The Lib Dems are proposing a 4% tax on share buybacks that they say would raise £1.4bn/year. It’s based on a similar proposal in America. But circumstances in the US and UK are very different. This means that the rationale for the US tax isn’t relevant to the UK and, more importantly, that the Lib Dem proposal would raise much less than £1.4bn. It’s plausible it could raise almost nothing.

UPDATED 9 June 2024 to reflect the latest Lib Dem proposal, which ups the main estimate to £2.2bn, but then knocks £800m off out of “caution”. There’s also a fair take on this from fullfact.org here.

The US tax benefit of buybacks

In 2022, the US imposed a 1% excise tax on share buybacks.

Why?

Primarily because two significant classes of investors in US shares receive a tax benefit from buybacks as opposed to dividends:

- US retail investors directly1 hold about a third of the US equity market. Dividends they receive are taxed at up to 23.8% (plus State income taxes, where applicable). Capital growth from a buyback isn’t taxed immediately at all. Some investors will never sell and the gains will never be taxed; if they do sell, long term capital gains are taxed at 20% (plus any State capital gain taxes).

- Foreign investors hold about 16% of the US equity market. The US imposes a withholding tax on dividends that ranges between 15% (for investors in countries with a favourable tax treaty with the US) and 30% (the worst case). But a buyback increases the value of an investor’s shares; any capital gain made on a subsequent sale by a foreign investor is not subject to US tax at all.

We can therefore make a rough estimate that paying profit out as a buyback rather than a dividend means a reduction in overall US tax paid of somewhere between 4% and 14% of the amount of the buyback.2

It is therefore not that surprising that the 1% buyback tax did not noticeably reduce the volume of buybacks – the tax is significantly less than the tax benefit.3

How high would the buyback tax have to be to equalise the tax treatment? There is no simple answer, given the diversity of investors and their tax positions, but the simple calculations above suggest the answer is at least 4%.4

It is therefore probably not a coincidence that President Biden is now proposing to increase the tax to 4% (although we understand that this has little chance of becoming law in the current US political environment).

The UK tax benefit of buybacks

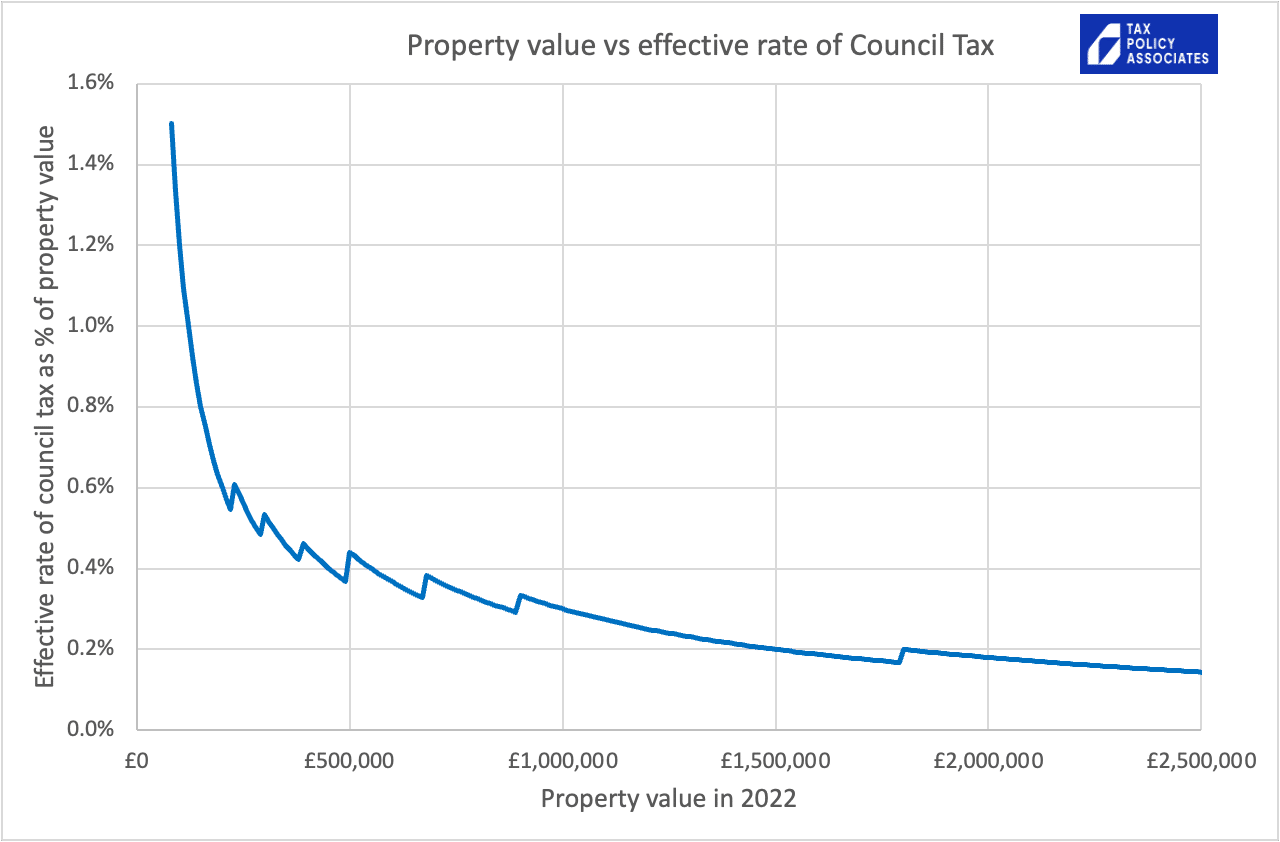

The differences between US and UK stock markets and tax rules mean that buybacks by listed companies5 have very little tax benefit in the UK.

- UK individual investors who hold onto their shares6 have a big tax benefit from buybacks, as their eventual capital gain would be taxed at 20%, but dividends taxed at a top rate of 39.35%. However UK individual investors directly hold only about 4% of the UK equity market;7 another 7% is held through ISAs but, as ISAs aren’t taxable, these investors have no preference for buybacks vs dividends.

- UK companies hold a small proportion of the equity market (1.4% in the 2020 figures). If they participate in a buyback then the position is the same as if they had received a dividend – it’s exempt. If they don’t, then buybacks provide them with a worse tax treatment: corporate capital gains are taxed at 25% but dividends are exempt.8

- Foreign investors hold almost 60% of UK listed shares, but the UK doesn’t tax them on either dividends or capital gains.

We can therefore make a rough estimate that paying profit out as a buyback rather than a dividend means a reduction in overall UK tax paid of about 0.8% of the amount paid out in the buyback.9 This is pleasingly close to the existing 0.5% stamp duty charged on buybacks, leaving a surplus benefit of probably no more than 0.3%.

It is therefore unsurprising that, whilst tax is often cited as a driver of US buybacks, it is not usually cited by market observers as the reason for UK buybacks.10

The consequences

The lack of a material tax benefit from UK buybacks has two important consequences.

First, it makes it hard to understand the rationale for a buyback tax. If the Lib Dems want to increase tax on companies, they could increase corporation tax (although I would be sceptical this is a good idea right now).

Second, it means that the Lib Dems’ revenue projection is wrong.

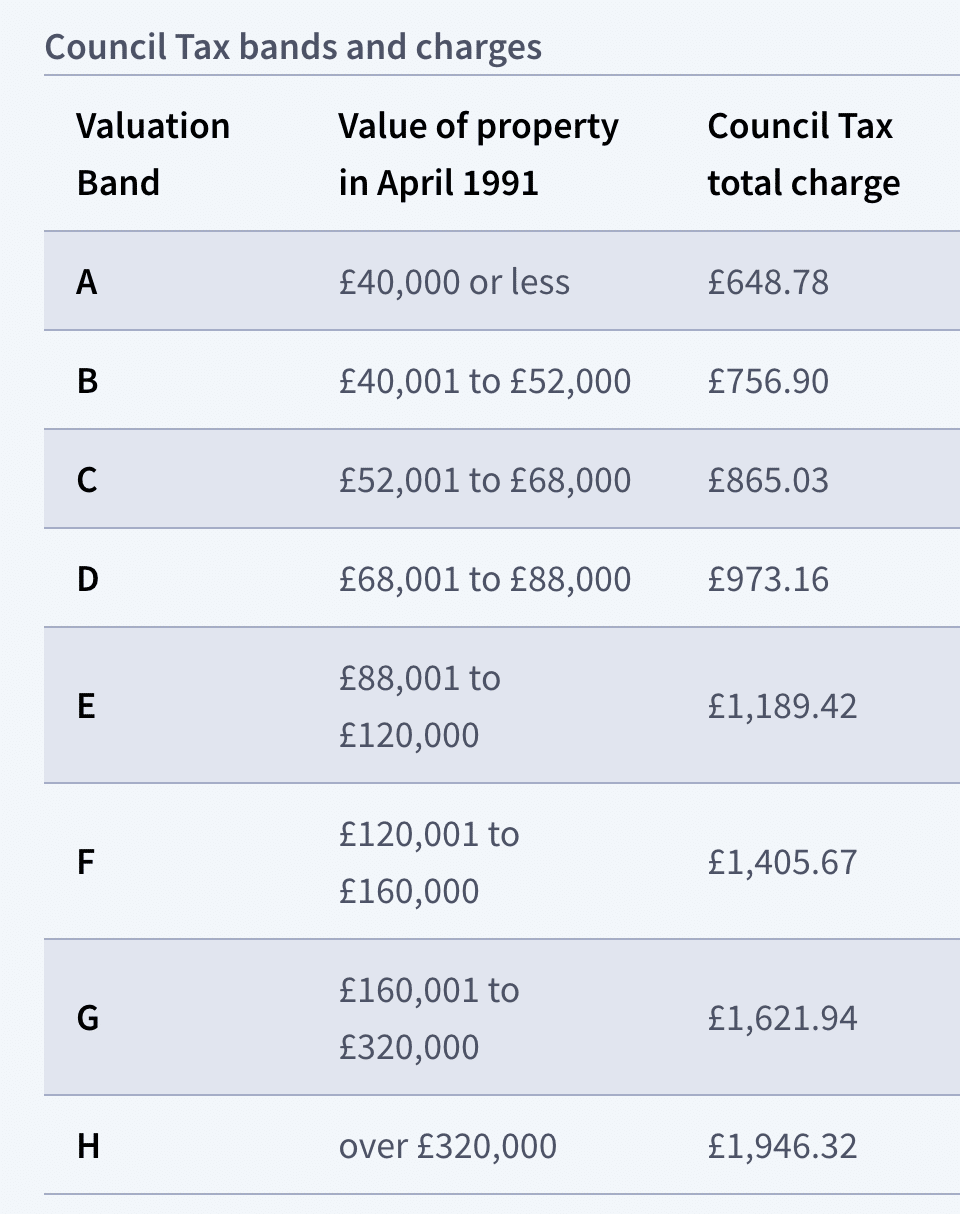

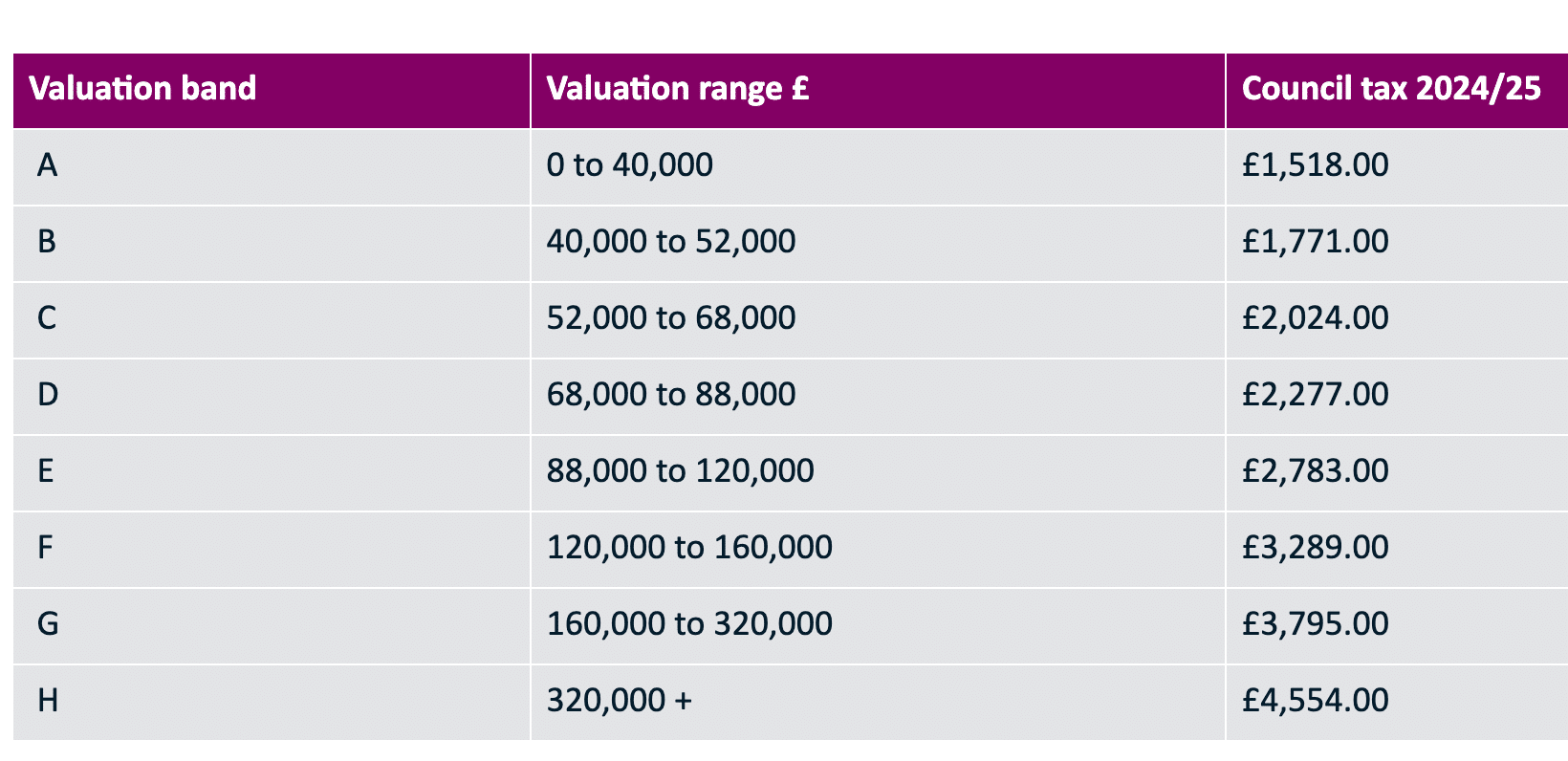

The Lib Dems say their 4% tax would raise £1.4bn annually. They haven’t published their methodology – they just say this:

It’s reasonably clear all they’ve done is multiply 4% by the approximately £50bn volume of buybacks in 2022 and 2023, to come up with a static estimateo f £2.2bn. They then “take a cautious approach to account for potential changes in company behaviour”, and reduce this to their claimed £1.4bn.

That is, however, not a realistic basis for estimating the revenues for a tax. You have to properly take into account the taxpayer response – the tax elasticity.1112 If we impose a £10,000 tax on men with beards then we cannot calculate the revenue as (£10,000 x 15 million men with beards). There would be an obvious taxpayer response (shaving), and the actual revenue would be close to zero.13

In the case of buyback taxes there is an equally obvious taxpayer response – paying a dividend instead of buying back shares.

The Lib Dems cite an IPPR paper from 2022 which proposed a 1% tax on buybacks. The IPPR said their proposal would raise £225m, using the same simple methodology now adopted by the Lib Dems, but with an important caveat:

And the IPPR explicitly warned about the risk of a higher tax:

The current US buyback tax at 1% is considerably lower than the overall tax 4% to 14% tax benefit from buybacks. Biden’s new proposal at 4% approaches the bottom-end estimate, but does not exceed it, and that is surely deliberate. So it would be rational to expect the 4% tax to somewhat reduce the volume of buybacks, but only to a degree.

The Lib Dem tax is very different, because it is at least four times greater than the tax benefits of buybacks (particularly once we take account of the existing 0.5% stamp duty). There are other benefits of buybacks; they can be more flexible, and they send out price signals (inflating EPS but without a “real” economic effect).14 It is not at all obvious that these, rather ephemeral,15 benefits are worth 3% of the value of a buyback.

The natural conclusion is that a 4% buyback tax will simply result in companies switching from buybacks to dividends. And because 95% of investors receive no tax benefit at all from buybacks, but would bear the cost of the 4% buyback tax, there would likely be significant shareholder pressure to drop buybacks entirely.

The other justification provided for the tax is that it would increase investment. This doesn’t make any sense. If a company has decided to return cash to investors then a buyback tax may incentivise it to move to a dividend; it’s unclear why it would incentivise it to retain the cash. It also seems simplistic to regard cash retained by a company as investment, but cash returned to shareholders as simply disappearing.

So the cautious estimate is not £1.4bn – it’s nothing.

We agree with Stuart Adam from the Institute of Fiscal Studies:

That is, however, not the end of the analysis, because there are second order effects:

- Buybacks are currently subject to 0.5% stamp duty/stamp duty reserve tax. So an end to buybacks would mean a loss of c£250m of stamp duty revenue.

- An end to buybacks means more dividends, so the c4% of UK individuals directly holding shares would pay more income tax. On the basis of our top-end estimate above, this amounts to somewhere less than 0.8% of buyback values i.e. £400m of additional tax revenue.

- Then there are the costs to Government/HMRC of creating the tax, and the cost to business of complying with it.

We don’t have enough data to properly estimate the net result of these effects. They would probably be small, but the direct revenues from the tax would also probably be small.

There are many historical examples of people taxing shares without thinking through how people would respond. These usually ended badly – the Swedish financial transaction tax and US interest equalisation tax are the most notorious examples.

The general rule remains that your motive for introducing a tax is irrelevant. The key questions are: what will happen in practice? What incentives are you creating? How will people respond?

It’s all very tedious. It’s also necessary.

Photo of Ed Davey by Dave Radcliffe, licensed under Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Footnotes

“directly” meaning this is excluding holdings through ETFs, mutual funds and pensions, which have different tax treatment ↩︎

i.e. because the minimum saving will be (34% x 3.8% + 16% x 15%) and the maximum saving will be (34% x 23.8% + 16% x 30%). This ignores State taxes and a large number of other complications, so should be regarded as no more than a very rough approximation ↩︎

In principle one might say that there should be a different result, because the majority of investors in US equities obtain no tax benefit from buybacks, but now suffer the cost of the excise tax, and they could be expected to agitate against buybacks. A plausible answer is that retail investors have an outsize influence. ↩︎

After writing the first draft of this piece, we found this analysis by the left-leaning Tax Policy Center, which uses different data and a slightly different approach but also concludes the answer is around 4%. ↩︎

There is a separate question about unlisted/private companies engineering a return of capital rather than a dividend to obtain a tax advantage, i.e. because of the large differential between the 39.35% top rate of income tax on dividends and the 20% capital gains tax rate. The Lib Dems aren’t proposing to tax private companies but, even if they were, a buyback tax would not come close to reversing this benefit. The more effective and simpler answer would be a specific anti-avoidance rule. ↩︎

Investors whose shares are bought back are mostly taxed on the buyback as income, as generally only the nominal value of the share is treated as a capital gain. Hence a rational UK individual investor will not take-up a buyback; the tax treatment is much worse than simply selling their shares in the market. ↩︎

UK individual investors hold about 11% of the UK listed market, equating to about £250bn. However ISA investors hold about £400m of stocks/shares and have a 37% weighting towards the UK, implying they hold about £150bn of UK equities. Thus only 40% of UK individual investors’ holdings in UK listed equities are held directly. ↩︎

There are exceptions to both rules, but for listed companies the exceptions generally won’t apply. ↩︎

i.e. because 4% x 19.35% = 0.8%, but that’s a top-end estimate because many investors won’t pay the additional rate, and any investors actually participating in the buyback pay more tax as a result. ↩︎

As an aside, whilst it’s a very good idea to benchmark tax policy proposals against other countries’ experiences, it’s dangerous to assume that a tax policy that’s successful in one country will also be successful in another. There are a myriad of tax, legal and societal reasons why that is often not the case. In this instance it’s the difference between the US and UK markets plus the difference in the tax treatment of foreign investors – both are sizeable differences, and together they make the buyback landscape in the US markedly different from the UK ↩︎

There has been research into the impact of stamp duty on share trading, and the elasticity of share prices with respect to transaction costs. In principle similar research could look at the impact of existing stamp duty on buybacks (by reviewing data from when the rate changed from 1% to 0.5% in 1986. However I’m not aware of anyone doing this; possibly the volume of buybacks around 1986 was too small to make this feasible. ↩︎

There are other problems with the estimate. The US buyback tax exempts certain types of mutual funds because they engage in buybacks to minimise their share price discount vs their NAV. Realistically a UK buyback tax would have to exempt investment trusts, and probably create other exemptions too. So the £2.2bn estimate is wrong even if we ignore elasticity/taxpayer response, but elasticity is by far the most important effect. ↩︎

Not quite zero, because some people would make a mistake; some people would try and fail to avoid the tax (with complex boundaries between moustaches and beards, and difficult caselaw around false beards). And having a beard would become a signal of enormous wealth ↩︎

It’s sometimes suggested that buybacks are used by executives to manipulate their own remuneration targets. This would be possible in theory if executive remuneration packages are not designed and implemented carefully. A detailed study looked at the FTSE 350 to see if there was evidence of buybacks inflating executive pay – it found that there was not. ↩︎

Warren Buffet said “When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive).” ↩︎