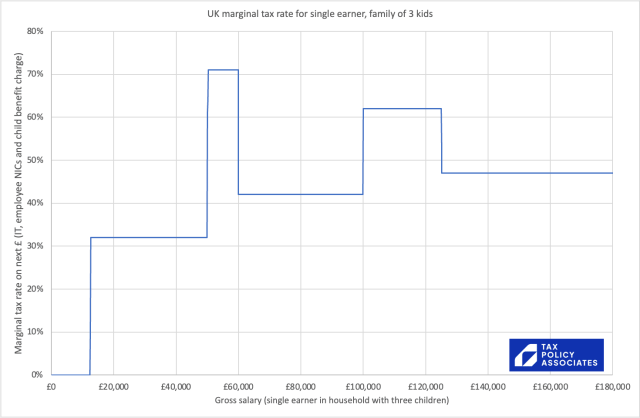

Well-intentioned bodges to the UK income tax system have created anomalously high marginal tax rates for people earning between £50-60k and £100-125k. The marginal rate typically hits 68% but can reach 90%. This is complicated, unfair and a disincentive to work; it could also plausibly be holding back growth. Any government serious about fixing the tax system should start here.

There is an updated article on marginal rates here.

The marginal rate

If you want to know your take-home pay, then it’s your effective rate of tax that’s important – total tax you pay, divided by gross wage (more on that here).

The marginal rate of tax is different and more subtle – it’s the percentage of tax you’ll pay on the next £ you earn. Irrelevant to where you are now, but highly relevant to your future, because it affects your incentive to work more hours/earn more money.1 Economists say everything happens at the margin.

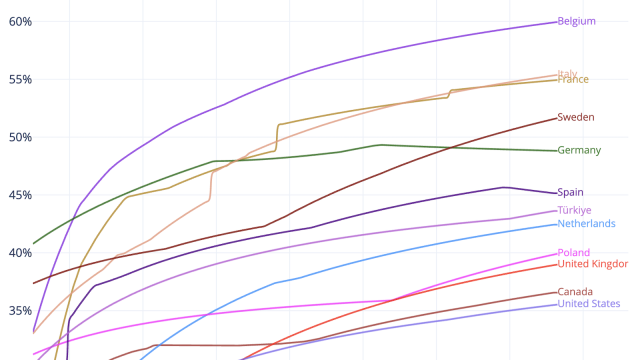

The marginal rate of tax in the UK for high earners in theory caps out at 47% (45% income tax and 2% national insurance) once you get to £150k. I’m not terribly convinced this disincentivises anyone to work. But people earning much less than £150k can have a much higher rate, principally due to two effects:

- Child benefit is £1,133 per year for the first child and £751 for the rest. It starts to be phased out by a special tax – the “high income child benefit charge” – if your salary hits £50k, and you get no child benefit at all once the gross salary of the highest earner in the household hits 60k.

- The personal allowance – the amount we earn before income tax kicks in – starts to be phased out if your salary hits £100k, and is gone completely by £125k.

These phased withdrawals create very high marginal rates.

UPDATE: marginal rates are further increased by student loan repayments. See more below.

The calculations

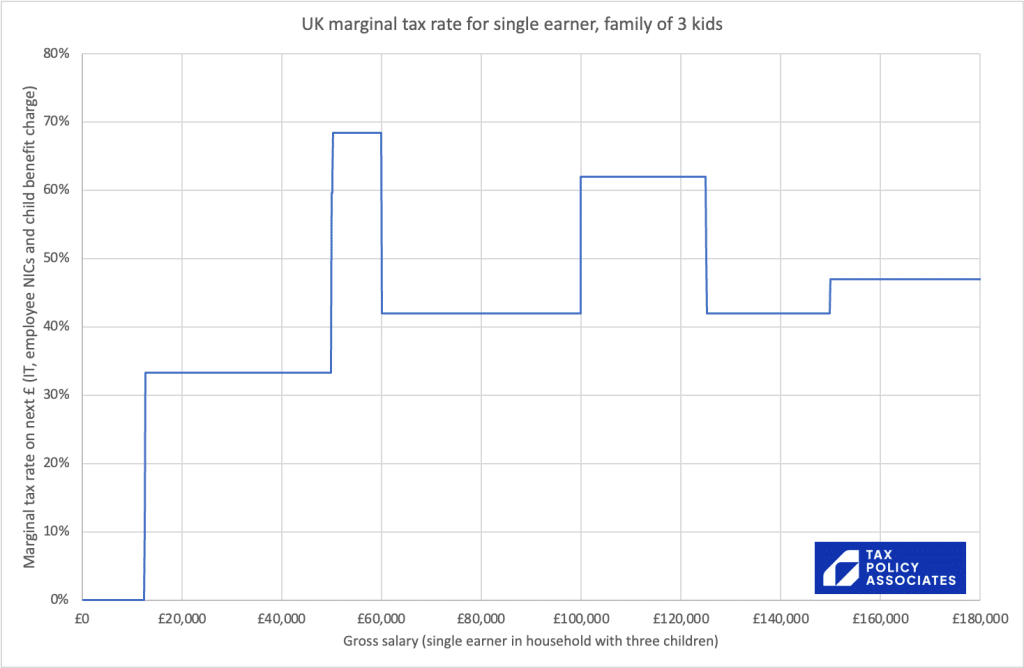

I’ve put together a quick spreadsheet. For a family with three kids, the marginal tax rate for a given salary looks like this:

That bump between £50k and £60k is a 68% marginal tax rate, meaning that, for every additional £1,000 you earn gross, you take home £320.

Looking at it another way: imagine you’re working a reasonably modest 1,500 hours a year and earning £50k gross, so about £38k take-home. That’s £33/hour before tax, £25/hour after tax.

How would you like to work another 200 hours a year for the same pay? Sounds good. But after-tax you’ll be earning £10/hour. You may well not think that’s worth your while. And, if you need childcare, the additional childcare could easily cost you more than the additional pay.

The bump between £100k and £125k is the withdrawal of the personal allowance, and results in a 62% rate between £100k and £125k. Not quite as dramatic as the 68%, but still well over the psychologically important 50% mark – and that rate lasts for a significant £25k.

Let’s go higher

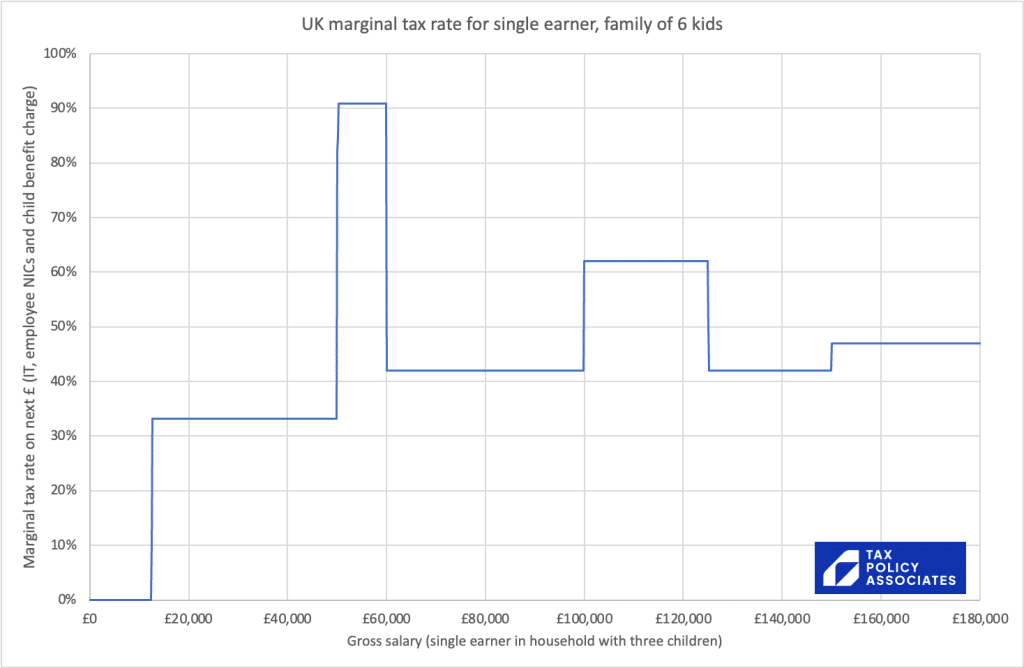

Because it’s linked to child benefits, those high marginal rates just get bigger the more children you have. I have friends with six children. Congratulations, Steve, because you can win a marginal tax rate of 91%.

Why stop there? With eight children you get a top marginal rate of 106% – so if you earn £50k gross, your after-tax pay is £38k. If you earn £60k gross, your after-tax pay is £37k. That’s insane. Hopefully, nobody is actually in that position, but a sensible tax system doesn’t create such results, even in theory.

Update: A clever anonymous coder has made an interactive version of this chart, where you can spawn as many children as you like, and see how high the marginal tax rate goes: here🔒.

Let’s go even higher

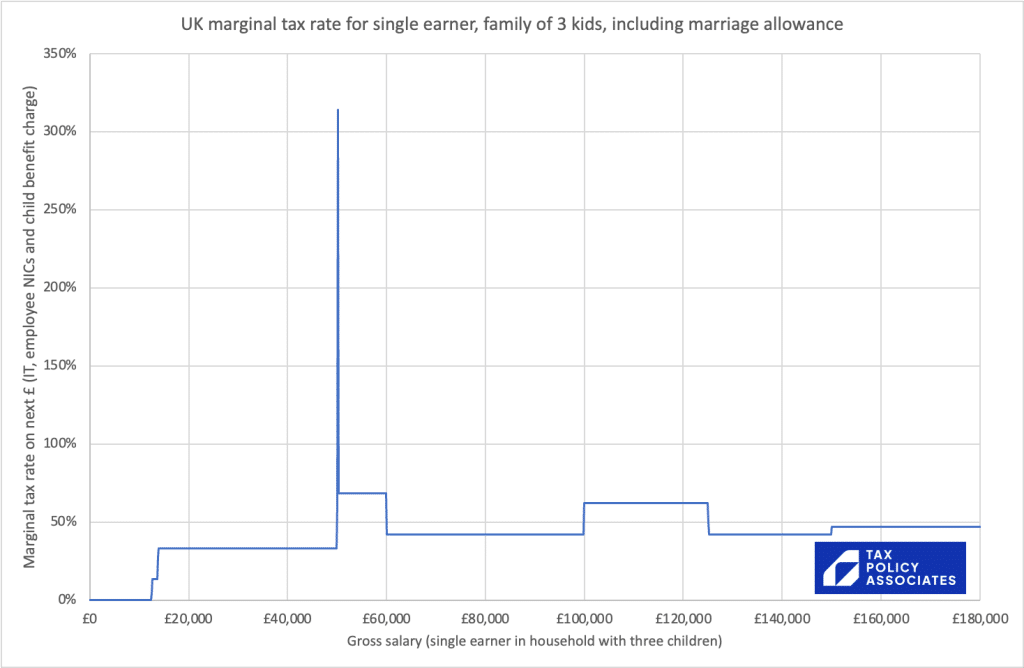

To keep the two charts above readable, I’ve omitted the marriage allowance. This lets a non-working spouse transfer £1,260 of their unused personal allowance to their partner, if they’re earning less than the £50,270 higher rate threshold. So it’s worth £252. Unlike the other allowances, it’s not withdrawn in a phased way – it disappears if the £50,270 threshold is hit. That gives us this beauty:2

Earn £50,200 gross, your take-home is £37,887. Gross £100 more salary, your take-home pay is £214 less. You have to gross £800 more to actually make more money – take-home pay of £7 more, to be precise.

The small size of the marriage allowance means its effect vanishes pretty quickly. But it does combine with the child benefit claw-back to create a zone of extremely high marginal rates which persists for some time:

- Earn £52,200 gross, your take-home is £38,274 – that £2,000 of extra pre-tax income ends up as only £387 of additional money in your pocket.

- Earn £55,200 gross, your take-home is £39,223 – the £5,000 of extra pre-tax income has given you only £1,336 post-tax.

That is not much incentive for someone earning £50,000 to increase their earnings.

What about student loans?

Student loans are really just a complicated hidden graduate tax. For someone starting university before 2012, you pay 9% of your salary over £20,184, until the loan is repaid. Of course, the effect on individuals – even those on the same income – will vary widely, depending on how much loan they borrowed, how long they’ve been earning, and how their salary ramped up over time.

We can model it with some simplifying assumptions. Let’s say everyone on the chart is 30 years old, graduated nine years ago, and their salary ramped up in a straight line from £20k to where it is now. The marginal rates then look like this:3

I’d be cautious about citing these figures, given how dependent they are on the assumptions. However, it’s reasonably clear that graduates suffer from startling marginal rates. Please have a play with the spreadsheet if you’re interested. 4

What about [another stupid feature of the tax system]?

The tax-free childcare scheme creates an insane marginal rate at £100,000.

The basic scheme is that the Government will stump up for 20% of your childcare costs, up to £2,000 per child. You qualify if you and your partner’s earnings hit £7,904, and it’s completely withdrawn if one of your salaries hits £100,000. The result? An infinitely negative marginal tax rate at £7,904 and another brilliantly infinite5positive marginal tax rate at £100,000.6

That £100k spike is absolutely not a joke – someone earning £99,999.99 with three children will lose an immediate £6k if they earn a penny more. They then don’t recover to their previous post-tax earnings until their gross salary hits £119k.

You can see this more clearly if we plot gross vs net income:

There are other similar effects: the thresholds around student maintenance loans for one. But I’m going to stop here for the sake of my sanity…

Why does this matter?

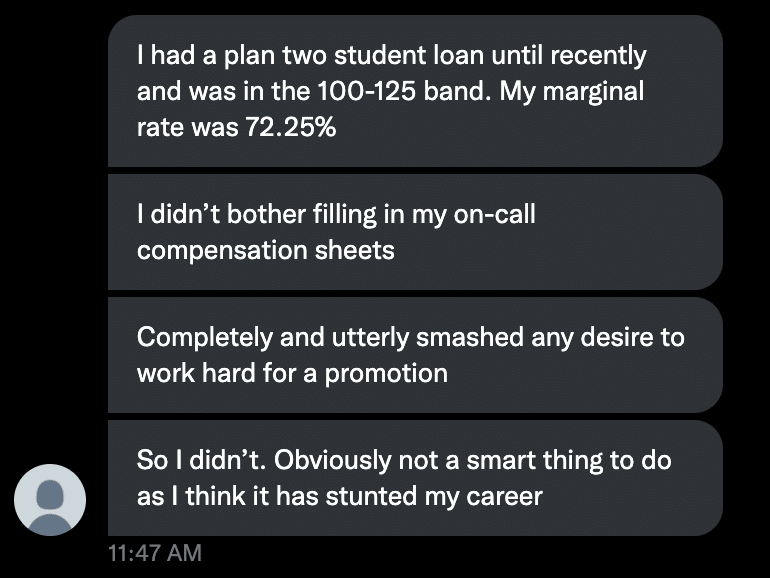

It’s complicated and unfair for people hitting these thresholds. The way the child benefit withdrawal applies means that it catches lots of people out.7 The high marginal rates act as a disincentive to work. Across the whole economy, I’m absolutely not an economist, but it seems plausible these effects act as a brake on growth.

The human side looks like this, one of many similar messages sent to me today:

If we’re looking for ways to fix the tax system, then this should be right at the top of the target list. Regardless of where we sit on the political spectrum.

The solution

One solution is simply to scrap the personal allowance and child benefit tapers (and the marriage allowance to boot).8 Problem is, that would be fairly expensive, on the face of it, costing somewhere around £5bn to repeal both,9 although the widespread awareness of these issues amongst the people affected, and use of salary sacrifice, additional pension contributions, etc, makes me wonder if the actual (dynamic) cost might be materially less.

Realistically the most likely source of funding is playing around with rate thresholds, for example reducing the point at which the additional rate kicks in. There are certainly other alternatives; but the important thing is that we really, really, shouldn’t have a tax system that can have a 68% marginal rate, let alone a 90% marginal rate.

Oh, and the other lesson: please please, politicians and HM Treasury, don’t introduce any more tapers into the tax system. Thank you.

The caveats

All the calculations are in this spreadsheet. The key assumptions/caveats are:

- Income tax/NI as for tax year 2022/23, from November 2022 (so the lower NI rate)

- One earner in a household, who is over 21 and not an apprentice, not a veteran, and under the state pension age

- Ignores benefits aside from child benefit (although benefits are notorious for creating very high marginal rates; to some extent that is unavoidable)

- Doesn’t include the thresholds around student maintenance loans.

- Doesn’t include tapering of pensions annual allowance (starting at £240k)

- Doesn’t include effects of the pension cap – that can create high marginal rates, but as it’s linked to the total size of your pension pot, the rate is very dependent on an individual’s specific position.

Any corrections, additions or comments would be much appreciated. Some kind people have offered to add in universal credit taper. It’s an incredibly important issue, but I’m reluctant to do this given that I have no understanding of the benefits system myself. I’d be delighted if others adapt the spreadsheet to do this.

Many thanks to James Wiseman on Twitter for his original calculation, and credit to William Hague for his article that sparked this train of thought.

Footnotes

For more on this, and some international context, there’s a fascinating paper by the Tax Foundation here ↩︎

Strictly the marginal rate is infinite – it caps at just over 300% in my spreadsheet because the resolution of the calculations is £100. Also I didn’t have a monitor large enough to show an infinite line. ↩︎

Corrected to fix a bad mistake/bug in the spreadsheet ↩︎

Now I’ve added the student loan calculations, I regret doing this in Excel, because it becomes unwieldy. Really needs implementation in proper code. Any volunteers? ↩︎

it’s not infinite – I forgot that you can’t divide money forever. For a couple with three kids, claiming the full £6k, the marginal rate will tend to £6k/1p = 60,000,000% ↩︎

For the chart, the spreadsheet assumes the higher earner in a family pays a maximum of 20% of their gross wage on childcare; if you don’t like that assumption you can change it ↩︎

Fixing student loans is much harder, and tied into a series of policy questions where I don’t feel I have expertise to comment. Really not sure what to do about tax-free childcare. A taper would be better than a £100k hard stop. ↩︎

Back of a personal allowance napkin: 500,000⚠️ taxpayers earn £120k, value of personal allowance is £5k, so approx cost £2.5bn. Back of a child benefit taper envelope: the child benefit taper was expected to bring in £2.5bn of revenue when introduced in 2013. Since then, child benefit has gone up about 10%, and nominal earnings about 30%. Implying costs of around £2.5bn today. The marriage allowance should be small beer by comparison with either figure. Needless to say, these are hugely approximate estimates; I’d be grateful for anything better anyone can suggest! ↩︎

Leave a Reply to J Cancel reply