This is an updated version of an article first published in 2023.

What’s the very short answer?

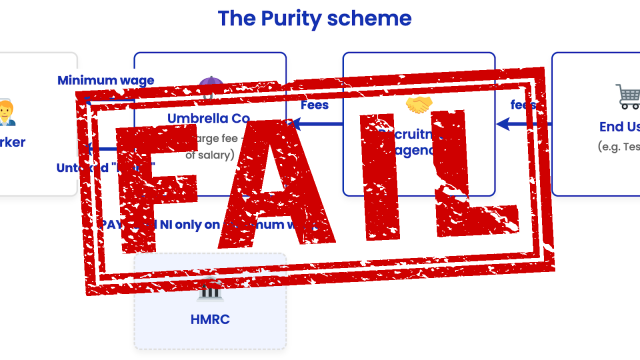

It’s this:

(click to make bigger)

But what is the legal definition of “tax avoidance”?

There isn’t one.

More precisely, there isn’t a single legal definition of “tax avoidance”. If there was, life would be easy: we’d pass a law saying that if you do tax avoidance, you lose, pay lots of extra tax, and maybe go to jail as well.

If you ask a lawyer for advice on a complex arrangement or transaction, they will go through many rules, some of which they may call “anti-avoidance rules”. But they won’t write an analysis on whether the arrangement is “tax avoidance” because there is no legal test that works that way.

So why am I bothering to use the term at all? Because if you do something most people regard as tax avoidance then some or all of the following will happen:

- People won’t like you. Newspapers will write bad things about you. Consumers might even stop buying your products.

- You will probably be caught by one of those “anti-avoidance rules” – approximately 64,000 have been enacted by Parliament over the years. So what you hoped would avoid tax in fact won’t avoid anything at all. The phrase used by most practitioners and HMRC is that your scheme “didn’t work”.

- Even if you brilliantly escape the letter of the 64,000 anti-avoidance rules, you’ll run into the problem that judges really, really, don’t like tax avoidance (and haven’t since the late 1990s). So if you end up in court, the judge will probably magic some way for you to lose anyway (perhaps applying “common law anti-avoidance principles”). This annoys some legal purists, but doesn’t make me particularly unhappy.

- For all these reasons, if HMRC finds out about your tax avoidance, they will challenge it, and – almost all of the time – they will win. You will end up paying the tax you tried to avoid, very possibly other tax you picked up along the way, plus interest and (potentially) penalties of up to 100% of the tax due.

So I would strongly advise individuals and businesses not to do tax avoidance, or anything that HMRC will consider is tax avoidance.1

No really – what is “tax avoidance”?

The conventional view – shared by most advisers, academics and HMRC – is that tax avoidance is using “loopholes” or other features of the tax system to save tax (“obtain a tax advantage”) in a way that wasn’t intended by Parliament. This is not a legal definition, and probably can’t be – but it’s a workable rule of thumb.

So here are some things that are not tax avoidance, even though (in the usual meaning of the term) you are “avoiding” tax:

- Investing through a pension or ISA. Yes, it avoids tax, but that was absolutely intended by Parliament. Not tax avoidance. Anyone who says otherwise is very silly.2

- Buying chocolate cake. Cake has 0% VAT. A chocolate-covered biscuit has 20% VAT. If you are pondering whether to buy a cake or a biscuit, and buy a cake because it’s cheaper, you are (in the most literal sense) avoiding VAT. But this is a legitimate choice – Parliament has drawn a stupid line in the sand, and you’re free to walk either side of it. The world is full of such choices, and none of them are tax avoidance.

- Avoiding 39.35% income tax on dividends by investing in a “growth” company/index, so most of your return will be capital gain (taxed at only 20%, at least prior to the Budget). Another stupid line in the sand, but not tax avoidance.

- Being genuinely self-employed3 Self-employed people get to claim deductions for expenses. More importantly, there’s no 13.8% employer national insurance (because there isn’t an employer)

It seems profoundly illogical that not everything that avoids tax is “tax avoidance”, but it is also correct. All of these examples fit neatly in box 1 of the infographic at the top of the page – “normal tax planning”.

And here are some things that are definitely tax avoidance:

- Investing £10,000 in a film and claiming £50,000 film tax relief (i.e. so you had £50,000 of taxable income; you now have zero taxable income, saving around £20k of tax). Where does the other £40,000 come from? It’s borrowed from a bank, but actually goes round in a big complicated circle, so it’s as if it doesn’t exist. Absolutely tax avoidance. Didn’t work.

- Paying £95,000 to magically create £1m of tax relief through a complex transaction which threw large amounts of money round in a circle, supposedly linked to a second hand car business. Didn’t work.

- Avoiding £2.6m stamp duty on the purchase of the Dickins & Jones building on Regent Street by taking advantage of a complex interaction between the partnership and subsale SDLT rules. The taxpayer thought it was a simple and elegant scheme. The Court of Appeal took about two pages to kill it.

- Having your wages paid to an offshore trust which then makes a “loan” to you (scare quotes because it never has to be repaid and there’s no interest on it, so it’s no more a loan that it is a bicycle). Instead of paying income tax on your wages, you pay either nothing or a very small amount. Tax avoidance. Doesn’t work4. Amazingly, people still flog these schemes.

All these schemes had two things in common: they were trying to achieve a result that wasn’t intended by Parliament, and they were highly complex and roundabout ways of achieving something that should be simple (buying a house; receiving a wage; investing in a business).

Also, none of them worked. Almost no tax avoidance schemes work these days – meaning that the courts decide that the “trick” the taxpayer thought they’d found didn’t actually avoid tax at all.

So each of these is in box 3 of the infographic (“failed tax avoidance”).

This seems easy enough – what’s so hard about defining tax avoidance?

How about these examples?

- Incorporation. A plumber makes £50k/year. He sets up a company and starts working through that, paying himself dividends from the company. Nothing much changes, but he now doesn’t pay Class 4 National Insurance contributions – saving him about £3k/year. This is incredibly common.

- Salary sacrifice. A [insert sympathetic employee of choice] earns £60,000. She’s offered a £5k pay rise – but that will be taxed at an almost 60% marginal rate, as she loses child benefit. So she uses a “salary sacrifice” scheme to make larger pension contributions, and gets the benefit of the £5k (eventually) without a high marginal tax rate.

- Listing. A large plc is about to issue bonds to European pension funds. At the last moment, a tax lawyer spots that the bonds are unlisted, and so will be subject to 20% withholding tax – nobody will buy them.5 The obvious solution is to list the bonds, even though it serves no commercial purpose. A withholding tax exemption will then apply. Was the decision to list tax avoidance? It certainly avoided tax.

- Taxable presence. A French champagne company sends a Paris marketing team on a promotional tour of the UK. They worry they might accidentally create a taxable presence in the UK, meaning that a chunk of their profits become subject to UK corporation tax. So they ask their accountants to draw up a list of dos and don’ts for the team to follow. Is that tax avoidance? It could avoid a whole bunch of tax.6

I would say none of these cases are tax avoidance, because in each one a person is making a choice that is anticipated and permitted by tax legislation, and which has actual consequences. They are all in box 1 of the infographic at the top of the page (“normal tax planning”). Other people may disagree.

And then we get to the really difficult edge cases, where no tax system can produce sensible answers. Like exotic financial products and buying children’s clothes.

- Sometimes it’s obvious what was intended by Parliament – e.g. your earnings should be taxed. The problem with complex financial products and other esoteric commercial products is that the legislation is often so arcane, and the results completely unintuitive, that the question of whether you’re in box 1 (“normal tax planning”) or box 2 (“successful avoidance”) becomes meaningless.

- Much more difficult is VAT on clothing. It’s usually subject to 20% VAT, but children’s clothing has 0% VAT. The only person liable for the VAT is the retailer, and they determine the correct rate following HMRC guidance which mostly looks at sizing and whether clothing is sold as children’s clothing. Some smaller-sized women can save 20% of the price by buying🔒 children’s clothes (I know someone who does this; it’s not just an urban myth). This result really wasn’t intended by the legislation, but calling it “tax avoidance” feels daft.

So you can’t realistically define tax avoidance in a legally robust way – and that’s why, as far as I’m aware, no country has managed to do so successfully.

Doesn’t the GAAR define tax avoidance?

Since 2013, the UK has had a “general anti-abuse rule” – the GAAR. Note the term is “anti-abuse” not “anti-avoidance”. This isn’t an accident – it reflects the impossibility of comprehensively defining avoidance. Instead the GAAR applies only where a scheme is so outrageous that it can’t reasonably be regarded as a reasonable course of action to take. This is called the “double reasonableness test“.

The GAAR has in practice had very little effect, as the courts were happily striking down avoidance schemes for 57 different reasons well before the GAAR came in, and they’re equally happy to continue doing so. HMRC have in practice been using it as a shortcut, to save all the time/cost of taking a case to trial. There is an excellent article on the GAAR here, from Tax Adviser magazine.

But we can be reasonably confident that, even if the four “definitely tax avoidance” examples above had somehow made it through every other anti-avoidance rule and principle, the GAAR would have kiboshed them. However, it wouldn’t have touched my four “maybe tax avoidance” examples – and that’s sensible (because otherwise no plumber would ever know if it’s safe to incorporate, and that would be unfair, and the resultant uncertainty would be bad for all of us).

Doesn’t some tax avoidance work?

Perhaps. Here are some things many people would say are tax avoidance but which normally work7:

- A US digital company makes lots of money from customers in the UK, but as it has only a very limited presence in the UK, it pays only a very limited amount of corporation tax. Its huge profits should be taxed in the US, but because the US tax system is broken, they’re largely not (particularly prior to US tax reform in 2017). Most laypeople people would say it’s tax avoidance; most advisers would say it isn’t. I’d say it’s a big problem either way: we’ll see in a year or so how effective the new OECD global minimum tax has been at changing things.

- A company reducing its profits by borrowing from its shareholders. Fair enough that interest paid to a bank reduces a company’s taxable profit, but we also permit this for interest paid to shareholders. There are now rules that limit the tax benefit, but there’s definitely still a benefit.

- Non-dom excluded property trusts. Being a non-dom is a perfectly legal way not to pay tax on foreign income for 15 years. After that, they’re fully subject to UK tax. But if they’d prefer not to be then, just before the 15 years is up, they can put their foreign assets into an “excluded property trust”, and keep them outside UK tax forever. Sure seems like tax avoidance, but it’s an inevitable consequence of the ways trusts are taxed, and so not something HMRC can usually challenge. The 2024 Budget seems likely to change that.

- There’s 5% SDLT when you buy commercial real estate. So most commercial real estate is held in “special purpose vehicles” – offshore companies whose only activity is holding the real estate. Then instead of selling the real estate, you can sell the shares, with no SDLT. Seems fair to say it’s avoidance, but it’s an inevitable consequence of the way SDLT works, and so there’s no chance of HMRC challenge.

None of these would be stopped by the GAAR, which is reasonable given that each is a choice that Parliament has intentionally8 made available to taxpayers.

I think these are within box 1 of the infographic at the top of the page (“normal tax planning”). Others will disagree, and say they are within box 2 (“successful tax avoidance”). But that’s just a moral/ethical/political judgment – no legal or tax consequences follow from which of those two boxes these arrangements are actually in.

What is the difference between tax avoidance and tax evasion?

The classic tax lawyer answer is: “the thickness of a prison wall”9. Like most classic lawyer answers⚠️, it isn’t of any help at all.

In theory, the difference is simple. Tax evasion is dishonestly failing to pay tax10. Usually there is an element of concealment or deception. Tax evasion is illegal – i.e a criminal offence, punishable with jail time and an unlimited fine.

Here are some classic examples – and let’s assume for now that in each case the people involved know full well what they’re doing:

- Having “cash in hand” income you don’t declare to HMRC. Easily the most common form of tax evasion.

- Opening a Monaco bank account in the name of your dog, using it to receive “bungs”, and deliberately not declaring the bung or the bank account to HMRC. This is a hypothetical example.

- Claiming film tax credits on expenses that never existed.

- Doing an elaborate tax avoidance scheme, but where the key element is deceiving HMRC about the value of some shares.

- Doing an elaborate tax avoidance scheme, where a key element is lying about the residence of a company.

- Holding large amounts in an offshore trust, which you don’t disclose to HMRC⚠️ even after you are caught evading tax on other offshore accounts.

These are all clearly tax evasion, and people can and do go to jail for them. It’s box 5 of the infographic (“tax evasion”).

If they didn’t know, and it was an accident (even a negligent one) they’re in box 4 (“non-compliant”), and may pay penalties, but escape criminal sanctions.

What is “dishonesty” in this context?

So it becomes very important whether someone acted dishonestly. In practice that means: whether HMRC think they can prove dishonesty to a jury.

The modern approach to “dishonesty” applied by UK courts is to ask whether the conduct was dishonest by the standards of ordinary decent people (regardless of whether the individuals in question believed at the time they were being dishonest). The leading textbook of criminal law and practice, Archbold, says:

“In most cases the jury will need no further direction than the short two-limb test in Barton “(a) what was the defendant’s actual state of knowledge or belief as to the facts and (b) was his conduct dishonest by the standards of ordinary decent people?”

It used to be different. A jury had to be persuaded not only that an objective person would think I was dishonest, but that I knew I was dishonest.11 So I could say that I was acting in line with what others in the sector were doing, and thought it was perfectly fine. That no longer helps me if a jury decides that objectively I was being dishonest.

What’s the difference between tax avoidance, tax mitigation, tax shelters and tax planning?

All are undefined vague terms that can mean what we want them to mean.

I usually use the terms like this, but you should feel free to disagree with me:

- Tax mitigation = a polite term for tax avoidance

- Tax shelters = a term that the US tax avoidance industry has successfully used for years, so that US media usually refers to “tax shelters” (which sound nice!) rather than “tax avoidance schemes” (which don’t).

- Tax planning = chosing to walk on on one side of a line that has been drawn by Parliament, and being careful not to step over the line.

So is tax avoidance legal or illegal?

It depends:

- John and Jane both enter into the same tax avoidance scheme. John believes it works. Jane knows it doesn’t, but thinks HMRC won’t spot it. HMRC do spot it, challenge the scheme, and win.

The result, in theory, is that John and Jane both filed an incorrect tax return, and so owe the tax, interest and (if they were careless) penalties. They got their tax wrong, and that’s not illegal.

But Jane was dishonest. She committed tax evasion and so did act illegally. The question is: can HMRC prove it?

Here’s another, and more realistic, example:

- Catherine devises an elaborate “tax avoidance scheme” which she knows in her heart-of-hearts has no chance of working, but by the time HMRC come round to challenging it, Catherine (and her fees) will be long gone.

- Catherine flogs the scheme to hundreds of taxpayer clients, assisted by an opinion she somehow obtained from Thelma, a tax QC.

- Thelma is politically hostile to the idea of taxation, and takes positions on the legal analysis which very few tax advisers would share. In her heart of hearts, she knows the courts won’t agree – but she thinks the courts are wrong.

- The clients all believe the scheme works.

This is definitely tax evasion – Catherine was dishonest, because she knew the scheme didn’t work. Thelma was probably dishonest (because her advice was not caveated with “this is my view but you should be aware that the courts will likely disagree”). The question is whether we can prove this.

Other tax advisers may say the scheme had no reasonable prospect of success, and we can suspect that Catherine and Thelma knew this, but Catherine will say she had an opinion from Thelma. Thelma’s advice is probably legally privileged, so neither HMRC nor the courts will ever see it. If they did, Thelma will say she was advising on the basis of her good faith view of the law.

I think a jury might well say that, by the standards of ordinary decent people, it’s dishonest to take tax positions that 99% of tax advisers would say are wrong. But HMRC has, to my knowledge, never tested this, and there’s never been a prosecution with facts anything like this. I would like that to change.

But the key point: it’s incorrect to say that tax avoidance is per se “legal” or “illegal”. Much of the tax avoidance I’ve seen in the last few years falls into the Catherine/Thelma category. It’s really tax evasion, but there’s no prosecution.

Who will end up out of pocket here? Catherine, Thelma or the clients? Usually the answer is: the clients. HMRC recovers the tax from them. Possibly they try to recover penalties from Catherine, but there’s a good chance she winds up the business and walks away. Thelma is untouched.

So why do almost all articles about tax avoidance say “there’s no suggestion this was illegal”?

I’ve no idea.

Do companies have a legal duty to minimise their tax?

Directors have a broad duty to promote the success of their company, and tax is just one of the many factors directors should consider in making a decision. A director may well be failing in their duties if they blunder into a large unnecessary tax charge. But in no sense does this create a duty to minimise tax, anymore than it creates a duty to minimise employees’ pay or maximise consumer prices. This is very clear under the Companies Act 2006, and was clear enough under the old common law rules.

Why do so many people appear to think this is a live issue? I’ve no idea. In 25 years of practice, I didn’t once come across a client or lawyer who thought directors had a duty to minimise tax.12 So this appears to be a political/ideological point rather than a legal one.

Did [politician I don’t like] commit tax evasion?

One consequence of political polarisation is an eagerness to use terms like “tax evasion” to describe what is almost certainly a mistake, if the taxpayer in question is a politician who we don’t like.

Nadhim Zahawi certainly got his taxes wrong. There was at one point good reason to believe that Angela Rayner go her taxes wrong (although she says HMRC has now confirmed that she didn’t). I once made a small mistake on my own tax return.

It is, however, not a criminal offence to pay the wrong amount of tax by accident. It’s not even a criminal offence to pay the wrong amount of tax because you were careless (although that can trigger penalties).

It’s only a criminal offence if you fail to pay tax deliberately and dishonestly. There was never any evidence that Zahawi or Rayner acted dishonestly (or me, for that matter). No jury would have convicted either, and no responsible tax authority or prosecution authority would have brought a prosecution.

Photo by Maxim Babichev on Unsplash

Footnotes

I’m probably supposed to say this is not legal advice, but I’m a lawyer, and this is my advice. ↩︎

This link goes to a page on the former website of accounting firm Aston Shaw. When that link was included, we had no idea who they were. We subsequently found they were part of a corporate group engineering what appears to be large-scale tax fraud, and 11 directors/employees have been arrested. ↩︎

Where exactly you draw the boundary between employed and self-employed is a fascinating and difficult question which I am absolutely not going to get into here. Similarly, I’m not even touching IR35. ↩︎

I go into the loan schemes in more detail here. I’m aware lots of people say they were hoodwinked into the schemes and didn’t realise what they were. But one thing is clear and inarguable: they were tax avoidance ↩︎

In principle tax treaty claims could be made, but that’s often commercially undesirable due to the hassle and potential cashflow cost whilst treaty relief is pending. It also potentially makes the bonds hard to sell/illiquid. ↩︎

Unless the diverted profits tax applies. That’s an anti-avoidance rule that, like many anti-avoidance rules, doesn’t require HMRC to prove that there was intentional avoidance. ↩︎

This is definitely not legal advice – if you do this without taking independent advice, you are crackers ↩︎

Or at least some people intended it ↩︎

That quote originates with Denis Healey ↩︎

Actually there isn’t a single criminal offence of “tax evasion” in the UK. There is a common law criminal offence of “cheating the Revenue” and numerous statutory offences covering different taxes; but all share the key feature I mention here. ↩︎

The subjective element of the test for dishonesty (see Ghosh (1982)) was removed by Ivey [2017] for civil cases, and that decision was confirmed to apply to criminal cases in Barton [2020]. ↩︎

Jolyon Maugham wrote an excellent summary of the issues here – he also thinks it is a non-issue. ↩︎

![To: jeevacation@gmail com[eevacation@gmail com]

From: Peter Mandelson

Sem: Sun 11/7/2010 2 34 57 PM

Subyect: Fwd Rio apartment

Seat to mys bank manager Gratetul tor helpful thoughts trom my chief lite adviser

Sent from ims iPad

Bevin torwarded messave

From: Peter Mander iS

Date: 7 November 2010 [4 29 12 GMI

Subject: Rio apartment

P| ag awe dpeecussed Pan consdernne a purchase of an apartmentin Rion Ttisain](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Screenshot-2026-01-31-at-21.27.15-640x360.png)

Leave a Reply