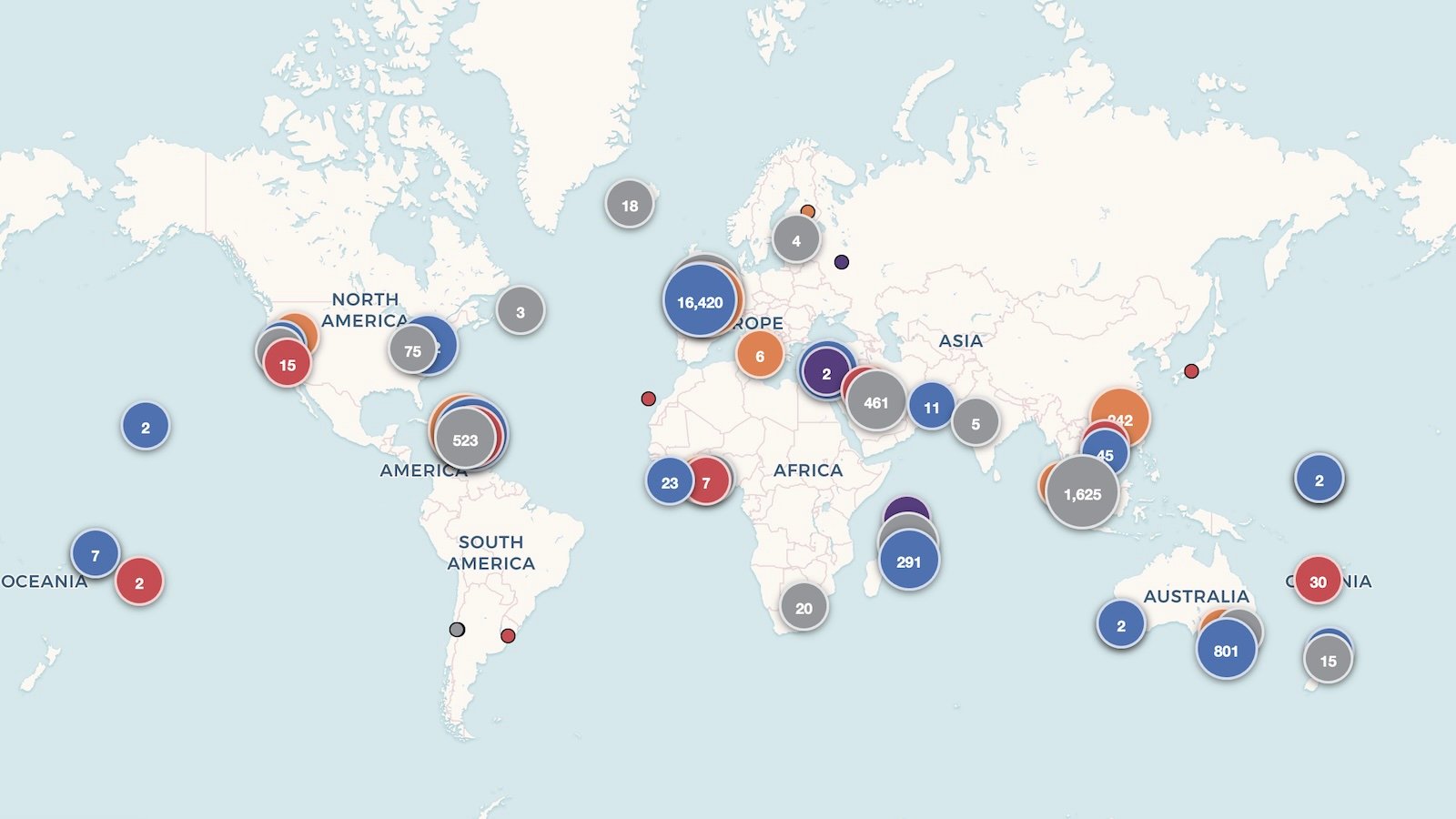

Nearly 100,000 properties in England and Wales – worth c£460bn – are owned by offshore companies. We’ve conducted an extensive analysis and created an interactive map that lets you search by property or location, and see where offshore companies are being used to hide the true ownership of the property. In 44% of cases, representing c£190bn of property, the real human owner (the “beneficial owner”) is hidden, despite the law requiring disclosure.

Some of this will be accidental, but the evidence suggests that a significant proportion is intentional. Some people are just not registering. Others are registering offshore companies as beneficial owners, rather than the individuals who really control the property. And over a fifth of all properties are held by trusts that fail to declare the true owner.

The UK’s failure to properly enforce its own rules is enabling tax evasion, money laundering, sanctions-busting and corruption. The Times has a report here.

This reports sets out our findings in detail and proposes legal and enforcement changes. We also provide open access to our map, so that you can find properties near you, or anywhere in England and Wales, owned by offshore companies that are not correctly disclosing their true ownership.

We have published our methodology in full so that interested parties can reproduce, challenge and improve our analysis.

The rules, and who’s ignoring them

In 2022, new rules required most overseas entities owning UK real estate to register with Companies House and declare who owns them – their “beneficial owners“. As many people have pointed out, the rules have been widely ignored.

We analysed data1 from the Land Registry for England and Wales, cross-referenced to Companies House and other data sources. Disappointingly, our analysis has to exclude Northern Ireland because the data isn’t available, and exclude Scotland because Registers of Scotland imposes unacceptable licensing terms. More on that here.

Our analysis puts every offshore owner in one2 of the following categories:

- Grey: We have no idea who owns 8% of the offshore companies owning English/Welsh of property. They ignored the law, and the company failed to register with Companies House.

- Red: Another 5% of offshore companies list a foreign company as their beneficial owner, hiding the real individuals controlling the company. This is generally unlawful.

- Amber: Another 10% of overseas companies are registered with Companies House, but claim they have no beneficial owner. In most cases this is not correct – it’s hiding the true owners.

- Blue: 21% of offshore companies list a beneficial owner who is just a trustee – the largest category of hidden ownership. The real beneficial owner is not identified. We believe in most cases this is unlawful.

- Green: That leaves 56% of offshore companies where the real beneficial owner is clearly being disclosed.

(If you click on the word “category” anywhere in this article, a window will pop up with the colour codes and explanations.)

In some cases the overseas property owners are taking a legally correct or at least defensible position. But in most of the cases we’ve looked at, they are not.

The register of overseas entities was last analysed in detail in Catch me if you can: Gaps in the Register of Overseas Entities, from the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy (CAGE). The overall picture of non-compliance hasn’t changed, other than that the number of overseas entities claiming to have no beneficial owner has more than doubled. 3

Explore the data, and see who’s hiding ownership near you

Here’s our interactive webapp. If you’re on mobile, or want to view full screen, click here. You will need to register and agree to terms before using. This isn’t a formality – the Land Registry requires us to retain your email address and IP address (but we do not, and technically cannot, see what you are doing with the app). More on this below.

The colour codes in the webapp reflect the colour categories.

The webapp will start a tutorial when you load it; you can run it at any time by clicking the “help” icon.

Full details below of the webapp, our methodology, its limitations, and what we think it demonstrates. Please don’t jump to assumptions about tax evasion/avoidance/illegality without reading this report in full. Locations of markers are approximate. All the information in the webapp comes from publicly available sources.

In this report:

- The rules, and who's ignoring them

- Explore the data, and see who's hiding ownership near you

- How many overseas owners fail to disclose?

- Is there a difference for different property types?

- Which countries are the worst offenders?

- Who is hiding their ownership? And why?

- Why does it matter?

- How to enforce the rules

- Limitations and methodology

How many overseas owners fail to disclose?

Here’s the proportion of property owners failing to identify the beneficial owner, broken down by the date of the transaction – reporting started in 2023, and transactions from earlier years were required to register later that year.4

The number of proprietors simply failing to register is much lower now than for the “legacy” pre-2023 registrations: 1% in 2025 compared to 9% pre-2023. That’s to be expected: if someone buys a property today then the conveyancer is likely to remind them of the registration obligation, and the lender likely to enforce it.5

However, the number of proprietors claiming to have no beneficial owner has more than doubled – 9% before 2023, 11% in 2024 but 19% in 2025. There will always be a certain proportion of proprietors that genuinely have no beneficial owner, but it’s not obvious why that would increase over time. A plausible explanation is that the lack of enforcement has emboldened people to make false statements.

And here’s our illustrative estimate of the total value of offshore-held property in each category. The total value of all offshore-owned property is c£460bn, of which c£190bn does not have an individual beneficial ownership disclosed.

If we break it down by region:

These figures are illustrative estimates, and not statistically robust – they should therefore be regarded as broad, order-of-magnitude estimates intended to indicate scale rather than precision. We take the average price paid for overseas-entity properties that had a recorded purchase price in 2023–2025, and then scale up by the number of overseas-entity properties in each category. That can’t be done for regions with very small numbers of transactions in a year (e.g. Yorkshire and Humberside had no offshore transactions between 2023 and 2025).

The estimates are based on Land Registry price-paid entries from 2023–2025 for overseas-entity properties.6 For each category we compute an average price from that sample, then multiply by the total number of properties in the category. We attempt to remove obvious duplicates caused by portfolio transactions.7, and extrapolate to the full stock of property held by overseas entities.

There are numerous reasons why this won’t statistically represent the actual value of the properties.8

Is there a difference for different property types?

We can only identify the type of property for some of the entries in the dataset but, where we can, residential property makes up about a quarter of the total. Land Registry data lets us distinguish between “detached”, “semi-detached”, “terraced”, “flat/maisonette” or (residential or non-residential) “other”9. The categorisation is not perfectly accurate and very incomplete – most residential properties are not identified at all by our current approach (and more on this below).

There is a reasonably clear trend: detached properties are almost twice as likely to be in the “red” category (company disclosed as the hidden beneficial owner, hiding the real owner):

Which countries are the worst offenders?

Jersey is by far and away the jurisdiction with the largest number of companies holding English/Welsh real estate. So it’s unsurprising that Jersey also has the largest number of companies which are hiding their ownership (you can hover over the categories to see the full data):

It’s more meaningful to look at the percentage of real estate holding companies in each country which are potentially non-compliant:

Looking at the worst offenders:

- Saudi Arabia has a small number of companies holding English/Welsh property (only 260) but 90% are non-compliant. This is disproportionately down to just a small number of proprietors. Mohammed A.Al-Faraj Corp. for Trading & Contracting owns 125 properties in the UK but isn’t registered with Companies House. Another, Takamul Economic Solutions owns 37 properties but isn’t registered. And International Capital Real Estate Company LLC owns 29 but isn’t registered. The links in this paragraph should take you directly to the relevant view in the webapp (if you are registered and logged-in).

- Denmark has only 263 companies, but 60% of them claim to have no beneficial owner – much more than any other country. This seems largely due to the properties managed by the Habro fund management group. Habro appears to have taken the position that nobody has beneficial ownership of its property companies. That’s surprising, when Habro itself declares its two joint CEOs as its beneficial owners.

- Singapore has 2,114 companies and 70% are non-compliant. That alarming statistic is, however, mostly driven by just one company – Profitable Plots PTE. It holds 1,000+ properties in the UK but hasn’t registered with Companies House, probably because its directors were jailed in Singapore for financial fraud.10 So it would be unfair to draw any wider conclusions about Singapore.

- France has a surprising number of companies that didn’t register with Companies House or claim to have no beneficial owner. It’s unclear why that is.

Who is hiding their ownership? And why?

Often ownership is hidden by mistake – people don’t understand how the rules work. But it seems that sometimes very aggressive legal interpretations are being taken.

We can illustrate this by looking at the statistics for each category in turn, and then reviewing the specific details of the most expensive properties in each category.11

Red – ownership hidden behind a foreign company

The red category properties are where there’s no individual beneficial owner declared, just a company. In most cases this is unlawful.12

We can get a sense of the varied reasons why companies are in the “red” category if we use the webapp to look at the most expensive properties in that category.

- The most expensive “red” property is part of Arundel Great Court and the Howard Hotel, 12 Temple Place, London. It was acquired for £793m on 10 October 2025 by a Jersey company, Store Holdings South Ltd. That company gives its beneficial owner as another Jersey company, Store Holdings Group Ltd. That looks like a breach of the rules – the registered beneficial owner should usually be an individual. It therefore seems likely that the true owner is being hidden; perhaps accidentally, perhaps intentionally.

- The second most valuable is Christian Dior’s £164m flagship shop at 161 and 162 New Bond Street, together acquired for £313m . It’s owned by a Luxembourg company which registers its beneficial owner as LVMH SE. The LVMH group is listed; however the parent/listed entity is LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE – so that’s the entity that should be listed as the beneficial owner. However there may be a larger error than this. 65% of the voting shares in LVMH are controlled by the Arnault family. Query if in fact Bernard Arnault should be listed as a beneficial owner.

- Next, a mews in Kensington, acquired for £194m in 2019 and owned by an Abu Dhabi company, Medco Holding Ltd. It registers its beneficial owner as International Capital Trading LLC. But this company isn’t listed; it shouldn’t be given as the beneficial owner. International Capital Trading is a bona fide business, but it’s hiding its true owner. That’s not permitted.

- City landmark 1 Poultry, acquired in 2025 for £110m. It’s owned by One Poultry Trustee No. 1 Limited and One Poultry Trustee No. 2 Limited. The first registers two further trustees as its beneficial owner; the second registers none at all. Until 2025 it was owned by Hana Alternative Asset Management; it’s now owned by unnamed Korean institutional investors. Given the wide ownership, it’s probably correct that no individual beneficial owner is registered.

- A £108m logistics unit in Chiswick is owned by two trustees in the Boreal group. Apex Group trustees are registered as beneficial owners, together with a UK company, a Jersey company and “The Asticus Foundation”. The Jersey company and the foundation don’t appear to be registrable beneficial owners; they should not have been registered. Boreal is owned by four individuals – query if they should have been listed.

- The Thames Gateway Park is also owned by the two Boreal trustees.

- Mayfair properties acquired for £94m in 2023 by a Jersey company, which registers its beneficial owner as a Bermudan company, Brookfield Wealth Solutions Ltd. That Bermudan company should not have been registered. Brookfield is widely held, and so probably the correct answer is that nobody should have been registered. The incorrect registration of the Bermuda company therefore provided more transparency than if Brookfield had followed the technically correct approach.

When we see these kinds of questionable registrations for the most valuable and highest profile companies, it suggests that non-compliance is widespread.

Grey – failed to register

The grey category properties are where the proprietor simply hasn’t registered with Companies House:

The most common reason why a company is in this category is that it broke the law and didn’t register with Companies House. There are other reasons:

- It did register, but with a typo in its name, so the app doesn’t match it.

- It changed its name, but didn’t update its Land Registry entries.13

- Our code has made a mistake and failed to match when it should have done.

Again looking at the most expensive properties:

- A mansion at 4 Grafton Street in Mayfair, bought in 2018 for £69m and one of the most expensive houses in London. It’s registered to 4 Grafton Street Limited, but no such company is registered with Companies House. The property is said to be owned by a German national. This looks like a straightforward failure to register.

- 2 Whistler Square, bought in 2022 for £52m, again one of the most expensive houses in London, is registered in the name of a Cayman company, CB2 Holding Limited. No such company is registered with Companies House.14

- Another grand house, 19 Hill Street, sold for £52m in 2008. It’s registered to a “Hill International Investments Inc” which hasn’t registered with Companies House.15

- A £49m unit at an industrial park in Enfield owned by two Jersey trustee companies, Goodman 7 Trustee 1 Limited and Goodman 7 Trustee 2 Limited. Neither is registered with Companies House.

- A £27m unit at an industrial park in Hayes owned by a Jersey company, VREP Hayes Limited. It’s not registered with Companies House.

Amber – no beneficial owner

Amber category properties are where the overseas entity says it has no beneficial owners:

Sometimes a company has no beneficial owner under the overseas entity rules. This could be the case, for example, if there’s no one person who holds more than 25% of the shares, more than 25% of the voting rights, or exercises significant influence or control over the company. Often very valuable properties genuinely have no single beneficial owner, because they’re owned and controlled by widely held entities like pension funds, private equity funds and other similar arrangements. In such a case it is correct to file with the register of overseas entities on that basis, and list the “managing officers” instead.

However we again see a pattern of questionable registrations. Take the top five most valuable amber properties:

- The £449m Blue Fin building is held by Jersey company as part of a joint venture between an Ontario pension fund and a Singaporean sovereign wealth fund. This suggests that the Government of Singapore should have been listed as a beneficial owner (there is no exemption for governments).

- BT’s old headquarters at 81 Newgate Street was acquired in 2019 by Orion Capital Managers LLP for £210m. The acquisition was via a Luxembourg company – which declares it has no beneficial owner. That is surprising given that Orion Capital Managers LLP itself declares it has three beneficial owners.

- A large plot of land in Caldecotte was acquired in 2021 by a Luxembourg company that declares it has no beneficial owner. However its directors all work for real estate investment group CBRE. If CBRE does own the property, then its listed parent CBRE, Inc, should have been listed as the beneficial owner.

- The IBM building on the South Bank was acquired for £140m in 2016 by a Jersey company16 which declares it has no beneficial owner. It’s been reported that the ultimate owner is the United Arab Emirates-based Easa Saleh Al Gurg Group. Query why members of the family controlling that group aren’t registered as beneficial owners, particularly when four of them are listed as the company’s managers.

- The W Hotel at Leicester Square (10 Wardour Street) is owned by a Jersey company, Arctic Leicester Square Ltd, which claims to have no beneficial owner. The hotel is owned by the Al Faisal Holding Company of Qatar, which appears to be controlled by Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani. It’s therefore unclear why he isn’t registered as the beneficial owner.

It’s no coincidence that three out of these five hold the real estate in Jersey – as the chart above shows, Jersey is by far the most significant offshore centre for holding UK real estate.

Our review suggests a significant number of private equity and fund management companies aren’t complying with the rules. But there are exceptions.

Blackstone are the world’s largest alternative asset management. They register their founder and CEO, Stephen Schwarzman, as the beneficial owner of over 1,000 properties. Blackstone is listed, and many businesses in this position therefore only register the listed company as the beneficial owner. But Blackstone have gone a step further, and asked: is there a person who in practice exercises significant influence over the company? The answer to that question was that there is such a person – Stephen Schwarzman. Blackstone appear to be one of a minority in the real estate industry who apply the rules properly.

Blue – only trustees declared

Blue category properties are where the only beneficial owners declared by the overseas entity are trustees. Transparency International has previously identified a widespread failure to disclose the true beneficial owner of trust structures. We believe the position is even more serious.

It is generally correct to identify trustees as beneficial owners (even where they are companies). However, in most situations where a trustee owns property, it in practice acts at the behest of another party. That makes sense – not many people would put property in trust if they wouldn’t be able to influence the trustees. And this is the key point: an individual with significant influence/control over the trustees’ activities is specifically required by the rules to be registered as the beneficial owner. However, in almost all cases, they are not. The trust industry appears to be systematically ignoring the law.

Here’s the breakdown by country:

The top five commercial properties owned by trusts:

- The Intercontinental Hotel at the O2 was acquired in 2016 by a Jersey company for £400m. The Jersey company names two trustees as its beneficial owner – and no human beneficial owner. The hotel is reported to be owned by the Arora Group, controlled by Surinder Arora. The Arora Group itself says it has no beneficial owners; it is not obvious why that is correct. If Mr Arora is the controller of the Arora Group then we expect he has significant influence over the trustees, and therefore should be named as a beneficial owner of the Jersey company.

- Land in Watford was acquired in 2019 for £250m by two Jersey companies. Both companies list only Croxley Master Trustee Limited as their beneficial owner. We expect the trust is in practice acting at the behest of the ultimate owners of the structure. A planning document suggests the ultimate owners may be the BAE Pension fund and Goldman Sachs. Pension schemes are generally exempt from beneficial ownership disclosure, but if Goldman Sachs has a 25% interest then it should have registered its listed US parent as a beneficial owner.

- Mulberry’s flagship store at 50 New Bond Street was acquired in 2021 for £198m by two Jersey trustee companies. The building is owned by the Al Khashlok Group, and the founder of the group, Dr Awn Hussein Al Khashlok is registered as a director of the companies. So it’s surprising that the Jersey companies claim to have no beneficial owner. We expect in practice they are under de facto control or, at least, significant influence by Dr Al Khashlok.

- An office building in Aldgate was acquired in 2019 for £183m by two Jersey trustee companies, which claim to have no beneficial owners. The directors are employees of Ogier, the Jersey law firm. The building appears to be really owned by Singapore investment company City Developments Limited, which is 43% owned by member of the Hong Leong group, a family owned conglomerate. The question is whether there are individuals who in practice have significant influence or control over the trustees.

- 280 Bishopsgate was acquired in 2020 for £173m by two Jersey trustees, which appear to be operated by fund administrator Langham Hall. We expect they in practice are under the de facto control and influence of the ultimate owners, CBRE Investment Management, King Street Real Estate GP, L.L.C. and Arax Properties. Arax says it’s controlled by one individual. CBRE is controlled by its listed parent CBRE, Inc. We don’t know which, if any of King Street’s partners control it. However it’s reasonably clear that CBRE and Arax’s owner should be listed as beneficial owners of the Jersey trustees.

There are some worse examples of non-compliance, where an offshore trust company claims it is its own registrable beneficial owner (something that is, needless to say, impossible). ITL Trustees Ltd and Intercontinental Trust Limited, both Mauritius companies, have acquired four valuable properties on this basis.

The top five residential properties owned by trusts:

- 9 Holland Park in London (Richard Branson’s former house) was acquired for £53m in 2016 by a BVI company. The beneficiaries are listed as two Isle of Man trustees. In practice we expect an individual has significant influence/control over the trustees’ activities and should be registered – but isn’t. So we don’t know who really owns the property.

- Just around the corner is 8 Abbotsbury Road, acquired for £21m in 2016 by a Bahamas company (which is overdue filing its Companies House return). The beneficiary is listed as a Cayman Islands trustee, again holding for an unknown person or persons.

- Apartment 2.02, 6 Horse Guards Avenue, London, was acquired for £21m in 2023 by a Cypriot company. The beneficiaries are two individuals who work for Cypriot firms, who hold as trustees for (once more) an unknown person or persons.

- Apartment 5.04, 20 Grosvenor Square, London, was acquired for £20m in 2021 by an Isle of Man company. The beneficiary is an Isle of Man trustee company, holding for (again) an unknown person or persons.

- Apartment 51, 17 Park Crescent, London, was acquired for £18m in 2021 by a Delaware LLC. The registered beneficiary is Robert Frederick Smith. The exact same ownership structure is used for other apartments in the same building, acquired for a total of £60m in 2020/21. Robert Smith appears to be the American investor (the date of birth matches, and he uses the same correspondence address for other companies that he owns). However Mr Smith is registered as a trustee, rather than owning in his own right. Someone presumably has control of the trust – and they’re not registered (it may well be Mr Smith himself).

- Flat 1, 33 Chesham Place, London was acquired for £16m in 2017 by a BVI company. The registered beneficiary is a Singapore corporate trustee holding (once again) for an unknown person or persons.

Why are trustees not complying with the law?

There are two factors here:

- Most of the commercial property above is likely owned by “Jersey property unit trusts” (JPUTs). These are legitimate investment vehicles used for commercial real estate investment.17 However these funds are typically directed/managed by an investment manager of some kind: where that investment manager has beneficial owners, they should be listed as beneficial owners of entity owning the property. They almost never are.

- The other properties will be held by private trusts of some kind, typically discretionary trusts established for financial planning and/or tax reasons. Few if any people put property into trust without a way of ensuring the trust does what they want. Typically this is achieved by the settlor sending a “letter of wishes” to the trustee which they are not legally required to follow, but in practice always do. In our view this is “significant influence” and/or de facto control, and so the settlor should be registered. However we see numerous discretionary trusts where no settlor is registered. Take, for example, Cove Estates Ltd – an Isle of Man company which holds five titles in Cornwall. Its beneficial owner is declared to be Knox House Trustees Limited, a company owned by Douglas Barrowman. However there is no entry for Barrowman or whatever other persons have significant control/influence over the trustees (and therefore over Cove Estates Ltd). That is very unlikely to be correct.

We can get a sense of how widespread this is by looking at the number of properties held by the big professional trustees, and counting how mnay times we see a true individual beneficial owner disclosed, and how many times we don’t.

Our analysis shows 201 professional trustees registered as beneficial owners of UK properties. Of those, 181 have never once disclosed a true beneficial owner. This chart shows the other 20 trustees, who’ve disclosed a true beneficial owner at least once, and the percentage of their properties where full disclosure was made:

Looking at the trustees that appear to top this chart, and therefore be the most compliant:

- JTC Trustees appears to have a high level of correct reporting because their Companies House entry discloses they are held by JTC plc, a listed company. That is correct disclosure of their own position; however they don’t appear to ever disclose individuals as beneficial owners.

- Line Trust Corporation Limited appears to have a high level of correct reporting because their properties in London’s East End often show a Gibraltar individual, Douglas Ryan, as a beneficial owner.

- Chancery Trustees and Oak Trust (Guernsey) Limited seem to genuinely disclose individual beneficial owners in a material number of cases, making them unusual in the trust market.

- Standard Bank Offshore Trust Company Jersey Ltd discloses two individuals as beneficial owners, but they appear to be employees of Standard Bank. The true beneficial owners are not disclosed, so far as we can see.

Bad as this all is, our analysis likely under-estimates the secrecy which is being employed by trust companies. There’s evidence that the trust companies are using UK corporate beneficiaries to “block” the beneficial ownership rules. Take an example: this land in Grimsby. It’s owned by two Apex Jersey trustee companies. The beneficial owner is stated to be Apex Consolidation Entity Ltd, a UK company which claims it has no beneficial owners itself. What’s really happening is (we expect) that the land is under the de facto control of the settlor of the trust under a letter of wishes or similar arrangement – the settlor should be registered as a beneficial owner (but isn’t). However because there’s a UK incorporated company declared as beneficiary, our webapp assumes all is well and puts the property in our “green” category.

Is there a “trust loophole”?

A key reason why there’s so little disclosure of the true ownership of these trusts is the widespread belief – almost universal in the world of professional trustees – that there’s a significant loophole in the rules.

The “loophole” looks like this:

- Someone – let’s say Vladimir Putin – wishes to hide their ownership of a valuable house in London.

- Mr Putin arranges for the house to be acquired by Offshore Trustees Ltd on his behalf.

- Offshore Trustees Ltd is a professional trust company in Jersey owned by individuals unrelated to Mr Putin. Like many such companies, it holds hundreds of properties for hundreds of different people.

- Offshore Trustees Ltd holds the property on discretionary trust for Mr Putin, in practice always acting as he requests (under a “letter of wishes”).

Or to put it in a structure diagram:

(Legal Owner)

Registered as beneficial owner

On Register

(Legal Owner)

Registered as beneficial owner

On Register

Significant influence

over ownership of house

Offshore Trustees Ltd claims it’s technically correct under current law for the owners of Offshore Trustees Ltd to register as the beneficial owners of Offshore Trustees Ltd, and for there to be no entry for Vladimir Putin, even though he’s the one controlling the property. That is the position the corporate trustees we spoke to are taking. The justification is that Mr Putin has no significant influence or control over Offshore Trustees Ltd as a whole, only over a small part of its activities (its ownership of his house).

This, however, completely undermines the point of the register. 18

It is also at odds with the wording of the legislation. Mr Putin’s has his own trust – the only property in the trust is his house (he’s unlikely to be “sharing” a trust with Offshore Trustees Ltd’s other clients, and there would be legal and tax complications if he did). Mr Putin has significant influence or control over the “activities of the trust” even though he doesn’t have significant influence/control over Offshore Trustees Ltd itself. The rules specifically make that distinction, and look at the activities of the trust. This means Mr Putin should be registered as a beneficial owner. We understand the Department for Business and Trade believes this is the correct approach, and therefore the “loophole” does not exist. We agree – that’s the answer consistent with both the spirit and letter of the legislation. However, both our discussions and the evidence above suggest that the trust industry does not agree.

It would be helpful if the Department of Business and Trade could make this point explicit in the guidance. If not, the law should change to put the point beyond doubt.19

Why does it matter?

There is nothing inherently suspicious about a foreign entity holding UK real estate. For example, if you zoom into Canary Wharf, you’ll see Citibank’s UK headquarters, which is held (unsurprisingly) by Citibank. If a foreign person is investing in UK real estate then it is only natural it holds through a foreign company, and UK tax rules will now tax it in broadly the same manner as a UK company – so there is no avoidance here.20

Some people have presented the raw numbers of overseas real estate holders as some kind of problem – that is in our view wrong and misleading.

However it is absolutely a problem when the true ownership is hidden.

In most of the colour category examples above we were able to establish the true ownerships of the largest properties. That’s because they were large properties and their acquisition was often publicised. For smaller properties, and residential properties, this is usually not possible. So the lack of correct disclosure, which was a slight headache for £200m properties, becomes a significant barrier for (say) £10m properties. This creates a series of problems:

Tax. Where a foreign individual owns a “property rich company” holding UK real estate, and sells that company, he or she will in most cases be liable for UK capital gains tax. But if the individual is never disclosed as the beneficial owner, HMRC have no way to know if that sale took place. Each grey, red and blue company represents potential UK lost tax. And of course the owner may also be failing to pay foreign taxes – property is particularly well suited to tax evasion when beneficial ownership can be concealed.

Sanctions. Our app displays (in purple) properties owned by sanctioned individuals and entities. The number of such properties is extremely small – 38. We don’t believe this is correct. We spoke to sanctions experts who expected there would be hundreds or even thousands of UK properties owned by sanctioned Russians – but because they hold via red, grey and blue category companies, we don’t know who they are, and we don’t know what they hold.

Money laundering and corruption. UK property is an excellent safe way to park large amounts of money if you’ve stolen it or are looking to hide it – and the Government’s economic crime plan says that £100 billion laundered through and within the UK. The register of overseas entities should prevent that – but all its flaws mean that in practice it doesn’t.

How to enforce the rules

People are going to continue to ignore the overseas entity rules until there are clear consequences for breach. Only fourteen fines were collected in the two years since the rules were introduced (our of 444 issued).

We would suggest that DBT consider the following steps as part of its next review:

- The Department of Business and Trade and/or Companies House should issue a notice warning the trust industry about the widespread failure to register true beneficial owners.

- Companies House should start using their civil penalty powers at scale, sending formal notices to proprietors with questionable (or absent) registrations,21 and requiring further information. If there is no satisfactory response, Companies House can now place a warning notice on the Companies House register and a restriction on the Land Registry title (preventing mortgages being obtained or the property being sold).

- Where there are good grounds to believe the law has been broken (for example a simple lack of registration, or inadequate response to the formal information notice), Companies House should send formal warning notices and then, if ignored, issue penalty notices (which scale with property value).

- This would likely result in many thousands or penalties being issued. History suggests most would be ignored. We’d suggest expanding Companies House existing powers so that a restriction can be placed on title where penalties are not paid.

- Companies House should select test cases, with particularly clear facts, for prosecution. The officers of a company commit a criminal offence if it fails to register with the register of overseas entities – with up to two years’ imprisonment and an unlimited fine. About 8% of all properties are in this category. We’re not aware of any prosecutions. It’s rational for people to pay little attention to these rules unless there are clear sanctions for those that intentionally or negligently fail to comply.

It’s always been the case that rules that aren’t enforced may as well not exist.

Limitations and methodology

The code that analysed the Companies House and Land Registry data, and then created the webapp, can be found on our GitHub here. It’s all open source, and everyone is welcome to use/copy/adapt the code and the data, provided they fairly attribute it to us.

The basic approach is as follows:

- Go through the Land Registry’s dataset of overseas companies that own property in England and Wales (“OCOD”).

- The property type isn’t listed on the overseas company dataset. We therefore cross-check against the Land Registry’s separate price paid dataset, which includes a not-very-reliable flag for the type of property. The price paid dataset doesn’t include the title number, so we cross-check the two datasets first using the price paid and the postcode, and then using fuzzy matching on the address. This is far from completely reliable, and even then only matches a small proportion of the overall properties – properties sold since 1999, with a “price paid”, and where the correct “property type” box was ticked. Further work could be done to improve this.

- Use the Companies House API to search for each owner (registered proprietor) on the register of overseas entities. This is complicated by numerous inconsistencies in formatting, spelling, etc.

- If the proprietor can be found, then use Companies House’s API again, to identify its beneficial owners, their category (UK company, offshore company, individual, trustee) and the nature of their ownership.

- Geolocate the property, the company, the registered proprietors and their beneficial owners, sanity-checking to catch obvious mismatches. Geolocations are by postcode and Google’s api and therefore will be approximate.

- Categorise each owner, and each property, into the colour categories above: green only when every proprietor has at least one individual non‑trustee controller; amber where there’s no registered beneficial owner, grey where we can’t find the named proprietor on Companies House, blue where all the registered beneficial owners are trustees, and red where the only registered beneficial owners are offshore corporates (excluding those we’ve found on databases of listed companies).

This is not straightforward due to the poor quality of the data:

- There are many wrong and misspelt company names. Sometimes the errors are small, e.g. Al Jameel Holding Ltd is listed as the proprietor of fourteen properties, but there’s no such company at Companies House. The actual owner is probably Al Jameel Holdings Ltd (with “Holdings” in plural). We show this as an unregistered owner (which is technically correct).

- Minor errors abound. Even major companies like Hutchison Ports have typographical errors in their entries – writing “Je49wg” instead of “Jersey”. That complicates the geolocation.

- Where a company is in the Land Registry data but not on Companies House then we check for minor variations; if we can’t find them, we mark it as unregistered. It’s hard to know where the boundary lies between typographical error and failure to register. For example, one overseas entity on the register is “Bontex & Luis Inc”. There is no such company. There is a “Bontex & Luis Inc Ltd“, but that’s a UK company not an overseas entity (so this is unlikely to be a mere typo). We’ve marked Bontex & Luis Inc as unregistered.

- In some cases a company’s name has changed but the register wasn’t updated. We try to catch this.

- Locating the address isn’t easy. Where there’s a correct postcode we can easily use the ONS postcode list. About a quarter of the approximately 100,000 properties on the register list an incorrect postcode, or no postcode. In theory it should be easy to look up the location with the land registry title number, but that requires an individual land registry search which is cost-prohibitive (they’re £7 each).

- There are then obviously wrong addresses – e.g. overseas entities giving their address as Guernsey followed by a London postcode.

The detail is set out in the code published on our GitHub. Our approach necessarily involved a series of judgment calls, and errors are inevitable. Nobody should make any conclusions about particular companies without checking them carefully by hand.

If you do identify any errors then please get in touch. We’d be delighted if others find our code useful, but unfortunately we’re not able to provide any support.

Shadow properties

There’s a category of properties not visible on our webapp – “shadow properties” – overseas entities that aren’t on the Land Registry’s list of overseas entities owning property in England and Wales.

There are two types of shadow properties.

The first is where companies have been placed on the Land Registry’s list of UK companies owning property in England and Wales rather than the list of overseas companies. We have undertaken an initial analysis, and found some entities that should be on the overseas entity list:

- Cases where the stated entity type suggests it’s a foreign company. There are fourteen entities with names ending in “Inc”, ten ending in “SA”, one “NV”, nine in “Corporation” and ten “PTE Ltd”. Many of these are likely innocent errors, but one entry looks potentially fraudulent – an “Apple International SA” owning small plots of land in Durham.

- Cases where the given company name says explicitly it’s a foreign company – for example one entry on the register is “CPS Investment Management Limited (incorporated in British Virgin Islands)”.

- Financial institutions whose name suggests they are foreign entities: Royal Bank of Canada Trust Company (Jersey) Limited, HSBC Trustee (Singapore) Limited, Kleinwort Benson (Guernsey) Trustees Limited.

- Foreign governments: the Hellenic Republic and the Federal Government of the United Arab Emirates. The Hellenic Republic entry shows it owning the Greek Embassy – so this is clearly the real Hellenic Republic which an administrative error misclassified as a UK company. The UAE is listed as owning a modest detached house in Pevensey – we don’t know if that’s misclassification or fraud (i.e. someone using the UAE’s name).

There are other data problems: there are at least thirteen individuals on the list of UK companies.

It’s likely that the initial error in these cases was made by the company/individual buying the property (or their conveyancer).22. The Land Registry says they don’t validate company numbers (which is fair enough), but it appears that they also don’t undertake basic checks of the list.

The above errors are not hugely significant, and probably responsible for no more than 100 proprietors being missing from our analysis.

The second category is more mysterious.

Land Registry records show that a company called Uart International SA acquired a £12m house in Oxfordshire in 2025. However it’s not on the Land Registry’s list of overseas entities holding English/Welsh real estate (or the Land Registry’s list of UK companies). One possibility is that this is an accident (e.g. the company accidentally declared it was an individual). Another is some kind of Land Registry data error.

Uart International SA did comply with the register of overseas entities rules – it registered with Companies House as a Panamanian company. It appears to be concealing its true beneficial owner – probably unlawfully, it declares a BVI company as its beneficial owner (plus a Cyprus trustee company).23

We don’t know if the case of Uart International SA is a strange one-off error, or the sign of a more systemic problem. It’s not possible to conduct reverse-searches of the Land Registry, so at present we have no way to examine this question further. The Land Registry, on the other hand, could easily search its register for obvious foreign entity names which have not been correctly registered – we expect this would take little more than a simple database query.

Scotland and Northern Ireland

Our analysis is limited to England and Wales for the simple reason that HM Land Registry makes data for England and Wales available (but see below), but its Scottish and Northern Irish equivalents do not.

There is a Scottish register kept by Registers of Scotland but, for reasons we do not understand, Registers of Scotland told us they prohibit any use that (like this one) makes the full data available for public viewing, and they also require us to have “appropriate security and monitoring controls in place in relation to the data you provide online to ensure customers use it appropriately”. There’s also a requirement that we don’t use the data in any way that could affect Registers of Scotland’s reputation. We can’t agree to this.

We aren’t aware of any arrangements for publishing the Northern Ireland register.

This all has consequences. It’s hard enough to see who is the ultimate owner of UK property, given the widespread non-compliance. But with Scottish property we can’t even start. So, for example, Bagshaw Limited is an Isle of Man company owning property in Glasgow and which was reported to be ultimately owned by Douglas Barrowman and Michelle Mone. There is, however, no easy way to investigate that from publicly available sources.24

HM Land Registry’s impossible licensing terms

The only reason this webapp exists is that The HM Land Registry makes the dataset (of overseas companies owning property in England and Wales) freely available. This is fantastic. However there’s a problem: the Land Registry’s licence contains provisions that require us to collect the name, email address and IP address of all users, and provide them to the Land Registry if for their “audit” purposes:

This is unacceptable from a privacy standpoint, and in the view of the GDPR specialists we spoke to, clearly contrary to GDPR. We’ve no idea why a public body would act in this way.

It also makes no sense. Anyone can go to numerous websites that show every property in the UK, its precise address and estimated current price. Or anyone wanting the overseas entity data can download the underlying Land Registry data directly, as one large spreadsheet, by entering a name verified with a credit card (real or stolen). If you’re a fraudster who wants to quickly identify valuable properties then that spreadsheet is much more useful than our webapp. There is in practice no way to tie a particular fraudulent use of the data with a particular download.

By contrast, our webapp is an awkward tool for criminals, and a convenient tool for journalists, researchers and members of the public. The idea that users of this webapp are a particular fraud risk, justifying routine collection of personal data and handing it over on demand, is indefensible.

We have told HM Land Registry that we will comply with the licence terms so far as they are lawful. UK GDPR overrides any contractual term that would require unlawful processing of personal data. In particular:

- We will not provide HM Land Registry with users’ personal data for general “audit” purposes. If HM Land Registry wants to audit compliance, we can provide appropriately redacted records (including no personal information.

- We accept that HM Land Registry has a legitimate interest in preventing or detecting crime. But that does not justify handing over everyone’s personal data. We will only disclose personal data where HM Land Registry makes a specific, particularised request and it is “necessary” and therefore lawful under GDPR. It is not clear to us how such a request would ever be necessary and therefore lawful.25

That is why registration is required. We are collecting the minimum personal data needed to run the service and to meet the licence requirements so far as we lawfully can. That includes collecting names, email addresses and IP addresses, but we will absolutely not pass that information to HM Land Registry without a very convincing, and lawful, rationale. We will not pass that information to any other party without a court order (which we would resist). We explain this in our Privacy Notice, and we will be transparent about any request for access we receive.

We do not track how users are using the webapp – and technically we cannot, because the webapp runs entirely locally on the user’s device. So we know if a particular user accessed the webapp at a particular time, and the IP address they accessed it from (unless they are using a proxy or VPN), but we do not know anything else.

We have explained the above to HM Land Registry and suggested they reconsider their licensing terms. They have asserted that their terms are “fair” and “lawful” but haven’t been able to explain why providing them with complete data on all users, their contact details and IP addresses for “audit” purposes is “necessary”.

We don’t know why a public authority is trying to enforce oppressive data collection terms, and we are referring the matter to the Information Commissioner.

You are free to use the map for any purpose – if you find something interesting then we’d be grateful if you could credit us, but you don’t have to.

Thanks to T, C, O and L for most of the analysis and coding, to K1 for specialist ROE input, and to B and A for their GDPR expertise. Thanks to K2 for their expert review. The original concept and coding of our 2023 map was by M. With thanks to CAGE and Transparency International for all their previous work in this area.

Many thanks to The Times and David Byers.

Underlying information produced by HM Land Registry © Crown copyright 2025 and used under licence.

Footnotes

This is an updated and greatly expanded version of a project we published in January 2024. There was an earlier Private Eye analysis and map published in 2015, before the Register of Overseas Entities was created. ↩︎

Sometimes more than one category apply, for example there is a trust owner and an owner which is a (non-trust) corporate. Our code prioritises the most “serious” category, being broadly red -> grey-> amber -> blue ↩︎

CAGE converted roughly 90,000 titles into an estimated 152,000 properties using a title-to-property conversion, which is a different unit of measurement; they also use somewhat different categories to us, so our counts are not directly comparable with theirs. ↩︎

Note that this is a count of overseas entities/proprietors not titles/properties. ↩︎

Because otherwise their security will be prejudiced; property owned by an overseas entity that isn’t registered can’t be sold. ↩︎

We only use data from 2023, 2024 and 2025 because it’s hard to account for asset price inflation in earlier years. ↩︎

For two reasons. First, if one buyer acquires multiple properties in the same transaction then often each title shows the overall purchase price. So a simple average would massively over-estimate the price paid. Second, in other portfolio cases there could be a transaction that is commercially for £1bn, but split with different values across different properties. We treat this as one transaction. Our deduplication is heuristic and may both miss duplicates and remove genuine distinct purchases, affecting the average price and therefore the scaled total. ↩︎

Most significantly the underlying data is affected by selection bias: high-value commercial and residential property is often transferred via corporate share sales rather than registered land transfers, meaning many valuable assets never appear with a contemporary price on the Land Registry at all. Whilst sales are supposed to always include the price paid, for some very valuable properties people (unlawfully) fail to do so. These factors would tend to make our estimate too low. On the other hand, the result is susceptible to a few very high value transactions – and this would tend to make our estimate too high (but excluding those transactions would create probably a larger source of error). Conversely, the subset of transactions that do appear in recent years may not be representative of the historic stock as a whole (some very valuable property is never sold; some property with a very low value is never sold) – we don’t know what the overall impact of this factor would be. An additional two factors potentially under-estimate value: we are ignoring inflation, and we’re ignoring post-acquisition improvement of properties. ↩︎

A mixture of land, commercial property, mixed use, and non-standard dwellings ↩︎

They sold worthless land in the UK to investors (predominantly in Asia) and claimed it had development value. However it appears they were jailed for stealing from investors in another project to support the land business. ↩︎

Although note that the Land Registry only required the price to be registered in 2000, so any properties acquired before then won’t show up in the “most expensive” list. ↩︎

There are exceptions for Governments and public authorities, UK companies, companies whose shares are listed on a regulated market in the UK, EU or certain other jurisdictions, and corporate trustees. All of these are registrable beneficial owners that should properly be on the register (although that doesn’t prevent any individuals who also have significant influence/control also being on the register). We’ve done our best to screen those out, so the red properties are in most cases companies that should not be on the register. However there will inevitably be errors. Please look at any specific case in detail before jumping to conclusions. ↩︎

There are some surprising examples. Barclays Wealth Trustees (Jersey) Limited owns five properties but isn’t registered with Companies House. The reason seems to be that it changed its name to Zedra Trustees (Jersey) Limited but didn’t update the Land Registry. ↩︎

The companies with similar names are all UK companies. ↩︎

There is a “Hill Investments International Limited” but that seems too different to be a typo registration. ↩︎

For unknown reasons, the original Companies House registration in 2022 said the company was incorporated in Gibraltar (even though the land registry entry said it was a Jersey company). This was then updated to Jersey in 2024. ↩︎

The benefit of a JPUT is that investors can own property through a “tax transparent” fund – meaning investors are taxed directly on rental income, rather than there being two levels of taxation, but without the stamp duty land tax complications that would follow from using a partnership or LLP. ↩︎

There was a change of law last year to require simple trusts/nominee arrangements to be registered – but it doesn’t apply to settlements/discretionary trusts. There are also separate rules requiring overseas entities to register information regarding trusts and their settlors and beneficiaries with Companies House. This information is not made public. In principle it can obtained by applications to Companies House, but in practice it is difficult or impossible to make such applications, because you have to know the name of the trust (information that usually only the parties involved will possess). ↩︎

There is a further, deeper, problem. Even if Vladimir Putin was registered as a beneficial owner, he’d be registered as a beneficial owner of the trust company. We wouldn’t have anything tying him to his actual house. Fixing this requires more significant changes to the design of the overseas entity regime. ↩︎

The position used to be different. Foreign companies holding UK real estate have always been subject to UK tax on their rental income, but gains used to be exempt. That changed in 2015 for residential real estate and in 2017 for non-residential real estate. There also used to be an inheritance tax benefit for non-domiciled individuals of holding UK real estate through a foreign company; that went in 2017. There is a brief summary of some of these issues here. It is therefore often the case that UK land is held offshore for historic tax avoidance reasons that no longer apply, but extracting the land from the current entity owning it is more cost/hassle than it’s worth. ↩︎

We anticipate that Companies House and HM Land Registry, with their enhanced data access, could greatly improve on the approach we adopted for this report. ↩︎

i.e. they completed the wrong box in section 6 of the Land Registry form. ↩︎

Because it’s not on the Land Registry entity lists, it’s impossible to tie the company to the Oxfordshire property without (as we did) looking at the individual Land Registry title. ↩︎

The Scottish position is further complicated by the way Scottish land law works. There is a partial map of Scottish rural land ownership here, but we’re not aware of any equivalent for urban areas. ↩︎

i.e. because if a crime was committed using Land Registry data, how would HM Land Registry suspect one of our users, as opposed to anyone else who downloaded the dataset? And how would our user data, merely consisting of times, email addresses and IPs, enable identification of a suspect? ↩︎

![32 [F1 General false statement offence] [F1 False statements: basic offence]

[F' (1) It is an offence for a person, without reasonable excuse, to—

(a) deliver or cause to be delivered to the registrar for the purposes of this Part any document that is misleading,

false or deceptive in a material particular, or

(b) make to the registrar, for the purposes of this Part, any statement that is misleading, false or deceptive in a

material particular.](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Screenshot-2023-12-28-at-11.41.07-640x118.png)

Leave a Reply to Bubblegum Cancel reply