OneE made £10 million selling doomed R&D tax schemes – leaving investors with nothing and taxpayers footing the bill. Here’s how they did it, and here’s how we would change the law to end the tax avoidance industry for good.

The scheme involved an attempt to use research and development tax relief to generate tax losses for investors far in excess of their actual investment. It was pure tax avoidance, and so technically hopeless that the promoters didn’t even try to defend its main feature in court. The judgment is LR R&D LLP v HMRC.

The continued existence of these tax avoidance schemes is an example of market failure. Investors get ripped off and (more importantly) the lost tax means that the rest of us end up paying more tax (or having worse services).

The scheme

OneE is a well known tax avoidance promoter. They’ve been doing this for years and made tens of millions of pounds of profit.

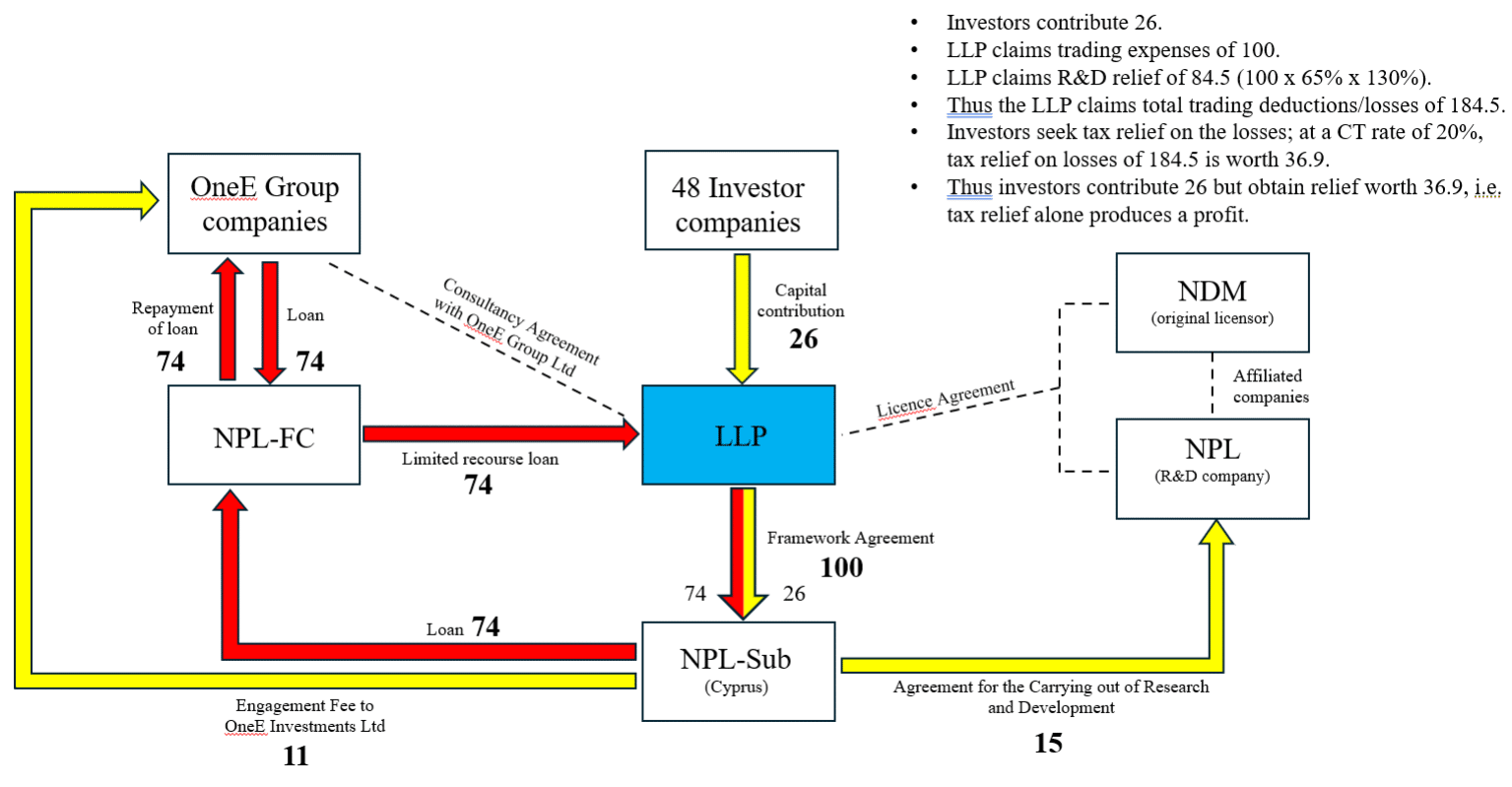

OneE wanted a scheme that let it sell tax relief to clients. The pitch was: invest £26k and, even if you lost everything, you could claim tax losses of £184k. Those losses would be worth £36.9k at the then-corporation tax rate of 20%.

How do you achieve such magic?

- Establish a UK limited liability partnership – an LLP. An LLP behaves a bit like a company, and a bit like a partnership. But the key thing is that it is usually tax “transparent”. If you own an LLP, and the LLP does something, you’re taxed just as if you did that thing.1

- The client puts in £26k.2

- The LLP then borrows £74k from a company called “NPL FC Limited“. It’s a very strange loan, because it’s “limited recourse” – the LLP only has to repay the loan if it makes a return from its investments. No real loan would work like that.

- Where did NPL FC get that £74k? It borrowed it from OneE, the tax avoidance shop.

- The LLP now had £100k from the clients and the loan. It uses all of this to enter into a “framework agreement” with a company called NPL Subcontractor Limited to undertake R&D expenditure. NPL Subcontractor is a Cyprus incorporated company owned by OneE.

- Behind the scenes, NPL Subcontractor makes a £74k loan to NPL-FC, which repays OneE. So the weird £74k loan never really existed. The money just went in a big circle.

- What about the remaining £26k? £11k is paid in fees to OneE, and £15k is used for actual R&D expenditure.

It’s all set out in this diagram included in the judgment.

Let’s say for the moment that the entire investment failed (spoiler: that’s what happened). The LLP claims it has £100k of losses, and these are available for the client, as it’s a member of the LLP and the LLP is “tax transparent”.3

Usually £100k of losses would be worth £20k (as the relevant rate of corporation tax at the time was 20%). But R&D expenditure had a special tax regime, which magnified the losses to £184.5k – worth £36.9k.

So this is how the magic happens: you can invest £26k and get back £36.9k, thanks to the taxman.

And this reflects many previous failed schemes, which all shared the same basic pattern: claim tax relief through an LLP, and “juice it up” through debt. The debt, as with LR R&D LLP, doesn’t really exist, but supposedly means that investors can claim tax relief in excess of their actual investment. These schemes have all failed.

How it failed

The structure was a disaster for the investors. HMRC opened an enquiry and denied tax relief. OneE appealed this decision to a tax tribunal.

It was obvious that the £74k went around in a circle, and so wasn’t R&D expenditure at all. OneE didn’t even bother defending the point in their appeal. That alone meant the structure failed – without the debt “juicing up” the investment, the numbers don’t add up. The investors would now be investing £26k and (assuming the small actual R&D expenditure didn’t produce a return) generating only £48k of tax losses, worth under £10k.

It’s worth pausing to stress this point. The key element of the structure – the feature that made it attractive to investors – was indefensible in court.

That, however, would be the best case scenario. The LLP wasn’t in the best case scenario. The tax tribunal ruled that no tax relief was available at all, for two reasons:

First, tax relief was only available at all (even on the amount actually used as R&D) if the LLP was “trading” – a technical tax term which broadly means you’re just not sitting on a passive investment but actively pursuing profit. The LLP was just passively sitting on its investment, and wasn’t trading. The LLP gets no tax relief.

Second, even if it had been trading, the payments by the LLP were not made “wholly and exclusively” for the purposes of the trade, because they were so heavily motivated by tax considerations. So there would still be no tax relief.

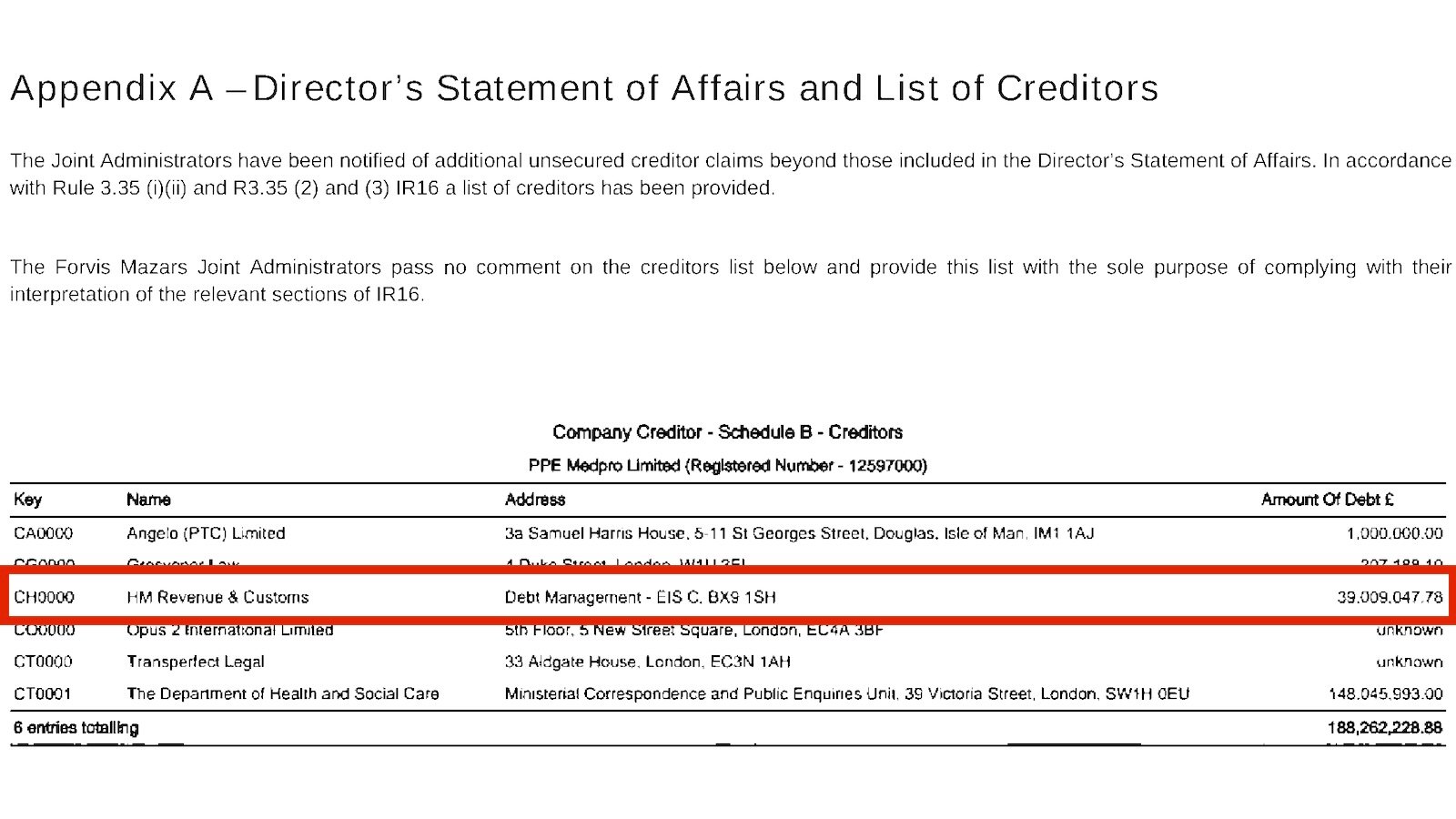

Altogether, the investors in the LLP put in £2m. They lost it all.

There were ten other LLPs – we can track some of them through OneE’s ownership. The investors appear to have been small and medium sized companies. One of them, Pipework Northern (UK) Ltd, liked the scheme so much that it invested in seven LLPs.

A related court judgment suggests OneE’s clients put in £77m in total. All of that was lost.

How it succeeded

The structure was a great success for OneE. It made £906k in fees from this LLP. The figures in the related court judgment suggest OneE’s total fees were at least £10m.4

That wasn’t all kept by OneE. Clients are usually sold this kind of scheme by “introducers” – accountants and independent financial advisers who should know better. One of the reasons they don’t know better is the large introduction fees they receive – here that totalled £2.5m.

So OneE made millions selling an aggressive tax avoidance scheme that never had a chance of succeeding, and it didn’t even try to properly defend in court.

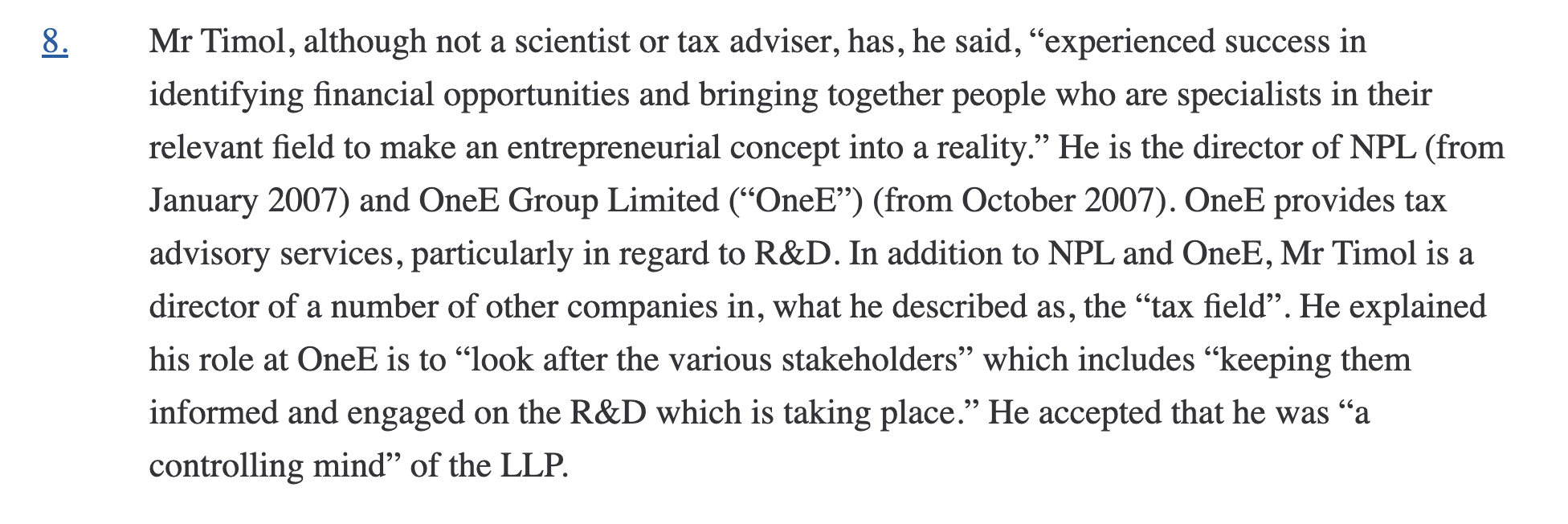

Two of the directors of OneE are Dominic Slattery and Bashir Timol.

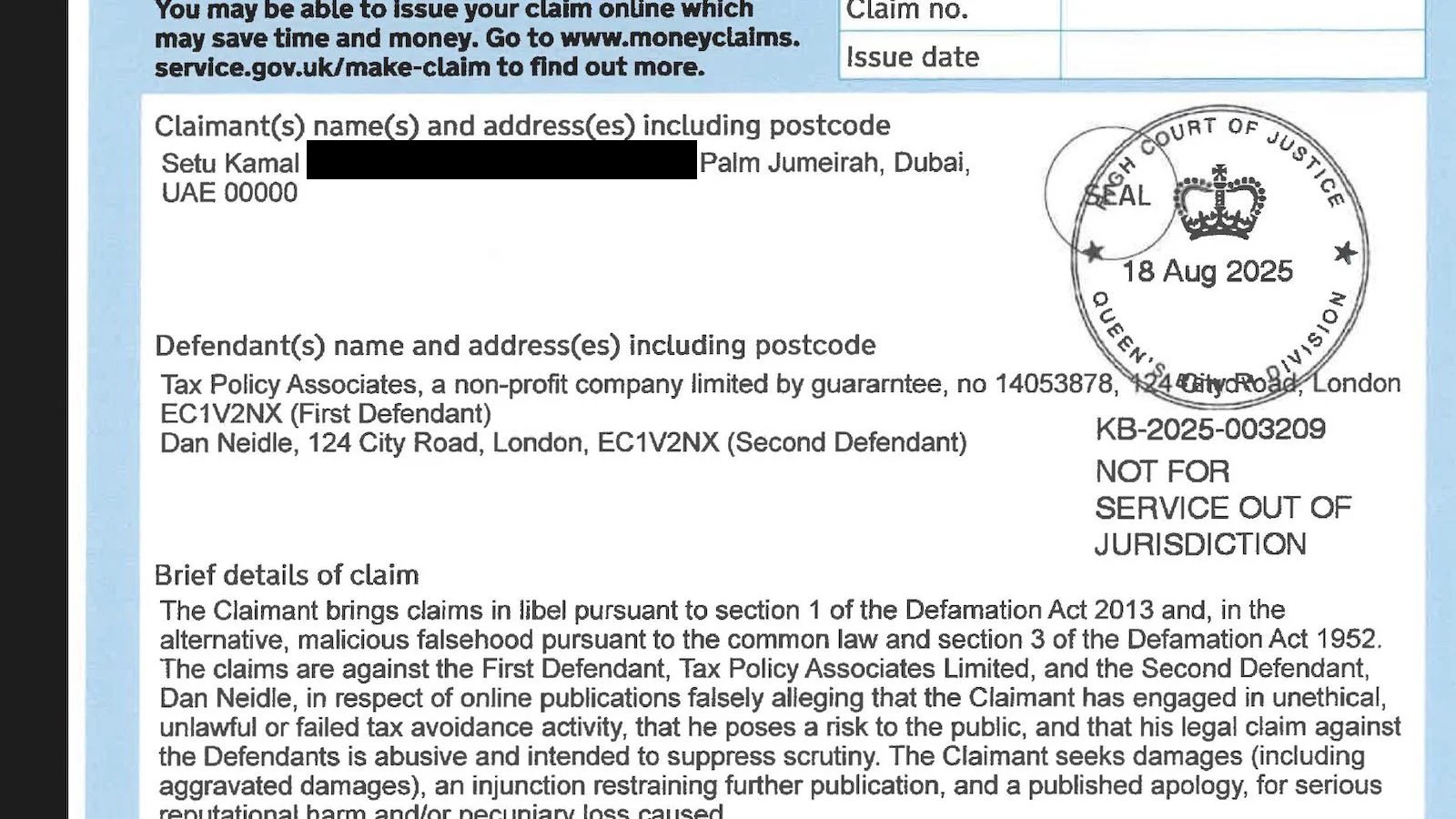

The stolen scheme

The R&D scheme here wasn’t invented by OneE, Slattery or Timol. It was designed by an Irish adviser called Kieran Corrigan. He pitched the scheme to Dominic Slattery and another individual called Timothy Johnson, after they’d signed a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). Mr Timol wasn’t present at that meeting.

OneE later sold the scheme in breach of the NDA.

Corrigan’s company sued OneE and Messrs Slattery, Johnson and Timol personally for breach of confidence. OneE, Slattery and Johnson were found liable for breach of confidence and an “unlawful means conspiracy”.

Mr Timol was not, because he said he wasn’t aware of the NDA. Newly discovered documents called that into question and so Mr Corrigan won on appeal; Mr Timol’s liability will now be the subject of a separate trial.

The judgments in this side-dispute are illuminating, not least because they reveal this as yet another technically hopeless tax avoidance scheme facilitated by tax KC Robert Venables.

The history of dubious R&D claims

OneE has an associated firm that provides R&D tax credit advice – Diagnostax. It appears to be owned by Messrs Timol and Slattery’s wives (via another company called Protech Professional Ltd).

Diagnostax used to operate under the business name of “Radish”. In 2022, The Times caught Radish advising that a pub could claim £28k in tax relief for developing vegan and gluten-free menus.

At the time, Radish’s website included this quote from the pub’s owner:

“I actually didn’t think we’d have a claim, I still can’t believe it – we’re only a small restaurant & hotel! But having spoken to Tim, it’s down to all the hard work that goes into crafting our menus to cater for vegetarians, vegans and those with a gluten-free diet. It’s very difficult to get a menu that suits all tastes and needs, and we can’t have half a dozen different menus as it doesn’t make economic sense. Looking at a menu you don’t see the work that has gone into it, but we do it because we want to please everyone who walks through the door – that is R&D for The Coach House Inn.“

Needless to say, this is pure nonsense, and the defence which Diagnostax provided was risible.

Diagnostax is still making far-fetched claims: their website asserts that 50% of clients can claim R&D tax relief.

They’ve branched out: Diagnostax’s main offering is a “sustainable and profitable tax advice and consultancy service that integrates into your business”. In other words, they’re providing tax advisory services to small accounting firms that lack tax expertise. Given the history of Diagnostax and the people behind it, and their legacy of (at best) inexpert tax planning, we would be highly suspicious of this offering.

A peculiar pharma company

The R&D expenditure was carried out by Nemaura Pharma, which is described in the tribunal judgment as a private pharmaceutical company.

There are several oddities around Nemaura Pharma and its associated entities.

The delisted Nasdaq company

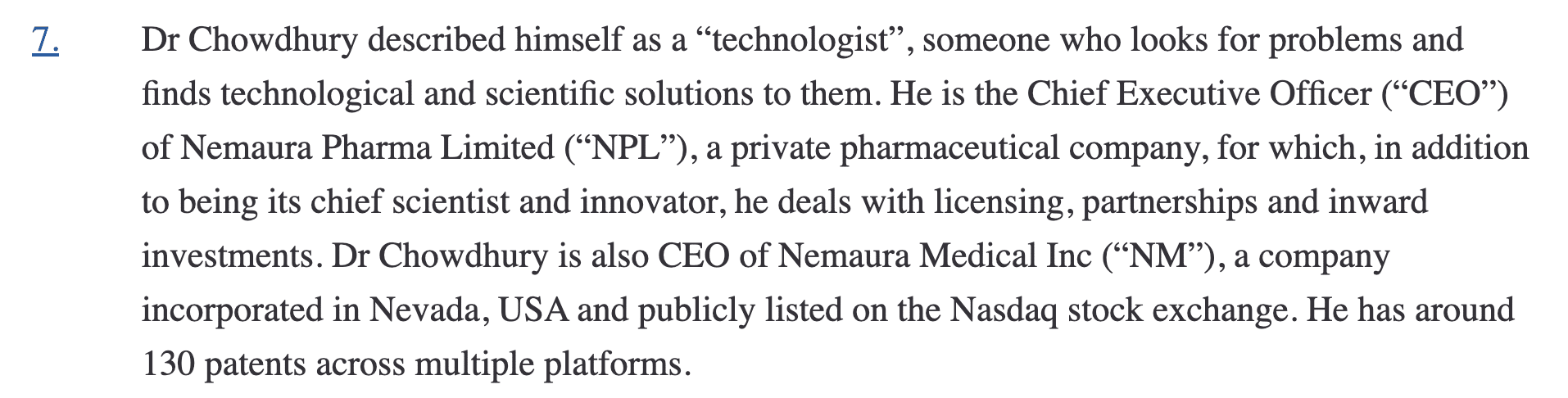

Here’s how the business was described in the tribunal judgment:

Nemaura Medical Inc was delisted from Nasdaq⚠️ in January 2024 because its shares fell below $1 and it then failed to file an annual report and “terminated” its staff. The tribunal hearing was in November 2024; it’s unfortunate if the tribunal was given the false impression that Nemaura Medical Inc had any substance.

The tax-heavy pharma company

Another oddity: Nemaura Pharma Limited was jointly controlled by Dr Chowdhury and a Mr Bashir Timol, a director of OneE (whose main business is selling tax avoidance structures):

When Nemaura Medical Inc listed on Nasdaq, its six-man executive team consisted of Messrs Chowdhury and Timol, one opthalmic surgeon, one accountant and two chartered tax advisers.

Why would a startup pharma company care so much about tax?5

The unusual accounts

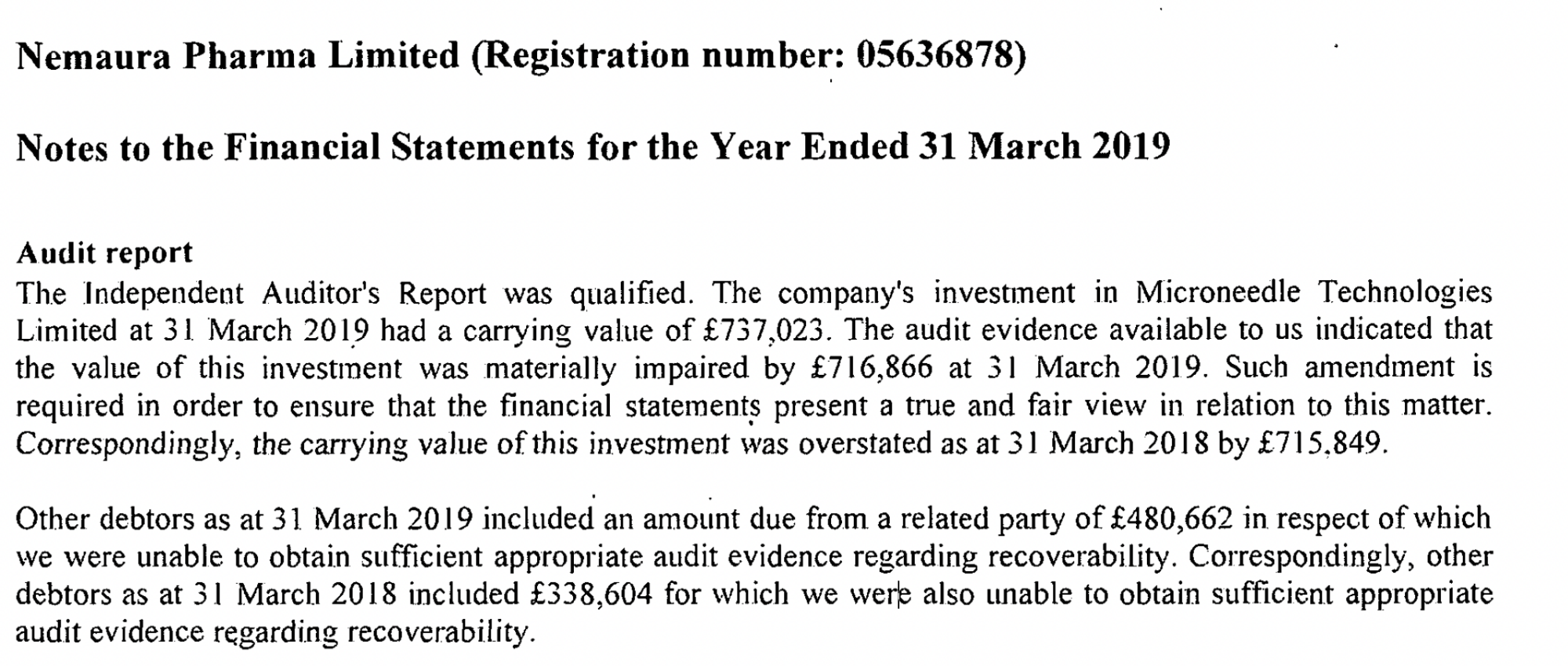

Nemaura Pharma Ltd’s accounts don’t look much like a pharmaceutical company’s accounts. Its accounts for 2015/16, when the largest R&D investment was made by the LLP, showed a company with £4.7m of cash but only £217k of intangible assets. It received significant income over the next few years, but by 2020 it had burnt through it all, without any increase in the value of its intangibles. This is odd for a pharmaceutical company – R&D expenditure is usually capitalised into intangibles.

In 2018, Nemaura Pharma spent £700k acquiring a company called Microneedle Technologies, owned by Messrs Chowdhury and Timol. By 2019 the company was worthless, and the £700k should have been written off. It wasn’t – so the auditors qualified the accounts. That wasn’t the only problem:

There is a web of related companies, often owned directly by Chowdhury and Timol rather than (as one would usually see) part of a corporate group. These companies also have oddities. For example, the LLPs all acquired an IP licence from an “affiliate” of Nemaura called NDM Technologies Ltd. But NDM’s accounts show no sign of this.

So what was going on?

These arrangements don’t make sense to us or the pharmaceutical industry contacts we spoke to. It’s possible that Nemaura was a normal pharma startup with an unusual focus on tax; it’s also possible that something else was going on.

A market failure

It is unusual to find a lawyer or accountant selling a tax scheme. We’d like to think that’s down to strong professional ethics, but there’s another important reason: if the scheme is duff (as it usually will be) then the accountants/lawyer will be sued. The market therefore provides a strong incentive for regulated professionals to provide sensible and prudent advice.

This doesn’t work for tax avoidance schemes like those sold by OneE.

Tax avoidance scheme promoters are in our opinion usually negligent – most tax advisers would say that their schemes have no reasonable prospect of success. However they typically operate through short-lived companies which are dumped by their owners after running the scheme. The main OneE vehicle, OneE Tax Limited, went bust in 2021 owing £70m to HMRC; the directors agreed to pay up £15m. So HMRC lost out twice – the tax lost on the schemes, and the tax lost by OneE’s own failures.

Most of the OneE and associated “pharma” entities have since failed to file Companies House annual returns and are in the process of being struck off.6 The website no longer exists and emails bounce.

So there’s little to be gained by suing a promoter. Nobody involved is regulated or insured, and they’ll just walk away and set up another company..

We said above that tax schemes are often sold by “introducers”: independent financial advisers or accountants who receive a large fee for the introduction. Accountants and IFAs are often regulated and insured, so in principle are attractive litigation targets. The problem is that, if the introducers are careful just to introduce the product (and receive their fee), and not to stand behind it, then they likely won’t have a “duty of care” and can’t be sued in negligence. Here’s an example where an accountant was sued for introducing a client to four doomed schemes, including the R&D scheme.7 There was found to be no duty of care.

And a further problem: tax disputes are very slow burning. It can be years between a client buying one of the schemes and discovering it doesn’t work. By the time it’s completely clear that the scheme failed, the limitation period for bringing a negligence claim will often have expired.

Needless to say, there is no prospect of suing the barrister who advised on the scheme (in this case, it seems, Robert Venables KC). He wasn’t advising the investors – he was advising OneE. We expect the investors were assured that an opinion exists, and they may even have been allowed to see it – but they can’t rely on it as a legal matter.

For these reasons, it is often hard in practice to sue anyone for the failure of these schemes, even though most tax professionals would agree that the schemes never had any realistic prospect of success.

This is a market failure. People are able to sell a duff product with no consequences from either HMRC or their own clients.

We all lose out as a result.

In principle these schemes should fail, with no tax lost. In practice, HMRC won’t always spot the schemes and challenge them, particularly if they’re not properly disclosed. Where HMRC does act, whilst it rarely if ever loses tax avoidance cases on substantive grounds, it fairly often has procedural losses (we’d estimate around 20% of the time). Sometimes that’s due to HMRC mistakes; sometimes that’s just the risk inherent in all litigation. And, where HMRC does challenge a scheme and win, it won’t always be able to recover the lost tax – the taxpayers may simply not have the money to pay it.

Fixing the market failure

One answer is for HMRC to pursue promoters. It does this to some degree, but resource and other constraints means that it hasn’t been able to stop the market in tax avoidance schemes.

An answer we’ve discussed before is criminalising the failure of tax avoidance promoters to disclose their schemes to HMRC, as required by law.

Another answer: ensure barristers are held to the same professional standards as solicitors and accountants, and end the likes of Mr Venables’ involvement in providing highly convenient but technically wrong opinions to people like OneE.

So here’s another solution: let’s fix the market failure. Create a market solution to tax avoidance by making it easier for clients to sue promoters:

- A new right of action should be created where someone is sold an aggressive tax avoidance scheme. How to define “aggressive tax avoidance scheme”? There are typically two signs. One is that the scheme should have been disclosed to HMRC, under the rules requiring disclosure of tax avoidance schemes, but wasn’t. Another is that the scheme falls foul of the general anti-abuse rule (GAAR), because it can’t be reasonably required as a reasonable course of action. Either of these should be enough to trigger a right of action.

- If HMRC then assesses the taxpayer for tax on the basis that the scheme doesn’t work8 then the taxpayer should have a right to recover their fees from the promoter and (where the promoter is a company) its human owners (“participators”). They should also be able to recover HMRC penalties.

- This will be a simple statutory indemnity rather than a new head of negligence.

- Where the taxpayer was introduced to the scheme by an accountant or IFA who received a commission, the taxpayer should have a right to recover that commission from the accountant/IFA. If the commission wasn’t disclosed, the taxpayer should also be able to recover any penalties.

- The limitation period for claims should be three years from the date of the HMRC assessment.

This would dramatically change the game. The prospect of personal liability will scare some promoters out of the business. A rational accountant/IFA should rethink mindlessly referring tax schemes to their clients (particularly if, as is likely, their insurers exclude this new liability from coverage).

It’s a private solution to a public policy problem, and which may just be able to achieve something HMRC has never managed – end mass-marketed tax avoidance schemes.

Many thanks to M for bringing this scheme to our attention, and for his initial analysis. Thanks to V and K for accounting analysis and to T and B for their pharma sector knowledge.

Footnotes

And if you hold 10% of the LLP you’d be taxed 10% of what you’d be taxed if you owned the whole thing. ↩︎

There were of course multiple clients, with £2m invested in the LLP and around ten separate LLPs, but the example will be easier to follow if I assume there was just one £26k client. ↩︎

These schemes no longer work for individuals because of the “sideways loss relief” rules, which stop an investor in LLP using its losses to shelter the investor’s other profits. However the rules (mostly) don’t apply to companies. ↩︎

We say “at least” because both the Corrigan and the LR R&D LLP judgment show 40% of the investments going in fees. The Corrigan judgment says total investments were £77m; and 40% of £77m is of course rather more than £10m. It’s not clear how these numbers reconcile. ↩︎

It’s good general advice for startups of all kinds to ignore tax and indeed most legal considerations until the business matures. Lawyers and advisers will just burn through cash and slow things down, and most mistakes are fixable. ↩︎

Tax avoidance scheme promoters tend to disregard company law. ↩︎

At the time of the judgment it was claimed HMRC hadn’t yet challenged the R&D scheme, so judgment was given on the basis of three failed schemes; that now looks incorrect. ↩︎

i.e. issues a “closure notice” ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Graham Webber Cancel reply