually) members of partnerships; but it’s hard to see why a barrister who earns £2m should pay less tax than a solicitor who earns the same.

This becomes quite hard to fix unless employer national insurance (or something equivalent) is applied to all the self-employed (and see further below).

Behavioural response

It’s easy to calculate the “static” revenue from a tax change – it’s just multiplying numbers together.

Estimating the actual revenue is much more difficult, because you have to take into account the “behavioural response”.

Here there will be several:

- Some people will move from LLPs and partnerships to become self-employed consultants (and escape the new tax). Sometimes this would be real. Sometimes this would be artificial avoidance – one could imagine a GP practice or law firm splintering into multiple “consultants” all claiming to be self-employed. New anti-avoidance may be required on top of existing rules.

- Large law firms practice all over the world. In many cases it’s possible to do much the way work in Dubai as in London. So (at the margins) we will see some members of these firms move from London to Dubai to escape the tax. And not just Dubai – for various reasons, lawyers in many European countries pay lower tax than lawyers in the UK.

- Some people will work less, because they are less motivated. Conversely, others will work more, because they need to work more hours/years to earn the same amount.

- Some firms will restructure into companies. The partners/members will become shareholders. On the fact of it this saves just a small amount of tax – my calculations suggest an average GP could save £3k, and even a £2m law firm partner would save only £13k. However in practice it may save more than this, as the companies could retain and reinvest profit. That may even have business and economic advantages.12

- And another response that won’t impact revenue: some of the incidence may be borne by firm employees, e.g. with employed lawyers receiving smaller pay rises than they otherwise would, and some by clients, in the form of increased fees.13

CenTax used historical “elasticity” data to estimate that imposing NICs on partnerships would cause a loss of tax revenue equal to about 20% of the “static” estimate. That feels in the right range.

The question is whether there would be a wider impact on UK law firms, fund managers etc, beyond just the loss of tax revenue, and perhaps a wider impact on the City and the economy as a whole. I don’t know the answer to that.

Complication

There will be, inevitably, complications in how this works. For example:

- Some of the return received by partners represents remuneration for their labour. Some is a return on capital. There would need to be some mechanic for differentiating between the two, without allowing people to over-allocate their remuneration to a capital return. The return on capital is currently usually quite small; that in part may reflect low risk, but may genuinely be less than it should be.

- Many of the largest law firms are single partnerships/LLPs, with partners/members all over the world. The new rules would have to only apply to distributions to UK partners/members – and sometimes particularly for US firms) the distributions are significantly of foreign profits which are taxed abroad and not here.14

- Fund management LLPs often stream fund returns as well as what is realistically labour income. Differentiating between the two may not be straightforward.

How a messy compromise could produce a principled result

I am not very good at politics, and try not to make political predictions.

That said: it seems to me there are likely to be few people opposed to the idea of increasing the tax of millionaire lawyers. There may be rather more people opposed to the idea of increasing the tax on GPs. A £6k cut in take-home-pay is likely to go down badly with GPs, particularly when compared with the (net) £2,000 increase they received from the most recent pay deal.

That raises obvious political questions: but exempting doctors from any new rule would be unprincipled. The Times is suggesting that might be the direction the Government is going, but that would be a serious mistake (for the reasons noted above re. consistency).

A better answer, suggested by CenTax, is for central Government to increase GP pay, funded by the new tax measure.

Or a more principled approach – and one which avoids revisiting the doctors’ pay deal – would be to create a per-partner/member exempt amount, set at a level so doctors pay little or no additional tax.

If the exempt amount were set at the average GP partner pay of £118,000, I estimate this would reduce the yield from about £2bn to about £1bn (calculation on the second tab of the spreadsheet).15

That kind of messy compromise could actually prepare the way for the most principled change of all: applying employer national insurance to all forms of work, employed and self employed. That’s clearly out of the question (at least politically) if we’re talking about the moderately paid self-employed (e.g. tradespeople). But if it’s done with an exempt amount, then suddenly it seems more realistic. We could apply to other forms of income too, such as rent.

And all this has the laudable side-effect of dealing with the consistency problems identified above. It might even pave the way towards abolishing national insurance altogether – the first step towards abolition is ensuring that everybody pays it.

Obvious disclosure: I was a partner in a large law firm. I have no economic interest in any law firms today, but it goes without saying I am going to be influenced by my background.

Front page © News UK / The Times, and excerpted for purposes of criticism and review.

Footnotes

This is just the latest in a long series of articles reporting on Budget speculation. The speculation is damaging and I wish whoever in the Government is responsible for the leaks would stop. ↩︎

Historically, many people have justified the lower tax on self employed and partners by saying they take more entrepreneurial risk than the employed. That is sometimes true – but not always. An employee in a small start-up is probably taking more entrepreneurial risk than a partner in a large accounting or law firm. And someone starting up a new business through a company will usually be taking much more risk – but their overall effective rate of tax (corporation tax and income tax) is usually much higher than that of a partner in a firm. ↩︎

See page 3 of the CenTax paper. ↩︎

Such as: student loans, childcare subsidies, pensions, return on capital – there are many more. ↩︎

Of course I’m simplifying; there are many other costs of employing people, not least pensions – but the conclusions are the same even if we cater for all the real-world complexity. ↩︎

It’s a surprisingly small difference, given that before tax she was £16k better off. The reason is the high 62% marginal rate on earnings between £100k and £125k. ↩︎

Obvious point: this is not the average earnings of solicitors – most solicitors aren’t partners. ↩︎

That’s because he is paying for the employer national insurance – it reduces his gross wage. You can see the calculations in the spreadsheet. ↩︎

A pedant might say that the employer national insurance isn’t his tax. That’s true in a pure legal sense – it would be the partnership paying the tax. But realistically, and in economic terms, it absolutely is the tax of the partners. ↩︎

The real rates may be higher than this – law firms often have significant non-deductible expenses, which tend to increase the effective and marginal rates beyond what one would expect. ↩︎

On the other hand there would need to be new rules differentiating between professional partnerships and other partnerships, e.g. passive investment partnerships. ↩︎

As partnerships/LLPs can’t reinvest profit without creating “dry” tax hit for partners. ↩︎

I suspect these effects will be small for law firms, given the very international environment they operate in. Associate remuneration has in recent years been heavily driven by the level of associate remuneration in the US; that dynamic seems unlikely to change. Increasing fees may be difficult for areas of work where English lawyers can advise from outside the UK. ↩︎

One solution might be to make the tax apply at the level of UK resident partners/members, so completely differently from normal employer’s national insurance. ↩︎

The disadvantage is that partnership is still a tax saving for people earning less than £118k. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Tom Blandford Cancel reply