New data suggests that one third of the farm estates affected by the Budget changes aren’t owned by farmers – they’re held by investors for tax planning purposes. This suggests the Budget proposal doesn’t go far enough to stop avoidance, but goes too far in how it applies to actual farms.

There’s a better approach which can achieve the Government’s aim to stopping avoidance whilst also protecting family farms.

We’ve calculated, on the basis of new data, that, if the Budget changes had been in place in 2021/22, fewer than 250 actual farm estates would have been charged inheritance tax in that year. That’s a surprisingly small number, and – given the planning that’s likely to be put in place – we wonder quite how much tax the Budget measure will raise.

At the same time, there’s a surprisingly large number of farm estates which are being held not by actual farmers, but for IHT planning purposes. In 2021/22 there were over 125 £1.5m+ estates in this category. Post-Budget, these would pay some IHT (but much less than a “normal” person). And there’s another 300+ smaller estates using farmland for IHT planning purposes – these would mostly escape the Budget changes, and remain IHT-free.

The Budget therefore risks missing the target:

- Overall, the revenue prospects don’t look very good, and the OBR’s forecast of 40% of revenues lost to tax planning looks optimistic.1

- Some individual farmers won’t be able to plan, and will pay too much.

- People who aren’t farmers will keep using farmland as an IHT planning vehicle, comparatively unaffected by the Budget.

We can fix all these problems at once. Protect real farmers with a complete exemption from inheritance tax (subject to a very large cap, say £20m). At the same time, counter avoidance by clawing-back the exemption if a farmer’s heirs sell the farm. This could achieve the Government’s aims in a way that’s both fairer and more effective – and plausibly raise about the same amount of revenue.

The figures and charts in this article can be found in this spreadsheet.

Inheritance tax – the background

As of today, if someone dies then their estate is subject to inheritance tax (IHT) at 40% on all their assets over the £325k “nil rate band” (NRB). A married couple automatically share their nil rate bands, so only marital assets over £650k are taxed.

The “estate” here has a different meaning from the way the word is often used, e.g. “landed estate”. The “estate” is the legal fiction that springs up when someone dies – the executors manage the estate, and inheritance tax is charged on (usually) the estate.

The Cameron government introduced an unnecessarily complicated additional “residence nil rate band” (RNRB) where the main residence is passed to children. This is £175k per person, and again automatically shared between married couples. So for most married couples, only marital assets over £1m are taxed. The RNRB starts to be withdrawn (“tapers”) for assets over £2m (with planning, a married couple can keep the RNRB with join assets of over £2m2).

It’s different if you’re a farmer. Agricultural property relief (APR) completely exempts the agricultural value of your farmland, farm buildings and (usually) farmhouse (which HMRC tends to accept about 70% is agricultural). Business relief (BPR3) completely exempts machinery and (often) any development value of the land above its agricultural value.

Another important rule: transfers to spouses are usually completely exempt from inheritance tax.

A brief detour for advice for anyone concerned about the impact of inheritance tax on their children if they unexpectedly die young (because marital assets are over £1m or they’re single and assets are over £500k). If you’re relatively young then the answer isn’t elaborate tax planning, it’s making sure you have enough life insurance to cover the tax. That’s very inexpensive if, for example, you’re a banker in your 40s. It gets more expensive if you’re older, less well, or have a relatively dangerous job (which sometimes includes farming).

What changed in the Budget?

BPR and APR were given a combined cap of £1m per person.

Under the cap, the reliefs continue to provide a complete exemption. Beyond that, the reliefs provide only a 50% reduction in the rate, rather than a complete exemption. In other words, any estate past the cap is subject to inheritance tax at 20% instead of the usual 40%.

The changes to BPR have a much wider impact on privately held businesses; but in this article I’ll be talking only about agriculture.

How many people will be affected by the change to APR and BPR?

Let’s park “affected” for now (but return to it later) and ask the easier question: at what level of assets will IHT apply to a farmer?

- For a single farmer who has no material assets other than his or her farm and farmhouse, and plans to leave everything to their kids, the new APR/BPR cap plus the nil rate band plus the residence nil rate band comes to £2m.4. Given that most small/medium farmers live in the farmhouse (usually/mostly covered by APR) and typically don’t have significant other assets, it is the £2m figure which should be used, not the £1m figure for the APR cap.

- For a couple, with some reasonably simple planning, the first £4m will be exempt. But that planning won’t always be possible. The couple may want to keep their finances separate, or there may be complications with third parties (like lenders) who don’t agree to the land and business becoming jointly owned.

So the answer is: usually somewhere between £2m and £4m, depending on circumstances.

The next question is: how many farm estates have this level of assets?

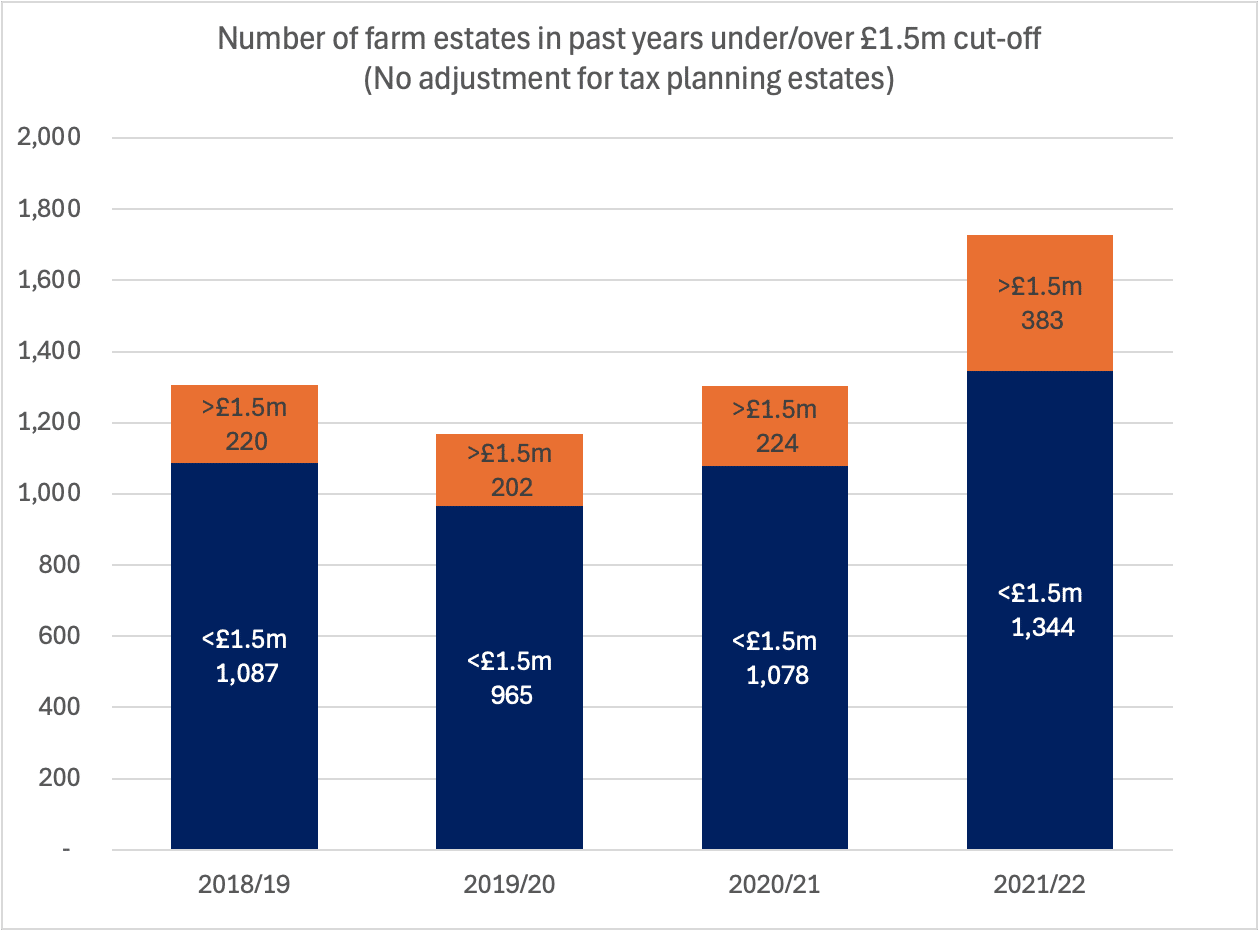

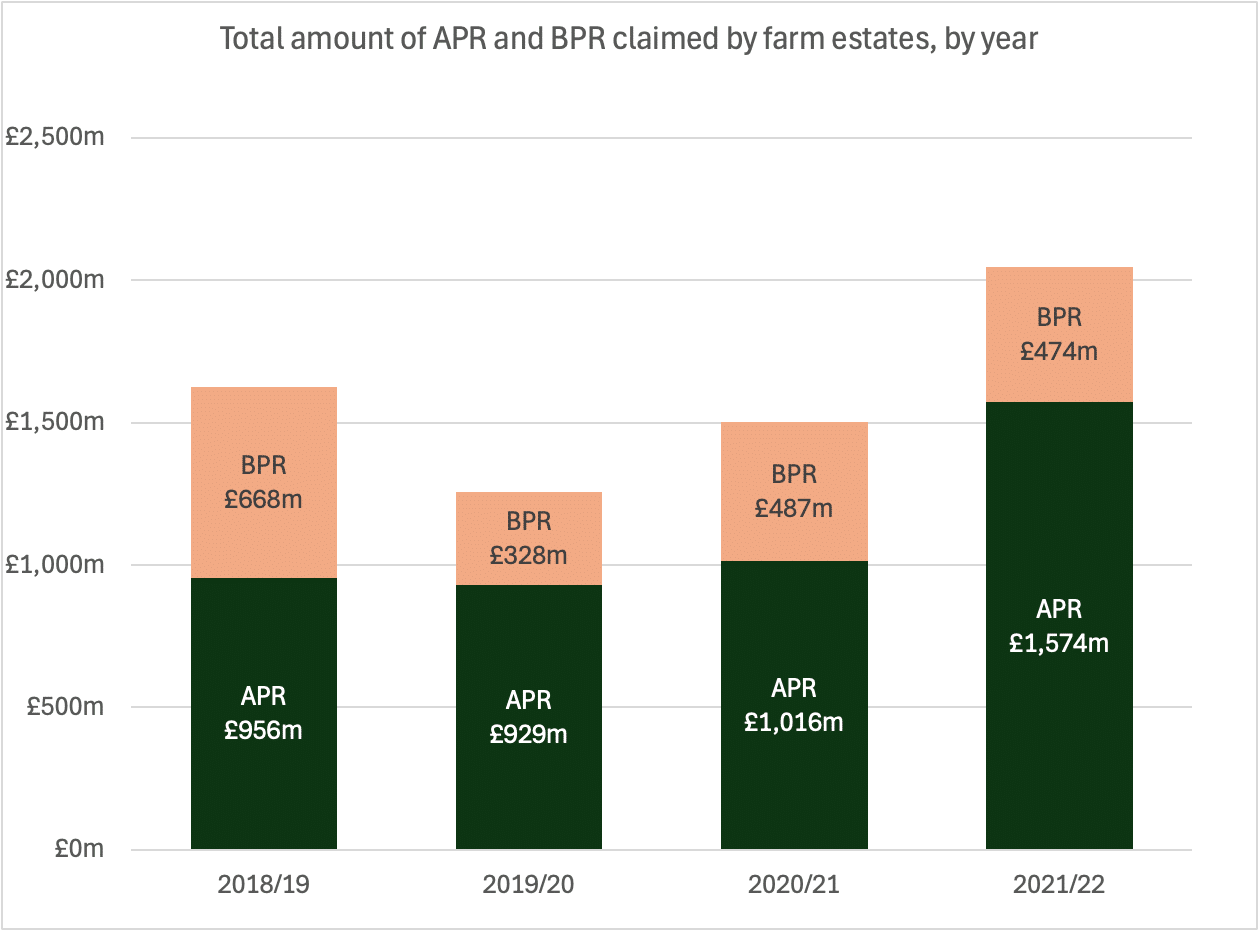

Previously we only had APR data for farms, but now we have both APR and BPR data for years from 2018/19 to 2021/22.5 That gives us a “static” estimate of what the impact would have been, had the Budget changes been in place in that year. The data breaks estate value at £1.5m rather than £2m but, by happy accident, that difference broadly equates to asset price inflation since 2021/22. So the number of estates at £1.5m in 2021/22 should be broadly equal to the number of estates hitting the taxable £2m point in 2025/26.

Some data was published with the original Government announcement. Further more detailed data was published in a letter sent by Rachel Reeves to the Chair of the Treasury Select Committee this week.6

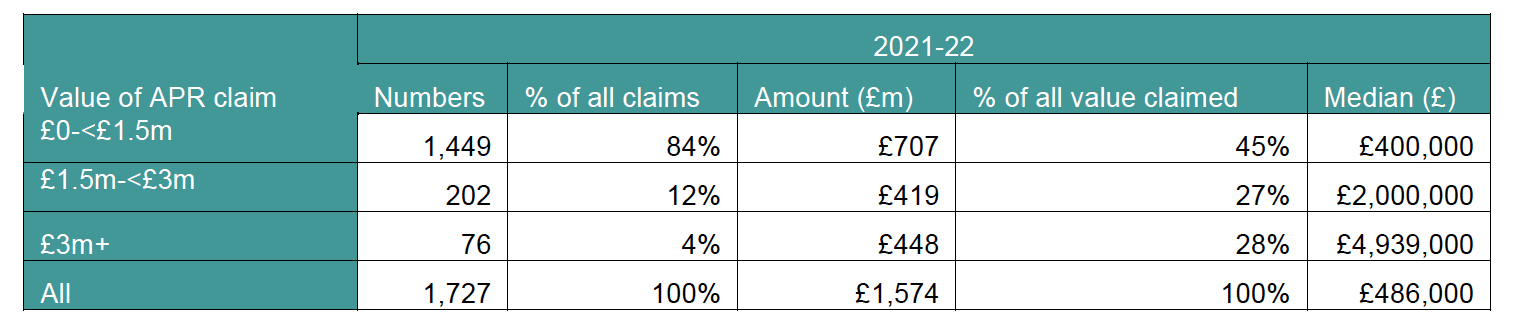

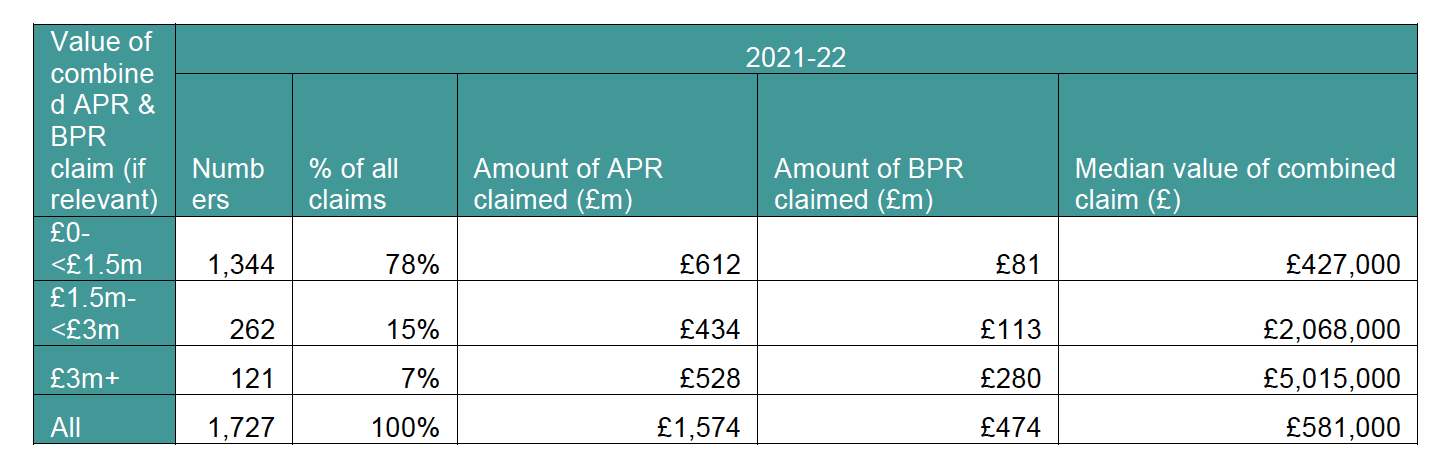

Here are the two key tables for 2021-22. I’ll focus on that year for now (but will return later to the question of whether other years are different).

This table shows estates claiming agricultural property relief (APR):

And this one shows estates claiming APR plus business property relief (BPR).

First point: it’s sensible not to pay too much attention to the large number of small estates. Some will be small farms. Some will be hobby farms. Some will be small fields held as an investment and rented out to a local farmer. Some will be parts of large estates (for example most of a large farm owned by parents but with a significant but <£1.5m portion owned by adult children). I’m particularly interested in the number of large estates.

Second point: on the face of it, a lot of BPR is being claimed – 17% of the total.7

One of the reasons for this is stated in the letter:

“AIM shares” are shares listed on the “alternative investment market” – the junior sibling to the FTSE, for small and medium-sized companies. AIM shares are often used for tax planning because (until the Budget) if you acquired AIM shares8, your holding would qualify for BPR after two years and become entirely exempt from IHT. Most normal investors, even sophisticated ones, don’t hold AIM shares, as the historic returns have not been very good.9

Farmers are very unlikely to hold AIM shares. They’re high risk, historically offer poor returns, and most farmers would invest in their own farms instead. The IHT benefit of AIM shares isn’t a planning strategy that’s very sensible for farmers. None of the advisers I’ve spoken to who work in this area have ever seen a farmer who holds AIM shares.

So we can safely assume that this quarter of all farm APR/BPR claims isn’t from farmers who happen to hold AIM shares. It’s from investors – people looking to shelter their assets from inheritance tax who have bought AIM shares as part of their portfolio, and farmland as another part. The AIM shares are a “signal” that what’s going on here is IHT planning.10

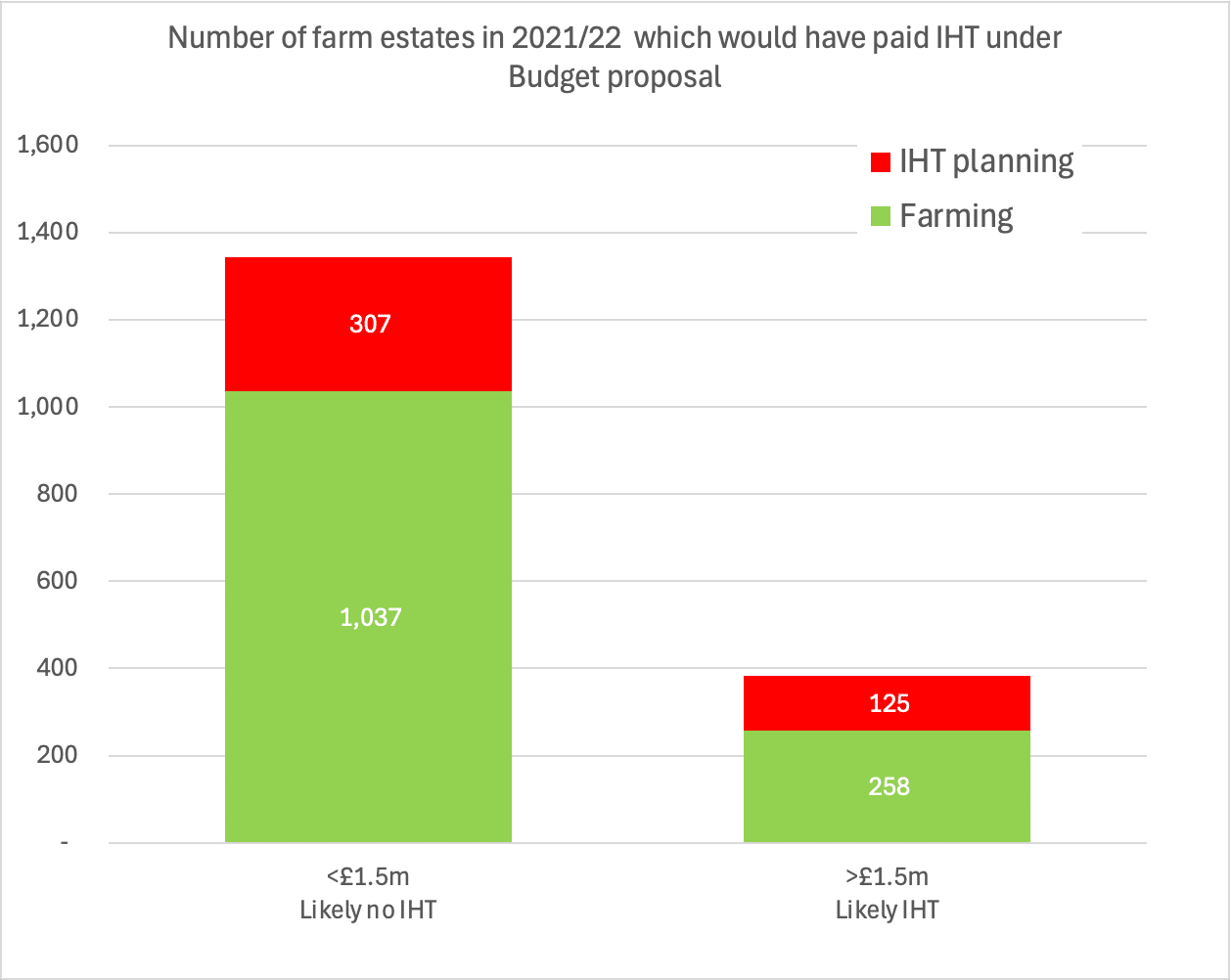

How many of these tax-driven AIM/farming holdings are small, and how many are large? We can calculate this from the information in the Rachel Reeves letter – and the answer is surprising. About 30% of the AIM/farming holdings are over £1.5m.11 The other way to look at this is that, whilst the figures show 383 farming estates over £1.5m, we can be reasonably confident that about a third of these (32%) are just people engaging in tax planning, not actual farmers.

This will be an undercount of estates holding farmland as an IHT strategy, because the calculation only counts those IHT planning farm estates which revealed themselves by also containing AIM shares. There will be many that don’t.

So the true percentage of £1.5m+ agricultural estates which are held for IHT planning purposes will be more than one third.

So here’s the answer to the question of how many farming estates would have been subject to IHT had the Budget rules been in place in 2021/22. Depending on how many are held by single farmers vs couples, how many couples employ tax planning, and myriad other factors: fewer than 250 “real” farming estates.

IHT would also be charged (at 20%) on 125 estates of over £1.5m owning farmland as part of an IHT strategy. And there would be another 300 estates of under £1.5m owning farmland for IHT purposes, most of whom would (post-Budget) still escape IHT altogether.

Or in chart form:

What about other years?

It’s often a bad idea to look at one year in isolation. 2021/22 could have been unusual. Perhaps for a good reason – e.g. fewer deaths post-Covid.12 Or perhaps just statistical fluke – when the numbers are this lowish, they can be dominated by one-off effects (e.g. the absence or presence of a small number of very wealthy estates can push the statistics meaningfully in one direction or another).

The data shows that 2021/22 didn’t have an unusually low level of farming IHT relief – it was a record high:

That was driven by a 50% increase in the number of APR claims. There was no such dramatic effect for BPR:13

This level of change is very surprising, and I don’t know what the explanation is.14

We don’t have AIM figures for other years, but it would be surprising to see a very different result.

Why do these figures show so few farm estates worth over £1.5m?

The NFU says that 75% of commercial family farms are above the £1m threshold. How can that be the case, if only a few hundred estates would be subject to IHT every year?

Because the number of estates is not the number of farms, and IHT applies to estates, not farms.

- Farmers, particularly those owning large farms, often give some or all of their property to their adult children when they retire. This can be for succession or tax planning reasons (because often APR/BPR does not provide a complete exemption). Tax rules make this relatively easy, and there normally isn’t a capital gains tax charge. So relatively few large farms end up in probate – the number of farm estates is always going to be less than the number of farms. (Those owning smaller/less profitable farms often financially aren’t able to do this.)

- Many farms are held by multiple people, e.g. a married couple and one or more of their children, owning the business together either in partnership or through a company. The NFU says, I’m sure correctly, that multiple ownership is unusual for small farms, but they concede that “multiple ownership might be more common in larger farms”. The farmers and advisers we spoke to believe it is indeed more common. So some (and perhaps many) of the <£1.5m estates will actually be interests in much larger farms.

There is no conflict in the data, and there conceptually shouldn’t be. If we want to know what the impact of the Budget changes would have been in 2021/22, the only data that’s relevant is the APR and BPR data for 2021/22.

The NFU are measuring the wrong thing.

Does this mean fewer than 300 farms will be affected?

That conclusion would be wrong.

The number of farms affected by the change will be larger than the number of estates subject to IHT each year. All farmers at, or approaching, the threshold will need to put planning in place. Those well over the threshold, or for whom planning isn’t appropriate, will worry about the consequences.

This can be for many reasons that are not a result of a failure to act on good advice, e.g. risk of divorce, restrictions on transfers due to banking requirements, financial or personal vulnerability of heirs, etc.

How many are in this category? That depends on how we define a generation, how long people will think the new IHT rules will remain in place, how worried we think people will be about events 25 years in the future, and what assumptions they’ll make about IHT rules in place at that time.15 It would be wrong to be more precise than “a few thousand” likely being affected. But that also means a larger number, probably low tens of thousands, are worrying about being affected. Farming tax advisers tell me they’re seeing an unprecedented level of demand.

What other adjustments do we need to make to the figures?

There are at least two factors which (of themselves) would make the number of farms affected in 2025/26 larger than the 2021/22 figures suggest:

- The value of farmland in 2025/26 will be higher than the value in 2021/22. There has been considerable asset-price inflation since 2021/22. Various sources say farmland has gone up somewhere between 4% and 8%⚠️ each year. That suggests, by the time the new rules come in, valuations will be between 17% and 36% higher than those in the 2021/22 data. So the number of estates we found to be at the £1.5m point in 2021/22 will in fact be closer to £2m in 2025/26. By happy accident, £2m is the actual figure where IHT is likely to start applying… so asset inflation doesn’t end up changing our conclusions.

- The figures in the tables above include farms held by companies, but don’t include farms held on trust (or farms owned by companies owned by trusts). The rules for trusts are different: broadly speaking trusts aren’t subject to IHT when an individual dies; instead, there’s a 6% charge every ten years. APR and BPR used to provide a complete exemption from that charge. Trust assets over £1m will now be subject to a 3% charge every ten years. Some of the UK’s largest landowners hold property through trusts, as well as sophisticated individuals⚠️ and some relatively small farms too (typically for current or historic succession planning reasons).

Set against this, there are three factors pushing in the other direction:

- The high number of farm purchases driven by IHT considerations means we can expect the IHT changes to reduce the value of farmland, particularly farmland over £1m. Exactly how much is hard to say, other than there will be an effect which is greater than zero, and less than 40%.16

- I took out estates including AIM shares from the figures above, because we can be reasonably confident they were engaged in tax planning rather than farming. But there will be additional estates in the figures where people acquired farmland for tax planning reasons but didn’t acquire AIM shares (e.g. because they viewed AIM shares as too risky). We don’t know how many such estates there are – perhaps dozens, perhaps over a hundred.

- Taxpayers will, as is always the case, change their behaviour to minimise the tax. The OBR estimates this will reduce revenue by about a third.17 There will be more use of the spouse exemption, and more gifting. Possibly also more use of trusts.

Why do the numbers matter?

Two reasons:

- The small number of actual farming estates affected tells us that the potential revenues are quite fragile. Any tax which collects relatively large amounts from a small number of people is likely to be subject to very significant planning. The advisers I speak to think that the OBR’s estimate of a one-third revenue loss from planning is optimistic.

- The surprisingly large number of IHT planning estates affected tells us that the proposal is failing to collect as much revenue as it should from the people it is actually aimed at. And, as noted above, the figures on this are an under-count because there will be IHT planning farm estates which don’t reveal themselves by also containing AIM shares.

Which raises the question as to whether the right approach is being taken here.

What would a fair policy look like?

Questions of “fairness” are very subjective, and we need to start with some principles⚠️.

First, if we accept the basic Budget approach, it should be made to work more fairly

Here there are some principles I think most people would agree with:

- Tax systems should treat people in a similar situation similarly. It’s unjust if two people in identical positions face radically different IHT results, depending on whether they obtained advice. All of inheritance tax used to work this way, with one spouse’s nil rate band “lost” unless simple planning was put in place. That changed in 2016, with the NRB now transferring automatically. It’s unclear why the APR/BPR cap doesn’t work the same way.

- It’s also unjust to make people spend time and money on tax planning to overcome shortcomings in legislation.

- If we are judging the fairness of the Budget based on a £1m cap as it applies today, then that cap should not be permitted to be eroded by asset price inflation. Recent experience has been that IHT thresholds don’t rise with inflation – the nil rate band hasn’t changed in fifteen years. So many farmers will rationally fear that asset inflation will bring their smaller farms within scope.

These are fairly easy to overcome:

- The £1m cap should automatically transfer between spouses, and (as was done for the residence nil rate band) retrospectively transfer for farmers whose spouse died in the last few years – becoming £2m in either case.

- The legislation should automatically raise the £1m cap in line with inflation (or some other fair measure of asset values).

- As the IFS suggests, the usual seven year gift rule should be relaxed for farmers. They (entirely reasonably) didn’t expect they’d ever have to plan for inheritance tax, and so some older farmers haven’t passed the farm to their children in the way they might have done if they’d thought about inheritance tax planning. Many will now be too late – and the rules could be relaxed to prevent what would otherwise be a significant unfairness.

Would these changes be sufficient?

Second, we should do a better job of targeting IHT planning/avoidance

Here some people will take the view that IHT itself is immoral, and all IHT planning is acceptable; even laudable. That’s not my view.

I would say:

- It’s wrong that one person can inherit a £3m house from their parents and sell it, with £800k inheritance tax, and another inherit £3m of farmland and sell it, with no inheritance tax.

- That’s a particularly unfair outcome if the situation was engineered (i.e. because their parents weren’t farmers, just wealthy people engaging in tax planning).

- And this tax planning has wider adverse consequences, creating artificial demand for farmland, boosting asset prices and hence reducing farmers’ return on capital.

The problem is that the Budget changes don’t stop tax planning very effectively. Acquiring farmland for IHT purposes remains a great strategy if you hold less than £1m (or £2m for a couple). And a pretty good strategy beyond that (20% IHT is better than 40%!).

I would instead refocus the changes to remove the IHT benefit for people who hold farmland for planning purposes. How to do this in practice?

- One approach: a “clawback” of all APR/BPR relief for a farm if those inheriting farmland sell it within a certain time. In other words, upon a sale, all the IHT that was previously exempt suddenly reappears and becomes charged. This isn’t a new concept. The UK already has similar clawback rules for other taxes. Ireland has a similar rule for its farming inheritance tax relief. The clawback period would have to be reasonably long (years not months) and should “taper” down gently to avoid a cliff-edge.18

- Or there’s a more radical solution which is being suggested by some – ending all IHT relief for owners of farmland who don’t occupy the land. That would certainly stop the use of farmland for tax planning. It would, however, have much wider effects. About half of all farmland is tenanted, and tenant farmers are concerned that their tenancies could be lost if the landowners sold part of their land to fund an IHT bill. I don’t know if that’s correct, but the point would need to be looked at very carefully. And then there is an additional complication – many farmers who own and operate their own farm will hold the land in a separate company. It would not always be easy for legislation to distinguish this case from a third party investor.

There may be other potential solutions. However the clawback route seems to me the most practicable.

Third, do we actually want to impose IHT on family farms?

Farmers owning farms which they believe are worth c£5m have told me their profit is currently so modest (under 1%)19 that the £400k inheritance tax bill they’d face under the proposed rules is unaffordable and couldn’t be paid up-front or financed – they would have to sell up.

How do we respond to this?

One approach is to say that a family farm yielding a 1% return20 isn’t economically viable when far better and easier returns on capital could be obtained elsewhere. Someone inheriting a £5m farm post-Budget could sell it, pay the £500k inheritance tax, buy a nice £1m house and stick the rest of the money in an index tracker fund – they and their descendants could then live happily off the c£150k income for essentially ever. Presumably that’s not a result farmers want, or they’d have done it already. Is it a result we as a society want? Are the economic effects positive (larger, more efficient, farms) or negative (lots of smaller <£1.5m less efficient farms)? What about the social consequences? How would food security be affected?

But if we’re happy with this outcome then we’re done, and all that’s necessary is to to make the new rules a bit fairer in terms of automatic transfer and indexing the cap, and being less facilitative of avoidance.

If we’re not, we need to find a better solution.

A better solution?

One response would be to adjust the way the current proposal works. For example: have a series of different caps and progressive rates.

I’d suggest something simpler: raise the cap dramatically (say to £20m21 In practice this will probably almost all be to trusts, so a 6% charge every ten years.[/mfn]) so that only the largest and most sophisticated farm businesses become subject to IHT (which they can fund through finance or selling part of the business). For everyone else, keep APR/BPR for farmland exactly as it is today, but – critically – with the “clawback” rule I suggest above. The clawback period would be set long enough to make farm IHT planning unviable for non-farmers:2223

- This would have no impact on a family farm succession planning, if the farmer’s heirs continue to own the farm.

- It would mean inheritance tax at 40% if some or all of the heirs cash out. But why shouldn’t it? If realistically they’re inheriting £5m cash then it’s only fair they’re taxed the same way as anyone else inheriting £5m of cash.

- And it would certainly mean inheritance tax at 40% for someone who buys farmland solely for IHT purposes (given that their children won’t be expecting to hold onto farmland forever, particularly at current yields).

We’d be taxing farmers a lot less, but IHT-exemption-chasing investors a lot more. My back-of-a-napkin calculations suggest that the revenue difference between this and the original Budget proposal is plausibly rather small, and could be positive.

Thanks to the farmers and farm tax/financial advisers who discussed the CenTax proposal with me. All opinions and any errors are my sole responsibility.

Footnotes

See page 58 here. ↩︎

In principle the RNRB could be retained in full with joint assets up to £4m, but in practice change in asset values between deaths make this very unlikely. ↩︎

The relief used to be called “business property relief” and many HMRC/HMT publications still refer to that, and “BPR” is more commonly used than “BR”. ↩︎

I and some others initially said the figure here was £1.5m – the £1m cap plus NRB plus RNRB. But that’s wrong, because the 50% APR/BPR relief applies first. So a £2m estate completely covered by APR/BPR has £1m completely exempt, then £1m relieved at 50% to £500k. That £500k is then covered by the NRB/RNRB. ↩︎

The BPR data makes little difference to the number of estates that would be taxed, because BPR for the smaller farms is very limited (BPR of course applies to all private businesses, of which farms are a relatively small proportion). ↩︎

There is additional historic data in the HMRC “non-structural” tax relief statistics here. But these figures are out of date, and therefore the 2021/22 figures are too low. The enticing 2022/23 and 2023/24 figures in this data are just forecasts, so I wouldn’t read too much into them. ↩︎

This is surprising given that agriculture is a small percentage of overall UK private business, even if we adjust for the fact that farming makes up a larger proportion of UK private business assets than it does of UK private business GDP. I’d welcome thoughts on why the figure here is so high. ↩︎

Or at least the right AIM shares ↩︎

Important point of detail: the BPR exemption applies to all shares listed on exchanges which aren’t “recognised stock exchanges“. So it applies to AIM (but not the FTSE). It also applies to some quite significant foreign exchanges, like the National Stock Exchange of India. ↩︎

The forecast on page 5 of the letter projects the number of APR/BPR estates including AIM shares falling dramatically by 2026/27, presumably because of the restriction being introduced on AIM BPR in the Budget. ↩︎

We can find this using simple maths because we have two pieces of information. First, we know that the number of AIM estates is about 432 (25% of 1727). Then we know that if we take the number of AIM estates out of the figures, the proportion of <£1.5m estates rises slightly to 80%. Let P be proportion of AIM estates under £1.5m. The number of <£1.5m estates if we take out the AIM estates is then: 1344 – 432P. As the proportion of <£1.5m estates is 80%, that tells us that (1344-432P) / (1727 – 432) = 0.80. So P = 71%. ↩︎

Some have suggested there could have been underreporting that year due to Covid-era backlogs. That shouldn’t be the case – the figures are for deaths in 2021/22 not filings in that year. The deadlines for probate, IHT returns and HMRC responses mean that the data for 2021/22 should now be reasonably complete. ↩︎

There was a significant jump in high-value BPR claims in 2018/19, but that was likely just a few very high value estates. ↩︎

It shouldn’t be Covid, because the data is for deaths in the relevant year, not filings in that year (and any increase in death rate would impact the BPR figures as well as the APR figures). ↩︎

This is a problem that bedevils IHT planning. If you’re planning for events 30 years ahead, you have to assume IHT rules will change numerous times. Indeed the concept of complete exemption for farms is only 32 years old. ↩︎

This is something it should be possible to analyse after the event, by comparing the change in market value of farmland above and below the £1m and £2m points. ↩︎

See page 55 here. ↩︎

This approach would certainly bring complications. How long would the “clawback period” be? Too short, and people would just wait before they sold. Too long, and it becomes hard to enforce. And applying to trusts brings a further level of complication. “It’s all very complicated” is the usual response to all tax changes, but complication can’t always be avoided. ↩︎

I say “believe” because I confess I don’t understand how economically it’s possible to have an asset worth so much but yielding so little. APR only applies to the pure agricultural value of property (not development value, hope value etc). BPR can apply to exempt non-agricultural value from IHT, but it’s not always straightforward, and won’t apply at all for the 50% of farms that are tenanted. But this is an aside – farmers clearly believe that there is a massive disparity between asset value and return. ↩︎

Important to note that these “return on capital” figures usually deduct an amount for the farmer’s labour. That’s economically the correct approach, but means in cash terms the farmer is receiving more than 1%. ↩︎

I’m not wedded to any particular figure. The idea is that very large landowners, who realistically can afford the IHT, pay it. It also restores the original purpose of the old estate duty – to prevent vast tracts of land becoming permanently locked into huge estates. Beyond the £20m, IHT should apply in full.21It may also be worth revisiting the current qualification period. Currently this is seven years for passively held farm interests, and two years for active farmers. The two year period may need extending. ↩︎

It’s six years in Ireland – but I’d tentatively suggest we need a longer period to make IHT planning non-viable. There would undoubtedly be calls to make the clawback more flexible, e.g. an exception for a forced sale of the farmhouse of one kind or other. I would take great care before creating such exceptions, as they’d inevitably be exploited for avoidance purposes. Limit exceptions to cases that are hard to exploit, like compulsory purchase (if the purchase monies are used to acquire new farmland). ↩︎

If this proposal was enacted then the obvious step for someone previously using APR to avoid IHT would be to move into an AIM (or other unlisted share) portfolio given that, even post Budget, AIM shares still receive 50% relief. I would give serious consideration to restricting AIM relief further, or abolishing it. If you close one IHT planning strategy, people will move to others – you have to shut them all. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Gwyndaf Cancel reply