Last Tuesday, I awoke to an email from the High Court, rejecting an attempt to silence me with an interim injunction. This came as a surprise, because I’d no idea anyone had applied for an injunction.

This was an “on notice” injunction application – but I had received no notice. What kind of lawyer would do that?

The “leading tax barrister in the country”

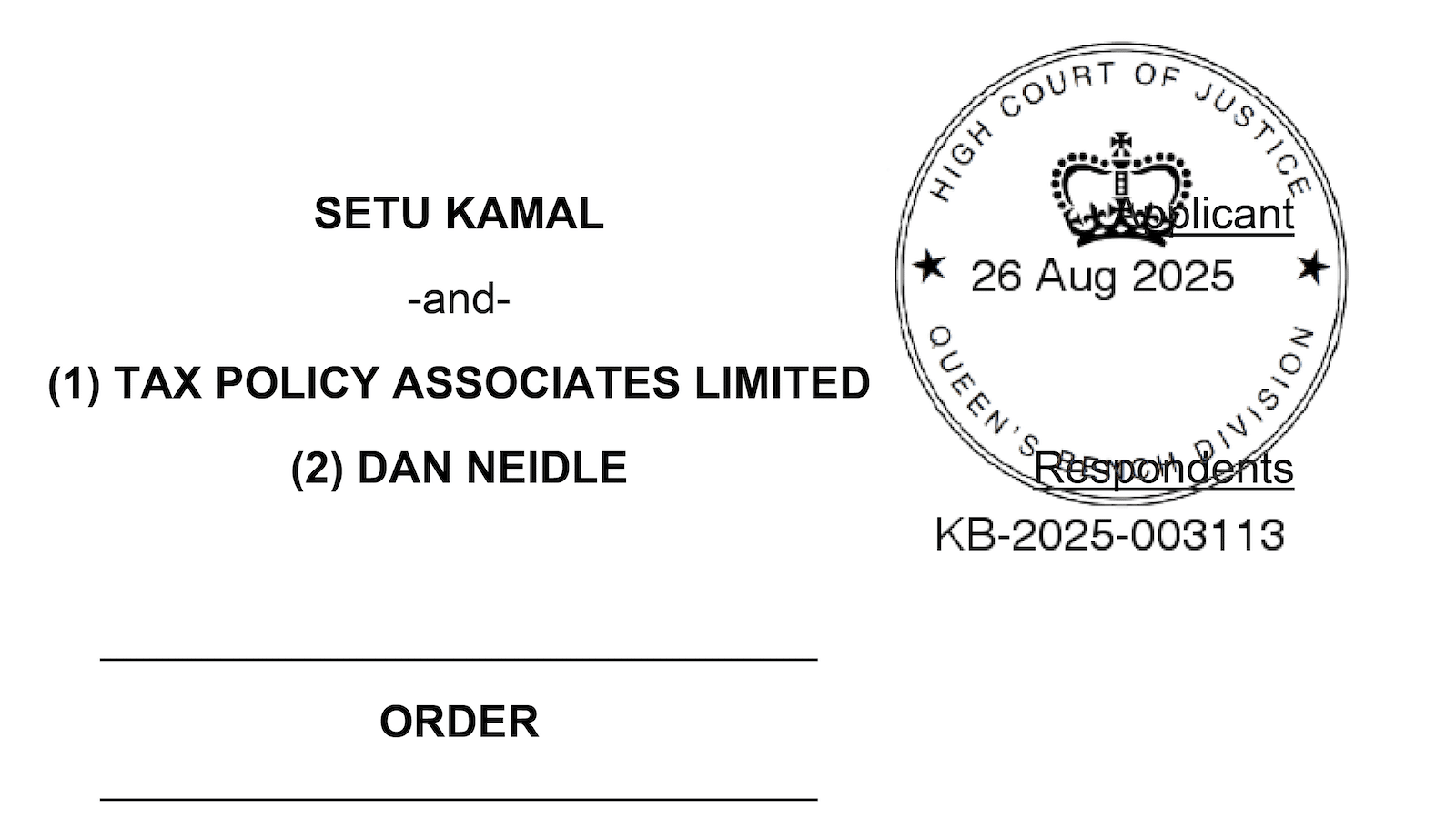

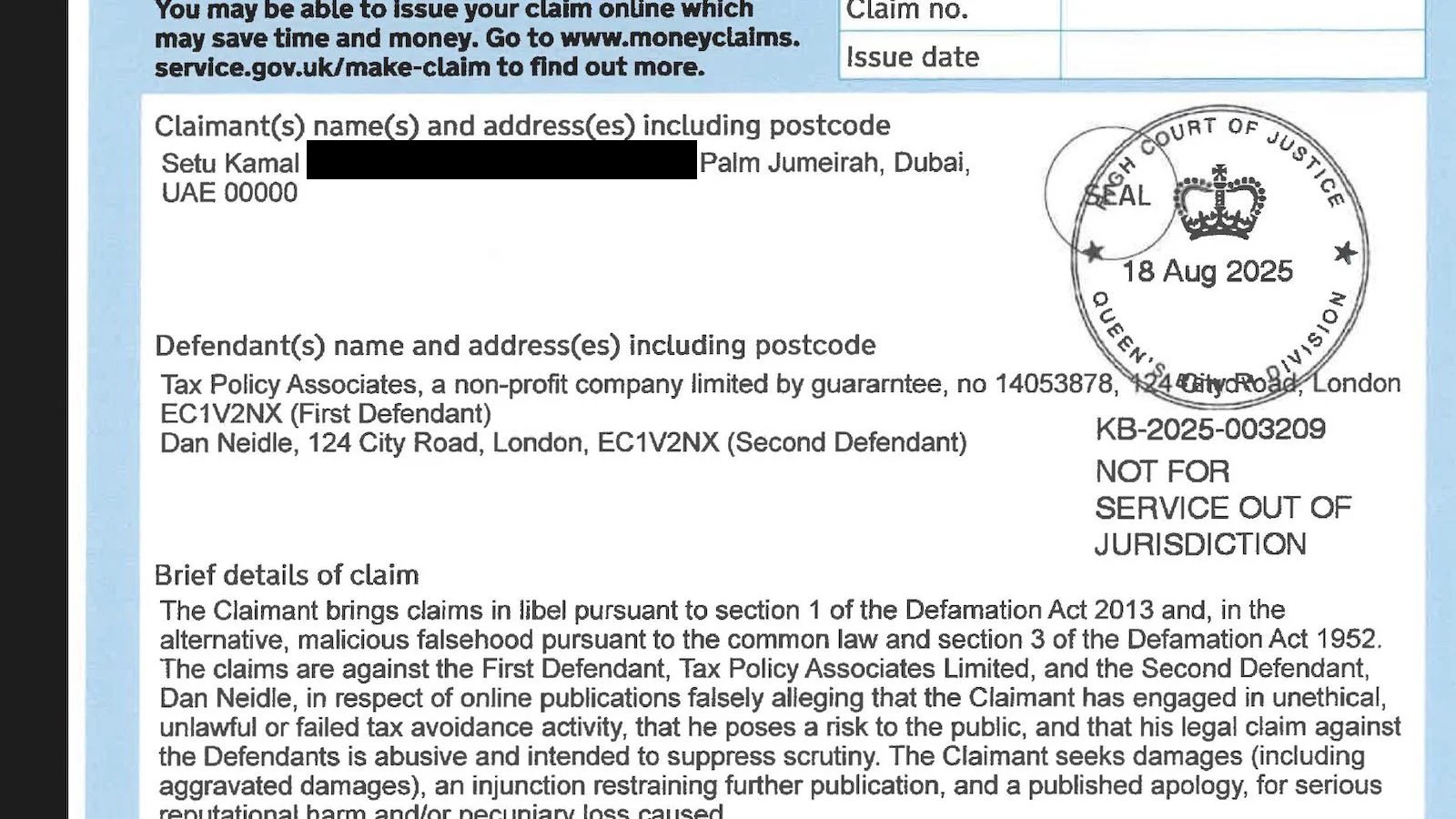

The injunction application was brought by a tax barrister called Setu Kamal.1

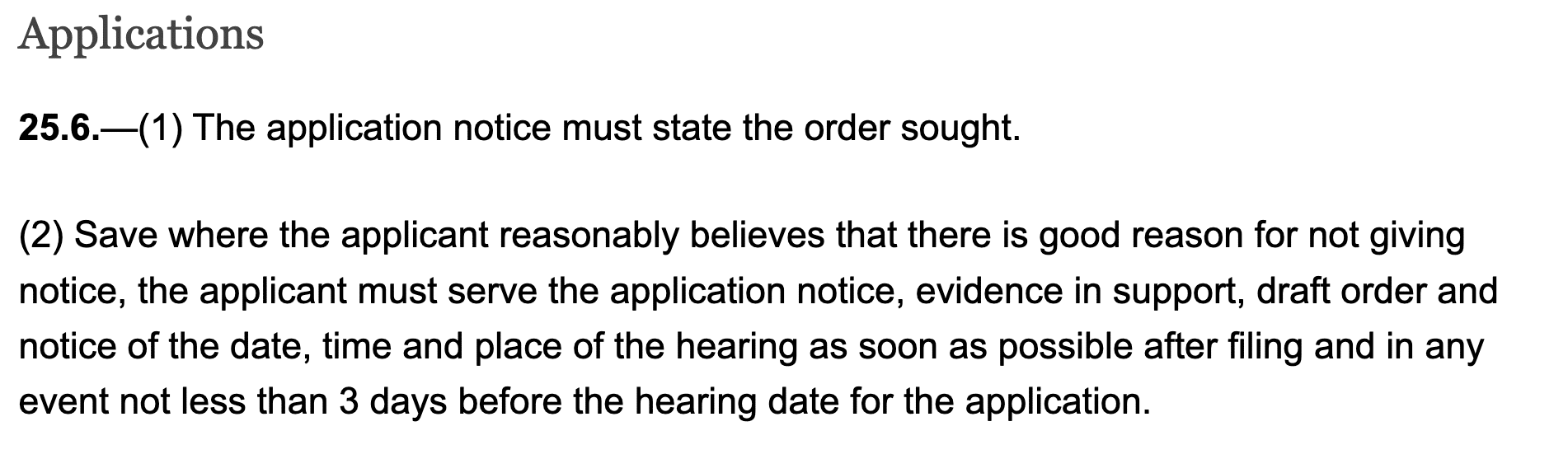

Mr Kamal is unhappy with our report about him and Arka Wealth, the tax avoidance scheme promoter he worked with and helped promote.2 Mr Kamal claims our report costs him £1m every year in lost business. Back in May, Mr Kamal threatened to sue me unless I published my “sincere belief” that he is “the leading barrister in the field of taxation in the country”:

![In light of the reputational harm caused, which easily passes the threshold of “serious harm” under Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2019] UKSC 27, I require the following steps to be taken within 7 days:

Publication of a clear and public confirmation of your sincere belief that I am the leading barrister in the field of taxation in the country, as previously stated, and a sincere apology for your misleading and disparaging remarks;

Retraction or substantial amendment of the headline and body of the article so as to remove the defamatory implications it currently conveys;

Publication in full of my letter to the Information Commissioner, together with acknowledgment of the outcome of the BSB investigation;

Written confirmation that you shall apply higher editorial standards in the future, and that no further false or misleading references to any persons will be made in your publications;

Undertaking to make the following payment: you shall undertake to pay 80% of any amounts which my regular or historic clients represent to you, in writing, as amounts they would have paid to me under an engagement with me, but did not do so because of your publications.

Should you fail to take these steps, I will proceed without further notice to pursue all remedies available to me, including injunctive relief, damages, and costs.

Yours sincerely,

Setu Kamal](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/image-2-2000x1102.png)

I did not do as asked. Mr Kamal is not, in fact, the leading tax barrister in the country.

Mr Kamal’s practice

On 4 September 2025, HMRC named Mr Kamal as responsible for promoting and designing tax avoidance arrangements, saying he has created contract templates that are “essential to how these arrangements operate”.

It’s HMRC’s view that these schemes do not work – I agree, and I believe most advisers do too.

This is an unusual step by HMRC, and the first time a practising lawyer has been named as a tax avoidance scheme promoter.

The “on notice” application, without notice

On 13 August, Mr Kamal asked my solicitors if they’d accept service of a defamation claim; they said they would. Six days later, without telling us, he applied for an interim injunction (representing himself, without a lawyer).

Here’s Mr Kamal’s application to the court:3

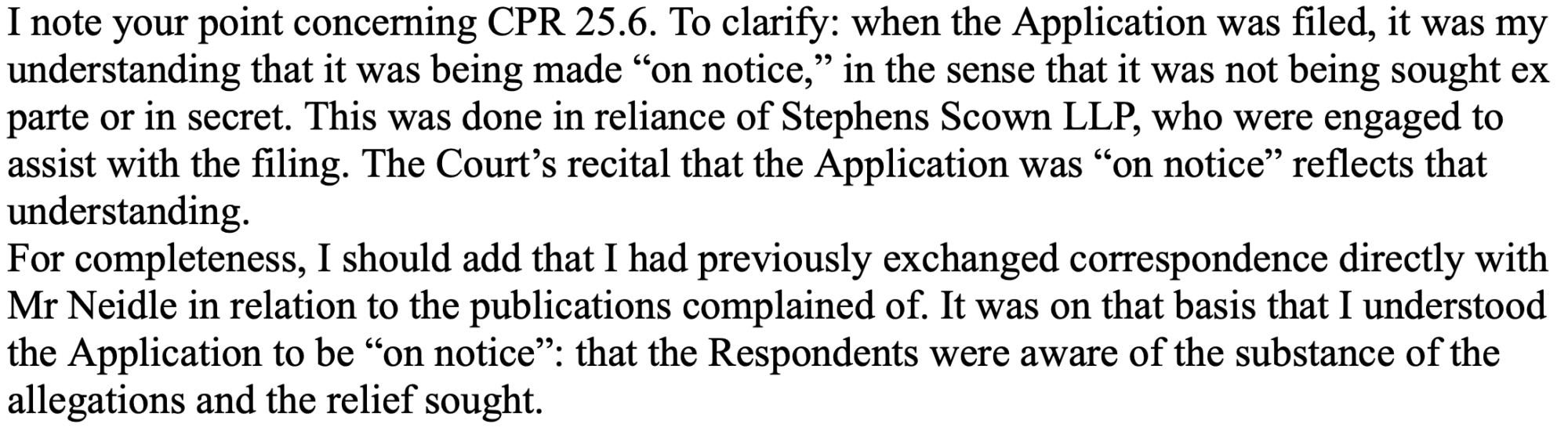

This was an “on notice” application. This means that, as is fairly obvious from the title, the other side has to be given notice of the application.4 The Civil Procedure Rules couldn’t be clearer, and even a simple Google search reveals the answer in seconds:

After I received the court order, my solicitors wrote to Mr Kamal asking what he thought he was doing (at that point we hadn’t seen the application, and didn’t really know what was going on).

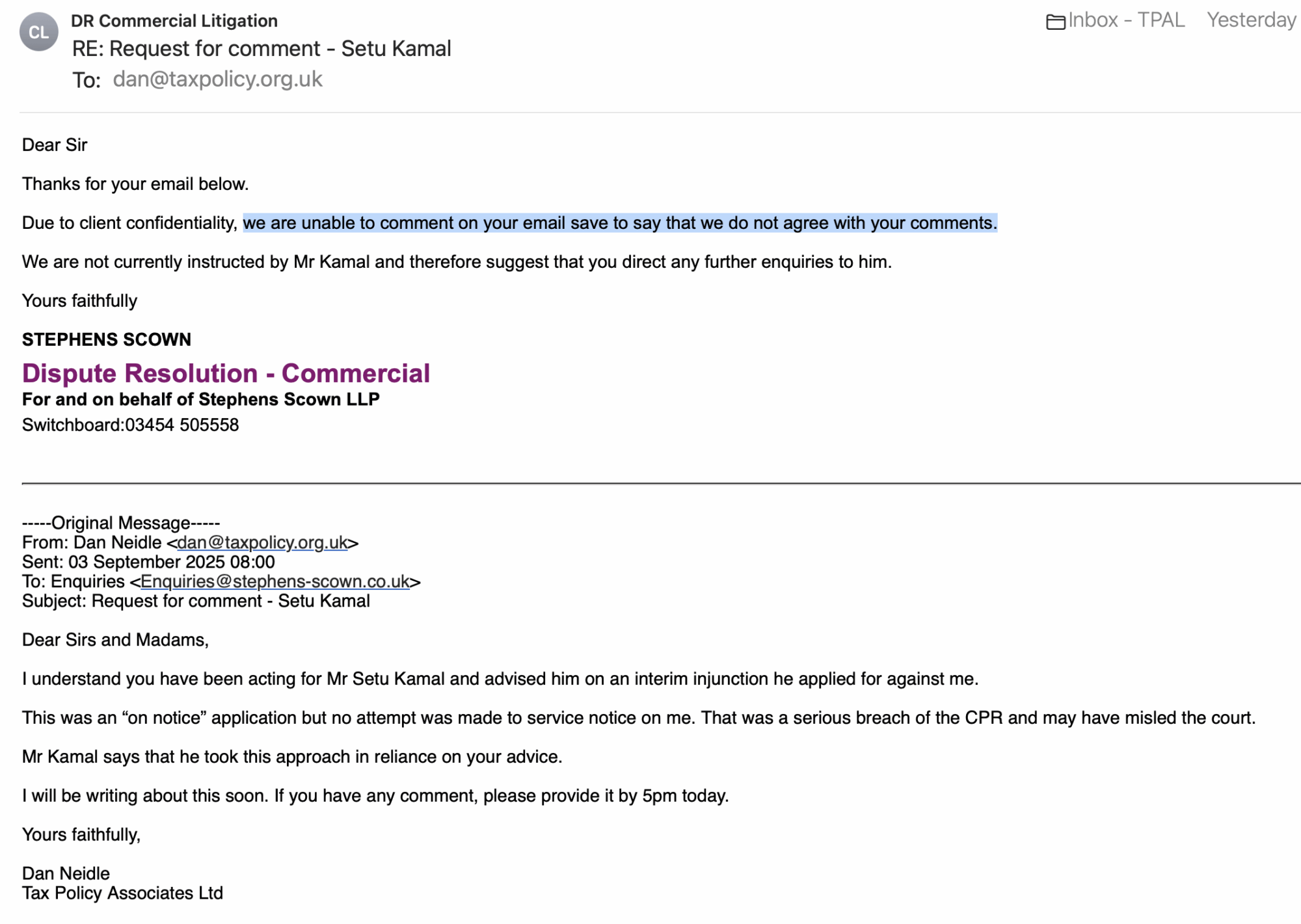

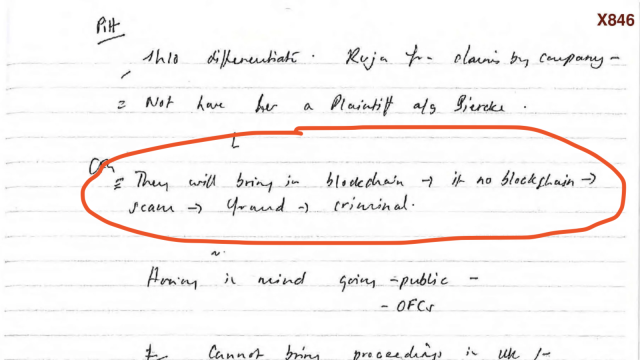

Mr Kamal’s reply was that he simply had no idea that an “on notice” injunction required notice:

This is word salad. A barrister shouldn’t be relying on a solicitor to understand a simple CPR point. But I’m going to take Mr Kamal at his word, and accept that this was not a malicious attempt to mislead the court and obtain an injunction on the sly, but merely incompetence.

I asked Stephens Scown about this and received a slightly mysterious reply, which may (or may not) be a denial that they advised Mr Kamal that no notice was required:

The defective application

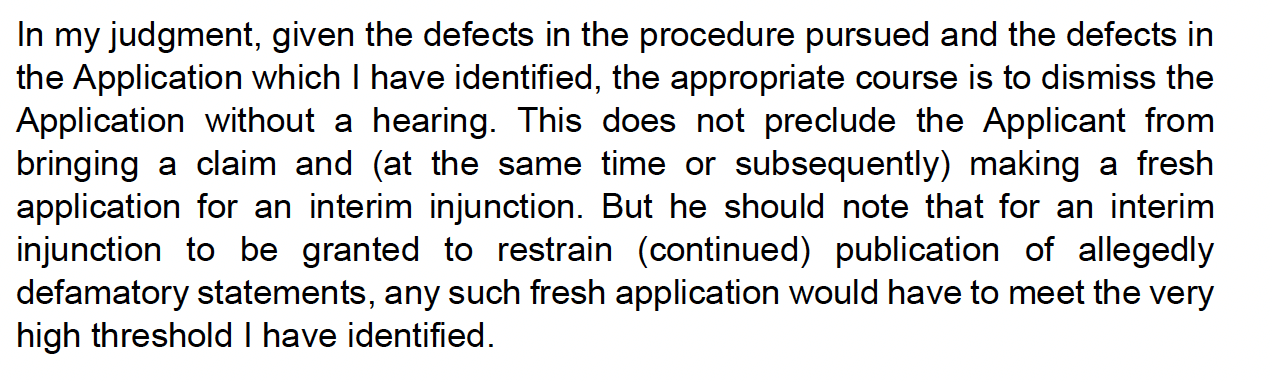

Incompetence is the most plausible explanation, because the entire injunction application was defective.

You can’t apply for an interim injunction before issuing proceedings, unless the matter is urgent, or an interim injunction is “otherwise desirable in the interests of justice”. Mr Kamal doesn’t appear to be aware of this requirement, but it doomed his application. Our report was published in February, but Mr Kamal didn’t apply to the court until August – that hardly suggests urgency.

That’s just the start of Mr Kamal’s problems. English courts have resisted interim injunctions that restrain freedom of speech ever since Bonnard v Perryman in 1891.5 Such an injunction will only be granted if it is clear that the statement is unarguably defamatory, and that no defence is possible. Again, Mr Kamal doesn’t seem to be aware of this.

There are then other oddities. The extreme vagueness of his draft order – what, exactly, was I supposed to delete? The absence of the required undertaking by the applicant of an interim injunction to pay damages if so determined by the court. The general sloppiness, with the draft order giving me a deadline that expired a month before he applied for the injunction.

For all these reasons, Mrs Justice Steyn rejected the application without a hearing, saying:

Here’s the full judgment:

I’m expecting to hear more from Mr Kamal soon.

Many thanks to my solicitors at the Good Law Project.

Footnotes

Mr Kamal was a member of Old Square Tax Chambers until November 2024. He is now based in Cyprus and practices on his own. ↩︎

Arka Wealth appears to have ceased business since our report. The related firm Benedictus Global may still be in business, although its website hasn’t been updated for a while – it still lists Mr Kamal as a member of Old Square. ↩︎

I have omitted the witness statement, because I am probably prevented from publishing it at this point, under CPR 32.12. ↩︎

As opposed to a “without notice” (or ex parte) application, which is reserved for cases of extreme urgency where alerting the respondent would defeat the purpose of the injunction (e.g., they might destroy evidence). An applicant in a “without notice” hearing is under a strict duty of “full and frank disclosure” to the court, meaning they must present all relevant facts, even those unhelpful to their case. ↩︎

Bonnard v Perryman [1891] 2 Ch 269 is a cornerstone of free speech protection in English law, long pre-dating the ECHR and the Human Rights Act, This principle has been consistently upheld, for example in Greene v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2004] EWCA Civ 1462. Before Greene, there was some debate whether section 12 of the Human Rights Act limited Bonnard v Perryman.– Greene confirmed it did not. There remains, however, an ongoing effort by claimant libel lawyers to argue that the principle is contrary to the ECHR, on the basis that the right to freedom of expression in Article 10 should be balanced with the right to reputation included in Article 8. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Chris Hamnett Cancel reply