Last month, parents backed by the Independent Schools Council made a legal challenge against the Government’s decision to charge VAT on private school fees. We’re publishing the grounds of the challenge and our analysis.

The challenge is more political than legal – it cites no relevant legal precedents and has very poor prospects of success. But if it did succeed then the consequences would be far-reaching. It’s asking for ultra-orthodox Jews, very religious Muslims and foreign nationals to be exempt from VAT on private school fees. We’d have a tax system that discriminated on the basis of nationality and religion. We’d also have opened the door to challenges against many other features of the tax system.

I should say at the outset: I have no view on the question of whether the political decision to charge VAT on private school fees is correct. I can see arguments on both sides, and I have no expertise in education policy. My interest is in the legal question of whether the challenge has any realistic prospect of success, and the broader question of whether and when tax policy should be subject to judicial review.

Updated below with the full skeleton arguments.

The grounds

Here is the full “statement of facts and grounds” – the key document prepared by the Claimants. Right now we don’t have anything else – in particular we don’t have the Government’s defence, or the more detailed (“skeleton”) arguments. However this document will contain the fundamental legal and factual basis for the Claimants’ case:

The grounds are redacted in line with an earlier anonymity order to protect the identity of the children involved (the claimants) and their parents (the “litigation friends”).

The background – challenging tax legislation

My starting point is that I am uncomfortable with the idea of judicial review of tax legislation. Tax is political, and it is to be expected that most or even all taxes will be opposed by some people, many of whom will have a strong ideological and/or economic incentive to bring a challenge against the tax. If this were permitted (in any but the most extreme circumstances) then we would see a wave of such cases, as the cost of bringing a case would often be much less than the potential benefit of having a tax reversed. Our tax system would become even more incoherent than it is already.

This is absolutely something we saw during the UK’s membership of the EU. Taxes could be challenged, annulled and damages claimed, on the basis that the tax was contrary to EU law principles. We saw a wide range of such challenges, by taxpayers and the European Commission, either under general EU law principles (such as the free movement of capital or the freedom of establishment) or specific EU legislation (such as the capital duties directive). These claims cost the UK billions of pounds, and greatly complicated UK tax policy.

This was not anticipated when the EU was created; direct tax was reserved to Member States, with unanimity required before the EU could legislate on direct tax matters. The EU institutions have always disliked this unanimity requirement and, perhaps as a consequence, the CJEU showed little or no deference to Member States. The result was a mess of muddled and inconsistent⚠️ jurisprudence.1 One of the benefits of Brexit is that a significant and unpredictable constraint on tax policy has been removed.

Human rights tax challenges have the potential to be even more disruptive to the tax system. Taxes by their nature impact the right to property, protected under Article 1 of Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Taxes also tend to treat similar things in different ways, and that is potentially discrimination, which is prohibited under Article 14 unless it can be objectively and reasonably justified. It’s easy to argue that there’s no objective/reasonable justification for (to take some examples) taxing employment income more than self-employment income, taxing labour income more than investment income, taxing commercial real estate transactions more than residential transactions, taxing bankers more than private equity executives, and taxing retired people less than working people. Each of these likely indirectly discriminates against certain groups, particularly people of different ages and ethnic backgrounds2

So we would have chaos if the ECHR was receptive to challenges to tax legislation. Fortunately it has not been. When it comes to tax legislation, the ECHR gives a wide “margin of appreciation” to national governments:

“in the field of taxation the Contracting States enjoy a wide margin of appreciation in assessing whether and to what extent differences in otherwise similar situations justify a different treatment“.3

and:

“The Commission is of the opinion however that it is for the national authorities to make the initial assessment, in the field of taxation, of the aims to be pursued and the means by which they are pursued: accordingly, a margin of appreciation is left to them. The Commission is also of the view that the margin of appreciation must be wider in this area than it is in many others. The Commission recalls in this respect that systems of taxation inevitably differentiate between different groups of tax payers and that the implementation of any taxation system creates marginal situations.“4

and:

“The Court has often stated that the national authorities are in principle better placed than an international court to evaluate local needs and conditions. In matters of general social and economic policy, on which opinions within a democratic society may reasonably differ widely, the domestic policy-maker should be afforded a particularly broad margin of appreciation.“5

This “margin of appreciation” doctrine is not unique to tax, but is applied with what has been described as “extraordinary” stringency to tax matters. We can see how serious a rule this is when we count the number of substantive tax rules6 that have been ruled contrary to the ECHR. I believe there are only two:

- The Netherlands exempted unmarried childless women over 45 from certain social security taxes; men were not exempt. That was successfully challenged. The Dutch Government had already changed the law and its defence was decidedly half-hearted.

- Hungary imposed a 98% tax on the retirement income of a civil servant only two months before they retired. The Hungarian constitutional court annulled the tax for being retroactive; the Hungarian Parliament amended the constitution, and the constitutional court annulled it again. In such extraordinary circumstances, the ECHR found the tax contrary to the ECHR, and awarded a small amount of compensation. Other attempts to challenge more modest increases in pension taxation have failed.

Every other case we’re aware of has failed. Various ECHR challenges against retrospective taxation in the UK and elsewhere have all failed.7 Two elderly sisters failed in a challenge against the inheritance tax exemption which would apply to a married couple but not to them.8 The fact The Netherlands taxed financial assets more favourably than business assets was not discrimination. The German tax system applies a church tax to irreligious spouses of churchgoers – but that wasn’t a violation. There are many others – there is an excellent introduction the caselaw by Philip Baker KC here (a little old but still very relevant) and a fascinating statistical analysis of ECHR tax caselaw here.

The UK courts have been similarly sceptical to attempts to challenge primary legislation.9 Here’s Lord Bingham on the attempt to challenge the ban on hunting:

“The democratic process is liable to be subverted if, on a question of moral and political judgment, opponents of the Act achieve through the courts what they could not achieve in Parliament.“

All of this means that tax/ECHR specialists have been deeply sceptical of the idea that VAT on private schools could be challenged; I am unaware of any expert suggesting the JR has any realistic prospect of success.1011

My assessment of the case

There are several odd aspects to the Claimant’s grounds. The document doesn’t cite any of the ECHR caselaw where tax legislation is challenged.12 It doesn’t contain the phrase “margin of appreciation”, much less grapple with that doctrine. There is no acknowledgment of how serious step it would be for primary tax legislation to be held contrary to the ECHR, or what the wider consequences would be.

The arguments they do make are more political than legal, and either based on no authority, or based on authority that is being cited out of context.

- Central to the argument is the claim that VAT hinders access to education. There is, however, no ECHR authority that “hindering” access to private education violates the right to education in A2P1. The only authority cited is (para 50) an obiter remark in a CJEU EU VAT case⚠️ that looked at the purpose of the VAT exemption (in the very different context of the Commission successfully challenging a German *expansion* of the exemption to higher education research). The purpose and interpretation of the education exemption is of little or no relevance to the question of whether it’s permissible to restrict the exemption by statute.

- Paragraph 51 is where the leap is made that “hindering” education violates the right to education. No ECHR authority or other justification is given for this leap.

- “Hindering” is said to be so strong a principle that any “more than de minimis” impact on “at least some parents” is a violation (see paragraph 53). The authority given for this proposition is a Şahin v Turkey, where a student was suspended from a Turkish university for wearing an Islamic headscarf. This was, however, a case where the court found there was no ECHR violation. Far from establishing that a “more than de minimis restriction” is a violation, the court said that “Consequently, the Contracting States enjoy a certain margin of appreciation in this sphere, although the final decision as to the observance of the Convention’s requirements rests with the Court. In order to ensure that the restrictions that are imposed do not curtail the right in question to such an extent as to impair its very essence and deprive it of its effectiveness, the Court must satisfy itself that they are foreseeable for those concerned and pursue a legitimate aim“. This is a very different standard to “more than de minimis“. I do not know why the Claimants think Şahin helps their case.

- An obvious problem with the “hindering” proposition is that there are a great many rules and regulations which could be said to “hinder” private schools. There is also tax – private schools have historically borne VAT on the goods and services they buy, and paid PAYE/national insurance for their staff. Para 51 just hand waves this: “But VAT is different: it is a tax on the very provision of the educational services to which access is guaranteed by A2P1”. That’s rhetoric, not argument. What is the principled distinction? The Claimants don’t tell us. There seems a heavy status quo bias – everything that existed before January 2025 didn’t “hinder” education, but imposing VAT on private education does. Why?

- None of the cited cases relate to tax. None are even close to the facts of this case. For example, Memlika v Greece and Tarantino v Italy are cited as authorities for the proposition that access to educational facilities can only be consistent with A2P1 if it is proportionate to a legitimate aim. But Tarantino was a case where the “margin of appreciation” of the state was narrower because the state was trying to regulate autonomous private schools. Memlika was a case involving a complete denial of education, not a “hindering”.

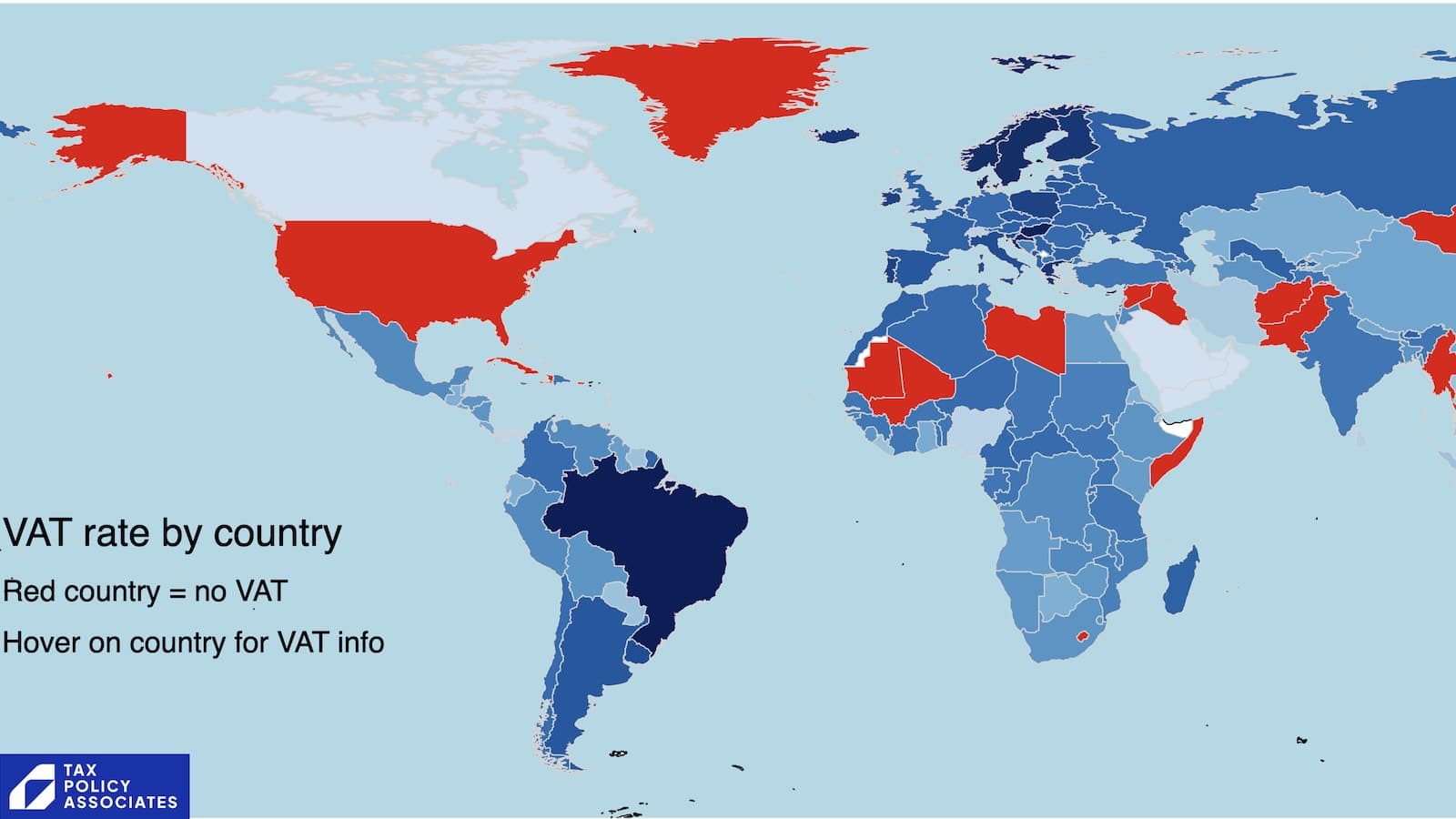

- The grounds think it’s helpful to their case that no other EU state imposes VAT on private schools. But tax systems are very different across Europe, and every one has its unique features. The fact tax systems mostly work in a particular way is not evidence of a consensus that any other way is contrary to the ECHR. The uniqueness of the German church tax was not an argument for it being contrary to the ECHR.

- The discrimination argument is incoherent. A SEN child without an EHCP is massively disadvantaged compared to a child with an EHCP because they have to pay school fees. Is that an ECHR violation? If it is, that obviously has very wide implications. But if it’s not, then why is imposing VAT on top of the fees a violation? The grounds say that “It is accepted that the State is not obliged to subsidise or otherwise establish independent schooling“. But why? The grounds say it’s because VAT isn’t a subsidy – but economically there is no difference between a cash subsidy and a targeted exemption. It’s another distinction without basis in logic or ECHR caselaw.13

- The real issue with SEN is that it is often very hard to obtain an EHCP. Many SEN parents would love to be able to send their children to state schools with better SEN provision. Others would love to send theirs to their private schools, but the main barriers are the cost (with or without VAT) and the fact that many private schools will not accept SEN kids. All of this would seem an excellent basis for a challenge to the SEN/EHCP system (either generally or in individual cases). The complaint here is misdirected.

- There are then a series of arguments that the VAT change is disproportionate because it causes some individuals financial hardship – it is “imposed without any regard to the income or wealth of the affected families and their ability to pay”, and wealthy parents whose children attend state schools won’t have to pay (paragraph 64). The proposition that this creates an ECHR violation is very ambitious – many taxes have this effect (including, some would say, the whole of VAT). It’s the kind of “marginal situation” which the ECHR accepted in Lindsay v United Kingdom was often inevitable. But the Claimants just breezily invent a new principle that taxes must be progressive in all cases, without any sign they’ve thought about the implications.

- The grounds go further. It’s claimed that that Guberina v Croatia means that tax legislation is required to include exceptions from general rules to prevent indirect discrimination against particular groups (see paragraph 68). So the UK is apparently required to facilitate foreign nationals’ desire for their children to be educated “in conformity with their home country’s requirements” (paragraph 78). Again, VAT seems the least of the problems here.

- The remedy sought is rather bold: “a declaration of incompatibility in respect of those individuals in the identified categories“. So children with special education needs (with no EHCP), ultra-orthodox Jewish and very religious Muslim families, and foreign nationals, would receive a VAT exemption, but nobody else would? That’s unworkable practically. More seriously, it would be discriminatory. Imposing VAT on private schools isn’t contrary to the ECHR – but the remedy sought by the Claimants would be.14

The real test that should be applied, based on the caselaw, is whether the imposition of VAT on private schools “impairs the very essence of the right to education or deprives the right of its effectiveness” – the test in the Turkish Sahin case which the Claimants cite out of context.

Once we’ve established that’s the test, then it’s clear there is no claim. It seems plausible that banning private education, or taxing it at 100%, would be a breach. But a 20% VAT (which in practice imposes a cost of around 15%) does not “impair the very essence”.

The best argument the claimants have is against the imposition of the tax in January, in the middle of the school year. I felt this was unfair as a practical matter. But given that ECHR permits retrospective taxation, it seems unlikely that hurried implementation is a violation.

I expect the judgment will follow the 2021 Supreme Court decision on the attempt to challenge the two-child benefit cap:

- The assessment of proportionality, therefore, ultimately resolves itself into the question as to whether Parliament made the right judgment. That was at the time, and remains, a question of intense political controversy. It cannot be answered by any process of legal reasoning. There are no legal standards by which a court can decide where the balance should be struck between the interests of children and their parents in receiving support from the state, on the one hand, and the interests of the community as a whole in placing responsibility for the care of children upon their parents, on the other. The answer to such a question can only be determined, in a Parliamentary democracy, through a political process which can take account of the values and views of all sections of society. Democratically elected institutions are in a far better position than the courts to reflect a collective sense of what is fair and affordable, or of where the balance of fairness lies.

- That is what happened in this case. The democratic credentials of the measure could not be stronger. It was introduced in Parliament following a General Election, in order to implement a manifesto commitment (para 13 above). It was approved by Parliament, subject to amendments, after a vigorous debate at which the issues raised in these proceedings were fully canvassed, and in which the body supporting the appellants was an active participant (para 185 above). There is no basis, consistent with the separation of powers under our constitution, on which the courts could properly overturn Parliament’s judgment that the measure was an appropriate means of achieving its aims.

There are several parallels with the attempt to challenge VAT on private school fees: a controversial measure which had been a manifesto commitment, impacting (in some cases) vulnerable children, and where the body supporting the claimants (here the Independent Schools Council) had been an active participant in the political debate.15

The skeleton arguments

The main skeleton argument for the claim is here:

There’s a separate skeleton from the lawyers representing four Christian schools:

And another – the strongest – from the lawyers representing SEN parents:

The Government’s defence skeleton is here:

I didn’t have the skeletons when I wrote the article, and haven’t amended it. Reading through the skeletons, I’m struck by the Claimants’ failure to engage with any of the ECHR tax caselaw. “Margin of appreciation” gets a mention (paragraph 70 of the main Claimant skeleton), but with the incorrect claim that in this case it is “especially narrow”. The SEN Claimants’ skeleton makes a similar mistake (see paragraph 44).

The Government’s response correctly notes that test for A2P1 is whether “the very essence of the right” is impaired (paragraph 24.2) and that the margin of appreciation is in fact very wide (paragraphs 75.2 and 68.2). I expect the latter will be the issue that disposes of the claim (although the discrimination discussion will be interesting).

Finally, there was a side-issue involving the admissibility of Parliamentary select committee reports. Two submissions by the Speaker can be found here and here.

Many thanks to M for reviewing an early draft, and to K and T for their human rights expertise.

Footnotes

The tax State aid caselaw is even worse. ↩︎

For example, some ethnic groups are more likely to be employed, and less likely to own a business. ↩︎

By contrast tax administration and procedure is subject to a much lower threshold and has often been ruled contrary to the ECHR. ↩︎

The “bedroom tax” case went against the UK, but the measure in question was not in reality a tax and the ECHR did not treat it as one. ↩︎

I am sympathetic to the dissenting judgments, which suggest this was discrimination but within the margin of appreciation. Philip Baker KC wrote a convincing critique of the majority judgment’s discrimination analysis. ↩︎

There is a good summary of the historic relationship between Strasbourg and the UK courts in this 2011 speech by Lady Hale. ↩︎

Excluding, of course, those acting for the parties. ↩︎

A further barrier is that, even in principle, the Human Rights Act cannot override primary legislation – all a successful challenge can do is provide a “declaration of incompatibility“, asking Parliament to think again (although it seems most unlikely that Keir Starmer would ignore a judgment which said the VAT change was an ECHR violation. ↩︎

The closest is Guberina v Croatia, which concerned indirect discrimination in the application of tax legislation by a local tax office. ↩︎

The grounds also suggest that access to existing institutions is protected under A1P1. Quite how being at a school is a “possession” within the ECHR caselaw is unclear, and once more no authority is given. ↩︎

I expect the Independent Schools Association doesn’t remotely want this outcome, and they expect that the education VAT exemption would be restored if their case is successful. But that’s not how the law works – they are bringing a case on narrow grounds and the courts should take those narrow grounds seriously. ↩︎

Thanks to Michael O’Connor in the comments for pointing out those parallels. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Andrew Cancel reply