Stamp duty was one of the triggers for the American Revolution. Somehow, 250 years later, we still have it. That makes no sense – it raises no money, is pointlessly complex, and creates cost and uncertainty for business. The Government should abolish it.

Update: In March 2025, the Government announced the results of a consultation into stamp taxes; it looks very much like stamp duty will indeed be abolished.

350 years ago, stamp duty made perfect sense. The State had limited power and resources, and collecting tax from people was hard. So some unknown genius had a brilliant idea. Impose a special duty on documents. No need to have an army of tax inspectors. But if you wanted the document to be used for any kind of official purpose, you’d have to pay to get it stamped. No official would accept an unstamped document, for fear of being thrown into jail. Beautiful simplicity – a tax that doesn’t need an enforcement agency.

Stamp duty once applied to basically everything. Even tea1 – which helped spark the American Revolution. Over time, it’s shrunk and shrunk, and today it’s basically irrelevant. But still there, and still costing business millions in legal fees.

At this point I should clarify that I’m talking about old-style stamp duty, the one that actually involves things being stamped2. I’m not talking about the two modern taxes that emerged from stamp duty, but work in a sensible modern way:3 stamp duty reserve tax (SDRT – which applies to shares), and stamp duty land tax (SDLT). Both are often referred to as “stamp duty”, but they are separate taxes.

What does old-style stamp duty actually cover?

Given SDRT applies to securities, and SDLT applies to land, what does stamp duty do?

Answering that question is surprisingly hard, and requires a level of nerdy detail not really suitable for a blog post or twitter thread. But it demonstrates the insanity of the tax, so I’ll do it anyway:

- The principal charging clause is paragraph 1 of Schedule 13 to Finance Act 19994. This says that stamp duty is chargeable on a transfer on sale, and paragraph 7 extends that to some agreements for sale. So at this point we think: OMG stamp duty applies to everything.

- But then section 125 Finance Act 2003 says that actually stamp duty is abolished on everything except instruments relating to “stock and marketable securities”. Whew – it only applies to some stuff.

- But what kind of stuff? The definition of “stock and marketable securities” is in section 122 of the Stamp Act 1891, which reads pretty much like you’d expect from 150-year-old legislation:

The expression “stock” includes any share in any stocks or funds transferable by the Registrar of Government Stock, any strip (within the meaning of section 47 of the Finance Act 1942) of any such stocks or funds, and any share in the stocks or funds of any foreign or colonial state or government, or in the capital stock or funded debt of any county council, corporation, company, or society in the United Kingdom, or of any foreign or colonial corporation, company, or society.

The expression “marketable security” means a security of such a description as to be capable of being sold in any stock market in the United Kingdom

- If you stop and squint at this long enough, you’ll probably conclude it means that stamp duty applies to shares and bonds.5

- But don’t stop there, because section 125 is partially undone by paragraph 31 of Schedule 15 to Finance Act 2003 which says that certain partnership transactions are also subject to stamp duty, if the partnership holds stock or marketable securities.

- And we’re still not done, because the George Wimpey & Co case says that options can sometimes be subject to stamp duty, for reasons which don’t make a huge amount of sense, but there we go.6

- And where’s the rule actually saying you have to pay stamp duty? There isn’t one. Stamp duty’s “teeth” are found in section 14(4) Stamp Act 1891, which says that a document executed in the UK, or which relates to the UK, can’t be used for any purpose in the UK unless it is stamped. So, for example, a share registrar won’t recognise a transfer of shares unless you get the transfer stamped. And a court won’t accept a document as evidence if it is stampable, but hasn’t been stamped. In principle your multibillion £ deal could be unenforceable if stamp duty isn’t paid, which would be awkward.7

I should emphasise – this unholy mess just tells us what the tax applies to. How it’s calculated, how the timing works, the scope of the exemptions – they make the above look simple and rational, but are a subject for another day.

So what does this mean in practice?

There are two ways in which stamp duty is actually relevant.

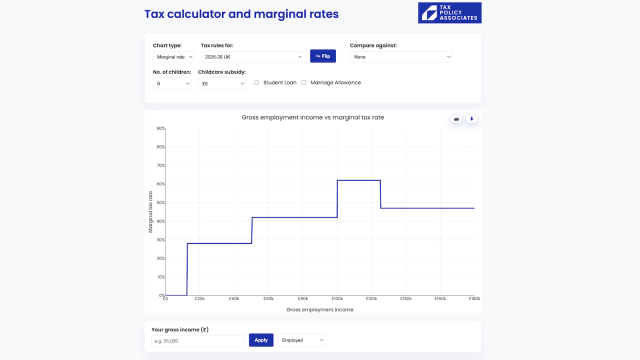

First, whenever shares in an unlisted UK company are bought/sold. People actually pay this, and get their documents stamped – because if they don’t, the transfer couldn’t be registered. But if stamp duty was abolished tomorrow, SDRT would apply instead. So in this scenario, stamp duty is payable but pointless.8.

Second, there’s a whole universe of cases where stamp duty might apply if you were really unlucky, but in practice never does. Some examples:

- Transactions in foreign securities. The UK has no business taxing these transactions, and SDRT (stamp duty’s sensible sister) certainly doesn’t. Stamp duty in theory does tax transactions in Upper Volta, if the transactions have a UK party or are signed in the UK (or otherwise “relate” to the UK, whatever that means). But people normally don’t care – the fact you can’t enforce such a transaction in a UK court doesn’t much matter if the securities are foreign (i.e. because you’d enforce in the relevant foreign court).

- A document might be thought to contain an “option”, and so be technically stampable, even though it’s not realistically an option at all.

- Sales of loans, for example where a bank is selling part of its business to someone else. In practice the loans will almost always be exempt, but establishing this to a level of legal certainty means reviewing each loan. If the purpose of a tax system is to ensure revenue for tax lawyers, then job done.

I have never once seen stamp duty actually paid on any of this second class of transactions. But I’ve seen huge amount of time/money spent analysing the issues. Why? Because if a document is stampable but the duty isn’t paid, then it’s unenforceable. On a large commercial transaction that’s an unacceptable risk.

So there we have it. Stamp duty applies to some transactions pointlessly, and applies to other transactions not at all.

But all this complexity is an expensive business. During my 25 year career as a tax lawyer, I’m pretty confident I charged at least £2m in fees for stamp duty advice9. I will modestly say it was excellent advice, and my clients were very happy with it – but multiply this across all the tax lawyers in the UK, and that’s a lot of wasted fees on a pointless tax.

Full credit to The Office of Tax Simplification, who made this kind of argument five years ago (and were ignored).

So what should the Government do?

Abolish stamp duty. It’s an easy win: a tax-simplifying, pro-investment, pro-growth policy that costs nothing and has no downside.

It’s not even technically difficult. Expand the SDRT payment/collection rules so SDRT more easily applies to paper transactions in unlisted UK shares. Tidy up the SDRT rules that rely upon stamp duty.10. There’s even an IFS paper that goes into details on how to do this.

Job done.

Is this really the stupidest tax?

No, I lied. It’s the second stupidest.

The very stupidest is bearer instrument duty – a kind of a miniature clone of stamp duty for bearer instruments. In a world where SDRT exists, bearer instrument duty is completely irrelevant and I have never seen any actually paid. For added relevance, real bearer instruments basically don’t exist anymore. The tax is in Schedule 15 Finance Act 1999 and I have not the slightest clue why it still exists.

Why haven’t both these taxes been abolished?

Hard to say. Most bad tax rules exist because someone benefits from them – perhaps HMRC, perhaps a few deserving and/or loud taxpayers. But in this case there is literally no point to stamp duty. I can only assume the calculation for HMRC is: no downside for us in keeping it in place11; work for us in repealing it.

If so, that’s the wrong calculation. Stamp duty should join the old stamping machines in graceful retirement.

Engraving of the Boston Tea Party by E. Newbury, 1789, photo by Cornischong

Footnotes

Technically this was the Townshend Act not the Stamp Act, but facts shouldn’t get in the way of a good engraving ↩︎

Post-pandemic, it’s an electronic stamping rather than physical stamping – HMRC retired their beautiful old stamping machines. ↩︎

By which I mean that, whilst not great taxes from a policy standpoint, they technically/practically work just fine. They were created because stamp duty just became too old, creaking, and easily avoided. They are “normal” taxes in that if you don’t pay them, you go to jail (maybe). ↩︎

This was created as part of a rather half-hearted and very incomplete consolidation of legislation in 1999. Believe it or not, things used to be worse ↩︎

But only “probably” – there’s a reason why I’ve have seen twenty-page opinions on at least four different words in the definition of “stock” ↩︎

What exactly does Wimpey do following the partial abolition of stamp duty by s125 FA 2003? Good luck. ↩︎

This has never, to my knowledge, happened to a large transaction, but it has created injustice on a small scale – see for example the recent Highscore case – thanks to

Nicholas Ostrowski for alerting me of this in the comments below. ↩︎The interaction between stamp duty and SDRT is another deeply fascinating area ↩︎

I am thinking something like – an average of at least £100k/year x 25 years. Obviously, it’s not money I personally received. ↩︎

There are quite a few – SDRT doesn’t have many exemptions, so “hooks in” to stamp duty exemptions – these would have to be preserved ↩︎

Because whether someone stamps a document or decided by the taxpayer – HMRC has zero compliance cost ↩︎

Comment policy

This website has benefited from some amazingly insightful comments, some of which have materially advanced our work. Comments are open, but we are really looking for comments which advance the debate – e.g. by specific criticisms, additions, or comments on the article (particularly technical tax comments, or comments from people with practical experience in the area).

Leave a Reply to Andrew Cancel reply