Reports suggest Labour may introduce capital gains tax on home sales in the Autumn Budget. It sounds like an easy revenue raiser – but the evidence shows it would slash transactions, gum up housing chains, and could even collect less tax overall. With stamp duty already doing huge damage, the last thing we should do is add yet another tax on moving house. Particularly when there are better alternatives.

The current mess – stamp duty

Stamp duty land tax (SDLT)1 is a deeply hated tax.

(There are slightly different taxes in Scotland and Wales. The rates are generally higher, so we should expect all of the below to apply to Scotland and Wales, but more so)

If you tax something, you get less of it. Stamp duty taxes property transactions, and so we shouldn’t be surprised that stamp duty reduces property transactions.

It is, however, surprising quite how large this effect – “elasticity” – is. Office for Budgetary Responsibility figures shows that every 1% increase in the effective rate of stamp duty cuts transactions by about:

- 7% for properties under £250k.

- 4.5% for properties between £250k and £1m.

- 6% for properties over £1m.2

These are not theoretical figures: they’re measured from a big change in 2014, when the previous “slab” system of stamp duty created big changes in the effective rate of the tax at different price points. The observed effects were twice as big as anticipated.

We can use these figures to estimate the effect of abolishing stamp duty (which is another way of saying: the adverse effect that stamp duty currently has).

- A £200k property pays £1,500 SDLT.3 That’s only 0.75% of the purchase price – so abolishing stamp duty would increase transactions in such properties by 5.25%

- A £291k property (the average England house price) pays £4,550 SDLT. That’s 1.6% of the purchase price – so abolishing stamp duty would increase transactions by 7.2%

- A £440k property (an average detached house in England) pays £12,000 SDLT. That’s 2.7% of purchase price. So abolishing stamp duty would increase transactions by 12%.

- A £2m property pays £153,750 stamp duty. That’s 7.7% of purchase price. Abolishing stamp duty would increase transactions in such properties by 46%.

These four examples shouldn’t be regarded as existing in separate universes. The £2m market may feel a world away from the £440k market – but it’s in reality one market, and some house purchase “chains” will include both £2m and £440k houses. If someone at the top of a chain doesn’t sell, nobody else in the chain can complete. So a 46% increase in £2m transactions will facilitate additional £440k transactions, beyond the 12% figure that the £440k calculation above suggests.

Given there were 663,645 residential property sales in England in 2022/23, we are talking about a very large number of transactions being deterred by stamp duty – somewhere over 70,000 each year. Each of these deterred transactions has a cost, in reduced labour mobility, inefficient use of land, and reduced economic growth. We also shouldn’t forget the human cost: being unable to move house makes people miserable. A recent paper finds that the welfare loss of taxes like stamp duty exceeds the revenue they raise.

And the rates are now so high that the top rates raise very little; HMRC believes that increasing the top rate any further would actually result in less tax revenue.

The effects aren’t limited to homeowners. Because SDLT depresses transactions, it reduces the rate at which developers at which developers can sell, therefore delaying their recycling of capital into new housing supply, and tightening the pipeline of new homes.

So there is a powerful case for abolishing stamp duty.

There are, however, two problems.

The obvious problem is that it raises too large a sum to simply be abolished. Any increase in transaction volumes would itself generate tax revenues from other sources (e.g. VAT on estate agent fees) but these effects are much smaller than the cost of the abolishing stamp duty.4

The deeper problem is that abolishing stamp duty would raise prices. Evidence suggests about 40% of any tax cut would be pushed straight into prices.

CGT – making things worse

The Times and Financial Times suggest the Government is considering imposing capital gains tax at 24% (higher rate taxpayers) or 18% (basic rate) on sales of people’s homes.

It’s obvious why this is attractive to politicians looking for tax revenue – the capital gains tax exemption for main residences is the single largest tax relief, costing £31bn.

However abolishing the relief would be as damaging as stamp duty – perhaps more so.

Imagine someone who bought an average detached house in 2010 for £250k. It’s now worth £440k. They want to move to another house of about the same value – perhaps to take up a job elsewhere, perhaps to join their family. Today there’s stamp duty of £12k – and that’s already a problem. But if CGT applied there would be a gain of £190k and capital gains tax of about5 £45k. For most people that would be unaffordable. The OBR stamp duty figures imply that transaction volumes would fall by over 45% – and this kind of “lock-in” has been observed in other countries.6

So no developed country in the world does this.

Most countries – e.g. France, Germany, Australia, Denmark, Ireland, have a simple exemption, like the UK. Others – e.g. Switzerland, Sweden, let you defer the gain if you’re buying a new residence (so the gain is taxed only if/when you sell a residence without buying a replacement).7

The US exempts the first $250k of gain ($500k for married couples). Deferral is available for investment properties, and so a common strategy for owners of high value properties is to “convert” their home into an investment property in advance of a sale.

What if we only impose CGT on high value properties?

It might seem politically tempting to adopt some variant of the US approach, so that high value properties are taxed, and others remain exempt. The Times has reported that the Treasury is considering capital gains on sales of over £1.5m.

Introducing a “cliff edge” at which gains start to be taxed would be unfair and highly distortive. And taxing historic gains feels like retrospective taxation (but if the government didn’t do that, and only taxed future gains, revenues would be very small). However, even if we leave these significant points aside, the mathematics of such a tax are challenging.

Take an example where a £2m house is sold at a £750k gain.

Today there is £153,750 of stamp duty (paid by the purchaser) and (in most cases) no capital gains tax for the seller. But imagine that the £750k becomes a taxable gain for the seller:

- The seller would face a £180k CGT liability.

- That’s great – lots of new tax raised!

- But the tax will deter some people from selling. We can conservatively8 use the OBR SDLT data to quantify this effect. £180k is 9% of the purchase price, and so the OBR figures suggest that would result in a 54%9 drop in transactions (more in the short term).

- So, for each transaction before the CGT change, we’re now seeing 0.46 transactions, generating total tax of £153,525 (i.e. 0.46 x (£153,750 + £180,000)).

So we haven’t raised £180k of new tax at all – we’re taking in £225 less tax.

This is just an illustrative example: if the gain had been smaller then some net tax would have been raised, but the high elasticity and much higher stamp duty means the net tax is always much smaller than one would expect.

For example, if instead of a £750k gain, there was a £10k gain, there would be £2,400 of CGT – but the resultant small (but significant) decline in transactions means the net revenue is about half that figure.10

And of course if the gain had been larger then there would be a larger loss of net tax revenue. If, instead of a £750k gain, there was a £1m gain, there would be £240,000 of CGT – but a 72% fall in transactions meaning a net revenue loss of £43,500.11

It’s counter-intuitive, but the property owners with the largest gain, where one would expect the most tax to be raised, actually cause revenue losses.

There will be second order tax revenue effects (lost VAT on fees for the transaction that is no longer happening) or the wider effects to the property market and economy. As discussed above, some house purchase “chains” will include both £2m and £440k houses. Chains propagate “shocks” across the market; if £2m transactions fall by more than 50%, we should expect the rest of the housing market to be affected.

All of this will be exacerbated by the fact that CGT is wiped-out at death – so people sitting on large gains have a powerful incentive to never sell (their estate will pay IHT either way), further gumming-up the housing market.12 It will be exacerbated further if people believe that a future government would change the law – why sell now, if CGT might disappear in two years’ time?

The fundamental point is that, given the high elasticity, adding more tax on property transactions is well past the point of diminishing returns.13

The Treasury know all this. We’re not going to see CGT on our homes.

So what’s the answer?

We could replace stamp duty and council tax with a modern land value tax (LVT) – an annual tax on the undeveloped value of land. Because it’s not a tax on transactions, it doesn’t deter transactions. It would prevent the abolition of stamp duty triggering a rise in prices. It encourages developers to build/sell as quickly as possible. It also has significant economic benefits, which are recognised by economists across the political spectrum: how many other ideas are backed by James Mirrlees, the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Adam Smith Institute, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the New Economics Foundation, the Resolution Foundation, the Fabian Society, the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and the chief economics correspondent at the FT?

However LVT faces some serious challenges:

- Like any significant tax reform there would be winners (people who expect to move house) and losers (people who don’t). That could make it a hard political sell. The politics may be easier if the reform as a whole was revenue-neutral – but current fiscal pressures mean there is little political appetite for revenue-neutral tax reform.

- There would need to be transitional rules – otherwise people who’d recently paid a large stamp duty bill would feel they were being taxed twice. We could, for example, credit recent stamp duty bills against future land value tax payments.

- The balance between local and national taxation would need to be entirely redrawn.

- And the whole regime would probably need to be phased in, to avoid price shocks.

There have therefore been few attempts to propose a detailed and viable LVT implementation for the UK.

There was, however, a recent very detailed proposal published by by economist Tim Leunig for centre-right think tank Onward. This wasn’t an LVT, but what Mr Leunig calls a “proportional property tax”. It’s a serious and well-thought-out proposal which would (broadly speaking) replace council tax with (on average) a 0.44% annual tax on property value below £500,000, and replace stamp duty with a national levy of 0.54% on property values between £500,000 and £1m, and 0.81% on any value above £1m.

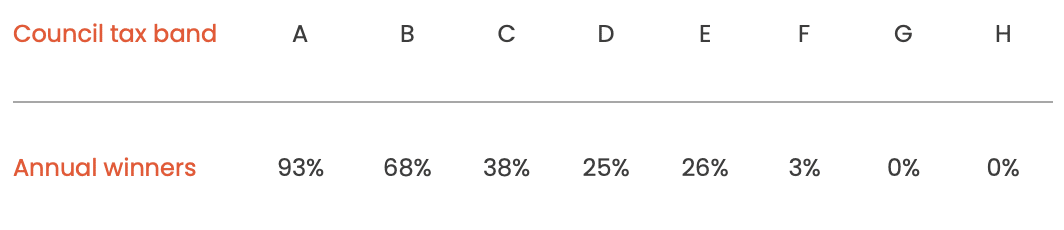

There would, once more, be winners and losers. Mr Leunig is commendably up-front about this, showing the percentage of “winners” in each council tax band:

I fear that telling three-quarters of average households that their annual property tax is going to increase will be a hard political sell. The pain would be eased by making the £500k+ national levy only apply to houses purchased after the tax comes into force – but that has the obvious potential to stall the market in £500k+ houses (and, to be fair, the Onward report acknowledges this issue).

Whilst I applaud the detail and rigour of Mr Leunig’s report, I am doubtful it could be implemented in its current form – but elements of it are well worth detailed consideration. So when The Guardian says that Treasury officials are “drawing on the findings” of the Leunig proposal, that’s promising news.

Photo by Richard Horne on Unsplash

Footnotes

Apologies to all tax professionals, but I’m going to call SDLT “stamp duty” throughout this article. ↩︎

These are the long run transaction semi-elasticities in the OBR paper. ↩︎

This and the other figures in this article use the standard SDLT rates and ignore all the many potential complications. In particular, I’m ignoring the 2% non-resident premium, the special <£300k rate for first time buyers, and the 5% higher rate for second/subsequent properties. All these factors would tend to increase the effects I discuss. ↩︎

We can illustrate this with a back-of-the-napkin calculation. Abolishing stamp duty would result in around 70,000 additional house sales. Estate agent fees on these would be around £300m (70,000 x 1.5% x £285k), with VAT of £60m. There will of course be other effects, but we’re more than two orders of magnitude too small to overcome the cost of abolition. ↩︎

The precise figure depends on their tax band, but most of the sale will be taxed at the higher rate regardless. ↩︎

In practice the impact would likely be worse. Elasticities are often not linear: a large, sudden and well-publicised increase in a tax often has a much greater effect than a simple elasticity calculation would suggest. ↩︎

The way this works is that, in the above example, there would be no capital gains tax on the purchase of the £440k house, but the new house would “inherit” the old purchase price of £250k. So if the new house was sold for £440k, and not replaced with another residence, the deferred CGT of £45k would be charged. ↩︎

Conservative because SDLT has two effects: it makes buyers pay less (price elasticity) and deters purchases (transaction elasticity). CGT will only have a transaction effect, so we’d expect the transaction elasticity to be higher than for SDLT. ↩︎

i.e. 9% x -6.0 ↩︎

Stamp duty still £153,750, CGT is 0.12% of purchase price, so there’s a 0.72% decline in transactions. 0.72% of £153,750 is £1,107. ↩︎

Because £240,000 is 12% of £2m, so there’s a 72% fall in transactions, and 72% of £153,750 is £110,700. ↩︎

Although this will be a significantly smaller effect than stamp duty. Stamp duty defers all transactions. CGT only deters sales at a high gain. ↩︎

That wouldn’t be the case if the tax rate was low, say 5-10%. A small amount of tax could then be raised without adverse effects – but query if raising small amounts in this way is a worthwhile endeavour. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Chris Dean Cancel reply