A UK wealth tax is often promoted as an easy revenue-raiser that would only affect the very rich. Our analysis finds the opposite: the revenue is highly uncertain, and would arrive only after years of complex implementation. Most importantly, the tax would lower long‑run growth and employment, thanks to a decline in foreign and domestic investment. It would make UK businesses more fragile and less competitive, and create strong incentives for capital reallocation and migration. There are better solutions to the many problems with our tax system.

The numbers that change the wealth tax debate

2–5% GDP

Modelling of comparable proposals shows long‑run GDP hits ~2% (US) to ~5% (Germany).

More.

80% / £4bn

~80% of projected receipts come from ~5,000 people; ~15% (£4bn) from the top ten.

The revenue is fragile. More.

60%+

A 2% wealth tax can push marginal effective rates above 60% — and above 100% on low‑return assets. More.

2029

Unlikely to see any revenues before Jan 2029. Too complex and slow to implement. More.

This report summarises the UK wealth tax proposals, analyses the claimed revenue yield, and looks at the potential downsides and risks, and the policy alternatives. We compare the new proposed wealth tax with the older wealth taxes that have largely failed and been repealed. Finally, we suggest better and less risky ways to tax wealth in the UK.

Executive summary

This very brief summary links at each point to the detailed analysis below. You can also navigate with these buttons:

1. Economic impact: growth, investment, startups

- Wealth taxes are anti-growth. Penalise saving & capital formation. Effective tax rates can exceed 60%+ for modest‑return assets. High effective rates. Growth impact. Employment impact.

- Evidence. International modelling of comparable proposals shows ~2% (US) to ~5% (Germany) long‑run GDP hits, plus large impact on employment; UK exposure may be greater. US studies · German study.

- Startups & capital‑intensive firms face liquidity squeezes. Owners may be forced to sell or pull cash from the business. Valuation difficulties. Liquidity problem · Capital‑intensive impact.

- Higher dividend payouts to fund tax mean lower reinvestment. Evidence from Norway & other studies. Dividend response.

- Foreign direct investment would fall. Tax must catch foreign owners or is easily avoided. That deters future FDI and prompts withdrawal of current FDI. FDI analysis.

- Makes UK business uncompetitive. Because a UK Ltd’s foreign subsidiaries are subject to the UK wealth tax; its foreign competitors are not. Competitiveness.

- Worsening recessions. In a downturn, capital and the taxes on it usually fall automatically – “automatic stabilisers” for the economy. Wealth tax bills barely change. Wealth taxes provide a shock during periods of financial stress.

- These factors are both more consequential and more complex than the “will they leave?” debate that’s currently playing out in the media.

2. Revenue risk: headline sums are fragile

- Claims of £10bn to £25bn a year revenue rest on optimistic behaviour assumptions. Using higher (still plausible) avoidance/migration elasticities cuts receipts sharply. Revenue analysis. The numbers.

- 80% of projected yield comes from ~5,000 people; ~15% from ten people. A handful changing residence or valuations could remove billions. Migration risk. Worse than non-dom response.

- Even proponents’ “low response” scenario implies £200bn of lost capital; “high” ~£500bn. That erodes other tax bases. Capital at risk.

- Historic data are misapplied. Past wealth taxes had low rates, wide exemptions and applied broadly; new UK proposals are the opposite. Compare designs.

- The UK would be an outlier. No developed country in the world has both a significant wealth tax and a significant inheritance tax. Nobody has implemented a wealth tax of the type proposed. International comparisons.

- Requires an unprecedented wealth exit tax to stop large-scale capital flight. But fear of an incoming wealth exit tax would trigger a wave of exits, and the tax would deter entrepreneurs and others from coming to the UK. Undermines the Government’s new FIG regime. Wealth exit tax.

3. Implementation & better options

- Complex to legislate & administer. Realistically multi‑year build; no cash until January 2029. Implementation timeline.

- Existing wealth taxes abroad work only with big carve‑outs. Spain exempts business assets and collects very little – a deliberate decision of a socialist government to minimise economic damage. Norway/Switzerland heavily discount or cap. International evidence.

- Valuation creates an administrative burden far beyond that seen in income or consumption taxes. Valuation difficulties.

- Fix current UK wealth taxes instead. Reform land tax, capital gains tax, and inheritance tax. All could raise revenue more fairly, more efficiently and faster, with fewer risks. The UK needs tax reform across a swathe of existing taxes. Policy alternatives.

- The apparent polling support for wealth taxes is fragile, based upon questions that provide no context and reveal no trade-offs. The mansion tax was popular – until it wasn’t. Polling.

Bottom line: An annual UK wealth tax is a high‑risk, low‑certainty revenue bet that could harm growth. Better‑targeted reforms can tax wealth more effectively with far less collateral damage. See our recommended reforms.

The rest of this report explores all these points in more detail.

What is being proposed?

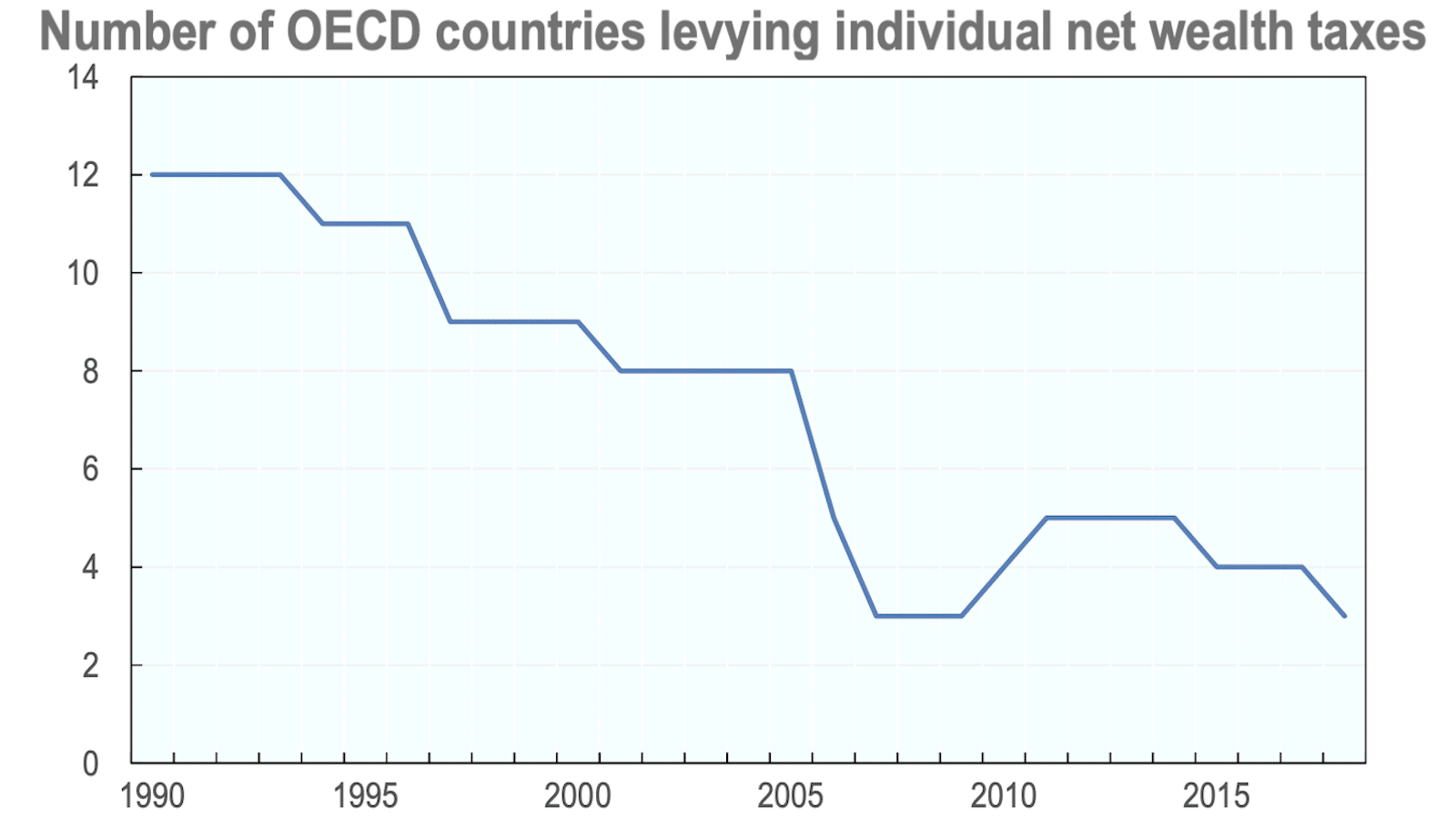

There have been many attempts to introduce wealth taxes, with a first wave of taxes in the 1890s and 1900s1, and a second wave after WW22 Wealth taxes were largely abandoned by the 2000s, with only three remaining in Europe.3

Historic and existing wealth taxes have low rates, and/or wide exemptions, and were easily avoided; but that also means they had limited adverse economic impact.

The new “third wave” wealth tax proposals aim to raise much larger sums by eliminating all exemptions, and ease political objections by only applying to the very wealthy.

Some of the highest profile proposals are:

- Tax Justice Network: a 2% on wealth over £10m, raising £24bn. This appears the most widely supported proposal, with backing from Oxfam, Dale Vince and the “Patriotic Millionaires” campaign.

- Unite: a 1% on wealth over £4m, raising £25bn.4

- TUC: 1.7 % on wealth over £3m, 2.1% on wealth over £5m, and 3.5% on wealth over £10m – intended to raise £10bn.5

- Green Party: 1% on wealth over £10m and 2% on wealth over £1bn, intended to raise £15bn.6

All share the key feature that, unlike all existing and historic wealth taxes, there will be no exemptions of any kind, and the taxes only apply to a small number of taxpayers. However, at the same time, the proposals all rely on behavioural response data from these old wealth taxes, which applied to many more taxpayers and had exemptions to prevent adverse economic impact.

None of these proposals even acknowledge the potential for adverse economic impact.

By far and away the most serious UK analysis of wealth taxes was from the Wealth Tax Commission, an informal body of academics and tax policy experts which was convened in 2020.7 It recommended against an annual wealth tax and in favour of a one-off retrospective tax. The one-off tax proposal has very different effects to the other current wealth tax proposals, and we consider it at the end of this report.

Most of this report will focus on the Tax Justice Network proposal, because it is the clearest about its mechanics and methodology (taken from the work of the Wealth Tax Commission). However the criticisms we make apply to all the current wealth tax proposals.

Isn’t a 1% or 2% wealth tax tiny?

A wealth tax is often described as a “tiny” or “small” tax. And a 2% tax on income is indeed a small tax, unlikely to prompt dramatic action in response from most taxpayers.

A 2% tax on wealth, on the other hand, is very different.

There are two ways to look at it.

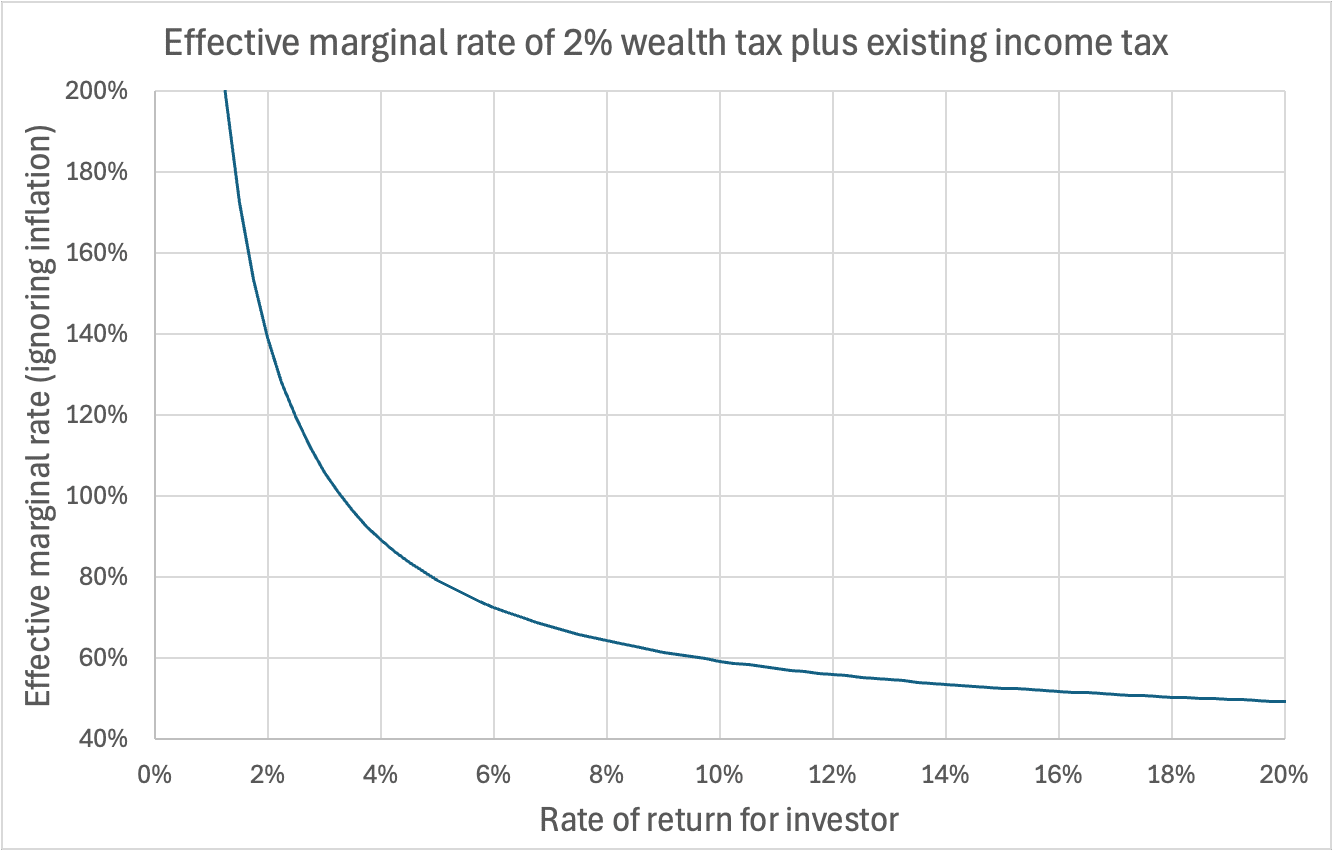

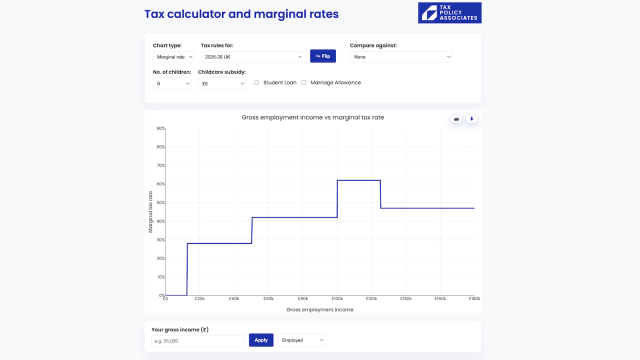

First, as increasing the overall effective rate of tax on the return on assets:

For an investor earning an 8% return8 on their assets over £10m, a 2% wealth tax on top of the existing 39.35% dividend tax creates a marginal effective rate9 of 64.35%.10 If, as we should, we take corporation tax into account, then the overall effective rate is 79.5%.11

For the owner of a business yielding a 4% return, a 2% wealth tax on top of dividend tax creates a marginal effective tax rate of 89.35% – or 104.5% if we include corporation tax. On the other hand, if the business yields a 15% return, the effective rate is 52.7%, or 69% after corporation tax.

So the more profitable the business, the lower the effective rate of tax:

This is counter-intuitive. It’s also the opposite of what optimal tax theory says a tax should do, and is one of the reasons the Mirrlees Review said there was a “persuasive economic argument” against the wealth tax. There is a clear explanation of these effects from the US Tax Foundation here.

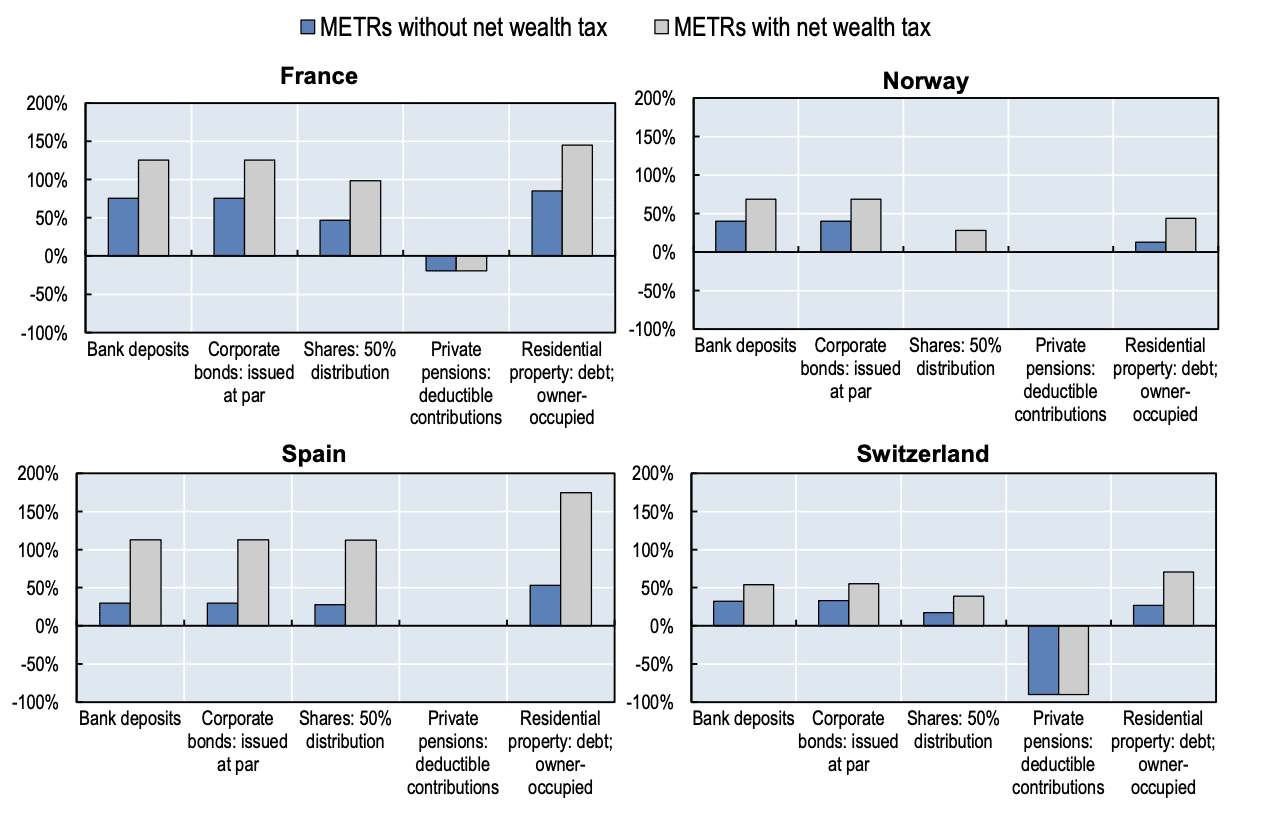

We can see these effects in action in an OECD analysis of the marginal effective tax rates of the then-existing wealth taxes in 2016:12

The charts are a little out of date – Spain now has a “cap” which reduces the wealth tax if it would raise the overall effective rate of tax above 60%. We discuss this further below.

The proposed UK wealth taxes have a higher rate than these taxes and no caps or exemptions: the effective rate will therefore be greater than shown in these charts.

Second, as a one-off reduction in the value of an asset.

Because the wealth tax is an annual tax, it amounts to a permanent change in the economic characteristics of assets.

Take someone who owns a £100m company, now subject to a 2% wealth tax. If they expect an 8% return on their holdings, the wealth tax has reduced the value of the company by £25m (i.e. because their return from the £100m company, net of wealth tax, is the same as what their return would have been from a £75m company before the wealth tax).

What this means

A taxpayer’s response to a tax will be driven by the cost to them of that tax. If the cost was really “tiny” we would expect little response. But the nature of the wealth tax means that the cost is actually much higher than existing UK taxes – and so we should expect a heightened response.

The existing real world wealth taxes generally mitigate all of these results with exemptions, discounts, liability caps, valuation safe harbours and other special rules. The proposed new wealth taxes contain none of this. So we should also expect a much higher response than we see from existing wealth taxes.

And the effective rates discussed above will be increased by the cost of complying with the tax. This is highly uncertain – estimates in the Wealth Tax Commission papers range from 0.05%13 to 1.5%14 of net wealth.

A final point: the cost of the wealth tax will extend beyond the taxpayers who are subject to the wealth tax. To prevent avoidance and evasion, HMRC would realistically have to require a wealth tax return for people with assets approaching the threshold. So if the threshold is net wealth of £10m, around 32,000 taxpayers would pay the tax.15 But another 16,000 would have net wealth above £7.5m16, and likely would be required to submit returns, and incur material expenditure on compliance.

Will it raise the claimed sums?

Wealth tax proponents present their revenue projections without acknowledging what serious researchers have always made clear – there is a huge amount of uncertainty as to how taxpayers will respond to these taxes, and what that means for the revenue they will raise. The Wealth Tax Commission paper on behavioural response noted that estimates of taxpayer response in the literature vary by a factor of 800.

However, the basic problem is simply stated. We expect that no tax in the history of the world has relied as heavily as the new wealth tax proposals on collecting so much tax from a small number of people. 29% of UK income tax is paid by the highest earning 1%. Two thirds of Norwegian wealth tax is paid by the wealthiest 1%. But the proposed Tax Justice Network UK wealth tax would raise all its revenue from the top 0.1%.17 About 80% of wealth tax revenue would come from the wealthiest 5,000 people18, and around 15% of wealth tax revenue from just ten individuals.19

That makes the tax uniquely vulnerable to a very small number of people responding to the tax, either by gaming valuation (for which see further below) or ceasing to be UK tax resident.

Migration

The most obvious way to escape the wealth tax is to cease to be UK tax resident.

For the merely very wealthy (£10m to £50m), that may actually mean leaving the UK – never an easy undertaking, practically, emotionally and financially. Anyone with material UK wealth who wishes to escape the wealth tax would need to not just leave the UK, but exit their UK assets. Where assets are illiquid (private company shares and real estate, for example), this would be neither straightforward nor speedy.

However, when it comes to the extremely wealthy – say the approximately 5,000 people with wealth of £50m or more, or the much smaller number of billionaires, things are very different. Talk of such people “leaving” is simplistic – they often have homes in several different countries, spending a few months in each one. UK rich lists are dominated by people who came to the UK from abroad and spend comparatively little time here. Ceasing to be UK tax resident will in many cases mean adjusting diaries to spend no more than 90 days (or in some cases 120 days) in the UK. 20

It’s sometimes denied that the wealthy move countries to save tax (often based around studies of US state taxes). Our response: Sir Jim Ratcliffe (Ineos), Guy Hands🔒 (private equity), Lewis Hamilton (racing), Tina and Philip Green, the Barclay brothers, Richard Branson, David and Simon Reuben (property), John Hargreaves (Matalan), Terry Smith (fund manager), Steve Morgan (housebuilder Redrow), David Rowland (financier), Joe Lewis (Tavistock Group), Anthony Buckingham (Heritage Oil), David Ross (Carphone Warehouse), Mark Dixon (IWG), Douglas Barrowman (tax avoidance schemes), Alan Howard (hedge fund), Simon Nixon (moneysupermarket.com), Jonathan Rowland (property). There are many more.21

Any realistic analysis has to recognise the existence of tax exiles, and therefore acknowledge that a disproportionate number of very wealthy UK taxpayers have moved abroad to escape UK tax. Some estimate that one in seven British billionaires now live in tax havens; others one in three.

One final point: existing migration to avoid capital gains tax and income tax on dividends is restricted by a rule that you have to leave the UK for five years (or you are a “temporary non-resident“).

Migration to avoid the wealth tax would be immediately effective. Wealthy people could pop out of the UK just before a wealth tax came in, with the intention of returning if the wealth tax was subsequently repealed.

So we have no doubt that people will leave – some in the usual sense of the word, some in the technical sense of ceasing to be UK tax resident, but not dramatically changing their lifestyle. And the extreme reliance of the tax on a small number of taxpayers means that just ten people leaving would reduce wealth tax revenues by £4bn.

That means many wealth tax proponents say a wealth tax has to be accompanied by an exit tax.

Can a wealth exit tax stop migration?

The UK doesn’t currently have an exit tax. If you are (for example) a UK resident who is about to sell a large shareholding and make a substantial gain, you’d pay capital gains tax on that gain. But if you leave the UK, moving say to Monaco, you pay no capital gains tax (provided you stay outside the UK for five years).

A capital gains exit tax would trigger an immediate tax charge upon leaving the UK – as if you sold your shares (probably with an option to defer and complex credits against foreign taxes).

The US has a capital gains exit tax which is very harsh and effective – it can do that because the US taxes on the basis of citizenship not residence (see further discussion below). Many European countries have exit taxes which are less effective: in part because of EU law restrictions, and in part because (in short) they are not the US.

There are good arguments for reforming CGT so that we don’t tax gains people make before coming to the UK, but do tax gains they make when here – such a capital gains exit tax could be good policy, but would have to be implemented with care.

However a capital gains exit tax won’t be effective to deter people leaving to escape a wealth tax. If someone has few uncrystallised gains then they will be little affected by an exit tax.22 Even someone with large potential gains may regard the cost of the exit tax as a good deal compared to the wealth tax – CGT is 24% but many will always have anticipated and accepted that. If an exit tax is to be effective in stopping escape from a wealth tax, then the exit tax needs to do more than crystallise gains – it has to impose a one-off charge on net wealth similar to the future wealth tax charges that exit would avoid – a “net wealth exit tax“. That is a very different kind of exit tax, and one which very few countries have implemented.

Implementing an exit tax of any kind is a high risk endeavour. If the belief takes hold that the Government will introduce an exit tax then people will leave before the exit tax bites; even speculation about exit taxes can be economically damaging. A net wealth exit tax would have a more dramatic effect. Norway recently introduced such a exit tax to protect its wealth tax – and it experienced an immediate wave of exits.

There are also second order effects, after the tax is implemented, as people respond to its existence. UK residents may accelerate plans to leave the UK (or create such plans) because they worry about assets/gains that are anticipated but not yet acquired/accrued.

A net wealth exit tax would make coming to the UK a very consequential decision, and perhaps a financially irreversible one. We should therefore expect a decline in the number of wealthy people coming to the UK and, perhaps more importantly, a decline in the number of people who hope to become wealthy. That would be the opposite of the Government’s intention when it created the new “foreign income and gains” (FIG) regime to make it easier for high-skilled workers to move to the UK.

All of this means that an exit tax is not an easy answer, and comes with its own costs. And no exit tax would realistically apply to foreign residents with UK assets (as that would be correctly seen as a form of capital control, with a significant adverse impact on current and future foreign investment). We therefore once more see the problem of UK residents being put at a competitive disadvantage vs foreign residents with UK assets. And there is, once more, no obvious solution.

It’s not a repeat of the non-dom debate

The wealth tax debate is currently being reported in much of the media as a replay of the non-dom debate. But the impact of wealth tax migration is very different.

A non-dom can leave the UK without selling their UK assets and business interests, because once they become non-resident they won’t be taxed on those assets/business (unless it’s real estate investment). So the loss to the UK (in tax and economic terms) of the non-dom leaving the UK may be limited to the loss of their personal spending.

By contrast, someone migrating to escape the wealth tax would likely have to sell all their UK assets and exit all their UK business interests.23 We should therefore expect the tax and economic loss resulting from a wealth tax exit to be more significant than that from a non-dom exit.

How much do these effects reduce revenue?

The Tax Justice Network claim of £24bn of revenue from their wealth tax assume a “taxpayer behavioural response”, i.e. migration and other avoidance, of 14%. In other words, for each percentage of wealth tax, reported wealth falls by 14%.

This figure comes from the Wealth Tax Commission24, which estimated a behavioural response for a 2% wealth tax ranging from 14% (in a “low avoidance scenario”) to 34% (in a “high avoidance scenario”). The proponents use the 14% figure without any justification. But if the 34% figure was used then the revenue raised would be significantly less – £18.5bn.

We would first pause and note what these figures mean. In the “best case” 14% scenario, £200bn of wealth is lost (to migration and shifting into hard-to-value and unproductive assets25). In the “high avoidance” 34% scenario, £500bn of wealth is lost. These are very large numbers – and the nature of the current wealth tax proposals means they represent “real” taxpayer response, not just paper transactions.26 So there would be an impact on tax revenues (income tax, capital gains tax and VAT) as well as the economy as a whole.

The 14% figure seems very optimistic. Wealth tax proponents Saez and Zucman expected a 15% level of avoidance for a US wealth tax, when the US has citizenship-based taxation that often makes exit extremely costly.27 It would be surprising if the UK, where exit is so much easier, experienced less avoidance.

We believe the 34% figure may also be optimistic. All of these figures are based on studies of historic and existing wealth taxes – these had generous exemptions, and applied to a much broader class of taxpayer.28 It then applies the conclusions of these studies to the new wealth tax proposals, which have no exemptions, apply only to a small number of very wealthy and very mobile people.

There is good reason to believe that taxpayer response to tax rates is highly non-linear – we should therefore expect the very high effective tax rates created by the new wealth tax proposals to have a larger effect than a simple linear extrapolation would suggest (and much larger than other tax reforms we have proposed, which have far smaller effective rates). Given the large effect, and the relative ease of exiting UK tax residence, the experience of historic wealth taxes in other countries is in our view a very poor guide to how the new wealth tax would work in practice in the UK.

We therefore expect the revenue would be significantly less than £24bn. That might not matter if the tax would have no economic downside – but the evidence suggests that the economic consequences are likely to be both complex and serious. The wealth tax is not a costless bet which only has a positive upside.

What’s the economic impact?

Foreign investment

A UK wealth tax realistically has to apply to foreign residents owning UK businesses, as well as to UK residents. Otherwise we’d be making migration much easier (as an individual exiting the UK could keep all their UK shareholdings). We’d also be giving an unfair advantage to foreign-owned companies29, and causing UK businesses to be sold to foreign owners, to whom they would be more valuable. In our example above, a business that was worth £100m before the wealth tax would be worth £75m to private investors after the wealth tax – but if the wealth tax doesn’t apply to foreigners, it would still be worth £100m to them.30

But this creates a problem. Imagine you’re a French privately-owned business (or investor) considering investing €100m in either Germany or the UK. The UK investment will trigger a €2m annual wealth tax. Depending on how you view this:

- the UK investment would have to yield a 2% higher return than the German asset just to be equivalent to it, after wealth tax, or

- if you’re taking a long-term view, the wealth tax is equivalent to an immediate €25m loss of value (if we assume an 8% rate of return). You’d be paying €100m to obtain a €75m asset.

The German investment doesn’t have these consequences.

The same calculation applies to a privately-owned French company that invested €100m in the UK before the wealth tax. Its return is now 2% lower; it has the return of a €75m asset. So the rational move for the French company is to pull its €100m from the UK and move it to a country without a wealth tax.

Most existing wealth taxes don’t have this difficulty, because they pragmatically contain exemptions. The Spanish tax exempts unlisted company holdings. The Swiss and Norwegian wealth taxes apply only to non-residents if they own local real estate. But the ambitious modern wealth tax proposals realistically have to apply to non-residents. And that’s a problem.

British competitiveness abroad

Under the wealth tax, UK owners of a business abroad will pay a 2% wealth tax on the value of that business.

This creates a competitiveness problem.

A privately held UK company31 with a subsidiary in (say) France will pay32 a 2% wealth tax on the value of the French business. Its French-owned competitor will not.

A UK-owned foreign business would therefore require a higher internal rate of return than foreign-owned rivals to deliver the same post-wealth-tax yield. The UK-owned business may become uncompetitive. Projects or acquisitions that clear the hurdle for a French or US buyer may be rejected by a UK buyer.

The impact on growth

There are different views on whether historic wealth taxes impacted savings and investment, and therefore growth. However these wealth taxes were easily avoided by arrangements with little economic effect (for example restructuring investments through a private company, or even just failing to declare assets).

The new proposed wealth taxes are intended to be very hard to avoid – the most realistic avoidance strategies are moving into hard-to-value assets or migrating. These strategies do have real economic effects.33

The new wealth tax proposals have several effects that impact growth:

- The tax makes savings and investment less attractive for UK investors and business-owners, and consumption more attractive.

- The fact that the wealth tax has a higher effective rate for less profitable businesses means it increases the risk and the cost of failure (as well as the cost of owning a startup).34 It therefore makes entrepreneurship less attractive. A study by Hansson⚠️ found that existing wealth taxes caused a 0.2% to 0.5% fall in self-employment. That’s surprising given that these taxes generally exempt business assets. We should expect much larger effects with the proposed new wealth taxes.35

- For privately-owned foreign investors into the UK, a wealth tax will disincentivise investment, for the reasons set out above. This is a significant concern given the UK’s reliance on foreign direct investment (FDI) – the UK’s inward FDI stock is equivalent to about 87% of GDP (one of the highest in the world, and beaten only by Hong Kong and Singapore).

- And another effect on both foreign and domestic business owners: when they can, they’ll take dividends from their businesses to fund wealth tax payments. That means less retained in the business for investment. An analysis by Ebeltoft and Johnsen⚠️ found that the Norwegian wealth tax, 0.5% at the time, elevated dividends by 7.8%. A study by Fuest, Neumeier, Stimmelmayr and Stöhlker into a proposed German wealth tax (at half the rate of most of the proposed UK wealth taxes) found that it would result in a 5% decline in production and a 10% decline in investment.

- This effect isn’t limited to privately held companies; public companies respond to the need for their investors to fund wealth taxes. An analysis across 26 countries by Barroso, N’Gatta and Ormazabal found that wealth taxes were associated with significantly larger dividend payouts and reduced investment.

- More subtly, a wealth tax will distort investment towards assets that are hard to value – such as art, expensive/vintage cars, yachts, jewellery. If investments in these assets increase, and investment in actual capital decrease, then that reduces savings and reduces productivity.36

- Migration to avoid the wealth tax – which we discuss below – will have additional effects in terms of lost investment and jobs, but that may be less important than the above “intensive margin” effects.37

- All these effects will be heightened during an economic downturn. Investors’ returns will reduce, but the value of their assets will decline only slightly – so their wealth tax liability will remain unchanged (and the inevitable delay between valuation and payment of tax mean that there may be no decline at all for wealth tax valuation purposes). The effective rate of the wealth tax will therefore rise – increasing all the effects discussed above. The wealth tax may, therefore, make recessions worse.38

Analyses of US wealth tax proposals

The call for implementation of wealth taxes by Elizabeth Warren and others in the US, led to several detailed economic analyses of these effects. The Penn Wharton Budget Model and the Center for Public Finances found that these proposals would reduce long-run GDP by over 2% if the funds were (as is proposed for the UK wealth tax) used to finance current expenditure.3940

How do these results apply to the UK wealth tax proposals?

The UK proposals generally tax wealth above £10 million (versus $50 million in the Warren proposal). That brings in a larger share of the affluent population, and a greater fraction of total wealth. The Warren proposal elevated the rate to 6% on wealth over $1bn; most UK proposals do not – the Centre for Public Finances model anticipated that 6% tax, but the Penn Wharton Budget Model present one scenario (with a 2% long-run GDP hit) which has a uniform 2% tax.41

Another significant difference is that the key uncertainty in the impact of wealth taxes is the elasticity – how much the amount of declared wealth responds to the imposition of the tax. The response will be in part by avoidance (such as splitting wealth between family members) in part by movement into hard-to-value asset classes, and in part (and most significantly) by leaving the jurisdiction. Here the US has the considerable advantage over the UK that it imposes tax by citizenship not by residence – so it’s much harder to escape the tax than it would be to escape the UK equivalent (as discussed above).

The UK is also more exposed to any withdrawal of foreign investment – our foreign direct investment (as a % of GDP) is much higher than the US.

Detailed work would be required to balance the material differences here: the broader base of the Warren tax, the higher rate on billionaires, the greater ease of migration out of the UK, and the greater sensitivity of the UK to the withdrawal of foreign investment. All we’d say for now is that it’s reasonable to expect the UK impact of a wealth tax to be the region of the 2% figure that these US studies suggest.

Analyses of a German wealth tax proposal

Fuest, Neumeier, Stimmelmayr and Stöhlker published a detailed computable general equilibrium (CGE) study of a proposal to (re)introduce a German wealth tax42 at 0.8% on household wealth over €2m – a considerably smaller tax than any current UK proposal.

The study found a 5% decline in long-run GDP and 2% fall in employment, equating to several hundred thousand jobs.43 Whilst the tax would raise about €15bn each year, the adverse economic consequences would mean €46bn would be lost from other taxes.

In terms of exposure to migration and ease of exit, we would say the UK is more comparable to Germany than the US (although the UK high net worth population is considerably more international than Germany’s).44

Analysis of impact of French wealth tax

When the French wealth tax was abolished in 201745, the French Prime Minister claimed the tax had prompted 10,000 people with €35bn worth of assets to leave France in the previous 15 years. He gave no source for that, and the effect of the tax is contested.

Back in 2008, economist Eric Pichet concluded that capital flight since the creation of the wealth tax in 1988 had amounted to €200bn, that the tax had caused an annual fiscal shortfall of €7bn, or about twice its revenue. However Pichet’s estimate has been persuasively contested, and evidence since the abolition of the wealth tax suggests any effect was limited. The view of the French tax advisers we spoke to is that the French wealth tax was so prone to avoidance and evasion that it likely had little impact on GDP. We therefore don’t think any lesson can be drawn from the French experience – it’s the “wealthy tax fallacy” – comparing leaky historic wealth taxes to the new “zero exemption” proposals.

The argument that wealth taxes do not impact growth

Some US wealth tax proponents simply assume there will be no taxpayer response to wealth taxes. Zucman’s proposal for an internationally coordinated wealth tax simply asserts that adverse incentive effects are “unlikely to be significant”.46 Zucman and Saez argued that a US wealth tax would not reduce overall savings because US domestic savings would be displaced by foreign savings, which wouldn’t be subject to the wealth tax. As we explain above, we don’t believe a UK wealth tax could work this way, given the avoidance/migration it would enable, and the competitive disadvantage it would give to UK-owned businesses. The UK is a more challenging environment for a wealth tax than the US.

Some papers have analysed historic wealth taxes and concluded there was no impact on savings. However, that is another example of the “wealth tax fallacy” – analysing historic and existing wealth taxes which enable “paper” avoidance or shifting into unlisted shares (and therefore maintain savings)4748, and assuming the same conclusions apply to the new wealth tax proposals where the dominant avoidance is “real”, and actually reduces savings. Other of these papers49 focus on income-restricted retirees and near-retirees, who pay the relatively broad-based historic and existing wealth taxes, but are not a significant proportion of taxpayers under new wealth tax proposals with their high thresholds.

We don’t see any of the research as providing reassurance on the growth impact of a “no exemption” UK wealth tax.

The need for a UK-specific analysis

Given the increasingly high profile of the new UK wealth tax proposals, we would welcome a detailed analysis of their economic effect – on investment, employment, growth, and looking specifically at the impact during economic downturns. As far as we are aware, no such study has been carried out.

The valuation problem

The Wealth Tax Commission contained a detailed analysis of the difficulties caused by valuation, supported by seven background papers addressing separate valuation questions. The Commission ultimately recommended against an annual wealth tax because of these issues.

Some property is easy to value: bank accounts, shares in listed companies, recently-acquired real estate. Applying a wealth tax to such assets is reasonably straightforward – although not without problems. Imagine having a large holding in (for example) Carillion, with the company going bust in-between the valuation point and when the wealth tax falls due. That’s a fundamental problem with the design of a wealth tax that no valuation methodology can fix.

Valuing other property is more challenging – even in principle. A particularly important case is that of private/unlisted companies.

Private companies

For some large private companies there is an obvious listed comparator. For example, Iceland Foods is privately owned, but there are many publicly owned supermarkets – so we can come up with a reasonably objective valuation by using their financial data as a benchmark and conducting a “comparative company analysis” (CCA).50 Even then it’s not straightforward. We should discount the valuation to reflect the fact the company is private, not public – you therefore have no easy way to realise your investment (without a complex M&A process). On the other hand, if you control the company then the valuation should be increased to reflect a “control premium” – you can do what you like with the company. How these factors should be assessed is not straightforward – we are aware of three UK tax disputes over private company valuation which lasted more than ten years.

Some other large private companies have no UK listed peer we can benchmark against – say JCB. Here we value through a “discounted cashflow” (DCF) analysis, looking at the cash the business generates, and how much someone would pay to acquire that stream of cashflows. At this point there are multiple uncertainties. Most importantly: what is the discount rate – i.e. the amount we should discount future cashflows to reflect the delay until we receive them? How will the company’s cashflows change over time?

But hardest of all are the companies with no listed peer and no current cashflows. Take, for example, Wayve – a UK autonomous vehicle and AI startup founded in 2017. It secured $1bn of investment from SoftBank, has a few hundred employees, but likely has little or no current income.

How much is it worth?

Do we say it must be worth at least $1bn, because that’s the implication of the amount that SoftBank invested? Problem is, the company will burn through the $1bn quite quickly, and all that’s left is hope. SoftBank has a history⚠️ of making extravagant investments into businesses that fail. But also a history of making spectacular🔒 investments into businesses that soar. Which is Wayve? A wealth tax has to decide.

It’s even harder at an early stage – take the many recent AI startups🔒.

There are other hard-to-value assets, for example art, cars, furniture, intellectual property and agricultural land.

The consequence of valuation difficulties

The difficulty in valuing private companies and some other asset classes has serious consequences.

First, it creates a loophole. Investors will shift from easily-valued assets into hard-to-value assets. Conversely, they will resist shifting from hard-to-value assets into easily-valued assets – so, for example, the owner of a successful private company may resist an IPO which would facilitate easy valuation. As the Wealth Tax Commission said, “there will necessarily be aspects [to valuation] which are open to gaming”.

Second, it creates administrative cost and complication. Valuing every UK private company and piece of art every year is no small matter. You could value every five years, but that’s hopeless for fast-growing businesses, and both creates an opportunity for gaming the system on the one hand, and potential unfairness on the other (e.g. a company could have become worthless, but you’d be taxed on the basis of the previous high valuation). We agree with Fleischer that taxpayers would have a strong incentive to litigate over valuation disputes (and, conversely, so would HMRC).

All of this creates compliance costs for investors and businesses, and requires significant investment from HMRC (on the Wealth Tax Commission’s figure, over 10% of the £4.3bn total current cost of running HMRC).

A 2019 poll of US economists found a large majority agreeing that a wealth tax would be much more difficult to enforce than existing taxes because of valuation issues. Only 9% disagreed. Valuation difficulties remain a challenge that wealth tax proponents have yet to resolve.51

How other countries manage valuation

It’s these issues that mean all current wealth taxes avoid proper valuations of private companies and (in many cases) other hard-to-value assets:

- The Spanish wealth tax excludes private companies altogether (a notable step given the tax was enacted by a socialist-led coalition government), and has an income-linked cap on wealth tax liability.

- Norway has a specific tax valuation concept, which has been criticised for under-valuing large valuable companies⚠️ (enabling tax avoidance and distorting investment towards such companies). It’s also been criticised for over-valuing startups – here’s entrepreneur Jan Storehaug talking about one of his companies that failed, but still had a large wealth tax valuation. We expect both sets of criticism are correct.

- The Swiss wealth tax deals with these issues for smaller private companies using a simple formula based on net asset value and profitability. That makes valuation very straightforward, but the obvious downside is that it’s easily gamed (with value stripped from a company other than through conventional profits, and debt used to reduce net asset value).

We discuss these wealth taxes in more detail below.

A UK wealth tax could adopt one or more of these approaches, but at the price of greatly reducing revenue and/or creating a substantial loophole that would be exploited. This is the fundamental wealth tax Catch 22: you can have a comprehensive wealth tax with severe valuation problems, or a modest wealth tax that raises much less revenue. You can’t do both.

Wealth tax proponents often minimise valuation difficulties. But the Wealth Tax Commission, after considering valuation issues in significant detail, ultimately recommended against an annual wealth tax.

And the valuation problem exacerbates the liquidity problem…

The liquidity problem

Say you’re the founder of an AI startup. You just struck a deal with a venture capital firm, who paid £10m for a 10% share in your company. At your current “burn rate” of expenses, you think that will last you two years, and you hope that when you get to that point you’ll be able to demonstrate enough success to obtain more funding.

But you now have a company that, on paper, is worth £100m, and you own 90% of it.52 So you have a wealth tax bill of £1.8m.

That’s a big problem. You don’t have £1.8m. You’re living off the VC’s cash injected into the company, and they’re fine with that – but you’re not a millionaire.

So what do you do?

You’ll struggle to borrow the money from a bank at this early stage (unless you mortgage your house; but you probably already have a mortgage, and your house likely isn’t worth £millions).

So you probably have to immediately sell some of your company. This isn’t the company issuing shares; it’s you personally selling some of your 90% stake. In theory you only have to sell 2% of the stake for £1.8m53 – but not many people want only 2% of a startup. And you’re a forced seller – you have to sell, and everyone knows that, so you won’t get a good deal. You may have to sell 5% to get your £1.8m.54

And you have to do this every year.

So you get “diluted”. The founder ends up owning less of their own company, and (most likely) you end up with a splintered share ownership.55 That’s bad for startup formation.

This has been a particular issue in Norway, and the Norwegian Government responded in May this year by proposing that business owners be able to postpone wealth tax payment for up to three years, with interest charged at the rate of (currently) 9.25%. It’s been criticised for being too short a period, and too high a rate. Deferral is also no answer to the problems faced by startups – no founder would defer a wealth tax given the risk that the company fails, leaving them with a large deferred tax bill but no assets.

The Spanish solution is to exempt shares in private companies, provided certain conditions are satisfied, both for the owners and for employees with small shareholdings⚠️. That greatly reduced the tax base, and facilitated avoidance resulting in very limited revenue from the tax. The old French wealth tax took the same approach, with similar results.

The liquidity problem of startup founders is particularly economically significant, but liquidity problems are a more general feature of wealth taxes. The Wealth Tax Commission estimated that a quarter of all taxpayers would face liquidity problems.56

There are plenty of mature businesses that don’t spin off much cash – they would now need to, instead of reinvesting the cash into the business. As we noted above, there is evidence⚠️ that this is a significant effect.

Farmers suffer from land valuations out of all proportion to the cash that their business can generate – there are relatively few farmers with £10m of land, but those few would likely find it very challenging to fund a wealth tax without selling some of their farm (and in due course it’s plausible there would be few privately owned farms over £10m).

In addition to exempting private businesses, the Spanish wealth tax includes a “cap” which means that, if the combined income tax and wealth tax57 tax liability exceed 60% of a person’s income, then the wealth tax is reduced commensurately, up to 80%. That prevents high effective rates, and helps people with liquidity problems, but it also means that some very wealthy people can structure their affairs58 to greatly reduce their liability.59.

The Wealth Tax Commission report included a paper on liquidity which concluded that, at a £5m wealth tax threshold, 98% of those with liquidity issues would be farmers and business owners. It discussed various solutions: loans, caps, transferring part of a business to the Government, but found none to be terribly satisfactory.6061

Bastani and Waldenström‘s review of the literature concluded that there were no easy answers to these problems, and capital gains tax was ultimately a preferable approach to taxing wealth.

Does the tax treat different businesses fairly?

Wealth taxes have complex “horizontal equity” problems that mean people in a similar economic position are treated very differently:

Unfair impact on capital-intensive businesses

The new proposed wealth taxes in principle apply the same way to everybody. But in practice they apply very differently to different types of business. Some example scenarios:

- Paul spent five years growing his tech startup. It hasn’t made a profit, but the latest venture capital funding round values his stake at £18m. Paul usually draws £200k from the business to live off. But the wealth tax values his business on the basis it’s worth £18m – so £160k of wealth tax each year62, plus valuation and compliance costs of £180k to £270k in the first year, and £90k to £135k in subsequent years.63 Paul will be forced to sell shares in his business to fund the tax – with the consequences we set out above.

- Bob spent ten years building up his widget-making business to the point that it now generates £2m of profit each year. The wealth tax uses standard industry multipliers to value his business on the basis it’s worth £18m – so, again, £160k of wealth tax each year, plus valuation and compliance costs of £180k to £270k in the first year, and £90k to £135k in subsequent years.

- Samir spent ten years working as a management consultant and is now a partner in a large firm, making £2m of profit every year. The firm’s value is almost entirely in its human capital64, so he will have little or no wealth tax liability for his ownership of the firm.

The fundamental point here is that the wealth tax taxes capital-intensive businesses more than businesses reliant on human capital (like management consultancies, law firms, and boutique investment banks). The effective rate is highest for startups. This is contrary to the principle of horizontal equity – why should people with identical incomes face wildly different effective tax rates merely because one business needs machinery and the other needs laptops?

And, perhaps more importantly, it will tend to distort investment into less capital‑intensive sectors.

Unfair impact on wealthy people who have paid significant tax

Take these examples:

- Emma is a successful commodities trader at a bank. She spent years working and earning enormous bonuses on which the bank was taxed at the time at 13.8% (employer national insurance)65 and she was taxed at 47% (income tax plus employee national insurance). So a total rate of tax of 53%, after which she now has £20m of savings.66

- Mira is a private equity executive. Her funds have made impressive returns, some of which she received as “carried interest”, taxed (at the time) at 28%, after which she now has £20m of savings.

- Jane inherited £20m from her parents, who gave her their lucrative property development business in their Will when they died. It was entirely exempt from inheritance tax under business relief (before the relief was restricted) and Jane then immediately sold the business to receive £20m cash.

These examples are realistic. Research by Arun Advani and Andy Summers🔒 found a huge amount of variation in the effective tax rates on high earners. A rational policy on taxing wealth might say: Emma has paid a fair amount of tax. Mira has paid too little. Jane has paid much too little. Therefore we should change the way we tax carried interest and inheritance.

The wealth tax, however, applies to all three in the same way. Jane is still under-taxed. Emma likely considers herself over-taxed.

Why the unfairness matters

These “horizontal equity” problems mean that the wealth tax is a poor answer to the question of how to tax the rich more fairly. 67 That’s a problem for people who want a fair tax system. It’s also a problem for Emma – she will likely regard the tax as unjust, and take steps to reduce her liability (both our experience and empirical evidence⚠️ suggests that people are much more likely to seek to avoid a tax they regard as unfair).

A fairer result would be to fix existing taxes on wealth. We discuss this further below.

Don’t existing wealth taxes show that wealth taxes can work?

In 1990 there were twelve wealth taxes in Europe – now there are only three: Spain, Norway and Switzerland.68. The chart at the top of this report shows the decline over time.

It’s important to look at tax systems as a whole. If Spain, Norway and Switzerland didn’t have wealth taxes then generational wealth would be largely untaxed, because none of these countries have material inheritance taxes.69 So if the UK adopted a wealth tax it would be unique in taxing wealth during life and at death.

This suggests we should immediately be cautious about assuming that what works in Switzerland works in the UK. And when we look at the detail of these taxes, we see that they are very different to the wealth tax proposed for the UK:

Spain

On paper, the Spanish wealth tax70 applies at high rates to the very wealthy – 2.21% on assets above €5.3m and 3.5% on assets over €10m. However, the tax followed the fate of most wealth taxes: it pragmatically contained generous exemptions: most importantly, private company holdings are generally exempt. That limited the economic damage, but also facilitated avoidance – the revenue raised by the tax is therefore small.71

As we mentioned above in the liquidity discussion, the Spanish tax also has a “cap” which can reduce the wealth tax by up to 80% if the combined wealth tax and income tax liability exceeds an effective rate of 60%. That eases liquidity problems, but creates an avenue for avoidance.

So, whilst the Tax Justice Network say⚠️ countries can raise $2 trillion by copying the Spanish wealth tax, the Spanish wealth tax only raised €619m in 2023.72 When a wealth tax raises so little revenue (0.04% of GDP), the tax is little more than symbolism – and there is a high risk that taxpayer responses mean that overall it has lost revenue.

Norway

The Norwegian wealth tax applies at 1% on assets above about £140k, with an additional 0.1% above £1.6m.

The Norwegian wealth tax raises about 0.4% of GDP. In UK terms that would mean around £10bn. However the Norwegian wealth tax applies to all assets over £140k, so it’s much broader than the UK proposals; if it only applied to wealth over £10m it would have raised (in UK terms) about £7bn.73

Certain asset types benefit from “discounts“. This, the absence of inheritance tax, and other features of the Norwegian tax system mean that overall the Norwegian tax system is regressive⚠️, and under-taxes the wealthiest 1%.

Nevertheless, between 2021 and 2023, a series of changes meant that Norway more than doubled the effective rate of its wealth tax on the very wealthy – and that has had consequences.

It’s too early to have reliable data on these changes, but the Norwegian newspaper Dagens Naeringsliv reported that 22 wealthy Norwegians left in 2022, in advance of these increases. Further analysis by Kapital, the Norwegian business magazine, found that, out of the wealthiest 400 Norwegian families, 41 relocated in 2022 and 75 in 2023, so that 40% of Norway’s wealth was now owned from abroad – some 780 billion kroner (£57bn) compared to the 32 billion kroner raised by the wealth tax (£2bn).74 This has alarmed the Norwegian tax authority; a consultation was recently launched proposing a new deferral rule to ease the burden on shareholders in illiquid private companies; opinions are mixed on whether it will change anything.

There is a very important difference between the very wealthy in the UK and the very wealthy in Norway. The list of the 400 wealthiest Norwegians is almost entirely a list of Norwegians, born in Norway, and who made their money in Norway. A tenth of the list are salmon farmers. The equivalent UK list is very different. It’s far more international, and many of the list weren’t born in the UK, and made their fortune before coming to the UK. That reflects the nature of the UK, and London in particular – it’s long been a magnet for mobile capital. But that capital remains mobile – many of the most wealthy have only tenuous ties to the UK.

The UK is likely to remain highly international even with the end of the non-dom regime. We should therefore expect that the UK is much more susceptible to wealth tax migration than Norway.

Switzerland

The Swiss wealth tax varies considerably between cantons but, like Norway, it is a broad-based tax, rather than one that only applies to the very wealthy. The wealthiest 1% pay about 60% of the tax.

Despite this, the Swiss wealth tax raises far more than any other wealth tax in the world, past or present: over 1% of Swiss GDP.

How can this be, when Switzerland is usually regarded as a tax haven?

Because the wealthy pay little or nothing in other taxes. Income tax rates are low, and much lower for dividends on privately-held companies. There is no capital gains tax – so with planning, the wealthy can convert income into capital and potentially pay no tax at all on their investment return (as was the case in the UK before 1965). Only a few Swiss cantons impose inheritance tax on bequests to spouse/children.

So some people have described the Swiss wealth tax as a form of minimum taxation for the wealthy – without it, the wealthy would pay little or no tax.

However, the impact of the Swiss wealth tax is limited for many very wealthy people. There is extensive planning. The rate is as low as 0.11% in some cantons, doesn’t apply to foreign investors, some cantons have Spanish-style income-linked caps, and there is a complete exemption for real estate outside Switzerland. Some asset classes are either under-valued or can escape tax altogether. The impact on the Swiss equivalent of non-doms is limited further by the special “lump sum” regime. And Swiss advisers tell us that it’s common for “deals” to be struck between canton tax authorities and very wealthy taxpayers that ensure artificially low valuations of privately held businesses and other hard-to-value assets.

So it’s not a surprise that a recent analysis from Martínez, Marti and Scheuer concluded that the Swiss wealth tax is not particularly progressive (particularly in recent years), but simply a means for the cantons to secure a regular revenue stream.

We believe it’s reasonably clear that most very wealthy people pay significantly less tax in Switzerland than in the UK.

The wealth tax would take years to implement

The usual Budget timetable is sixteen months between a Budget announcement and legislation applying from the start of the next tax year. We’ve never had a wealth tax in the UK, and the size of the Wealth Tax Commission papers is an indication of how much legislation would be required, and how complex that legislation would be.75 The Commission concluded that that an annual wealth tax would be “much more difficult to deliver” than a one-off tax, and that its timeline would “likely be longer”.

Looking at other recent taxes, the digital services tax (a reasonable simple standalone tax) took eighteen months between announcement and implementation, and the sugar tax (more complex than the DST but much less so than a wealth tax) took twenty five months. These taxes have one thing in common: they are paid by a small number of taxpayers (we believe under 20 in each case), and therefore didn’t require a “systems build” – everything could be done manually. The wealth tax is very different, and the ten years it took for HMRC to implement “Making Tax Digital” set a cautionary precedent for the relatively large new reporting base the wealth tax would create. As the Institute for Government has said, complex measures need more time for consultation and HMRC operational input to avoid implementation problems.

Having spoken to retired civil servants and retired HMRC officials, we believe it’s realistic to expect that a complete legislative framework for the wealth tax, including the usual rounds of consultations, would take one year more than the usual timetable.76

At the same time, HMRC would need to create a new administrative apparatus. The Wealth Tax Commission estimated up-front costs of £600m – that’s over 10% of the £4.3bn total current cost of running HMRC.

Tax is paid 31 January after the end of the relevant tax year.77 It follows that, if a wealth tax were announced in the Autumn 2025 Budget and the usual sixteen month timetable was followed, it would first apply in the 2027/28 tax year, with the first revenue from the tax received in January 2029.

However, if – as we expect – the wealth tax legislative process was slower than for normal legislation, the tax would first apply in the 2028/29 tax year, with the first revenue received in January 2030 (i.e. after the next General Election).

What about an internationally coordinated wealth tax?

Many (but not all) of these problems would be eliminated if every country adopted a wealth tax. Cross-border investment decisions wouldn’t be distorted, and billionaires would have nowhere to go.

Gabriel Zucman has proposed an internationally coordinated wealth tax of 2% on wealth over $1bn. The idea is that, if a country (say the US) doesn’t adopt the tax, then other countries would tax US billionaires’ holdings in their own country. There would be no escape. This mirrors the strategy adopted by the OECD in its corporate global minimum tax.

There are, however, two significant problems with this:

First, the four countries with the largest numbers of billionaires are highly unlikely to introduce a wealth tax, or cooperate in the introduction of a wealth tax: the US, China, India and Russia. The proposal therefore, realistically, has no prospect of success.

Second, the OECD corporate global minimum tax has the considerable advantage that Google is not going to respond to the UK introducing a new corporate minimum tax by exiting the UK. Even after the tax, Google is still better off doing business in the UK than not. That’s not true for a wealth tax. If the UK adopts an internationally coordinated wealth tax and the US does not, then the rational response of a US billionaire would simply be to exit their UK investments and replace them with other investments that aren’t subject to a wealth tax. Or indeed, invest indirectly (such as through index funds), which would be very complex and perhaps impossible for countries to trace through.

Isn’t a wealth tax popular?

Opinion polling has shown strong support for a wealth tax, with three-quarters supporting and only 13% opposing. That’s impressive – it’s also unsurprising.

There’s plenty of evidence that, if people are presented with a tax proposal that apparently raises money without downside, then they will indicate they support it.

Portland Communications conducted polling where people were asked which taxes they thought should be increased (without any context on the amounts raised by each tax). The list was dominated by taxes that few people ever pay (at least not directly). On the other hand, when people are asked which taxes they want to cut (without any context about the impact of those cuts), they choose the taxes that they do pay⚠️.

Once a cost is identified then the answer can change significantly. YouGov found that polling support for Brexit (before the referendum) dropped significantly when people were asked to imagine how they’d vote if Brexit made them £100 per year worse off. We undertook polling with WeThink which found that, of those willing to pay more tax to fund the NHS, fewer than 20% were willing to pay more than £100 a year. There is an even broader effect: people presented with a full breakdown of their annual tax liability are more likely to favour tax cuts and spending cuts.

None of this should be a surprise – an analysis by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) found that adding brief contextual information measurably changes answers across political topics. If you include no context, or one-sided context, you are getting answer which doesn’t tell you much about actual public attitudes. Yes Minister mocked this kind of opinion polling forty years ago – it’s a shame that it’s still carried out.78

Politicians who’ve made policy on the back of context-free polling have often gone awry:

- In the 1992 UK general election, the Labour Party proposed raising both income tax and national insurance for people on higher incomes. This polled and focus-grouped well. The public view changed, however, once it became the focus of political attacks during the election campaign, and it become one of the factors later blamed for Labour’s defeat.79

- In the 1993 Australian federal election, opposition leader John Hewson’s Liberal–National Coalition campaigned on a sweeping tax reform, including introducing a 15% Goods and Services Tax to fund other tax cuts. The package polled well; but after political attacks during the campaign, it became blamed for a surprise Labor victory.

- In the 2015 UK general election, Labour proposed a “mansion tax” on homes worth £2m or more. It initially had wide support in polling, but during the election campaign began to be viewed less favourably following hostile press coverage. The policy was abandoned after the election, and Jeremy Corbyn did not reinstate it for the 2017 or 2019 elections.

Our conclusion is that any tax (or spending) policy put in a polling survey, which doesn’t seem to adversely impact the voter directly, and doesn’t mention trade-offs, will poll and focus-group well. That says nothing about either its merits, or how popular it would be in an actual political environment.

The one-off retrospective wealth tax

The Wealth Tax Commission is, we believe, the most serious and comprehensive examination of wealth taxes ever undertaken. It recommended against an annual wealth tax because of the valuation problem discussed above. Instead, it recommended a one-off retrospective wealth tax. The idea was that the Government would enact a 5% wealth tax on all wealth over a threshold, with valuation determined as at a date in the past. The tax would then be collected over five years, at 1% each year.

The critical element is that the valuation was as of a past date, so no action today (migration, moving to other assets etc) would change the result. Avoidance would be impossible. The economic damage of a wealth tax (disincentivising savings and incentivising shifting into hard-to-value assets) would be avoided. Valuation would still be difficult, but it would only have to be done once.

Many people will recoil at the retrospective nature of the tax80 – legal challenges would be inevitable, and the result not predictable.81

Our view is that the retrospective wealth tax is technically a clever solution to the disadvantages of an annual wealth tax. But that is dependent on the tax being both unexpected (before the valuation date) and a one-off – and we don’t believe these conditions could be met in practice:

- The retrospective wealth tax is immune to avoidance only if it is not expected. But could so unusual and unprecedented82 a tax really be implemented, practically and legally83, without a popular mandate? We are doubtful. But a popular mandate means plenty of time for people to respond to the wealth tax by exiting their UK residence or changing asset classes.

- We are also doubtful that a retrospective wealth tax could be introduced suddenly and without any warning. Budget leaks are increasingly common⚠️, and this would be a highly complex and technical measure involving a large number of politicians and civil servants. One answer is to announce the principle of a retrospective tax, with the detail to follow later, but that would create massive uncertainty as well as heightening the prospect of a successful legal challenge.

- A Government could seek to counter people’s expectation of a retrospective wealth tax (and the action they took to avoid it) by making the wealth tax retrospective to a much earlier valuation date, before the tax was expected (and this is what the Wealth Tax Commission proposed). But the further back in time the retrospection runs, the greater the unfairness (given that many people’s wealth would have changed between the valuation date and the date the wealth tax bill comes due). That adds to the risk of a successful legal challenge.

- The retrospective wealth tax’s key economic advantage is that, because it’s a one-off, it doesn’t affect future savings/investment/migration decisions. However that is only true if the tax is credibly viewed as a one-off. The Wealth Tax Commission evidence paper on the economics of tax said this was a “daunting” challenge. We agree. There is a long history of one-off taxes becoming permanent – from UK income tax to the 1977 Spanish wealth tax and the more recent Spanish solidarity tax. We expect many wealth tax supporters would want such a wealth tax to recur, and that a rational taxpayer would expect it to recur.

The context is important: the Wealth Tax Commission were working during the height of the pandemic, and looking for a one-off solution to the fiscal challenges the pandemic had created. It is rare to see anyone advocating this kind of tax today.

The policy alternatives

Dan Neidle was recently interviewed by Times Radio alongside a Green Party MP. Her response to Dan’s criticism of the wealth tax was: “Don’t you care about the rise in inequality?”

This is a bad failure of reasoning. The question is whether the wealth tax works. If it doesn’t work, on its own terms, then its aims are irrelevant.

It is certainly possible to argue for a wealth tax on the basis it reduces inequality, even if it causes economic damage – but that is not an argument wealth tax proponents are making. And we agree with Auerbach and Hassett that a wealth tax is not the best instrument for reducing inequality, and with Hebous, Klemm, Michielse and Buitron that a better solution is to reform existing taxes.

The deficiencies in the wealth tax don’t mean we can’t, or shouldn’t, tax wealth. They mean that any proposal has to be looked at realistically, in particular considering the effective rates the proposal creates, the resulting incentives, and the economic consequences (as well as the practicality of implementation).

The current UK taxation of wealth

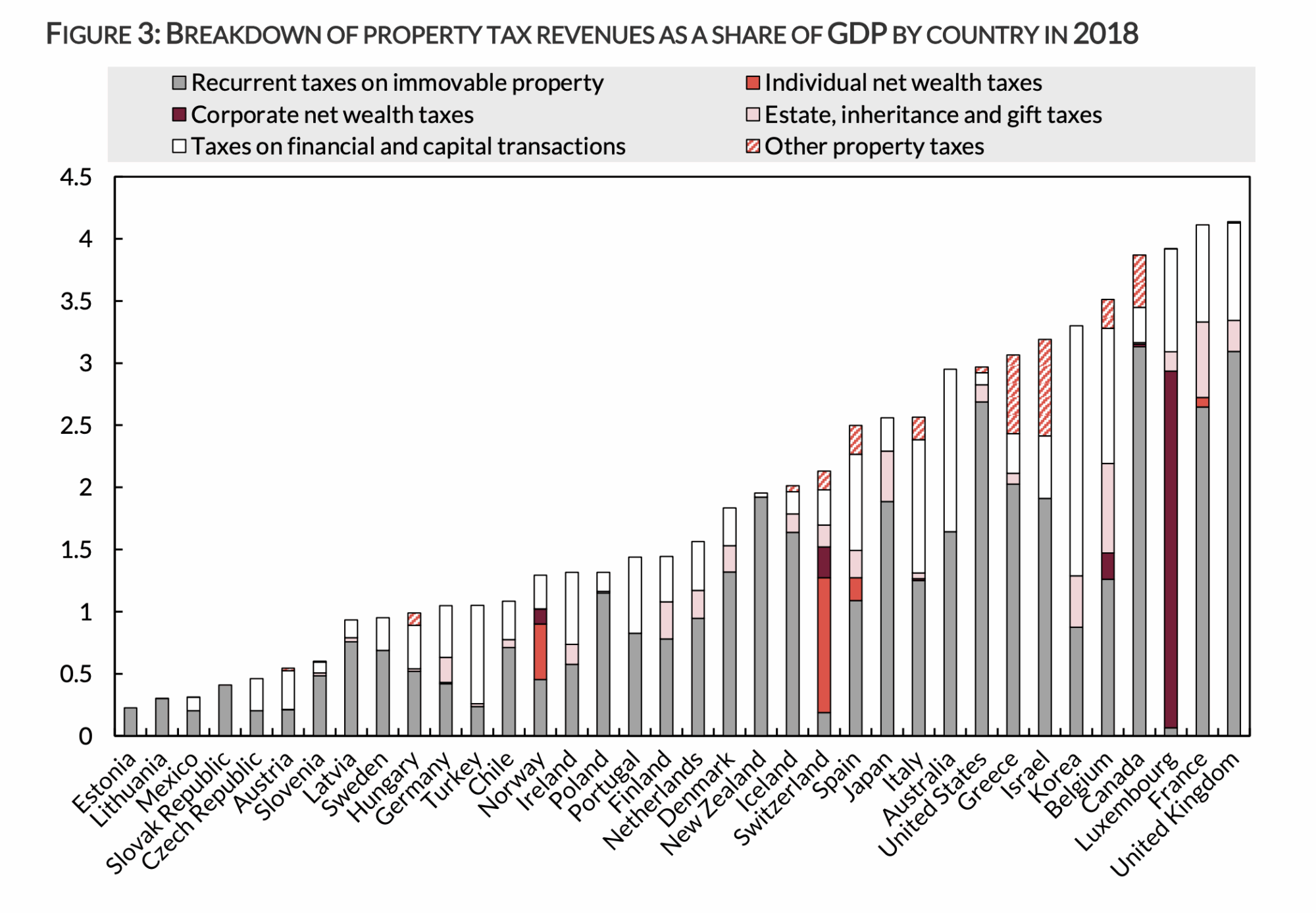

If we look at all taxation of wealth and property, the UK has higher tax as a percentage of GDP than any other OECD country:84

What makes this chart more extraordinary is that the UK has a below average level of overall tax as a percentage of GDP, and much lower than most its immediate neighbours on the right side of the chart.

The reason is simple: council tax (it’s most of that grey bar – a “recurrent tax on immovable property”).

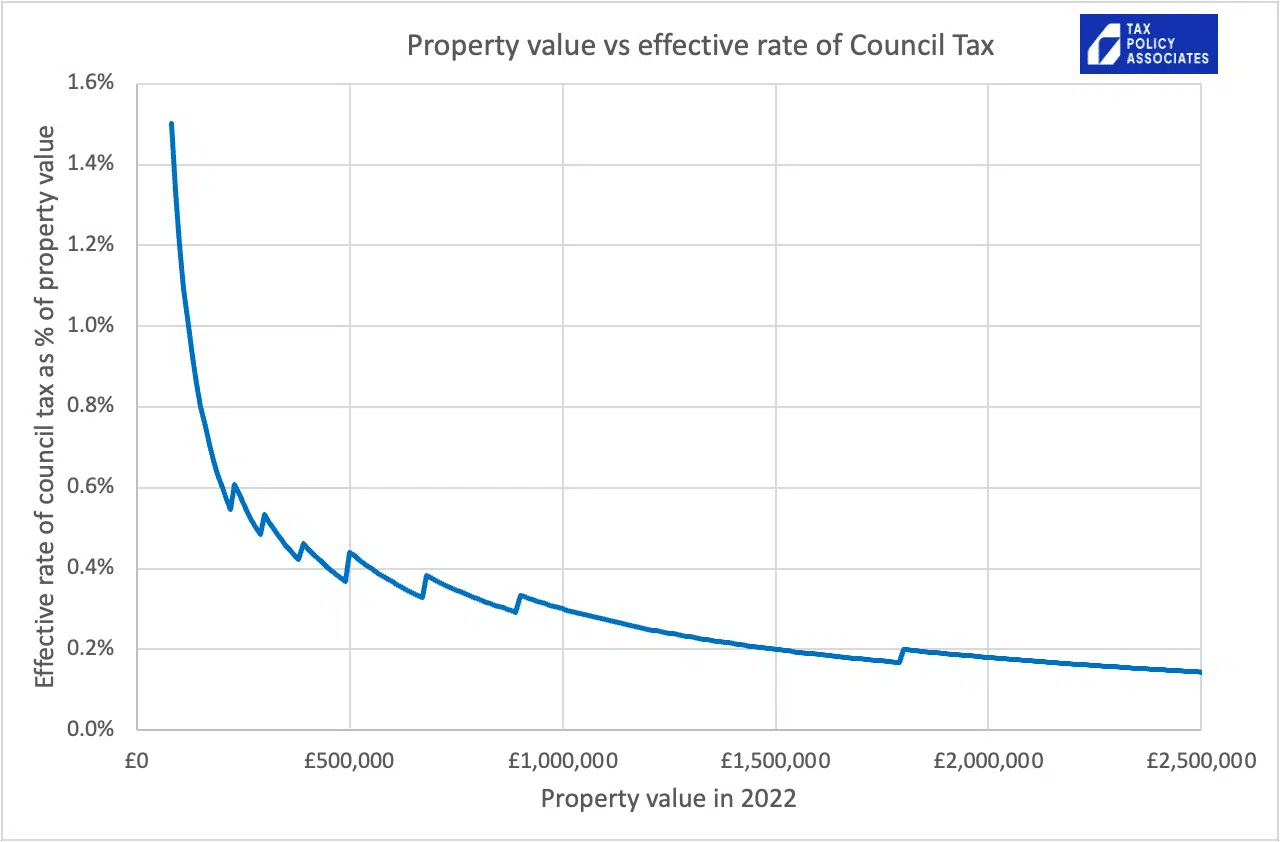

Council tax is a tax on wealth, but a really poorly designed one. A £100m penthouse in Mayfair pays less council tax than a semi in Blackpool. And if we plot council tax liability against property value, it’s clear that the tax that hits lower-value properties the most:

There are serious problems with the UK’s other taxes on wealth and property. Capital gains tax over-taxes actual investment and under-taxes labour income that’s been converted to capital gains. Inheritance tax remains easy to avoid, and (in doing so) distorts investment. Stamp duty land tax (SDLT) discourages property transactions and labour mobility.

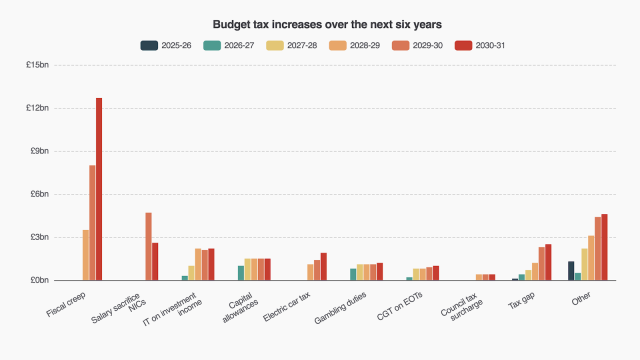

The UK’s taxes on income also fall badly short on both equity and efficiency standpoints. Income tax and national insurance contain taper effects that generate marginal tax rates exceeding 60% on relatively modest incomes, and over 100% in some cases.

It would make much more sense to reform these taxes than to begin a dangerous experiment with wealth taxes. We have written about reforming capital gains tax about inheritance tax. However it’s our view that reforming land taxes should be a priority, in the interest of both fairness and boosting economic growth.

Taxing land effectively would be both more efficient and fairer than taxing all wealth.85

A programme of tax reform isn’t just a technical exercise. It requires political will, cross-party consensus, and public engagement. But, as the Wealth Tax Commission report said, even substantial reforms are likely to be administratively easier than a broad-based annual wealth tax.

Every moment spent dreaming about a wealth tax is a wasted opportunity to reform the system for the better.

Conclusion: high risk, wrong priority

The people who’ve looked most seriously at wealth taxes have concluded they’re not workable.

- Labour’s 1974 manifesto contained a commitment to implement a wealth tax. Denis Healey said⚠️ that “We had committed ourselves to a Wealth Tax: but in five years I found it impossible to draft one which would yield enough revenue to be worth the administrative cost and political hassle”.

- The Mirrlees Review, the most detailed examination of the UK tax system, said the wealth tax was “exactly the wrong policy”.

- The Wealth Tax Commission concluded that the serious problems with valuation meant that an annual wealth tax should not be adopted. As the foreword to the Commission says, “an annual wealth tax is a non-starter in the UK and we should fix our existing taxes on wealth instead”.

- The IFS’s participants in the Wealth Tax Commission have said that “it is difficult to make the case that an annual tax on wealth would be a sensible part of the tax system even in principle”.

- An IMF analysis concluded that a wealth tax would be economically damaging and inequitable, and reform priorities should focus on strengthening the design of capital gains tax and inheritance tax.

- A study of a proposed German wealth tax, similar to that proposed for the UK said the burden of the tax was in reality “practically borne by every citizen”, and it “fails to significantly promote economic equality or create additional fiscal leeway”.

- A report prepared for the Scottish Government considered an annual wealth tax but rejected it, saying “research points to highly negative and distortionary effects on capital accumulation (saving and investment) and residential mobility”.

Wealth tax advocates focus too much on potential revenue and not enough on the economic risks. There are many other tax reforms that would reduce inequality and generate economic growth. The wealth tax gambles with economic growth – and that’s a risk the UK should not take.

Related reading

Some past Tax Policy Associates articles:

- Reforming capital gains tax to raise revenue, lower income tax, reduce the effective rate of CGT for long-term investors but increase the effective rate for people converting labour income into capital.

- Reforming inheritance tax to protect farmers and reduce avoidance, at the same time.

- Reforming property tax, and replacing existing failed taxes with a modern land value tax.

- Ending offshore secrecy, which facilitates tax evasion and avoidance (as well as criminality in general).

- Reforming national insurance, by abolishing it and folding it into income tax.

- The issues around introducing an exit tax to make it harder for people who’ve built up a business in the UK to migrate to a tax haven and escape all tax on their gain.

Thanks to everyone who contributed to this report, particularly the French, German, Swiss, Norwegian and Spanish advisers who provided the benefit of their experience of how the wealth taxes in these countries have operated in practice.

Footnotes

Like Prussia’s Ergänzungssteuer (supplementary tax) of 1893 (often cited as a pioneering example), The Netherlands’ 1892/93 tax, Norway’s introduction of a wealth tax in 1892, Sweden’s 1911 tax, or Denmark’s 1903 tax. The rates were typically a fraction of a percent and (0.05% for the Ergänzungssteuer, and 0.125% for the Dutch tax), and there were wide exemptions. See Chapter 12 of this IFS paper⚠️ or this OECD report, or this wonderful history of the Nordic/Scandinavian taxes. Some of these taxes survived, in a very modified form, as second wave wealth taxes. There were earlier taxes very close to a wealth tax – see this fascinating article about a Jewish quasi-wealth tax in 15th century Germany and Austria. ↩︎

Including France, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, and, briefly, Ireland. ↩︎

The additional OECD country with a wealth tax is Colombia. The way it was implemented has created a rich source of data, but the very different economic environment in Colombia means that we won’t discuss the Colombian tax in this report. Many Muslim countries implement Zakat, a voluntary 2.5% wealth tax. In Saudi Arabia, Zakat is a legal obligation, although we understand that enforcement is highly inconsistent and in practice it is semi-voluntary. We don’t, therefore, regard Zakat as relevant to modern wealth taxes. ↩︎

Unite previously called for a one-off wealth tax, but appears to have changed policy. No further details are available on their methodology. ↩︎

We don’t understand how so high rates raise so little money. The TUC refers to research from Landman Economics which isn’t published, and therefore we cannot assess. The owner/director of Landman Economics separately called for a wealth tax of 2% on wealth over £2m, which he said would raise £46bn. We don’t know where these numbers come from. In the same article, he said that “According to HMRC statistics, abolishing just 40 reliefs and allowances that serve no good purpose other than tax avoidance would result in a gain of just under £74 billion.” This claim is false, and is not supported by any statistics from HMRC or anywhere else we are aware of. ↩︎

No methodology is published. ↩︎

The Telegraph has reported that🔒 our founder, Dan Neidle, was a co-author of the Wealth Tax Commission report. This is not correct – Dan had no involvement in the writing of the report, but was asked to provide some comments on an “in-specie” payment proposal considered as part of the valuation section of the report. Dan said he thought that specific proposal wasn’t viable, and he doesn’t agree with the report’s conclusions (which recommend a “one-off” wealth tax). The Telegraph appears to have confused acknowledgments with authorship. ↩︎

8% is the figure most often used to represent long-term stock-market returns, although it has been criticised as simplistic and based on 1970s expectations in a high inflation environment. Over the very long term, the return from US stocks after inflation has been 7%. Recent US returns have been much higher. There is fascinating data on investor returns in this FCA paper on the figures that FCA-regulated firms must use when promoting investments. We will use 8% simply because it is a reasonably standard and accepted approach. ↩︎

These calculations are simplified. A proper analysis of the marginal effective tax rate (METR) should also take deductibility rules into account, as well as inflation (given its effect on capital taxation). Adding that complexity would not change the point that the wealth tax greatly increases the effective rate of taxation; it would however illustrate that the METR of the wealth tax is higher in a high inflation environment than a low inflation environment. See pages 59 et seq of this OECD paper. See also para 2.2 of Scheuer and Slemrod ↩︎

i.e. because 2% is 25% of 8%; and 25% plus 39.35% = 64.35%. ↩︎

i.e. because, at a corporation tax rate of 25%, £100 of post-tax profit means the pre-tax profit was £133. ↩︎

From page 61 of this report. The report is interesting for its sympathy to the wealth tax concept. It concludes that wealth taxes could have a role in countries with low capital income taxation and/or no inheritance tax, or countries experiencing high wealth inequality. However it recommended that any wealth tax must have an exemption for business assets, cutting against the thrust of the new wealth taxes. ↩︎

The lower figure comes from a paper on administrative costs written by David Burgherr, a PhD student in economics. It concludes compliance costs would be between 0.05% and 0.3% of taxable wealth, with a central estimate of 0.1% of “taxable wealth”, implying c£1bn of taxpayer compliance costs. Whilst some of the details of Burgherr’s approach can be criticised, we feel the central estimate is a plausible number. ↩︎