Today’s episode⚠️ of Untaxing is about Jaffa cakes and VAT.

With the benefit of hindsight, that’s a very small VAT issue on a day when VAT has become a very large geopolitical issue.

Donald Trump is considering applying tariffs to much of the world because of VAT. He believes it’s a tariff. You’ll be unsurprised to hear that I disagree. But the details of why he’s wrong are interesting, and go beyond “all UK buyers pay VAT so there’s no discrimination”.

So, whilst there are many good articles explaining why VAT isn’t a tariff, I’ve written one with more detail, more footnotes, some beer, a theorem from 1936, and a callback to Jaffa Cakes.

What is a tariff?

A tariff is a type of tax which applies to imported goods but not locally-produced goods. That’s the World Trade Organisation definition (and tariffs are very much its thing) as well as the approach followed by the OECD in its own research.

Most countries impose tariffs on a variety of imports, usually with a complex series of rules (“schedules“) setting out which tariff applies to which goods.

So, for example, the UK imposes a 10% duty1 on importing most types of car. A car showroom buying cars from a British car manufacturer doesn’t pay this; a car showroom buying from a foreign manufacturer does. This is a tariff.

What isn’t a tariff?

Tariffs are sometimes called “duties”. That’s confusing, because not all duties are tariffs.

Take beer duty.

The UK imposes a £21.78 duty on each litre of alcohol contained in beer. Beer brewed in the UK to be sold in the UK is subject to the duty at the point it is produced. Beer brewed outside the UK is subject to duty when it’s imported.

Another feature: if beer is brewed in the UK to be exported then it’s generally not taxed.

This kind of tax is often called “destination-based”, because whether the duty applies depends entirely on where the consumer is, and not on where the producer is. Most countries in Europe and beyond also have destination-based alcohol duties.2

Another example of a destination-based tax is the various US State3 sales taxes. These generally apply to sales of goods and services to consumers in the State, whether the seller itself is in the State or outside it; they don’t apply to in-State sellers exporting to another country. 4

A destination-based tax is not a tariff, because it applies to both locally-produced and imported goods. There are (necessarily) different collection mechanisms for foreign and domestic sellers, but the overall tax result is broadly the same.

Why is VAT different?

VAT, in principle, is just another destination-based tax like beer duty or New York State sales tax. It’s charged where the ultimate consumer is in the UK, and not charged where the ultimate consumer is outside the UK. The location of the seller is irrelevant.

But the administrative detail of how VAT works is very different.

Sales taxes apply once and once only, to the final sale to the consumer. A business selling a car to someone living in New York has to charge State and local sales taxes. The rest of the supply chain – the suppliers of the raw materials, the car manufacturer, etc – is unaffected by the tax.

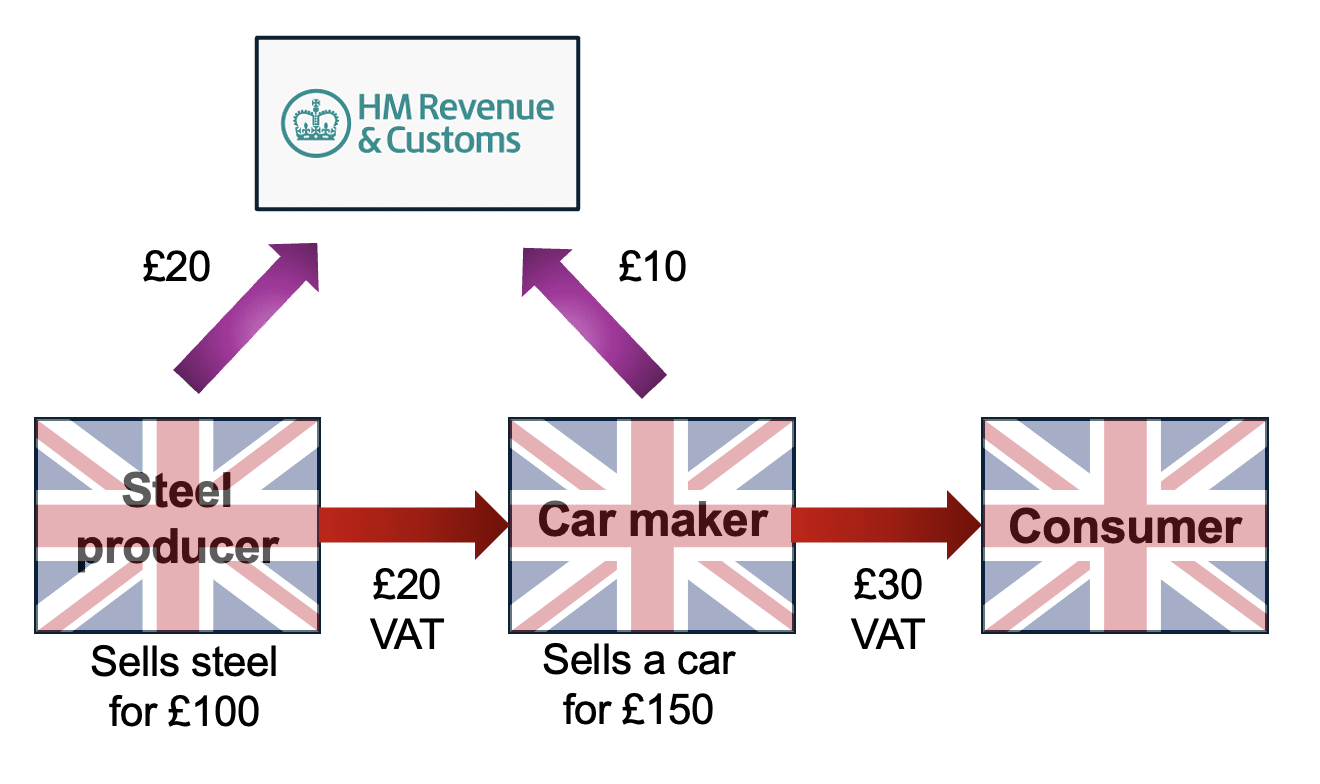

VAT applies at every level of the supply chain – to the “value added” at that level. To take a simplified example:

So:

- When the producer sells the steel for £100, it has to charge 20% VAT – so it charges the car manufacturer £100 plus £20 VAT, and accounts for the £20 to HMRC.

- When the car maker sells the car for £150 it also has to charge 20% VAT, so the consumer pays £180. The car maker recover the “input” VAT of £20 it paid to the steel producer, so it accounts to HMRC for £10 – i.e. £30 minus £20.

- The overall VAT paid is £30 – just as if this was a simple 20% sales tax only paid by the car maker. But it’s collected at each step in the supply chain.

- Of course in reality there will be hundreds or thousands of businesses in the supply chain, each collecting a small amount of that final £30 of VAT.

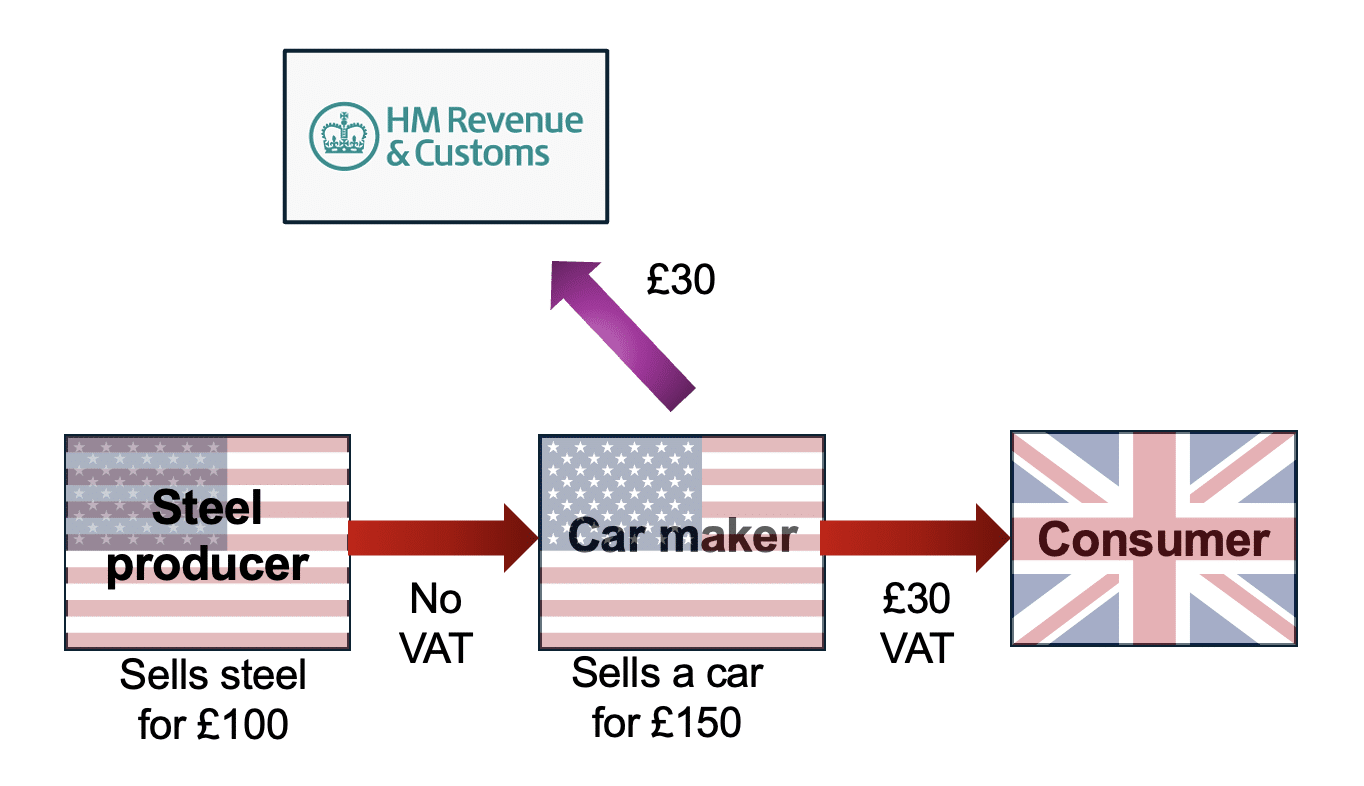

And here’s the result if it’s a US business selling to a UK consumer:

There is of course no VAT when the US steel producer supplies the steel to the US car maker. The only charge is “import VAT” when the car maker imports into the UK. The result, however, is the same: £30 of VAT.

I’ve used the UK in these examples, but the result would be the same across the EU (as UK VAT remains almost identical to EU VAT). It’s also the same in most – and possibly all- the other countries that apply a VAT or GST.5

Why is VAT so complicated?

Why does VAT work this way, when the ultimate result is the same as a simple 20% sales tax? Wouldn’t it be simpler to just work like a US State sales tax, and collect that 20% all in one go at the final sale?

There is only one reason why VAT works this way: tax evasion.

- The “final sale” can be a tricky concept to apply. If I’m buying a car, I can easily claim I’m a business, and so (illegally) escape sales tax. The seller has limited ability or incentive to check my bona fides. VAT doesn’t have that problem, because a seller charges VAT to everyone. A consumer can’t recover VAT; other people can. We can therefore expect much higher rates of tax evasion under a sales tax than a VAT.6

- You can try to limit the “false business” problem by putting stringent rules on sellers; but then you can have the opposite problem, with sales tax being applied when it shouldn’t be. You’d then have a “cascade” of sales tax hits instead of just one. That would be economically damaging.

- VAT collects from everybody. No need to work out if you’re selling to a business or a consumer.7

- And another big advantage: if almost everyone in the supply chain is filing VAT returns then it’s often easy for a tax authority to spot the ones who aren’t. VAT creates its own audit trail.

- And if all of this fails, and only one person in the supply chain fails to pay VAT, then it’s only their value-add which goes untaxed.

It’s therefore received wisdom amongst tax economists that US-style sales taxes are only viable up to a certain percentage of the sale. Beyond that, and to the levels that European economics require to fund their spending, sales taxes would be widely evaded and/or would be economically damaging. And even at the US levels, VAT would be preferable.

Why does Trump think VAT is a tariff?

One possibility is that he doesn’t understand that a domestic producer selling into the UK faces the same VAT as a US producer.

Another possibility is that he misunderstands how VAT is credited when UK businesses are exporting.8

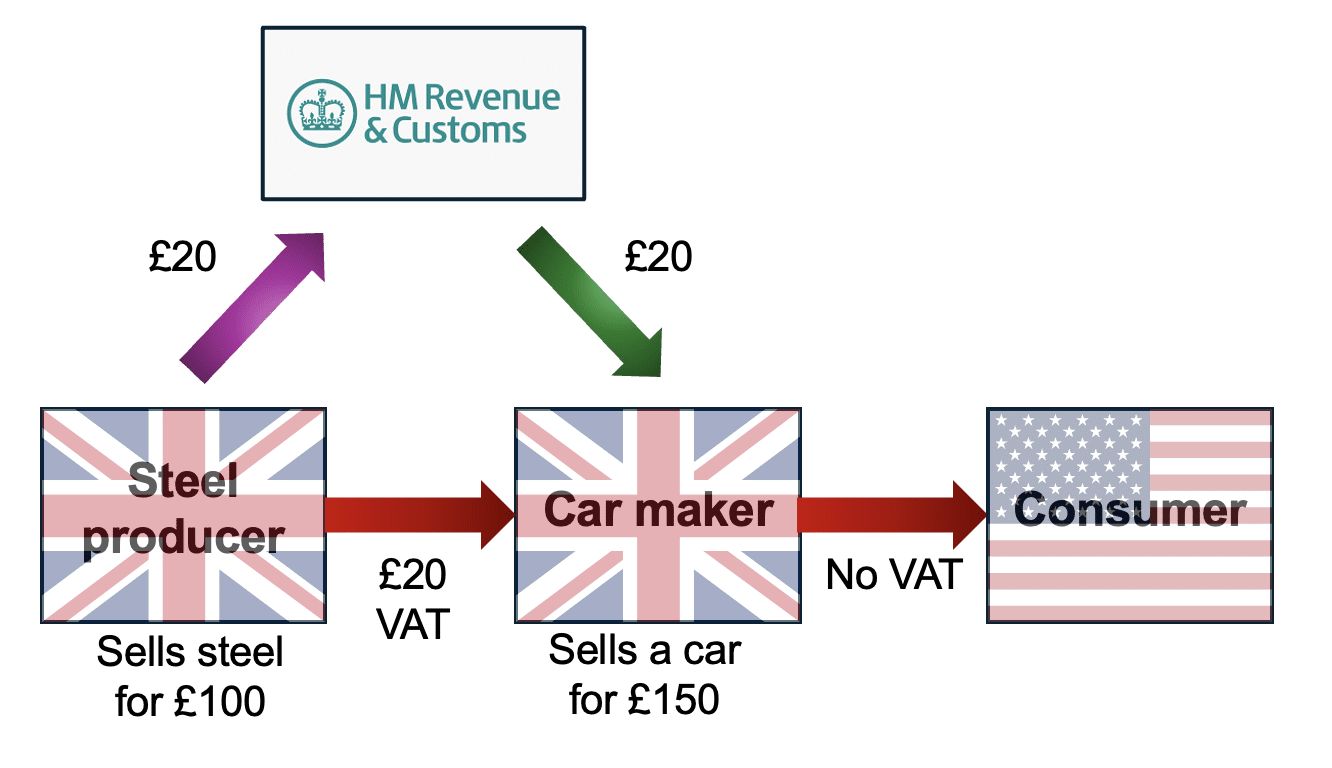

Here’s how it works:

The car maker has charged no VAT on its sale to the final consumer, because he or she is outside the UK. But there has still been £20 VAT collected in the supply chain. That’s the wrong result – and the answer is that the car maker can “recover” the £20 in the same way it did in the first example above.

Since it’s a sale to a US consumer, in some US states there would be sales tax on the final sale. It’s unaffected by the supply chain.

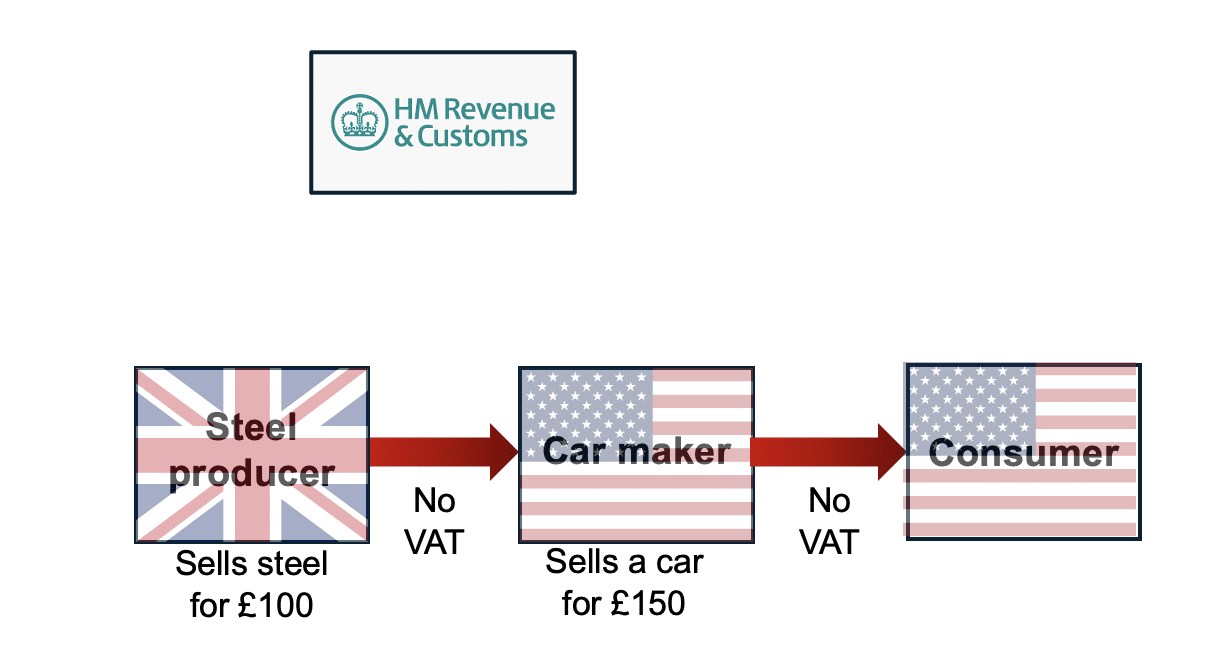

On the surface this looks like a subsidy of some kind for exports, but it really isn’t. The net result is exactly the same if it was a US car maker buying (hypothetically) British steel and selling to a US consumer:

There is no difference between the two cases.

Again, since it’s a sale to a US consumer, in some US states there would be sales tax on the final sale.

Does VAT encourage exports?

One more sophisticated argument sometimes made is that VAT is distortive because it encourages UK companies to export to non-VAT destinations (a kind of reverse export-subsidy).

There is a tax policy wonk response to this and an economist’s response to this.

The tax wonk answer is that this might be the case if the cost of VAT was borne by sellers, but when VAT is introduced (or increased), the price is added onto goods. It’s consumers who pay.9 So a seller will usually make the same profit selling into a VAT country than into a non-VAT country; and any small effects that may exist are swamped by other factors (shipping costs, marketing costs, tariffs, regulation, non-tariff barriers, contractual issues etc).

The economist’s argument is much more subtle, and concludes that VAT actually reduces exports.

Paul Krugman makes the point compellingly in this widely-cited⚠️ paper. There are two separate effects, pushing in opposite directions.

First:

- Countries that adopt VAT have less income tax and corporate tax than they would otherwise have.

- VAT applies to most imports but not exports. Income tax and corporate tax apply to domestic production and exports, but (mostly) not imports.

- So higher income/corporate tax advantages imports and disadvantages exports.

- By instead having a VAT, countries like the UK are (relatively speaking) disadvantaging imports and advantaging exports.10

But a second effect goes in the opposite direction:

- The “policy wonk” position above assumes VAT applies to all products. In practice, it doesn’t.

- Major areas of expenditure aren’t subject to VAT – that means Jaffa Cakes and (somewhat more significantly) housing. So people will tend to spend more on housing and Jaffa Cakes (and other exempt and zero-rated items) and less on VATable goods and services.

- Housing is obviously not imported (nor are Jaffa Cakes). So VAT tends to reduce imports, as we buy more domestically-produced goods.

- Now the bit non-economists find counter-intuitive. The Lerner symmetry theorem (from this 1936 paper🔒 by Abba Lerner11, a foundational element⚠️ in trade theory) says that, if imports are reduced, then exports are also reduced. The reason is that if we buy fewer foreign products, then foreign businesses are receiving less GBP from British importers.12 Since the world has less GBP, the value of GBP will rise, and the world will buy fewer UK products. UK exports therefore fall.13

The Krugman paper contains a rigorous analysis of both effects, and concludes that the second is stronger. Hence VAT in the real world discourages exports and imports. This is another reason why we’d all be richer if VAT applied to a wider range of products – like Jaffa Cakes⚠️.

VAT, once more, behaves nothing like a tariff.

Doesn’t VAT fund the NHS, which effectively subsidises companies?

The argument goes like this: VAT raises £170bn, which is very close to the cost of funding the NHS. In the US, with no Government funded national healthcare system, most of the cost of healthcare is paid by businesses. The fact UK businesses don’t have this cost gives them a significant advantage. Therefore the NHS, and the UK tax system generally, amounts to an export subsidy.14

The argument is, however, wrong. The US does have national funded healthcare systems (Medicare, Medicaid, and Military and VA Programs) and, whilst they don’t provide the same breadth of coverage as the NHS, they cost US taxpayers almost exactly the same (as a percent of GDP) as the NHS.

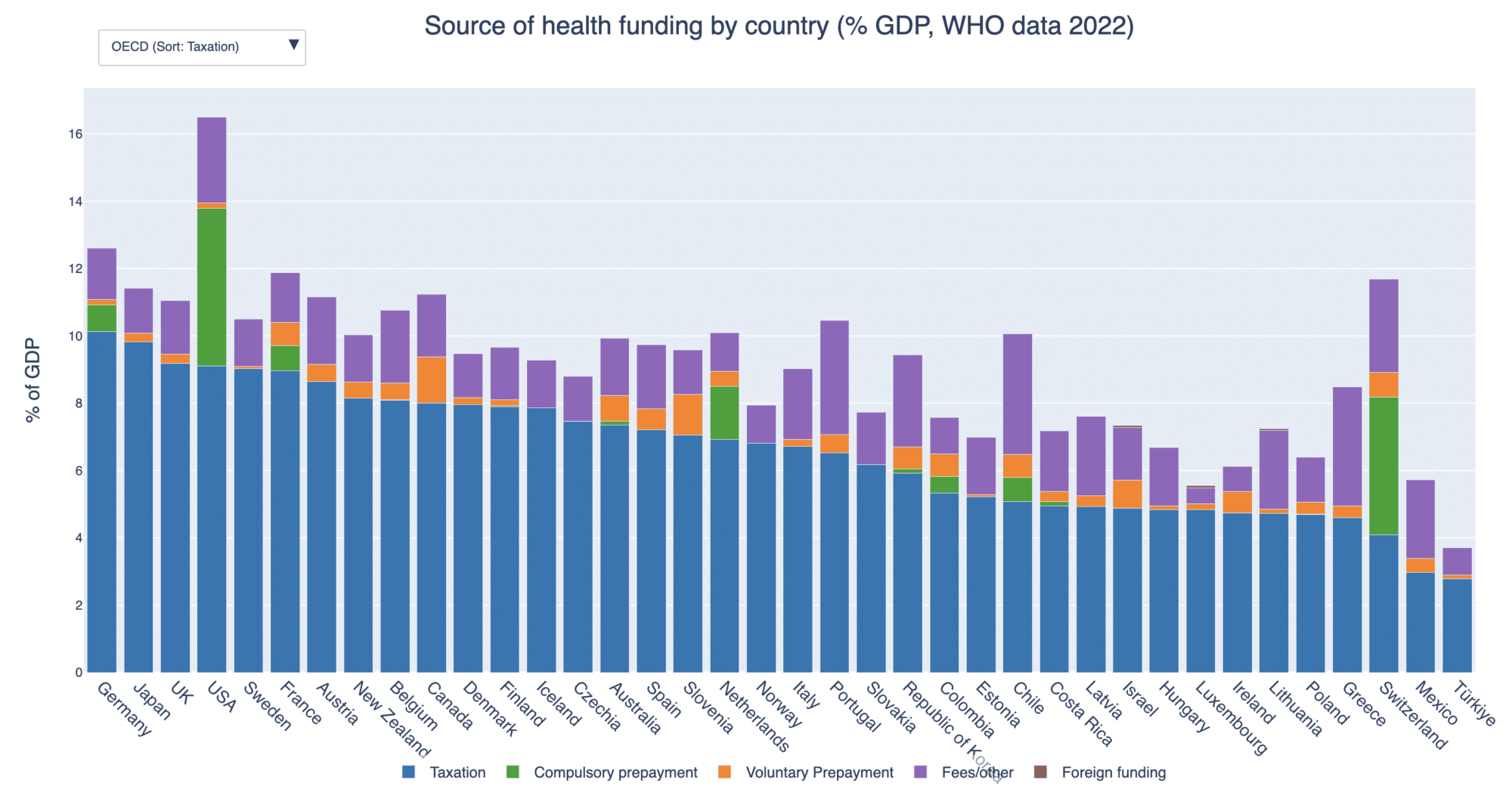

We can chart this using WHO data:

The blue bar is healthcare funded by taxation, and the UK and US (third and fourth from the left) figures are almost identical. The source for this is the World Health Organisation’s Global Health Expenditure Database.

So whilst it’s true that US companies bear much larger healthcare insurance costs than UK companies, the reason is not that the UK Government is subsidising healthcare more. The actual reasons are discussed here.

There’s an interactive version of the chart here, which lets you look at all countries (not just the OECD) and sort by total spending, as well as tax-funded spending. The “all country” chart has rather a large number countries, so to view country names you need to either zoom in or hover over a bar (and you’ll see the country name displayed).

There is an informative ONS article comparing UK healthcare spending with other countries.

The code that created the chart is available on our GitHub.

More technical arguments

There are a couple of more technical niggles.

The first is that paying import VAT is a hassle in a way that normal VAT isn’t. It’s a “non-tariff barrier”. This was a real concern during the Brexit discussions, particularly the three month delay in recovering input VAT. That led to a system of “postponed VAT accounting” which means that the cashflow cost of recovering input VAT becomes equivalent to the cost of recovering normal domestic VAT. There remain some bureaucratic annoyances with input VAT (and in countries like Italy and Spain they can be quite serious), but it’s just a small part of the overall “trade friction” – the hassle of importing goods.

Another argument goes as follows: VAT is applied to tariffs. Therefore if a US manufacturer sells a car to a UK consumer there’s a 10% tariff, and then 20% import VAT on top of that. Total VAT on the price plus the tariffs of 22%15. But a UK manufacturer selling to a UK consumer faces no tariffs – total VAT plus tariffs of 20%. Discrimination!

But on close inspection this doesn’t make much sense:

- Almost no US car manufacturer sells direct to a UK consumer. They’d sell to a UK distributor, and the distributor will recover its VAT – including the import VAT on the tariff. The same is true for most goods (and services aren’t subject to tariffs). So, in practice, non-refundable VAT applying to a tariff is a rarely seen complication.

- But even in theory, it’s not VAT that’s the problem here. VAT makes the effective rate of tariffs higher, like it makes everything higher. The problem is the tariff, not the VAT.

The United States is an outlier

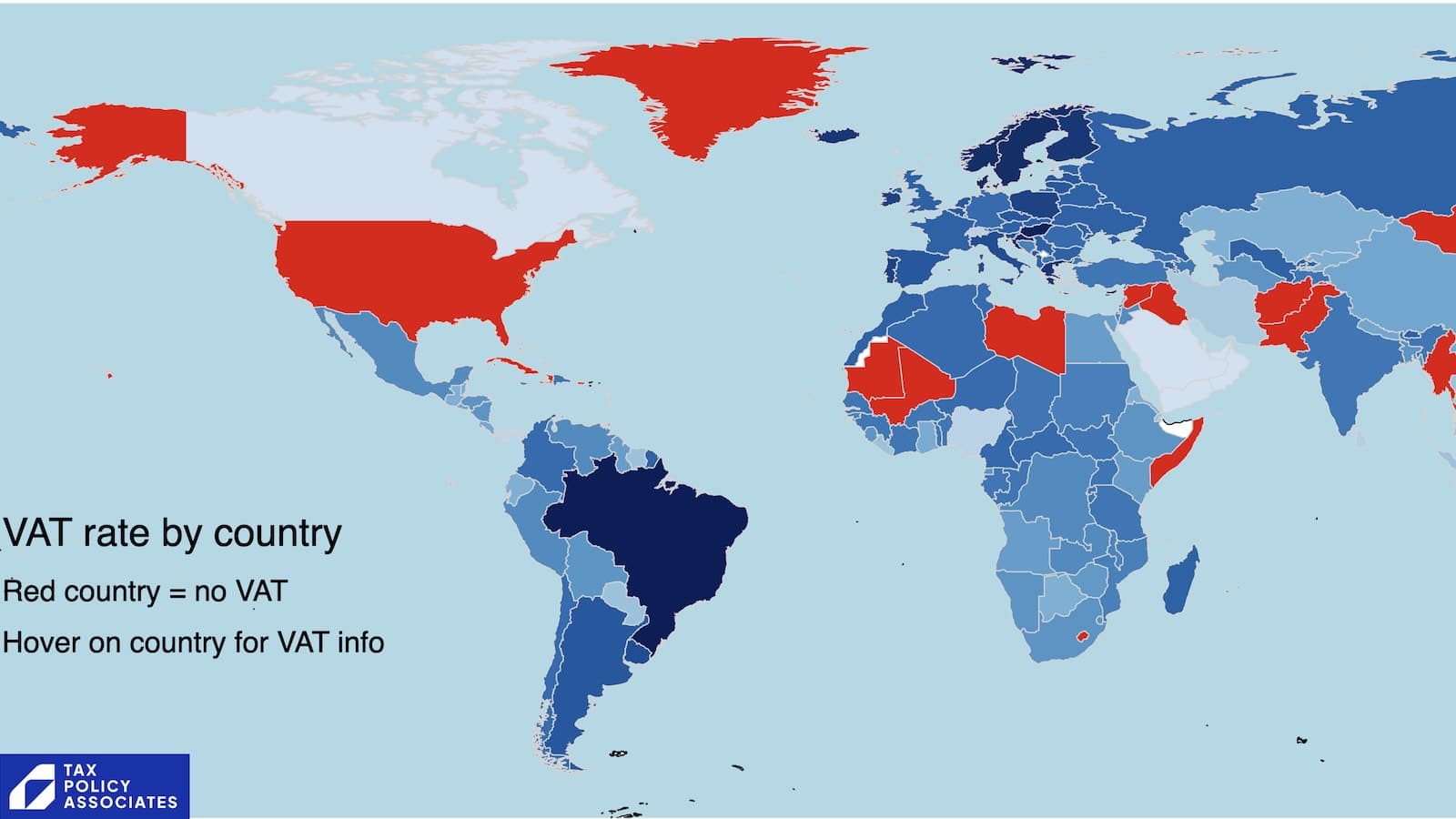

Every large developed country, and most other countries, have adopted a VAT (full screen version here):16

The most recent convert was Brazil, which had a mess of national and local sales taxes. It finally adopted VAT in 2023.

That leaves just Hong Kong, Pakistan, a few small islands and tax havens… and the United States.

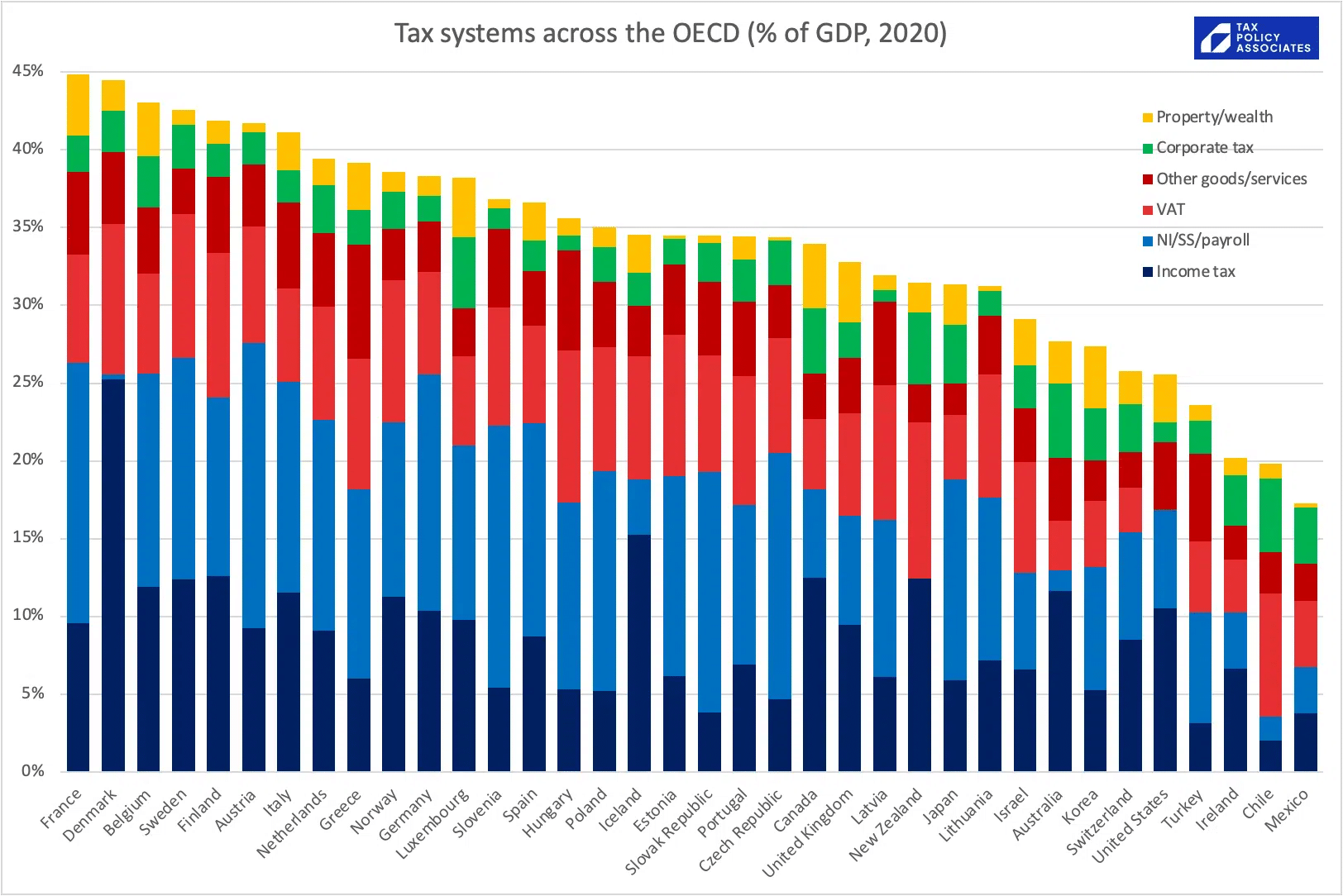

It’s often said the US is a lower tax country than the UK. That is true – and much of the difference is down to VAT:1718

There are two consequences from this.

First, no major economy could abandon VAT, as Trump seems to wish, and maintain its current level of spending. Income taxes would rise to unsustainable levels (in the UK, we’d pay, on average about 60% more income tax).

More entertainingly, it follows from Krugman’s paper that if the US kept the overall level of tax the same, but substituted VAT for some personal tax and corporate tax, and applied VAT to absolutely everything, then that would enhance the competitiveness of, and tend to increase, US exports.

I’m sure Mr Trump is working on this proposal as we speak.

Thanks to everyone whose questions online and offline sparked this article. Thanks to P and Z for their helpful discussions on trade policy and tariffs, K for VAT input, L for US State sales tax expertise, and C for an illuminating exchange on trade theory.

People occasionally ask why most of our contributors are thanked by initials, not names. It’s because they almost all work for barristers’ chambers, law firms, accounting firms or are retired HMRC officials. Whilst we’d never ask them to break any confidences, employers usually restrict public statements from their employees, and both employer and employee would sometimes be concerned about liability. So most (but not all) of our contributors choose an initial – not necessarily their actual initial.

If you have specialist tax, legal or economic expertise and would like to join our very informal panel of experts, do please get in touch.

Footnotes

The UK’s tariff website is a triumph of usability. The EU’s is awful, forcing you to read through a badly scanned capitalised page to work out the code for any particular good. ↩︎

The broad principle in all the different taxes/duties is the same, but the details are very different. That makes life complicated for an international beer company – dealing with all the different rules makes it much harder and more expensive for them to export beer than to sell domestically. But these rules aren’t tariffs. This kind of complexity is inevitable as long as different countries have different tax rules. ↩︎

Often there are one or more additional levels of local sales taxes, sometimes applying on top of the State sales tax, sometimes applying to services that aren’t subject to State sales tax, and sometimes vice versa. ↩︎

Note that, whilst all US State sales taxes are destination-based when it comes to exports to outside the US, the position is more complex for sales from one State to another. Most US State taxes are pure “destination-based” taxes, meaning that (for example) New York State doesn’t impose sales tax on a sale by a New York business to a Texan consumer. Others, like Texas, are “origin-based”, meaning that they apply on sales by a Texan business to a New York consumer – but even origin-based sales taxes don’t apply to goods exported outside the US. ↩︎

A “goods and services tax” is just another name for a VAT; I’d love to know why Australia and other countries thought it would be a good idea to create a different name for what in essence is the same tax. ↩︎

There is, however, frustratingly little evidence of the actual rate of evasion of state sales taxes, and the 5-16% figures sometimes referred to appear to be little more than informed guesses. ↩︎

That’s not quite right, but a good approximation. ↩︎

Another, shared by two US trade lawyer friends, is that Trump just loves tariffs and has no interest whatsoever in VAT. It’s a handy ex post facto justification for something he always wanted to do. ↩︎

The converse doesn’t follow; consumers won’t always benefit⚠️ from VAT cuts, particularly on individual products. ↩︎

I hesitate to disagree with a Nobel laureate, but I am not convinced by this. For the reasons discussed above, VAT is actually a cost for the consumer. But let’s assume I’m dead wrong here, or missing something, and Krugman is right. ↩︎

Ironically, Lerner was a socialist, albeit a member of a now-endangered species: a market socialist. ↩︎

This also works if the goods are bought in foreign currency. The UK importer swaps GBP into that currency, and the counterparty will (often) be swapping it within someone who needs GBP, e.g. to buy British products. GBP is still leaving the country, through a more circuitous route, and reduced imports again means people outside the UK have less GBP. ↩︎

For this and other reasons, tariffs reduce exports as well as imports. ↩︎

The same broad claim is sometimes used to make another argument: that the UK and European economies can afford their national healthcare systems because their defence spending is so much smaller than US defence spending. ↩︎

i.e. 20% of £110. ↩︎

Source for the data is this table from the IMF. ↩︎

State sales tax is on the chart; it’s the dark red bar. ↩︎

Incidentally, don’t be tempted to compare the blue bars (personal tax on income) and conclude that the US level of personal taxation is about the same as the UK’s. Many US businesses, particularly small businesses, are “S Corps” – meaning that they don’t pay tax; instead, their owners pay tax as if they received the income themselves. So US corporate tax revenue appears less than it “should” be (if we could add in S Corps), and US personal income taxes appear more than they should be (if we could deduct S Corp income). A common mistake is to look at the figures for US corporate tax receipts and marvel at the low level of corporate taxation. There’s certainly truth in the proposition that US corporate tax is low, but the figures can’t be eyeballed like that. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Unknown Cancel reply