Stamp duty is a terrible tax. The Tories want to abolish it for most first time buyers. But the evidence shows that cutting stamp duty increases house prices, and that previous attempts to provide relief for first time buyers were ineffective.

Council tax is also terrible tax – with Buckingham Palace paying less council tax than a semi in Blackpool.

We can solve both problems together, and tax land in a way that encourages housebuilding and economic growth. But that requires smart thinking and brave politics.

The problem with stamp duty

Stamp duty land tax (SDLT)1 is a deeply hated tax.

It reduces transactions2, distorts the housing market, and often stops people moving when they want to. Stamp duty makes it harder to borrow from a bank (because the stamp duty is “lost value”). All of this means it reduces labour mobility, results in inefficient use of land, and plausibly holds back economic growth.

And the rates are now so high that the top rates raise very little; HMRC figures suggest that increasing the top rate any further would actually result in less tax revenue.

It also makes people miserable.

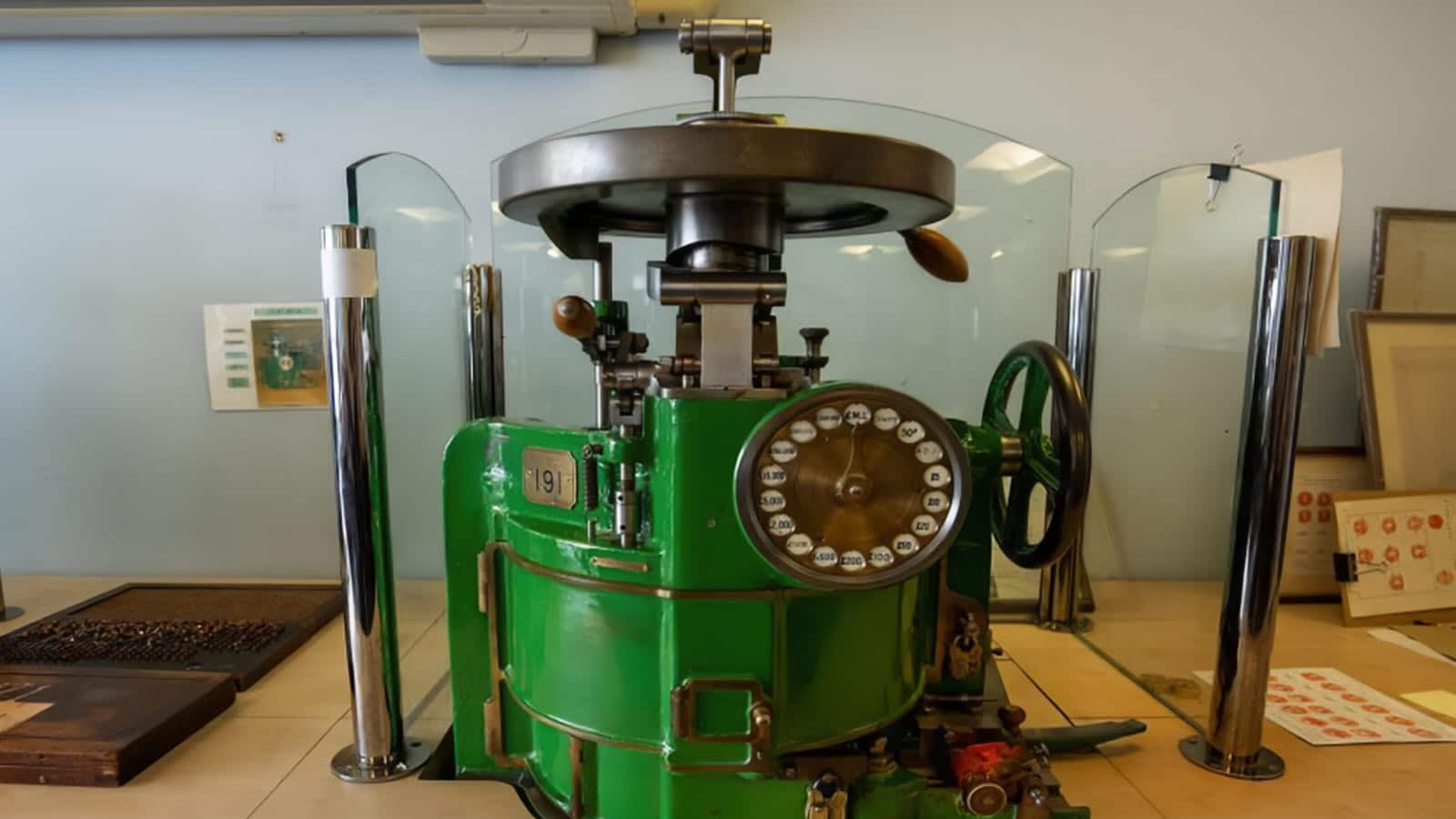

Stamp duty only exists because, 300 years ago, requiring official documents to be stamped was one of the only ways governments of the time could collect tax. We have much more efficient ways to tax today – but stamp duty remains. Until four years ago HMRC even still used the Victorian stamping machine in the picture at the top of the page.3

The problem is that, like many bad taxes, politicians have become addicted to it. SDLT now raises £12bn each year – an amount that’s hard to ignore.

And there’s an even worse problem: abolition would inflate property prices.

The problem with abolishing stamp duty

The link between stamp duty and prices is clear when we look at the impact on house prices of the stamp duty “holidays” in 2021:

The spikes in June and September coincide with the ends of the “holidays”. A rush of people to take advantage of the discounted stamp duty.

Of course the “holidays” were temporary – but the chart suggests that there was a permanent upwards adjustment in house prices (probably due to the “stickiness” of house prices).

Previous stamp duty holidays had less dramatic effects. There’s good evidence that the 2008/9 stamp duty holiday did lead to lower net prices, but 40% of the benefit still went to sellers, not buyers. I’d speculate that the difference is explained by the much lower stamp duty rates at the time.4

A detailed Australian study looked at longer-term changes than the recent UK “holidays” – it found that all the incidence of stamp duty changes fell on sellers (and therefore prices). This is what we’d expect economically in a market that’s constrained by supply of houses.5

These effects mean that stamp duty cuts aimed at first time buyers may end up not actually helping first time buyers. An HMRC working paper found that the 2011 stamp duty relief for first time buyers had no measurable effect on the numbers of first time buyers.

The problem with council tax

Stamp duty isn’t our only broken property tax. Council tax is hopeless – working off 1991 valuations, and with a distributional curve that looks upside down.

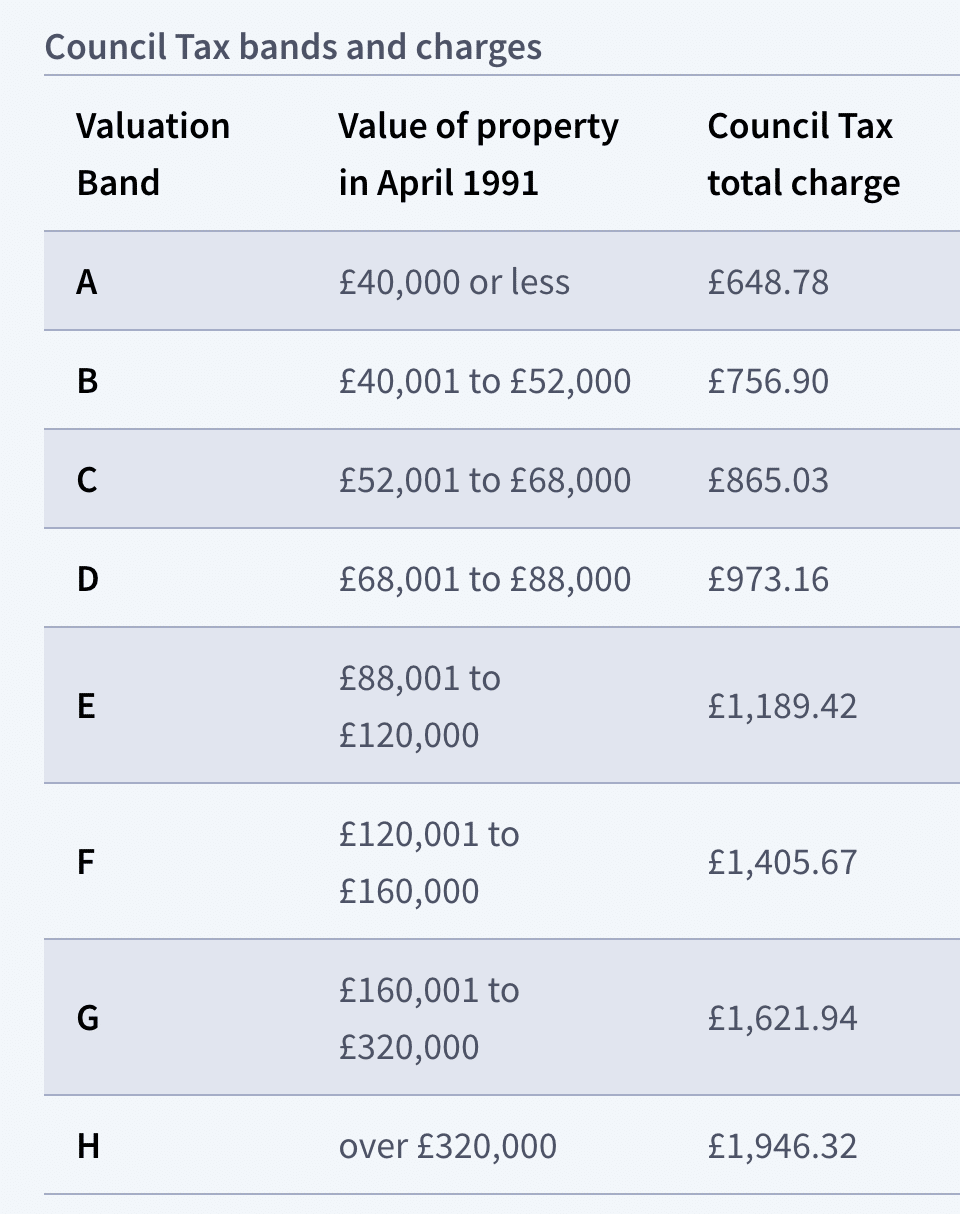

We can see the problem immediately from the Westminster council tax bands:

The bands cap out at £320k – equivalent to about a £2m property today. So there are two bedroom apartments paying the same council tax as Buckingham Palace.6

And the top Band H rate – restricted by law to twice the Band D rate, is pathetically small compared to the value of many Westminster properties.

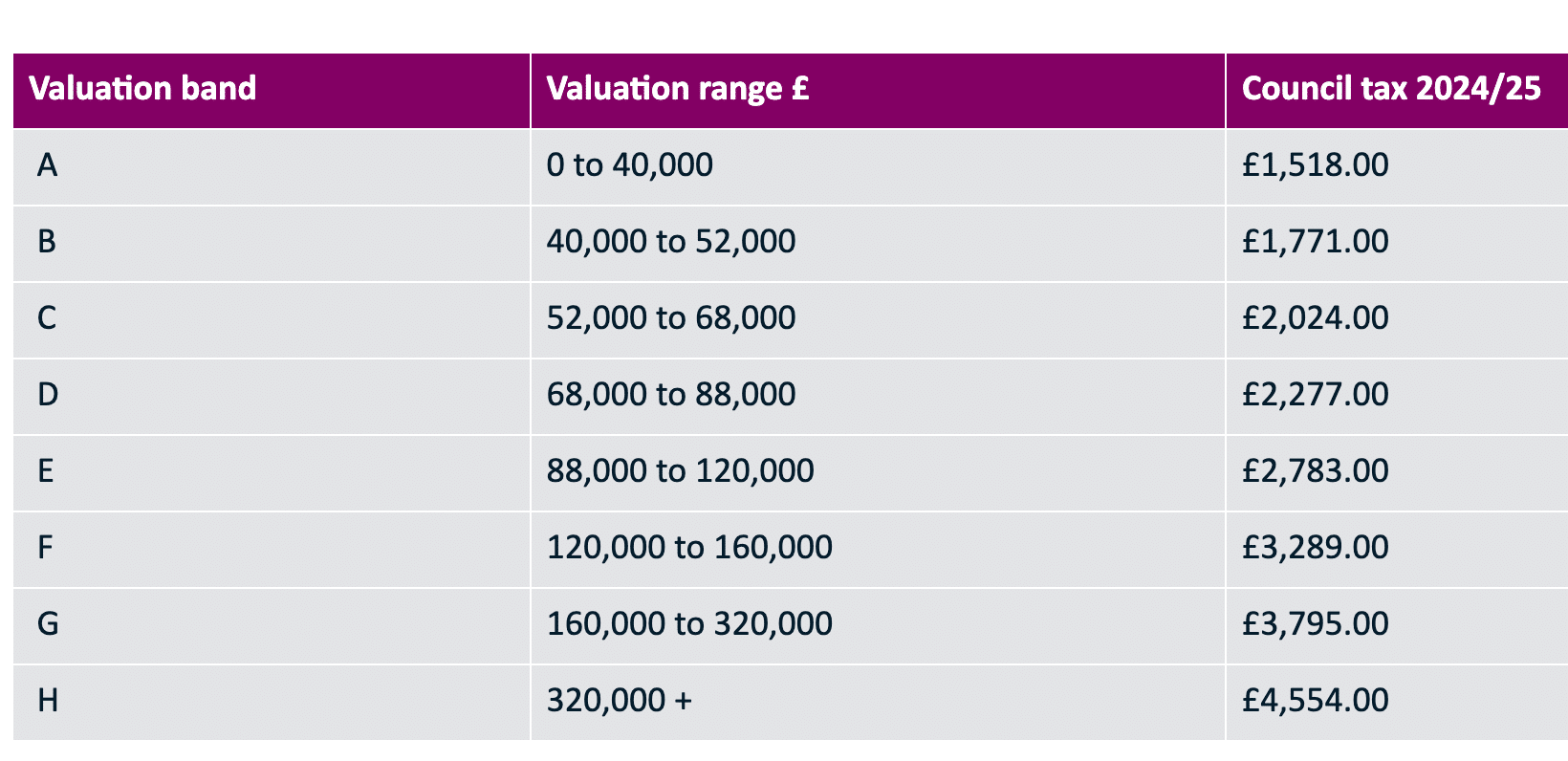

The problem is then exacerbated by the fact that poorer areas tend to have higher council taxes. Here’s Blackpool:

So Buckingham Palace pays less council tax than a semi in Blackpool.

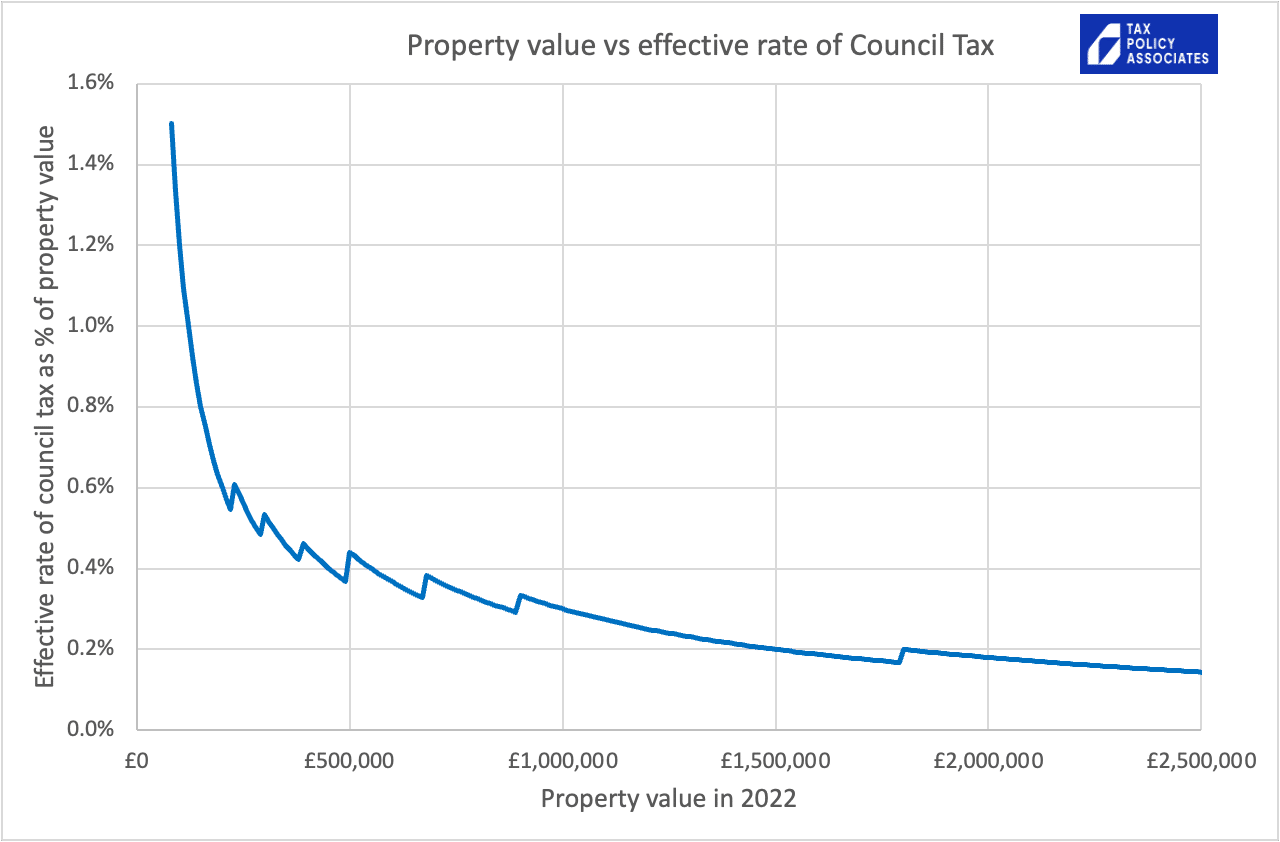

That’s why, if we plot property values vs council tax, we see a tax that hits lower-value properties the most:

In a sane world, this curve would either be reasonably straight (with council tax a consistent % of the value of the property), or it would curve upwards (i.e. a progressive tax with the % increasing as the value increases). This curve is the wrong way up.

The solution

The solution is to fix council tax and stamp duty at the same time.

Abolish stamp duty altogether, and change council tax to make it fairer… calibrating that change so that end of stamp duty doesn’t just send house prices soaring.7 This is not an original proposal – it was one of the recommendations of the Mirrlees Review in 2010. Paul Johnson of the Institute of Fiscal Studies has also written about it.

But we can go further. The really courageous answer is to scrap council tax, business rates and stamp duty – that’s about £80bn altogether – and replace them all with “land value tax” (LVT)8. LVT is an annual tax on the unimproved9 value of land, residential and commercial – probably the rate would be somewhere between 0.5% and 1% of current market values10. This excellent article by Martin Wolf makes the case better than I ever could.

There are two amazing things about LVT.

The first is that it has support from economists and think tanks right across the political spectrum. How many other ideas are backed by the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Adam Smith Institute, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the New Economics Foundation, the Resolution Foundation, the Fabian Society, the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and the chief economics correspondent at the FT?

The second is that everyone says it’s politically impossible.

I wonder how true that is.

So let’s definitely not do land value tax. Let’s instead abolish stamp duty and fund it by adding some bands to council tax, so it more closely tracks valuations. Most people will pay a bit more tax, but not much more – and it’s worth it to get rid of the hated stamp duty. Whilst we’re at it, let’s update valuations more regularly, so it’s fairer. And why not make it apply to the unimproved value of land, so people aren’t punished for improving their property?

Everyone agrees business rates need reform – so let’s make similar changes to business rates.

What we end up with won’t be called “land value tax”, and won’t exactly be a land value tax. But it’s getting awfully close.

The price

That’s the price of abolishing stamp duty: some of us have to pay a bit more council tax (or, in my fantasy world, land value tax)11. That’s worth doing for a saner housing market that doesn’t hold back growth. And a land value tax should encourage house-building and actually boost growth.

But if all we do is abolish stamp duty, most or all of the tax saved by buyers will be eaten up in higher property values. It becomes a £12bn government handout to sellers.

There’s no free lunch. But there is an opportunity for a big pro-growth tax reform. It might even be popular.

Photo of original stamping machine is Crown copyright, and reused here under the Open Government Licence

Many thanks K for assistance with the economic aspects of this article.

Footnotes

Apologies to all tax professionals, but I’m going to call SDLT “stamp duty” throughout this article. ↩︎

The elasticities found in HMRC research are incredible; a 1% change in the effective tax rate results in almost a 12% change in the number of commercial transactions and a 5-7% change in the number of residential transactions. (Strictly semi-elasticities because they are by reference to absolute % changes in the tax rate, not percentage changes in the % tax rate). ↩︎

Hello tax professionals. Yes, I know stamp duty and SDLT parted ways in 2003… but the point about the antiquated nature of stamp taxes remains valid. And I like the picture. ↩︎

There’s some published research on the 2021 holiday, but it’s qualitative as it was completed too soon to catch the September heart attack. I’m not aware of anything more recent, which is a shame – 2021 was a brilliant double natural experiment. ↩︎

i.e. because tax incidence theory says that where supply is inelastic and demand is elastic, the seller bears the incidence. ↩︎

Meaning the Royal Residence at Buckingham Palace – most of the rest of the complex isn’t a dwelling, and pays business rates not council tax. I haven’t seen any data on the value of the Royal Residence, but safe to assume it is very high indeed. ↩︎

i.e. because economically we can expect the present value of future council tax payments to be priced into house prices, and if we increase council tax slightly at the low end and significantly at the high end, we should be able to undo the price effects of abolishing stamp duty. ↩︎

A quick health warning: many of the people and websites promoting land value tax are eccentric. I once had a lovely discussion with someone from a land value tax campaign. After a while I asked what kind of rate he expected – 1% or 2% perhaps? His answer was 100%. Land value tax’s supporters remain one of the biggest obstacles to its adoption. They often suggest income tax/NICs, VAT and corporation tax could all be replaced with LVT – a look at the numbers suggests this is wildly implausible. ↩︎

i.e. as if there was nothing built on it. ↩︎

Meaning a higher % of the unimproved value; but it’s the % of market value that people will care about when the tax is introduced. ↩︎

That would be quite unfair on someone who has just paid a large SDLT bill to buy an expensive property – they get punished under the new rules and the old. It would make sense to give some form of relief for recent SDLT… for example allowing SDLT to be written off over ten years worth of neo-council tax/LVT. So for example someone who paid SDLT nine years ago would get 1/10th of that credited against the new tax for one year. Someone who paid SDLT yesterday would get 1/10th of that credited for each of the next ten years. But this is one of many ways it could work. ↩︎

![t 1] E SHARING BEST PRACTICE

proper y .S FOR UK LANDLORDS & PRS

The Ultimate Guide to

LANDLORD TAX PLANNING

and transitioning between ownership structures](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Untitled.jpg)

Leave a Reply to Xavier Cancel reply