OneE made £10 million selling doomed R&D tax schemes – leaving investors with nothing and taxpayers footing the bill. Here’s how they did it, and here’s how we would change the law to end the tax avoidance industry for good.

The scheme involved an attempt to use research and development tax relief to generate tax losses for investors far in excess of their actual investment. It was pure tax avoidance, and so technically hopeless that the promoters didn’t even try to defend its main feature in court. The judgment is LR R&D LLP v HMRC.

The continued existence of these tax avoidance schemes is an example of market failure. Investors get ripped off and (more importantly) the lost tax means that the rest of us end up paying more tax (or having worse services).

The scheme

OneE is a well known tax avoidance promoter. They’ve been doing this for years and made tens of millions of pounds of profit.

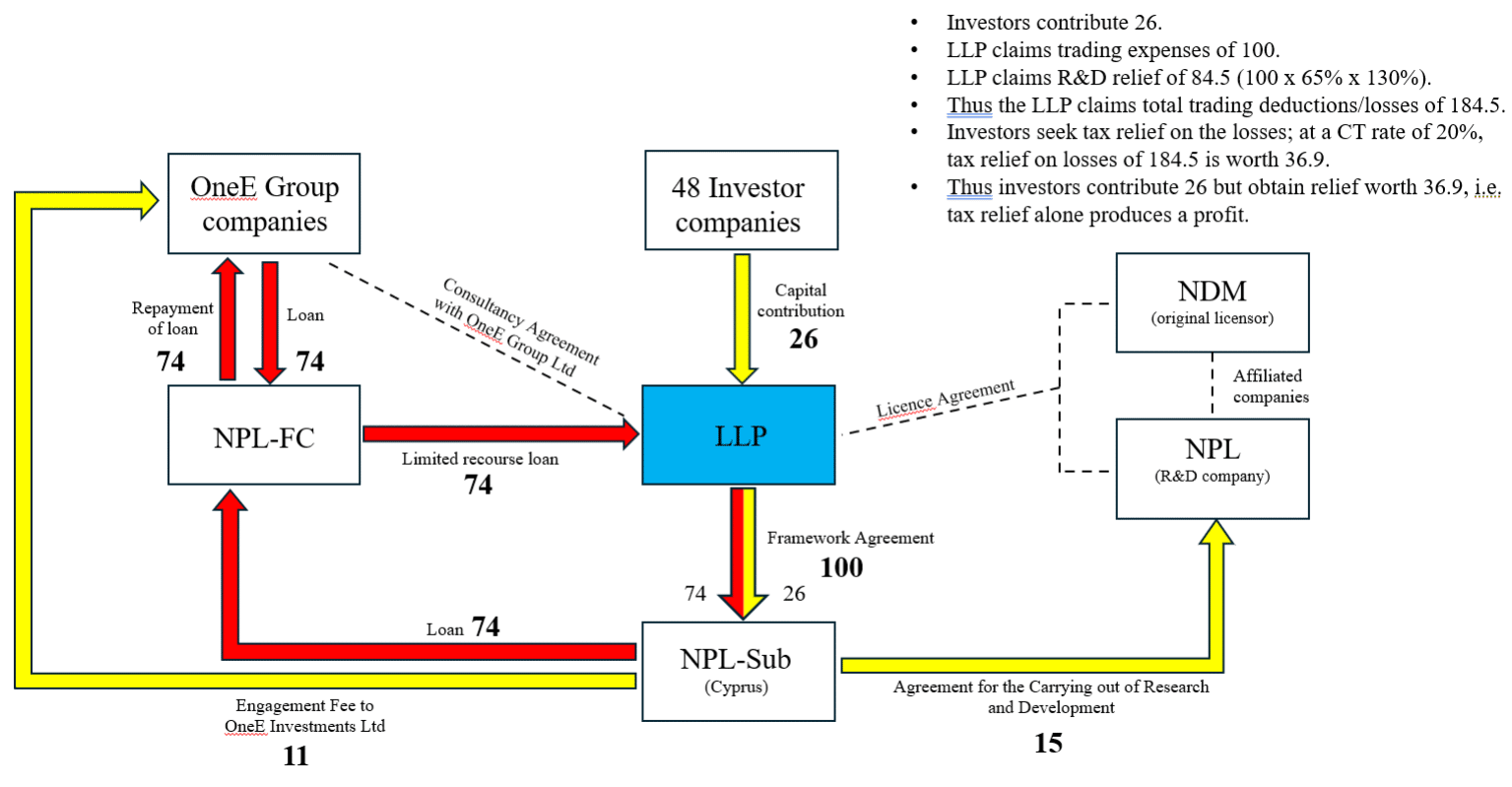

OneE wanted a scheme that let it sell tax relief to clients. The pitch was: invest £26k and, even if you lost everything, you could claim tax losses of £184k. Those losses would be worth £36.9k at the then-corporation tax rate of 20%.

How do you achieve such magic?

- Establish a UK limited liability partnership – an LLP. An LLP behaves a bit like a company, and a bit like a partnership. But the key thing is that it is usually tax “transparent”. If you own an LLP, and the LLP does something, you’re taxed just as if you did that thing.1

- The client puts in £26k.2

- The LLP then borrows £74k from a company called “NPL FC Limited“. It’s a very strange loan, because it’s “limited recourse” – the LLP only has to repay the loan if it makes a return from its investments. No real loan would work like that.

- Where did NPL FC get that £74k? It borrowed it from OneE, the tax avoidance shop.

- The LLP now had £100k from the clients and the loan. It uses all of this to enter into a “framework agreement” with a company called NPL Subcontractor Limited to undertake R&D expenditure. NPL Subcontractor is a Cyprus incorporated company owned by OneE.

- Behind the scenes, NPL Subcontractor makes a £74k loan to NPL-FC, which repays OneE. So the weird £74k loan never really existed. The money just went in a big circle.

- What about the remaining £26k? £11k is paid in fees to OneE, and £15k is used for actual R&D expenditure.

It’s all set out in this diagram included in the judgment.

Let’s say for the moment that the entire investment failed (spoiler: that’s what happened). The LLP claims it has £100k of losses, and these are available for the client, as it’s a member of the LLP and the LLP is “tax transparent”.3

Usually £100k of losses would be worth £20k (as the relevant rate of corporation tax at the time was 20%). But R&D expenditure had a special tax regime, which magnified the losses to £184.5k – worth £36.9k.

So this is how the magic happens: you can invest £26k and get back £36.9k, thanks to the taxman.

And this reflects many previous failed schemes, which all shared the same basic pattern: claim tax relief through an LLP, and “juice it up” through debt. The debt, as with LR R&D LLP, doesn’t really exist, but supposedly means that investors can claim tax relief in excess of their actual investment. These schemes have all failed.

How it failed

The structure was a disaster for the investors. HMRC opened an enquiry and denied tax relief. OneE appealed this decision to a tax tribunal.

It was obvious that the £74k went around in a circle, and so wasn’t R&D expenditure at all. OneE didn’t even bother defending the point in their appeal. That alone meant the structure failed – without the debt “juicing up” the investment, the numbers don’t add up. The investors would now be investing £26k and (assuming the small actual R&D expenditure didn’t produce a return) generating only £48k of tax losses, worth under £10k.

It’s worth pausing to stress this point. The key element of the structure – the feature that made it attractive to investors – was indefensible in court.

That, however, would be the best case scenario. The LLP wasn’t in the best case scenario. The tax tribunal ruled that no tax relief was available at all, for two reasons:

First, tax relief was only available at all (even on the amount actually used as R&D) if the LLP was “trading” – a technical tax term which broadly means you’re just not sitting on a passive investment but actively pursuing profit. The LLP was just passively sitting on its investment, and wasn’t trading. The LLP gets no tax relief.

Second, even if it had been trading, the payments by the LLP were not made “wholly and exclusively” for the purposes of the trade, because they were so heavily motivated by tax considerations. So there would still be no tax relief.

Altogether, the investors in the LLP put in £2m. They lost it all.

There were ten other LLPs – we can track some of them through OneE’s ownership. The investors appear to have been small and medium sized companies. One of them, Pipework Northern (UK) Ltd, liked the scheme so much that it invested in seven LLPs.

A related court judgment suggests OneE’s clients put in £77m in total. All of that was lost.

How it succeeded

The structure was a great success for OneE. It made £906k in fees from this LLP. The figures in the related court judgment suggest OneE’s total fees were at least £10m.4

That wasn’t all kept by OneE. Clients are usually sold this kind of scheme by “introducers” – accountants and independent financial advisers who should know better. One of the reasons they don’t know better is the large introduction fees they receive – here that totalled £2.5m.

So OneE made millions selling an aggressive tax avoidance scheme that never had a chance of succeeding, and it didn’t even try to properly defend in court.

Two of the directors of OneE are Dominic Slattery and Bashir Timol.

The stolen scheme

The R&D scheme here wasn’t invented by OneE, Slattery or Timol. It was designed by an Irish adviser called Kieran Corrigan. He pitched the scheme to Dominic Slattery and another individual called Timothy Johnson, after they’d signed a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). Mr Timol wasn’t present at that meeting.

OneE later sold the scheme in breach of the NDA.

Corrigan’s company sued OneE and Messrs Slattery, Johnson and Timol personally for breach of confidence. OneE, Slattery and Johnson were found liable for breach of confidence and an “unlawful means conspiracy”.

Mr Timol was not, because he said he wasn’t aware of the NDA. Newly discovered documents called that into question and so Mr Corrigan won on appeal; Mr Timol’s liability will now be the subject of a separate trial.

The judgments in this side-dispute are illuminating, not least because they reveal this as yet another technically hopeless tax avoidance scheme facilitated by tax KC Robert Venables.

The history of dubious R&D claims

OneE has an associated firm that provides R&D tax credit advice – Diagnostax. It appears to be owned by Messrs Timol and Slattery’s wives (via another company called Protech Professional Ltd).

Diagnostax used to operate under the business name of “Radish”. In 2022, The Times caught Radish advising that a pub could claim £28k in tax relief for developing vegan and gluten-free menus.

At the time, Radish’s website included this quote from the pub’s owner:

“I actually didn’t think we’d have a claim, I still can’t believe it – we’re only a small restaurant & hotel! But having spoken to Tim, it’s down to all the hard work that goes into crafting our menus to cater for vegetarians, vegans and those with a gluten-free diet. It’s very difficult to get a menu that suits all tastes and needs, and we can’t have half a dozen different menus as it doesn’t make economic sense. Looking at a menu you don’t see the work that has gone into it, but we do it because we want to please everyone who walks through the door – that is R&D for The Coach House Inn.“

Needless to say, this is pure nonsense, and the defence which Diagnostax provided was risible.

Diagnostax is still making far-fetched claims: their website asserts that 50% of clients can claim R&D tax relief.

They’ve branched out: Diagnostax’s main offering is a “sustainable and profitable tax advice and consultancy service that integrates into your business”. In other words, they’re providing tax advisory services to small accounting firms that lack tax expertise. Given the history of Diagnostax and the people behind it, and their legacy of (at best) inexpert tax planning, we would be highly suspicious of this offering.

A peculiar pharma company

The R&D expenditure was carried out by Nemaura Pharma, which is described in the tribunal judgment as a private pharmaceutical company.

There are several oddities around Nemaura Pharma and its associated entities.

The delisted Nasdaq company

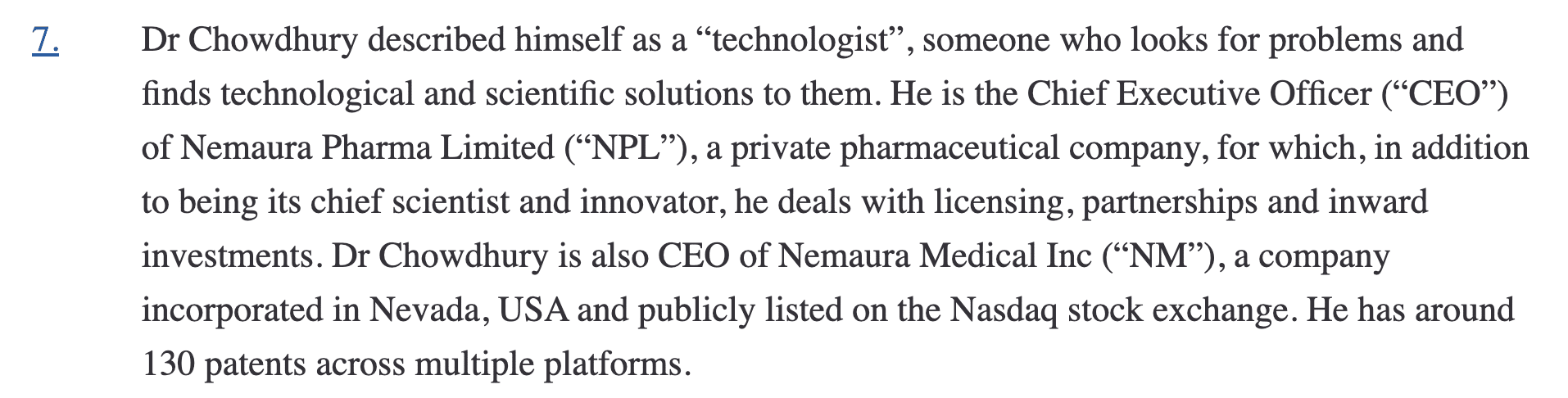

Here’s how the business was described in the tribunal judgment:

Nemaura Medical Inc was delisted from Nasdaq in January 2024 because its shares fell below $1 and it then failed to file an annual report and “terminated” its staff. The tribunal hearing was in November 2024; it’s unfortunate if the tribunal was given the false impression that Nemaura Medical Inc had any substance.

The tax-heavy pharma company

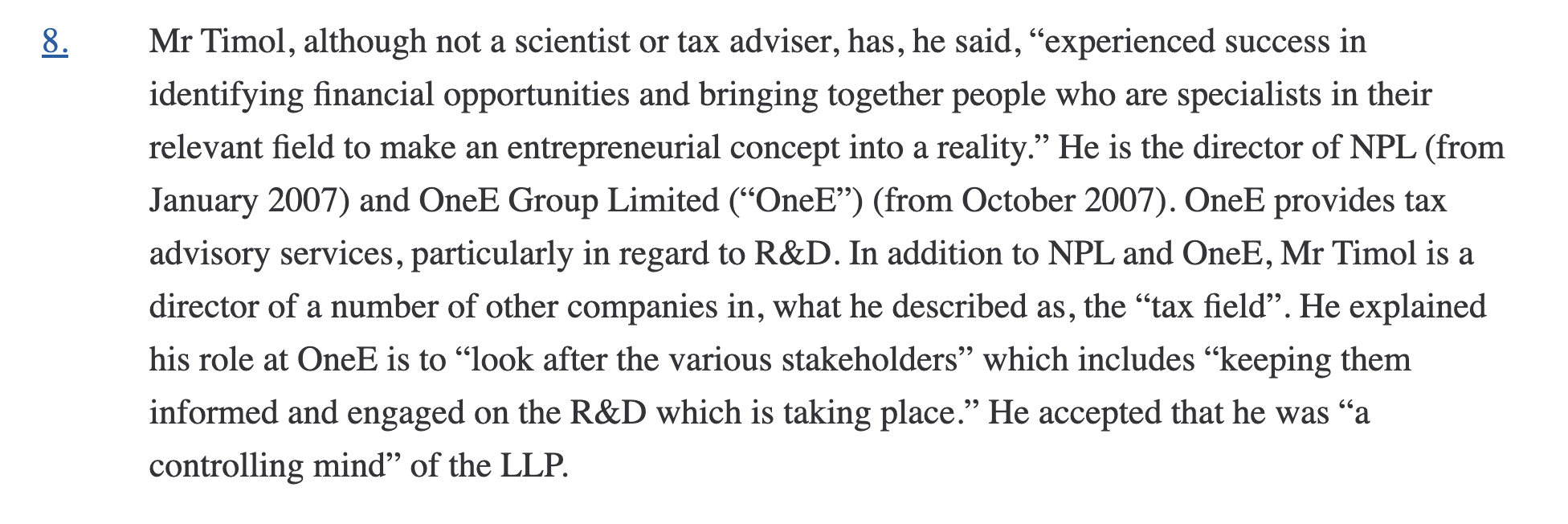

Another oddity: Nemaura Pharma Limited was jointly controlled by Dr Chowdhury and a Mr Bashir Timol, a director of OneE (whose main business is selling tax avoidance structures):

When Nemaura Medical Inc listed on Nasdaq, its six-man executive team consisted of Messrs Chowdhury and Timol, one opthalmic surgeon, one accountant and two chartered tax advisers.

Why would a startup pharma company care so much about tax?5

The unusual accounts

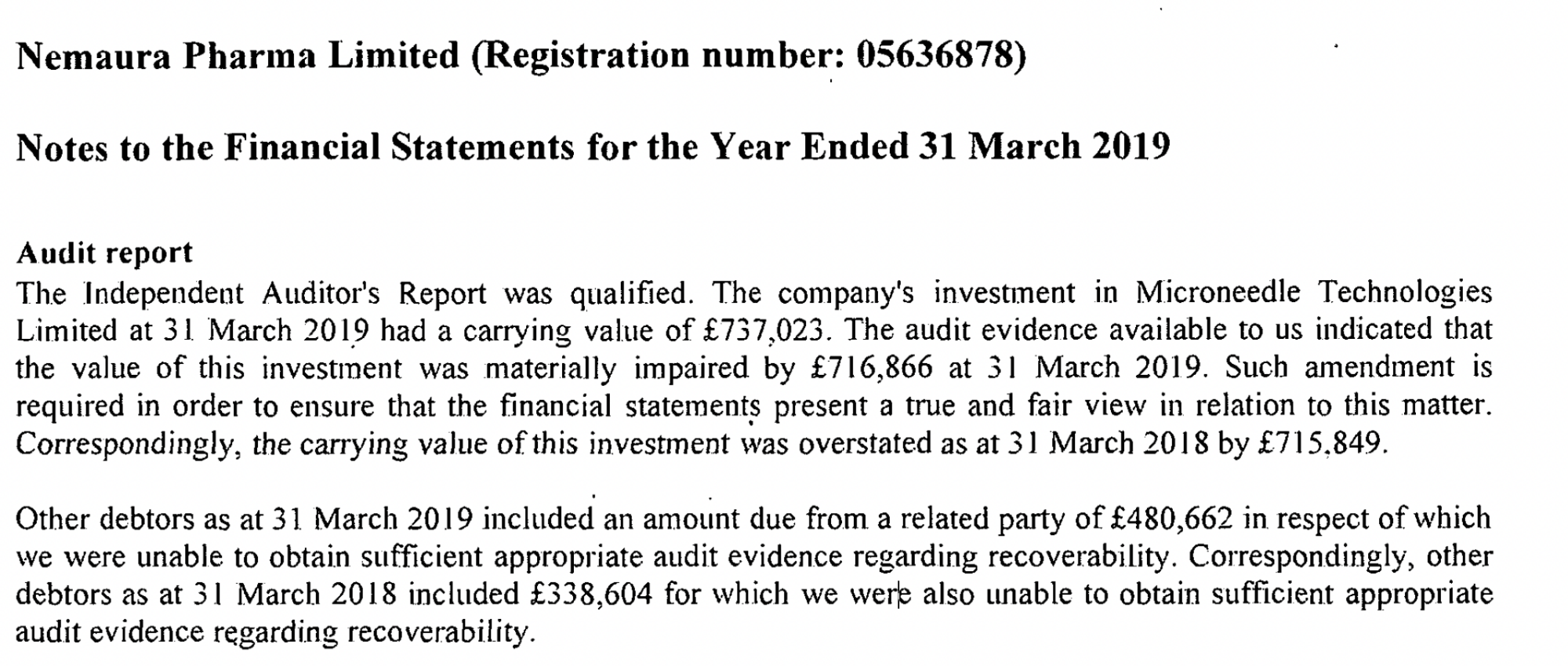

Nemaura Pharma Ltd’s accounts don’t look much like a pharmaceutical company’s accounts. Its accounts for 2015/16, when the largest R&D investment was made by the LLP, showed a company with £4.7m of cash but only £217k of intangible assets. It received significant income over the next few years, but by 2020 it had burnt through it all, without any increase in the value of its intangibles. This is odd for a pharmaceutical company – R&D expenditure is usually capitalised into intangibles.

In 2018, Nemaura Pharma spent £700k acquiring a company called Microneedle Technologies, owned by Messrs Chowdhury and Timol. By 2019 the company was worthless, and the £700k should have been written off. It wasn’t – so the auditors qualified the accounts. That wasn’t the only problem:

There is a web of related companies, often owned directly by Chowdhury and Timol rather than (as one would usually see) part of a corporate group. These companies also have oddities. For example, the LLPs all acquired an IP licence from an “affiliate” of Nemaura called NDM Technologies Ltd. But NDM’s accounts show no sign of this.

So what was going on?

These arrangements don’t make sense to us or the pharmaceutical industry contacts we spoke to. It’s possible that Nemaura was a normal pharma startup with an unusual focus on tax; it’s also possible that something else was going on.

A market failure

It is unusual to find a lawyer or accountant selling a tax scheme. We’d like to think that’s down to strong professional ethics, but there’s another important reason: if the scheme is duff (as it usually will be) then the accountants/lawyer will be sued. The market therefore provides a strong incentive for regulated professionals to provide sensible and prudent advice.

This doesn’t work for tax avoidance schemes like those sold by OneE.

Tax avoidance scheme promoters are in our opinion usually negligent – most tax advisers would say that their schemes have no reasonable prospect of success. However they typically operate through short-lived companies which are dumped by their owners after running the scheme. The main OneE vehicle, OneE Tax Limited, went bust in 2021 owing £70m to HMRC; the directors agreed to pay up £15m. So HMRC lost out twice – the tax lost on the schemes, and the tax lost by OneE’s own failures.

Most of the OneE and associated “pharma” entities have since failed to file Companies House annual returns and are in the process of being struck off.6 The website no longer exists and emails bounce.

So there’s little to be gained by suing a promoter. Nobody involved is regulated or insured, and they’ll just walk away and set up another company..

We said above that tax schemes are often sold by “introducers”: independent financial advisers or accountants who receive a large fee for the introduction. Accountants and IFAs are often regulated and insured, so in principle are attractive litigation targets. The problem is that, if the introducers are careful just to introduce the product (and receive their fee), and not to stand behind it, then they likely won’t have a “duty of care” and can’t be sued in negligence. Here’s an example where an accountant was sued for introducing a client to four doomed schemes, including the R&D scheme.7 There was found to be no duty of care.

And a further problem: tax disputes are very slow burning. It can be years between a client buying one of the schemes and discovering it doesn’t work. By the time it’s completely clear that the scheme failed, the limitation period for bringing a negligence claim will often have expired.

Needless to say, there is no prospect of suing the barrister who advised on the scheme (in this case, it seems, Robert Venables KC). He wasn’t advising the investors – he was advising OneE. We expect the investors were assured that an opinion exists, and they may even have been allowed to see it – but they can’t rely on it as a legal matter.

For these reasons, it is often hard in practice to sue anyone for the failure of these schemes, even though most tax professionals would agree that the schemes never had any realistic prospect of success.

This is a market failure. People are able to sell a duff product with no consequences from either HMRC or their own clients.

We all lose out as a result.

In principle these schemes should fail, with no tax lost. In practice, HMRC won’t always spot the schemes and challenge them, particularly if they’re not properly disclosed. Where HMRC does act, whilst it rarely if ever loses tax avoidance cases on substantive grounds, it fairly often has procedural losses (we’d estimate around 20% of the time). Sometimes that’s due to HMRC mistakes; sometimes that’s just the risk inherent in all litigation. And, where HMRC does challenge a scheme and win, it won’t always be able to recover the lost tax – the taxpayers may simply not have the money to pay it.

Fixing the market failure

One answer is for HMRC to pursue promoters. It does this to some degree, but resource and other constraints means that it hasn’t been able to stop the market in tax avoidance schemes.

An answer we’ve discussed before is criminalising the failure of tax avoidance promoters to disclose their schemes to HMRC, as required by law.

Another answer: ensure barristers are held to the same professional standards as solicitors and accountants, and end the likes of Mr Venables’ involvement in providing highly convenient but technically wrong opinions to people like OneE.

So here’s another solution: let’s fix the market failure. Create a market solution to tax avoidance by making it easier for clients to sue promoters:

- A new right of action should be created where someone is sold an aggressive tax avoidance scheme. How to define “aggressive tax avoidance scheme”? There are typically two signs. One is that the scheme should have been disclosed to HMRC, under the rules requiring disclosure of tax avoidance schemes, but wasn’t. Another is that the scheme falls foul of the general anti-abuse rule (GAAR), because it can’t be reasonably required as a reasonable course of action. Either of these should be enough to trigger a right of action.

- If HMRC then assesses the taxpayer for tax on the basis that the scheme doesn’t work8 then the taxpayer should have a right to recover their fees from the promoter and (where the promoter is a company) its human owners (“participators”). They should also be able to recover HMRC penalties.

- This will be a simple statutory indemnity rather than a new head of negligence.

- Where the taxpayer was introduced to the scheme by an accountant or IFA who received a commission, the taxpayer should have a right to recover that commission from the accountant/IFA. If the commission wasn’t disclosed, the taxpayer should also be able to recover any penalties.

- The limitation period for claims should be three years from the date of the HMRC assessment.

This would dramatically change the game. The prospect of personal liability will scare some promoters out of the business. A rational accountant/IFA should rethink mindlessly referring tax schemes to their clients (particularly if, as is likely, their insurers exclude this new liability from coverage).

It’s a private solution to a public policy problem, and which may just be able to achieve something HMRC has never managed – end mass-marketed tax avoidance schemes.

Many thanks to M for bringing this scheme to our attention, and for his initial analysis. Thanks to V and K for accounting analysis and to T and B for their pharma sector knowledge.

Footnotes

And if you hold 10% of the LLP you’d be taxed 10% of what you’d be taxed if you owned the whole thing. ↩︎

There were of course multiple clients, with £2m invested in the LLP and around ten separate LLPs, but the example will be easier to follow if I assume there was just one £26k client. ↩︎

These schemes no longer work for individuals because of the “sideways loss relief” rules, which stop an investor in LLP using its losses to shelter the investor’s other profits. However the rules (mostly) don’t apply to companies. ↩︎

We say “at least” because both the Corrigan and the LR R&D LLP judgment show 40% of the investments going in fees. The Corrigan judgment says total investments were £77m; and 40% of £77m is of course rather more than £10m. It’s not clear how these numbers reconcile. ↩︎

It’s good general advice for startups of all kinds to ignore tax and indeed most legal considerations until the business matures. Lawyers and advisers will just burn through cash and slow things down, and most mistakes are fixable. ↩︎

Tax avoidance scheme promoters tend to disregard company law. ↩︎

At the time of the judgment it was claimed HMRC hadn’t yet challenged the R&D scheme, so judgment was given on the basis of three failed schemes; that now looks incorrect. ↩︎

i.e. issues a “closure notice” ↩︎

21 responses to “How do promoters get rich from selling hopeless tax avoidance schemes?”

I see that OneE Group Limited is in liquidation after Corrigan obtained a winding up order against it last November.

Also I note that OneE Group Limited started out in life as “1st Ethical Group Limited” which doesn’t really seem to reflect what it has been doing.

That’s not quite right. One E went bust for the reasons explained by me here: https://www.accountingweb.co.uk/any-answers/one-e-tax-ltd

I agree. As you say:

“£70m unpaid tax from c£150m tax avoidance scheme profits all EFRBSed away in a few years with a c10% effective tax rate after a £15m ADR settlement (not at all a bad result for One E Tax Ltd’s owners if you think about it) should be a news story somewhere.”

Google avoiding tax is a big media story, but for reasons I don’t really understand, industrial-scale “tax avoidance” has never been a big story, although the amounts involved are likely larger. Disguised remuneration schemes of various kinds remain out of control. And “tax avoidance” in scare quotes, because all the schemes we’ve seen look technically indefensible.

See also my mini blog on this here: https://www.accountingweb.co.uk/any-answers/rd-tax-credit-avoidance-scheme#comment-1075784

Thanks – although I waited for the FTT before “railing” on the scheme. The fun point is whether the quantum of damages is affected by the hopeless nature of the scheme. On usual principles it won’t be, because (I expect) OneE suffered no loss from the failure of the scheme.

I think the more basic point is that if the scheme was hopeless in the first place then there should be no loss for damages for the scheme designer (from whom the scheme was allegedly pinched by One E) assuming this SC case does not help: https://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKSC/2025/10.html

Or perhaps that’s what you’re saying.

The fact that the usual 6-year limitation period for professional negligence claims concerning defective tax advice (etc.) is likely to apply from the time of its implementation notwithstanding there is a tax appeal thereto (that may or may not be successful) is not controversial and Integral Memory plc is cited in textbooks and other cases in support of that point. See: https://www.procedure.tax/6-time-limits. See also para 225 here: https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2017/1079.html

That little known limitation point is obviously very helpful indeed for tax avoidance scheme promoters as you correctly point out.

that is what I’m saying! Unless the defendant pleads ex turpi causa (i.e. there was an immorality/illegality) but they’re hardly likely to do that.

I expect the OneE vehicle has long gone, so (even aside from the difficulties with limitation period) scheme users can’t sue. Piercing the corporate veil and suing the individuals would be challenging. The civil claim for nicking the scheme didn’t have that problem.

So, they have tried it before many times with tax avoidance, and didn’t defend it in court.

They must have known what they were doing!

To my layman’s mind, why isn’t this treated as straight forward fraud and a criminal investigation opened.

Surely the role of Tax Counsel cannot escape scrutiny here. Regardless of the original instructions, the scheme was, at best, ambitious in terms of achieving the claimed tax outcome. Having been challenged, the baton is then taken up by a senior member of the same chambers who continued to argue in favour of this arrangement – surely a conflict? Presumably all were properly remunerated, at the expense of the investors/HMRC/taxpayers at large?

I make no criticism of the counsel who defended the scheme at the tribunal. They argued points perfectly properly, and dropped the inarguable circular funding point. Being from the same chambers is not a conflict.

If, however, the original scheme was backed by an opinion from counsel (perhaps Venables, perhaps someone else) then that’s a disgrace.

Dan, the way the story was told in Court by One E is as follows.

One E were operating a number of EBT/EFURB arrangements. Those were “coming under pressure” and they needed a new arrangement.

They looked at the Corrigan scheme and for reasons undisclosed (but almost certainly the cut of investor funds that the researchers wanted to do some actual work) and decided not to use it.

Instead they went to a (now) KC who they had used before and who “always had a number of ideas that we could use”. They claimed that the idea came from this KC although their own “medical research” company had existed for a long while before this – dormant.

So the KC was not asked to opine on a scheme thought up by One E but was asked for an oven ready scheme that they could market.

If I drive by accident for 2 seconds in an empty bus lane, I’m fined £180. If I defraud the taxpayer of £10m, nothing happens. With luck, this sort of moral imbecility will be bread and butter to Mr Starmer (though I understand he has one or two items on his plate first). As for the accountants etc, if you take the money, you take responsibility. Let it be criminalised for the theft it is.

So the original idea was thought up by Corrigan and Sherry, what was their purpose in disclosing it to the OneE people?

They seem to have done well out of a scheme that was destined to fail!

Steve, I think you may be a little confused here.

The “idea” created by Corrigan/Sherry was shared with One E because although those two had the technical knowledge and skills, they had no access to investors.

Their idea also arrived with a critical element that One E did not have, i.e. access to research scientists and facilities.

In the circumstances of the scheme it was necessary to now only own the right to use the IP but also to undertake the research = having the people/facilities.

As Dan says, the One E version used their own R&D outfit which had a lot of tax people and not many researchers. Any test asking if the company could exploit the IP was bound to end in a “no”.

My understanding is that the Corrigan version has never been tested by HMRC and therefore cannot be said to have been “destined to fail”.

The One E version with its lack of qualified staff, has been tested and has failed.

Great report as ever Dan

But the largest ‘facilitator’ of almost all of these avoidance schemes and downright thievery is actually, in my view, HMRC and by extension, the Government or Governments over successive years.

This is by having what seems to be a general policy in Government of ‘repay first, ask questions later’, which I am sure was not the case previously.

From obviously fraudulent Covid bounce back loans (and other Covid reliefs), student loans we read, to R & D, and this list of ‘freee money’ goes on and on, having this as a known (to all) policy is literally putting candy in crooks and n’er do well’s hands.

I bet they can’t believe their luck that someone would do this, yet successive Governments have authorised this, knowing the results. You’d have to be an imbecile to not see what you were doing with that policy.

For this, the Governments appointed head of the civil service gets a gong, when there should be a Post Office style public enquiry into HMRC and how they have turned a blind eye to theft for years, I think at least the last 10. Who authorised this in Government?

There should be an immediate end to pay first, ask later. This fuels the crooked advisors and their barristers, who don’t have to worry a jot about PCRT, as they are exempt.

I would imagine a LOT of the issues with HMRC’s capacity work wise and the delays caused to honest taxpayers and advisors could be solved by ending this as a policy, because likely most of the claims then would be genuine.

Any view on why the Government don’t do this? Are the crooked funds some kind of wonky quantitive easing, on the basis these crooks might spend some of the money in the UK and the wider sector?

From someone who used to work for Inland Revenue and HMRC but left in 19, I couldn’t agree more.

You would find those on the coalface didn’t like what was going on, but if you tried to raise the issue it somehow always got ‘lost’ you were considered a trouble maker, or didn’t understand the bigger picture!

I was glad to get out on good terms.

It was/is a mess.

You are absolutely correct that the “pay now, check later” was a gift to all tax planners, especially those who designed obviously “wrong” schemes.

I have seen (and still have) marketing materials and emails which trade on the fact that the investor can get a “free loan” from HMRC simply by making a claim.

And why?

Mainly because HMRC was hauled over the coals in Public Accounts Committee by its then chairperson, Margaret Hodge (not averse to tax planning of her own), for being slow to make repayments. In an effort to avoid (what I would say was a politically motivated) criticism, HMRC changed to pay now check later.

And the know the consequences of that.

A very interesting article and one that I very much agree with in some areas, less so in others.

First however a caveat. I was an “expert witness” in the Corrigan legal cases and suggested that the fees payable to him should be between a third and a half of the gross funds collected. The Judge went for 40%. I think his calculation was £77m, less commissions = Corrigan’s share. (Although there is some opaqueness here).

Second, a key issue here is that many advisers whose clients are looking for ways to mitigate tax are operating in waters way deeper than they can imagine. Your average High St accountant doe not have the bandwidth to understand and appreciate the risks in most tax avoidance schemes. They continue to “recommend” schemes however because it’s what their client expects and they get a commission. At the very least if a scheme fails, they should be required to return the commission to the client.

Third, HMRC has a portion of the blame here. In this case One E were well known purveyors of avoidance long before the R&D type schemes came along. DOTAS was never the answer and even then was hopelessly under resourced by HMRC. The professional bodies turned a blind eye and as far as I can see not one disciplinary action has been taken by any of them. It would not have been difficult for HMRC to have made their position clear to the pro bodies, agents and taxpayers – but they didn’t. HMRC then worsened their own position by failing to prevent companies disappearing. And now they expect taxpayers to pay for those errors. That is blatantly unfair.

Nobody involved in this type of avoidance – promoters, “businessmen”, taxpayers, HMRC, advisers – comes out with much credit but HMRC’s “remedy” is always that the taxpayer has to pay.

A very fair analysis of the issue. Back in 2017 I had an hour long conversation with Ipso-Mori as part of an HMRC Digital Growth study, that was looking into how businesses find dealing with HMRC and how HMRC could do things better. Towards the end of the call they gave me a hypothetical example of how a software author who had not registered with HMRC was not declaring his earnings and should have been registered for VAT – how would I recommend that HMRC dealt with him, when they found evidence from credit card transactions that he was dealing in this manner. I took the view that it was easy to get into this situation as a small business but that there needed to be warnings and a cut-off whereupon the business had to be brought into line – otherwise it was unfair for everyone. Towards the end of the call they asked me what I would like to see and I said that I wanted to see a number of members of the Tax Bar in red jumpsuits for the fraudulent tax advice that they had been passing out in relation to their avoidance schemes. I mentioned Jolyon Maughan and his then forthcoming VAT case against Uber as a shining example the other way – of how HMRC have been hitting unfortunate footballers whilst letting the real villains, the tax lawyers and accounting consultants off the hook. The operator said that she thought that my desire to see a number of members of the Tax Bar in red jumpsuits could well be the headline for their forthcoming report to HMRC. But naturally nothing came of this …

Keep up the good work Dan. Whilst your suggested solution is a step in the right direction, I’d also suggest looking at a change to increase the introducer’s responsibility, either financially, professionally or even criminally, as that would prevent a large number of introductions at source and prevent their clients believing such schemes have credibility by way of their introduction.

HMRC needs to go after the bigger players behind such schemes to provide a very public disincentive.

Great job on this analysis.