Despite the Government’s stated commitment to growth, the Budget included no pro-growth tax reform, and its largest revenue raising measure is likely to reduce private sector employment and wages.

The Budget continued a sad trend of tax policy driven by realpolitik rather than long term strategic thinking. It’s to be hoped we see something more substantive in future Labour Budgets.

The need for tax reform

Some of the worst features of the UK tax system are the product of short term political expediency:

- The numerous high marginal income tax rates, often approaching 60% and sometimes over 100%, deter people at the £60k and £100k earning thresholds from working more hours. These rates are a product of “gimmicks” introduced into the tax system to raise more tax without incurring the political pain of increasing headline tax rates.

- Council tax is based on 1991 valuations. A £100m penthouse in Mayfair pays less council tax than a semi in Skegness. The unfairness and inefficiency of council tax is a consequence of a post-poll tax political fear of touching local government taxation.

- Stamp duty land tax reduces labour mobility, results in inefficient use of land, and plausibly holds back economic growth. There is a consensus amongst economists of Left and Right that an annual tax on land value would be fairer and more efficient. But there is a political fear of creating losers (and we are currently seeing how loud the complaints of a relatively small number of people can be, if they believe they’ve lost out from a tax change).

- The rate of capital gains tax is too low, enabling owners of private businesses to convert what is realistically labour income (which should be taxed at 45%) into capital gains (recently taxed at 20%; now rising to 24%). But the rate of capital gains tax is also too high, taxing investors on paper gains even if in real terms they have lost money. Both problems could be fixed at the same time, but that requires taking on vocal interest groups.

- The UK has the highest VAT threshold in the developed world. It deters small businesses from growing, and creates a competitive advantage for people who cheat.1 HM Treasury certainly understand the problem, and many across the political spectrum agree that the threshold needs to come down. However politicians are reluctant to act, in large part because of a reluctance to take on the small business lobby (which in my experience doesn’t represent its members, many of whom are frustrated by the competitive distortions created by the current high VAT threshold).

- The UK has extensive VAT exemptions and special rates – more so than any other country with a VAT/GST system. They’re regressive and result in uncertainty and avoidance. We could restrict the special rates and raise significant revenue and/or cut the rate of VAT from 20%. But no politician feels able to explain this.

- The UK has one of the highest rates of inheritance tax in the world, but collects comparatively little tax. Why? Because of the many exemptions (or, if you like, “loopholes”) which make tax planning IHT away very easy for the wealthy and well-advised. Perhaps for these reasons, it’s a very unpopular tax. The answer: scrap the exemptions and cut the rate. The complaints of the few who lose out would be drowned by the applause of those who gain. Or go for more ambitious reform still, and replace the tax with something entirely different (capital gains at death, perhaps).

- The spiralling complexity in the tax system, and the fact that so few of the Office for Tax Simplification’s recommendations were implemented, is a product of a political failure to make tax simplification a priority. The state of corporation tax, in particular, is making the UK increasing uncompetitive, even compared to countries with significantly higher corporate tax rates than the UK.

And last but not least:

- Employer national insurance mean that we tax employment income much more than self employment income or investment income. That is economically damaging, and creates a huge amount of complexity, uncertainty, and tax avoidance and evasion. The tax has been irresistible to governments who want to raise tax on income in a way which is not very visible to most of the public. We should abolish employer national insurance (but working out exactly how is a very difficult problem).

All of these problems, and many more, create a real need for tax reform. A Government committed to improving the UK’s poor recent growth record should be looking at tax reform very seriously indeed.

The tax reforms in the Budget

There were no tax reform measures in the Budget.2 Nor was there any tax simplification.3

All we saw were revenue-raising measures. That’s an important function of the tax system, but a Budget shouldn’t just be about raising tax.

The need for revenue-raising

Let’s look at the largest revenue raising-measure in the Budget, and the options that were available. I’ll proceed on the basis that the Government had to raise £10bn from somewhere, and ask what the most rational way to do that would be.4

What principles should have driven the decision as to which tax to raise? Particularly when it was a Labour government making that decision, and a Government which had said it was committed to growth?

Presumably something like:

- The tax increase should be disproportionately borne by people who are most able to pay it (the “broadest shoulders“).

- The tax increase shouldn’t have a negative effect on economic growth, for example by creating incentives on businesses to reduce employment.5

- The tax increase shouldn’t be distortive – i.e. create incentives to do things that are artificial and/or would make no sense if it wasn’t for the tax increase.

The simplest tax increase consistent with these principles would be to raise income tax – the Government could have raised about £10bn by increasing the rate of income tax by 1%.6 Those on very low incomes would have paid little or no additional tax (because income tax only starts at £12,570). The impact would have been greatest on those earning higher incomes. Employees, investors, landlords, pensioners – all would have shared the pain of the tax increase.

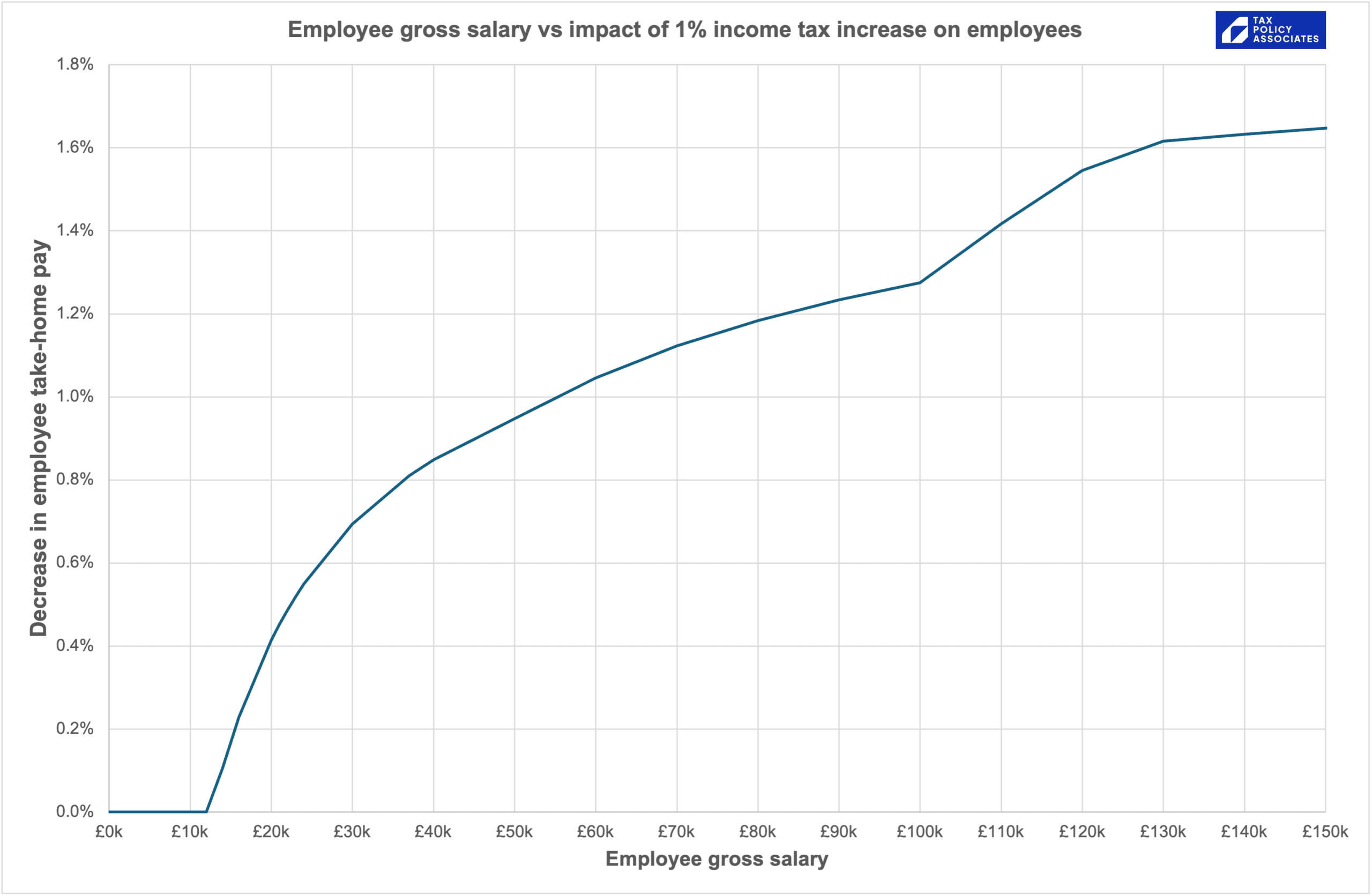

Here’s a chart of the percentage reduction to employee take-home pay that would follow from a 1% income tax rise:78

Someone on minimum wage would see a reduction in after-tax pay of about 0.5%; someone on the median wage of about £37k the figure would see a reduction of 0.8%; for someone earning £150k the figure would be 1.65%. I’d think this would be the kind of gently progressive outcome that a Labour Government would be looking for from a tax increase.

Or if that was too politically tricky, there were plenty of alternatives, albeit more complicated. The Government could have reformed capital gains tax, or made numerous small changes to taxes that mostly impacted the wealthy, but wouldn’t reduce their incentive to invest in the UK.

The revenue-raising in the Budget

Labour instead chose to raise £10bn by increasing employer’s national insurance.

This fails all three tests above:

- Employer’s national insurance applies only to employment, and not to self employment or investment income. Many of those with the highest incomes are unaffected.

- For the same reason, employer’s national insurance creates distortions, and a powerful incentive to hire people as contractors rather than employees. There is a huge volume of anti-avoidance legislation that tries to prevent this, but when the lure is as great as a 15% saving, people will and do continue to try to avoid it. The OBR projects a £500m loss in tax from this.

- Employer’s national insurance is a tax on employment, and it’s axiomatic that if you tax something you get less of it.

The way Labour implemented the national insurance increase made it worse. There were two changes to employer’s national insurance in the Budget:

- the rate went up from 13.8% to 15%.

- The secondary national insurance threshold (from which the 15% rate applies) was cut from £9,100 to £5,000.

The cut in the threshold disproportionately impacts employers with mostly low-paid staff.

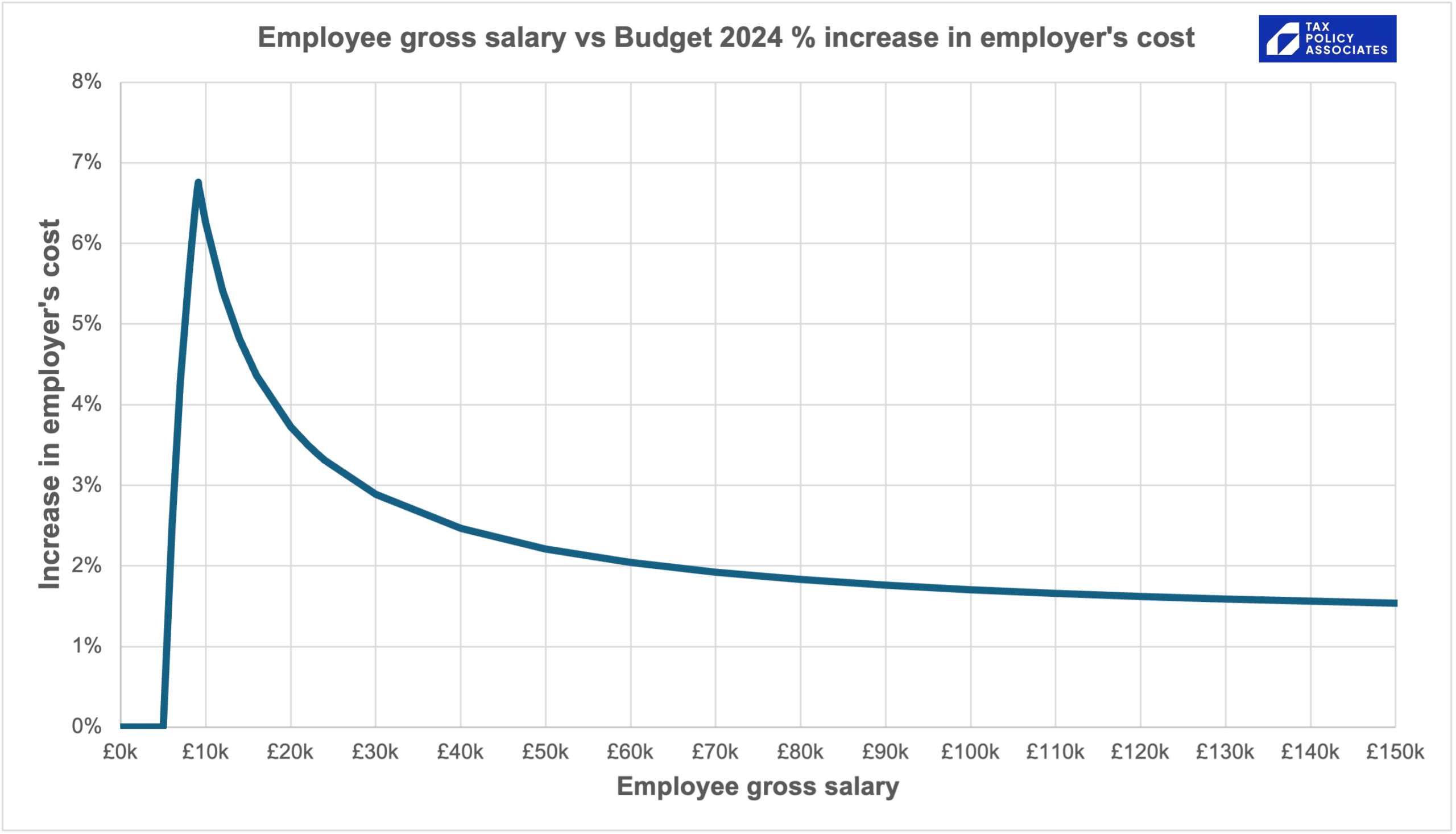

We can illustrate this by charting different wages levels against the increase in the total cost of employing someone at that wage.910

That spike is for those earning around the current £9,100 employer national insurance threshold – the cost of employing someone in this position goes up by almost 7%.11 The cost of employing a full time worker on minimum wage goes up by 3.5%; for a worker on the £37k median wage, the cost goes up by 2.5%. But the cost of employing someone on £150k goes up by only 1.5%.

Why should the Labour Party care if the cost of employing someone on low wages rises?

Because all the evidence shows that the economic impact falls on the employees, not the employer.

The evidence

There is extensive evidence that 60% to 80% of the economic cost of employer national insurance (and similar taxes) is borne by employees in the form of reduced wages. The rest of the cost is shared between reduced employment (again impacting employees, or people who don’t get to become employees), increased prices and reduced corporate profits. I set out some of the research on these effects here.

It’s important to note that this doesn’t mean that an increase in employer’s national insurance causes wages to be cut and people to be sacked. It means that businesses increase wages less than they otherwise would, take on new employees on low wages less than they otherwise would, and/or take on fewer employees.12

The Office for Budget Responsibility agree that most of the burden of the tax increase falls on employees. Here’s their assessment of the Budget:13

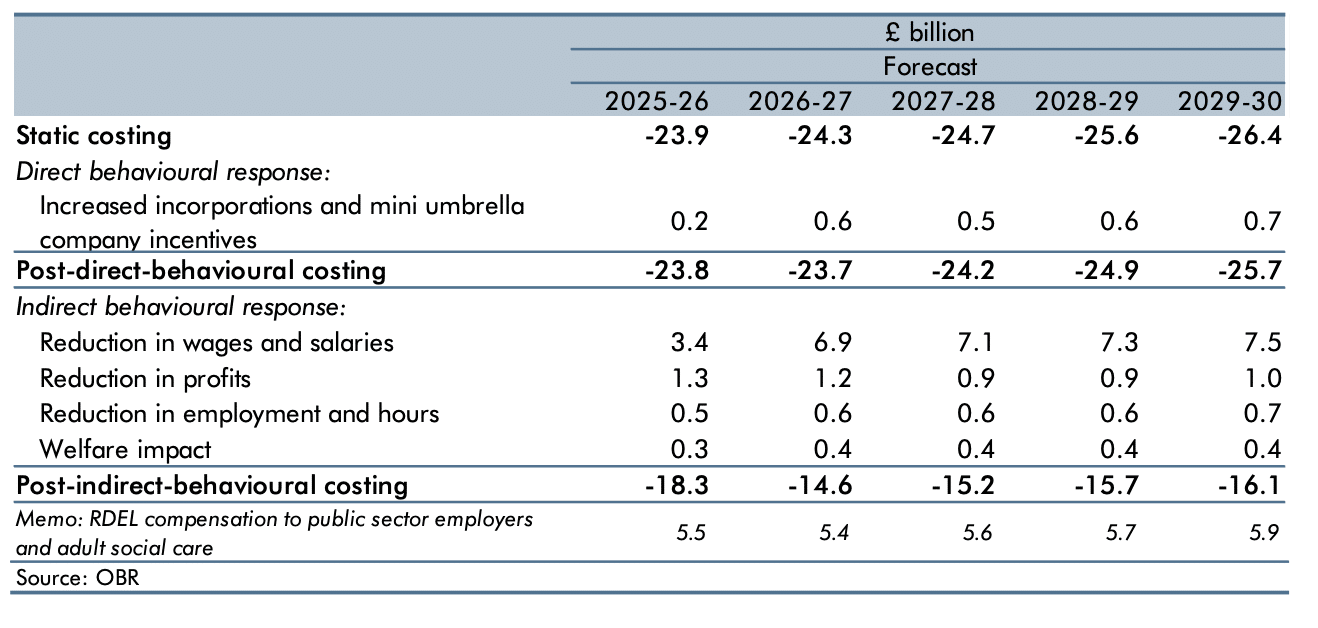

If we look at the 2027/28 figures, the “static analysis” of the employer’s national insurance increase shows it creating £24.7bn of revenue. “Static” means this is a simple multiplication of current employer national insurance revenues to reflect the increased rate.

The OBR then corrects the static figure to reflect behavioural changes. They project a loss in tax from reduced wages and reduced employment of £7.7bn, and a loss in tax from reduced corporate profits of £600m. Reversing-out these figures suggests that the OBR believes over 85% of the £24bn raised by the employer national insurance increase is coming from reduced wages and lost employment.14

And note the £5.6bn figure at the bottom – the cost to the Government and adult social care providers of covering the employer national insurance increase. This has two consequences. First, the £24bn static estimate of the revenue yield in fact ends up as under £10bn – it’s a remarkably inefficient tax increase. Second, whilst we can expect the private sector to mostly pass the cost of the tax increase to employees, the public sector mostly won’t.15

What’s happening in practice?

Most of the research suggests it takes a year or more for increases in employer national insurance to be passed-through to employees. However things seem to be moving faster than that. In the last week I’ve spoken to:

- A board member of a UK financial services business which had planned to increase wages by 5% for 2025; the increase will now be 3%. They will also be moving some jobs from the UK to Eastern Europe (“near-shoring”).

- The CEO of a large retailer that had planned to increase wages by 4% for 2025; the increase will now be 2%.

- A board member of a manufacturing company that had planned to increase wages by 5%; the increase will now be 2.5%.

- The CFO of a large services business which will now be “near-shoring” hundreds of jobs to Eastern Europe.

- A restaurant owner who has cancelled a plan to expand to a new site.

- A farmer who will be cutting the hourly wage he offers to seasonal farmworkers this coming Spring.

- The owner of a small business who had planned to take on a trainee; she now won’t be.

- The owner of a shop who had been planning to expand out-of-season hours, but now won’t be.

All of which suggests that the cost of the employer national insurance increase will be passed onto staff as soon as January 2025. Which is four months before the increase takes effect.

This is a much faster transfer of the cost of the tax increase to employees than I expected.16

The overall picture

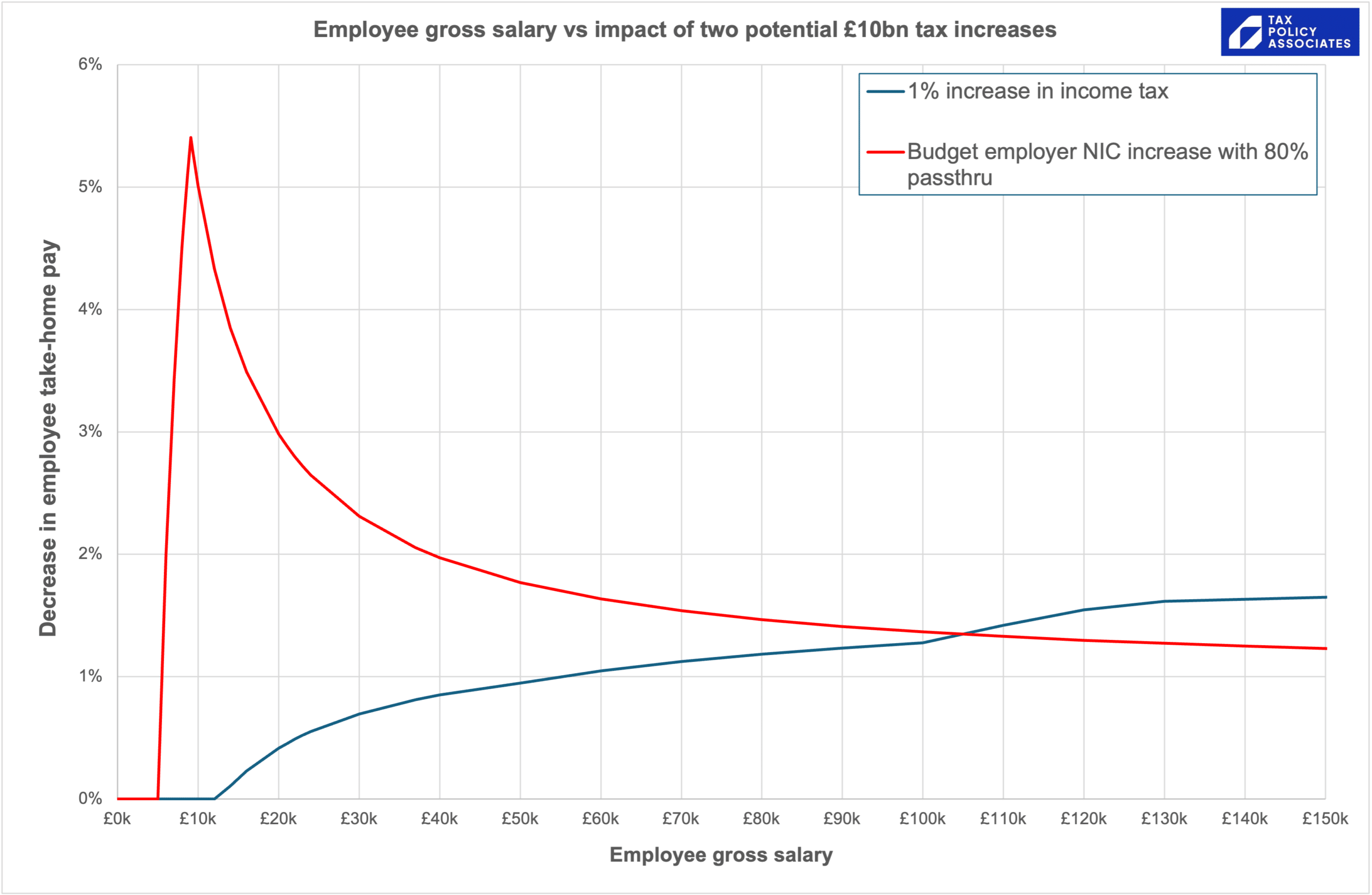

Let’s assume 80% of the cost of the employer national insurance is 80% passed-through to private sector employees in the form of reduced wages. How does the reduction in their take-home pay compare with the effect of my hypothetical 1% income tax increase?

Everyone earning less than £100k from employment income is better off with an income tax increase.

How can this be? How can a 1p income tax increase raise the same revenue as a 1.2p employer national insurance increase, but have so much smaller an effect on most people?

Because of the people not shown on this chart. The self employed, pensioners, partners in professional firms, investors, landlords… they’ll see no impact from the Budget employer national insurance changes, for the simple reason that they’re not employed. But they all pay income tax, and would very much see an impact from a 1p income tax increase.

So why did Labour end up imposing a regressive tax increase?

Two weeks before the Budget, I wrote that increasing employer’s national insurance was one of the worst possible tax increases. I didn’t think it was likely, but added a footnote that I was not very good at political prediction. That footnote was correct.

The point remains: increasing employer’s national insurance as proposed in the Budget is worse in almost every respect than increasing income tax. It’s less progressive and more likely to reduce growth (because it reduces employment). So why do it?

The obvious answer is: politics.

Over the last two weeks, I’ve bemoaned the increase in employers national insurance to various people more politically astute than I am. Their response is that Labour had no choice. During the election campaign, Labour had to rule out increasing most taxes, or it would have risked losing the election. Employer national insurance was all that was left, and so it was employer national insurance that had to go up.

On this version, bad tax policy was the price of election victory. If that’s right, it’s a pretty depressing conclusion.

Why was there no tax reform in the Budget?

One explanation is simply: there was no time. Whilst Labour had done some thinking in Opposition, the lack of technical resources available to an Opposition (particularly after the loss of seats in 2019) meant that the real work preparing detailed tax policy proposals had to start after Labour moved into Government on 5 July 2024, and Ministers got their feet properly under the desk in mid-July. With the Budget on 30 October 2024, that appears to give plenty of time – but the OBR has to be given 7-9 weeks’ notice of Budget proposals.17 So the deadline for finalising Labour’s proposals was early September. Then add the effect of August, and civil service holidays, and Labour really only had a few weeks to come up with the Budget. Expecting Labour to prepare detailed tax reform proposals in that time was unrealistic.

I don’t really buy this. It’s hard to see there will ever be a better opportunity for tax reform than the first Budget of a new Government elected with a large majority. The Budget could have been later. Or there could have been a quick Budget implementing manifesto commitments, with a further “fiscal event” in March containing more detailed measures that weren’t in the manifesto. That’s exactly what we saw in 1997.

The other explanation is that Starmer and his team were too cautious to go near tax reform. If so, they may the reaction to the modest tax changes that were contained in the Budget may make them more cautious still.

My hope is that I am again completely wrong, and that we do see pro-growth tax reform in the next Budget.

Photo by Vicky Yu on Unsplash.

Footnotes

e.g. by splitting one business into several different companies. The rules don’t permit that, and it will often amount to (criminal) tax fraud – but it’s often hard for people to spot. ↩︎

A more generous person than me might classify the changes to agricultural property relief and business property relief as tax reform. But I don’t think that would be right – the changes are a partial restriction of existing reliefs rather than actual reform, and they feel more symbolic than substantive (and also could be better structured; I’ll be writing more about that soon). ↩︎

And a particularly generous person might say that the potential partial abolition of the UK-UK transfer pricing rules is “tax simplification”. But the details make it doubtful there will be much real effect, and in any cases the proposal was originally announced by the previous Government. ↩︎

It could certainly be argued that the Government should have cut spending instead (at least in real terms), but that was never a very likely route for a newly elected Labour Government. ↩︎

It is often said that all tax has a negative effect on economic growth. This is not correct – it depends both on the nature of the tax, and what the Government does with the revenue raised by the tax. This article from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research is an excellent discussion of both sides of this point. ↩︎

The Liberal Democrats for many years had a policy of increasing income tax by 1p to pay for additional education spending. At one point the Conservative Party carried out polling which showed that most people misunderstood this to mean actually paying one penny more tax, not a 1% increase in the rate, This sounds incredible, but I’ve heard the story first hand. ↩︎

For simplicity, this only shows part of the picture, because there would also have been an impact on pensioners and investors on high incomes. Both groups would have suffered a slightly higher decrease in take-home pay, because they don’t pay national insurance and so income tax changes have a slightly greater proportionate effect on them. ↩︎

The spreadsheet with the calculations generating this chart can be found here. ↩︎

The “total cost” here is the gross salary plus employer’s national insurance; I’m disregarding the apprenticeship levy in the chart because that only affects larger firms; it will very slightly reduce the % change. There will often be other costs, e.g. office space, pension, administration – these vary considerably between employers and so can’t realistically be included in the chart. ↩︎

The minimum wage for a worker over 21 works out at an annual income of about £23,000 if they are working full time for the whole year. However some people working part time and/or for only part of the year can earn much less than that. ↩︎

Higher paid workers are more likely to see a reduction in pay increases; lower paid workers a reduction in employment. We may see a particularly strong impact on low paid employment, given the relatively high level of the UK minimum wage. i.e. because wages cannot be reduced for many lower paid workers without either breaking the law (if they are at the minimum wage) or squeezing differentials (for those just above the minimum wage. ↩︎

From page 55 of this document. ↩︎

My working for this: the mean annual wage (as opposed to the median) is about £37,000. Employer national insurance on that is about £5,500 and employee tax is about £6,800 – so tax on the average wage is 33%. The £7.1bn figure therefore implies a reduction in gross wages of about £21bn; the £0.6bn figure implies a further loss of £1.8bn of gross wages through reduction in employment. The OBR also projects a loss in tax from a reduction in profits of £0.9bn. Profits are subject to corporation tax at 20-25% and (in a different form) VAT; all implying a drop in profits of somewhere around £2-4bn. Hence over 85% of the overall hit is borne by employees in the form of reduced/lost wages, and only around 15% by employers in the form of reduced profit. These are back-of-the-envelope estimates so we shouldn’t be surprised that the figures total £28bn rather than £24bn – the overall picture is reasonably clear. ↩︎

Although that’s not necessarily the case in the long term. Public sector pay is impacted by private sector pay, both informally and (in many cases) formally given that that one of the key pieces of evidence considered by the Pay Review Bodies is the level of private sector pay. Hence public sector pay may well end up affected, in which case the RDEL compensation may prove too high, and the NICs increase may end up netting more than expected. ↩︎

When I first saw the OBR figures I was surprised they were showing such a high percentage of the employer’s national insurance increase being passed to employees so quickly. I had assumed (from the research on previous similar tax changes) that this would take several years to work through, and in the meantime the costs would be borne by shareholders (through lower profits) and customers (in higher prices). These conversations suggest that the OBR may be correct, and the incidence transfers to employees much faster than most of the historic research suggests (and possibly more complete). I don’t know why this is. ↩︎

See page five of this document, second paragraph. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Dan Cancel reply