The UK’s 0.5% tax on share transactions is the highest of any major economy. No other country with a major stock exchange has a comparable tax. Stamp duty holds back the FTSE and increases the cost of capital for businesses.

So the reform is very simple: stamp duty on shares should be abolished. A second Boston tea party, but possibly in slow motion. The cost of abolition would plausibly be less than the tax generated from increased share trading and share prices, and the reduced cost of capital for businesses.

This Government was elected on a platform of kickstarting economic growth. It has a large majority, and four or five years until the next election. It’s a rare chance for real pro-growth tax reform. That’s all the more necessary if we are going to see tax rises.

We’ll be presenting a series of tax reform proposals over the coming weeks. This is the second – you can see the complete set here.

Why do we still have stamp duty?

Stamp duty was created in 1671. It made perfect sense. The State had limited power and resources, and collecting tax from people was hard. So some unknown genius had a brilliant idea: impose a tax on documents. No need to have an army of tax inspectors, because if you wanted a document to be used for any kind of official purpose, you’d have to pay to get it stamped.1 Beautiful simplicity – a tax that doesn’t need an enforcement agency.

Stamp duty once applied to basically everything. Even tea2 – which helped spark the American Revolution. Over time, it’s shrunk and shrunk, and today old-fashioned stamp duty is of limited relevance, and we’re mostly talking about “stamp duty reserve tax“, which operates electronically, but still fundamentally works in the same way as the 1671 tax.

So anyone who has bought UK shares will have paid 0.5 per cent stamp duty or stamp duty reserve tax.

There aren’t many countries which have this kind of tax any more:

- France, Italian and Spain have a “financial transaction tax”3 very similar to UK stamp duty, but the rate is lower (0.1% to 0.3%) and it only applies to the largest companies.

- Belgium has a 0.35% tax on share transfers, but capped at €1,600.

- The Finnish and Swiss stamp taxes only apply to domestic transactions and so are easily avoided and are of limited significance.

- Ireland is the only country with a higher rate – 1% – but many observers believe that has significantly damaged its market (even though foreign investors can trade Irish shares free of stamp duty using ADRs).

If we look at the countries with the biggest listed companies: the US4, China, Germany, Hong Kong, Tokyo, India5, Saudi and the UK, the only ones with a stamp duty/FTT is the UK (0.5%) and Hong Kong (0.2%).

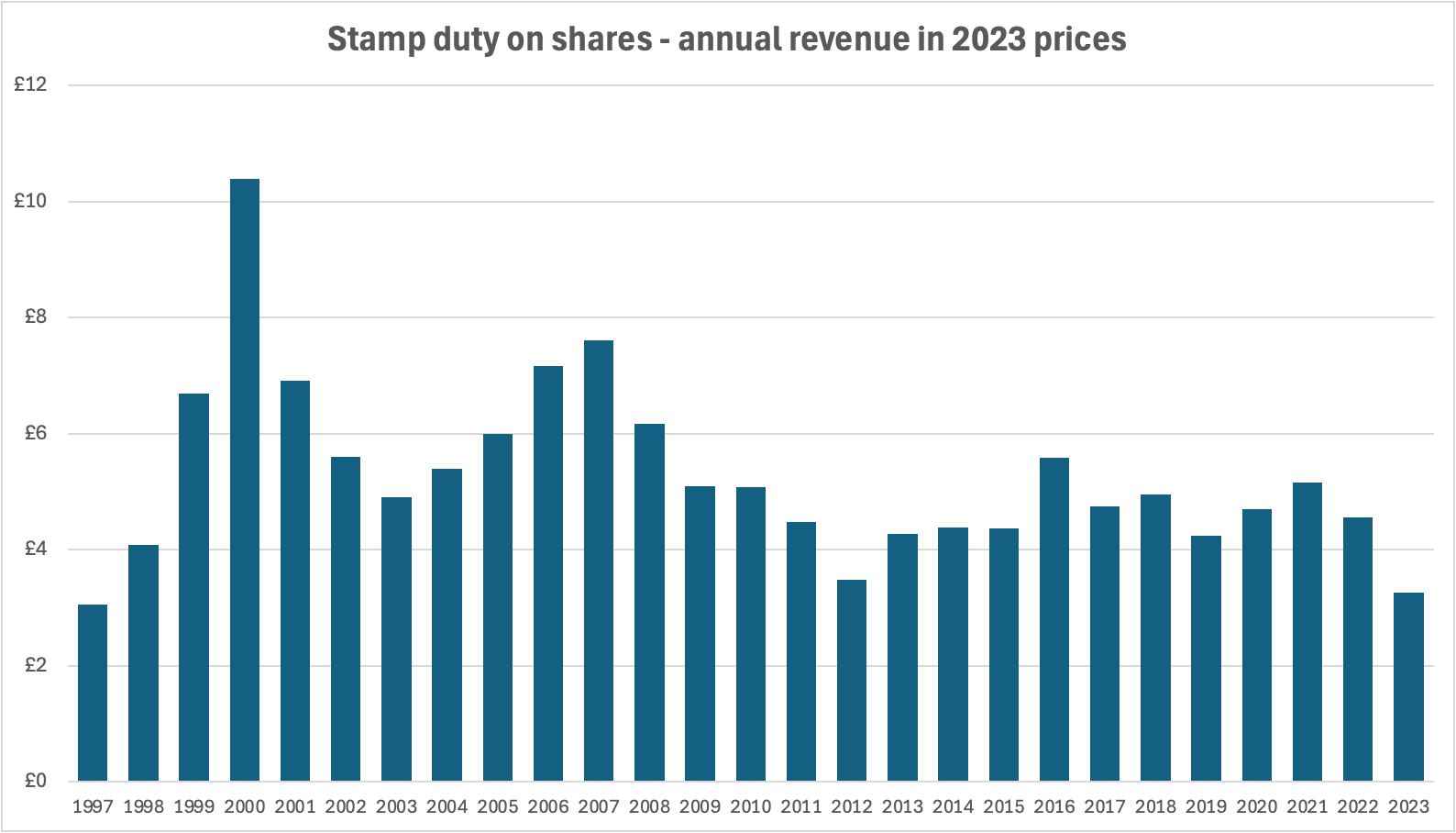

On the face of it, UK stamp duties on shares raise about £4 billion. However, revenues have been declining over time in real terms, reflecting the under-performance of the FTSE:6

Stamp duty may be one of the reasons for the underperformance of the London Stock Exchange – certainly many market participants believe that it is.

What effect does stamp duty have?

It depresses the share price of companies, particularly companies whose stocks are frequently traded.

We can quantify this by looking at what happened in 1990, when the Government announced that stamp duty would be abolished.7 That abolition was put on ice, and this combination of almost-abolition and reprieve creates a nice natural experiment.

Researchers from the IFS were able to quantify the effect in a 2004 paper8, by comparing the relative changes in share price between frequently traded and less frequently traded shares. They concluded that frequently traded shares (broadly meaning larger companies) saw an uplift in share price of between 0.4% and 1.1%. To put that in context, 0.4% of the market cap of the FTSE 100 is £8bn; 1% is £22bn.

Who pays stamp duty?

As a legal matter, the answer is usually the broker buying shares for an investor – the broker or other financial intermediary bears the “legal incidence”.

The broker, whose fee will be tiny fraction of 1%, will inevitably pass on the cost9 to the buying investor. So the investor, at first sight, bears the economic cost, the “economic incidence”.

But the question of who really bears the cost is more messy than that.

First, the structure of stamp duty means that the investor is sometimes exempt. Tax certainly applies if the investor is me, or a pension fund or unit trust. But if the investor is Goldman Sachs’ proprietary trading desk, or (in practice10) a high frequency trading fund, the investor will be exempt. It’s not a tax on the City; it’s a tax on end-investors.11

Second, the fact that share transfers are subject to stamp duty means that the market value of shares is less than it otherwise would be.12 That means that some of the cost of stamp duty is borne by sellers. It also means that some of the cost is borne by the companies themselves – they receive less equity when they issue shares (due to the depressed share price). Stamp duty therefore increases the cost of equity capital.

A distortive tax

The ancient origins of stamp duty mean that it is taxed based on a simple legal definition (shares in UK companies13) rather than on the economic substance of what is happening.

That causes distortions:

- If someone is thinking of establishing a company that will do business in several countries, and the UK is one possible location, stamp duty will (at the margins) mitigate against the choice of the UK.

- Or if you’re establishing a UK company and want to avoid stamp duty anyway, an absolutely classic structure used by private equity and others is to hold a UK company beneath another company (maybe Jersey; maybe Luxembourg) and when you come to sell, sell the Jersey/Luxembourg company.14 This is very hard to stop.15

- Another problem is that stamp duty doesn’t usually apply to the transfer of debt. This means that stamp duty will, at the margins, increase the cost of raising funding through equity rather than debt.

- The fact debt isn’t subject to stamp duty creates a handy loophole. If most of the value of a company is in debt (e.g. shareholder debt) it can be transferred free from stamp duty.

- Public listed UK companies can’t play these games – they don’t usually16 have non-UK holding companies. And obviously public companies don’t have shareholder debt.

This all creates a bias in favour of overseas companies vs UK companies, private companies vs public, and debt vs equity. None of these are desirable.

These issues are discussed in this IFS paper from 2002. At the time the paper was written, stamp duty revenues were soaring. However, we note above, revenues have declined somewhat since then. The case for abolition is therefore stronger than it was in 2002.

The cost of abolition – and the case for slow motion

An IFS paper from 2002 used a simple model to find that increased tax revenue resulting from increased share trading and higher share prices would offset 70% of the cost of abolition. The figures in that paper are consistent with those in the IFS empirical study two years later. A more detailed analysis in a 2024 paper from the Centre for Policy Studies and Oxera found that increased tax revenue would be more than the cost of abolition.17

However it’s the indirect effects on economic growth which are more important. The Oxera paper estimates a permanent increase in GDP of between 0.2% and 0.7%.

There is clearly significant uncertainty here, and an immediate abolition risks a loss of revenue. It would also produce a windfall for current investors (of the kind seen, temporarily, in 1990).

It may therefore make sense to announce a tentative phase-out of stamp duty. For example, a reduction of 0.1% per year over five years, with an review after two years that would continue with the abolition only if there was no adverse revenue impact.

That protects tax revenues during a difficult time; it also has the nice side effect of preventing today’s investors receiving all the windfall from abolition (given there would be genuine uncertainty if the reduction would proceed to complete abolition).

Old-style stamp duty (which is principally relevant for unlisted shares) should simply be abolished overnight. That would put the UK position on par with France and Italy (where private company shares aren’t taxed), as well as eliminating what is currently a cumbersome tax which necessitates expensive UK tax advice on a swathe of transactions where it wouldn’t otherwise be necessary.18 Whilst we’re at it, we should eliminate bearer instrument duty (a tax on UK bearer shares and securities, which no longer exist (except in some technical cases19 where the duty doesn’t apply anyway).20

The politics

The case for abolishing stamp duty is clear. No other major economy has a tax as high and as broad in scope as ours. It makes the UK a less attractive market/listing venue, and increases the cost of capital for British companies. And it’s not paid by City institutions — the burden falls on ordinary investors (and their ISAs and pension funds) and on businesses trying to raise capital.

The problem is that, on the surface, abolishing stamp duty looks like a giveaway to the wealthy. Any Tory doing it could expect to be (unfairly and inaccurately) carpeted by Labour for giving a handout to the rich.

But, just as only President Nixon could go to China, perhaps only Labour can abolish stamp duty.

Engraving of the Boston Tea Party by E. Newbury, 1789, photo by Cornischong

Footnotes

No official would accept an unstamped document, for fear of being thrown into jail. That principle is still there in the Stamp Act 1891, which remains in force. ↩︎

Technically this was the Townshend Acts not the Stamp Act ↩︎

Not really an FTT, which is a very different beast ↩︎

The SEC charges a fee of currently $27.80 per million dollars per trade. But that very low level (0.00278%) means it can’t be sensibly compared with the taxes other countries charge. ↩︎

I’m disregarding India’s very small stamp duty on listed shares, as it’s only 0.015%⚠️. ↩︎

Data from ONS, chart by Tax Policy Associates. ↩︎

The reason for abolition is curious: the Stock Exchange’s planned new software system for paperless trading, Taurus, couldn’t cope with stamp duty. Taurus failed for unrelated reasons, which meant that stamp duty won a reprieve. The eventual solution, CREST, incorporated a modern electronic version of stamp duty, SDRT. ↩︎

The paper also looks at the impact of the rate reductions in 1984 and 1986, but the data is less good and so the results less reliable. ↩︎

Or at least almost all of it ↩︎

Because of various arrangements, of various degrees of dubiousness, that I should write about at a later date ↩︎

This is inevitable given the way financial transactions work; attempting to tax financial intermediaries is doomed to fail – I explained why in this old piece for my former firm. ↩︎

If you don’t believe that, imagine stamp duty was suddenly increased. Share prices would, logically, fall overnight. And see above for what happened to share prices when stamp duty was (almost) abolished. ↩︎

It’s more complicated than this in theory – I went into this in detail here – but in practice “shares in UK companies” is a good approximation of the truth. ↩︎

Why do sellers care about stamp duty? Because economically, on the sale of a private company, we can expect the cost to be shared between buyer and seller (with buyer paying the duty, and seller receiving a smaller price). ↩︎

An anti-avoidance rule was introduced in 2016 to stop the then-common practice of avoiding stamp duty by cancelling and reissuing shares. However it’s not obvious how rules could stop “enveloping” companies without unwanted knock-on effects on normal commercial transactions… which is probably why none of the other countries with similar taxes have such rules. ↩︎

Stock exchange rules and the requirements for a premium listing mean that UK listed companies in practice are usually UK incorporated. ↩︎

The figures for the impact on share prices in the Oxera paper are derived theoretically and considerably higher than those in the 2004 IFS empirical study. That doesn’t mean they are wrong; the data analysis in the IFS paper was necessarily limited by its design, and relates to a period (1990) where trading volumes were significantly lower than the present day. ↩︎

More details in this OTS paper and this paper from Sara Luder and the IFS Tax Law Review Committee. ↩︎

i.e. cleared securities ↩︎

I asked HMRC in a Freedom of Information Act application for the total revenue from bearer instrument duty; they didn’t know, but suspected there was none. I’ve spoken to senior Treasury officials aren’t weren’t even aware bearer instrument exists. ↩︎

Leave a Reply