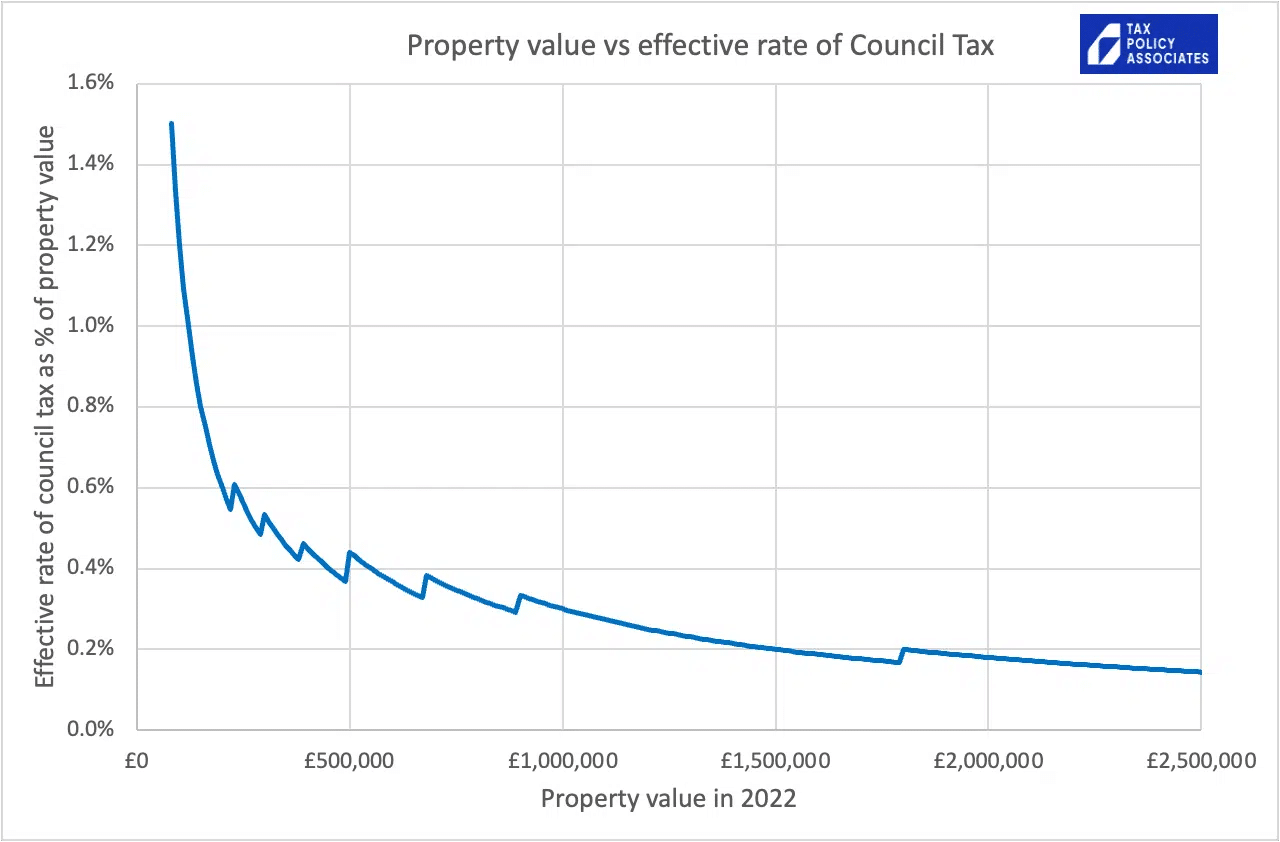

The Government needs money. Council tax is regressive – high-value properties pay a trifling sum in comparison with their value. It must be tempting for Rachel Reeves to solve both problems in one go by raising council tax on high-value properties.

We’ve created an interactive calculator that shows how this could be done, and how much could be raised.

How council tax could be raised

Council tax only slightly varies with the value of properties:

This is because of the way council tax is charged in bands, by reference to 1991 valuations. The middle band, D, is properties worth between £68,001 and £88,000 (in 1991 money). The top band, H, is properties worth more than £320,000 in 1991 (about £1.5m today). By law, band H properties are charged only twice as much council tax as band D properties. The IFS has described all this as “out of date and arbitrary” and said council tax is “ripe for reform”.

So an obvious fix is to split band H into four bands, H1, H2, H3 and H4, with H1 retaining the 2x multiplier that band H currently has, and the others having higher multipliers.

Or something more radical: a proportional property tax could be charged on properties in bands H2, H3 and H4, as a percentage of property value (but only on the value in those bands, so no “cliff-edges”).

How much could be raised?

The calculator below lets you experiment with either new multipliers or a percentage tax for high value properties. It shows how much revenue the change would raise across England, and the average council tax bills it would generate.

We split band H in four, and the slider at the top lets you position each of the new bands. Then you can choose between a “multiplier” tax and a “percentage tax” – and the revenue consequence is displayed at the bottom. You can also see the average bill someone in each band will pay (on mobile you have to click the “info” icon for that).

You’ll see that adding a few more bands doesn’t raise much money. For example, a new 3x band at £2m, 4x band at £4m, and 6x band at £8m only raises £270m. Owners of £8m+ properties pay an additional £9,000 of tax each year.

Creating a new percentage tax on top of existing council tax, on the other hand, raises more significant amounts. A flat 0.5% annual tax on all property value above £2m raises about £1bn, with owners of £8m+ properties paying an average of £90,000 more tax each year.

Or make it progressive: 0.5% from £2m to £4m, 0.7% from £4m to £8m and 1.1% for £8m+, and we raise about £1.5bn. Owners of £8m+ properties now pay £120,000 more tax each year.

These figures are just for England; if applied across the whole of the UK, expect overall revenues to be 5-10% higher. And the various approximations and assumptions in our approach mean the real-world revenues would likely be somewhat higher (see the methodology section below).

The obvious conclusion: there is potential for the Government to raise a useful amount of additional tax by taxing high value properties, but the amounts are limited.

Does extending council tax make sense?

The obvious reason to do this is that Government needs to raise tax. Raising it from people who can likely afford it, on property which is currently under-taxed, makes some sense.

There is also an equally obvious moral case for making annual tax on property more progressive. A £100m property in Mayfair currently pays less tax than a terraced house in Bolton. A fairer tax on property feels the right thing to do.

There’s a relatively small economic benefit: an annual tax creates an incentive to use/develop property that may currently be very under-used or even derelict.

There are, however, also some obvious problems:

- A percentage property tax would require somewhat regular valuations. Valuing the c4,500 properties over £10m is relatively straightforward. Valuing all the c80,000 properties over £2m is more difficult, and would require considerable resource (and take time to create). The council tax banding system was designed to avoid such difficulties.

- There will be some people in very valuable properties who don’t have enough income to comfortably afford the new tax – “asset rich, cash poor”. This is often overplayed: someone owning a £3m house usually has numerous ways to raise funds. However any new tax could include a deferral option (e.g., paying the tax as a lien on the property upon sale or death). These kinds of mechanisms are common in other countries with annual property taxes.

- The biggest problem: the tax will be capitalised into property values. The day after the tax is announced, the value of e.g. a £10m property facing (say) an annual £50k bill will fall – in principle by somewhere around £600,000.1 So someone buying the property a week later isn’t really paying the new tax – it’s paid by the person owning the property at the point of announcement (because they’re getting a lower purchase price). In the real world things tend to be not quite so tidy, but there is nevertheless an unfairness that most of the economic burden will fall on current owners – it’s like a one-off property wealth tax. There is no way to solve this problem – land tax proponents often regard it as a form of rough justice. Others may be less sanguine.

- So we can expect some people will sell to escape the tax; but that will be mostly a one-off effect, as new buyers economically are much less exposed.

- Unlike a proper land value tax, a percentage property tax somewhat disincentivises improving properties. Once you’re into the range of (say) a 0.5% property tax, then every £100k you spend improving the property triggers an additional £500 of property tax each year – in principle reducing the value of the property by about £6,000. So you’re paying £100k but receiving a net benefit of £94,000.

- Some would add another disadvantage: if (as would be wise) a percentage tax is charged on the landowner, landlords would simply pass on any additional tax to tenants. That’s widely believed, but mostly not correct: rents are primarily determined by location value and demand, not by the landlord’s costs. More tricky would be an increase in council tax multipliers; the bill would go to tenants. In the medium term rents should adjust so that most of the cost is borne by landlords, but in the short term it would be a tax on tenants in high value properties.

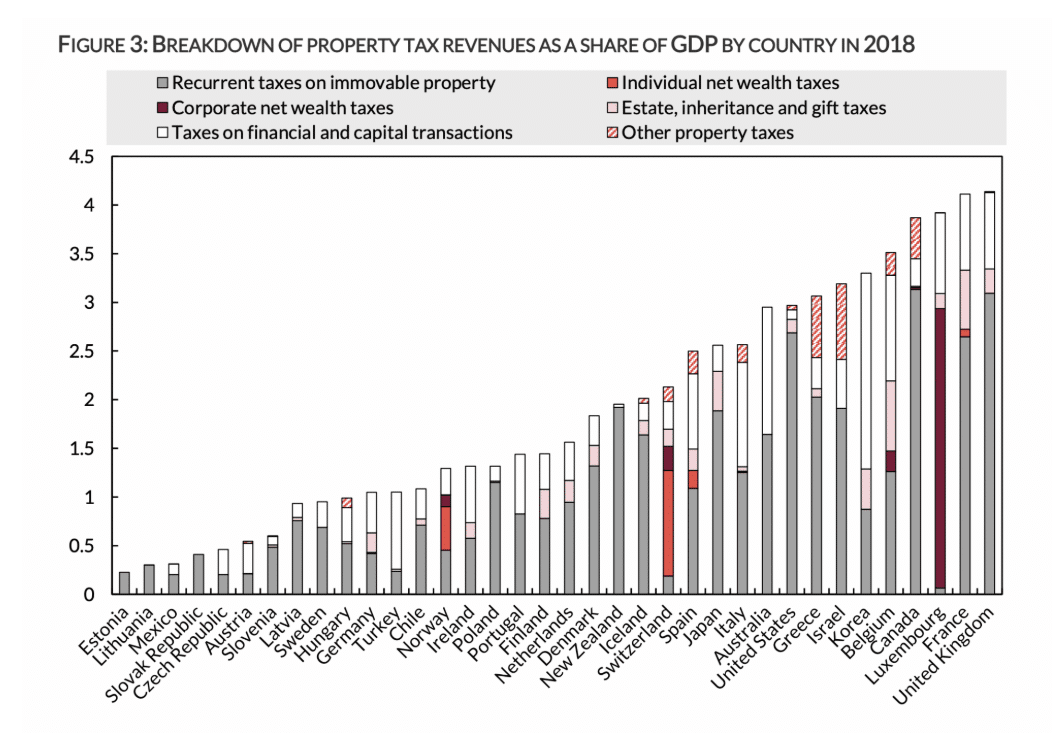

If we look at all taxation of wealth and property, the UK has higher tax as a percentage of GDP than any other OECD country:2

The reason is simple: council tax (it’s most of that grey bar – a “recurrent tax on immovable property”). And that’s council tax paid by most people, not council tax paid by the very wealthy. We under-tax high value property ownership compared to most of the world, at the same time as we overtax purchases.

My view is that there is a strong case for adding more multiplier-based council tax bands. I’m less convinced that a percentage tax makes sense given the administrative/valuation issues and the horizontal equity problem.

The balance changes once we’re looking at wholesale reform: replacing all of council tax, business rates and stamp duty with land value tax. The boost that such a reform would give to growth and homebuilding in my view more than counters the downsides. But bolting on a miniature version of such a tax as a pure revenue-raiser looks less attractive.

Methodology

The calculator works as follows:

- First, it estimates the number of properties in a given band. We weren’t able to find any reliable data on the number of high-value properties in the UK, so we estimate this using three data sources:

- The council tax data shows 154,000 properties in Band H, which (on average) means they’re worth about £1.5m today. We use £1.5m as our starting point for the new bands, and 154,000 as the “true” figure for the population of £1.5m+ properties.

- HMRC stamp duty statistics give us figures for the number of residential property transactions in six bands above £1.5m – the highest is £10m+. We use this to estimate the number of properties in England between any two values, interpolating for values below £10m and using a Pareto distribution above that. We then cap the top-end estimate, fixing the most valuable residential property in the UK at £210m (the reported value of the UK’s most expensive property).

- Some property is held in UK or foreign companies or trusts. It isn’t normally sold, and so doesn’t appear in stamp duty returns. But such properties have to pay an annual tax, ATED, and data on such “enveloped” properties is published by HMRC, in bands up to £20m. We use this data to estimate the number of properties; again interpolating when within the published bands, and using a Pareto distribution beyond that. We add the output of this estimate to the stamp duty estimate (it increases the result by 5-10%).

- When in “multiplier” mode, we apply council tax discounts (e.g. single person) and premiums (e.g. second homes) using the current data for band H. We don’t discount/premium when in the percentage mode.

This is all very approximate:

- Our assumption that annual stamp duty statistics are representative of the housing stock is clearly wrong. A flow is not always representative of a stock. Some very large estates are rarely if ever sold (think “old money”). We will therefore likely be under-counting very valuable properties, and therefore potential revenue, but we weren’t able to quantify this effect.

- There will be some double-counting (likely limited) between the ATED and stamp duty datasets, e.g. where a property paid ATED in 2023/24 and was sold that same year.

- Our analysis is for England only, but 1% of the ATED properties are in Scotland – this creates a small over-statement of our estimate. We didn’t just deduct 1% from the ATED estimates, because we expect that the Scottish properties are lower in value, and that would therefore potentially add more error than it removes.

- We apply band H data for discounts and premiums across all four of our new bands H1 to H4. It is plausible that the most valuable properties are less likely to qualify for discounts (e.g. single owners) and more likely to have premiums (e.g. second homes). Again this suggests we may be under-counting revenue.

- We assume that all properties have risen in value to 495% of their 1991 valuations. This likely over-values properties outside London and under-values property in London. It may therefore mean we significantly under-estimate values, and therefore potential revenue, at the top end. A more sophisticated analysis could account for this to some extent.

- We apply tax to the bands at the band averages; slice integration would have been more accurate – but only very marginally changed the results, and that didn’t justify the added complexity.

The code is available on our GitHub here.

Photo by Jakub Żerdzicki on Unsplash

Thanks to C for help with the modelling.

Footnotes

i.e. that’s the NPV of the stream of payments, assuming an 8% discount rate and ignoring inflation/house price rises. ↩︎

This is from the Wealth Tax Commission report – the data is a little old but it’s unlikely the overall picture has changed. ↩︎

42 responses to “Council tax on expensive homes: could the Budget raise £1bn+?”

On reflection, I think the proportional property tax is dead in the water. HMRC got £18.6bn in Stamp Duty last year, around 50% from properties >£1m in value – say £9bn. If you impose a percentage property tax on higher value properties, there will be fewer transactions, and those that remain will be at lower prices. You’re jeopardising the £9bn Stamp Duty to make perhaps another £1bn in annual tax! Seems bonkers.

The only other way would be to replace Stamp Duty completely with a proportional property tax. But it seems very brave to hope you’ll get >£18bn from a brand new tax, especially as property values would probably fall.

I believe you had some ideas here https://taxpolicy.org.uk/2024/10/18/how-to-reform-property-tax/ about reforming council tax such that it is based on value of the underlying land. Do you think that’s a step too far now? (Replacing everything with a land tax seemed convincing to me)

There is a case that you do actually want to disincentivise home improvement. Our main concern in the housing market is shortage of affordable homes, so you would want to discourage making affordable homes less affordable. You also want to encourage turning mansions into flats for example. I think this favours a property tax over LVT.

Will this wealthy tax have yo be paid out of taxed income?!?!

It sucks to be a high-value-property owner when the change is announced (this includes me), but anything which depresses the value of housing in England is a good thing – the last time I looked, we had one of the highest housing costs as a percentage of income in the OECD.

We have poor economic growth, yet we suck vast proportions of net pay from the hands of the renters and mortgage owners and funnel it to the bankers and landowners, where it typically goes into investments and not into consumption.

Bring the cost of housing down, give people more disposable income, generate some consumption-led GDP growth (hopefully without just generating inflation).

So I favour a property value tax with an estimated annual revaluation (if Zoopla can do it, so can the ONS), and aiming the tax at landowners, not renters.

Any increase in Council tax will surely be collected and spent by Councils not Central Government. Very welcome for Councils but not helping the Chancellor.

The NPV of future costs would certainly be discounted at a much lower rate than 8%, thereby underestimating the impact. Of course, this does not affect the principle that is being established

Possibly! If it’s property being rented out then that must be right. But if it’s a home, then UHNW planning would I think usually use an 8% discount rate.

Dan this is a good suggestion.

Another easy step that could be taken with council tax is to restrict the single occupancy discount to properties in bands A-D. A lot of the higher value, larger properties in the UK are not effectively utilised which is bad for the economy and the environment. Many have a single older person living in them who should be incentivised to downsize. Given the number of single person households in the UK, this change would probably raise quite a lot of additional tax (domyou have the figures?) without having any meaningful impact on property values.

There’s more to downsizing than just buying a smaller house. When you’re planning for old age you need to think about stepless access, walk-in shower cabinets large enough to hold a chair or stool, a staircase where you could easily install a stair-lift. Very many of the smaller houses fail on these criteria and hardly anyone is building bungalows now. Don’t even get me started on the financial scam that is retirement apartments.

Bungalows are always going to be relatively expensive as they require a lot of expensive land per home. This also makes it difficult to provide efficient public services (transport etc) to such areas as the density is so low.

To raise meaningful amounts, the additional payments for higher value properties would be unaffordable for many.

People bought high value properties many years ago when they enjoyed good incomes. Now retired, they can afford current council tax. But hike these substantially and there would be a glut of forced sellers unable to pay annual council taxes. This would cause a serious market dislocation like Armageddon. It would be politically suicidal.

It would mostly hit London & South East.

Somewhat unfair.

I think there is already. Lots of high end stock on the market which no-one wants to buy. Partly that’s due to high mortgage rates and more recently people have been thinking twice about buying with potential SDLT reform on the table. I actually think those hardest hit will be people that bought recently e.g. due to the pandemic – and are already struggling with high remortgage rates.

If I have understood correctly, in the short term, Dan prefers reforming Band H by introducing four’multplier’ bands within it to avoid pitfalls posited to a possible percentage against value alternative.

But that would only raise £270m annually? Peanuts in the grander fiscal scheme of things? Worth the political hassle?

Dan appears to believe in the panacea of a comprehensive land value tax encompassing council, business rates,CGT on land and property etc.

Great in theory.vision, and probable but not certain net economic snd social impact, assuming good to perfect implementation, no exemptions. and long term political acceptability and sustainability.

Such a comprehensive LVT could not be installed in one go; realistically, the best to hope and aim for, are incremental reform related to each other abd sequenced in such a way to further a direction of travel towards that destination.

Back to the beginning then. In that context, wouldn’t a percentage property tax be the best proxy for land value as part of such an incremental shift to LVT?

It’s posited pitfalls cotrespond largely with the the problems associated with a comprehensive LVT.

if it replaced stamp duty, sure. But if it’s a bolt-on then doesn’t make sense IMO.

Why not borrow elements of the French approach that actually work?

Instead of relying on outdated bands, property tax could be tied to a regularly updated notional rental value. In France this is based partly on floor area and declared condition—both straightforward measures that better capture what a property is really worth to live in. Floor area isn’t currently used, but it easily could be: EPCs, planning data, and listings already provide usable figures. Condition can be self-declared with checks and penalties to keep it honest.

Valuation itself isn’t difficult anymore. With Land Registry sales, ONS/VOA rent data, and the vast amount of information from lettings portals, fair rental values can be modelled by property type and location, and refreshed on a rolling cycle. That gives a tax base that actually tracks reality without sudden shocks.

If the aim is more revenue, greater fairness, and less buy-to-let speculation, the structure could be simple:

• a standard rate for primary homes,

• a higher rate for second homes and short-lets,

• and a surcharge for long-term vacant properties.

Linking liability to space, condition, and rental value—rather than frozen historic bands—would shift the burden onto properties with greater usable value, raise revenue more effectively, and make property speculation less attractive. The data to do this already exists.

I don’t think applying a tax as a percentage of property value would work. Once you decide you’re applying a “progressive” rate of 1.1% to properties above £8m (say) then what’s to stop future governments increasing the rate as government debt continues to rise? I can’t see ultra-wealthy folk being willing to take this risk.

One great advantage of SDLT currently is that even though it can hit 12%, once you’ve paid it that’s the end of the matter.

Splitting band H as illustrated makes more sense.

What is the risk for them? They can downsize or arbitrage with other assets which may be more tax efficient.

The risk is that the property falls in value significantly when tax rates are hiked. To quote the article: “The day after the tax is announced, the value of e.g. a £10m property facing (say) an annual £50k bill will fall – in principle by somewhere around £600,000”. So if the government decides to hike the rate by 0.5% in future, they lose 6% of the property value. I suspect they simply wouldn’t buy here – there are other countries where this is less likely to happen.

Yes, arbitrage. They are not scrimping and saving for a big house which is their main asset. It’s just *an* asset. I think your underlying assumption is that if they own a residential property here (which is distinct from whether they are resident here) will invest more in the UK and that investment is beneficial for the UK economy. The evidence to support that is at best neutral. Dan’s point is that Council Tax is it’s present form is highly regressive.

My Mother could never understand why film stars rented their homes in LA. They should buy she said, renting is a waste.

Surely exactly the risk they are taking with SDLT rates? If the government doubles them tomorrow, the value of property will adjust downward to reflect this.

What’s being suggested is that if people can’t afford LVT then they can downsize. I’m saying that they can’t do this without incurring a capital loss, to compensate for the fact that LVT would apply. This is completely different from doubling SDLT after someone has bought a property. If that happens then the owner can keep living there because the taxes they pay each year haven’t risen, I.e. they don’t need to downsize.

I wonder whether property valuations would be a real issue.

With the odd exceptions I think it is fairly well known what a property are likely to be worth and, via planning applications, it known when capital improvements have been carried out.

Having learnt from experience if you extend/improve a property then, at present, there’s no immediate change to the council tax band – it is only when a sale/purchase occurs that councils look to move the property into a higher band.

What about councils considering whether a band change is appropriate as part of agreeing planning applications with the result that council tax receipts increase immediately rather than possibly years later.

Council tax values can be appealed and a charge for lodging an appeal that fails could discourage frivolous ones.

Will the extra money raised go to the Treasury or local government? If the latter, will those councils with lots of high value properties be able to reduce Council Tax for all their residents and thus reduce the total tax collected in their area back to what it was previously?

Might we end up with even greater tax inequality between central London and the North?

This is great work Dan. It’s a shame the government/Civil Service don’t have the talent?/time?/inclination? to do quality analysis like this and we have to rely on outsiders to do do their jobs for them! I am sure there are talented individual Civil Servants capable of this but somehow collectively output is terrible.

To be fair, Non, I suspect these sort of background analyses are undertaken within HM Treasury; the real issue is their underlying purpose related to the wider political backdrop/drivers.

Of course, the question asked and the informational purpose/content is itself political.

I suspect that quite of last week’s activity last using selected journalists/policy analysts was, at least in part, the summer start to the budget political gaming process, which will now continue into the autumn.

Indeed, Dan’s invaluable analysis raises value/redistributional/sequencinquestions as much as technical impact/efficiency oBE that

Believe that Australian finance department publishes a Dan-like tax reckoner but more comprehensive allowing stakeholders and the public to model themselves changed to the system

That is more transparent.

Apologies, Jon.

It seems like an intelligent alternative to a wealth tax, but does it not suffer the same problems? Those who are asset rich but cash poor would have to sell up? Perhaps that is not such a disaster, but would drive significant whining in the Telegraph.

Equally, might the govt not charge a higher rate of council tax to non-UK resident owners and buyers? And to residents with multiple homes? Such systems exist in Italy, and could disincentivise holding empty homes as speculative investments.

it is like a wealth tax, but only on houses, and mostly only for the day one owners (per the article). A small wave of people selling high value houses doesn’t have a bad macroeconomic effect; possibly the opposite.

How about making SDLT a lifetime charge so that when selling and buying another home, you only pay SDLT on the upgrade? This reduces or eliminates the disincentive to move to appropriate housing as and when sensible (like when you have children, or get switched hospitals as a doctor, or schools as a teacher, or want to be near relatives when you retire). It would also remove the disincentive for downsizing.

Eg buy House A for £300k. Pay commensurate SDLT

5y later sell House A for £500k and buy House B for £900k. You pay SDLT of whatever the rate is for £900k less whatever the rate is for £300k (or perhaps just less a credit for SDLT paid originally).

When you downsize, unless inflation has been rampant, you would pay no SDLT.

If moving between houses of roughly the same value for reasons of work/school/wider family then there would be no transactional charge at all.

So someone ending up in a £2m house, say, would have paid the same total lifetime SDLT whether they arrived there in 10 intermediate steps or just 2.

Second homes could be dealt with outside this regime – or in their own current eye watering SDLT category, but still with credits.

like most proposals for reforming SDLT it would be an improvement but massively reduce the revenue. And the only reason SDLT is around is for the revenue…

Couldn’t the rate be set at a level designed to make it revenue neutral?

How about abolishing SDLT and replacing it with CGT of 3-5% of the inflation-adjusted gain?

A CGT charge when owner sells would discourage sales and increase prices to recoup the tax liability.

The gain would need to be indexed otherwise you simply being taxed for inflation.

Such changes could be rolled in over 15 years to avoid drama. Why not 1% extra council tax per year, for fifteen years, on all values over the national average house price? (A reference point handy for inheritance tax, too…)

As council tax is paid by residents not property owners – what would be the effect on renters ( who are already paying very high rents, particularly in the southeast ) ? This segment of the property market does not seem to be included in any of the property tax debate / calculations

good point – in the medium term rents should adjust so that most of the cost is borne by landlords, but in the short term it would be a tax on tenants in high value properties.

Under the current “Renters Bill” which should be receiving Charlie’s splodge very soon, rent rises are limited to CPI+H and it will retrospectively apply to all AST’s and Standard Contracts (Wales). So it is possible that new contracts will be substantially more expensive because of this and the possible reduction of the supply side of the PRS. It makes housing more expensive in liquidating the asset but then that is the point. Would need a lot of sliders to model.

Has the government accepted the Lords Young and Best amendment to limit annual rent increases for three year periods, then?

You are right, they didn’t:

https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3764/stages/19515/amendments/10019082

so S.13 still applies. Rent rises will not be automatic so the effect will be slower/faster depends on the tribunal. Who knows? What is there may or may not be a limit but the clear intention was not to accellerate rent inflation.

An advantage to the current council tax design is that (by design) it doesn’t incorporate numerical thresholds that allow for fiscal creep. Increases in council tax are explicit (% increases YoY) and transparent. Multipliers on existing banding would be the right way to go. The issue I have with taxes based on fixed ££ amounts on property is that it creates another opportunity for the pretence of ‘no tax rises’ while more people fall into higher paying bands through inflation.

Slider controls. Yay! Great Stuff. It would be interesting to see if a Reecheal Raves tries it out. For a friend, of course.

I suspect some of the major news outlets will turn it up to 11, double the output and put it in a big font on their homepages.