Brooks Newmark & Co Ltd, run by former Conservative MP Brooks Newmark, lobbied for foreign PPE suppliers during the pandemic, but didn’t register under the Lobbying Act. It turns out this was entirely legal, thanks to a serious mistake in the drafting of the Act. This has created a loophole which means that lobbyists acting only for foreign clients don’t have to register their lobbying activity. That subverts the purpose of the legislation – the loophole should be closed.

The Transparency of Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014 (often shortened to the Lobbying Act) requires anyone carrying on a lobbying business to be registered, and to register the names of their clients. Brooks Newmark & Co Ltd, run by former Conservative MP Brooks Newmark didn’t register their lobbying for foreign PPE suppliers, and as a result the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists started an investigation.

Unfortunately the Lobbying Act turns out to have a significant loophole. The Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists has just ruled that, because Brooks Newmark & Co Ltd only has foreign clients, it doesn’t have to be registered.1

That create the perverse result that a consultant lobbying Ministers on behalf of UK clients has to register the clients, but a consultant lobbying on behalf of only foreign clients does not.

The Registrar’s ruling is, however, technically correct – because of a drafting mistake made back in 2014.

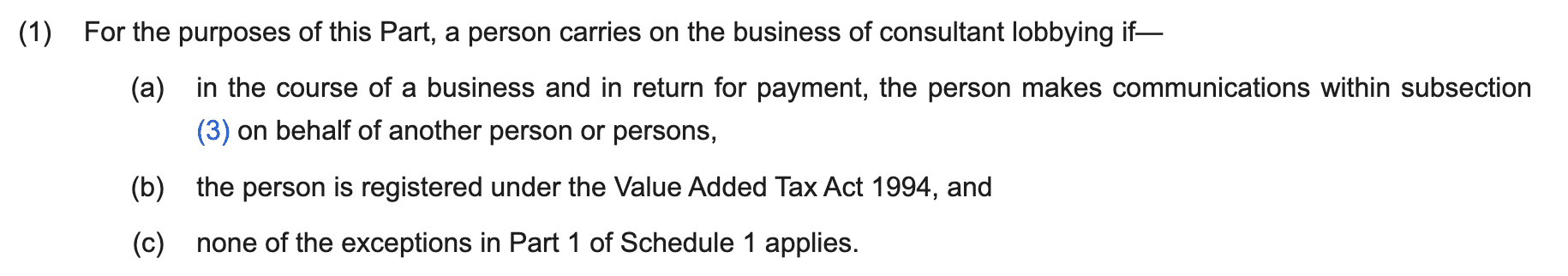

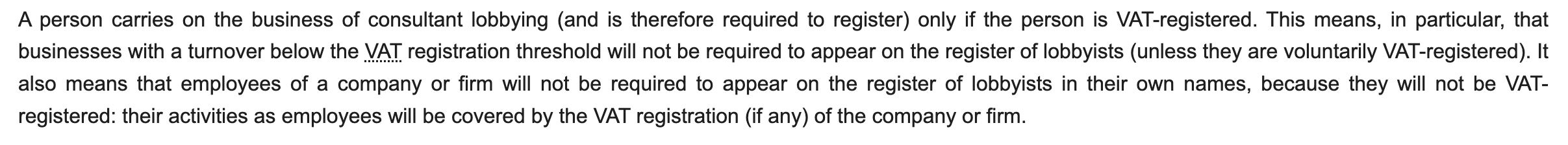

When the Lobbying Act was drafted, the Government took the defensible view that the Lobbying Act registration requirements should only apply to serious businesses, and not e.g. someone lobbying on an informal basis. The Parliamentary draftspeople clearly wondered how to define a “serious business”, and decided to refer to the existing concept of VAT registration. It’s well known that any business with an £85,000 turnover has to be VAT registered, and so they may have thought this was a neat shortcut:

It can, however, be dangerous to borrow legislation created for one purpose and use it for another, unrelated purpose. You run the risk of missing something important.2

In this case, the thing they missed was the “place of supply” rules.

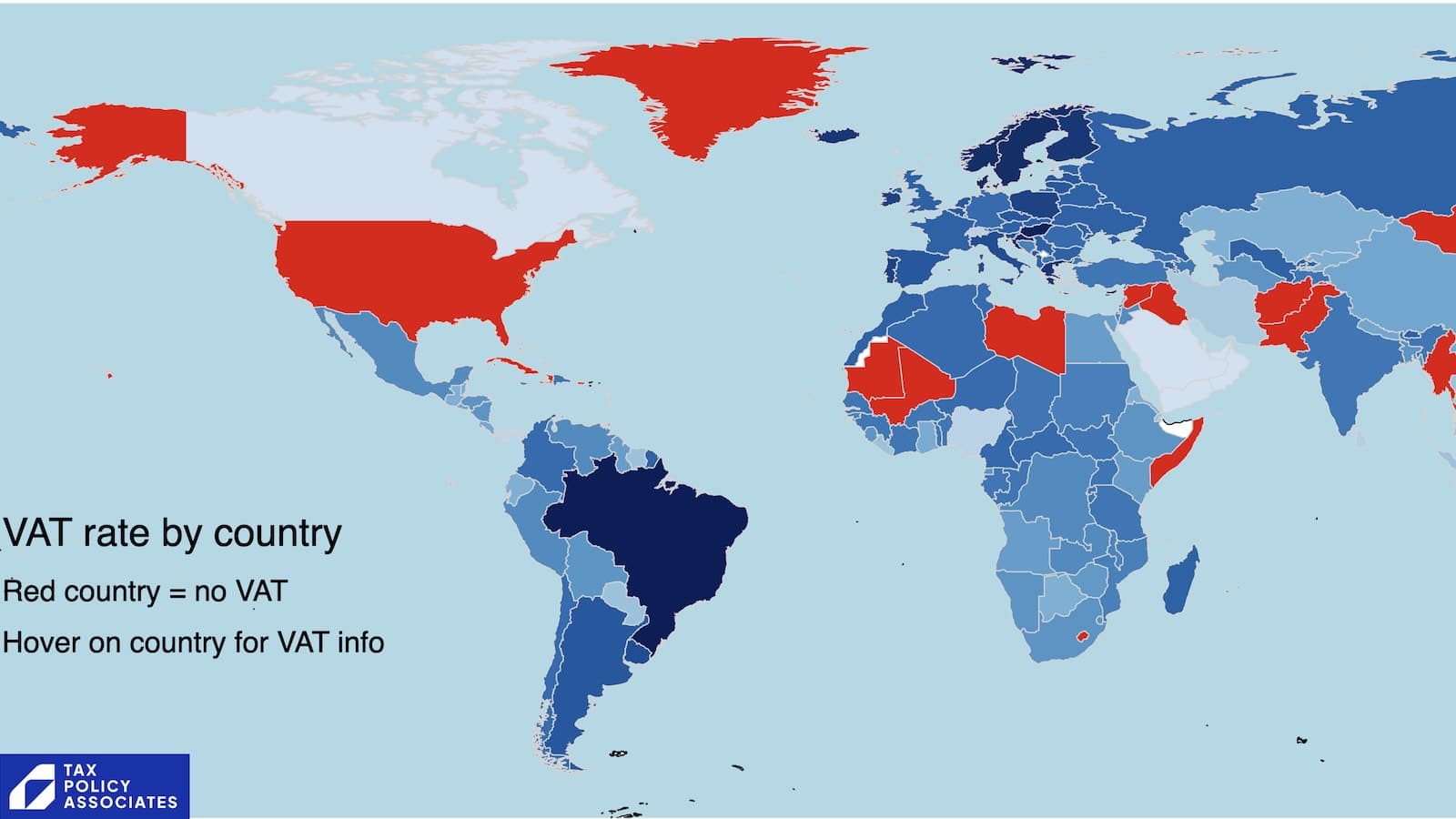

One of the nice features of VAT is that it doesn’t discriminate.3 A lobbyist selling consultancy services to a UK business is subject to UK VAT whether the lobbyist is based in Manchester, Monaco or the Moon. A lobbyist selling consultancy services to a French business4 is not subject to UK VAT whether the lobbyist is based in London or Lyon (but in the latter case there probably would be French VAT).

This means that if you’re a UK lobbyist whose only clients are foreign companies, individuals or governments, then you will never charge VAT. You’d normally register for VAT anyway, because that enables you to recover VAT on your costs (“inputs”), but you don’t have to – even if you make many £millions in fees.

The Parliamentary draftspeople unfortunately appear to have missed this5 – they assumed the only scenario where a lobbyist wouldn’t be VAT registered would be where they have less than £85k turnover. This is from the explanatory notes:

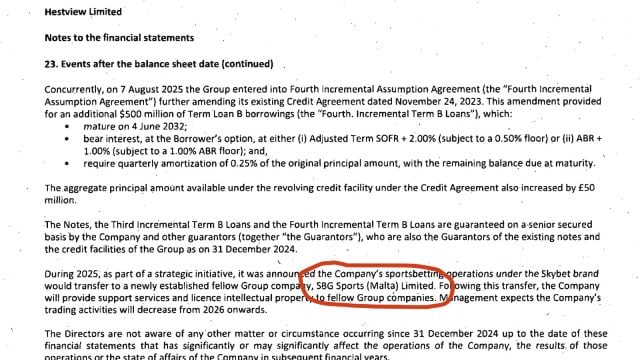

And that creates a loophole for consultants who only advise people outside the UK.6 A loophole that Brooks Newmark & Co Ltd qualifies for: because it only has foreign clients, it doesn’t have to register for VAT.

That’s not tax avoidance at all – in fact by not registering, Brooks Newmark & Co Ltd will be over-paying VAT. That makes me think this might have been deliberate Lobbying Act avoidance by Brooke Newmark & Co Ltd (as otherwise, why would they have chosen to pay too much VAT?).7

This now makes it easy for people to secretly lobby for foreign individuals, companies and governments.

If there’s one thing we know from the history of tax, it’s that if a loophole is revealed, and not closed, it will be ruthlessly exploited. If I was a lobbying company thinking of taking on a controversial foreign client, I could establish a new company to act for this one client.8 I’d pay a bit more VAT as a result, but never have to register the lobbying or the client. I’d be amazed if this doesn’t now happen.

But that may be the naive view – it’s possible that the loophole is already understood and exploited in this way.

The loophole should be swiftly closed. I believe this could be done easily by secondary legislation.9

Many thanks to L for letting me know about this case, which I otherwise never would have come across.

Footnotes

Carter-Ruck were acting for Brooks Newmark; in this case they appear to have been very effective ↩︎

It’s a particularly danger with tax legislation, because it has so many defined terms that appear helpful and straightforward, but are actually anything but. An example I often saw in practice was where a commercial contract had a concept of a company that’s “connected” to one of the contract parties. Someone would inevitably suggest borrowing the corporation tax concept of “connection“. The response from tax lawyers would generally be negative, because of the extreme complication and uncertainty that the tax connection concept would introduce. ↩︎

In the jargon, it is “border-adjusted”, and therefore permitted by WTO rules (see page 144 here) in the way a tax that discriminated against foreign sellers, or in favour of local sellers, would not be. ↩︎

Sometimes the rules are different for non-business customers, but in this case they’re essentially the same ↩︎

Richard Thomas has some very well-informed thoughts on this in the comments below; he thinks I may be being unfair ↩︎

The term “loophole” is generally used to mean an unintended result of legislation. The classical example would be where a devious taxpayer finds some way to exploit legislation in a way Parliament never intended, taking advantage of what in essence is a drafting defect. Modern anti-avoidance rules and common law doctrines mean tax loopholes are very unlikely to be found these days (or, more precisely, they are very unlikely to give you a tax advantage if you try to use them). Many things described as “tax loopholes” may be viewed by some people as undesirable but they are not unintentional, and so not truly “loopholes” at all. The Lobbying Act loophole, by contrast, absolutely is a good old-fashioned “loophole”. ↩︎

Alternatively it is of course possible they didn’t think it was worthwhile to register for VAT (which feels unlikely, given they appear to have had over £85k in revenue), or alternatively they just simultaneously mistakenly failed to register for VAT and mistakenly failed to go on the lobbying register, and they lucked out that the first mistake cancelled the second. It’s often a good rule of thumb that someone paying too much tax is as noteworthy as someone paying too little. ↩︎

I’d have to keep it outside my VAT group, and there would be irrecoverable VAT costs, including on intra-group supplies – but I suspect in some cases the secrecy advantages will overcome such tax disadvantages… indeed some clients might pay over-the-odds just to obtain secrecy. ↩︎

One could amend the VAT reference to include cases which would be registrable if the supplies were all made within the UK, but it’s much more sensible to drop the link to VAT altogether, and just impose a simple financial de minimis, plus an aggregation rule to prevent lobbying businesses being split into multiple entities to avoid registration. VAT is complicated, and in the future could change unpredictably. And using the VAT rule likely creates other opportunities to evade lobbying regulation, e.g. as Steve Woodward pointed out, splitting a business to multiple VAT registered entities. One of our correspondents, W, has also made the excellent point that it’s not obvious how you apply the current rule to a foreign business. All of which goes to show: it’s best to avoid tying unrelated legislation to a VAT concept. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Charlie G Cancel reply