Property taxes are probably more in need of reform than any other area of UK tax. We have three taxes on property: stamp duty (SDLT), council tax and business rates. They’re bad taxes: they’re unpopular, inequitable, and they hold back growth.

There is a way to change this, and tax land in a way that encourages housebuilding and economic growth. But that requires smart thinking and brave politics.

This Government was elected on a platform of kickstarting economic growth. It has a large majority, and four or five years until the next election. It’s a rare chance for real pro-growth tax reform. That’s all the more necessary if we are going to see tax rises.

We’ll be presenting a series of tax reform proposals over the coming weeks. This is the sixth – you can see the complete set here.

Abolish stamp duty

Stamp duty land tax (SDLT)1 is a deeply hated tax.

This is well-deserved. Stamp duty reduces transactions. There’s an excellent HMRC paper summarising research on the “elasticity”2 (i.e. responsiveness of transactions to changes in the tax) for residential transactions, and looking at new data for commercial transactions. A 1% change in the effective tax rate results in almost a 12% change in the number of commercial transactions and a 5-20% change in the number of residential transactions (different effects for different price points/markets).

This all creates a distortion in the property market, and often stops businesses and families moving when otherwise would. So stamp duty reduces labour mobility, results in inefficient use of land, and plausibly holds back economic growth.

It also makes people miserable.

And the rates are now so high that the top rates raise very little; HMRC figures suggest that increasing the top rate any further would actually result in less tax revenue.

Stamp duty only exists because, 300 years ago, requiring official documents to be stamped was one of the only ways governments of the time could collect tax. We have much more efficient ways to tax today – but stamp duty remains. Until four years ago HMRC still used a Victorian stamping machine.3

Transaction taxes are generally undesirable from a tax policy perspective. The tax system shouldn’t discourage people from transacting.

We should abolish stamp duty.

The problem with abolishing stamp duty

Abolishing SDLT would result in some additional tax as the pace of transactions picks up, and research in 2019 suggested abolition of SDLT wasn’t too far off from paying for itself. However, at that point SDLT raised £5bn. Subsequently rises in SDLT rates and property values mean that it now raises £12bn each year – an amount that’s hard to ignore. The trouble with many bad taxes is that, as they become more and more significant over time, HM Treasury becomes addicted to them.

Unfortunately there’s an even worse problem than the cost: abolition would inflate property prices.

The link between stamp duty and prices is clear when we look at the impact of the 2021 stamp duty “holidays” on house prices.

The spikes in June and September coincide with the ends of the “holidays”. People rushed to take advantage of the discounted stamp duty, and prices rose accordingly.

Of course the “holidays” were temporary – but the chart suggests that there was a permanent upwards adjustment in house prices (probably due to the “stickiness” of house prices).

Previous stamp duty holidays had less dramatic effects. There’s good evidence that the 2008/9 stamp duty holiday did lead to lower net prices, but 40% of the benefit still went to sellers, not buyers. I’d speculate that the difference is explained by the much lower stamp duty rates at the time.4

A detailed Australian study looked at longer-term changes than the recent UK “holidays” – it found that all the incidence of stamp duty changes fell on sellers (and therefore prices). This is what we’d expect economically in a market that’s constrained by supply of houses.5

These effects mean that stamp duty cuts aimed at first time buyers may end up not actually helping first time buyers. An HMRC working paper found that the 2011 stamp duty relief for first time buyers had no measurable effect on the numbers of first time buyers.

Abolition would just create a windfall for existing property owners. We need something smarter.

Abolish council tax

Stamp duty isn’t our only broken property tax. Council tax is hopeless – working off 1991 valuations, and with a distributional curve that looks upside down.

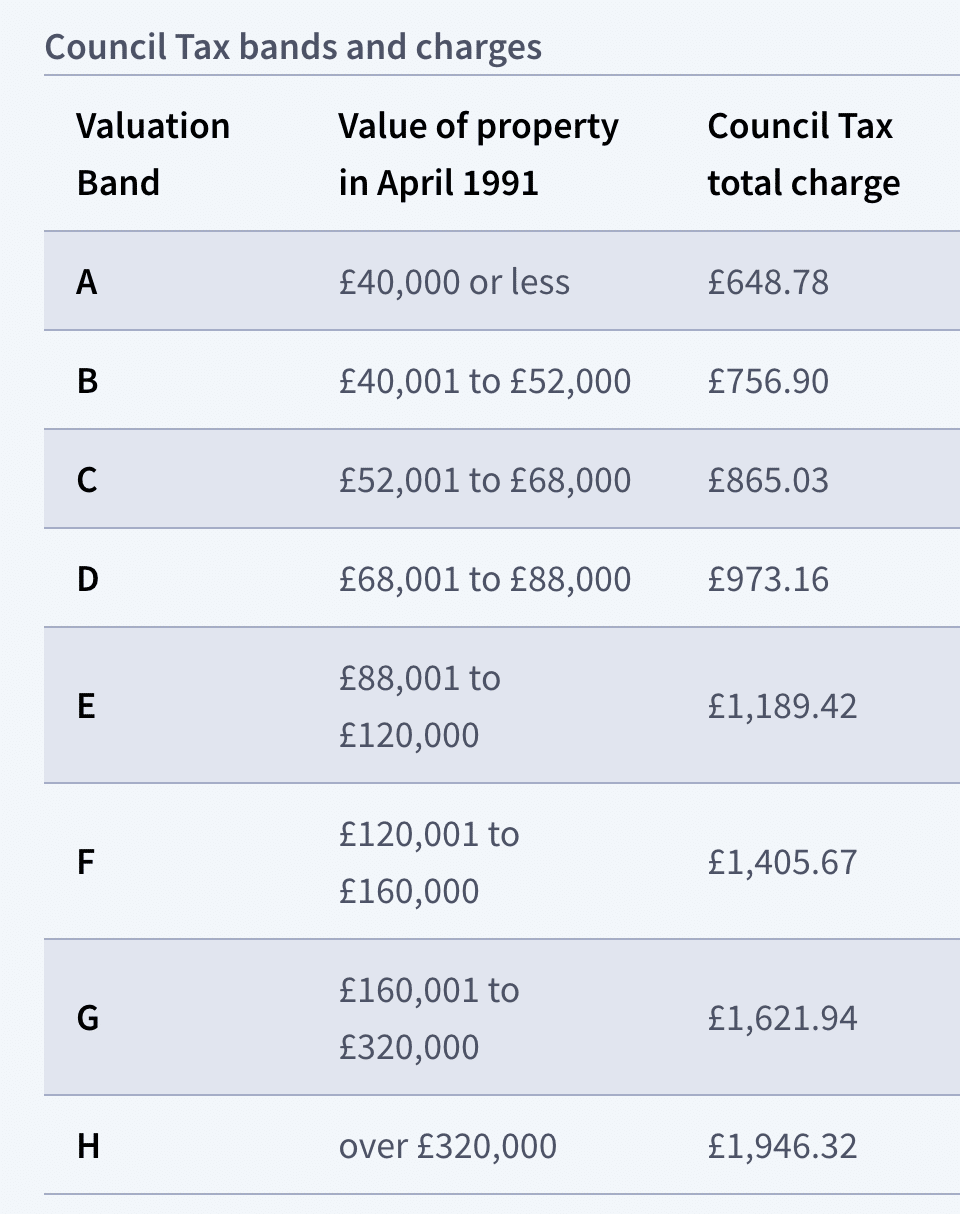

We can see the problem immediately from the Westminster council tax bands:

The bands cap out at £320k – equivalent to about a £2m property today. So there are two bedroom apartments paying the same council tax as a £138m mansion.

And the top Band H rate of £1,946 – restricted by law to twice the Band D rate, is pathetically small compared to the value of many Westminster properties.

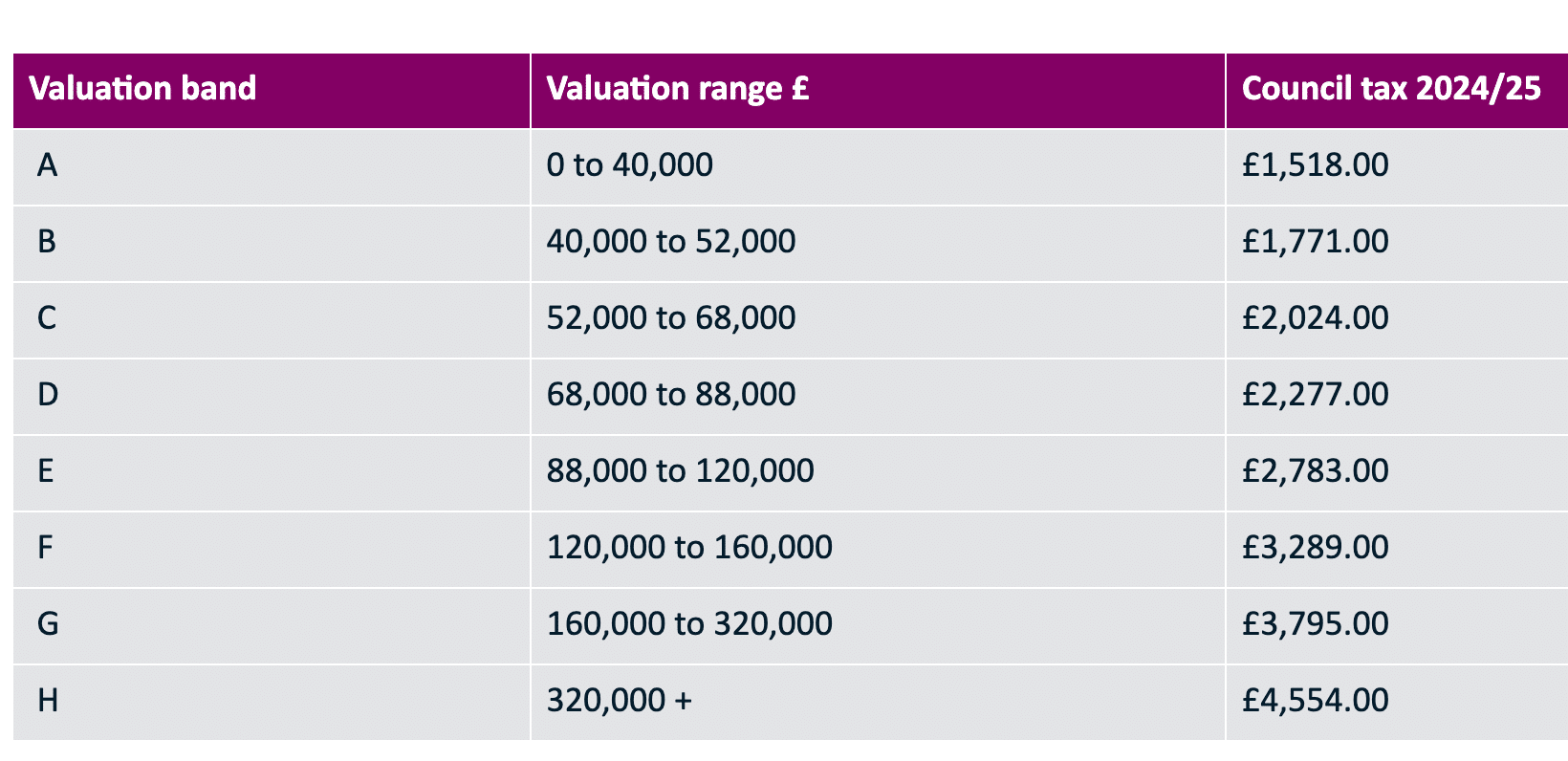

The problem is then exacerbated by the fact that poorer areas tend to have higher council taxes. Here’s Blackpool:

So that £138m mansion pays less council tax than a semi in Blackpool.

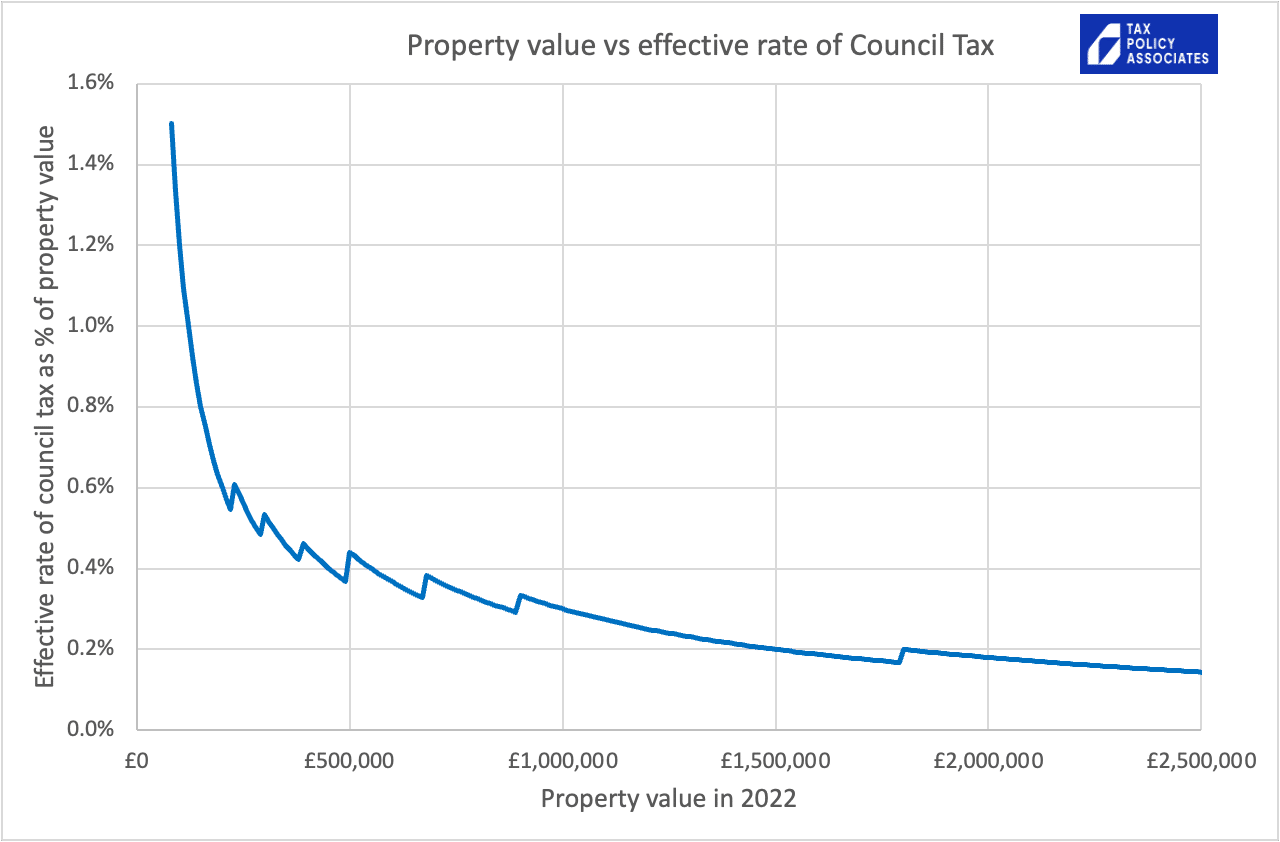

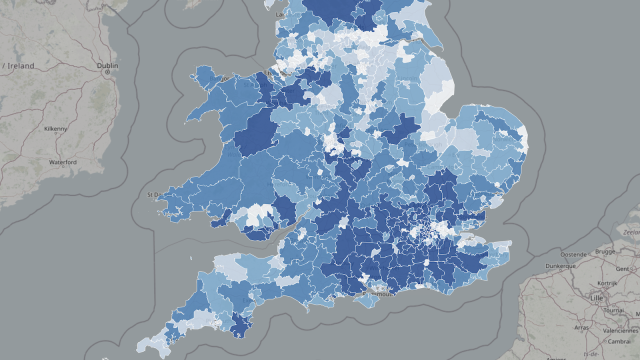

That’s why, if we plot property values vs council tax, we see a tax that hits lower-value properties the most:

In a sane world, this curve would either be reasonably straight (with council tax a consistent % of the value of the property), or it would curve upwards (i.e. a progressive tax with the % increasing as the value increases). This curve is the wrong way up.

Some people look at this and say it’s missing the point – that council tax is a charge for local services, and the owner of the £138m mansion doesn’t use services any more than a tenant in a bedsit. I don’t understand this argument. We don’t view other taxes as charge for local services – why should local taxation be any different?

The problems of council tax are deep-rooted in its design. The solution: abolition.

Abolish business rates

Business rates are based on rateable values, which represent the annual rental value of the property as assessed on a specific valuation date. The rateable value is multiplied by the “multiplier”, currently 54.6% in England and Wales.

This cost will often be higher than it should be.

Rateable valuations are only updated every three years (it used to be every five). That understates the degree to which they are out of date – 2017 revaluation applied rental values as of 1 April 2015 and the 2023 revaluation (delayed by Brexit) applies rental values as of 1 April 2021.

In many retail markets, rents dropped significantly between 2015 and 2019. A landlord could drop the rent to attract tenants, but business rates wouldn’t fall (they’d be “sticky”) and could often end up higher than the rent, making the property unrentable (often with unfortunate consequences). Clearly many factors are responsible for the decline of the high street, but business rates are an important element.

There’s a further problem with business rates. If a tenant improves a property, that increases its rentable value and therefore increases business rates. This creates a disincentive to improve properties – the opposite of what a sensible tax system should do. The previous Government recognised this problem when it introduced an “improvement relief” – but that only delays the uplift in business rates for a year.

The good and bad way to reform business rates

The bad approach is to try to create a level playing field between retailers (who generally occupy high value property, and therefore pay high business rates) and digital businesses (who use out-of-town warehouses with low values, and therefore pay low business rates).

This would be a serious mistake because, while business rate bills are paid by tenants, in the long term the economic incidence of business rates largely falls on landlords⚠️. In other words, business rates reduce the level of market rents.

Rents are usually renegotiated only every 3-5 years, and often upwards-only, so in the short-to-medium term it can be tenants who bear the cost. But a long-term systemic change like increasing business rates on warehouses and reducing it on retail would mostly benefit landlords (after an initial transition period). It would be a spectacular waste of taxpayer funds.

The other not-good approach is a series of sticking-plaster measures bolted onto business rates, none of which deal with the two fundamental problems. That was the previous Government’s approach. It remains to be seen if the new Government will be any better – pre-election, Labour promised to overhaul business rates, but details at this point are scant.

What’s the good way to reform business rates?

Abolition.

A new modern tax on land

There is a much fairer and more efficient way to tax land.

The correct and courageous thing to do is to scrap council tax, business rates and stamp duty – that’s about £80bn altogether – and replace them all with “land value tax” (LVT)6. LVT is an annual tax on the unimproved7 value of land, residential and commercial – probably the rate would be somewhere between 0.5% and 1% of current market values8. This excellent article by Martin Wolf makes the case better than I ever could.

LVT has many advantages. Because it’s a tax on the value of the raw land, disregarding improvements/buildings, it creates a positive incentive to improve land (unlike existing taxes, which do the opposite). And because there is a fixed supply of land (unlike buildings!) the cost of land, i.e. rents – should not increase in response to land value tax. The legal liability to pay would be with the beneficial owner of land9, and they shouldn’t be able to pass that economically onto tenants.10 All taxes hold back economic growth to some degree, but there is good evidence that recurrent land taxes are the most efficient and least harmful.

There are two surprising things about LVT.

The first is that it has support from economists and think tanks right across the political spectrum. How many other ideas are backed by the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Adam Smith Institute, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the New Economics Foundation, the Resolution Foundation, the Fabian Society, the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and the chief economics correspondent at the FT?

The second is that, despite this academic consensus, conventional wisdom says LVT is politically impossible.

I wonder how true that is?

So let’s definitely not implement land value tax. Let’s instead abolish stamp duty and fund it by adding some bands to council tax,11 so it more closely tracks valuations. Most people will pay a bit more tax, but most people won’t pay much more – hopefully they’ll agree it’s worth it to get rid of the hated stamp duty. We’d calibrate this to be neutral overall, so that the end of stamp duty doesn’t just send house prices soaring.12 This is not an original proposal – it was one of the recommendations of the Mirrlees Review in 2010. Paul Johnson of the Institute of Fiscal Studies has also written about it.

Whilst we’re at it, let’s make council tax and business rates both work off the value of the underlying land, disregarding improvements – so people aren’t punished for improving their property.

And let’s update valuations more regularly, so the taxes are fairer. And introduce fair transitional provisions so that nobody is hit by a huge tax increase. We should, in particular, make sure that anyone who recently bought a property and paid SDLT gets a reduction in their LVT for the next few years.13

What we end up with won’t be called “land value tax”, and won’t exactly be a land value tax. But it’s getting awfully close.

These reforms could all be neutral overall, so the same amount of tax is collected across property taxes. That would be my preference. Or some tax could be raised; or there could be tax cuts.

However you do it, there is an opportunity for a big pro-growth tax reform. It might even be popular.

Photo by Sander Crombach on Unsplash

Many thanks K for assistance with the economic aspects of this article.

Footnotes

Apologies to all tax professionals, but I’m going to call SDLT “stamp duty” throughout this article. ↩︎

Strictly semi-elasticities because they are by reference to absolute % changes in the tax rate, not percentage changes in the % tax rate. ↩︎

Another apology to tax professionals. Yes, I know stamp duty and SDLT parted ways in 2003… but the point about the antiquated nature of stamp taxes remains valid. ↩︎

There’s some published research on the 2021 holiday, but it’s qualitative as it was completed too soon to catch the September heart attack. I’m not aware of anything more recent, which is a shame – 2021 was a brilliant double natural experiment. ↩︎

i.e. because tax incidence theory says that where supply is inelastic and demand is elastic, the seller bears the incidence. ↩︎

A quick health warning: many of the people and websites promoting land value tax are eccentric. I once had a lovely discussion with someone from a land value tax campaign. After a while I asked what kind of rate he expected – 1% or 2% perhaps? His answer was 100% (to be fair, 100% of rental value not capital value). Land value tax’s supporters remain one of the biggest obstacles to its adoption. They often suggest income tax/NICs, VAT and corporation tax could all be replaced with LVT – a look at the numbers suggests this is wildly implausible. ↩︎

i.e. as if there was nothing built on it. ↩︎

Meaning a higher % of the unimproved value; but it’s the % of market value that people will care about when the tax is introduced. ↩︎

Failure to pay could result in HMRC automatically gaining an interest in the land via the land registry. ↩︎

A report from the New Economics Foundation suggests landlords will pass on the rent; none of the economists I’ve spoken to agree with that. ↩︎

Significant changes would be required to local government funding formulae, so that the income was pooled appropriately between local and central government, and that Westminster didn’t get an enormous windfall. The wide differentials in property values between local authorities would need to be reflected in the bands, to prevent a scenario where some local authorities have essentially no local property tax at all. ↩︎

i.e. because economically we can expect the present value of future council tax payments to be priced into house prices, and if we increase council tax slightly at the low end and significantly at the high end, we should be able to undo the price effects of abolishing stamp duty. ↩︎

For example allowing the last ten year’s SDLT to be written off over the next over ten years worth of neo-council tax/LVT. So for example someone who paid SDLT nine years ago could get 1/10th of that credited against the new tax (keeping going until the SDLT credit was exhausted). Someone who paid SDLT yesterday could get all of that credited. But this is one of many ways it could work. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Owen Cancel reply