There’s an updated and much more detailed analysis on CGT here.

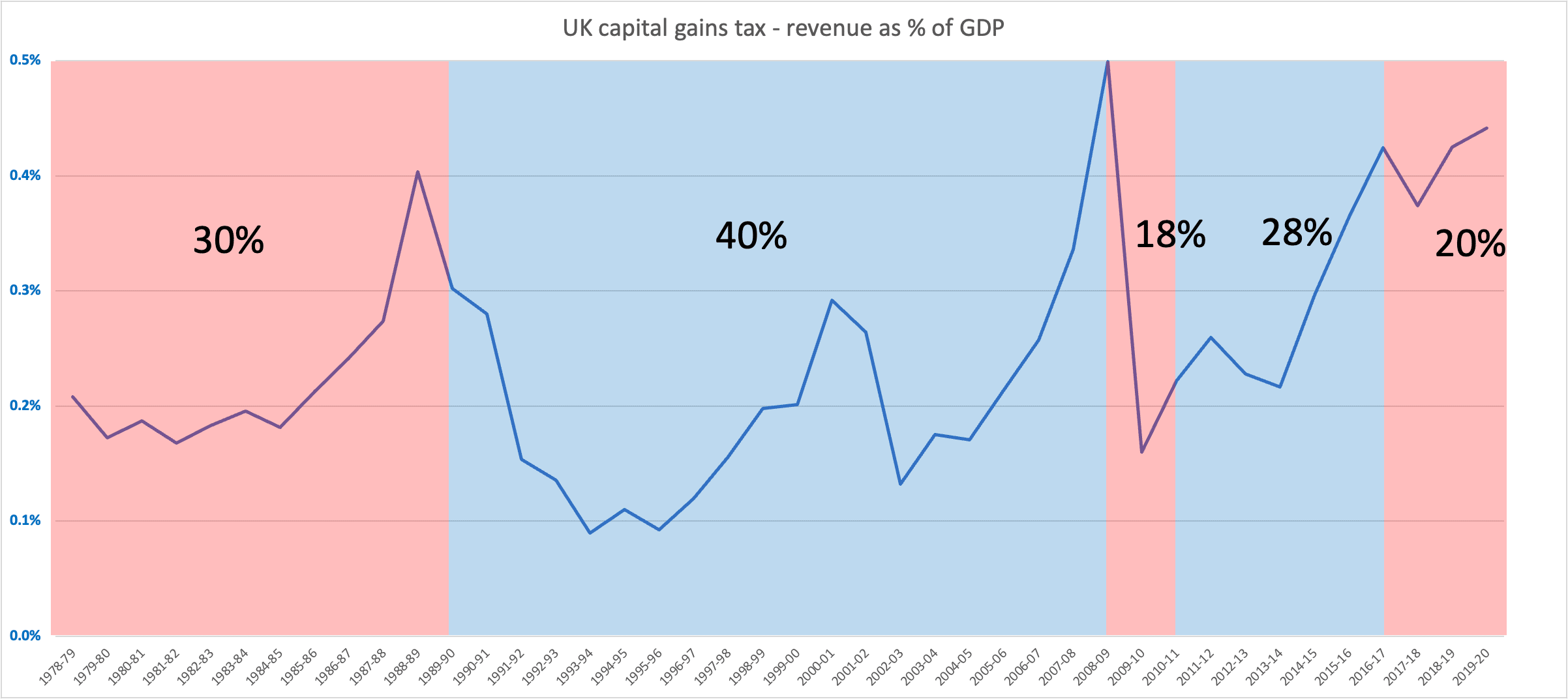

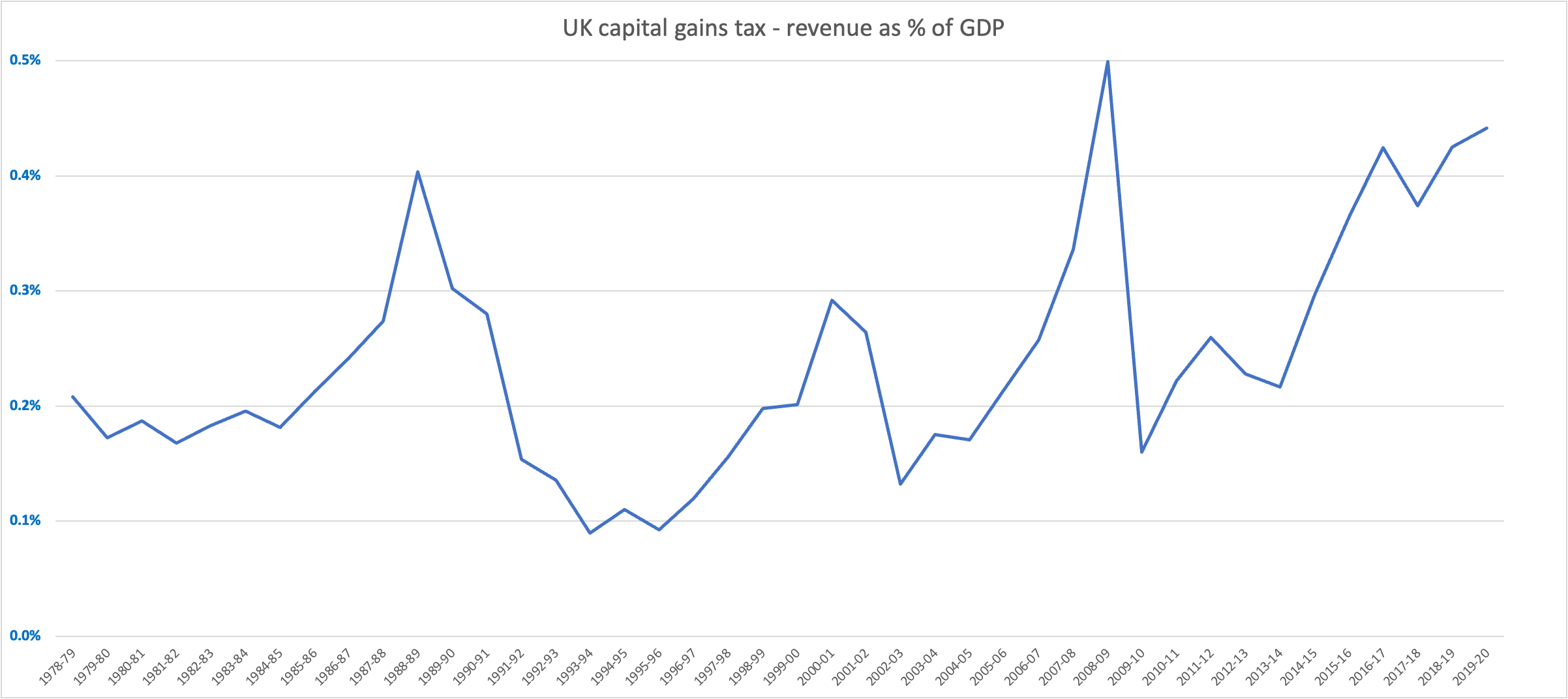

The chart above shows what happens if you plot UK capital gains tax revenues as a % of GDP since 1978. It looks mad.

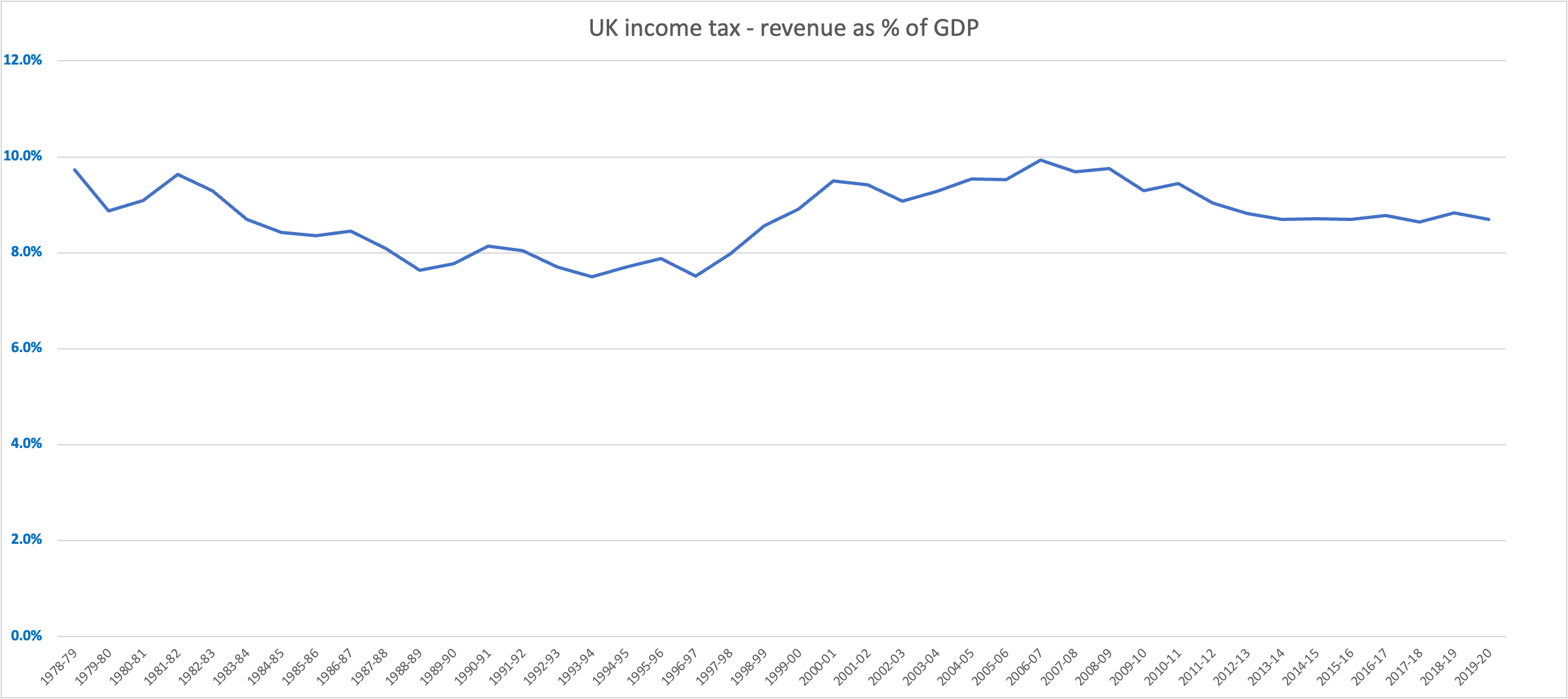

Income tax revenues, by contrast, look much more sensible:

What on earth is going on?

Politicians fiddling with the rules. Again and again. We start to see it if we overlay the rates:

When the rate is about to go up, people accelerate their sales to benefit from the current lower rate. When the rate is about to go down, people delay their sales until the rate has dropped. I went into some of the history of CGT here.

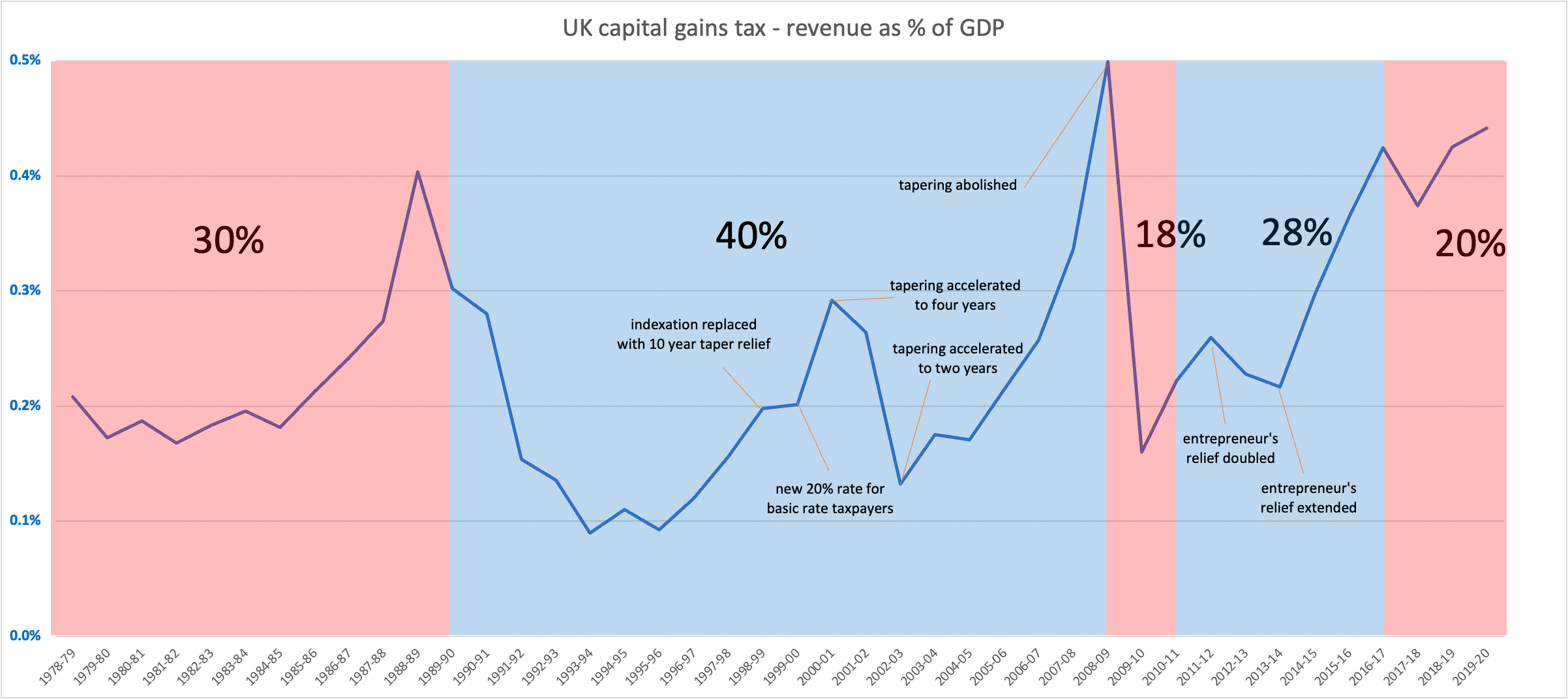

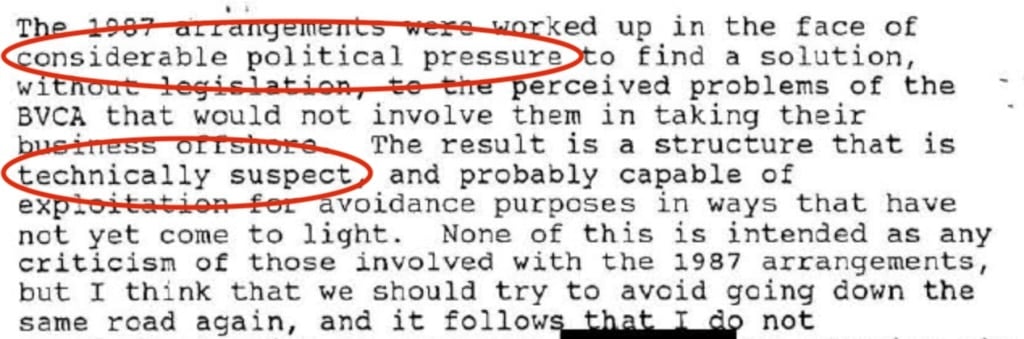

But that doesn’t explain all the peaks in the chart. For that we have to overlay all the constant messing around with the details of the rules:1

At this point some people can get very excited about the Laffer curve, and how the lower rates incentivised economic activity. I’m unconvinced. Even out the peaks and troughs and it’s not obvious there was any net change between 1978 and 2016. And, given the constant changes, it’s not obvious how any rational businessperson could make decisions based on the rate at the time.

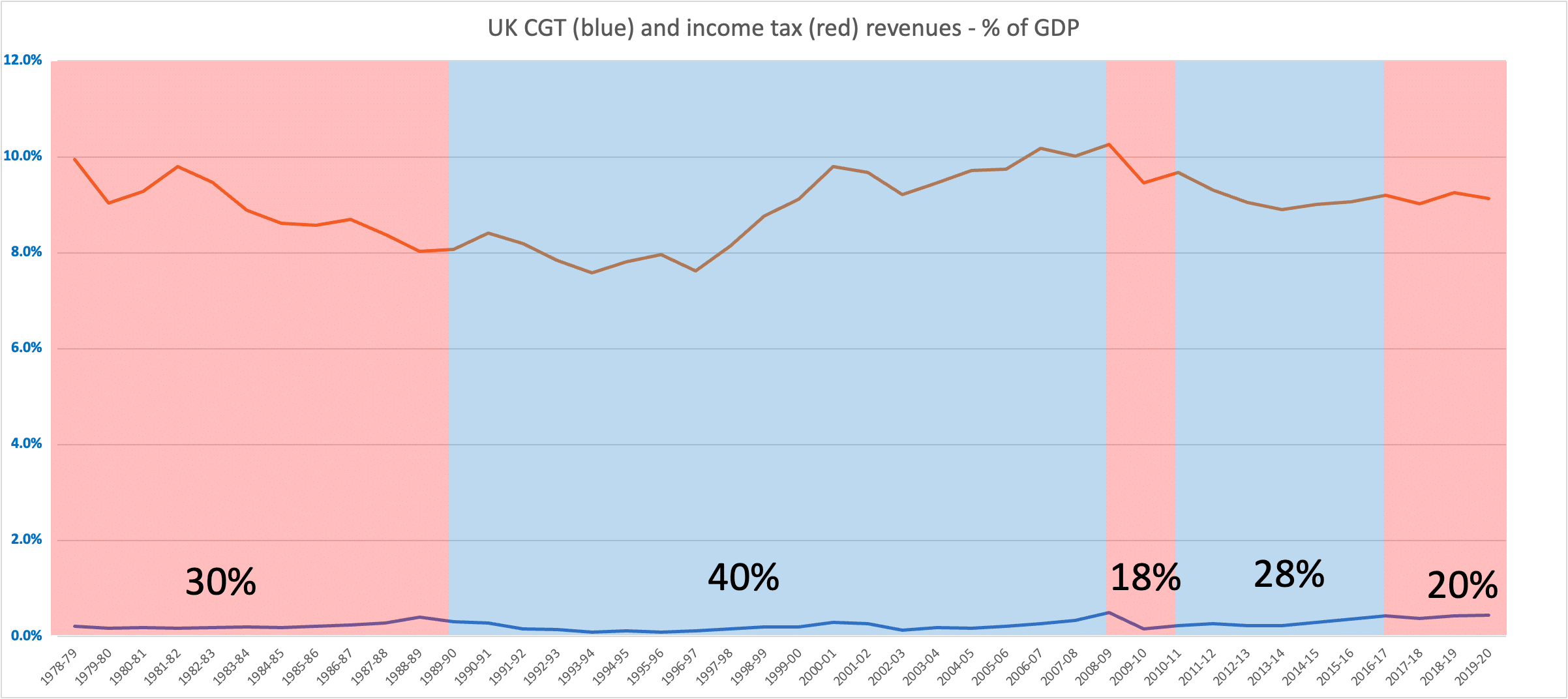

Some other people get very excited about the impact on inequality. I’m unconvinced. Put CGT and income tax onto the same chart, and we see quite how unimportant CGT is, and will always be (regardless of rate):

My view: the current system is dysfunctional. The large gap between the income and capital gains rates creates an unfortunate incentive to convert income (taxed at 45%) into capital (taxed at 20%). On the other hand, there’s no allowance for inflation, so long term investors find themselves taxed on a return that isn’t real. Rewarding avoidance and punishing long-term investment is not a rational outcome.

If some idiot made me Chancellor, how would I fix this?

- I’d close or eliminate the gap between CGT and income tax rates, but bring back the “indexation allowance” that stops inflationary gains from being taxed. Nigel Lawson got this right in 1988.

- I’d make the change immediate, to prevent a sudden spike in disposals.

- And then the important bit: I’d make a big show of announcing I wasn’t going to change any of the CGT rules for the rest of the Parliament. I’d resist the urge to keep bloody changing the rules, and enable investors and entrepreneurs to plan for the long term.

I wrote in more detail about the dysfunctional history of CGT, and the approx £8bn that could be raised by equalising rates, here.

Footnotes

This is greatly simplified. The number of changes when Gordon Brown was Chancellor were particularly egregious ↩︎

Leave a Reply