This Government was elected on a platform of kickstarting economic growth. It has a large majority, and four or five years until the next election. It’s a rare chance for real pro-growth tax reform. That’s all the more necessary if we are going to see tax rises.

We’ll be presenting a series of tax reform proposals over the coming weeks. This is the first: how to reform corporation tax.

Most of the tax changes we hear about, in Budget speeches or newspaper columns, are driven by necessity or politics. But there’s more to tax policy than tax hikes or tax cuts, which garner headlines out of all proportion to their actual financial significance in the context of a £2.5 trillion economy. Much more important is tax reform – revenue-neutral changes that would drive economic growth.

Tax reform can do that by lowering the marginal tax rate on work (for example, cutting employee national insurance) or investment (for example, more effective investment reliefs).

But tax reform can also boost growth by reducing economic anti-growth distortions in the current tax system. There are all too many of those – for example, the way that stamp duty deters people from moving house in search of better opportunities elsewhere.

Between now and the Budget we’ll be publishing a series of articles on tax reforms we believe are badly needed. This is the first: corporation tax. You can see the complete set here

All of our proposals could be revenue-neutral, or raise or cut tax, depending on how they were implemented. But revenues aren’t the point: the idea is to make the tax system drive growth (or, at least, not hold it back).

These pieces are very much summaries rather than full proposals – each proposal links to more detailed analysis elsewhere.

The most complete guide to the wider issues around UK tax reform remains the Mirrlees Review – written in 2010, but still highly relevant today. It’s available for free here.

The problem with UK corporation tax

All taxes have two components: the rate, and the thing the rate is applied to – the base.

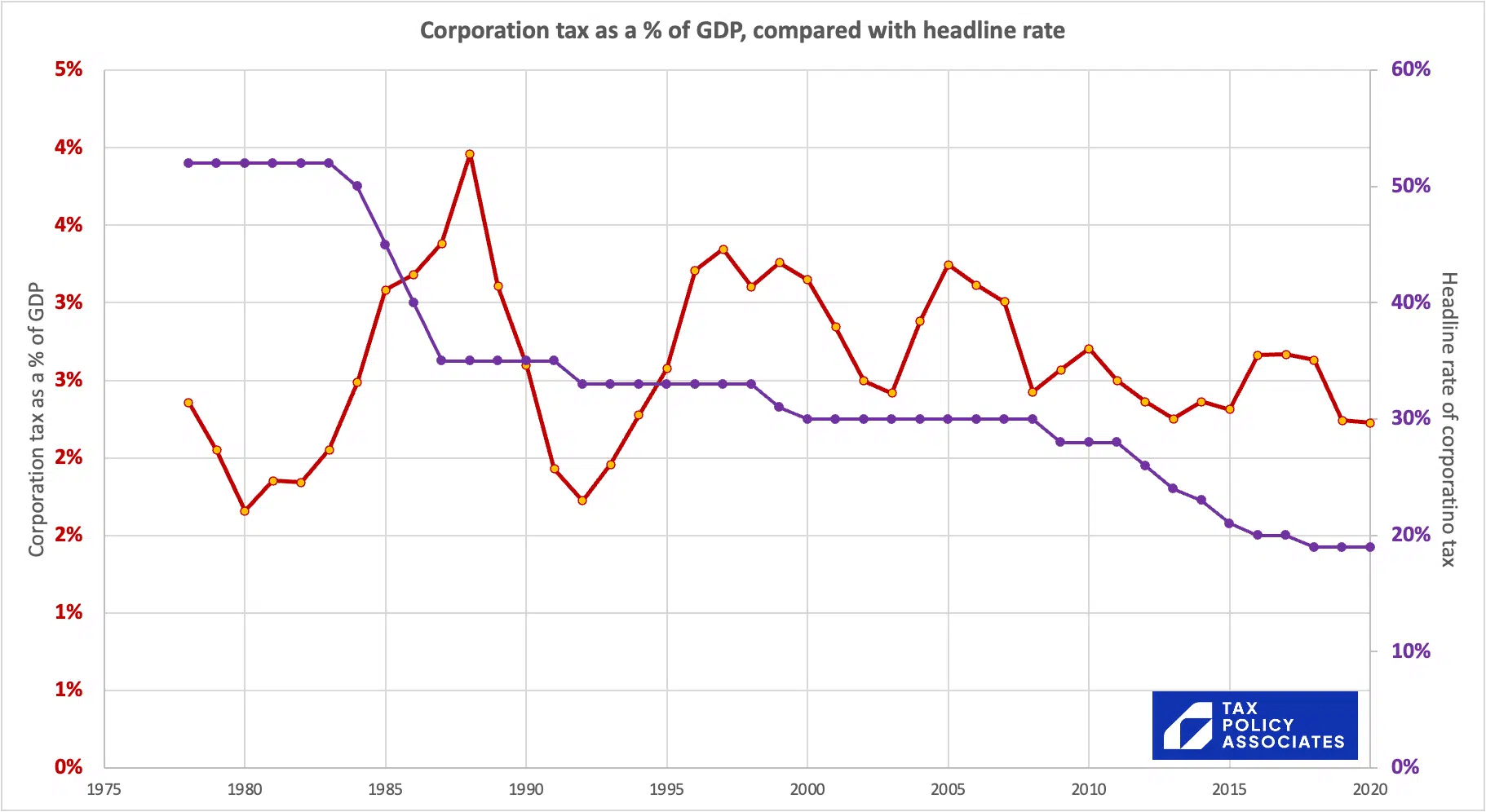

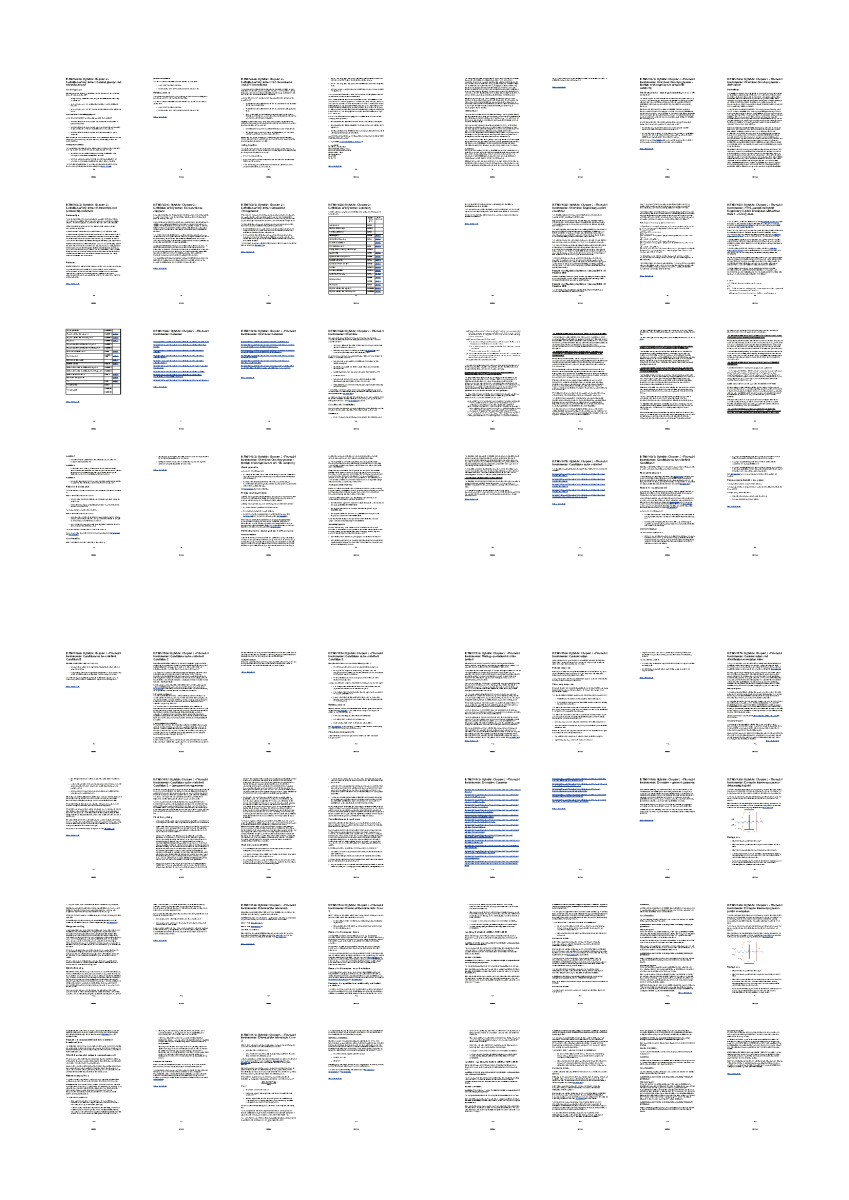

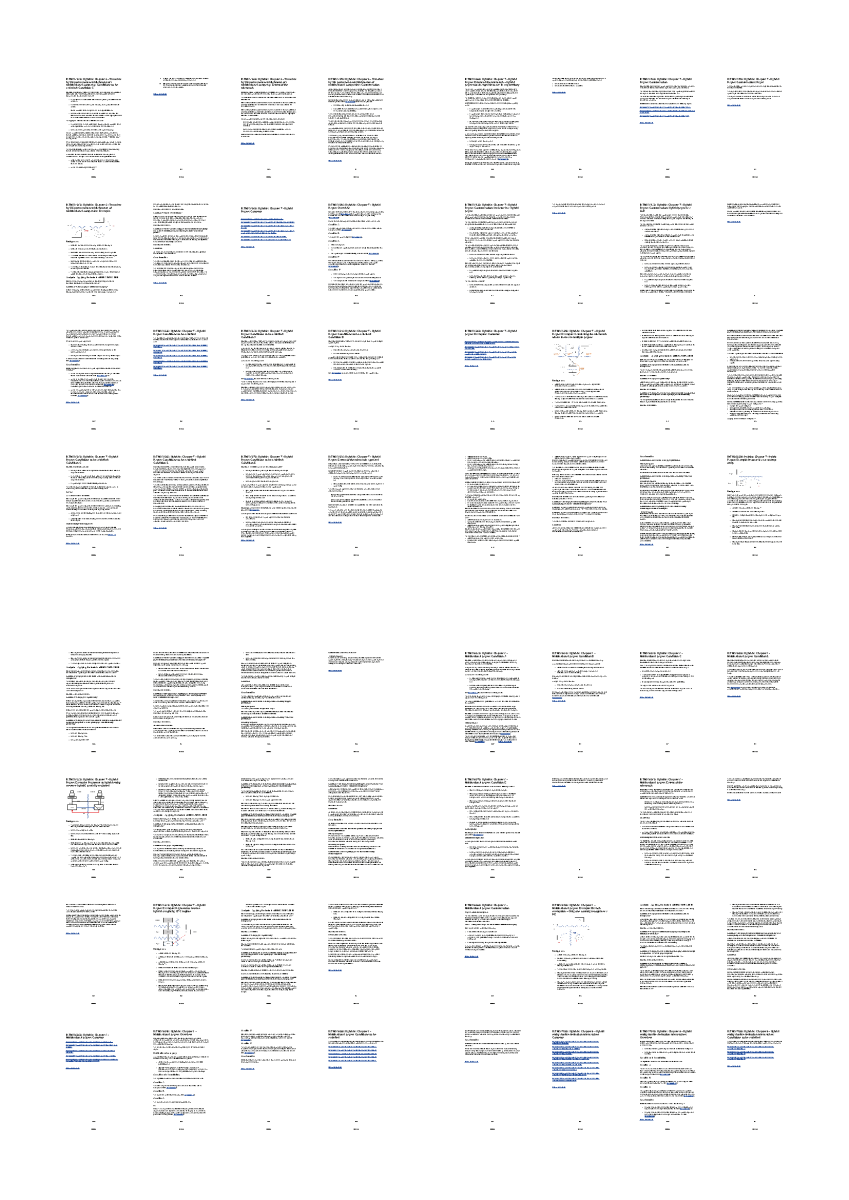

It’s always obvious when the rate changes, but changes to the base can be much less obvious. So, for example, the rate of UK corporation tax fell precipitously from 1980 to 2017 – and lots of people noticed that. However, over the same period – and unnoticed by most non-specialists – the base expanded dramatically. The interaction between these two effects meant that the actual corporate tax paid (as a percent of GDP) was largely unchanged over this period:1

So the base is important.

But the UK’s corporate tax base is uncompetitive.

The UK’s corporate tax base is a mess, largely thanks to a mixture of historical accident and modern over-complication. If we reform the base, we could collect the same amount of tax, but reduce complication, create better incentives and make the UK more competitive – all of which would enhance growth.

My personal experience is that the complexity, uncertainty and constant change of the UK tax base deters foreign investment. However we can obtain a more dispassionate take on how the UK looks from outside thanks to the corporate tax competitiveness work carried out by the Tax Foundation, a US tax think tank.

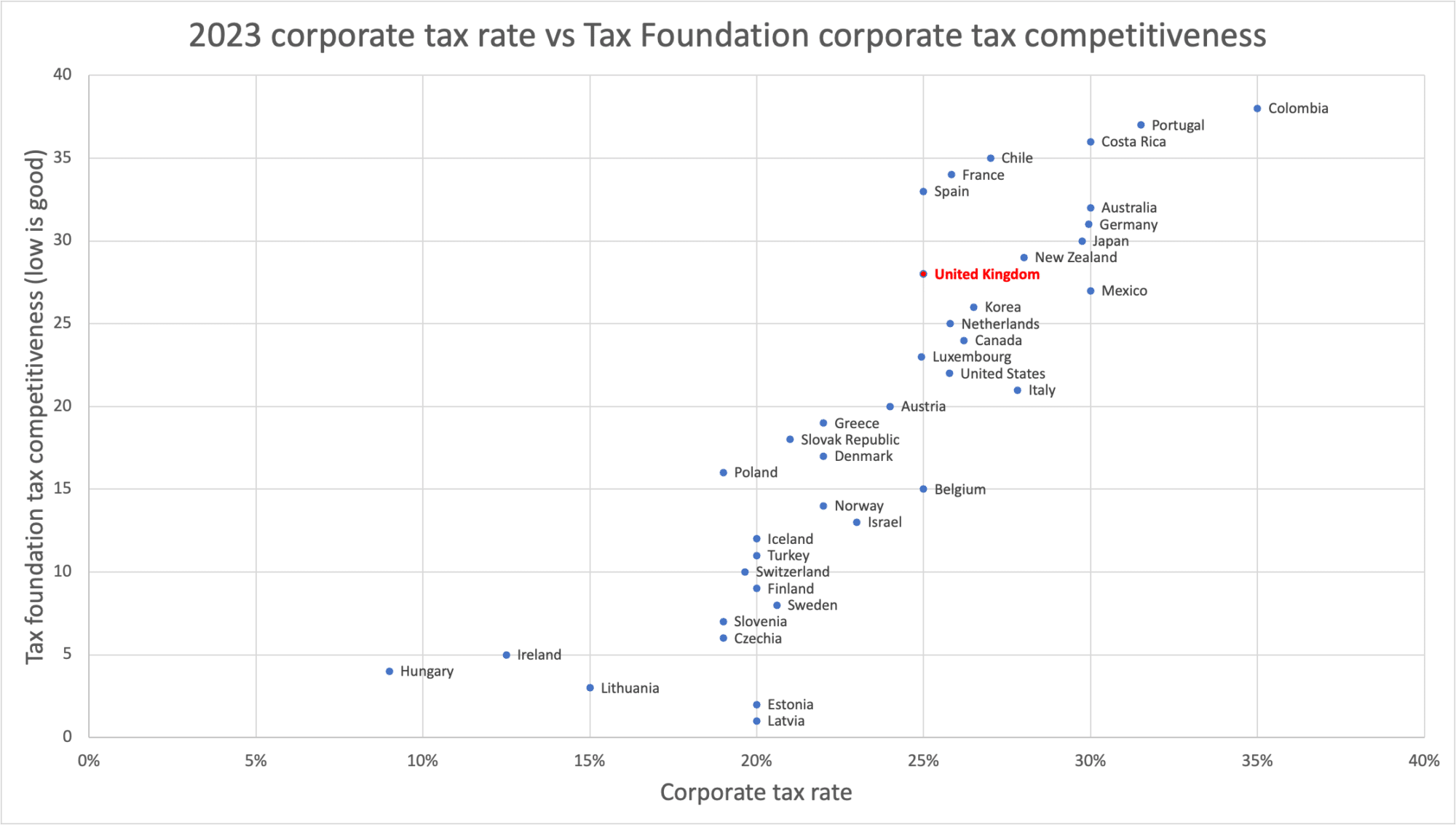

The Tax Foundation ranks every OECD country’s tax competitiveness, looking separately at different taxes. Each country’s ranking (1 is the best) is of course significantly driven by tax rates – but not only by tax rates.

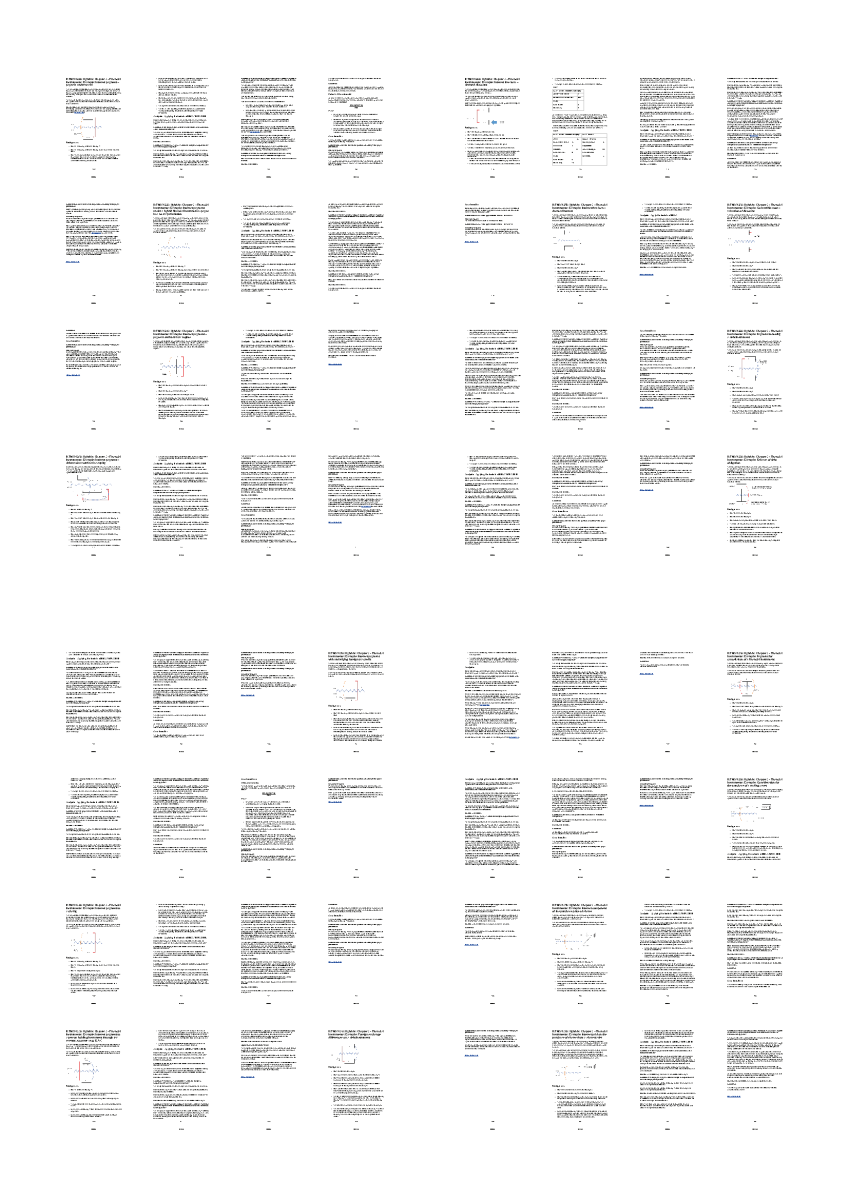

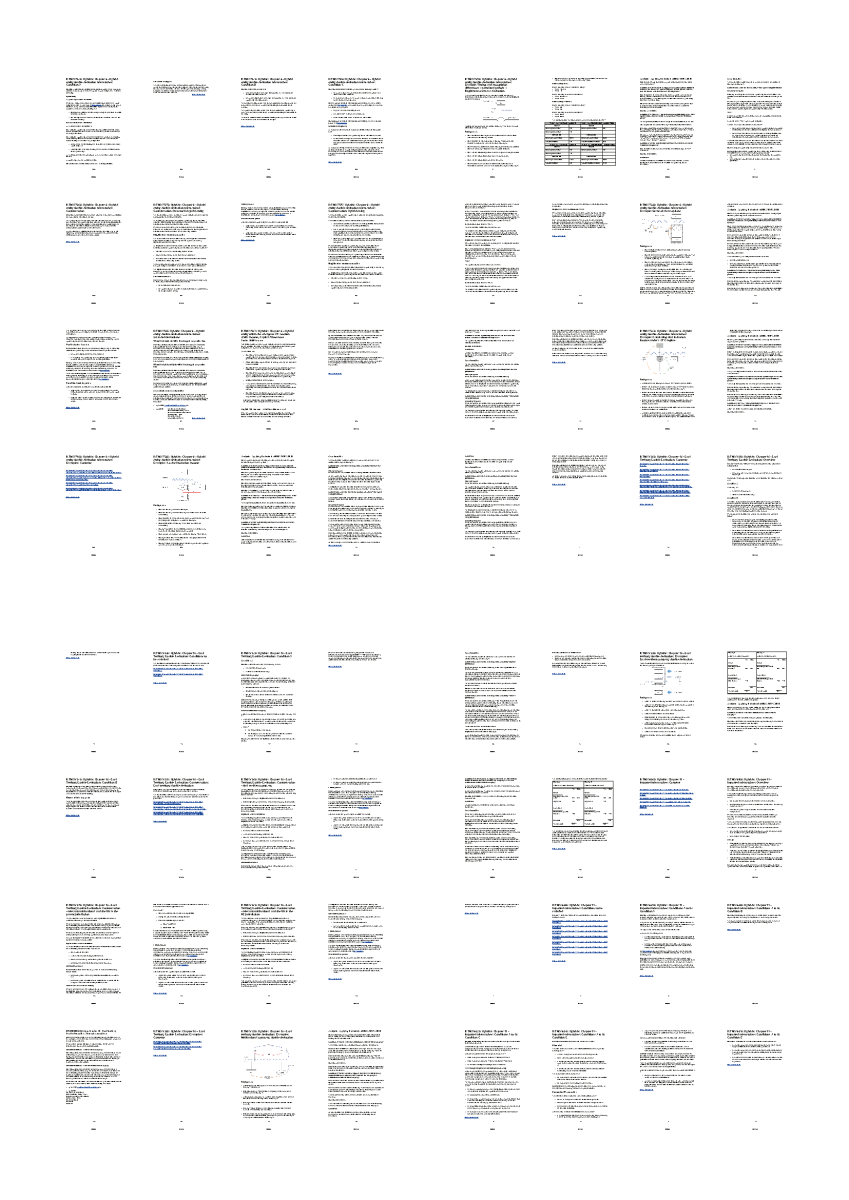

Something interesting happens if we plot corporate tax rates against the Tax Foundation’s corporate tax ranking for each country. We see that the UK is much less competitive than other countries with similar rates of corporate tax. Indeed less competitive than Korea, Italy, Austria and Belgium, all traditionally thought of as high tax jurisdictions:2

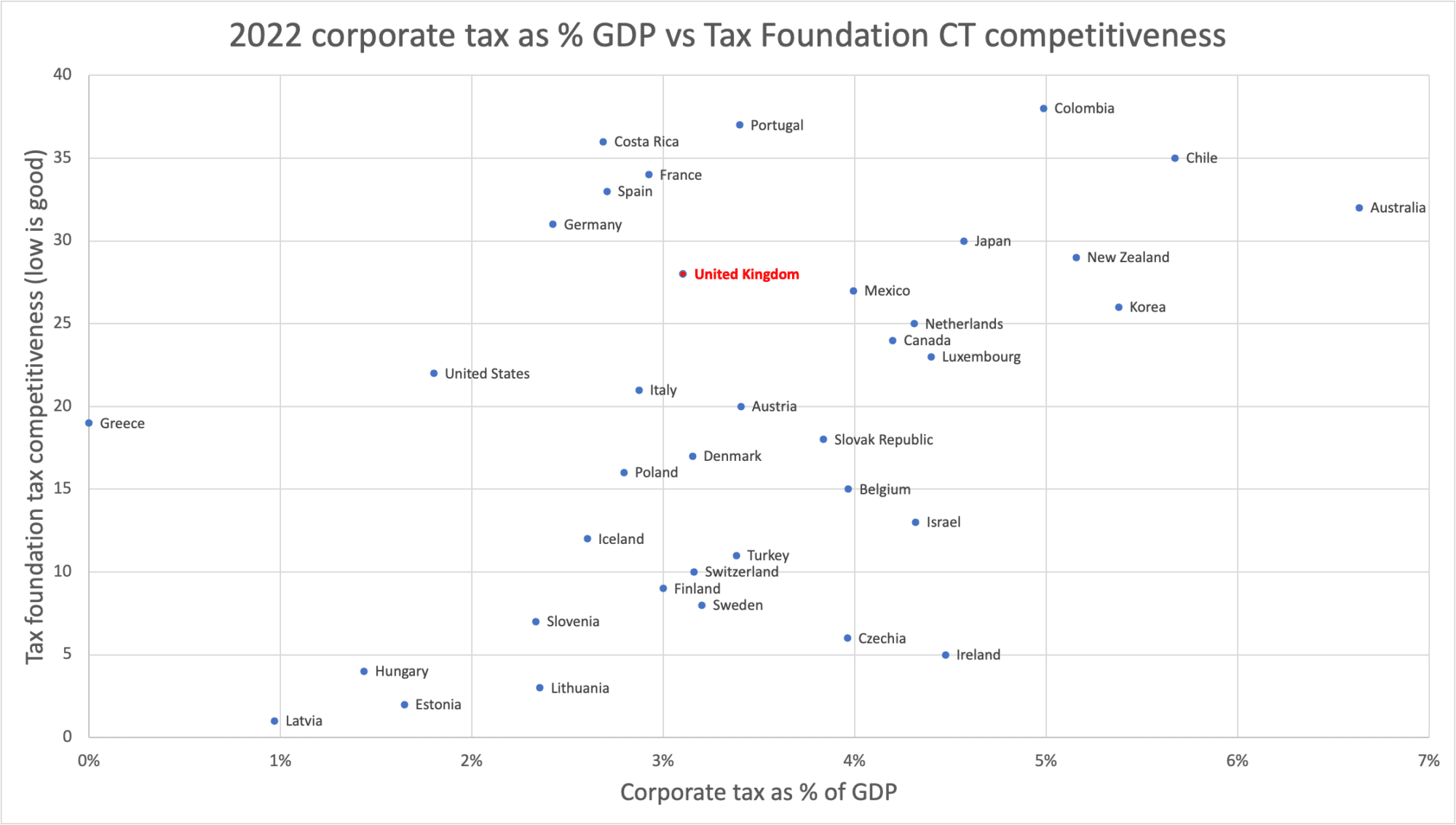

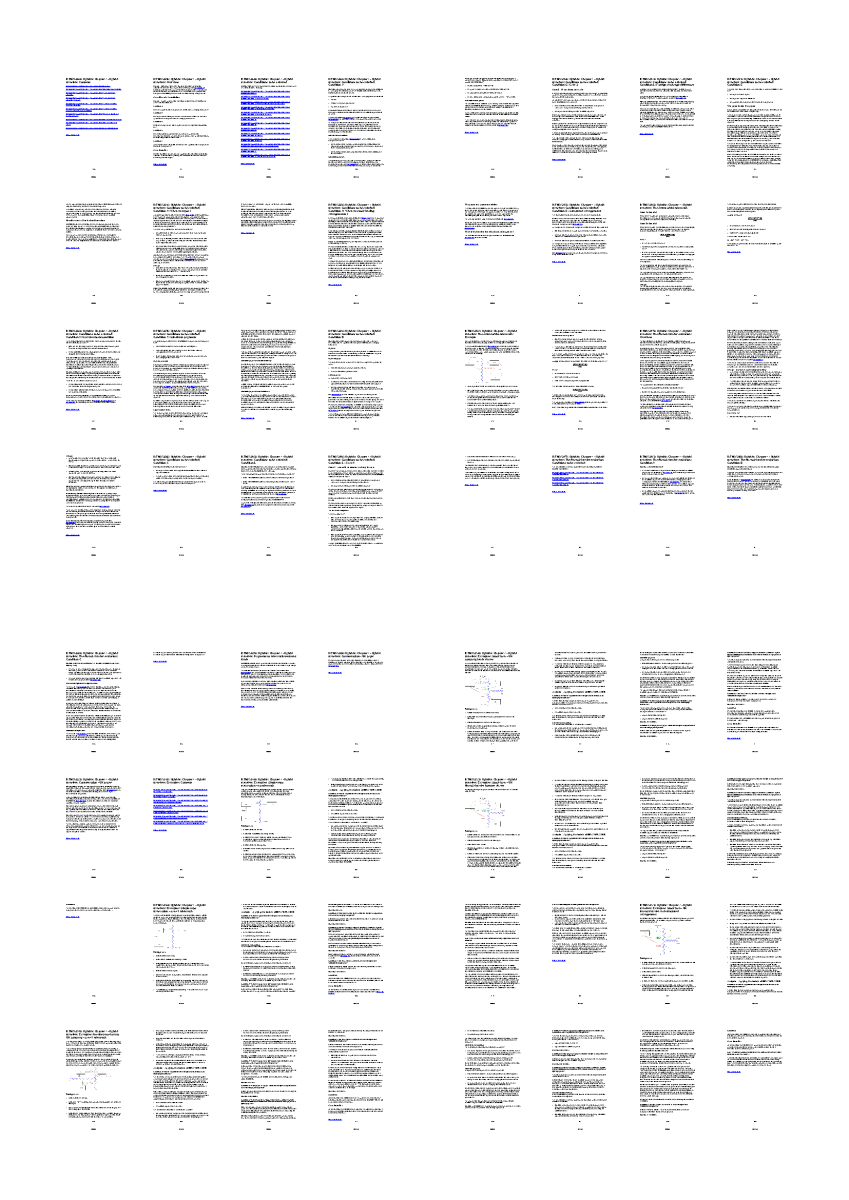

It’s not just the rate – we see the same effect if we plot corporate tax revenues as a % of GDP against the Tax Foundation’s corporate tax ranking. Many countries raise as much or more revenue than the UK, but have more competitive systems.3

So, to put it crudely, corporation tax reform should aim to move the UK vertically downwards in these charts. We can’t be Singapore or Hong Kong4, but we absolutely could be Finland or Sweden.5

We could collect the same amount of tax, but with a better and more competitive6 tax system.

(Or raise corporation tax, or lower corporation tax, as per your preference – nothing in this article is about the overall revenue raised).

The solution: radical simplification

Much of the reason for the UK’s poor performance in the Tax Foundation study is complexity.

An obvious measure of complexity is the sheer length of UK tax legislation. But to get a real sense of what it means in practice, one has to look at the actual steps a business has to go through to work out what its tax liability will be.

I went through an example last year. I looked at a typical and fairly straightforward arrangement: a US parent company financing its UK subsidiary, and went through the main rules the subsidiary would have to go through to establish if its interest payments were tax deductible. There were nine, often overlapping, and involving thousands of pages of legislation and guidance.

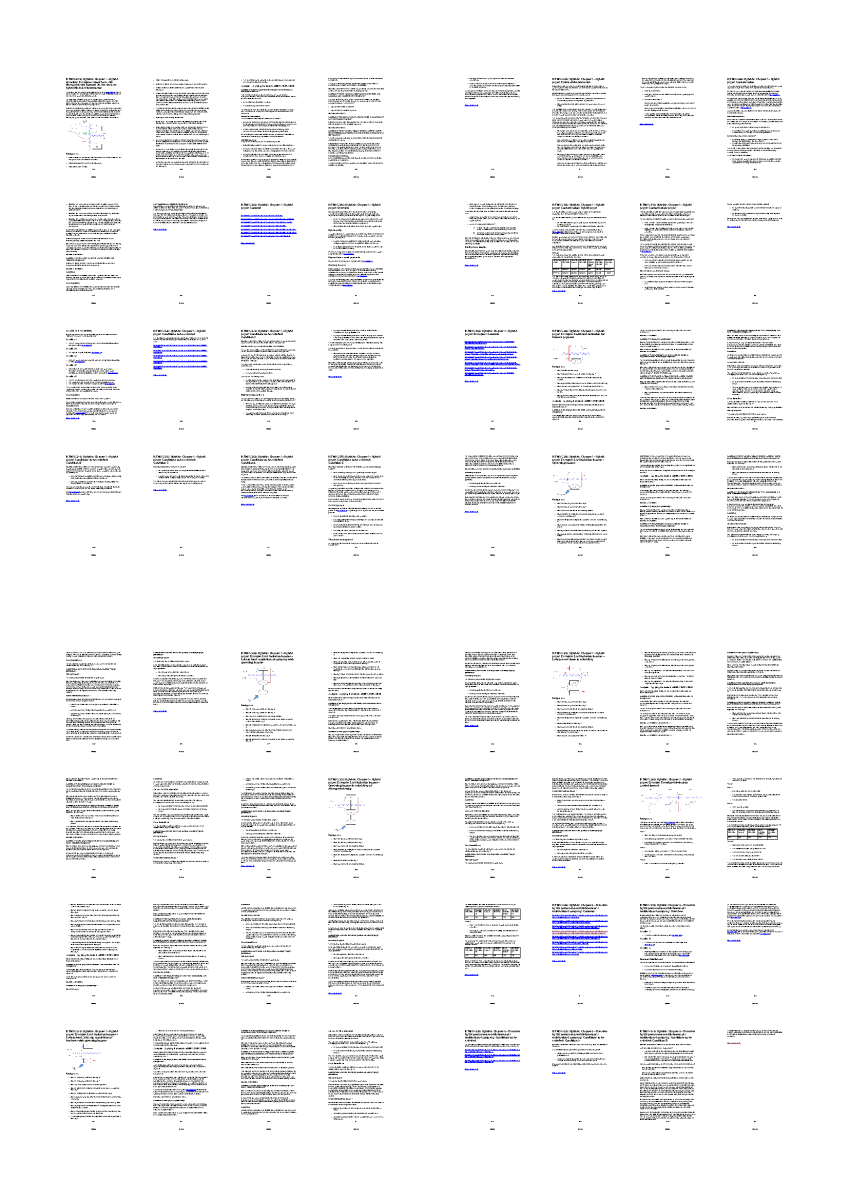

The worst of the nine was the UK “hybrid mismatch rules”, which aim to stop companies achieving a tax advantage by structuring an arrangement so it’s treated differently in two different countries. That principle is easy to state. The detail, on the other hand, is out of control – the guidance alone runs to 484 pages:

All of this complexity carries a cost.

Most obviously: companies spend time and money on tax accountants and tax lawyers. Without that, they wouldn’t be able to carry on in business. It’s facile to say we’d better off if the accountants and lawyers didn’t exist – we’d be worse off. But we would absolutely be better off if the need for tax lawyers and accountants was significantly reduced.

There’s also a cost in lost investment. Tax complexity creates tax uncertainty (and many of the nine rules I went through in the article linked above are deeply uncertain in their application). There is good evidence that tax uncertainty hinders investment.

I believe the complexity is mostly unnecessary. It has two main causes.

- First, the complexity is a fossilised remnant of a 70-year arms race between HMRC and tax avoiders. But the war is over. The attitude of the courts, and modern anti-avoidance rules, means that classic tax avoidance is dead. It’s time to recognise this, and repeal the hundreds of pages of rules that are no longer needed. Whilst at the same time making clear that HMRC will pursue anyone trying to take advantage of “loopholes” created by the repeals.

- Second, the historic common law approach to legislative drafting has reached its limit in modern internationally-coordinated tax rules. The result has been legislation and guidance of exquisite detail and painful length, which in practice fails to achieve the certainty that the common law approach always prized. We need to move towards principle-based drafting of complex rules.

The Office of Tax Simplification produced dozens of reports, running to tens thousands of pages, which could have achieved really significant simplification. But it never received political support, and very few of its proposals were enacted. That was a bad mistake. The abolition of the OTS was a recognition of a political failure by successive Ministers, not a failure by the OTS.

In the medium term, we need a kind of new OTS – but one that has heavyweight political support, and with a junior Minister attached, so that it is a body with real political weight.

In the immediate term, Rachel Reeves should lock some current and retired policy people in a room, and not open the door7 until they’ve identified dozens of provisions that can be repealed. I don’t think this is a difficult task.

A more ambitious solution: real full expensing

There are lots of problems with the UK tax base. But perhaps the biggest one is the oldest: companies can claim a tax deduction for their ordinary expenses (“revenue”) but not for investments (“capital”). This distinction doesn’t follow economic or accounting concepts; it’s purely a tax invention.8

It’s clearly suboptimal that the tax system incentivises current expenditure over investment. So the rules create a special case where companies can claim relief (“capital allowances”) for a certain type of investment – “plant and machinery”.

Capital allowances used to be claimed over time; now they’re usually claimed up-front, in “full expensing“.9 But again that’s only for “plant and machinery”.

What’s plant and machinery? Inevitably, that’s not actually defined, although there are many rules excluding particular things (like buildings). There used to be an “industrial buildings allowance” which was very valuable to industry, but Gordon Brown abolished that in 2008 to fund a 2% cut in the rate. A more limited “structures and buildings allowance” was introduced in 2018.

This complexity is a problem. It creates uncertainty, which makes it hard for companies to plan, and therefore reduces the incentivising effect of the reliefs. It also creates a curious incentive towards investing in the particular types of asset which qualify – and there’s no good reason for this. Investing in buildings, intellectual property and other intangible assets should be treated in the same way.

The answer is simple: give up-front tax relief for all business expenditure.10 End the capital/income distinction.11 Real full expensing.

If that’s the only reform that was made, it would be very expensive. It would also exacerbate the current distortion in favour of debt finance – you could claim tax relief twice for the same asset (once for the purchase of the asset, once for the financing cost).

Real full expensing therefore has to come with the quid pro quo of ending the bias towards debt, by making interest non-deductible12. There would need to be transitional measures or (preferably) a de minimis (as for the existing corporate interest restriction) to prevent disruption to small business.

The aim should be to not change the overall level of tax on corporates, but to shift incentives decisively in favour of investment and away from financial engineering.

This is an area where plenty has been written – there’s an excellent piece from the IFS here.

Photo © The Labour Party, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Footnotes

This is not a function of cherry-picking particular measures; however you cut it, the rate has dropped but revenues have not. ↩︎

Data from the OECD tax revenue database. ↩︎

Data again from the OECD tax revenue database. Note that Greece is excluded because there’s no 2022 data as yet. Norway is excluded because its large oil and gas revenues make it an outlier that turns the chart unreadable. ↩︎

It’s often suggested our tax system could be as simple as Hong Kong’s, which runs to a few hundred pages. But it’s clearly unrealistic to expect the UK (where government spending amounts to 45% of GDP) to have a tax system that looks anything like Hong Kong or Singapore (15% of GDP). City states with a very high proportion of highly paid financial sector workers are not remotely comparable to large diverse economies like the UK. ↩︎

Finland and Sweden are often viewed as high tax jurisdictions. From a personal tax perspective that is accurate. From a corporate tax perspective, the overall burden is similar to the UK; but the corporate tax systems are significantly simpler. ↩︎

“Tax competition” is a bad word in some quarters. But, whatever you think about tax competition over rates, tax competition over complexity is a good thing. ↩︎

Figuratively speaking. I am in not generally in favour of unlawfully detaining tax advisers. ↩︎

And a distinction that’s often very unclear, being entirely a creation of common law and not legislation. Advisers spend significant time advising whether a particular transaction is capital or income, and often end up having to advise on both bases, just in case. ↩︎

There is a good guide to the rules from PwC here. ↩︎

i.e. expenditure satisfying the “wholly and exclusively” test. ↩︎

The change would probably have to be prospective only in relation to losses. Many companies have huge amounts of historic capital losses which can’t be used against current (revenue) profits. There is no principled reason for this, and it should be changed going forwards. But enabling utilisation of historic losses would be very expensive; my belief (based on personal experience across the large business and financial institution sector) is that it would cost several billion pounds. ↩︎

Excluding financial traders, such as banks, where interest income and expense is a fundamental part of the business. Taxing interest income but not giving a deduction for interest expense would end banks’ businesses overnight. Permitting a deduction for interest expense, but only against interest income, would result in distortive behaviour and avoidance. The Mirrlees Review discussed this problem in detail; I would duck it entirely by simply exempting financial traders. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Barry Skillett Cancel reply