Until last week’s Budget, someone earning £50k with three children under 18 faced a marginal tax rate of 71%. That was deeply unfair to those affected, and damaging for the country as a whole. So it’s great news that this marginal rate has been cut to 57% – about 500,000 families will benefit. But other high marginal rates remain in the tax system – the challenge is how to fix them fairly, without the burden falling on people on lower incomes.

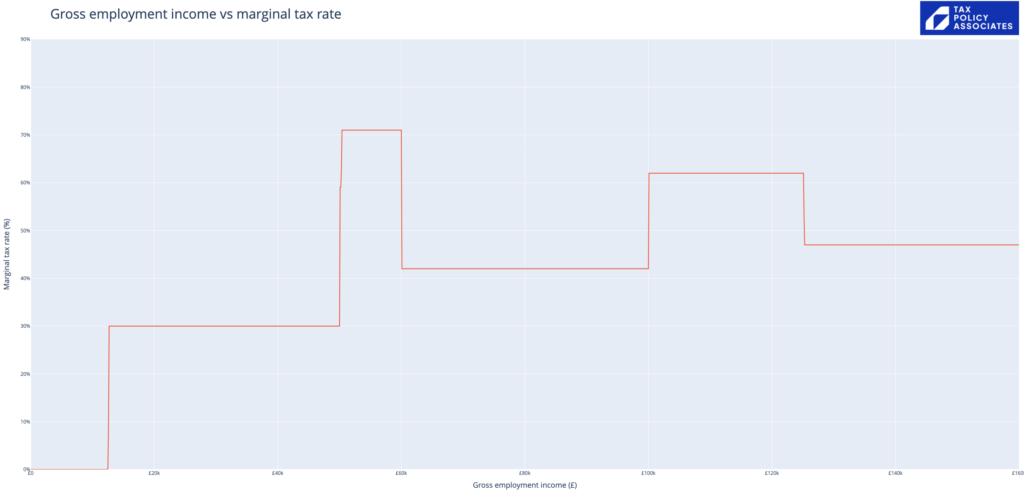

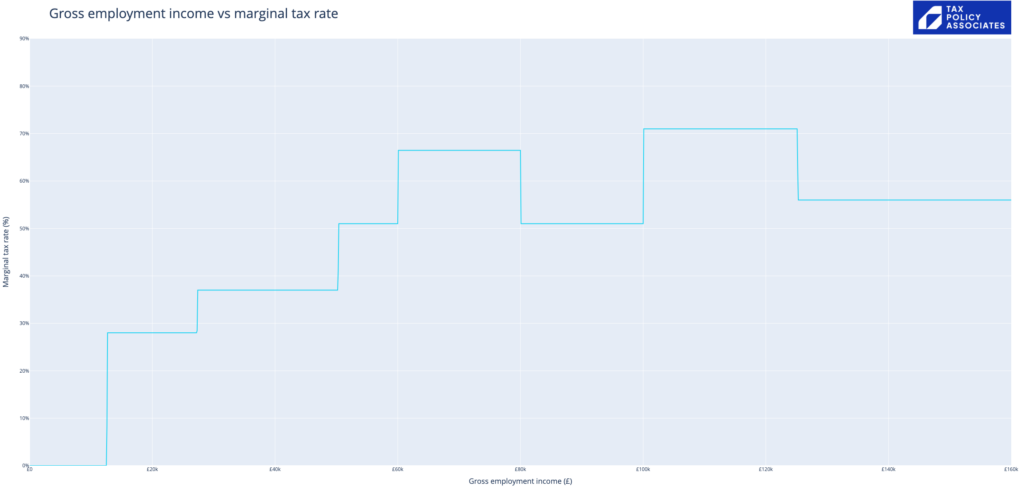

In the run up to the Budget, we and many others were concerned about the very high marginal tax rates hitting parents earning £50-60k. This chart shows how the marginal tax rate (y axis) varies with gross employment income (x axis) for someone with three children under 18:

(If you click on this chart and the others below, you’ll go to an interactive version that lets you see the effects of the various different marginal rates for the UK and Scotland).

The “marginal tax rate” is the percentage of tax you’ll pay on the next £ you earn. The tower at the £50-60k point shows the marginal rate hitting 71%. The reason: the phasing out of of child benefit (via the “high income child benefit charge”) that started at £50k. So when your earnings hit this level, you’d take home only 29p for every £ you earned. For many people that wasn’t worth it – so they chose to work fewer hours. That’s bad for the UK as a whole.

This is why the marginal rate is so important – it affects the incentive to work more hours/earn more money.1

The marginal rate of tax in the UK for high earners in theory caps out at 47% (45% income tax plus 2% national insurance2) once you get to £125,140. I’m not terribly convinced this disincentivises anyone to work (and I spent many years working in an environment surrounded by colleagues and clients paying tax at this rate). But once you get to marginal rates of well over 50%, things are very different.

The Hunt solution

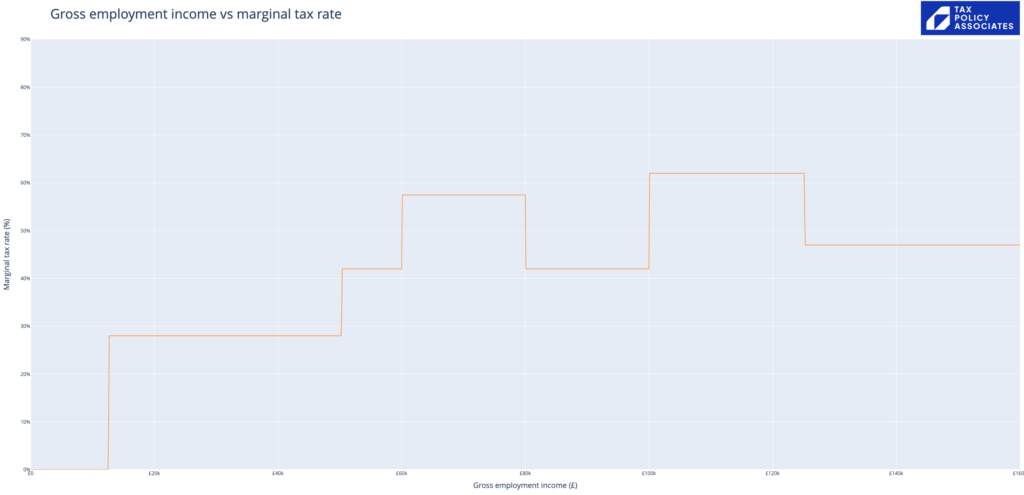

I’d like to see a complete end to the child benefit taper, paid for by a slightly higher tax rate on high earners. Jeremy Hunt didn’t do that. But he pushed out the start of the taper from £50k to £60, and made the phasing gentler, running from £60-80k instead of £50-60k. That, and the national insurance change, means the chart now looks like this:

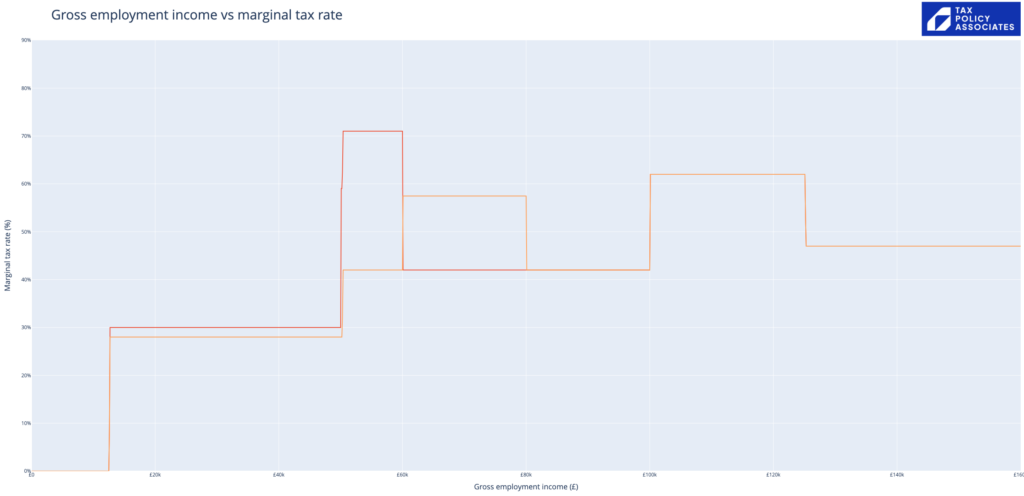

We can overlay the two – 2023/24 in red and 2024/25 in orange (although it’s not terribly readable; you can play with the different rates on the interactive version of the charts here):

The longer taper period means that the top marginal rate has fallen from 71% to 57% – but of course this rate applies across a wider range of incomes. A less serious effect, but more people affected.

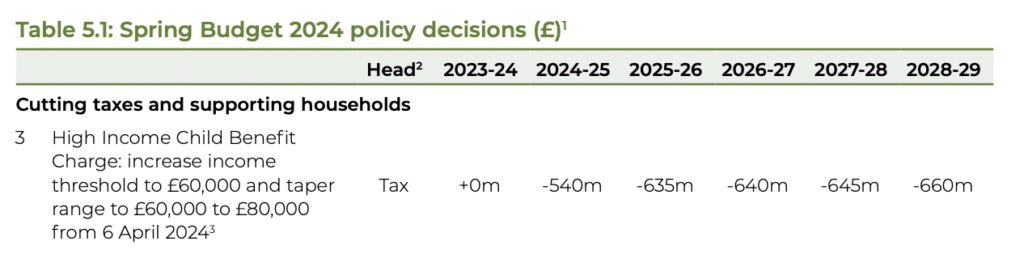

This cost about £660m:

And more radical change is promised. One of the unfairnesses of the child benefit taper is that it applies to a household if one earner hits £60k in income; it doesn’t apply if (for example) there are two earners, both on £59k. The promise is that this will be fixed by applying the high income child benefit charge to household income, not individual income. That faces a number of practical and technical challenges. I’d simply abolish the taper and the high income child benefit charge altogether.

What’s the highest marginal rate now?

Even after Hunt’s reforms, with three children under 18, the tapering of child benefit takes the marginal rate to 57%. It’s very odd that someone earning £60-80k has a higher marginal rate than someone earning £1m.

And there are other anomalies.

Personal allowance taper

The personal allowance – the amount we earn before income tax kicks in – starts to be tapered-out if your salary hits £100k, and is gone completely by £125k. That’s responsible for the second tower on the chart above – a marginal rate of £62% between £100k and £125k.

And if we add in student loans, which are really just a complicated hidden graduate tax…3

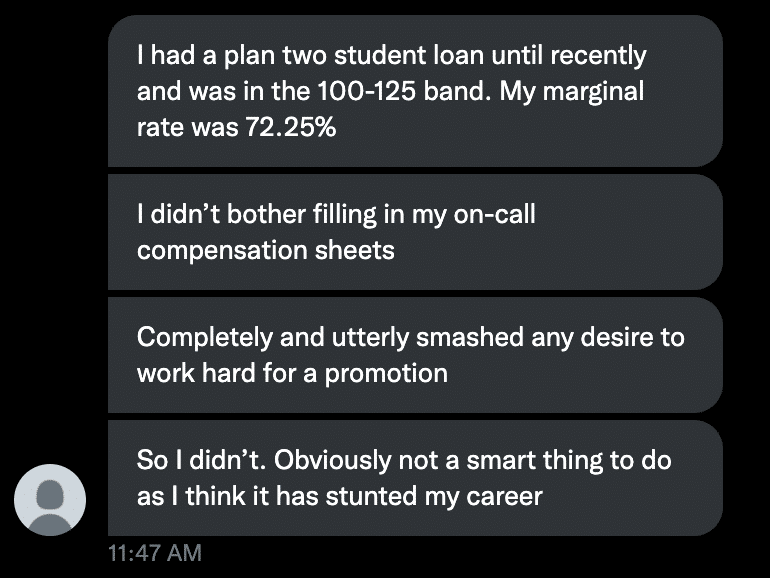

… we see a top marginal rate for someone earning £100k of over 70%. This isn’t just theoretical – we’ve received lots of messages like this:

That’s a problem for all of us, just not just those personally affected.

There’s not much popular appeal in cutting taxes on people earning £100k. But it would be the right thing to do – the challenge is how to do it without increasing the tax burden on people earning less. The obvious answer is to slightly increase tax on everyone earning more than £100k – for example with a new 45% marginal rate on people earning £100k and a new 48% rate on people earning £125k.

But the tax raises required to fund an end to the taper may be significantly less than this, given the widespread “avoidance” of the 60+% rates by people making additional pension contributions, or simply working fewer hours/turning away work.

Childcare subsidy

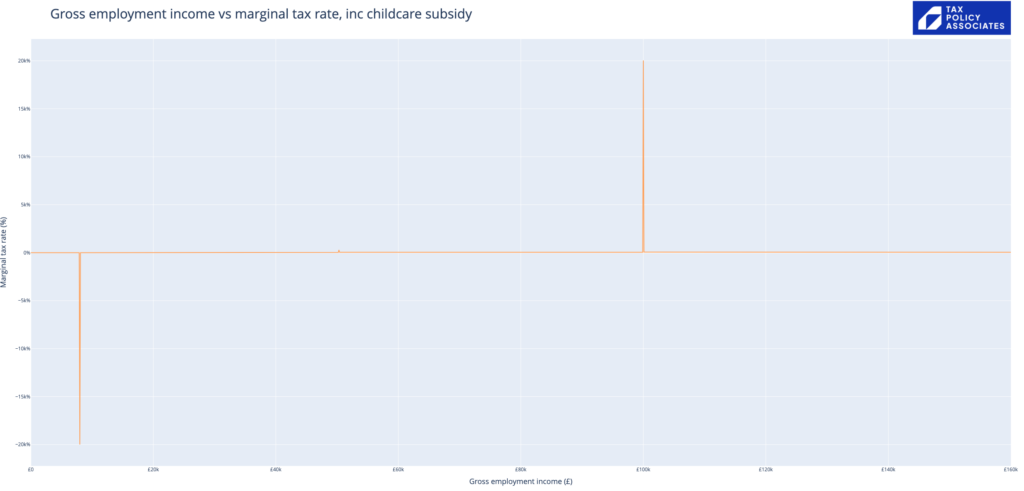

The Government has created a new childcare support scheme for parents with children under 3. This could be worth £10,000 per child for parents living in London, once both parents have income of £7,904. And it vanishes completely once one parent’s earnings hit £100k. That does impossible things to the marginal tax rate:

That’s a marginal rate of -20,000% when the parents become eligible for the childcare, and a marginal rate of 20,000% when they lose it at £100k.4.

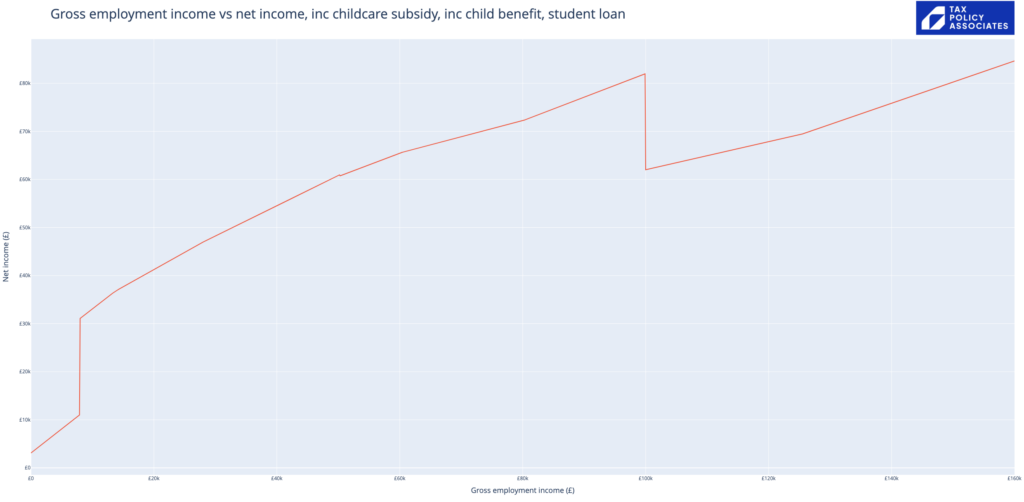

It’s easier to see what this means if we plot the gross salary vs the net salary:

As your income hits £100k, you lose £20k of net income, and that doesn’t recover until you earn £154k. Clearly no rational person in this position would earn between £100k-£154k if they had a choice, and that’s a deeply irrational result.

This all relates to the new childcare subsidy, and not the pre-existing tax-free childcare scheme, which also vanishes at £100k. The benefit of tax-free childcare are less (usually under c£7k/child) so the curve for that looks less dramatic. However, as the scheme applies to children under 11, taxpayers feel these effects for many more years.

Where next?

If a political party went into an election promising a tax system with these marginal rates, there would be uproar. But instead, we’ve drifted into this disaster over many years, with the topic entirely absent from public debate.

That’s now changed – and that’s a good thing for the country as a whole. The challenge is how to make further progress, and eliminate anomalous marginal rates without raising tax on everyone else.

And the other key challenge, particularly for the next Government, is resisting the temptation to introduce further tapers into the tax system.

Official portrait of the Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt by Andrew Parsons / No 10 Downing Street. Crown copyright.

Footnotes

Everything interesting happens at the margin. For more on why that is, and some international context, there’s a fascinating paper by the Tax Foundation here. ↩︎

Note that I’m not including employer’s national insurance here. Employer’s national insurance is absolutely a tax on labour in the long term, because it reduces pay packets in the long term. But it’s not usually included in a calculation of a marginal tax rate, because it’s not economically passed to you in the short term, and so it won’t rationally affect your decision whether or not to work more hours. There’s a good explanation of this point here. ↩︎

For someone starting university between 2012 and 2023, you pay 9% of your salary over £27,295, until the loan is repaid. Of course, the effect on individuals – even those on the same income – will vary widely, depending on how much loan they borrowed, how long they’ve been earning, and how their salary ramped up over time. ↩︎

The 20,000% figure is rather arbitrary, and a result of the code having a resolution of £100 of income . If the resolution was 1p then the marginal rate would be 200 million percent. But the concept of a marginal tax rate doesn’t really work in this scenario ↩︎

11 responses to “The Budget tax cut nobody’s talking about, and why we need more”

Good article highlighting the daft tax system we have. I agree that abolishing these marginal rates would probably increase the tax take and drive productivity. I am fortunate to earn over 100k and like many others I salary sacrifice into my pension to avoid the 62% rate. It’s of course excellent for my pension, but I wouldn’t be doing it if the tax rate was normal and would pay more tax (albeit my pension will be taxed on due course but at a lower rate)

A great post as always. It repeats the only thing I have ever really disagreed with you on though. The idea that individual rather than household income basis here is an “unfairness”.

For two parent, single income households the work of the non earning partner is entirely untaxed. Whilst this is very sensible, compared to a single parent who is paying for a non family member to do all the childcare, cooking, cleaning, family PAing etc the two parent one earner family gets a far better deal tax wise. The same overall work is done in both cases but it is taxed very differently.

Of course it would be ridiculous and wrong to try to tax unpaid domestic labour within families but the idea that a family with two £31k salaries are better off than a family with one £61k salary and one full time stay at home parent is also wrong. The implicit (and in my opinion wrong) assumption behind this idea is that the unpaid work done by stay at home parents has zero economic value for the family.

Of course, as so often, the real losers in the system are single parent families or those with one parent unable to work who should not just be given better tax/benefit treatment but some sort of medal as well.

You make a reasonable point at the margins, but whilst it is true that a family with one high earning parent and one stay at home parent may have some advantages in theory vs two parents earning the same in aggregate but paying for childcare, its import to recognise that (1) the single high earner is already paying a significantly higher effective tax rate in many cases (if they are a higher or additional rate taxpayer), (2) the crux of this issue is free/subsidised childcare, which eats away at the core rationale of your argument (which is that the dual income household has extra childcare cost), because for the significant majority of dual income households the bulk of cooking/cleaning/admin etc is still done by the parents, families who can afford to outsource all domestic tasks may be paying more tax (although given that subsidised childcare is available for the families we are discussing, I’m not sure how much tax this really is, most cleaners aren’t registered for VAT and very few people have a cook – those who can afford full outsourcing probably aren’t doing so without at least one parent earning £100k+), (3) you have raised this in the context of dual income households which are about the same in aggregate as a single high income household, but this issue is also relevant and most unfair when the dual incomes are actually significantly higher than the single income (e.g. where households with total income of nearly £200k are getting free childcare when households with total income of £100k via one earner don’t).

I can’t have been clear. My point isn’t, as you say, that dual income families have higher childcare costs in fact it’s the precise opposite.

Dual and single income families have exactly the same childcare costs but single income, dual worker, families choose to meet this cost through unpaid stay at home parenting. In London, google suggests the value for this labour (assuming equivalent to a full time nanny) is c. £40k. Not paying any tax on that labour provision is a benefit of £9k, which far exceeds any loss of child benefit which is the main point of the article.

I agree the cliff edge on childcare at £100k is a terrible system (as Dan neatly shows above) and should be revised but given the inherent tax advantage of stay at home parenting, making it subject to a whole family test will probably make it less fair rather than more. There are other far more sensible revisions which would avoid this.

“For two parent, single income households the work of the non earning partner is entirely untaxed.”

The UK doesn’t tax work; it taxes the income received for doing work. Which is just as well as the taxpayer would have no income out of which to pay the tax. I think I’d be a bit miffed if in running the vac round or changing the beds I increased my tax bill.

An excellent article Dan (and colleagues) and your work on marginal tax rates is really helping highlight this issue.

However, I’m perplexed at your view that the ‘cut’ has to somehow be ‘paid for’ by higher taxes elsewhere to avoid the burden falling onto lower rate taxpayers. Leaving aside the not unreasonable view that cutting expenditure would be a better option, my point is that if this is such a disincentive to work harder (my own experience from younger colleagues and my own grown-up kids is that it absolutely is) then the net tax take may not fall at all or even grow as those affected do more overtime/bank shifts/go for promotion/take on more contracts thus raining more tax revenue so surely it’s just worth cutting it and giving time for the changes to bed in before trying to fund it by raising tax elsewhere?

I am more concerned about the £10 an hour employees and thus I think the Tax Free Allowance should be raised to £20,000…

This would reduce the Govt Benefit expenditure

A similar nonsense applies to universal credit. When someone takes on a new job they lose 55% of their UC? There’s really no incentive to work!

All this is true but it treats MDR as a fixed element for varying levels of earnings. We should also look at what happens when earnings increase, that what the government say that they are trying to use tax policy for – persuading people to increase their hours of work and pay. Fot low earners, many dependent on in-work benefits, that can paint a very different picture. I wrote about this in my blog a couple of years ago with some detail on the very different MDRs on each additional pound of earnings, because of a number of other factors in tax and benefit rules. I have updated the core NLW figures since, in latwer posts, but the basic effects and charts remain valid. You can see those at https://benefitsinthefuture.com/2022-a-better-year-for-generous-work-incentives-how-the-government-is-really-doing/ .

If we take all of these effects together, how succesful would we be if we wanted to find someone who would say that, if we started with a blank sheet, we should design the current system?

“I’m not terribly convinced this disincentivises anyone to work (and I spent many years working in an environment surrounded by colleagues and clients paying tax at this rate)”

I wonder if this is a form of survivorship bias? CC is not exactly a typical place to work when compared to the population as a whole.

I would also imagine, as I did, that many people will be undertaking a number of strategies to reduce that amount – ISAs, SIPPs etc.

@Greg, I think Dan is right that it doesn’t stop people trying to earn more at rates under 50%. That doesn’t stop them exploring all ways to reduce the amount subjected to tax. I advise my children to put more into their pensions to minimise the Student Loan (Tax) that they have to pay.

I believe there should be no tapers, that all income should be taxed at least as much as earned income and that there should be a wealth tax (similar to the Green Party suggestion).

I don’t think this should be too difficult to work out, but the political will is certainly not there universally yet.