Since our original report, we’ve received numerous reports of clients’ and advisers’ experiences with Property118. This short report explains one new element – the artificial creation of a “director loan” which can be used by landlords to take profits from their business free from income tax.

It’s an artificial tax avoidance scheme which doesn’t work, and any landlord using it will incur large tax liabilities and penalties. The scheme should have been disclosed to HMRC under the “DOTAS” rules, but wasn’t – Property118 potentially face penalties of up to £1m.

UPDATE 13 October 2023: since we wrote this report we’ve discovered more about the precise details of this scheme, which means that the description and analysis below is both inaccurate and too kind. We’ll keep this here, but our updated full description of the scheme is here.

The sales pitch

Here’s the sales pitch from Property118:

We’ve redacted the figure to protect our source, but it’s a large six figure sum.

Here’s their explanation:

This just one example from the many we’ve received – it’s a standardised structure. Property118 even set out the details themselves here.

What’s going on?

When a company makes a profit, it pays corporation tax. If it then pays the profit to its shareholders as a dividend, they pay tax on that. But if it can use the profit to repay a loan from the shareholders then they don’t pay tax on the loan repayment.

Standard (and legitimate) tax planning on incorporation takes advantage of that. In the standard approach, the landlord sells property to the newly incorporated company in return for (1) shares, (2) assumption of mortgage debt, and (3) a “loan note”1 (or similar) issued by the company to the landlord. Future profits can be used to repay the loan note.

That is uncontroversial, but has the disadvantage that the sale of the property to the company will be subject to capital gains tax.

Property118 think they’ve found a way to avoid the capital gains tax and extract profits by a tax-free loan repayment.

Here’s an example. Let’s take a landlord who owns properties worth £1m and has a mortgage of £500k.

Step 1: Landlord takes out a two week bridge loan of £450k. The money never actually goes to the landlord – it’s held in a solicitor’s client account. The solicitor undertakes to the lender that the money will never leave that account (so the arrangement is risk-free for the lender):

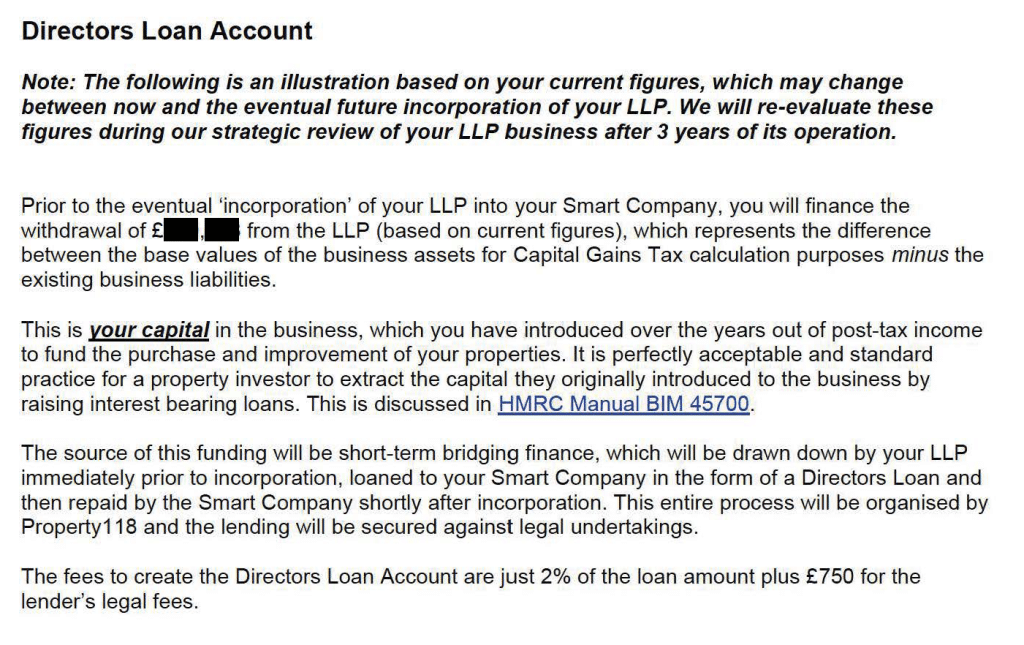

Step 2: Landlord incorporates a new company. The company buys the rental properties, and in return issues £50k of shares to the landlord, and agrees to assume responsibility for the £500k mortgage and the £450k bridge loan (under a “novation”). Note that the £450k advanced under the bridge loan stays with the landlord (in the solicitor’s client account):2

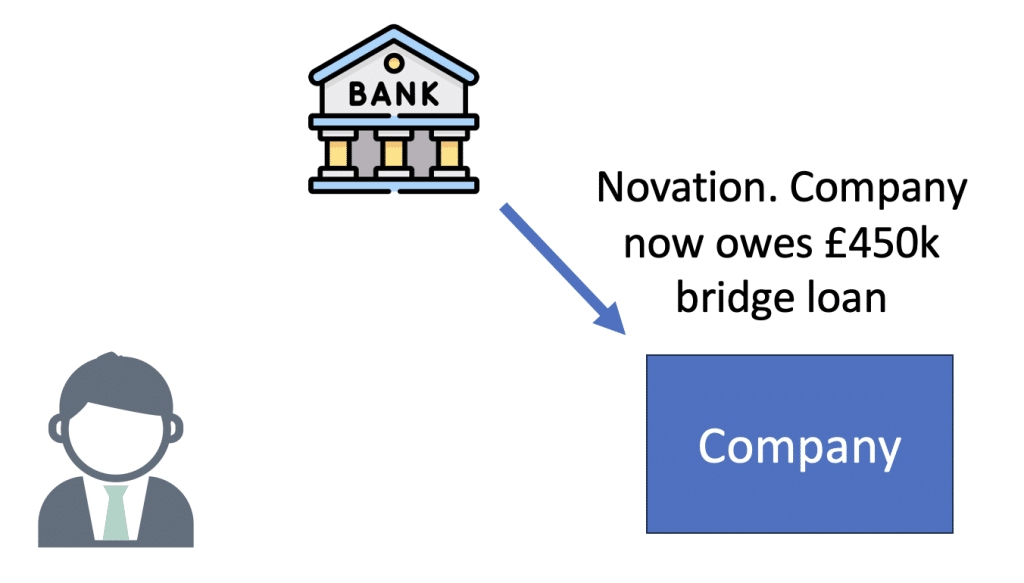

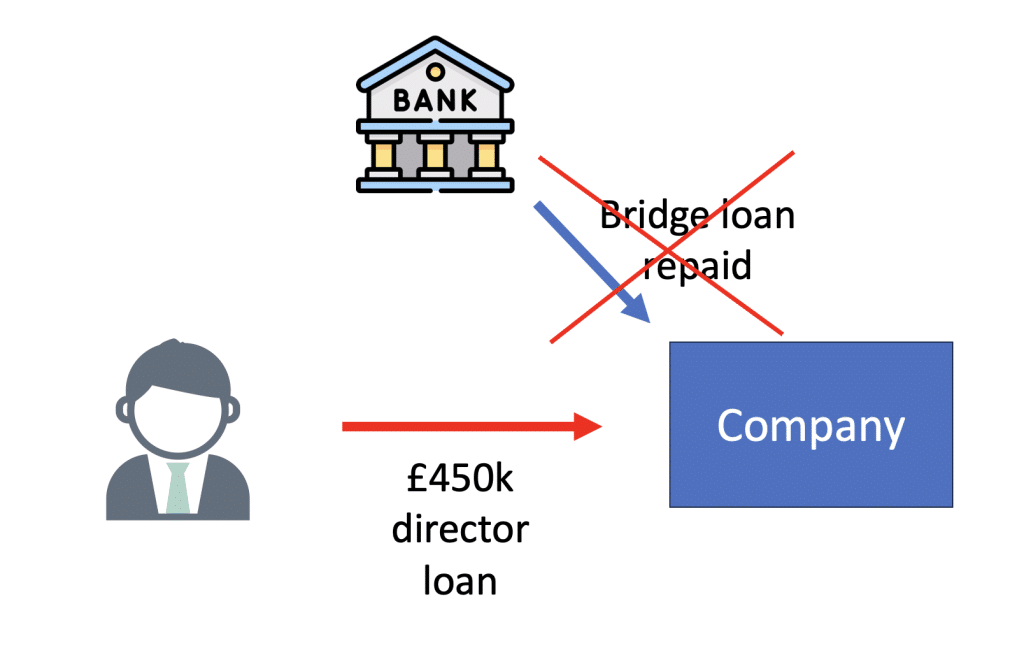

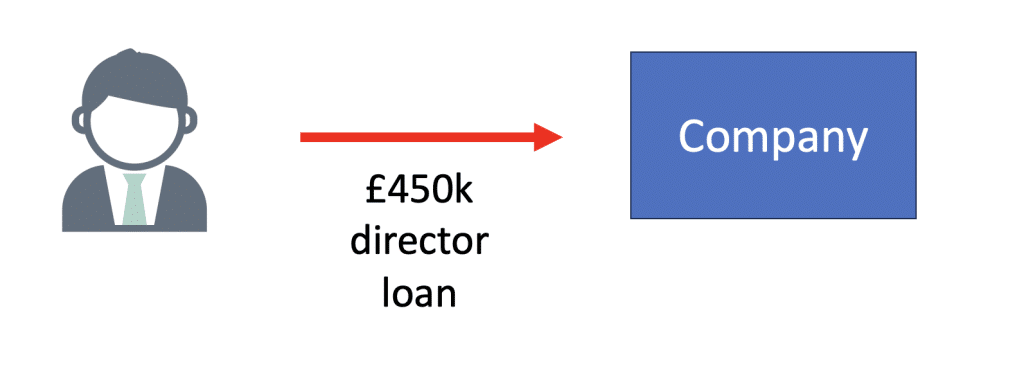

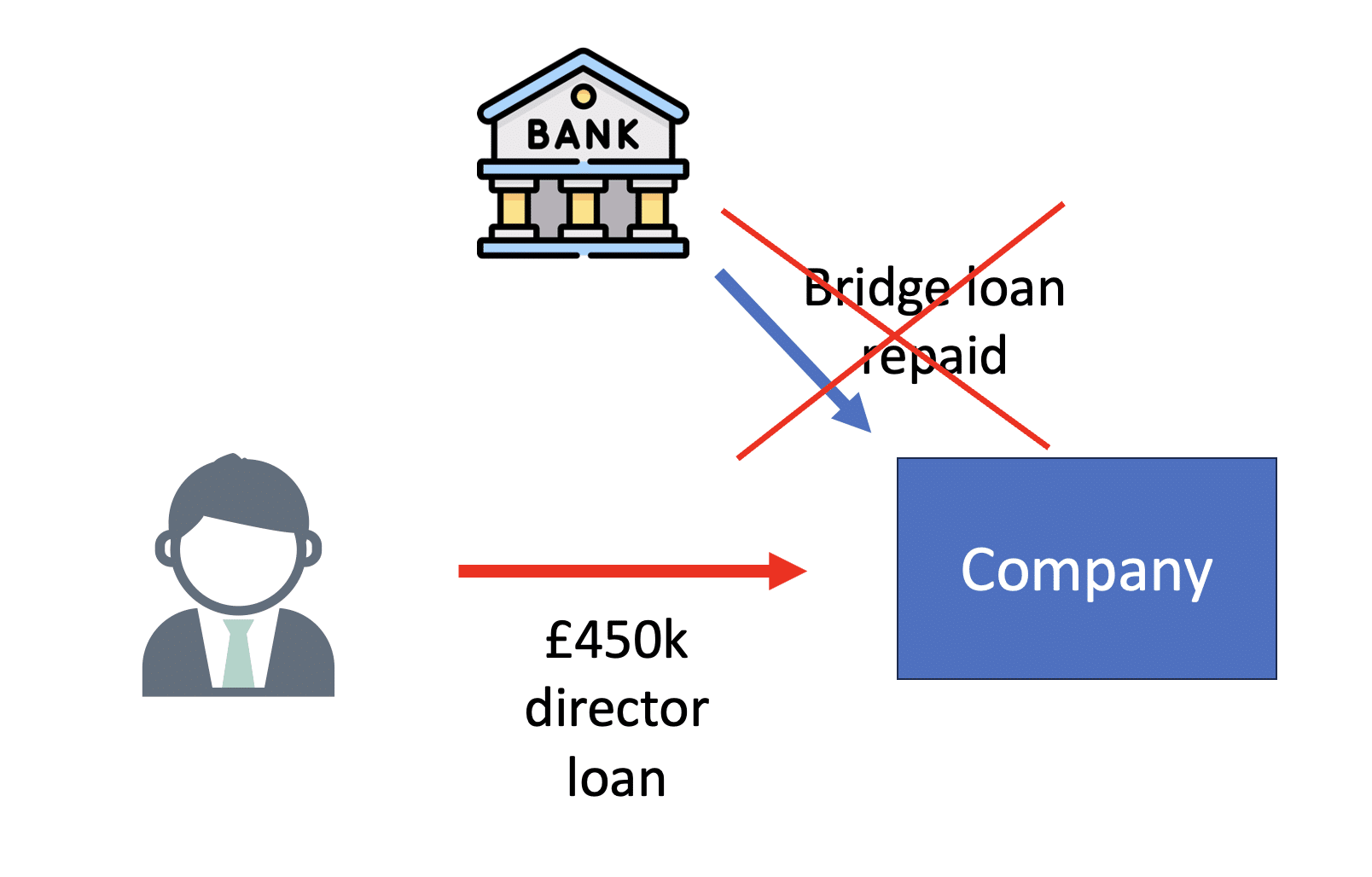

Step 3: Two weeks later, the landlord makes a £450k “director loan” to his company, using the £450k advanced under the bridge loan in step 1 (but the £450k again stays in the solicitor client account – these are just accounting entries):

Step 4: The company immediately uses the £450k to “repay” the bridge loan. “Repay” is in quotes, because the bridge loan money never left the solicitor’s client account:

The outcome of all this:

A £450k “director loan” has been magicked into existence, despite the landlord never having had the £450k, and certainly never having lent any real money to the company. £450k just sat in a solicitor’s client account for two weeks. The only money that really moved was £9,000 – the fees Property118 and the bridge lender received for arranging the structure.

The intended consequences

There are two intended consequences:

- The company now magically owes £450k to the landlord under the “director loan”, despite the landlord never having £450k and the company never receiving £450k. The next £450k of profit made by the company can be paid to the landlord as a repayment of the “loan” – and the landlord won’t be taxed on it. That’s saved/avoided up to £177k of tax.3

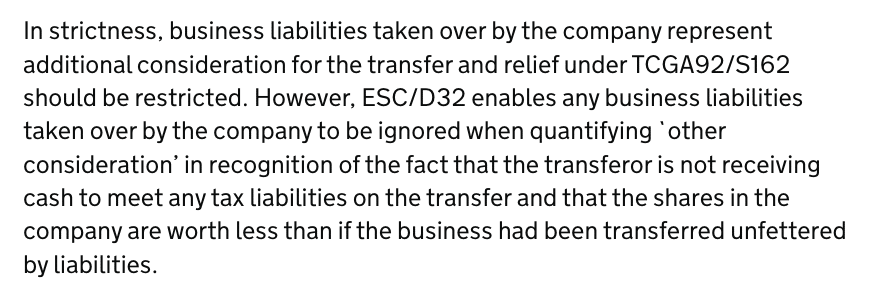

- Incorporation relief applies so there is no capital gains tax because, thanks to the HMRC concession that allows a company can assume liabilities of the business.

The actual consequence – a large CGT hit

When a landlord incorporates their property rental business, an important and legitimate part of the tax planning is ensuring “incorporation relief” applies to prevent an immediate capital gains tax hit on moving the properties into the company.

That requires (amongst other conditions) that the property is sold in consideration for shares in the company, and only for shares.

By concession, HMRC also permit the company to take over business liabilities of the landlord:

In the Property118 scheme, the bridge loan is taken over by the company; but the problem is that it’s not a “business liability” of the landlord. It barely exists at all, and certainly isn’t used for the landlord’s business.

Oh, and HMRC expressly say that this concession can’t be used for tax avoidance:

So incorporation relief isn’t available.

Another consequence – the “director loan” isn’t a loan

This is an artificial tax avoidance structure. The bridge loan is taken immediately prior to incorporation for no purpose other than tax avoidance. Money is then moved in a predetermined circle for no purpose other than tax avoidance, and achieves no result other than tax avoidance. The bridge loan doesn’t even exist for a whole day. Structures of this kind have been repeatedly struck down by the courts over the last 25 years.4

So the question is: despite that artificiality, can the director loan be used to facilitate tax-free profit-extraction in the same way as the “loan note” in the standard version of the structure?

There are several ways this could be viewed:5

- Realistically, the bridge loan did nothing and can be disregarded – but the director loan can still be viewed as part of the consideration for the sale of the property. In other words, if we step back and ignore the silly intermediate steps, the landlord sold the property to the company for consideration comprising: shares, the assumption of the mortgage debt, and another £450k which remains outstanding as a director loan. In this scenario it’s clear CGT incorporation relief fails. But future profits can be paid out on the director loan without suffering income tax. The structure failed to achieve its CGT aim, but did achieve the basic planning aim of the standard structure… in a much more complicated way and at much greater expense for the landlord.

- The bridge loan didn’t exist and neither did the director loan. So future profits can’t be paid out on it, and the structure fails completely. This seems a harsh result. Can HMRC really say the director loan exists enough to kill CGT incorporation relief, but not enough to shield future profits from income tax on dividends? HMRC has a history of running such harsh “double tax” arguments when attacking tax avoidance schemes, but not always successfully.

Failure to disclose to HMRC

Most tax avoidance schemes are required to be disclosed to HMRC under the “DOTAS” rules. The idea is that a promoter who comes up with a scheme has to disclose it to HMRC. HMRC will then give them a “scheme reference number”, which they have to give to clients, and those clients have to put on their tax return. It’s the tax equivalent of putting a “kick me” sign on your back, because the inevitable HMRC response will be to challenge the scheme and pursue the taxpayers for the tax.

For this reason, promoters of tax avoidance schemes typically don’t disclose, even though they should. This is often on the basis of tenuous legal and factual arguments, to which the courts have given short shrift6.

We understand that this structure has not been disclosed under DOTAS. In our view, it clearly should have been. The structure has the main purpose of avoiding tax – indeed that’s its sole purpose. Property118 charge a 1% “arrangement fee” for the director loan structure, which is the kind of “premium fee” that triggers disclosure 7 The failure to disclose means Property118 are liable for penalties of up to £1m.

How do Property118 defend the structure?

In the advice note above, they refer to HMRC guidance in their Business Income Manual. Advisers questioning the structure have received the same explanation. However, that guidance relates to when a company can claim an interest deduction for a loan taken by the company to fund a withdrawal of capital by its shareholders. It has nothing to do with creating a “director loan” out of nothing, and nothing to do with circular tax avoidance transactions.

Property118 have also assured advisers that HMRC have accepted the structure in numerous cases. We are highly doubtful that the true nature of the structure was ever explained to HMRC. Any clearance, or enquiry closure, obtained on the basis of incomplete disclosure is worthless.

These two responses are typical of Property118 and other avoidance scheme promoters. Little or no reference is ever made to the law, and certainly never to tax avoidance caselaw. Instead, HMRC guidance is quoted out of context, and clients are assured that nothing has ever gone wrong in the past.

For what it’s worth, we don’t believe Property118 know what they’re doing is improper (or they presumably wouldn’t publish full details of the scheme). Our explanation is incompetence rather than fraud – nobody at Property118, or Cotswold Barristers, has any tax expertise.

What should happen next?

Property118 are entirely unregulated. The only body who can take action against them is HMRC – which should investigate Property118 for failing to disclose schemes that were disclosable under DOTAS. It may well have been unaware of the scheme before now – the nature of the scheme is such that it may have been completely undisclosed on landlords’ tax returns.

We will be referring Cotswold Barristers to the Bar Standards Board for their role promoting the structure.

The bank providing the bridge loan surely knows what’s going on (anti-money laundering rules require it to). Its involvement may breach the Code of Practice on Taxation for Banks, which generally prohibits banks from facilitating tax avoidance schemes.

No ICAEW-regulated accountant or CIOT/ATT tax adviser should participate in the structure – it breaches the Professional Conduct in Relation to Taxation (PCRT) rules.

No law firm should be facilitating this structure. The Solicitors Regulation Authority prohibits firms from using their client accounts as bank accounts or as pure escrow accounts. The SRA has recently taken enforcement action against firms doing this. Solicitors are also bound by the PCRT rules.

What if you’ve implemented this structure?

We would strongly suggest you seek advice from an independent tax professional, in particular a tax lawyer or an accountant who is a member of a regulated tax body (e.g. ACCA, ATT, CIOT, ICAEW, ICAS or STEP). Given the potential for a mortgage default, we would also suggest you urgently seek advice from a solicitor experienced with trusts and mortgages/real estate finance (e.g. a member of STEP).

We would advise against approaching Property118 given the obvious potential for a conflict of interest.

Thanks to accountants and tax advisers across the country for telling us about their experiences with Property118, as well as the clients who contacted us directly. Particular thanks to Q and to A.

Landlord image by rawpixel.com on Freepik. Bank image by Freepik – Flaticon

Footnotes

Why a loan note and not a loan? Because, conceptually, the company is then giving something (the loan note) as part of the purchase price for the properties. In part because the tax treatment for the company is more certain, as a loan note is clearly a “loan relationship” for tax purposes, and simply leaving money on account may not be ↩︎

As explained in our original report, the transfer of the property is actually effected using a trust rather than a normal legal transfer, to avoid having to obtain the consent of the lender. The mortgage loan isn’t novated, but the company agrees to indemnify the landlord for the payments under the mortgage. The trust causes a number of serious legal and tax complications, not least triggering a mortgage default. However, to keep this example clear, we’ll ignore the trust in this report. ↩︎

The highest marginal rate of tax on dividends is 39.35% ↩︎

We are only aware of one such scheme that wasn’t defeated – SHIPS 2, essentially because the legislation in question was such a mess that the Court of Appeal didn’t feel able to apply a purposive construction. The consequence of that decision was the creation of the GAAR, which doubtless would have kiboshed SHIPS 2 had it existed at the time ↩︎

Our original draft suggested the second scenario was more likely; on reflection we think that would be a harsh result. The CGT element of the structure still fails, but the taxpayer may avoid a double tax disaster ↩︎

See e.g. the Hyrax case, where the tribunal described as “incredible” the evidence of one witness that she wasn’t aware the transaction was involved tax avoidance ↩︎

Although other possible hallmarks are: the standardised tax product hallmark, the employment income hallmark (if there’s a “relevant step”), and/or the financial products hallmark ↩︎

![To: jeevacation@gmail com[eevacation@gmail com]

From: Peter Mandelson

Sem: Sun 11/7/2010 2 34 57 PM

Subyect: Fwd Rio apartment

Seat to mys bank manager Gratetul tor helpful thoughts trom my chief lite adviser

Sent from ims iPad

Bevin torwarded messave

From: Peter Mander iS

Date: 7 November 2010 [4 29 12 GMI

Subject: Rio apartment

P| ag awe dpeecussed Pan consdernne a purchase of an apartmentin Rion Ttisain](https://taxpolicy.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Screenshot-2026-01-31-at-21.27.15-640x360.png)

Leave a Reply