All three political parties say they can raise £5bn or more from cracking down on tax avoidance and evasion. How plausible is this?

UPDATED with the June 2024 tax gap figures

James Cleverly said on 26 May that the Conservatives would raise £6bn by clamping down on tax avoidance, £1bn of which will fund their national service proposal:

And here’s Rachel Reeves in April, saying Labour would raise £6bn:

So how plausible are these claims?

What is the tax gap?

The “tax gap” is HMRC’s estimate of the difference between the tax it should collect, if all taxpayers behaved perfectly, and the amount HMRC actually collect.1 HMRC’s total tax gap estimate is £36bn.2

The obvious first question is: who causes the tax gap? And the answer is not quite what we’d expect:3

The next question: what kind of behaviour causes the tax gap? Again, it’s a bit surprising:

So most of the tax gap isn’t the wealthy, or multinationals… it’s us. Most of it is small businesses receiving payment in cash and not filing properly (accidentally or deliberately). This is not a very politically convenient answer, but it is nevertheless the truth.

Now these figures are estimates, subject to numerous uncertainties, and shouldn’t be taken as absolutes; but they are also unlikely to be very far off the mark.45

So we can say with some confidence that neither Labour or the Conservatives can raise £6bn from clamping down on tax avoidance, because there probably isn’t £6bn of tax avoidance. But that’s not the end of the story.

So how can the tax gap be reduced?

Here’s a short agenda for closing the tax gap:

More resourcing

- There is now a widespread view, amongst individual taxpayers, business6 and the tax profession, that HMRC is seriously under-resourced. That is highly inconvenient for taxpayers (and sometimes much more serious than that). But it also means that some tax is not being paid: taxpayers are making mistakes, and HMRC is not helping them.

- It’s not merely that HMRC funding has failed to keep pace with inflation; its most experienced personnel have been moved onto other projects, particularly Brexit and the pandemic.7 This was probably sensible, but is having long term consequences.

- It is therefore in our view, and that of most other professionals we’ve spoken to (inside and outside HMRC) that providing more resources to HMRC is very likely to yield more8 than it costs, provided the funds are employed with care. So, for example, expanding helpline teams, compliance teams and creating special investigation units would seem likely to result in a positive return. Expanding internal and bureaucratic functions, less so. And, as in all organisations, it is likely that there would be pressure from internal stakeholders to expand internal and bureaucratic functions. Considerable care and skill may be necessary to avoid this trap.

- There will also be important benefits to individuals and businesses.9 This is not a zero sum game.

Treating “tax avoidance” as criminality

- There is an increasing amount of “tax avoidance” that is marketed to small businesses and individuals of relatively modest means, but that isn’t really avoidance at all. It’s a sorry mixture of incompetence and criminality.

- Attacking tax avoidance, broadly defined, could bring down those “failure to take reasonable care” and “evasion” figures.

- The vast majority of this “avoidance” isn’t promoted by the Big Four – it’s sold by dodgy outfits, some onshore, some offshore (particularly the Isle of Man). Their response to an HMRC challenge is often to walk away, leaving HMRC with nothing.

- The answer in our view is new powers enabling HMRC to pursue directors and shareholders of tax avoidance scheme promoters.

- We’ll be writing more about this soon.

Investigating tax avoidance and evasion more proactively

- Giving HMRC additional powers isn’t enough – HMRC need to be smarter and more proactive investigating tax avoidance and evasion.

- HMRC appears to be constantly playing catch-up with tax avoidance, only belatedly attacking structures that have been well publicised for years. HMRC once had special investigation teams that proactively uncovered and investigated avoidance; it no longer does. We receive many reports of avoidance schemes and tax scams from tax professionals across the country; we can investigate some, but sadly only a small proportion. This is something HMRC could do much more systematically and effectively.

- And, when HMRC does begin an enquiry/investigation, it does so in what often looks like slow motion, taking months to send out correspondence. This is, once more, highly inconvenient for taxpayers, but also risks losses for HMRC (both because limitation periods can run out, and because changes of personnel over time mean HMRC can, and does, drop the ball).

- In our view the loan scheme/loan charge affair was greatly exacerbated, and perhaps even caused, by HMRC not realising how prevalent loan avoidance schemes had become. By the time they realised, the situation was out of control. The same may be happening now with other forms of remuneration avoidance.

Closing “loopholes”

- The tax avoidance tax gap figure excludes arrangements that many people would call “tax avoidance” but isn’t strictly that at all, because it reflects intentional Government policy rather than a “loophole”.

- One example is the ease of avoiding stamp duty when you buy commercial real estate, another the simplicity of avoiding inheritance tax if you have a portfolio of AIM shares.

- It remains unclear why these “loopholes”10 continue.

Simplification

- Many of the “errors” and “failures to take reasonable care” reflect the complexity of the tax system, and the difficulties that ordinary taxpayers and small businesses can encounter from reasonably straightforward arrangements. Some of this complexity is inevitable, but some is not. We have entire taxes that have no reason to exist.

- £4bn lost to “legal interpretation” is an admission of policy failure. If there are areas where the law is unclear, those areas should be clarified (one way or another). £4bn of technically disputed tax each year represents a grotesque waste of HMRC and taxpayer resources.

- These measures would, we believe, reduce the tax gap, but probably not result in increased revenue (or decreased revenue). They would, however, benefit both the tax system and the country as a whole. Again, tax change is not a zero-sum game.

So are the claims that large sums could be raised plausible?

Yes – the claim is credible… but with the big caveat that simply increasing HMRC’s budget is unlikely to be effective to raise these sums. Careful targeting and management is required.

How do the Parties claims compare?

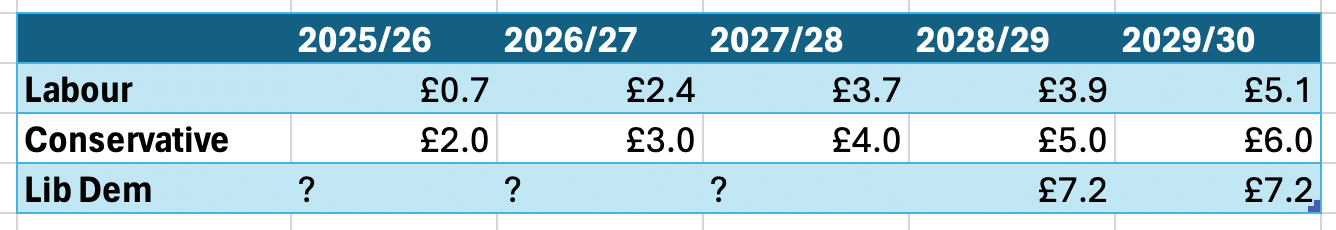

The three main parties have provided three very different sets of claims for how much revenue they could raise:

The Labour Party plan is in their “Plan to Close the Tax Gap” document. The Conservatives included a plan as part of their National Service press release. This doesn’t appear to be publicly available; we’re publishing it here. The Conservative figures weren’t in that press release, but are in their manifesto costings document.

The origin of the £6bn figure common to Labour and the Conservatives appears to be the head of the National Audit Office, who said earlier this year that £6bn could be raised by cracking down on avoidance and evasion. But he didn’t say how, or how much it would cost.

The Lib Dems just present the £7.2bn figure as 2028/29 funding in their manifesto costings document. They don’t give figures for earlier years. There is no published plan. I asked them about this, and their press office told me:

“We will invest an additional £1 billion a year in HMRC to tackle tax avoidance and evasion – more than Labour or the Conservatives. We are confident that this would enable us to raise an extra £8.23 billion a year by 2028-29 – an achievable and realistic figure. Jim Harra, Managing Director of HMRC, told the Public Accounts Committee that every £1 invested in cracking down on tax avoidance and evasion raises between £9 and £18. That would mean net revenue of £7.23 billion a year in 2028-29.”

Both Labour and the Conservatives also cite figures for historic ninefold returns from compliance expenditure (and, as above, the Lib Dems cite even higher numbers). However these figures are derived from historic targeted compliance measures which were relatively small. We are a little sceptical that they can be extrapolated to very significant billion pound measures, as is now proposed.

Comparing the Labour and Conservative plans: the Conservatives’ in large part reflects current Government initiatives (unsurprisingly). Labour’s plans are more detailed (as you’d expect, from an opposition with something to prove).

It is the Lib Dems who stand out: for having no plan, for claiming the largest revenues, and for assuming the revenues ramp up faster than others.

Many thanks to R, P and K for their input on this, and to C for help with the statistical elements.

Images from the BBC interview © British Broadcasting Corporation, and from Good Morning Britain © ITV, both reproduced here for the purposes of criticism/review.

Footnotes

Estimating the tax gap is a very difficult exercise, with numerous sources of error and uncertainty. HMRC does an impressive job to rigorous standards, generally believed to be the best in the world (most tax authorities only produce tax gap figures for VAT, which is a far simpler job given that it can be estimated with reasonable accuracy “top-down” from national accounts data). About ten years ago, HMRC’s homework was favourably reviewed by the IMF, who made various recommendations, most of which have been followed. More recently it was also reviewed by the Office for National Statistics. ↩︎

Other figures are sometimes quoted, but they are statistically naive. Richard Murphy produced a figure of £90bn back in 2019, but he did this by adopting a “top-down” methodology which, as HMRC and the IMF (page 46 here) have explained, requires a series of significant adjustments which Murphy does not make. Murphy’s estimate also fails the “smell test”. It requires us to believe HMRC are missing more than 95% of all tax evasion – that does not seem plausible given that HMRC conduct random audits of businesses (absent HMRC being corrupt, which is Murphy’s view). We’re unaware of any tax expert who believes Murphy’s approach is credible, and no country has adopted it. ↩︎

These figures are all from HMRC’s 2024 tax gap report, covering tax years up to 2022/23. ↩︎

It’s sometimes said that the estimates ignore offshore avoidance. This is not quite right, and there are two separate points here.

First, our work identified that HMRC does not systematically match up offshore account reporting with self assessment data. But that is different from saying that offshore is not included in HMRC’s tax evasion estimates. At most, HMRC’s estimate may be missing some evasion that would be identified by cross-checking HMRC’s sources of data. If so, the amounts are likely modest.

Second, HMRC’s tax gap does not include areas where something we might describe of as “avoidance” is actually permitted under the rules – for example the “double Irish” structure Google used prior to 2015. So in 2015 it was a very valid criticism to say that the tax gap estimates ignore multinational tax avoidance. However, things have changed since 2015. The many anti–avoidance rules implemented post-2015 make it much harder to see what “avoidance” remains permissible. Even the Tax Justice Network estimates (of which we’ve been very critical) show multinational avoidance costing the UK less than £2bn. This second criticism therefore feels of limited relevance today. ↩︎

Also note that the definition of “avoidance” doesn’t encompass planning that’s clearly permitted by the rules (even if many people wish it wasn’t). So, for example, the big tax advantages for non-doms aren’t a result of tax avoidance – they’re how the rules work. Ditto carried interest, avoiding SDLT on commercial property using enveloping, etc. ↩︎

See page 31 of the CBI report ↩︎

See paragraph 1.8 onwards in this National Audit Office report. ↩︎

We are sceptical of the Association of Revenue and Customs’ claim⚠️ that £910m of additional expenditure would result in £11.3bn of additional revenues. They reach this figure by looking at historic targeted budget increases, all at least an order of magnitude smaller than what the ARC is proposing (see page 49). The obvious response is – why stop there? Why not £2bn? The obvious answer is: diminishing returns. ↩︎

The Association of Revenue and Customs (the trade union for HMRC personnel) estimated⚠️ a £1bn per annum saving for business if HMRC response times could be improved; although the ARC has an obvious vested interest. ↩︎

Given they’re envisaged and permitted by Parliament, “loophole” is not really the right word, but we have been unable to think of a better one. Any suggestions gratefully received. ↩︎

![To: jeevacation@gmail com[eevacation@gmail com]

From: Peter Mandelson

Sem: Sun 11/7/2010 2 34 57 PM

Subyect: Fwd Rio apartment

Seat to mys bank manager Gratetul tor helpful thoughts trom my chief lite adviser

Sent from ims iPad

Bevin torwarded messave

From: Peter Mander iS

Date: 7 November 2010 [4 29 12 GMI

Subject: Rio apartment

P| ag awe dpeecussed Pan consdernne a purchase of an apartmentin Rion Ttisain](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Screenshot-2026-01-31-at-21.27.15-640x360.png)

Leave a Reply