This is a version of the article published by the Sunday Times on 1 January 2023 – it summarises some of the themes I wrote about in 2022, and some more that I’ll be writing about in 2023.

Kwasi Kwarteng’s “fiscal event” last September was widely perceived as a disaster, but at its heart was a kernel of undoubted truth: there are features of our tax system that discourage growth — and we should fix them.

Here are five.

Income tax marginal rates over 60%

The boldest, and most criticised, element of the Kwarteng mini-Budget was to scrap the 45p top rate to “simplify taxes” and “incentivise growth”. The problem with this is that, even if you accept the premises of Kwarteng’s position, 45p is not even close to the highest marginal tax rate in the UK.

The marginal tax rate at any given income is the tax rate you pay on the next pound you earn. That’s crucially important, because it affects your incentive to earn that extra pound.

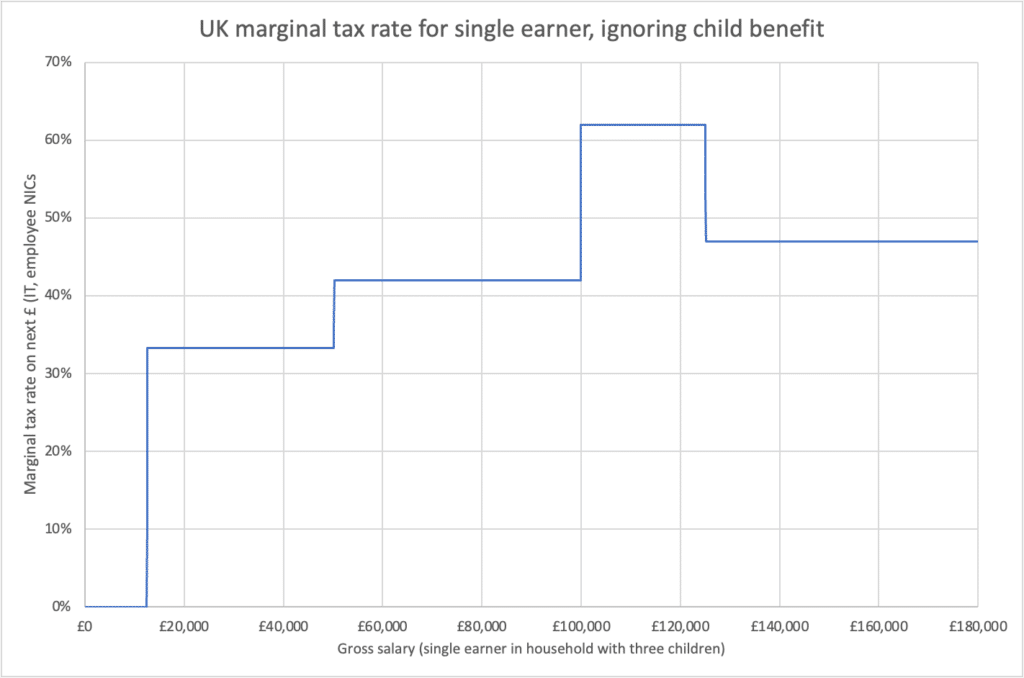

I’ve charted the marginal rate of income tax and employee national insurance for different incomes, and it looks like this:

This should immediately start ringing alarm bells. Why do the comfortably-off (£100-120k) pay a higher marginal rate of tax – 62%! – than those on really high incomes? Because at point the personal allowance starts to taper away – with every £1 of income earned about £100k, the personal allowance reduces by 50p.

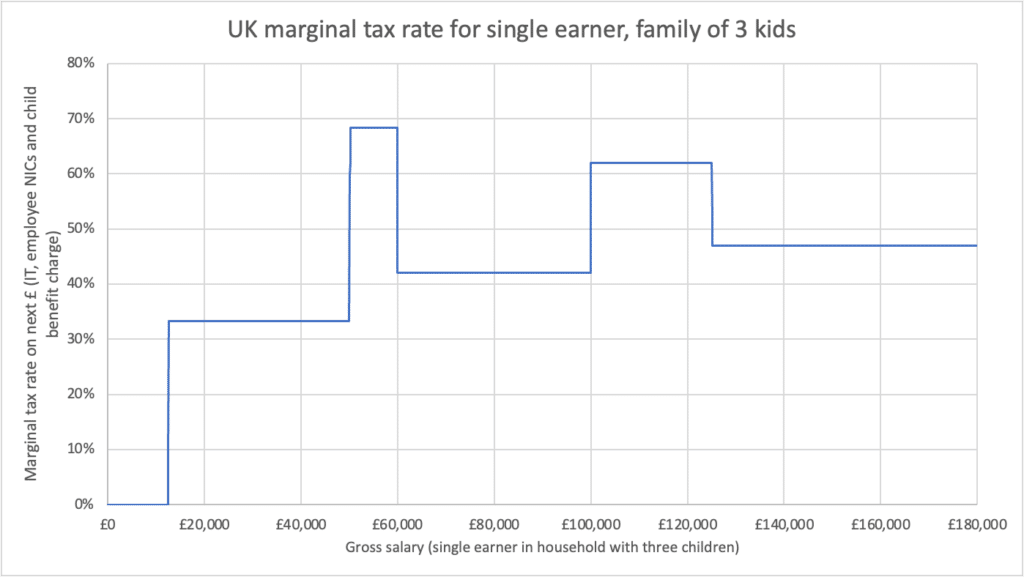

But we’re only getting started. What if you have three children all qualifying for child benefit? Well…

Child benefits starts to be withdrawn at £50,000 – resulting in a marginal rate of 68% between £50k and £60k.

Sad to say, we can make even that result look good if we throw in the effect of the Government’s much-heralded “tax free childcare” scheme. This entitles you to up to £2,000 per child. The catch is that it completely disappears if your earnings hit £100k. A couple can each earn £99,000 and they keep the benefit; but if one earns £100k they lose it (even if the other earns nothing).

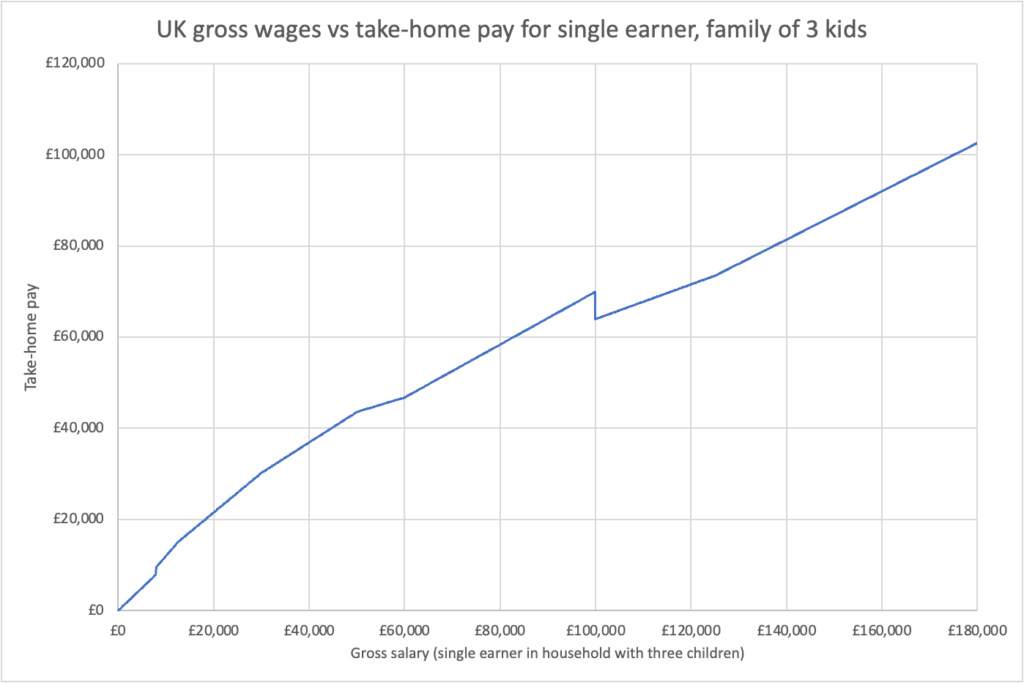

What marginal tax rate is that? Well, if you’re claiming tax-free childcare for three children, and currently earn £99,999, your take-home pay is £69,884. Earn £1 more, and your take-home pay is less – £63,942. That’s an infinite marginal tax rate, so slightly tricky to show in a chart. Instead, here’s a chart of gross vs net wages:

The ”dip” at £100k shows the drop in post-tax income, which isn’t recovered until you earn £20,000.

Put all of this together, and what does it mean?

It means that people who can control their hours usually think very carefully before putting themselves in the £50-£60,000 bracket, or the £100-£125k bracket.If they’re employed, they often make additional pension contributions, use salary sacrifice schemes, or find other ways to earn the money, but not pay tax on it. If they’re self-employed they often just stop working for the year. These are not good things for the UK economy.

And, worse still, all these tapering effects are triggered by one person’s income hitting the £50k/£100k trigger points. That means that the Smiths (who each earn £60k) are much better off than the Joneses (where she earns £120k, and he stays at home). The Smiths take home £93k after tax; the Joneses £75k. There are many reasons why the Joneses may have chosen that one of them should work and one not – it’s mystifying why the Government should slap an £18k penalty on their choice. The irony is that these accidental tax effects are so much larger than the deliberate tax policies Governments announce with much fanfare – the “marriage allowance” is worth a fairly pathetic £252/year.

Why isn’t there outrage about this? I think in part because people earning £50k or £100k feel it’s ungrateful or, worse, unBritish to complain about paying tax. And people earning less don’t want to hear the complaints. But it’s not about whether people on high incomes should pay more tax – it’s about whether they should pay more tax in a fair rational way, or in an unfair irrational way.

So a truly reforming Chancellor would declare war on marginal tax rates above 50%. We can do this without giving a handout to people on high incomes – the cost can be recovered by slightly increasing the top rate of tax. And the cost may be less than the Treasury historically thought, given that people are currently going out of their way to avoid paying these rates. And those on benefits also face ridiculously high marginal tax rates of up to 96% as benefits are withdrawn, creating a perverse incentive not to work (there’s outstanding work on this from the Resolution Foundation here).

Here’s the political challenge: politicians on the Right have to accept slightly higher taxes for some high-earners, and politicians on the Left have to accept slightly lower taxes for some others. Will they?

VAT punishing small businesses for growing

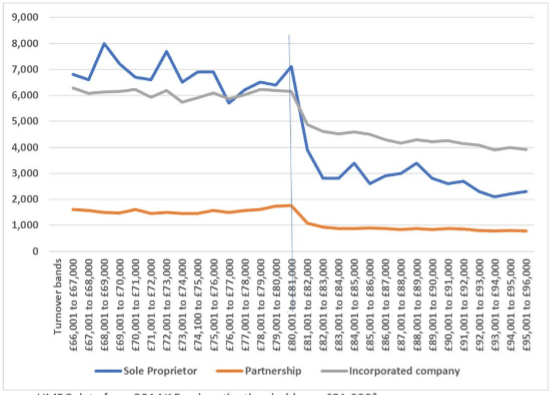

This chart should keep the Chancellor up at night:

It shows, for a given £ of turnover/revenue, how many businesses there are in the UK at that level of turnover/revenue.

You’d expect a reasonably smooth curve, falling from a large number of small businesses on the left side, down to a smaller number of larger businesses on the right. But we don’t see that at all – we see a dramatic cliff edge right on the VAT registration threshold (now £85,000). Businesses whose revenue hits the threshold suddenly have to charge VAT, meaning that – overnight – they must either raise prices or lose profits by up to 20%.

The chart tells us that many businesses respond to this by suppressing their turnover so it never hits £85,000. A cynic would say that they do this by taking cash under the table, and not telling HMRC. But there’s recent academic evidence that the cynic is wrong – this isn’t dodgy bookkeeping… businesses are genuinely holding back their growth as they approach the £85k threshold. The data is compelling, but I hear plenty of first hand stories too – plumbers going on holiday for the rest of the tax year; electricians not hiring an apprentice; coffee shops deciding not to open up another branch.

So here’s powerful evidence that the UK tax system has created a powerful brake on the growth of small companies…. some of which might, in time, grow into large companies.

There are two bad answers to this problem, and one good but difficult one.

The first bad answer is that we should raise the threshold from £85k. This is crushingly expensive, and doesn’t solve the problem… it just moves it.

The second bad answer is that the UK has one of the highest VAT thresholds in the world, and we should reduce it to the average (around £30k). Given the sudden impact that would have on tens of thousands of businesses, this would require a Chancellor to be brave-bordering-on-suicidal.

The good – but difficult – answer is that we shouldn’t have this kind of cliff edge threshold at all. And apps and digitalisation mean that now we don’t need to. Instead of VAT suddenly applying at 20% at £85k, what if it applied at 1% at £30k, and then slowly crept upwards, hitting 20% at £140k? We’d collect the same amount of tax, but without creating an incentive to stop growth.

Until recently, expecting anyone to operate a system like that would’ve been delusional, but the modern digital systems HMRC has put in place make it achievable. It would take years of planning, with HMRC having to provide free apps and compliance solutions to small businesses. The challenge is less technical and more political – politicians have to sell, and voters to accept, the idea that raising tax is necessary for growth.

Three dysfunctional land taxes

We have three taxes on land in the UK – council tax, business rates, and stamp duty. Three parts of a very broken puzzle.

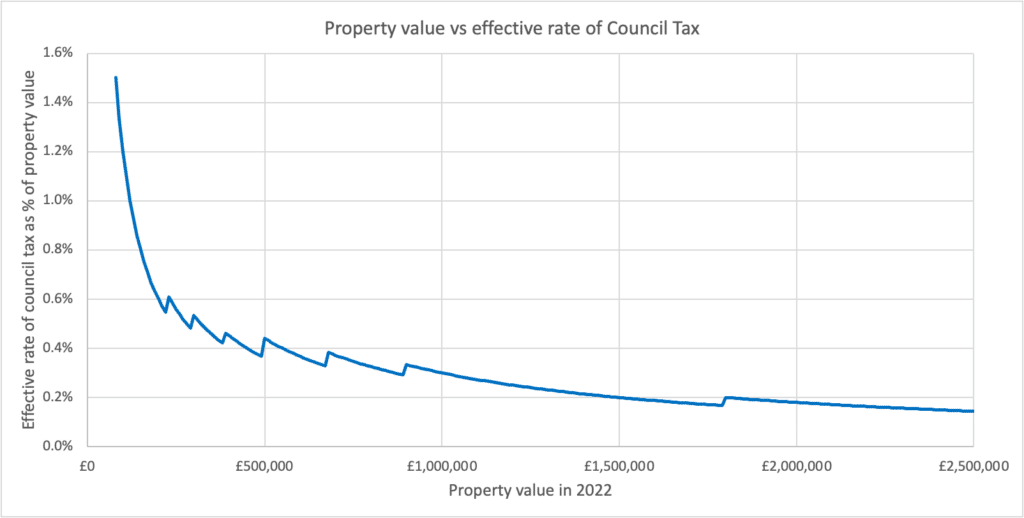

Here’s a chart showing how much council tax is paid as a % of the value of a property:

The more expensive the property, the less significant council tax becomes. That’s not how any tax should work. And in England, council tax is based on 1991 valuations that bear little relation to the housing market today.

Almost as bad is the equivalent tax for businesses – business rates.

The most common criticism of business rates – that it’s an unfair tax on retail businesses – is wrong. All the evidence shows that, in the long run, most of the economic burden of business rates falls on landlords (because rents are lower than they would be if business rates didn’t exist).

But there are other big problems with the tax. It’s based on the “rentable value”, but the rentable value is so frequently updated that you can end up with a situation, where rents have fallen, and the business rates haven’t caught up (which is in many cases where we are now). Another problem: business rates are taxed on the rental value of a property, taking into account whether it’s been improved. That’s a disincentive to invest in improving property. The answer?

And the final broken puzzle piece: stamp duty. It’s a good rule of taxation that we shouldn’t be discouraging transactions. Yet, as everyone who buys a house knows, that’s exactly what stamp duty does. It distorts the housing market and, by punishing people for moving in search of work, distorts the labour market too.

How can we solve the land tax puzzle? By scrapping all three broken taxes and replacing them with land value tax – an annual tax based on the unimproved value of land. Instead of acting as a brake on investment, it would encourage it. Moving house would become a tax-free event. The economic burden would fall on landlords, not tenants.

Land value tax has political support from economists across the political spectrum – all we need are politicians with courage to sell the idea that if we want to repeal bad unpopular taxes, then we have to create new, better, ones.

Corporation tax

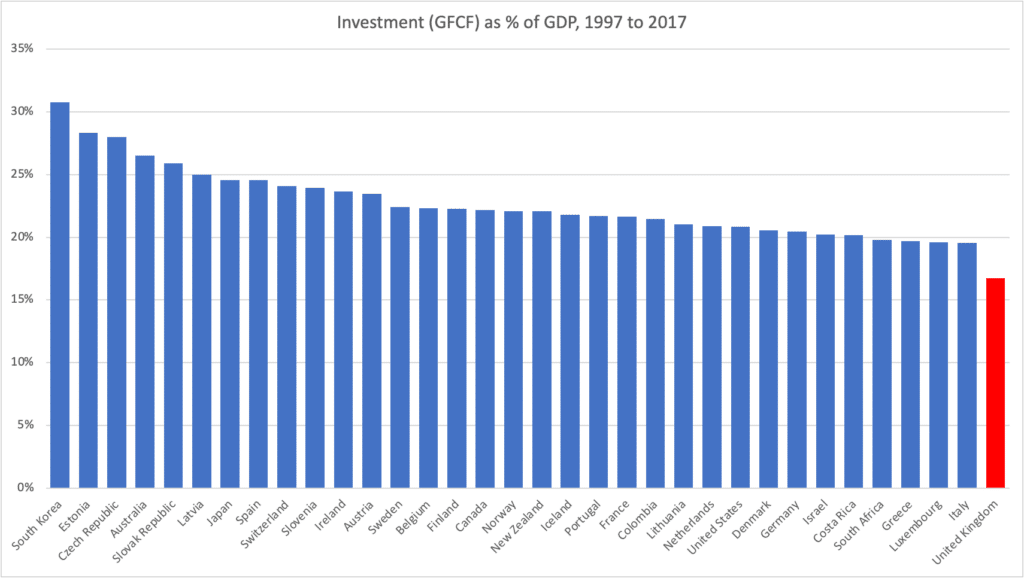

According to the Office for National Statistics, from 1997 to 2017, the UK had the lowest level of investment (as a proportion of GDP) in the OECD:

Is tax one of the reasons behind this?

It’s trite economics that businesses do things they’re incentivised to do. The problem is that UK tax relief for investment exhibits the two deadly sins of tax policy: it’s really complicated, and it changes all the time. This means that you’d have to be brave or foolish to make long term investment plans on the strength of today’s tax relief rules – you can’t be sure you’ll qualify, and you certainly can’t be sure the rules will be the same when your investment actually comes to fruition. Which is another way of saying that the tax relief rules fail to achieve their purpose of incentivising investment.

We need a radical solution. What if we didn’t have complicated rules governing what kinds of investments get tax relief, but just gave tax relief to all investment? Paid for by increasing the rate of corporate tax, so the reform was tax-neutral overall. And guaranteed to remain unchanged for the length of a Parliament – ideally with cross-party agreement that gives reasonable assurance for the longer term. Suddenly we’d create a powerful incentive to invest, made all the greater by the increased tax rate.

This isn’t my invention – it’s called “full expensing” and it’s supported by the CBI and economists across the political spectrum. But we’d need politicians – and voters! – to accept the counterintuitive truth that sometimes tax rates have to go up to encourage growth.

None of these issues are new. The Office of Tax Simplification has proposed reforming most of them. The problem has been that politicians prefer to duck difficult questions. Instead of adopting the OTS’ proposals, the Truss Government abolished the OTS. Let’s hope that, in an outbreak of Christmas cheer, Mr Hunt reverses that mystifying decision.

Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on Unsplash

16 responses to “5 ways to fix the UK tax system”

Slicing up a shrinking cake seems to be the problem to resolve by increasing productivity. The objective to slice a growing cake.

Industry leaders seem to have shorter times in post so are incentivised to get rich faster and if this impression is true would incentivise Directors to look at short term incentives. In extreme cases leveraged share buy backs would be popular especially in low interest periods. The impact on the growth would be negative.

These impressions would be worth investigating for if these behaviours are true then a strategy to restore incentives for growth need to be thought about.

A current danger seems to be nudging of DB pensions funds more towards bonds ( underwriting gilt issues,maybe) Another quick fix for increasing borrowing to consume.?

Thank you for explaining how income tax actually works. I had to stay at home to look after our 3 children with senco and health needs so I was unable to work but received no government financial help. This allowed my husband to earn well working 13 hour days earning £120k. He should be taxed the same as 2 married adults earning the same £120k, but he pays much much more. It punishes you for working hard and achieving well for your children’s futures, when they might not have the educational ability to earn much for themselves.

I have three queries, on which I would love to know your thoughts, or the limitations of what you would have a considered opinion on.

1. Land value tax: this sounds like a great centralisation of tax collection away from local councils, which would then need to be redistributed by central government. What is to prevent ‘pork barrelling’ upon redistribution? I appreciate that there is already an element of this with Business Rates following reforms by Osborn (I think), but would this proposed reform not compound those problems?

2. Capital Gains Tax: would it not make sense to bring this in-line with simplified income tax bands?

3. Would it not make sense to legislate, so that all revenue made in the UK from government contracts, or from monopolised industries like water, is subject to full UK taxes? Ideally with a punitive rate to discourage off-shoring of profits made off the back of UK taxpayers?

As an interested amateur I’m sure my thinking here is overly simplistic, but negative income tax seems like a way to support very low earners beyond the personal allowance. With a more progressive — or maybe even smoothly varying — rate of income tax it doesn’t seem like there would be any reason to set a floor of 0% on the marginal rate.

It’s always interested me as an idea, but I know too little about the benefit system to have a view on how viable it would be.

Great article, and I agree with most of it, but would take issue with your piece on corporation tax.

In my experience incentives based purely around timing differences (e.g. capital allowances) are beloved of economists but do little to drive investment by businesses in the real world. Why is that?

1. Many, perhaps most, larger businesses are much more focused on earnings (EPS, a P&L/accruals concept measure) than they are on cashflow/timing differences. That’s because their investors are more interested in sustainable earnings than in cashflow. Can be different of course for a highly leveraged PE-backed business or – more arguably – for a smaller startup. But for larger and particularly quoted businesses, earnings rather than cash are ‘king’. So a lower CT rate is much more of an incentive than an accelerated deduction. When I talk to large businesses (including those represented on the CBI), they almost universally would prefer a lower rate to an improved capital allowances regime. Interestingly, representatives of small businesses tend to share that view.

2. The practicalities of how investment decisions are made. Of course many/most businesses will look to some kind of NPV model when assessing capital investment. That said, in my experience the models (even in very large businesses) are pretty unsophisticated when it comes to tax. There are so many other factors at play that tax is typically consigned to a single data point, namely the applicable CT rate in order to calculate the post tax return. Unless you’re already one of the largest, most capital intensive half dozen businesses in the country, you typically don’t have much or anything in the way of assumptions around the timing of tax deductions – so in practice most models are already over-estimating the speed with which they would obtain tax relief on investment & that wouldn’t change with a move to full expensing.

3. The ONS measure is focused principally on fixed assets investment. Given the nature of our economy in the UK (more services/FS and less hard-capital intensive), it’s unsurprising that our stats for this kind of investment as a share of GDP are low. In the theory the ONS measure does attempt to capture investment in software too, but presumably only to the extent it is capitalised, whereas much software investment is already expensed – and that is increasingly the case with the move to SaaS. What the ONS measure doesn’t cover at all is investment in people and skills, which are arguably much more important for the health of the UK economy going forward, and for which full expensing already exists.

4. Tax rates matter more than timing differences when it comes to international comparisons and where multinationals choose to make their investment decisions (again, in people just as much as in ‘hard’ assets). In my experience tax is seldom the sole or most important factor in such decisions but it is part of the overall cost equation. And again that is a P&L measure of cost, using a comparison of headline tax rates rather than timing of tax relief.

Overall, therefore, I think it would be a big mistake to prioritise accelerating the timing of a limited portion of investments at the expense of raising the headline rate.

I’ve heard the argument that we’ve had a low(ish)/competitive headline rate for some years now and our investment as a proportion of GDP is still “low” but I don’t think that is a particularly valid argument. Firstly, because the ONS measure of investment is only a (small) part of the story and secondly, as we don’t really have a baseline against which to compare this. As mentioned earlier, tax is just one part of the equation; the UK has been suffering from a number of other disadvantages e.g. poorly trained workforce, political instability, Brexit factors (perceived and real) etc. If we had had a higher tax rate and narrower tax base/accelerated timing relief, I suspect those investment figures would have looked even worse.

(Sorry if this turned into an essay, by the way, but this is a really interesting and important area, thank you for raising it!)

These are really interesting points – thank you.

Thanks for the thoughtful article, Dan. I’ve experienced the effects of these policies first-hand over my career, as an employee in the affected brackets, a freelancer operating under a Ltd company, and (separately) a trading business owner. Here’s my take on “economy growing” initiatives based on this collective experience:

1) Abolish IR35. In the modern international gig/remote work economy, the 9-5 salaried employee is one option of many. Let people swap the comfort of a permanent, domestic position for no sick/maternity/paternity/statutory pay if they want. Not every role is amiable to permanent/fixed employment. Trying to tax every penny the same denies the outsized risk some people take to earn a living.

2) Incentivise exports. If you want to grow an economy, encouraging selling good/services overseas. Right now, it’s the opposite– it’s easier for me to *buy* overseas than trade. Zero rating VAT on foreign tourist purchases is a start.

3) Zero rate domestic B2B sales at the POS. There’s no reason we should be giving HMRC a 3 month interest-free loan on VAT we’re only going to claim back anyway. Domestic companies are at a disadvantage; I don’t pay VAT on international purchases, yet I’m forced to charge another company (who may not be VAT registered because they’re under the £85k threshold) an amount inclusive of VAT.

4) Automatically enroll all companies (Ltd and self-employed) in VAT. What makes VAT particularly troublesome is that it’s opaque; many consumers see an advertised price, and have no idea that 20% of it goes directly to the government. Reducing the registration limit to zero prevents artificially stymieing revenue because every pound is treated the same. Further, every company could claim back VAT at the POS on all purchases. Rid the bizarre trade-off of having to choose between lowering consumer prices yet paying more on expenditure vs. charging 20% more but claiming back costs.

5) Retain the personal allowance for everyone, irrespective of income. The point of the allowance is to provide a starter amount that everyone is entitled to earn, regardless of circumstance, before paying into the shared pot. The ‘penalty’ for earning more is the increased tax brackets when one graduates beyond the basic income bracket. Removing the allowance is a double dip — you pay more and get even less.

6) Offer “head of household” tax brackets, regardless of marital status. Many, many single earning families still exist. Some of this is due to circumstance – childcare costs make it unfeasible for anyone earning less than £30k to consider it a viable/fair consideration. For others, it just works better. Whatever the reason, life is already exceedingly expensive- unlike the previous generation, houses aren’t a 3x multiple of income anymore, and one salary rarely stretches far enough (even for oft-demonised 6 figure earners). The bias toward independently taxed earners is unfair and often contrary to the realities of building a family in the modern world. All benefits calculations should have the option of treating income as earned by all adults in a household, removing the ridiculous penality that currently occurs if one person earns a relatively large salary and another earns nothing.

7) Set a long-term strategy. The biggest problem in Britain is that you can’t count on it. The country is fundamentally uninvestable in if in one budget you’re claiming a reduction in tax and investment incentives, and then two weeks later you propose a 180 reversal. Likewise, if the country is so divided along party lines that everything the current government implements is likely to be reversed by the next government, where’s the assurance that the decisions we make today will still match the reality 2 years from now? There needs to be clearer, long-term, centrist agreement that can gather cross-party support and not the partisan, bickery, point-scoring, fundamental divide we see in politics today. Without political reform, we are likely to flip-flop between two philosophically opposed economic models for decades to come.

8) Consider a universal basic income now. AI is here and only getting better. What happens when millions in the workforce can be replaced? This is a serious question that we should be working on now.

Have you any info on the distributional effects of the land tax proposal? Seems like the better off would be the ones losing out? If there are lots of net losers further down the income distribution then the politics of it are going to be tough.

Two observations about Corporation Tax.

1) With its unusually high services component it’s surely questionable whether ‘investment’ has the same meaning in the UK as it would in a largely manufacturing economy. Perhaps your graph should also include spending on education and training indicating investment in human capital??

2) As you point out tax relief might well stimulate investment. One could ask whether such investment would be productive – a large tax ‘subsidy’ might encourage reckless or wasteful investment. Further, low interest rates over the past years don’t seem to have stimulated investment, despite substantially lowering the discount rate.

Thanks Dan, excellent article. Your section on personal taxation is very interesting and absolutely correct. I work in the NHS which is clearly in crisis at present, and could really use doctors to work additional hours. However, I know many of them who are approaching the 100-125k tax trap and this, along with pension tax rules, completely discourages them from taking on extra work. They all ready work above and beyond their contracts, so why would they work more, and see their families even less than they currently do, for so little take home pay in return. It’s bonkers.

I don’t think a variable % of VAT would ever be workable, instead you could lower the thresholds then have a tapering rebate against the VAT paid by those affected to reduce the cliff edge

Economically that’s an equivalent proposal; technically of course very different. Lots of careful thought required as to how to implement – the important thing is that we should be discussing how to solve what looks right now like a very serious problem.

Intrigued to know how a phased VAT rate would work? Imagine – early in the year a trader might expect to have turnover of £X, Implying a VAT rate of N%, but later in the year see his turnover increase taking him into a higher rate, but he has already invoiced N% to clients in the early part of the year – can he go back to them for more? Hardly – he’d have to absorb it, and this is not something I see an app being able to fix.

Perhaps he could have an “option to tax” as real estate landlords have, so he could opt to tax VAT-registered clients, who can recover it on their own returns, and opt out for domestic clients who aren’t VAT registered? Then as long as his opted portion accounts for at least as much as his final-annual rate, he has nothing further to pay. It wouldn’t increase the tax take, just manage the cliff edge in a way that doesn’t leave the trader holding the baby.

I agree – lots of difficult questions here, and I don’t pretend to have all the answers, or indeed many of them. Serious thought would be required – but the current problems are bad enough that we should start that thinking!

Thank you for a very readable, sensible article.